Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is a crucial mediator of breast development, and loss of TGF-β-induced growth arrest is a hallmark of breast cancer. TGF-β has been shown to inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity, which leads to the accumulation of hypophosphorylated pRB. However, unlike other components of TGF-β cytostatic signaling, pRB is thought to be dispensable for mammary development. Using gene-targeted mice carrying subtle missense changes in pRB (Rb1ΔL and Rb1NF), we have discovered that pRB plays a critical role in mammary gland development. In particular, Rb1 mutant female mice have hyperplastic mammary epithelium and defects in nursing due to insensitivity to TGF-β growth inhibition. In contrast with previous studies that highlighted the inhibition of cyclin/CDK activity by TGF-β signaling, our experiments revealed that active transcriptional repression of E2F target genes by pRB downstream of CDKs is also a key component of TGF-β cytostatic signaling. Taken together, our work demonstrates a unique functional connection between pRB and TGF-β in growth control and mammary gland development.

TGF-β is a potent inhibitor of MEC proliferation and plays a key role in mammary gland development (55). Specific loss of its ability to arrest proliferation is an essential step in the development of breast cancer, while its ability to induce other cellular changes is maintained and used to drive oncogenesis (30, 55). However, selective loss of TGF-β growth inhibition responses rarely occur at the level of the TGF-β receptor or Smad proteins, which are common to many aspects of TGF-β signaling (55). Instead, disruption of the TGF-β cytostatic response often occurs at the level of CDK regulation, leaving other protumorigenic aspects of TGF-β signaling intact (56). This underscores the importance of understanding all cell cycle-regulatory targets of TGF-β, as they are candidates for mutation in breast cancer (15).

TGF-β suppresses proliferation by inducing growth arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (54, 55). TGF-β signaling results in transcriptional repression of proproliferative genes, such as c-Myc (65) and CDC25A (38), and, concomitantly, transcriptional induction of the CDK inhibitors p21 (11) and p15 (31), as well as stabilization of the p27 protein (66). This creates a global inhibition of CDK activity that leads to dephosphorylation and activation of pRB in G1 (56). Despite the requirement for pRB in TGF-β-induced cell cycle arrest (34), it is rarely considered a component of this signaling pathway (55). Because pRB controls the final regulatory step before commitment to DNA replication (87), activation of any pathway that results in G1 arrest regulates pRB function, suggesting that pRB uses the same G1 arrest mechanism independently of the initial stimulus that causes it. However, most experiments investigating pRB's growth arrest mechanism have relied on its reexpression in the RB1-deficient Saos-2 cell line as the arrest stimulus (6, 7, 14, 35, 68, 76). The artificial nature of these experiments leaves open the possibility that pRB may have unique activities that are invoked depending on the growth arrest signal.

Mice deficient for TGF-β1, -2, or -3 die as embryos or neonates due to extensive defects in development (42, 45, 67, 74, 79). Strikingly, disruption of TGF-β signaling specifically in the mammary gland causes defects such as hyperplastic ductal epithelium and defective nursing (20, 21, 28, 29, 41). The relative importance of TGF-β growth inhibition compared to its other morphogenic signals in mammary gland development is unclear (22, 77). However, many targets and components of TGF-β's cytostatic signaling cascade, such as cyclin D1 and p27, also participate in controlling mammary epithelial proliferation during development (25, 27, 48, 59, 80, 81). Surprisingly, it has been suggested that pRB may be dispensable for this process (73). Complete loss of pRB function in mice results in embryonic lethality shortly after the formation of the mammary anlagen (8, 40, 49). To study postnatal mammary development, Robinson et al. transplanted Rb1−/− anlagen into clarified fat pads of wild-type females (73). They found no differences in mammary gland development or tumor formation. However, transplant experiments have a number of shortcomings. For example, transplanted anlagen do not form a connection with the nipple, preventing a complete study of mammary gland function. Furthermore, complete loss of pRB results in upregulation of the related protein p107, which can compensate for some aspects of pRB function (37, 71). This highlights our limited knowledge of pRB function in mammary gland development and emphasizes the need for more sophisticated approaches to study its potential role in this tissue.

To exert control over proliferation, pRB interacts with E2F transcription factors and corepressor proteins to block expression of genes that are involved in cell cycle progression (5, 18, 82, 84). Most corepressors contact pRB using an LXCXE peptide motif. This allows pRB-E2F complexes to recruit chromatin-remodeling factors, such as DNA methyltransferases, histone methyltransferases, histone deacetylases, and helicases, to actively repress transcription (4, 17, 46, 53, 61, 72, 83). The binding cleft on pRB that contacts the LXCXE motif is a highly conserved region of the growth-suppressing “pocket” domain (50). This hydrophobic cleft was first identified as the site of contact for LXCXE motifs in viral oncoproteins, such as adenovirus E1A, simian virus 40 large T antigen, and human papillomavirus E7 (12, 19, 58, 85). The fact that so many cellular proteins can use an LXCXE motif to bind to pRB suggests that this cleft serves an important physiological purpose. However, few LXCXE motif-containing proteins are known to be required for pRB-dependent cell cycle arrest (2, 88). Thus, it remains unclear whether LXCXE-dependent interactions are broadly required for pRB action or for a subset of its growth-inhibitory activities.

In an effort to understand the importance of the LXCXE binding cleft in pRB growth arrest during development, we used two knock-in mutant mouse strains termed Rb1ΔL and Rb1NF in which the LXCXE binding site on pRB had been disrupted by mutagenesis (39). Contrary to previous reports, we demonstrate that pRB has a critical role in mammary gland development. Loss of pRB-LXCXE interactions leads to defects in nursing and epithelial growth control. These phenotypes are linked to a disruption in TGF-β growth inhibition in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mammary glands. The inability of TGF-β to block proliferation occurs despite inhibition of CDKs and appears to be dependent on the ability of pRB to actively repress the expression of E2F target genes. This suggests that pRB has a more intimate role in the TGF-β growth arrest pathway, because TGF-β requires LXCXE-dependent interactions where other pRB-dependent arrest mechanisms do not. Furthermore, this study reveals an unappreciated role for pRB in mammary gland development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Abbreviations.

The abbreviations used are BrdU, 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; MEC, mammary epithelial cell; MEF, murine embryonic fibroblast; pRB, retinoblastoma protein; P2, day 2 postparturition; Rb1, retinoblastoma gene; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; ES, embryonic stem; MMTV, mouse mammary tumor virus; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; GST, glutathione S-transferase.

Mouse strains.

The Rb1ΔL mouse strain containing three amino acid substitutions in the Rb1 locus has been previously described (39). Analysis of Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice was performed on a mixed 129/B6 background. To generate the Rb1NF strain, correctly targeted TC1 ES cells were identified by Southern blotting as shown in Fig. 1B and C and injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. Male chimeras were bred to C57/BL6 females, and agouti progeny were bred to 129 Sv/Ev/Tac mice that contained the Cre recombinase gene driven by the protamine promoter (PrmCre) (62). Males that carried Rb1NF(Neo) and PrmCre expressed Cre recombinase during spermatogenesis, which led to excision of the Neo cassette in sperm. These mice were then bred to generate Rb1NF/NF progeny and were subsequently studied in a mixed 129/B6 background. Genotyping methods and primer sequences are available upon request. MMTV TGF-β1223/225 mice express simian TGF-β1 carrying serine mutations at cysteines 223 and 225 of the TGF-β1 precursor, resulting in the production of a constitutively active form of the mature protein (64). These mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories on a C57/B6 background and were bred to the Rb1ΔL mutation, creating a mixed 129/B6 genetic background.

FIG. 1.

Two knock-in mouse strains with disrupted LXCXE interactions. (A) Structural depiction of pRB interacting with the LXCXE motif of human papillomavirus (HPV) E7. Side chains from amino acids 746, 750, and 754 on pRB mediate the interaction with the LXCXE peptide and are colored turquoise. The Rb1ΔL mutation changes these amino acids to alanines (red), removing one side of the LXCXE binding cleft, while the Rb1NF mutation adds a bulky phenylalanine instead of an asparagine at amino acid 750 (red). This is predicted to occupy more space and block access to the LXCXE binding cleft. (B) Genomic structure of Rb1. The targeting vector containing a LoxP-flanked PGK-neo cassette inserted into intron 23 and the mutation N750F in exon 22 are indicated. A new XbaI site was introduced into intron 21. Homologous recombination resulted in the Rb1NF-neo allele. The location of the 5′ probe used for Southern blotting is also shown. Following germ line transmission, the correctly recombined allele was generated by crossing chimeric males to a Cre-expressing transgenic strain. The structure of the Rb1NF allele in which Neo has been correctly excised is shown at the bottom. (C) Southern blot of representative ES clones digested with XbaI and probed with the 5′ probe. (D) The ability of GST-E1A and GST-DP1/His-E2F3 to interact with pRBΔL and pRBNF was tested in GST-pulldown assays, and bound pRB protein was detected by Western blot analysis.

