Abstract

To study when and where active genes replicated in early S phase are transcribed, a series of pulse-chase experiments are performed to label replicating chromatin domains (RS) in early S phase and subsequently transcription sites (TS) after chase periods of 0 to 24 hours. Surprisingly, transcription activity throughout these chase periods did not show significant colocalization with early RS chromatin domains. Application of novel image segmentation and proximity algorithms, however, revealed close proximity of TS with the labeled chromatin domains independent of chase time. In addition, RNA polymerase II was highly proximal and showed significant colocalization with both TS and the chromatin domains. Based on these findings, we propose that chromatin activated for transcription dynamically unfolds or “loops out” of early RS chromatin domains where it can interact with RNA polymerase II and other components of the transcriptional machinery. Our results further suggest that the early RS chromatin domains are transcribing genes throughout the cell cycle and that multiple chromatin domains are organized around the same transcription factory.

Keywords: replication sites, transcription sites, cell nucleus, computer image segmentation, proximity analysis

Introduction

The genomic processes of DNA replication and transcription have an underlying structural organization in the cell nucleus (Berezney 2002; Berezney, et al. 2005; Spector 1993). Incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in vivo or BrdUTP in permeabilized mammalian cells, reveal distinct patterns of the replicating DNA foci (RS). Each RS in early S-phase measures ~0.5 μ in diameter (Nakamura, et al. 1986; Nakayasu and Berezney 1989) and correspond to chromatin domains of approximately one megabase pairs that are maintained throughout the cell cycle and in subsequent cell generations (Berezney, et al. 1995; Jackson and Pombo 1998; Ma, et al. 1998; Sparvoli, et al. 1994). Similarly, transcription sites (TS) can be labeled in vivo by fluorouridine (FU) incorporation (Boisvert, et al. 2000) or in situ in permeabilized cells with BrUTP (Berezney and Wei 1998; Wansink, et al. 1994; Wei, et al. 1999). Extra-nucleolar transcription sites visualized by this procedure are predominantly, if not exclusively, mediated by RNA polymerase II (Boisvert, et al. 2000; Wansink, et al. 1993).

These findings have lead to the view that the 1 mega base chromatin domains represent a fundamental level of organization for the regulation and coordination of multiple genes engaged in replication and/or transcription (Berezney, et al. 2000; Jackson and Pombo 1998). Crucial to this model are previous studies including microarray based analysis of the human genome demonstrating that most of the genes replicating in early S phase are actively transcribed in higher eukaryotes (Goldman, et al. 1984; Hatton, et al. 1988; MacAlpine, et al. 2004; Schubeler, et al. 2002). Major players in determining these properties of a gene are the chromatin configuration and the epigenetic modifications. Specific examples have been reviewed explaining the complex scenarios shaping up this ‘nuclear landscape’ (Chakalova, et al. 2005; Gilbert 2002; McNairn and Gilbert 2003; Schwaiger and Schubeler 2006; West and Fraser 2005). In addition, the functional domains involved in gene expression and replication are dynamically linked to nuclear structure and organization (Berezney 2002; Lanctot, et al. 2007; Stein, et al. 2003; Zaidi, et al. 2007)

The correlation between replication timing and gene activity (Goren and Cedar 2003; Schwaiger and Schubeler 2006) suggests that genes replicated in early S-phase are potentially important models for deciphering the possible coordination of replication and transcription processes. Observations from 3-D data sets indicated that the zones of replication and transcription were organized into discontinuous network-like arrangements that did not overlap but were in juxtaposition at many regions (Berezney and Wei 1998). These findings suggested models for the spatio-temporal coordination of DNA replication and transcription in the mammalian cells involving a programmed zoning of chromatin into active RS and rezoning into active TS as the cell progresses through S-phase (Berezney 2002; Berezney and Wei 1998; Cook 1998).

These previous findings raise the question: if active genes are replicated at discrete RS in early S phase, then when and where are these genes transcribed? To address this question, we have conducted a series of pulse-chase experiments to label RS and subsequently TS under both in vivo and in situ conditions. Our results were unexpected and have led us to propose a model for the spatial positioning of gene transcription in relation to the early S-replicated chromatin domains.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

All the experiments were performed on exponentially growing HeLa cells [ATCC number CCL-2] in Advanced DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with Gluta-Max™, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin antibiotic solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 2.5% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were grown (37° C and 5% CO2) on glass cover slips (12CIR-1, Fisher Scientific) 12–15 hours before the experiments.

In vivo labeling of replication and transcription sites

For simultaneous labeling of RS and TS, cells were pulsed with BrdU (20 μM) and FU (1 mM) for 7 and 12 min respectively. For pulse-chase experiments, the BrdU pulse was followed by the FU pulse after different chase times (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 15 and 24 hr). Following incorporation of nucleotide analogs, all treatments were performed at room temperature and included washing the cells with 1X PBS, fixation with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Pre-blocking with 10% fetal bovine serum for 20 min was done before proceeding with antibody labeling. Transcription sites (TS) were labeled by sequential incubations with rat anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (1:50 dilution, Sera-Lab, Crawley Down, UK) followed by anti-rat-IgG conjugated to Alexa 594 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following post-fixation (4% paraformaldehyde, for 8 min), the samples were treated with 4N HCl for 12 min to make accessible BrdU incorporated sites of replication (RS) to sequential antibody labeling with mouse anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution) and anti-mouse IgG antibody coupled to Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

In vivo labeling of RS and in situ labeling of TS

Exponentially growing HeLa cells on glass cover slips were pulsed with CldU (20 μM) for 7 min to label replication sites and then washed with ice-cold TBS buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 5 mM MgCl2), followed by glycerol buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 25% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM PMSF) for 10 min on ice. Washed cells were permeabilized with 0.025% Triton X-100 in glycerol buffer (with 25 U/ml of RNasin; Promega Corp.) on ice for 3 min and immediately incubated at room temperature for 30 min with nucleic acid synthesis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 25% glycerol, 0.5 mM PMSF, 25 U/ml of RNasin (Promega), 1.8 mM ATP) supplemented with 0.5 mM CTP, GTP, and BrUTP (Sigma Chemical Co) to label transcription sites. After incorporation of the respective nucleotide analogs to label RS and TS, cells were fixed for 10 min at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Incubations with rat and mouse anti-BrdU antibodies and subsequently secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorochromes were used to label CldU (RS) and BrUTP (TS) sites.

In vivo labeling of TS and RNA polymerase II sites

Following the incorporation of FU (for labeling TS), cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Pre-blocking with 10% fetal bovine serum for 20 min was followed by incubations with monoclonal rat anti-BrdU (1:50 dilution) and mouse anti-RNA polymerase II IgG antibodies (1:100 dilution, ARNA-3, RDI division of Fitzgerald industries). Rat and mouse primary antibodies were detected with specific secondary antibodies conjugated fluorochromes as described in previous section. Control experiments assessing the colocalization of signals from total endogenous pol II and hyper-phosphorylated form of pol II were performed by simultaneous incubation with ARNA-3 and B3 (mouse IgM mAb, (Mortillaro, et al. 1996)) antibodies and subsequent detection with specific secondary antibodies.

In vivo labeling of RS and RNA polymerase II sites

BrdU (for labeling RS) incorporated cells were followed by different chase times (0, 1 and 12 hr) and fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature. Permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min was followed by pre-blocking with 10% fetal bovine serum for 20 min at room temperature. RNA Pol II sites were detected by sequential incubations with mouse anti-RNA polymerase II IgG antibodies (1: 100 dilution) and anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A post-fixation step with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature preserves the labeled RNA polymerase II sites before the samples were treated with 4N HCl for 12 min. RS were detected by sequential incubations with monoclonal rat anti-BrdU antibodies and anti-rat IgG secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa594 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

In vivo labeling of TS and two populations of RS

HeLa cells were pulsed with CldU (20 μM) for 7 min to label the first population of RS. After a chase period of 2 hr cells were pulsed with FU (1 mM) and IdU (20 μM) for 12 and 7 min respectively to label TS and a second population of RS. Following the incorporation of nucleotide analogs cells were washed with 1X PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. Pre-blocking was followed by sequential antibody incubations with sheep anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (1:30 dilution, Biodesign Inc., USA) and anti-sheep-IgG conjugated to Alexa488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following post-fixation (4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min) and depurination of DNA (4N HCl for 12 min), samples were incubated sequentially with rat anti-BrdU (1:50 dilution, Sera-Lab, Crawley Down, UK) and mouse anti-BrdU (1:100 dilution) antibodies. A high salt buffer (0.5 M NaCl; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; and 0.5% Tween 20) wash was used to remove low affinity cross-reactive rat anti-BrdU antibodies prior to incubation with mouse anti-BrdU antibodies (Ma, et al. 1998). Anti-rat and mouse IgG antibodies coupled to Alexa594 and Alexa647 respectively were used to label CldU and IdU incorporated RS.

