Abstract

Magnetotactic bacteria are microorganisms that orient and migrate along magnetic field lines. The classical model of polar magnetotaxis predicts that the field-parallel migration velocity of magnetotactic bacteria increases monotonically with the strength of an applied magnetic field. We here test this model experimentally on magnetotactic coccoid bacteria that swim along helical trajectories. It turns out that the contribution of the field-parallel migration velocity decreases with increasing field strength from 0.1 to 1.5 mT. This unexpected observation can be explained and reproduced in a mathematical model under the assumption that the magnetosome chain is inclined with respect to the flagellar propulsion axis. The magnetic disadvantage, however, becomes apparent only in stronger than geomagnetic fields, which suggests that magnetotaxis is optimized under geomagnetic field conditions. It is therefore not beneficial for these bacteria to increase their intracellular magnetic dipole moment beyond the value needed to overcome Brownian motion in geomagnetic field conditions.

Introduction

Motility is an essential ability by which most bacteria can find optimal localities in their environment to maximize their substrate or energy uptake (1). Bacterial motility can be modulated via sensing energy levels within cells and of chemical signals in the environment (2). Magnetotactic bacteria, a polyphyletic group of prokaryotes that orient and swim along magnetic field lines (3), appear to have unusually high numbers of chemotaxis transducers and other proteins potentially involved in cellular signaling and bacterial taxis, which might be related to the regulation and control of magnetotaxis (4). Magnetotactic bacteria that swim parallel to the geomagnetic field in the northern hemisphere, are referred to as north-seeking; whereas, bacteria that swim anti-parallel to the geomagnetic field in the southern hemisphere are referred to as south-seeking (5,6). In aquatic habitats at the geomagnetic equator, both north-seeking and south-seeking bacteria are present in roughly equal numbers (7,8). Magnetotaxis is not independent of aerotaxis and chemotaxis, which is why it was renamed to magneto-aerotaxis or magnetically assisted aerotaxis, as the magnetic field only aligns the bacteria, whereas the oxygen-gradient finally determines the target direction of migration, toward which the bacteria then actively swim by rotating their flagella (9). It is widely believed that the function of magneto-aerotaxis is to enhance the ability of magnetotactic bacteria to sense oxygen concentration (10) and enable them to more-efficiently locate chemically favorable positions in vertically stratified environments compared to nonmagnetotactic bacteria. According to this tenet, the magnetic advantage is equivalent to a higher net migration speed, as predicted by the classical model of magnetotaxis (11), according to which VM, the migration velocity along the magnetic field lines, increases monotonically with the ambient magnetic field strength B,

| (1) |

where VF is the absolute swimming velocity of the bacterium, 〈cos θ〉 is the average alignment with θ denoting the angle between B and m (the cellular magnetic dipole moment carried by the fixed magnetosome chain), L(x) = coth(x)-1/x is the Langevin function, and kBT is the thermal energy. Equation 1 therefore expresses the balance between the aligning magnetic energy and the disorienting thermal energy. With increasing magnetic energy product mB, the average alignment of the cell body with the magnetic field lines increases, and the relative influence of the randomizing thermal energy on the bacterial motion decreases. Kalmijn (11), who derived Eq. 1 to determine the magnetic dipole moment of individual cells from their swimming tracks, found that magnetotactic bacteria in the geomagnetic field (0.05 mT) achieve 80–90% of their maximum migration speed, which itself is reached in a 0.8 mT field. Magnetotactic bacteria with coccoid cell morphology (Fig. 1) often swim along helical trajectories (Fig. 2 A). Such trajectories are due to precessional motion, which typically results from flagella that have a noninteger number of wavelengths (12,13). A noninteger number of flagellar turns implies that forces normal to the flagellum axis are not compensated, see Fig. 6.3 in Berg (14). The resulting net force produces a torque on the cell body. Since the cell body rotates, it responds to a torque by precessional motion, like a spinning top under the action of gravity. A rigorous theoretical analysis of helical swimming trajectories in magnetotactic bacteria by Nogueira and Lins de Barros (15) suggests that the precessional torque is at least one order-of-magnitude larger than the magnetic torque in ambient magnetic fields. Therefore, although we still expect the migration velocity to converge to its saturation value VF in high magnetic fields, we anticipate that much higher field values will be necessary to overcome both thermal fluctuations and precessional motion. The aim of the measurements reported below therefore is to test Eq. 1 and to explore the interplay between magnetic and precessional torques by analyzing the helical swimming trajectories of north-seeking magnetotactic coccoid bacteria over a decadal range of magnetic field values.