Nursing data were collected from birth (P0) to weaning. Females were considered unable to nurse if all pups died within the first 2 days postparturition and were considered able to partially nurse if some, but not all, pups survived past P2. Both multiparous and uniparous females were used in the study. All animals were housed and handled as approved by the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Histology and mammary whole mounts.

The second and third thoracic mammary glands were dissected at 8 weeks of age or at P2 and fixed in neutral buffered 10% formalin. The fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm-thick sections, and stained with H&E. To determine the extent of hyperplasia, the ductal cross sections present per paraffin section were counted and the fraction of hyperplastic ducts per genotype was calculated. Cross sections from three to nine females per genotype were quantified. Ductal cross sections with more than three layers of epithelial cells were scored as hyperplastic. For whole-mount experiments, the fourth inguinal mammary gland was removed, mounted on a glass slide, and stained with Carmine Red using standard methods.

Detection of cytokeratin 18 and cytokeratin 14 was performed on paraffin sections that had been deparaffinzed and rehydrated using a series of xylene and ethanol washes. The sections were brought to a boil in sodium citrate buffer and then maintained at 95°C for 10 min. The cooled sections were rinsed in water three times for 5 minutes each time and then rinsed in PBS for 5 minutes. The sections were blocked in 2.5% horse serum/2.5% goat serum in PBS-0.3% Triton X for 1 hour. The sections were incubated with anti-cytokeratin 18 (KS18.04; Fitzgerald) and anti-cytokeratin 14 (AF64; Covance) overnight at 4°C and then rinsed in PBS three times for 5 minutes each time. The slides were incubated with horse anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-fluorescein isothiocyanate and goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-Texas Red secondary antibodies (FI-2000 and TI-FI-1000; Vector) for 1.5 h and then rinsed in PBS as described above. The slides were mounted with Vectashield plus DAPI (H-1200; Vector) and sealed with nail polish. Fluorescent images were captured on a Zeiss Axioskop40 microscope and Spot Flex camera and colored using EyeImage software (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Mammary transplants.

Mammary transplants were performed as described by Moorehead et al. (57). All transplants were performed using the fourth inguinal glands. The epithelial portions of 3-week-old Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary glands were removed by harvesting the tissue between the lymph node and nipple. Two- by 2-mm sections of this tissue were placed into the cleared fat pads of Fox Chase SCID mice, and the epithelial tissue from Rb1+/+ females was placed in the contralateral fat pads. SCID females were euthanized at 8 weeks of age, and the fraction of hyperplastic ducts was determined as outlined above.

Cell culture.

Primary MECs were harvested as described by Hojilla et al. (36). Each MEC preparation consisted of the mammary glands of four female mice. Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary glands were minced and dissociated in 2 mg/ml collagenase IV in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-F12 medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin, 60 U/ml nystatin, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin for 2 h at 120 rpm at 37°C. The cells were then washed with PBS supplemented with 5% adult bovine serum and plated onto collagen-coated dishes. MEC cultures were maintained with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-F12 medium supplemented with 1% adult bovine serum, 10 μg/ml insulin, 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 20 U/ml nystatin, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin. Finally, the cultures were passaged and purified using a differential dispase treatment.

Keratinocytes were harvested as described previously (16). P0 to P2 animals were euthanized and immersed in 70% ethanol for 25 min at 4°C to sterilize them. Limbs, tails, and heads were removed before the dermis and epidermis were isolated from the mice, dermis side down, and rinsed in PBS to remove blood. One milliliter of 0.25% trypsin was added to each skin prior to incubating it at 4°C overnight. The skins were placed in 2 ml of fresh trypsin and incubated at 37°C for 30 min to 1 h. The epidermis was then separated from the dermis and minced finely with scissors in 15-ml conical tubes. Fifteen milliliters of keratinocyte growth medium (no-calcium Eagle's minimum essential medium, 8% Chelex-treated fetal bovine serum, 74 ng/ml hydrocortisone, 6.7 ng/ml triiodothyronine, 5 μg/ml insulin, 10−10 M cholera toxin, 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, and 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin) was added to each tube, and the tubes were rocked gently at 37°C for 10 to 15 min. The suspension was filtered through a 70-μm nylon filter and plated at 400,000 cells per well onto collagen- and poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips in 24-well plates. The day after being plated, the cells were rinsed with PBS, and fresh medium was added. The medium was changed every other day to maintain proliferation.

Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL primary MEF cultures were derived as previously described (39). Cell culture experiments were carried out using passage 2 MECs, passage 4 MEFs, and passage 1 keratinocytes.

TGF-β growth arrest assays.

Asynchronously proliferating Rb1+/+, Rb1ΔL/ΔL, and Rb1NF/NF MEFs were treated with 100 pM TGF-β1 (R&D Systems) for 24 h. The cells were then pulse-labeled with BrdU (RPN201V1; Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions for 1.5 h. BrdU incorporation was quantified using flow cytometry as previously described (9). Flow cytometry was carried out on a Beckman-Coulter EPICS XL-MCL instrument. Data analysis was carried out using CXP version 2 software.

Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MECs and keratinocytes were treated with TGF-β1 as outlined above, and BrdU incorporation was measured using immunofluorescence microscopy. The cells were fixed and stained with an antibody against BrdU (1:500) (347580; BD Biosciences) using methodologies outlined by Foster et al. (23). The percentage of BrdU-positive cells was determined from 10 fields of view per treatment group, and the average decrease in proliferation was calculated relative to untreated controls cultured in parallel.

Retroviral infections.

Retroviral infections were performed as previously described (63). BOSC packaging cells were plated at 107 cells per 15-cm dish in 25 to 30 ml of medium 24 h prior to transfection. Each dish was transfected with calcium phosphate with 60 μg of pBabe plasmid containing p16, p21, or vector alone. The BOSC medium was replaced with 10 to 15 ml of fresh medium the next morning. Two days later, the viral supernatant was filtered and supplemented with 4 μg/ml of Polybrene before being placed directly on passage 3 MEFs that had been plated at 8 × 105 cells per 10-cm dish a day earlier. The BOSC cells were given fresh medium, and this was used for a second round of infection 12 h later. After another 12 h of incubation with viral supernatant, the MEFs were given fresh medium for 8 to 12 h, at which point infected MEFs were selected for 4 days with medium containing 5 μg/ml puromycin. After drug selection, the MEFs were replated at low density in drug-containing medium for BrdU labeling and subsequent flow cytometry analysis.

Protein and RNA quantification.

To isolate milk, female mice were injected with 4.5 U oxytocin (Sigma) 4 hours after removal of their offspring. Thirty minutes later, milk was extracted manually. Equal volumes of milk and 2× SDS-PAGE buffer were mixed, denatured, and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue.

To examine the levels of phospho-Smad2 and phospho-pRB, Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs were treated with 100 pM TGF-β1 (R&D Systems) for 2 or 24 h, respectively. Total cellular extracts were isolated in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Equal amounts of total cellular proteins were resolved in each lane by SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and probed using standard methods. Proteins were detected using the following antibodies: Smad2 (sc-6200; Santa Cruz), phospho-Smad2 S465/467 (AB3849; Chemicon), pRB (G3-245; BD-Pharmingen), and phospho-pRB S807/811 (9308; Cell Signaling).

mRNA levels were detected using the Quantigene Plex 2.0 reagent system (Panomics, Freemont, CA) and measured using a BioPlex200 multiplex analysis system according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Luciferase reporter assays.

Luciferase reporter assays were performed as described by Sarker et al. (75). MEFs were seeded at 75,000 cells/well in a six-well plate 24 h prior to transfection. The cells were then cotransfected with 3TP-lux (250 ng/well) (86) and cytomegalovirus-β-galactosidase vector (50 ng/well) using Fugene 6 (Roche) according to the manufacturer's directions. Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β1 (R&D Systems) for 20 h at 37°C. Extracts were prepared using Luciferase assay buffer (Promega), and luciferase activity was measured on a Wallac Victor2 1420 multilabel reader. β-Galactosidase activity was measured colorimetrically using 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside as the substrate. Luciferase activity (measured in relative light units) was normalized to the β-galactosidase measurements.