Three-Dimensional microscopy and Computer Image Analysis

Cover slips with labeled cells were mounted in Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Specific indirect immunofluorescence was detected with Chroma filter sets using an Olympus BX51 upright microscope (100xplan-apo, oil, 1.4 NA) equipped with Sensicam QE (Cooke Corporation, USA) digital CCD camera, motorized z-axis controller (Prior) and Slidebook 4.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). 0.5 μ optical sections were typically collected and processed using nearest-neighbor deconvolution (Slidebook 4.0) and exported as 16 bit tiff intensity files for further analysis.

Spot-based segmentation, proximity analysis and the cross correlation function (ccf)

Segmentation of the RS, TS and other labeled foci were performed using a recent modification (Bhattacharya, et al. 2005) of our spot based approach (Ma, et al. 1998; Samarabandu, et al. 1995) which enables an even more accurate segmentation of relative small sites (diameter < 0.5 microns) including those which are very close together and that vary widely in intensity. In this knowledge based algorithm, for all the slices in an image, 2D boundaries are formed around initially detected local intensity maxima which are above noise levels. A cost array using estimated edge strengths in the image is constructed and the boundaries are formed by computing a minimum cost path (Bhattacharya, et al. 2005). After completion of 2D boundary detection, a 3D labeling algorithm is applied to form the true three dimensional objects. The new center of each object is then calculated as the center of gravity (centroid).

Proximity analysis of two sets of functional sites for the same nucleus is performed on the centroids (i.e. geometric centers) of the site contours computed from our segmentation algorithm. In the first step, centroids from one set are used to divide the space within the nuclear image by the Quickhull algorithm (Barber, et al. 1996) into polygonal cells known as Voronoi polygons. These polygons have the following properties: the area on the nuclear image is fully covered by the union of these polygons; each polygon contains exactly one centroid and all points internal to a certain polygon are closer to the centroid located inside it than to any other centroid. In the next step, centroids from the other set are taken and geometric tests are performed to determine which polygon they belong to. This step thus provides the answer to the following question: given a site in the second set which site in the first set is it closest to? After computing this closest site relationship our proximity analysis algorithm calculates the list of all distances (measured as length of the line connecting centroid to centroid) between the sites in the second set to their closest sites in the first set. The algorithm is thus able to provide the answer to the following question by a simple scan of this list: what percentage of sites from the second set are closer than a certain distance to a site in the first set? We then express our data as the percentage of transcription sites that are proximal to the replication sites over a range of distances. MATLAB code implementing the algorithms is available upon request.

We also applied the cross correlation function (CCF) method (van Steensel et. al., 1996) to evaluate overlap between sites. For this analysis we first generated cytofluorograms by plotting the grey values of pixels in red and green channel images against each other (JACoP plugin of ImageJ). Pixels residing along the red diagonal trend line in the resulting scatter plot indicate colocalization. Pixels that are away from the red diagonal indicate exclusion (Bolte and Cordelieres 2006). For CCF analysis, the green image is shifted in x-direction pixel per pixel relative to the red image. The Pearson’s coefficients at each stage are then plotted along the x-axis resulting in a CCF (Grande, et al. 1997; van Steensel, et al. 1996). If the peak of the curve coincides with 0 pixel shift represented by the red base line, it is indicative of colocalization. If the red base line is associated with a dip, it suggests exclusion. If the resulting peak or dip is off the base line by few pixels, it suggests an overall partial colocalization in addition to exclusion or colocalization. Though CCF efficiently describes the overall trend of colocalization between two images in comparison (Bolte and Cordelieres 2006), images with high density of sites and various extents of colocalization are not completely quantified using this approach. The proximity analysis developed in this study is especially designed to address these issues.

Results

Imaging replication and transcription sites following pulse-chase-pulse labeling

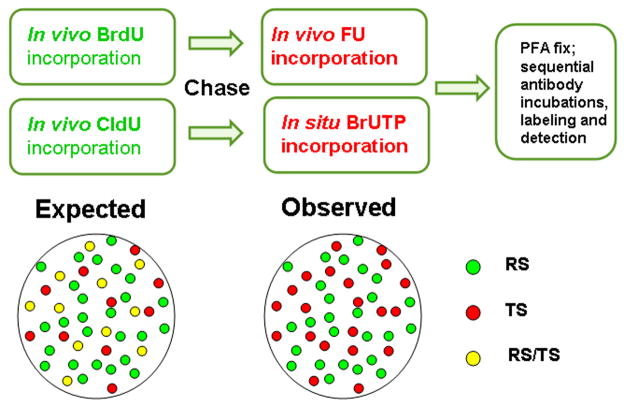

A series of pulse-chase-pulse experiments were initiated to determine when the early S phase replicated genes are transcribed. Figure 1 outlines the overall strategy for the dual labeling of DNA replication (RS) and transcription (TS) sites in exponentially growing HeLa cells. The experiments were performed in two ways. For in vivo labeling of TS, cells were initially labeled with BrdU (RS), chased for periods ranging from 0 to 24 hr followed by FU incorporation for TS (Boisvert, et al. 2000; McManus, et al. 2006). For in situ labeling of TS, cells were pulsed with CldU, permeabilized (see Materials and Methods) and labeled for TS with BrUTP (Wei et al, 1998). This latter permeabilized cell system is known to minimize the translocation of nascent transcripts from the place of synthesis (Wei, et al. 1998). Dual labeled cells showing the characteristic patterns of early S replication (Ma, et al. 1998; Nakayasu and Berezney 1989) were then selected for further analysis. Overlay of the red and green channels and subsequent identification of yellow sites (as illustrated in ‘expected results’ of Figure 1) should indicate early RS chromatin domains that are now actively engaged in transcription. Surprisingly, we found that the RS and TS continued to display separate red and green signals with no significant yellow colocalization (as schematically illustrated in Figure 1) in the more than one dozen experiments that were performed over a full range of chase times (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 15, 18 and 24 hr) for either in vivo or in situ labeling of TS. Representative results of these experiments are shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 1. The labeling scheme of replication sites (RS) and transcription sites (TS).

Nucleotide analogs are incorporated in living cells (referred to as in vivo labeling) or permeabilized cells (referred to as in situ labeling); following the protocols described in the Materials and Methods Section, the predicted and observed distributions of RS and TS for both in vivo and in situ approaches are represented as a cartoon. The legend describes the colors assigned to the RS, TS and the expected merged sites.

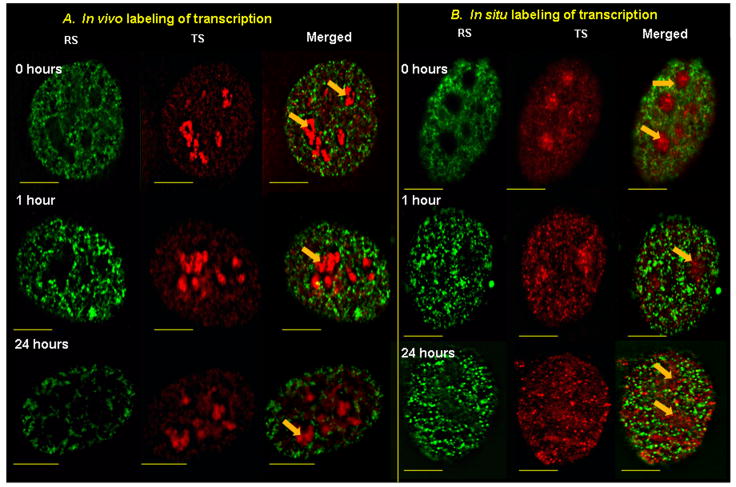

Fig. 2. Spatial distribution of RS and TS.