RESULTS

Two distinct strategies to eliminate pRB-LXCXE interactions.

The LXCXE binding cleft is one of the most highly conserved regions of the retinoblastoma protein (50) and is the contact site for many proteins involved in chromatin regulation (5). However, it is noteworthy that proteins like Suv39h1, Cdh1, and the condensin subunit CAP-D3 do not contain a classic LXCXE motif yet require the LXCXE binding cleft for interaction with pRB (2, 51, 61). To understand the importance of interactions between pRB and cellular partners that use this binding surface, we generated two knock-in mouse models that use distinct mutation strategies to disrupt interactions with this region of pRB. The Rb1ΔLXCXE (referred to here as Rb1ΔL) mutant replaces three well-conserved amino acids (I746, N750, and M754) with alanines and has been previously reported (39) (Fig. 1A). These substitutions are predicted to make the leucine and cysteine residues of the LXCXE motif a loose fit. A different gene-targeting strategy was utilized to block access to the LXCXE binding cleft in the Rb1N750F (Rb1NF) mouse. The Rb1NF mutant substitutes a bulky phenylalanine for asparagine at amino acid 750, which is predicted to sterically block access to the LXCXE binding cleft (Fig. 1A). The targeting strategy used to create this mouse is shown in Fig. 1B, with a representative Southern blot showed targeting by homologous recombination (Fig. 1C). The selectable marker was removed by breeding Cre-transgenic and chimeric mice. F1 offspring were subsequently intercrossed to eliminate the transgene and produce homozygous Rb1NF/NF animals.

Previous cell culture-based studies showed that pRBΔL and pRBNF are unable to bind LXCXE-containing proteins, including adenovirus E1A, human papillomavirus E7, histone deacetylase 1, retinoblastoma binding partner 1, Sin3, and C-terminal binding protein 1, but these pRB mutants retain normal interactions with E2F transcription factors (7, 39). GST pulldown experiments further confirmed that pRBΔL and pRBNF mutant proteins derived from Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF cells are defective for binding to proteins containing a classic LXCXE motif, like E1A (Fig. 1D). In addition, both mutant forms of pRB interact with recombinant E2F3-DP1 equivalently to wild-type pRB. These experiments demonstrate that together the two mouse strains have the necessary properties to define the physiological contexts in which pRB-LXCXE interactions are required, regardless of how the interacting proteins contact this binding site on pRB.

Nursing defects in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF female mice.

Mice homozygous for LXCXE binding cleft mutations are viable and indistinguishable from wild-type littermates; however, mutant females display a distinct defect in mammary gland function. When bred, pups from Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mothers frequently did not survive past P2 (Table 1). Furthermore, many pups that did survive had very small white spots on their abdomens (Fig. 2A), indicating that they were not being nursed regularly.

TABLE 1.

Effects of pRB LXCXE cleft mutations on the ability of female mice to nursea

| ES line | Proportion unable to nurse

|

Proportion partially nursed

|

Proportion nursed completely

|

No. of litters

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rb1+/+ | Rb1ΔL/ΔL | Rb1NF/NF | Rb1+/+ | Rb1ΔL/ΔL | Rb1NF/NF | Rb1+/+ | Rb1ΔL/ΔL | Rb1NF/NF | Rb1+/+ | Rb1ΔL/ΔL | Rb1NF/NF | |

| 27C4 | 0.05 | 0.44d | 0.025 | 0.23 | 0.92 | 0.32 | 40 | 34 | ||||

| 94 | 0 | 0.45b | 0.083 | 0.091 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 12 | 22 | ||||

| Total | 0.038 | 0.44c | 0.038 | 0.17 | 0.92 | 0.37 | 52 | 56 | ||||

| 5F11 | 0.027 | 0.33c | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 37 | 27 | ||||

Mothers were considered unable to nurse if their pups died within the first 2 days post-parturition. Females that lost at least one pup and had at least one pup survive past P2 were considered to have partially nursed. Proportions were compared between relevant groups using a chi-square test.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.005.

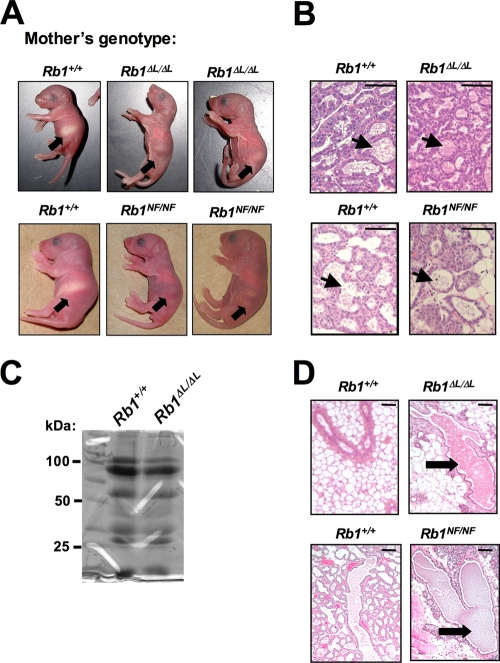

FIG. 2.

Defective nursing in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females. (A) Representative offspring from Rb1+/+, Rb1ΔL/ΔL, and Rb1NF/NF mothers at P2. The arrows indicate the stomachs of the offspring. (B) Paraffin sections of Rb1+/+, Rb1ΔL/ΔL, and Rb1NF/NF mammary glands from postpartum females (P2) were stained with H&E to verify the presence of milk. The arrows indicate milk-filled alveoli. Bars, 50 μm. (C) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining of milk obtained from Rb1+/+and Rb1ΔL/ΔL postpartum females. (D) H&E staining of sections at P2 also indicated dilation of the ducts in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females. The arrows indicate dilated ducts. Scale bars, 200 μm.

In the majority of cases, Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females built nests, and after delivery, offspring were cleaned and present in the nest. The mothers quickly retrieved offspring that we removed from the nests, and pups were routinely observed attempting to suckle. Thus, despite ostensibly normal maternal and offspring behavior, little or no milk was observed in the stomachs of newborns from Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mothers, indicating that impaired milk intake caused the neonatal lethality (Fig. 2A).

To confirm that there were no defects in milk production, we performed histological analysis of postpartum mammary tissue from Rb1+/+, Rb1ΔL/ΔL, and Rb1NF/NF females. All had undergone similar degrees of lobuloalveolar formation, and the alveoli contained milk at P2 (Fig. 2B). SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining of milk obtained from Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary glands revealed no differences in milk protein content between the genotypes, suggesting that neonatal morbidity was not due to poor milk quality from Rb1 mutant mothers (Fig. 2C). However, histological analysis of mammary glands from lactating and multiparous mutant females revealed large, dilated ducts containing milk (Fig. 2D), a phenotype consistent with an inability to secrete milk (43).

These experiments indicate that while Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females are able to produce milk, they have difficulty excreting it from their mammary glands, frequently resulting in neonatal lethality. The prevalence of this nursing defect in mouse lines from two separate ES cell clones of the Rb1ΔL mutant, as well as the Rb1NF/NF mutant, indicates that pRB-LXCXE interactions are critical for mammary gland function. By extension, we conclude that pRB has an essential function in mammary gland development.

Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females develop hyperplasia of the mammary ductal epithelium.

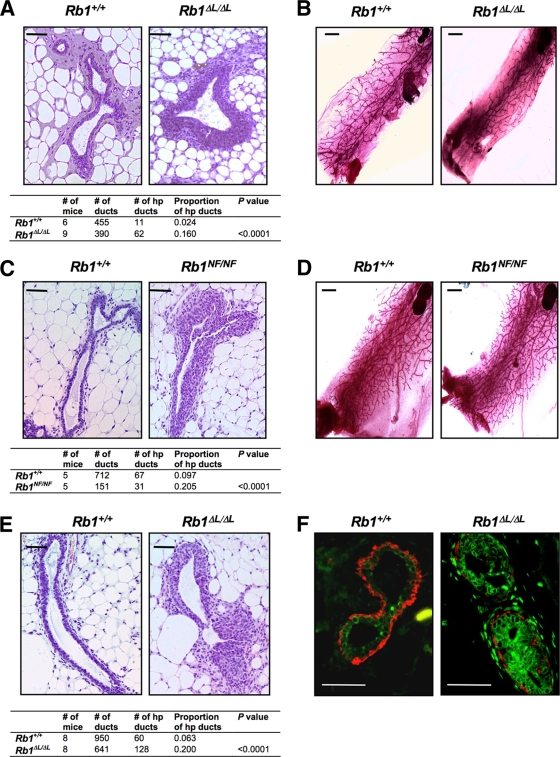

The disruption in milk expulsion exhibited by mutant Rb1 mammary glands prompted us to examine mammary gland development in these mice. Mammary gland histology revealed hyperplastic growth in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mammary glands throughout development (Fig. 3A and C and data not shown). Hyperplasia was characterized by increased luminal epithelial cell layers (Fig. 3F), as well as invagination of the epithelium into the lumen of the duct. The tables in Fig. 3A and C show a significantly elevated frequency of hyperplastic ducts in Rb1 mutant mice compared with controls (P < 0.0001). These data suggest that pRB-LXCXE interactions are required for proliferative control of mammary ductal epithelium during development. Conversely, degrees of ductal infiltration of the fat pad were similar between wild-type and mutant genotypes, as revealed by Carmine Red staining of mammary gland whole mounts (Fig. 3B and D). In addition, branching frequency and overall ductal morphogenesis appeared normal, suggesting that hyperplasia that is visible at a microscopic level throughout development does not manifest in more severe developmental problems.

FIG. 3.

Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females develop hyperplasia of mammary ductal epithelia. (A) H&E staining of Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary tissue sections from 8-week-old mice. Each image displays a representative cross section of ducts used to count epithelial layers. Ducts three or more cells thick were scored as hyperplastic. The accompanying table displays the proportions of hyperplastic (hp) ducts found in wild-type and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary glands. (B) Carmine Red-stained mammary gland whole mounts from 12-week-old mice for the indicated genotypes. (C) An analysis identical to that performed for panel A is shown for Rb1+/+ and Rb1NF/NF mice. (D) Whole-mount analysis was also performed on matched wild-type and Rb1NF/NF mice. (E) Mammary epithelial tissue from Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice was transplanted into clarified fat pads of Fox Chase SCID hosts. Tissue sections from the transplanted mammary glands were stained and analyzed as for panel A. The proportions of hyperplastic ducts for the genotypes were compared using a chi-square test. (F) Paraffin sections from 8-week-old mice were stained for the luminal epithelial and basal/myoepithelial markers cytokeratin 18 (green) and cytokeratin 14 (red). Scale bars: A, C, and E, 200 μm; B and D, 2 mm; F, 50 μm.

Both epithelial and stromal factors influence ductal development. To determine whether disruption of LXCXE interactions within the mammary epithelium was sufficient to enhance ductal growth, we transplanted mammary epithelial tissue from wild-type and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mutants into cleared fat pads of Fox Chase SCID recipients prior to puberty. H&E staining revealed that hyperplastic epithelia were evident in Rb1ΔL/ΔL glands, even in the presence of wild-type stroma and endocrine factors (Fig. 3E). This demonstrates that overproliferation of the mammary ductal epithelium in Rb1 mutant mice is not a secondary consequence of altered endocrine signaling or signaling from the surrounding stroma, but rather is epithelial cell autonomous.

This analysis reveals a striking defect in mammary ductal development in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF virgin mice. This defect is specific to the epithelial compartment, as ductal branching, which relies on stromal signaling (41), is intact, and the transplants revealed that the hyperplasia persists even in the presence of wild-type stroma. Transplantation experiments further demonstrated that the hyperplasia is phenotypically distinct from the apparently normal development that takes place with transplanted Rb1−/− mammary anlagen (73). Consequently, these Rb1 mutant strains have revealed a key role for pRB in mammary epithelial proliferation and function.

Defective TGF-β growth inhibition in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF cells contributes to hyperplasia.

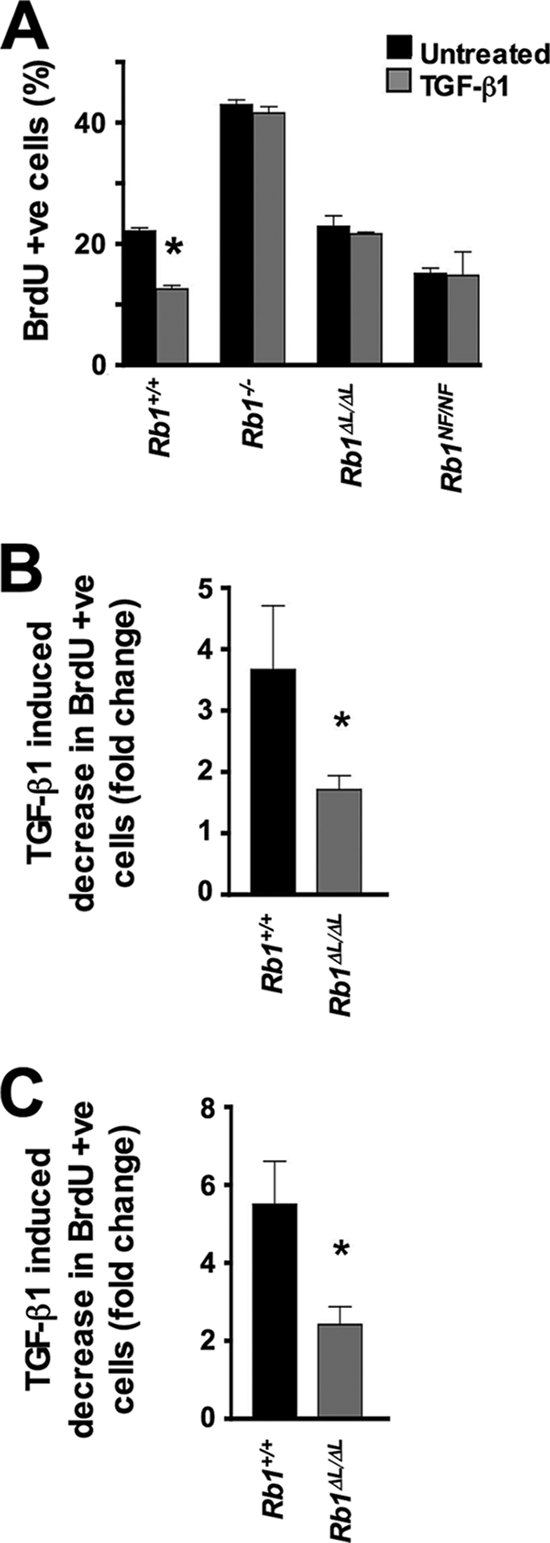

TGF-β is essential for growth control and development of the mammary gland (22, 55). Interestingly, excessive ductal proliferation is seen in mice hemizygous for Tgf-β1 or expressing a dominant-negative TGF-β type II receptor (20, 21, 28, 29, 41). Furthermore, dominant-negative TGF-β type II receptor mice display a nursing defect (29). The similarity of phenotypes between mice defective for pRB-LXCXE interactions and mice defective for TGF-β signaling within the mammary epithelium prompted us to examine the ability of Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF cells to respond to a TGF-β1 growth arrest signal. We treated primary MEFs from Rb1+/+, Rb1ΔL/ΔL, and Rb1NF/NF mice with TGF-β1 for 24 h, pulse-labeled them with BrdU, and then quantified the percentage of cells incorporating BrdU by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A). Rb1−/− cultures served as an important control because they are known to be refractory to TGF-β1 growth arrest (34). In this experiment, Rb1+/+ MEFs showed reduced BrdU incorporation in response to TGF-β1, while Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF fibroblasts were unresponsive, indicating that pRB-LXCXE interactions are necessary for TGF-β-mediated growth arrest.

FIG. 4.

Defective TGF-β growth inhibition in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF cells. (A) Rb1+/+, Rb1−/−, Rb1ΔL/ΔL, and Rb1NF/NF MEFs were treated with TGF-β1 and pulse-labeled with BrdU 24 h later. BrdU incorporation was measured by flow cytometry, and the percent incorporation is shown for each genotype. (B and C) MECs (B) and keratinocytes (C) were treated with TGF-β1 for 24 h and pulse-labeled with BrdU as for panel A. The percentage of cells incorporating BrdU was measured by immunofluorescence microscopy, and the decrease in proliferation between treated and untreated cultures was determined. The average of three independent experiments is shown. The asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (Student's t test; P < 0.05). The error bars indicate 1 standard deviation from the mean. +ve, positive.