Double labeling experiments of early S-phase replication sites (RS) and nascent transcript sites (TS) in HeLa cells. Association of early S phase RS in randomly dividing HeLa cells with TS were examined 0, 12 and 24 hours after incorporating BrdU nucleotide analogs. In the left panel (A) RS (green) were labeled by BrdU and subsequently TS (red) were labeled by FU incorporations (in vivo conditions) after different chase periods of 0, 12 or 24 hours. In the right panel (B), after the incorporation of CldU (green) cells were permeabilized and after different chase periods, labeled for TS (red) by incorporating BrUTP (in situ conditions). Merged column in both panels shows RS in green and TS in red; orange arrows represent intensely labeled nucleolar TS; note the lack of yellow color in the merged column which indicates the absence of significant colocalization; yellow scale bars indicate a distance of 5 microns.

Point-based segmentation analysis of early RS chromatin domains and TS

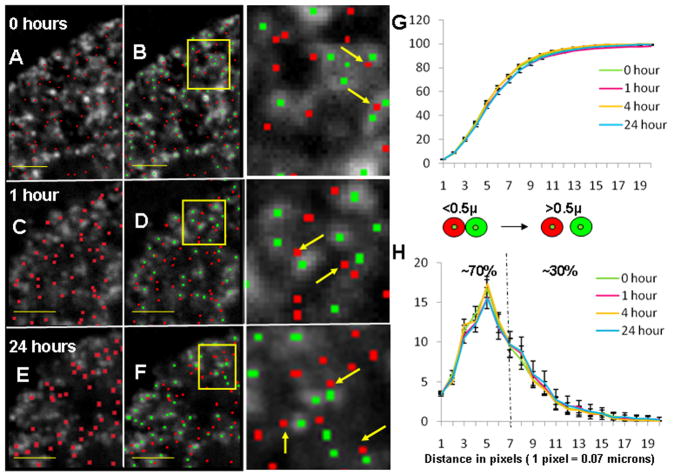

The inability to observe conversion of RS to TS by a color change to yellow sites led us to develop an approach to directly measure the spatial position of labeled TS in relation to the RS labeled chromatin domains. As a first step, early RS labeled chromatin domains and TS were segmented by an improved version (see Materials and Methods) of our spot based segmentation (Samarabandu, et al. 1995). This segmentation program accurately segments sites that are very close together as well as varying widely in signal intensity (Samarabandu, et al. 1995). Figure 3 shows representative results of this analysis in which, the centroids (center of gravities) of each segmented TS (red) and RS (green) are displayed over the original grey scale image of the early RS chromatin domains (Fig. 3A to F). Irrespective of the chase time, TS centroids in the nucleoplasmic regions excluding the nucleoli are typically in close association with the discrete RS without showing colocalization (Fig. 3B, D & F). The apparent close proximity of labeled TS with previously labeled RS is further supported by dual display of the RS and TS centroids over the original RS labeled sites (Fig. 3B, D & F for 0, 1 and 24 hr chase periods, respectively). We routinely observed that the great majority of TS centroids (>75% by manual counting) were positioned at or close to the periphery of the raw signals for discrete chromatin domains. When small areas of Figure 3B, D & F were enlarged and closely examined, we found that the closest of the RS and TS neighbors, whose center to center distance is less than or equal to 3 pixels (≤ 0.2 μ), continued to show only partial colocalization and that these closest of neighbors were among the smallest sites in the total population which overall ranged from 0.2–0.8 microns in diameter with an average of 0.45 microns (Ma, et al. 1998). Moreover, the closely associated TS centroids were always positioned at or very close to the periphery of the chromatin domain sites. We also observed many instances of TS centroids being proximal to more than one RS.

Fig. 3. Spatial distribution of replication sites (RS) and transcription sites (TS) following segmentation and proximity analysis.

The raw RS signal in grey scale at 0, 1 and 24 h respectively are overlaid with red colored TS centroids (A, C & E); the grey scale raw RS signal overlaid with red TS centroids and green RS centroids (B, D & F). Portion of (B, D & F) are enlarged in the adjacent column; yellow arrows indicate TS centroids which are at closer distance (≤ 0.2 microns) to RS centroids without direct colocalization; yellow scale bars indicate a distance of 2 microns. Centroid positions were calculated using spot based segmentation (see Materials & Methods section). (G) Shows the cumulative plot of percentage proximity values of TS to RS on Y axis and the distance (in pixels) on X axis. All the 4 chase times show a similar relationship. Standard error bars are indicated where necessary (n= 26, 46, 27 and 35 for 0, 1, 4 and 24 hours respectively). (H) Shows the distribution of proximity percentages for the above mentioned categories. The schematic above the plot shows red and green sites with their respective centers. Two different categories of proximity are indicated where the center to center distance 1) is less than 0.5 μ (70% TS) and 2) is more than 0.5 μ (30% TS).

Proximity Analysis of TS to RS Chromatin Domains

To directly measure the close association of RS and TS, we developed a new spatial proximity program that determines the distance between each individual sites (center to center distance between centroids) within one population of sites with its “nearest neighbor” in another population of labeled sites (see Materials and Methods). The number or percent of total TS that are within a certain distance or proximity of their nearest neighbor early RS chromatin domain is then determined over a range of pixel distances. Using as a control, 0.5 micron dual labeled red/green fluorescent beads which approximate the average size of RS and TS (Ma, et al. 1998), our nearest neighbor proximity program calculated that 86% of the red and green signals were within 1 pixel (0.07 micron) of each other. This increased to 100% at 2 pixels (0.14 microns) and higher and supports the validity of this approach (see S1). Figure 3G shows the proximity profiles of TS to early RS chromatin domains following 0, 1, 4 and 24 hr chase times. The majority of the total TS centroids (≥ 70%) are within 7 pixels (0.5 microns) of the nearest neighbor RS centroids, and over 80% are within 10 pixels (0.7 microns; Fig. 3G). These findings demonstrate a high degree of proximity between early RS chromatin domains and TS which are maintained throughout the cell cycle.

To gain further insight into these spatial relationships, we plotted the proximity as the percent distribution of TS at each measured pixel distance (Fig. 3H). Approximately 70% of the TS centroids were within 7 pixels (0.5 microns) of their nearest RS centroid. 0.5 microns is the center- to-center distance for two 0.5 micron diameter sites which are just touching (juxtaposed). Since the RS and TS have average diameters in that size range (Ma et al., 1998, and results not shown), many of the sites that are within 7 pixels would range in association from significant partial overlap to juxtapositioning and thus define a ‘zone of association’. About 30% of the TS centroids had nearest RS centroids >7 pixels apart. This contains that population of TS and RS that are not significantly associated. A minor percentage (< 10%) of this latter category are RNA polymerase I mediated nucleolar TS.

Proximity analysis of TS/RS to RNA polymerase II

We next asked the question, “If pre-labeled RS (template) have only low levels of colocalization with the TS (product of transcription), how are RNA polymerase II (pol II) sites (enzymatic mediators) organized relative to the RS and the TS?” We performed double labeling for pol II along with TS or RS and determined their proximity relationships. While these experiments were performed with an antibody (ARNA3) that recognized both hyper- and hypo-phosphorylated forms of the largest subunit of pol II, a similar staining pattern was obtained for pol II sites, with the B3 antibody (see S2) which is specific for the hyperphosphorylated form (Mortillaro, et al. 1996; Patturajan, et al. 1998). Line profile analysis of a central and peripheral region of the nucleus indicated that B3 (green) and ARNA3 (red) line profiles correlate highly with each other except for minor differences in intensity (see S2). This is in agreement with previous studies (Bregman, et al. 1995; Warren, et al. 1992) add Grande et al., 1997 here?? and the suggestion that pol II sites in the nucleus might be composed of both forms of polymerases (Bregman, et al. 1995; Zeng, et al. 1997).