This analysis of TGF-β growth control was expanded to include other cell types that are more sensitive to TGF-β-induced cell cycle arrest. We prepared primary MECs and plated them in duplicate, and TGF-β1 was added to one of each pair. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy, and the decrease in incorporation was calculated using the untreated control as a reference (Fig. 4B). We found that the ability to induce TGF-β1 growth arrest was drastically reduced in Rb1ΔL/ΔL MECs. Rb1+/+ MECs had almost a fourfold decrease in cell proliferation, while Rb1ΔL/ΔL MECs showed less than twofold reduction in BrdU incorporation (P = 0.03). We also performed this experiment with Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL primary keratinocytes (Fig. 4C). Rb1+/+ keratinocytes displayed a large decrease in BrdU incorporation, while Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells demonstrated only a 2.4-fold reduction in proliferation (P = 0.0113). From these experiments, we conclude that pRB-LXCXE interactions are critical for TGF-β growth control in multiple cell types.

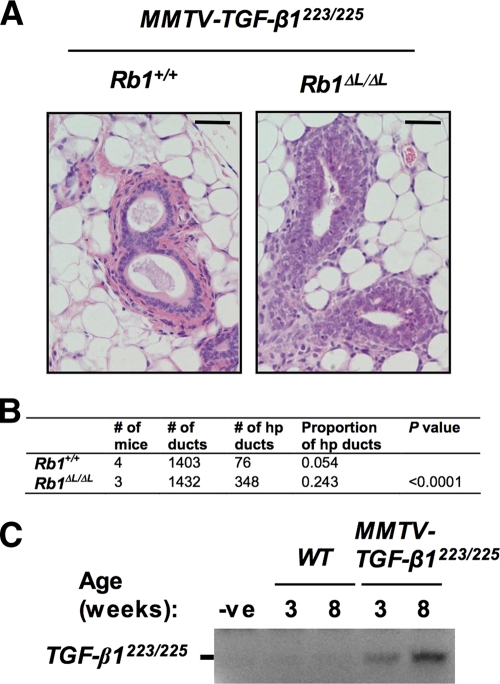

To validate that resistance to TGF-β growth inhibition contributes to the developmental defects seen in the mammary glands of mice lacking LXCXE interactions, we combined the Rb1ΔL mutation with an MMTV TGF-β1 transgene to determine whether hyperplastic ductal growth of Rb1ΔL/ΔL epithelia could be suppressed in the presence of excess TGF-β1. Figure 5 shows our analysis of ductal hyperplasia in 8-week-old Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice overexpressing a constitutively active form of TGF-β1. H&E staining of ductal cross sections showed a persistent hyperplastic phenotype that was indistinguishable from Rb1ΔL/ΔL alone (compare Fig. 5A with Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the frequency of hyperplastic ducts in Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice overexpressing active TGF-β1 was also similar to Rb1ΔL/ΔL alone (compare Fig. 5B with Fig. 3A). We also investigated the expression pattern of the MMTV transgene using RT-PCR to detect the simian TGF-β1 transcript (Fig. 5C). This shows that expression of the transgene is evident as early as 3 weeks of age. Thus, even after 5 weeks of persistent expression of a constitutively active form of TGF-β1, the mammary ductal epithelium still overproliferates. This reveals that resistance to TGF-β growth inhibition is an important component of the ductal hyperplasia phenotype.

FIG. 5.

Mammary ductal hyperplasia is caused by defective TGF-β growth inhibition in Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice. Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice were crossed into the MMTV TGF-β1223/225 background. (A) H&E staining of paraffin sections from mammary glands isolated from 8-week-old mice. Cross sections of individual ducts are shown. Ducts that contained three or more epithelial layers were scored as hyperplastic. Scale bars, 200 μm. (B) The proportions of hyperplastic (hp) ducts in MMTV TGF-β1223/225 Rb1+/+ and MMTV TGF-β1223/225 Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary glands were determined and compared using a chi-square test. (C) Reverse transcriptase PCR was used to detect the constitutively active, simian-derived TGF-β1 transcript expressed by the MMTV promoter in MMTV TGF-β1223/225 Rb1ΔL/ΔL mammary glands. WT, wild type; -ve, negative.

These data link the hyperplastic phenotypes observed in mammary epithelium in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mice with an inability to respond to TGF-β growth inhibition. In addition, a small increase in BrdU-positive basal keratinocytes has been observed in Rb1ΔL/ΔL mice compared to controls (1), suggesting that defective TGF-β growth arrest in Rb1ΔL/ΔL keratinocytes may have a mild effect on the epidermis. Our experiments have identified a previously unappreciated role for pRB in mediating TGF-β growth control in mammary epithelium that is necessary for mammary development and function.

Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells transduce TGF-β1-dependent signals.

We next wanted to address the mechanism by which mutations in the LXCXE binding cleft of Rb1 disrupt TGF-β growth inhibition. TGF-β stimulates its receptors to phosphorylate Smad proteins, which translocate to the nucleus and, along with coregulators, activate or repress gene transcription of a number of diverse genes. The targets for activation include plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (10, 13) and the CDK inhibitors p15 and p21 (11, 70). To determine where pRB-LXCXE interactions are required in TGF-β-mediated growth arrest, we analyzed the TGF-β signaling pathway in Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs. Phospho-specific Western blots showed that TGF-β1 treatment of Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs resulted in phosphorylation of Smad2 (Fig. 6A). This suggests that TGF-β receptor expression and function are not significantly altered in Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells.

FIG. 6.

TGF-β1 signaling in Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells does not repress E2F target genes. (A) Phospho-Smad2 levels were measured in TGF-β1-treated Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs by Western blot analysis. (B) Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs were transfected with the 3TP-luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase plasmids. The MEFs were then treated with TGF-β1 for 20 h. The luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase expression and is shown in arbitrary units. (C) Total pRB expression levels, as well as phospho-pRB levels, were measured in TGF-β1-treated Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs by Western blot analysis. (D and E) Rb1+/+, Rb1−/−, and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs were infected with retroviruses expressing either p16 (D) or p21 (E). Following drug selection, the cells were pulse-labeled with BrdU. BrdU incorporation was measured by flow cytometry, and the percent incorporation is shown. (F) The change in mRNA levels in response to TGF-β1 treatment is shown for E2F-responsive genes, as well as the non-E2F-responsive control, ArppP0 (acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 gene). The error bars indicate 1 standard deviation from the mean. The asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (Student's t test; P < 0.05).

To examine Smad-dependent transcription, we utilized the 3TP-lux reporter, which contains TGF-β-responsive elements from the promoter of the plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene driving the expression of firefly luciferase (86). Transfected Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs had comparable levels of luciferase activity when stimulated with TGF-β1 (Fig. 6B). Importantly, luciferase expression was increased to the same extent when Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells were treated with TGF-β1. Together with the phospho-specific Western blot analysis, the luciferase assay data indicate that Smad-dependent signal transduction functions normally in Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells. From these experiments, it is clear that the Rb1ΔL mutation disrupts growth control but does not cause pleiotropic defects in TGF-β signaling.

Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells are unable to repress E2F target genes in response to TGF-β.

Growth inhibition by TGF-β is thought to be the result of multiple, overlapping means of inhibiting CDK activity (54, 55). In G1, this leads to the accumulation of hypophosphorylated pRB and cell cycle arrest (24, 26, 47). To investigate this aspect of TGF-β growth inhibition, we performed phospho-specific Western blot analysis of MEFs treated with TGF-β1. Rb1+/+ and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs had comparable levels of dephosphorylated pRB when treated with TGF-β1 (Fig. 6C), yet Rb1ΔL/ΔL cell proliferation was not reduced under these conditions (Fig. 4A). This indicates that mutant pRB is activated by TGF-β1 signaling and suggests that the defect in growth inhibition is downstream of CDK regulation.

To further confirm that Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells are unable to arrest despite the inhibition of cyclin/CDK activity, we sought to inhibit CDK activity directly. Hypophosphorylation of pRB and G1 arrest can be induced by ectopic expression of INK4 and CIP/KIP family proteins, and this arrest is known to be lost in cells deficient for pRB (44, 52, 60, 78). We used retroviral infection to express either p16 or p21 in Rb1+/+, Rb1−/−, and Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs to study the effects of representative members of the INK4 or CIP/KIP protein families on cell cycle arrest. Rb1+/+ cells had decreased BrdU incorporation after infection with either p16- or p21-expressing viruses, while Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs behaved like Rb1−/− MEFs, with no reduction in BrdU incorporation (Fig. 6D and E). Thus, even when inhibitor expression blocked CDK activity, Rb1ΔL/ΔL MEFs were unable to arrest growth. Based on this analysis, we conclude that TGF-β growth arrest requires a unique aspect of pRB function beyond becoming dephosphorylated and binding to E2Fs.