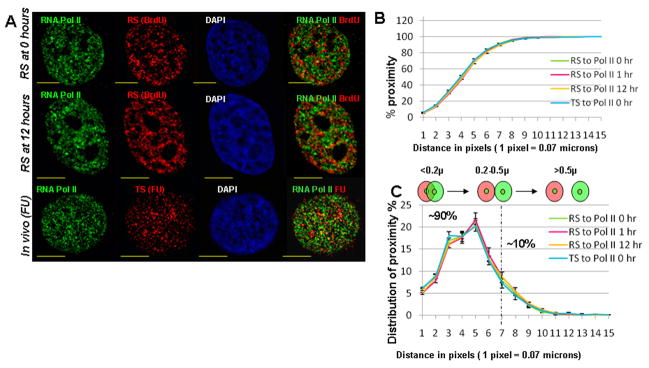

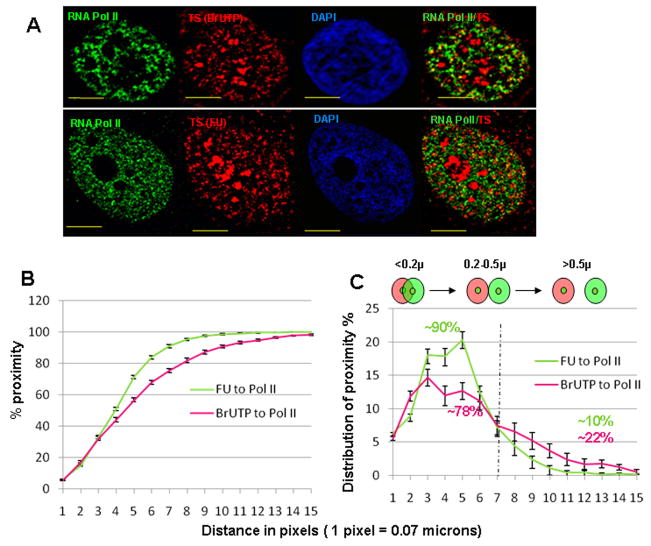

Representative images (Fig. 4) showed very limited yellow color when images of pol II sites (green) were merged with either TS (FU incorporation, red) or RS chromatin domains (BrdU incorporation, red) at 0 or 12 hr chase times. Despite this, there was a very high proximity relationship for pol II sites with both TS and RS chromatin domains (Fig. 4B). Over 90% of TS and RS labeled chromatin domains had center to center distances (proximities) within 0.5 microns (Fig. 4C), independent of the chase times following BrdU incorporation (0 and 12 hr). These results, unlike direct observation of the merged raw images, are indicative of at least a partial overlap of pol II sites with nascent transcript sites and early S phase replication labeled chromatin domains.

Fig. 4. Proximity analysis of TS or RS to pol II sites.

Representative mid plane sections from the immuno-fluorescence labeling experiments are shown (A). Top row of (A) shows pol II (green), RS (red) and DAPI (blue) followed by the merged channel indicating pol II (in green) and RS (in red); middle row of (A) shows results of labeling RS and pol II after a 12 hour chase period; bottom row of (A) shows the results of simultaneous labeling of pol II and TS (FU). Endogenous RNA polymerase II in all three rows is labeled with primary mouse anti-RNA pol II antibody (ARNA3). Yellow scale bars indicate a distance of 5 microns. (B) The cumulative plot of percentage proximity values of TS or RS to pol II on Y axis and the distance (in pixels) on X axis. All 4 trends (see legend) show a similar relationship. Error bars indicate the SEM values; (n= 21, 30, 14 & 15 for TS to pol II, RS to pol II at 0, 1, and 12 hr time points respectively). The schematic below the plot shows red and green sites with their respective centers. (C) Two categories of proximity are indicated in the distribution plots of proximity percentages; proximity % values for each category were approximately 90% & 10%, respectively.

Proximity analysis of TS to RNA polymerase II sites in vivo and in permeabilized cells

Numerous investigations have used permeabilized cells to study transcription sites in the cell nucleus (Elbi, et al. 2002; Jackson, et al. 1993; Wansink, et al. 1993; Wei, et al. 1999). It was, therefore, of interest to determine to what extent the proximity relationships that we have found for TS to pol II sites are maintained following permeabilization. Dual labeling experiments of FU incorporation in vivo and BrUTP incorporation in permeabilized cells were performed along with pol II antibody labeling. The results shown in Figure 5 demonstrate similar staining patterns for TS including the characteristic very intense staining of pol I sites in the nucleolar interior. The overall features of the pol II staining also appear similar for in vivo versus permeabilized labeled cells including the exclusion of pol II from the nucleolar regions. Quantitation of the number of pol II sites following segmentation of the images revealed that about one third (33.6%) were extracted during the permeabilization, while the number of detected TS slightly increased (11%) following permeabilization.

Fig. 5. Proximity analysis of TS to pol II for intact and permeabilized cells.

Representative mid plane sections from the immuno-fluorescence labeling experiments are shown in (A). FU sites and BrUTP sites represent the TS in intact and permeabilized systems. Endogenous RNA polymerase II in both rows is labeled with primary mouse anti-RNA pol II antibody (ARNA3). Yellow scale bars indicate a distance of 5 microns. (B) and (C) show the cumulative proximity plot of TS to pol II and distribution plot for same data; in the legend, FU to pol II (n=21) and BrUTP to pol II (n=21) indicated in vivo and in situ (permeabilized) experimental conditions. Error bars indicate SEM values.

Despite the apparent low level of colocalization of TS and pol II sites indicated by the limited yellow color (Fig. 5A), there was a high degree of proximity of TS to pol II for both in vivo and permeabilized cells (Fig. 5B). For example, those TS closest to pol II sites (<0.2 microns) were found at a similar distribution (~35%) in permeabilized and intact cells (Fig. 5B). There was a small decrease in the relative proximity in permeabilized versus intact cells at distances between 0.2–0.5 microns (Fig. 5B) so that e.g., at a 7 pixel distance (~0.5 microns) nearly 90% of in vivo labeled TS had a pol II proximity partner compared to < 80% for those in permeabilized cells (Fig. 5C).

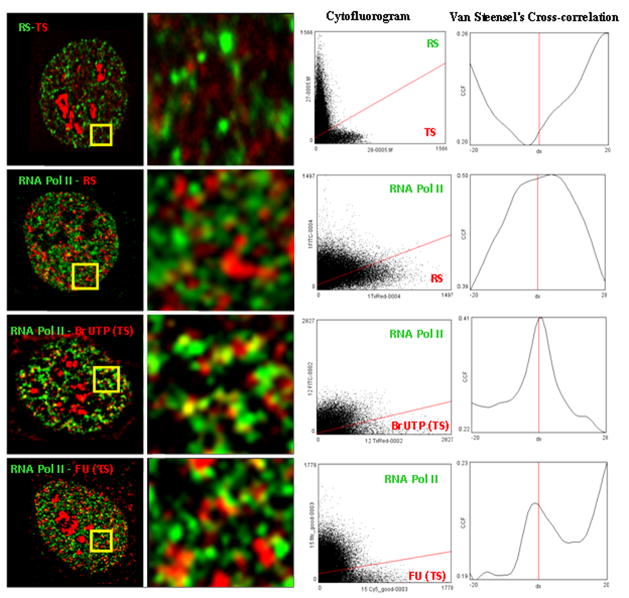

Colocalization analysis of TS, RS and pol II domains Our proximity analysis reveals a high degree of proximity in the cell nucleus of RS, TS and pol II sites despite the relative absence of yellow color which is “diagnostic” of co-localization. There are alternative explanations for these findings. For example, RS and TS may indeed show only limited partial overlap but have a very high degree of juxtapositioning of sites. It is also possible that there is much more overlap (co-localization) between these sites than can be seen by direct visualization. Similarly, it is difficult to understand why pol II sites do not show high levels of co-localization with TS. To more precisely evaluate the degree of overlap between these sites, we applied the CCF method for evaluating co-localization between different populations of sites based on analysis of total pixel populations (see Materials and Methods for details and refs). The cytofluorograms of the total pixel pospulation (Fig. 6) describe the global trend of overlapping pixels in red and green channels. The results strikingly demonstrate a negative correlation (lack of co-localization) between RS and TS as indicated by the negative dip at the zero pixel baseline (Fig. 6B). In contrast, RS to pol II, TS (BrUTP) to pol II and TS (FU) to pol II showed a positive CCF (presence of co-localization) as indicated by peaks at or near the 0 pixel base line (Fig. 6D, F and H). Moreover, the peaks or dips fall immediately adjacent to the 0 pixel base line in the CCF plots which further suggests an overall partial overlap in case of colocalization or exclusion (Bolte and Cordelieres 2006).

Fig. 6. Colocalization analysis of RS, TS and pol II sites.

Portions (yellow square) of representative mid plane sections of RS-TS (0 hour chase), pol II RS, pol II TS (BrUTP) and pol II TS (FU) labelings are enlarged to demonstrate the extents of colocalization and variations in intensities among red and green channel sites. Cytofluorograms describe the distribution of red and green pixels from respective channels of images. RS TS show a predominant exclusion compared to partial to complete colocalization seen in other cases of comparisons. Van Steensel’s CCF (cross correlation function describes the overall trend of colocalization for the double labeled images (see Materials and Methods for details).

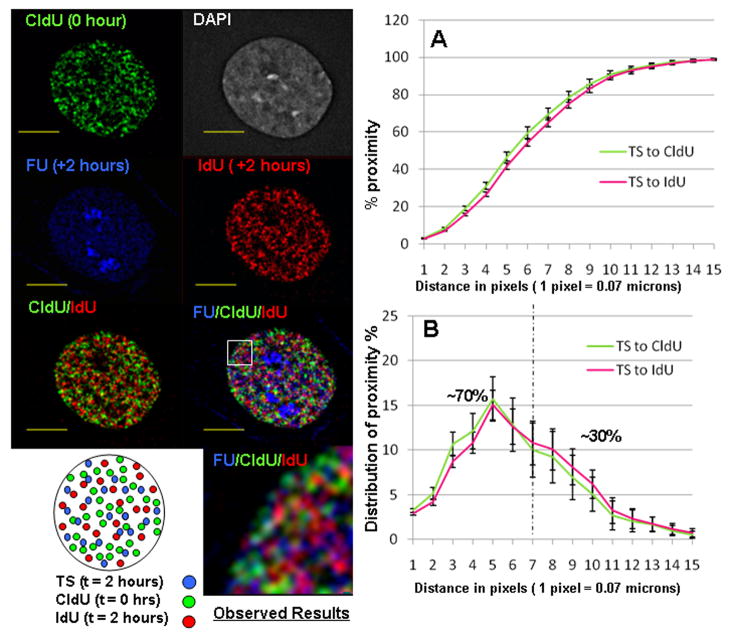

Proximity analysis of TS to RS chromatin domains replicated at different times in early S-phase

As previously reported, RS labeled at two hours intervals in early S phase are completely separated based on direct observations of merged images and 3-D computer analysis following segmentation (Ma, et al. 1998; Sadoni, et al. 2004). We, therefore, performed triple labeling experiments in which CldU was incorporated at 0 hours followed by a chase period of 2 hours. A second simultaneous pulse of IdU and FU was then performed to label a second population of RS and TS (see Materials and Methods for details).

Representative mid-plane optical sections for these experiments are shown in Figure 7. Merging of the CldU (green) and IdU (red)-labeled sites reveals that the two populations of RS labeled chromatin domains are spatially distinct with virtually no yellow color or overlap. Further merging with the FU labeled TS shows that the TS are largely spatially separate from both populations of labeled RS chromatin domains (Fig. 7). Proximity analysis was then performed from TS to each spatially distinct population of RS labeled chromatin. As shown in Figure 7A and B, the overall proximity relationship of TS to each population of RS labeled chromatin domains is very similar. The minor differences are likely due to variations in the experimental conditions for labeling and imaging. Comparison of the distribution of proximity among the TS with the associated (< 0.5 microns) to more distal non-associated sites are also very similar for the two populations of RS. For example, the associated populations (< 0.5 microns) were 70% versus 65% for the CldU and IdU-labeled sites, respectively.

Fig. 7. Proximity Analysis of TS to two RS populations (CldU & IdU Sites).

Representative mid plane sections from the immune-fluorescence labeling experiments of TS and RS labeled simultaneously (0 h chase between FU and IdU incorporations) and RS labeled 2 hours earlier (2 h chase between CldU and IdU). Exponentially growing HeLa cells are incorporated with CldU at 0 hours and chased for 2 hours. Cells are then pulsed with FU and IdU to label TS and a second population of early S RS, respectively. Observed results are schematized in a cartoon (bottom left). CldU RS, IdU RS and TS are labeled in green, red and blue colors, respectively. Results show that most of the red, green and blue sites are distinctly separated with partial areas of overlap along the border regions. Yellow scale bars indicate a distance of 5 microns. (A) Cumulative and (B) distribution plots describe the proximity relation between the TS to CldU sites, TS to IdU sites, TS to CldU and IdU together; (n=14); error bars indicate SEM values.

Discussion

Association of replication and transcription sites in the cell nucleus

Previous studies have established that the individual sites of DNA replication and transcription are spatially segregated throughout the S phase of the cell cycle (Wansink, et al. 1994; Wei, et al. 1998). Moreover, these key genomic functions are organized into ‘nuclear zones or neighborhoods’ which may provide the basis for replicational and transcriptional programming in the cell nucleus (Berezney 2002; Wei, et al. 1998). The aim of this study was to define spatio-temporal properties of the transcriptionally active genes replicated during early S phase. To investigate this question, we utilized a double pulse chase experiment that incorporated halogenated nucleotide analogs into newly synthesized strands of nucleic acids with subsequent detection using specific antibodies. Since it is known that early S replicating chromatin domains are enriched in actively transcribing genes (MacAlpine, et al. 2004; Schubeler, et al. 2002; Woodfine, et al. 2004), we expected to see yellow sites representative of the transcriptional activity of genes which encompassed these previously labeled chromatin domains. On the contrary, for various chase periods of 0 to 24 hours, we did not find any significant colocalization (yellow color) as determined by direct visual observation, cytofluorograms and CCF (Fig. 6) between previously labeled early S chromatin domains (green) and nascent transcript sites (red) (Fig. 2).

This led us to investigate the association of early RS chromatin domains and TS, using spot-based segmentation and a newly developed proximity analysis. The segmentation analysis revealed that the centroids for the TS were preferentially associated along the borders of the early RS chromatin domains but never directly co-localized with the RS centroids. A close association was demonstrated by proximity analysis where ~70% of the TS had a nearest neighbor RS centroid with a center-to-center distance of less than 0.5 microns. This high level of proximity was conserved for various chase times of 0 to 24 hr between RS and TS labeling. The very limited direct co-localization of RS and TS, however, was further supported by a negative correlation following the cytofluorogram and CCF analysis (Fig. 6)

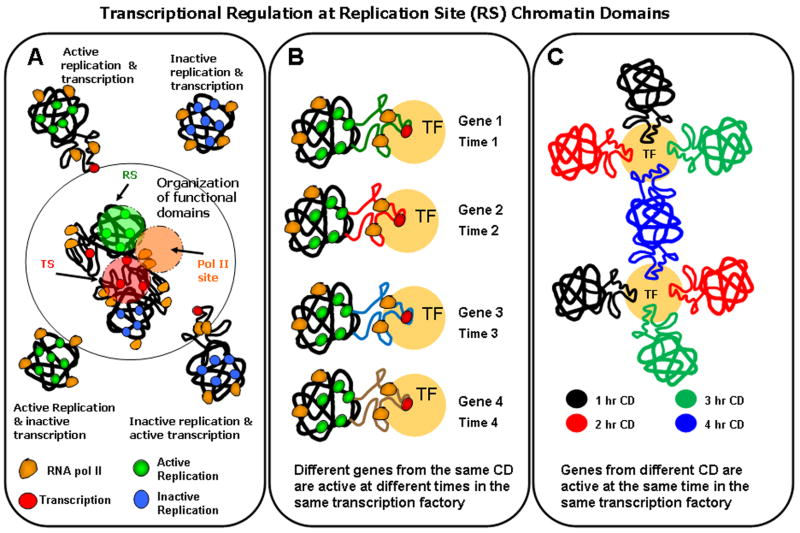

Based on our proximity data, we propose that chromatin activated for transcription, dynamically unfolds or “loops out” of densely packed discrete chromatin domains (Fig. 8A & B) where it engages in active transcription within “transcription factories” (Jackson, et al. 2000; Pombo, et al. 2000). It is possible that the local configuration changes from more condensed (discrete) regions of individual chromatin domains, into more diffuse (decondensed) regions occurs during activation of gene transcription. Several studies have indicated the unfolding/folding of chromatin domains during the activation or inactivation of both artificial and endogenous gene loci (Bickmore, et al. 2004; Chambeyron and Bickmore 2004; Chambeyron and Bickmore 2004; Mahy, et al. 2002; Mahy, et al. 2002; Tumbar and Belmont 2001; Volpi, et al. 2000). Electron microscopic observations have suggested extensive regions in the nucleus that are devoid of 10 and 30 nm chromatin fibers (Dehghani, et al. 2005). A recent study by Cremer and colleagues concluded that nascent RNA and pol II sites are enriched in this interchromatin compartment and show high proximity to the neighboring chromatin domains (Albiez, et al. 2006). It was further suggested that chromatin containing active genes unfolds into this interchromatin compartment during transcription (Albiez, et al. 2006). Our findings extend this analysis to the global level of the genome and suggest that chromatin unfolding may be a fundamental event required for transcriptional activation. The highly proximal positioning of the TS to the previously labeled chromatin domains and lack of direct colocalization also indicates that the de-condensed DNA that extrudes out of chromatin domain is not dense enough to be directly detected.