To understand the nature of the pRB-LXCXE-dependent function that is required for TGF-β-induced growth arrest, we determined whether mutant pRB still represses transcription of E2F target genes. We measured the mRNA levels of five E2F-responsive genes under conditions where TGF-β1 stimulation inhibits proliferation of Rb1+/+ MEFs. While the levels of Pcna (proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene), Ccne1 (cyclin E1 gene), Rbl1 (retinoblastoma-like gene 1 [p107])), Ccna2 (cyclin A2 gene), and Tyms (thymidylate synthase gene) decreased in wild-type TGF-β1-treated cells, there was little change in transcript levels for a number of these genes in Rb1ΔL/ΔL cells (Fig. 6F). In some cases, expression appeared to increase slightly. Given that both wild-type and mutant pRB become hypophosphorylated under these TGF-β1 treatment conditions (Fig. 6C), we interpret this to mean that mutant pRB is active but unable to repress transcription.

This indicates that pRB functions as part of an active repressor complex in TGF-β growth inhibition. Presumably, this complex contains pRB, an LXCXE motif-containing corepressor, and an E2F transcription factor. Since the most obvious defect in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mice lies in proliferative control during mammary gland development, this reveals a novel requirement for pRB-LXCXE interactions in the TGF-β cytostatic response that is uniquely important for mammary gland development and function.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed a number of unexpected findings about TGF-β signaling and pRB in regulating cell proliferation. First, our work highlights a previously unrecognized role for pRB in mammary gland development. Additionally, mutation of the highly conserved LXCXE binding region of pRB creates a very discrete functional defect in the mammary glands of otherwise normal mice. Because TGF-β signaling underlies the mammary gland defects in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mice, our work argues that pRB-LXCXE interactions have a unique functional role in TGF-β-induced growth inhibition.

Our work appears to contradict the report by Robinson, et al. that showed that complete ablation of pRB in transplanted epithelium results in normal mammary gland development (73). However, these apparently paradoxical results may be explained by differences in experimental approaches. First, we discovered hyperplasia in early development of virgin animals, a defect that we were unable to detect in densely packed lactating mammary glands. Since these authors examined only the structure of lactating Rb1−/− mammary glands, it is perhaps not surprising that they did not detect hyperplastic growth. Similar to Robinson, et al., we investigated the density and morphology of alveoli between genotypes in lactating females and did not detect differences. The inability of transplanted mammary glands to form a functional connection with the nipple precluded further assessment of a phenotype in Rb1 null glands. However, our intact-mouse models clearly showed a defect in expelling milk, indicating that fully functional pRB is necessary for lactation. To ascertain the importance of pRB in TGF-β proliferative control, Robinson et al. transplanted WAP-TGF-β1 Rb1−/− epithelium into wild-type recipients. These mice expressed TGF-β1 in alveolar cells during pregnancy and lactation. Again, these alveoli were indistinguishable from wild-type controls. In contrast, the MMTV TGF-β1 transgene used in our experiments revealed in vivo resistance to TGF-β1-induced growth arrest during early development. The challenges presented by transplanting embryonic Rb1−/− anlagen limit the range of developmental events that can be investigated and likely explain why pRB's role in mammary gland development and function has gone unnoticed until now.

Most breast cancers originate from ductal epithelium, and nearly all cell lines derived from breast cancer patients are unresponsive to the growth-inhibiting effects of TGF-β1 in culture (15, 55). Similar to the transplant experiments of Robinson et al., we have not detected spontaneous mammary tumors in Rb1ΔL/ΔL or Rb1NF/NF mice (73). However, it is noteworthy that transgenic mice expressing dominant-negative TGF-β type II receptors have similar defects in their mammary glands and either did not develop spontaneous tumors (3) or developed tumors only after a very long latency (28). Future studies using transgenic induction of mammary tumorigenesis in our Rb1 mutant mice will allow TGF-β's cell cycle control function in cancer development and metastasis to be studied in isolation.

Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF cells are largely refractory to TGF-β1 growth inhibition in cell culture, and our genetic cross to MMTV TGF-β1 mice suggests that loss of this proliferative control mechanism results in hyperplasia. We speculate that TGF-β signaling defects also lead to the nursing defect in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF females, given that mice expressing a dominant-negative TGF-β type II receptor are also reported to have nursing defects (29). We envision a number of scenarios that could explain this defect. One possibility is that overproliferation of the ductal epithelium causes physical blockage of the lumen, preventing milk letdown and ultimately leading to dilated ducts. Another possibility is that the nursing defect is not proliferation related. Since TGF-β signaling is necessary for contraction of smooth muscle cells (32, 33, 69), the distended milk-filled ducts could result from reduced tension in myoepithelial cells. We did observe some ducts that lacked a complete ring of basal/myoepithelial cells in Rb1ΔL/ΔL sections (Fig. 3F), suggesting that there may be disruption of the myoepithelial layer. Therefore, it is possible that TGF-β confers a more contractile phenotype on the myoepithelium during lactation and this is lost in Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF mammary glands.

We have demonstrated that pRB has a much more intimate role in TGF-β-mediated growth arrest than previously anticipated. This interpretation is based on the fact that TGF-β-regulated growth control requires LXCXE interactions. Since Rb1−/− mice are not viable and exhibit numerous proliferative control defects (8, 40, 49) that are complemented in viable Rb1ΔL/ΔL and Rb1NF/NF animals, this indicates that pRB-LXCXE interactions are uniquely needed for TGF-β cell cycle arrest in a very specific tissue. We interpret defective repression of E2F-responsive genes to be the cause of the TGF-β arrest defect because pRB is hypophosphorylated after TGF-β stimulation but transcript levels of E2F targets remain elevated as the cell cycle continues to advance. The identity of the exact LXCXE-interacting protein(s) that pRB needs to contact in this growth arrest paradigm is unclear, as numerous binding partners have been implicated in chromatin regulation during transcriptional repression (4, 17, 46, 53, 61, 72, 83). Identifying and characterizing the corepressor(s) that cooperate with pRB in response to TGF-β will be critical to fully understanding how TGF-β inhibits cell proliferation.

We have demonstrated that pRB has an essential role in growth control of the mammary gland during development. This study also revealed that pRB is a key component of TGF-β-induced growth arrest because it functions differently in this growth arrest pathway than other pRB-dependent growth-suppressing functions in development. The Rb1ΔL and Rb1NF mouse strains will be ideal to further advance our understanding of the mechanism of TGF-β growth arrest in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank numerous colleagues for advice during the course of this research. The 3TP-lux plasmid was the kind gift of Shirin Bonni (University of Calgary). We are grateful for technical assistance from the CHRI histology and LHSC flow cytometry core facilities.

C.E.I., C.H.C., and S.M.F. have all been members of the CIHR-Strategic Training Program in Cancer Research and Technology Transfer. C.H.C. is the recipient of NSERC-CGS and OGS scholarships. S.M.F. acknowledges fellowship support from CBCF Ontario, as well as past support from OGSST. F.A.D. is a Research Scientist of the NCIC/CCS. This work was supported by operating grants from the NIH (CA058320) to J.Y.J.W. and from the Cancer Research Society and CIHR (MOP-64253) to F.A.D.