Fig. 8. Transcriptional regulation at replication site (RS) chromatin domains.

A hypothetical model extends our understanding of the 1 Mbp chromatin domains and the coordination of replication and transcription. (A) Chromatin domains are either active or inactive for replication and transcription giving rise to various possible configurations as depicted. Active and inactive replication is represented over chromatin domains with green and blue colored circles, respectively. Transcriptional activity and pol II are visualized as red and orange colored circles, respectively. Despite the absence of colocalization (yellow color), proximity analysis revealed a high degree of spatial association between RS and TS (Fig. 2 & 3). These results led us to propose that genes encompassing the chromatin domains either active or inactive for replication (green or blue), loop out or decondense, when activated for transcription (red). Based on proximity results, some pol II (orange) are placed at ~ equal distance from both chromatin domains and transcriptional activity. (B) Proximity analysis of pulse-chase experiments also suggests that different genes from the same chromatin domain are active at different times in the same transcription factory. (C) Our analysis also suggests that genes from different temporally labeled subsets of chromatin domains are active at the same time in the same transcription factory. The organization of functional domains is also illustrated in (A) where transcription factories are visualized as the product of the genes encompassing different chromatin domains.

It has also been suggested that gene transcription occurs stochastically in bursts of activity throughout the cell cycle (Chubb, et al. 2006; Levsky, et al. 2002; Levsky and Singer 2003; Raj, et al. 2006). ADD Ross, 1994 [paper for discontinous or “burst” transcription] referenced in Grande, 1997 paper. Using multi-FISH approaches, Singer and colleagues have directly visualized this process using a series of gene probes (Levsky, et al. 2007; Levsky, et al. 2002). With this in mind, we propose that the constant high level of transcription associated with the early RS chromatin domains is a manifestation of burst transcription in which different subsets of genes within each chromatin domain are unfolded and activated for transcription at different times over the cell cycle (Fig. 8B). The final result of this stochastic process at the level of individual chromatin domains is that all the active genes within the domain are transcribed at different times and at the required levels for the given cell.

Using FISH studies of individual genes, several investigations have demonstrated that distally located genes along a chromosome or between chromosomes cluster together at transcription factories (Fraser 2006; Ling, et al. 2006; Mitchell and Fraser 2008; Nunez, et al. 2008; Osborne, et al. 2004). Our determinations of high levels of close proximity of transcription sites to the early S chromatin domains is consistent with this finding and suggest that assembly/activation of these dynamic transcription factories containing distally located genes may be a fundamental event involved in the regulation of transcription at the global level of the genome. To further explore this possibility we performed proximity measurements of TS compared with two temporal populations of early S labeled RS (Fig. 7). Since this by definition must represent two different subsets of actively transcribed genes, our finding of identical proximity of transcription sites to each temporal population of labeled chromatin domains, is likely reflecting the participation of genes from different chromatin domains (i.e., distal genes) at common transcription factories as illustrated in Figure 8C.

Our model (Fig. 8A) also predicts that transcription can occur simultaneously with replication at chromatin domains but without colocalization at the discrete RS due to the unfolding of the transcriptionally active regions of the chromatin domain. The chromatin domains are either active or inactive for replication and transcription giving rise to several possible states as depicted in the schematic. For simplicity, we depicted the position of pol II sites as equidistant from both replicational and transcriptional activities as indicated by the proximity values (Fig. 8A). To produce the large number of transcripts of abundantly transcribed genes, it is conceivable that these genes are maintained in an unfolded (diffuse) state for prolonged periods of time within a transcription factory. In contrast genes that are transcribed only a very limited number of times per cell cycle (e.g. 1–10 copies) may need to be in a more diffuse chromatin state for transcription for only very limited number of times in each cell cycle. This less abundantly transcribed class of genes, which composes the vast majority of transcribed genes in a typical mammalian cell (Chubb, et al. 2006; Shav-Tal, et al. 2006) may, therefore, reversibly extend into the transcription factories surrounding the early RS replicated chromatin domains for active transcription and fold back into the RS following termination of transcription (Fig. 8A). Several previous studies employing FISH have demonstrated massive chromatin unfolding of individual genes following transcriptional activation (Chambeyron and Bickmore 2004; Mahy, et al. 2002; Ragoczy, et al. 2003; Tumbar and Belmont 2001; Volpi, et al. 2000).

Association of replication and transcription sites to RNA polymerase II sites: the Transcription Factory

Although electron microscopy analysis has demonstrated that the nascent transcript sites (TS) can be visualized around the borders of condensed chromatin (Cmarko, et al. 1999; Fakan 1971; Iborra, et al. 1996; Wansink, et al. 1996), their exact position with respect to the RNA polymerase holoenzyme complexes has not been elucidated. A previous study in HeLa cells showed that the number of pol II sites is greater than those of TS and that not all pol II sites are associated with corresponding TS and vice versa (Grande, et al. 1997). Pol II sites have also been visualized adjacent to the clusters of nascent transcripts by electron microscopy techniques (Iborra, et al. 1996). The pol II sites were subsequently referred to as transcription factories and it was hypothesized that the DNA template is recruited into the transcription factory, and that the nascent transcripts are accumulated in the vicinity (Iborra, et al. 1996; Jackson, et al. 1993; Jackson, et al. 1998; Pombo, et al. 2000). Our microscopic imaging and proximity analysis of RS chromatin domains, TS and pol II supports this view of transcription factories. We measured a very high degree of proximity of both TS and RS to pol II sites (> 90% TS/RS centroids ≤ 0.5 μ) (Fig. 4) with an identical level of proximity of early RS labeled chromatin domains to pol II. This is consistent with some of the pol II sites functioning as transcription factories and positioned between the chromatin domains (RS) and the transcribed products (TS) (Fig. 8C). Moreover, our cytofuorogram and CCF analysis demonstrates a high degree of co-localization of both TS and the early S replicated chromatin domains with pol II despite the very limited visible yellow color when images of these two sets of sites are merged. Virtually identical results were previously reported by Grande et al (1997) and point to the vast limitations and potential misinterpretations that can occur when using yellow color of merged raw images as a means of evaluating co-localization.

Although a previous report did not show a high degree of spatial correlation of general transcription factor sites with TS or pol II sites (Grande, et al. 1997), other studies have demonstrated targeting of specific transcription factors to the gene loci that they regulate. Examples of such targeting include the heterodimer of ARNT/HIF-1β (Elbi, et al. 2002) and the RUNX family of transcription factors (RUNX1/AML1, RUNX2/CBFA) (Harrington, et al. 2002). It is also known that while exhibiting dynamic properties, several transcription factors are targeted to the nuclear matrix and sites of pol II and RNA synthesis (Harrington, et al. 2002; He and Davie 2006; He, et al. 2005). It is speculated that specific targeting of factors to sites of gene expression and regulation in the nucleus, creates favorable nuclear microenvironments that further push the enzymatic reactions mediated by these macromolecular complex assemblies in a forward direction (Lian, et al. 2006; Saltman, et al. 2005; Stein, et al. 2005; Stein, et al. 2007; Zaidi, et al. 2006; Zaidi, et al. 2005; Zaidi, et al. 2007).

Supplementary Material

Fluoresbrite beads of 0.5 micron diameter, which could fluoresce in both red and green colors were imaged and analyzed with our segmentation and proximity programs. Besides the sub-pixel error associated with CCD imaging, ~85% of the beads were at a distance of 1 pixel to their nearest neighbor. Below is the proximity plot which describes their spatial association.

Comparison of the staining patterns produced by B3 (green, specific for hyperphosphorylated form of the RNA polymerase II large subunit) and ARNA3 (red, specific for total RNA polymerase II large subunit) antibodies. Line profile analysis of the merged image and two enlarged portions A and B, indicates the overlap between the stained patterns in red and green channels.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Daniela S. Dimitrova who first demonstrated in our laboratory the lack of co-localization between replication and transcription sites using standard epifluorescence microscopy. The authors thank Dr. George Mayers and Dr. Richard B. Bankert (University at Buffalo, NY) for providing anti-BrdU mouse monoclonal antibodies. These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM 072131 awarded to R.B.

References

- Albiez H, Cremer M, Tiberi C, Vecchio L, Schermelleh L, Dittrich S, Kupper K, Joffe B, Thormeyer T, von Hase J, Yang S, Rohr K, Leonhardt H, Solovei I, Cremer C, Fakan S, Cremer T. Chromatin domains and the interchromatin compartment form structurally defined and functionally interacting nuclear networks. Chromosome Res. 2006;14:707–733. doi: 10.1007/s10577-006-1086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber CB, Dobkin DP, Huhdanpaa HT. The Quikhull algorithm for convex hulls. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 1996;22:469–483. [Google Scholar]

- Berezney R. Regulating the mammalian genome: the role of nuclear architecture. Advances in enzyme regulation. 2002;42:39–52. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(01)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezney R, Dubey DD, Huberman JA. Heterogeneity of eukaryotic replicons, replicon clusters, and replication foci. Chromosoma. 2000;108:471–484. doi: 10.1007/s004120050399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezney R, Malyavantham KS, Pliss A, Bhattacharya S, Acharya R. Spatio-temporal dynamics of genomic organization and function in the mammalian cell nucleus. Advances in enzyme regulation. 2005;45:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezney R, Mortillaro MJ, Ma H, Wei X, Samarabandu J. The nuclear matrix: a structural milieu for genomic function. International review of cytology. 1995;162A:1–65. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezney R, Wei X. The new paradigm: integrating genomic function and nuclear architecture. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 1998;30–31:238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Acharya R, Pliss A, Malyavantham KS, Berezney R. Automated matching of genomic structures in microscopic images of living cells using an information theoretic approach. IEEE Annual International Conference of the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2005. pp. 1971–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickmore WA, Mahy NL, Chambeyron S. Do higher-order chromatin structure and nuclear reorganization play a role in regulating Hox gene expression during development? Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 2004;69:251–257. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2004.69.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, Hendzel MJ, Bazett-Jones DP. Promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies are protein structures that do not accumulate RNA. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:283–292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S, Cordelieres FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman DB, Du L, van der Zee S, Warren SL. Transcription-dependent redistribution of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II to discrete nuclear domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:287–298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakalova L, Debrand E, Mitchell JA, Osborne CS, Fraser P. Replication and transcription: shaping the landscape of the genome. Nature reviews. 2005;6:669–677. doi: 10.1038/nrg1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambeyron S, Bickmore WA. Chromatin decondensation and nuclear reorganization of the HoxB locus upon induction of transcription. Genes & development. 2004;18:1119–1130. doi: 10.1101/gad.292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambeyron S, Bickmore WA. Does looping and clustering in the nucleus regulate gene expression? Current opinion in cell biology. 2004;16:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chubb JR, Trcek T, Shenoy SM, Singer RH. Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene. Current biology. 2006;16:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cmarko D, Verschure PJ, Martin TE, Dahmus ME, Krause S, Fu XD, van Driel R, Fakan S. Ultrastructural analysis of transcription and splicing in the cell nucleus after bromo-UTP microinjection. Molecular biology of the cell. 1999;10:211–223. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook P. Duplicating a tangled genome. Science (New York, NY. 1998;281:1466–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani H, Dellaire G, Bazett-Jones DP. Organization of chromatin in the interphase mammalian cell. Micron. 2005;36:95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbi C, Misteli T, Hager GL. Recruitment of dioxin receptor to active transcription sites. Molecular biology of the cell. 2002;13:2001–2015. doi: 10.1091/mboc.13.6.mk0602002001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakan S. Inhibition of nucleolar RNP synthesis by cycloheximide as studied by high resolution radioautography. Journal of ultrastructure research. 1971;34:586–596. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(71)80065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser P. Transcriptional control thrown for a loop. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2006;16:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DM. Replication timing and transcriptional control: beyond cause and effect. Current opinion in cell biology. 2002;14:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MA, Holmquist GP, Gray MC, Caston LA, Nag A. Replication timing of genes and middle repetitive sequences. Science. 1984;224:686–692. doi: 10.1126/science.6719109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren A, Cedar H. REPLICATING BY THE CLOCK. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4:25–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande MA, van der Kraan I, de Jong L, van Driel R. Nuclear distribution of transcription factors in relation to sites of transcription and RNA polymerase II. Journal of cell science. 1997;110 (Pt 15):1781–1791. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.15.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington KS, Javed A, Drissi H, McNeil S, Lian JB, Stein JL, Van Wijnen AJ, Wang YL, Stein GS. Transcription factors RUNX1/AML1 and RUNX2/Cbfa1 dynamically associate with stationary subnuclear domains. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:4167–4176. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton KS, Dhar V, Brown EH, Iqbal MA, Stuart S, Didamo VT, Schildkraut CL. Replication program of active and inactive multigene families in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2149–2158. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Davie JR. Sp1 and Sp3 foci distribution throughout mitosis. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:1063–1070. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Sun JM, Li L, Davie JR. Differential intranuclear organization of transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3. Molecular biology of the cell. 2005;16:4073–4083. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iborra FJ, Pombo A, Jackson DA, Cook PR. Active RNA polymerases are localized within discrete transcription “factories’ in human nuclei. Journal of cell science. 1996;109 (Pt 6):1427–1436. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA, Hassan AB, Errington RJ, Cook PR. Visualization of focal sites of transcription within human nuclei. The EMBO journal. 1993;12:1059–1065. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA, Iborra FJ, Manders EM, Cook PR. Numbers and organization of RNA polymerases, nascent transcripts, and transcription units in HeLa nuclei. Molecular biology of the cell. 1998;9:1523–1536. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA, Pombo A. Replicon clusters are stable units of chromosome structure: evidence that nuclear organization contributes to the efficient activation and propagation of S phase in human cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1285–1295. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA, Pombo A, Iborra F. The balance sheet for transcription: an analysis of nuclear RNA metabolism in mammalian cells. Faseb J. 2000;14:242–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctot C, Cheutin T, Cremer M, Cavalli G, Cremer T. Dynamic genome architecture in the nuclear space: regulation of gene expression in three dimensions. Nature reviews. 2007;8:104–115. doi: 10.1038/nrg2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levsky JM, Shenoy SM, Chubb JR, Hall CB, Capodieci P, Singer RH. The spatial order of transcription in mammalian cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2007;102:609–617. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levsky JM, Shenoy SM, Pezo RC, Singer RH. Single-cell gene expression profiling. Science. 2002;297:836–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1072241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levsky JM, Singer RH. Gene expression and the myth of the average cell. Trends in cell biology. 2003;13:4–6. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian JB, Stein GS, Javed A, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Montecino M, Hassan MQ, Gaur T, Lengner CJ, Young DW. Networks and hubs for the transcriptional control of osteoblastogenesis. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2006;7:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11154-006-9001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling JQ, Li T, Hu JF, Vu TH, Chen HL, Qiu XW, Cherry AM, Hoffman AR. CTCF mediates interchromosomal colocalization between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science. 2006;312:269–272. doi: 10.1126/science.1123191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Samarabandu J, Devdhar RS, Acharya R, Cheng PC, Meng C, Berezney R. Spatial and temporal dynamics of DNA replication sites in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1415–1425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlpine DM, Rodriguez HK, Bell SP. Coordination of replication and transcription along a Drosophila chromosome. Genes & development. 2004;18:3094–3105. doi: 10.1101/gad.1246404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy NL, Perry PE, Bickmore WA. Gene density and transcription influence the localization of chromatin outside of chromosome territories detectable by FISH. The Journal of cell biology. 2002;159:753–763. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy NL, Perry PE, Gilchrist S, Baldock RA, Bickmore WA. Spatial organization of active and inactive genes and noncoding DNA within chromosome territories. The Journal of cell biology. 2002;157:579–589. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus KJ, Stephens DA, Adams NM, Islam SA, Freemont PS, Hendzel MJ. The transcriptional regulator CBP has defined spatial associations within interphase nuclei. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNairn AJ, Gilbert DM. Epigenomic replication: linking epigenetics to DNA replication. Bioessays. 2003;25:647–656. doi: 10.1002/bies.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JA, Fraser P. Transcription factories are nuclear subcompartments that remain in the absence of transcription. Genes & development. 2008;22:20–25. doi: 10.1101/gad.454008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortillaro MJ, Blencowe BJ, Wei X, Nakayasu H, Du L, Warren SL, Sharp PA, Berezney R. A hyperphosphorylated form of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II is associated with splicing complexes and the nuclear matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8253–8257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Morita T, Sato C. Structural organizations of replicon domains during DNA synthetic phase in the mammalian nucleus. Experimental cell research. 1986;165:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayasu H, Berezney R. Mapping replicational sites in the eucaryotic cell nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez E, Kwon YS, Hutt KR, Hu Q, Cardamone MD, Ohgi KA, Garcia-Bassets I, Rose DW, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD. Nuclear receptor-enhanced transcription requires motor- and LSD1-dependent gene networking in interchromatin granules. Cell. 2008;132:996–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CS, Chakalova L, Brown KE, Carter D, Horton A, Debrand E, Goyenechea B, Mitchell JA, Lopes S, Reik W, Fraser P. Active genes dynamically colocalize to shared sites of ongoing transcription. Nature genetics. 2004;36:1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/ng1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patturajan M, Schulte RJ, Sefton BM, Berezney R, Vincent M, Bensaude O, Warren SL, Corden JL. Growth-related changes in phosphorylation of yeast RNA polymerase II. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:4689–4694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombo A, Jones E, Iborra FJ, Kimura H, Sugaya K, Cook PR, Jackson DA. Specialized transcription factories within mammalian nuclei. Critical reviews in eukaryotic gene expression. 2000;10:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragoczy T, Telling A, Sawado T, Groudine M, Kosak ST. A genetic analysis of chromosome territory looping: diverse roles for distal regulatory elements. Chromosome Res. 2003;11:513–525. doi: 10.1023/a:1024939130361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Peskin CS, Tranchina D, Vargas DY, Tyagi S. Stochastic mRNA synthesis in mammalian cells. PLoS biology. 2006;4:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoni N, Cardoso MC, Stelzer EH, Leonhardt H, Zink D. Stable chromosomal units determine the spatial and temporal organization of DNA replication. Journal of cell science. 2004;117:5353–5365. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltman LH, Javed A, Ribadeneyra J, Hussain S, Young DW, Osdoby P, Amcheslavsky A, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB, Bar-Shavit Z. Organization of transcriptional regulatory machinery in osteoclast nuclei: compartmentalization of Runx1. Journal of cellular physiology. 2005;204:871–880. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarabandu J, Ma H, Acharya R, Cheng PC, Berezney R. Image analysis techniques for visualizing the spatial organization of DNA replication sites in the mammalian cell nucleus using multi-channel confocal microscopy. SPIE. 1995;2434:370–375. [Google Scholar]