We declare that we have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 June 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balsitis, S., F. Dick, D. Lee, L. Farrell, R. K. Hyde, A. E. Griep, N. Dyson, and P. F. Lambert. 2005. Examination of the pRb-dependent and pRb-independent functions of E7 in vivo. J. Virol. 7911392-11402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binne, U. K., M. K. Classon, F. A. Dick, W. Wei, M. Rape, W. G. Kaelin, Jr., A. M. Naar, and N. J. Dyson. 2007. Retinoblastoma protein and anaphase-promoting complex physically interact and functionally cooperate during cell-cycle exit. Nat. Cell Biol. 9225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottinger, E. P., J. L. Jakubczak, D. C. Haines, K. Bagnall, and L. M. Wakefield. 1997. Transgenic mice overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor beta receptor show enhanced tumorigenesis in the mammary gland and lung in response to the carcinogen 7,12-dimethylbenz-[a]-anthracene. Cancer Res. 575564-5570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brehm, A., E. A. Miska, D. J. McCance, J. L. Reid, A. J. Bannister, and T. Kouzarides. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature 391597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkhart, D. L., and J. Sage. 2008. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8671-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, H. M., L. Smith, and N. B. La Thangue. 2001. Role of LXCXE motif-dependent interactions in the activity of the retinoblastoma protein. Oncogene 206152-6163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, T. T., and J. Y. J. Wang. 2000. Establishment of irreversible growth arrest in myogenic differentiation requires the RB LXCXE-binding function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 205571-5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke, A., E. Maandag, M. van Roon, N. van der Lugt, M. van der Valk, M. Hooper, A. Berns, and H. te Riele. 1992. Requirement for a functional Rb-1 gene in murine development. Nature 359328-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Classon, M., S. R. Salama, C. Gorka, R. Mulloy, P. Braun, and E. E. Harlow. 2000. Combinatorial roles for pRB, p107 and p130 in E2F-mediated cell cycle control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9710820-10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Datta, P. K., M. C. Blake, and H. L. Moses. 2000. Regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression by transforming growth factor-beta-induced physical and functional interactions between smads and Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 27540014-40019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datto, M. B., Y. Li, J. F. Panus, D. J. Howe, Y. Xiong, and X. F. Wang. 1995. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 925545-5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeCaprio, J. A., J. W. Ludlow, J. Figge, J. Y. Shew, C. M. Huang, W. H. Lee, E. Marsilio, E. Paucha, and D. M. Livingston. 1988. SV40 large tumor antigen forms a specific complex with the product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene. Cell 54275-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennler, S., S. Itoh, D. Vivien, P. ten Dijke, S. Huet, and J. M. Gauthier. 1998. Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J. 173091-3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dick, F. A., E. Sailhamer, and N. J. Dyson. 2000. Mutagenesis of the pRB pocket domain reveals that cell cycle arrest functions are separable from binding to viral oncoproteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 203715-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan, J., and J. Slingerland. 2000. Transforming growth factor-beta and breast cancer, Cell cycle arrest by transforming growth factor-beta and its disruption in cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2116-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Souza, S. J., A. Pajak, K. Balazsi, and L. Dagnino. 2001. Ca2+ and BMP-6 signaling regulate E2F during epidermal keratinocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 27623531-23538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunaief, J. L., B. E. Strober, S. Guha, P. A. Khavari, K. Alin, J. Luban, M. Begemann, G. R. Crabtree, and S. P. Goff. 1994. The retinoblastoma protein and BRG1 form a complex and cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest. Cell 79119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyson, N. 1998. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 122245-2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyson, N., P. Guida, K. Munger, and E. Harlow. 1992. Homologous sequences in adenovirus E1A and human papillomavirus E7 proteins mediate interaction with the same set of cellular proteins. J. Virol. 666893-6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ewan, K. B., H. A. Oketch-Rabah, S. A. Ravani, G. Shyamala, H. L. Moses, and M. H. Barcellos-Hoff. 2005. Proliferation of estrogen receptor-alpha-positive mammary epithelial cells is restrained by transforming growth factor-beta1 in adult mice. Am. J. Pathol. 167409-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewan, K. B., G. Shyamala, S. A. Ravani, Y. Tang, R. Akhurst, L. Wakefield, and M. H. Barcellos-Hoff. 2002. Latent transforming growth factor-beta activation in mammary gland: regulation by ovarian hormones affects ductal and alveolar proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 1602081-2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleisch, M. C., C. A. Maxwell, and M. H. Barcellos-Hoff. 2006. The pleiotropic roles of transforming growth factor beta in homeostasis and carcinogenesis of endocrine organs. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 13379-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster, R. F., J. M. Thompson, and S. J. Kaufman. 1987. A laminin substrate promotes myogenesis in rat skeletal muscle cultures: analysis of replication and development using antidesmin and anti-BrdUrd monoclonal antibodies. Dev. Biol. 12211-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furukawa, Y., S. Uenoyama, M. Ohta, A. Tsunoda, J. D. Griffin, and M. Saito. 1992. Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product in human monocytic leukemia cell line JOSK-I. J. Biol. Chem. 26717121-17127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gadd, M., C. Pisc, J. Branda, V. Ionescu-Tiba, Z. Nikolic, C. Yang, T. Wang, G. M. Shackleford, R. D. Cardiff, and E. V. Schmidt. 2001. Regulation of cyclin D1 and p16(INK4A) is critical for growth arrest during mammary involution. Cancer Res. 618811-8819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geng, Y., and R. A. Weinberg. 1993. Transforming growth factor β effects on expression of G1 cyclins and cyclin-dependent protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9010315-10319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng, Y., Q. Yu, E. Sicinska, M. Das, R. T. Bronson, and P. Sicinski. 2001. Deletion of the p27Kip1 gene restores normal development in cyclin D1-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98194-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorska, A. E., R. A. Jensen, Y. Shyr, M. E. Aakre, N. A. Bhowmick, and H. L. Moses. 2003. Transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor exhibit impaired mammary development and enhanced mammary tumor formation. Am. J. Pathol. 1631539-1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorska, A. E., H. Joseph, R. Derynck, H. L. Moses, and R. Serra. 1998. Dominant-negative interference of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor in mammary gland epithelium results in alveolar hyperplasia and differentiation in virgin mice. Cell Growth Differ. 9229-238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanahan, D., and R. A. Weinberg. 2000. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 10057-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannon, G. J., and D. Beach. 1994. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-beta-induced cell cycle arrest. Nature 371257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hao, H., P. Ropraz, V. Verin, E. Camenzind, A. Geinoz, M. S. Pepper, G. Gabbiani, and M. L. Bochaton-Piallat. 2002. Heterogeneity of smooth muscle cell populations cultured from pig coronary artery. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 221093-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hautmann, M. B., C. S. Madsen, and G. K. Owens. 1997. A transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) control element drives TGFβ-induced stimulation of smooth muscle alpha-actin gene expression in concert with two CArG elements. J. Biol. Chem. 27210948-10956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrera, R. E., T. P. Makela, and R. A. Weinberg. 1996. TGFβ-induced growth inhibition in primary fibroblasts requires the retinoblastoma protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 71335-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinds, P. W., S. Mittnacht, V. Dulic, A. Arnold, S. I. Reed, and R. A. Weinberg. 1992. Regulation of retinoblastoma protein functions by ectopic expression of human cyclins. Cell 70993-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hojilla, C. V., I. Kim, Z. Kassiri, J. E. Fata, H. Fang, and R. Khokha. 2007. Metalloproteinase axes increase beta-catenin signaling in primary mouse mammary epithelial cells lacking TIMP3. J. Cell Sci. 1201050-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurford, R., D. Cobrinik, M.-H. Lee, and N. Dyson. 1997. pRB and p107/p130 are required for the regulated expression of different sets of E2F responsive genes. Genes Dev. 111447-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iavarone, A., and J. Massague. 1997. Repression of the CDK activator Cdc25A and cell-cycle arrest by cytokine TGF-beta in cells lacking the CDK inhibitor p15. Nature 387417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isaac, C. E., S. M. Francis, A. L. Martens, L. M. Julian, L. A. Seifried, N. Erdmann, U. K. Binne, L. Harrington, P. Sicinski, N. G. Berube, N. J. Dyson, and F. A. Dick. 2006. The retinoblastoma protein regulates pericentric heterochromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 263659-3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacks, T., A. Fazeli, E. Schmitt, R. Bronson, M. Goodell, and R. Weinberg. 1992. Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature 359295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joseph, H., A. E. Gorska, P. Sohn, H. L. Moses, and R. Serra. 1999. Overexpression of a kinase-deficient transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor in mouse mammary stroma results in increased epithelial branching. Mol. Biol. Cell 101221-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaartinen, V., J. W. Voncken, C. Shuler, D. Warburton, D. Bu, N. Heisterkamp, and J. Groffen. 1995. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat. Genet. 11415-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi, T., H. M. Kronenberg, and J. Foley. 