- Schubeler D, Scalzo D, Kooperberg C, van Steensel B, Delrow J, Groudine M. Genome-wide DNA replication profile for Drosophila melanogaster: a link between transcription and replication timing. Nature genetics. 2002;32:438–442. doi: 10.1038/ng1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaiger M, Schubeler D. A question of timing: emerging links between transcription and replication. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2006;16:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shav-Tal Y, Darzacq X, Singer RH. Gene expression within a dynamic nuclear landscape. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:3469–3479. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparvoli E, Levi M, Rossi E. Replicon clusters may form structurally stable complexes of chromatin and chromosomes. Journal of cell science. 1994;107 (Pt 11):3097–3103. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.11.3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector DL. Macromolecular domains within the cell nucleus. Annual review of cell biology. 1993;9:265–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GS, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Javed A, Montecino M, Zaidi SK, Young DW, Choi JY, Pratap J. Combinatorial organization of the transcriptional regulatory machinery in biological control and cancer. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2005;45:136–154. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GS, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Javed A, Montecino M, Choi JY, Vradii D, Zaidi SK, Pratap J, Young D. Organization of transcriptional regulatory machinery in nuclear microenvironments: implications for biological control and cancer. Advances in enzyme regulation. 2007;47:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GS, Zaidi SK, Braastad CD, Montecino M, van Wijnen AJ, Choi JY, Stein JL, Lian JB, Javed A. Functional architecture of the nucleus: organizing the regulatory machinery for gene expression, replication and repair. Trends in cell biology. 2003;13:584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbar T, Belmont AS. Interphase movements of a DNA chromosome region modulated by VP16 transcriptional activator. Nature cell biology. 2001;3:134–139. doi: 10.1038/35055033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel B, van Binnendijk EP, Hornsby CD, van der Voort HT, Krozowski ZS, de Kloet ER, van Driel R. Partial colocalization of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors in discrete compartments in nuclei of rat hippocampus neurons. Journal of cell science. 1996;109 (Pt 4):787–792. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpi EV, Chevret E, Jones T, Vatcheva R, Williamson J, Beck S, Campbell RD, Goldsworthy M, Powis SH, Ragoussis J, Trowsdale J, Sheer D. Large-scale chromatin organization of the major histocompatibility complex and other regions of human chromosome 6 and its response to interferon in interphase nuclei. Journal of cell science. 2000;113 (Pt 9):1565–1576. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.9.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink DG, Manders EE, van der Kraan I, Aten JA, van Driel R, de Jong L. RNA polymerase II transcription is concentrated outside replication domains throughout S-phase. J Cell Sci. 1994;107 (Pt 6):1449–1456. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink DG, Schul W, van der Kraan I, van Steensel B, van Driel R, de Jong L. Fluorescent labeling of nascent RNA reveals transcription by RNA polymerase II in domains scattered throughout the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:283–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink DG, Sibon OC, Cremers FF, van Driel R, de Jong L. Ultrastructural localization of active genes in nuclei of A431 cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 1996;62:10–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(199607)62:1<10::aid-jcb2>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SL, Landolfi AS, Curtis C, Morrow JS. Cytostellin: a novel, highly conserved protein that undergoes continuous redistribution during the cell cycle. Journal of cell science. 1992;103 (Pt 2):381–388. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Samarabandu J, Devdhar RS, Siegel AJ, Acharya R, Berezney R. Segregation of transcription and replication sites into higher order domains. Science. 1998;281:1502–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Somanathan S, Samarabandu J, Berezney R. Three-dimensional visualization of transcription sites and their association with splicing factor-rich nuclear speckles. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:543–558. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AG, Fraser P. Remote control of gene transcription. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14(Spec No 1):R101–111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodfine K, Fiegler H, Beare DM, Collins JE, McCann OT, Young BD, Debernardi S, Mott R, Dunham I, Carter NP. Replication timing of the human genome. Human molecular genetics. 2004;13:191–202. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SK, Javed A, Pratap J, Schroeder TM, J JW, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein GS, Stein JL. Alterations in intranuclear localization of Runx2 affect biological activity. Journal of cellular physiology. 2006;209:935–942. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SK, Young DW, Choi JY, Pratap J, Javed A, Montecino M, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein GS. The dynamic organization of gene-regulatory machinery in nuclear microenvironments. EMBO reports. 2005;6:128–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SK, Young DW, Javed A, Pratap J, Montecino M, van Wijnen A, Lian JB, Stein JL, Stein GS. Nuclear microenvironments in biological control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:454–463. doi: 10.1038/nrc2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C, Kim E, Warren SL, Berget SM. Dynamic relocation of transcription and splicing factors dependent upon transcriptional activity. The EMBO journal. 1997;16:1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fluoresbrite beads of 0.5 micron diameter, which could fluoresce in both red and green colors were imaged and analyzed with our segmentation and proximity programs. Besides the sub-pixel error associated with CCD imaging, ~85% of the beads were at a distance of 1 pixel to their nearest neighbor. Below is the proximity plot which describes their spatial association.

Comparison of the staining patterns produced by B3 (green, specific for hyperphosphorylated form of the RNA polymerase II large subunit) and ARNA3 (red, specific for total RNA polymerase II large subunit) antibodies. Line profile analysis of the merged image and two enlarged portions A and B, indicates the overlap between the stained patterns in red and green channels.