2005. Reduced expression of the PTH/PTHrP receptor during development of the mammary gland influences the function of the nipple during lactation. Dev. Dyn. 233794-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koh, J., G. H. Enders, B. D. Dynlacht, and E. Harlow. 1995. Tumor-derived p16 alleles encoding proteins defective in cell cycle inhibition. Nature 375506-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulkarni, A. B., C. G. Huh, D. Becker, A. Geiser, M. Lyght, K. C. Flanders, A. B. Roberts, M. B. Sporn, J. M. Ward, and S. Karlsson. 1993. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90770-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lai, A., B. K. Kennedy, D. A. Barbie, N. R. Bertos, X. J. Yang, M. C. Theberge, S. C. Tsai, E. Seto, Y. Zhang, A. Kuzmichev, W. S. Lane, D. Reinberg, E. Harlow, and P. E. Branton. 2001. RBP1 recruits the mSIN3-histone deacetylase complex to the pocket of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor family proteins found in limited discrete regions of the nucleus at growth arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 212918-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laiho, M., J. A. DeCaprio, J. W. Ludlow, D. M. Livingston, and J. Massague. 1990. Growth inhibition by TGF-beta linked to suppression of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Cell 62175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landis, M. W., B. S. Pawlyk, T. Li, P. Sicinski, and P. W. Hinds. 2006. Cyclin D1-dependent kinase activity in murine development and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 913-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee, E. Y., C. Y. Chang, N. Hu, Y. C. Wang, C. C. Lai, K. Herrup, W. H. Lee, and A. Bradley. 1992. Mice deficient for Rb are nonviable and show defects in neurogenesis and haematopoiesis. Nature 359288-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee, J.-O., A. A. Russo, and N. P. Pavletich. 1998. Structure of the retinoblastoma tumour-suppressor pocket domain bound to a peptide from HPV E7. Nature 391859-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Longworth, M. S., A. Herr, J. Y. Ji, and N. J. Dyson. 2008. RBF1 promotes chromatin condensation through a conserved interaction with the Condensin II protein dCAP-D3. Genes Dev. 221011-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lukas, J., D. Parry, L. Aagarrd, D. J. Mann, J. Bartkova, M. Strauss, G. Peters, and J. Bartek. 1995. Retinoblastoma-protein-dependent inhibition by the tumor-suppressor p16. Nature 375503-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Magnaghi, L., R. Groisman, I. Naguibneva, P. Robin, S. Lorain, J. P. Le Villain, F. Troalen, D. Trouche, and A. Harel-Bellan. 1998. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature 391601-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Massague, J. 2000. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Massague, J. 2008. TGFβ in cancer. Cell 134215-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Massague, J., and R. R. Gomis. 2006. The logic of TGFβ signaling. FEBS Lett. 5802811-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moorehead, R. A., C. V. Hojilla, I. De Belle, G. A. Wood, J. E. Fata, E. D. Adamson, K. L. Watson, D. R. Edwards, and R. Khokha. 2003. Insulin-like growth factor-II regulates PTEN expression in the mammary gland. J. Biol. Chem. 27850422-50427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munger, K., B. A. Werness, N. Dyson, W. C. Phelps, E. Harlow, and P. M. Howley. 1989. Complex formation of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product. EMBO J. 84099-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muraoka, R. S., A. E. Lenferink, J. Simpson, D. M. Brantley, L. R. Roebuck, F. M. Yakes, and C. L. Arteaga. 2001. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) is required for mouse mammary gland morphogenesis and function. J. Cell Biol. 153917-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niculescu, A. B., III, X. Chen, M. Smeets, L. Hengst, C. Prives, and S. I. Reed. 1998. Effects of p21 Cip1/Waf1 at both the G1/S and the G2/M cell cycle transitions: pRb is a critical determinant in blocking DNA replication and in preventing endoreduplication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18629-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nielsen, S. J., R. Schneider, U. M. Bauer, A. J. Bannister, A. Morrison, D. O'Carroll, R. Firestein, M. Cleary, T. Jenuwein, R. E. Herrera, and T. Kouzarides. 2001. Rb targets histone H3 methylation and HP1 to promoters. Nature 412561-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Gorman, S., N. A. Dagenais, M. Qian, and Y. Marchuk. 1997. Protamine-Cre recombinase transgenes efficiently recombine target sequences in the male germ line of mice, but not in embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9414602-14607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pear, W. S., G. P. Nolan, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. Production of high-titre helper-free retroviuses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 908392-8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pierce, D. F., Jr., M. D. Johnson, Y. Matsui, S. D. Robinson, L. I. Gold, A. F. Purchio, C. W. Daniel, B. L. Hogan, and H. L. Moses. 1993. Inhibition of mammary duct development but not alveolar outgrowth during pregnancy in transgenic mice expressing active TGF-beta 1. Genes Dev. 72308-2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pietenpol, J. A., J. T. Holt, R. W. Stein, and H. L. Moses. 1990. Transforming growth factor beta 1 suppression of c-myc gene transcription: role in inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 873758-3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Polyak, K., J. Y. Kato, M. J. Solomon, C. J. Sherr, J. Massague, J. M. Roberts, and A. Koff. 1994. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-beta and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 89-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Proetzel, G., S. A. Pawlowski, M. V. Wiles, M. Yin, G. P. Boivin, P. N. Howles, J. Ding, M. W. Ferguson, and T. Doetschman. 1995. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat. Genet. 11409-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qin, X. Q., T. Chittenden, D. M. Livingston, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 1992. Identification of a growth suppression domain within the retinoblastoma gene product. Genes Dev. 6953-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rensen, S. S., P. A. Doevendans, and G. J. van Eys. 2007. Regulation and characteristics of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic diversity. Neth. Heart J. 15100-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reynisdottir, I., K. Polyak, A. Iavarone, and J. Massague. 1995. Kip/Cip and Ink4 Cdk inhibitors cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-beta. Genes Dev. 91831-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robanus-Maandag, E., M. Dekker, M. van der Valk, M.-L. Carrozza, J.-C. Jeanny, J.-H. Dannenberg, A. Berns, and H. te Riele. 1998. p107 is a suppressor of retinoblastoma development in pRB-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 121599-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robertson, K. D., S. Ait-Si-Ali, T. Yokochi, P. A. Wade, P. L. Jones, and A. P. Wolffe. 2000. DNMT1 forms a complex with Rb, E2F1 and HDAC1 and represses transcription from E2F-responsive promoters. Nat. Genet. 25338-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robinson, G. W., K. U. Wagner, and L. Hennighausen. 2001. Functional mammary gland development and oncogene-induced tumor formation are not affected by the absence of the retinoblastoma gene. Oncogene 207115-7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanford, L. P., I. Ormsby, A. C. Gittenberger-de Groot, H. Sariola, R. Friedman, G. P. Boivin, E. L. Cardell, and T. Doetschman. 1997. TGFβ2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFβ knockout phenotypes. Development 1242659-2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sarker, K. P., S. M. Wilson, and S. Bonni. 2005. SnoN is a cell type-specific mediator of transforming growth factor-beta responses. J. Biol. Chem. 28013037-13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sellers, W. R., B. G. Novitch, S. Miyake, A. Heith, G. A. Otterson, F. J. Kaye, A. B. Lassar, and W. G. J. Kaelin. 1998. Stable binding to E2F is not required for the retinoblastoma protein to activate transcription, promote differentiation, and suppress tumor cell growth. Genes Dev. 1295-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Serra, R., and M. R. Crowley. 2005. Mouse models of transforming growth factor beta impact in breast development and cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 12749-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Serrano, M., G. J. Hannon, and D. Beach. 1993. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature 366704-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shull, M. M., I. Ormsby, A. B. Kier, S. Pawlowski, R. J. Diebold, M. Yin, R. Allen, C. Sidman, G. Proetzel, D. Calvin, et al. 1992. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359693-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sicinski, P., J. L. Donaher, S. B. Parker, T. Li, A. Fazeli, H. Gardner, S. Z. Haslam, R. T. Bronson, S. Elledge, and R. A. Weinberg. 1995. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell 82621-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sicinski, P., and R. A. Weinberg. 1997. A specific role for cyclin D1 in mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 2335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trimarchi, J. M., and J. A. Lees. 2002. Sibling rivalry in the E2F family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 311-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vandel, L., E. Nicolas, O. Vaute, R. Ferreira, S. Ait-Si-Ali, and D. Trouche. 2001. Transcriptional repression by the retinoblastoma protein through the recruitment of a histone methyltransferase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 216484-6494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van den Heuvel, S., and N. J. Dyson. 2008. Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9713-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Whyte, P., K. J. Buchkovich, J. M. Horowitz, S. H. Friend, M. Raybuck, R. A. Weinberg, and E. Harlow. 1988. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature 334124-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wrana, J. L., L. Attisano, J. Carcamo, A. Zentella, J. Doody, M. Laiho, X. F. Wang, and J. Massague. 1992. TGF beta signals through a heteromeric protein kinase receptor complex. Cell 711003-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yao, G., T. J. Lee, S. Mori, J. R. Nevins, and L. You. 2008. A bistable Rb-E2F switch underlies the restriction point. Nat. Cell Biol. 10476-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang, H. S., M. Gavin, A. Dahiya, A. A. Postigo, D. Ma, R. X. Luo, J. W. Harbour, and D. C. Dean. 2000. Exit from G1 and S phase of the cell cycle is regulated by repressor complexes containing HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF and Rb-hSWI/SNF. Cell 10179-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]