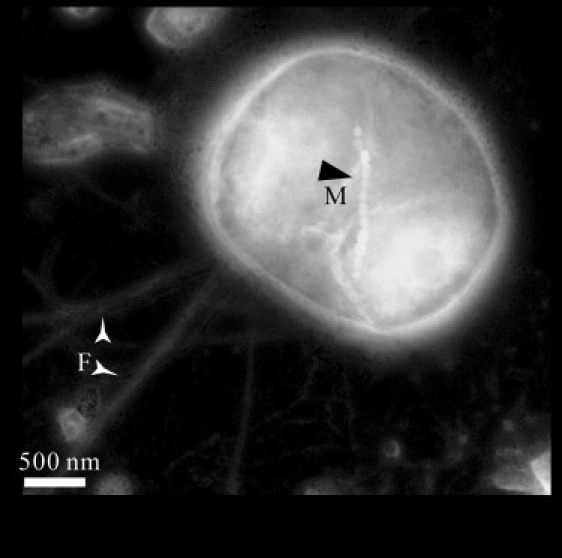

Figure 1.

Bright-field transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of a negatively stained cell of MYC-1. The image was inverted using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA). The cell contains a single chain of magnetosomes (M) and possesses two bundles of flagellae (F). Note that the linear magnetosome chain and the flagella rotating axis are not parallel.

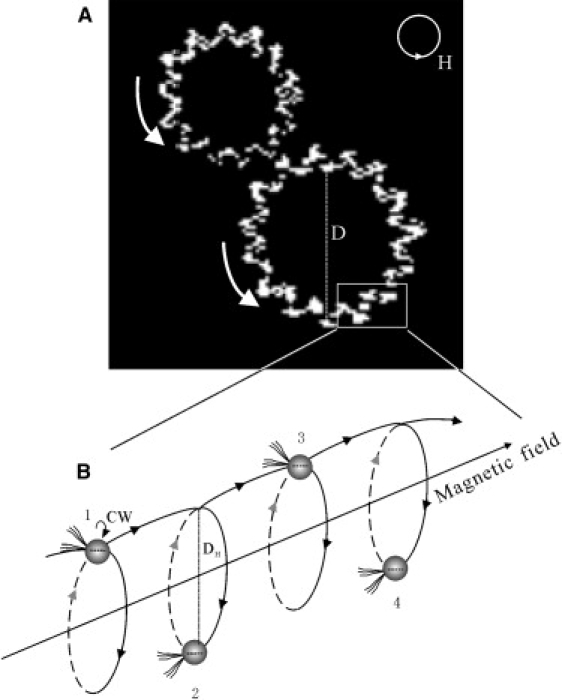

Figure 2.

(A) Observed swimming trajectories of MYC-1 in magnetic field rotating counter-clockwise in the focal plane. The helix is clearly discernable as zig-zag pattern within the focal plane. The trajectory is seemingly interrupted where the cell is above or below the focal plane. (B) Schematic drawing of helical swimming motion of a magnetic coccoid cell (CW, clockwise).

Materials and Methods

Cell samples

We used cells of an uncultivated magnetotactic coccus, which was recently enriched from Lake Miyun near Beijing, China. Lake Miyun is located in the foreland of Yanshan Mountain, ∼80 km northeast of the city of Beijing. The strength of the local geomagnetic field is ∼54,500 nT; the declination and inclination of the field are 353.5° and 59.0°, respectively. Surface sediments (5–10 cm) were collected by a shovel from the southern part (water depth ∼2–5 m) of the lake. The temperature during the collection period varied from 10 to 22°C. The pH of water collected from the lake was between 7.2 and 7.5. Sediment and water in a proportion of ∼3:1 were stored in open bottles in lab at room temperature.

To extract magnetotactic bacteria out of the sediment, a drop of sediment was put onto a clean microscope slide. Then, a drop of sterile lake water was carefully added next to the sediment, in the direction of applied field (∼0.4 mT) so as to make cells swim out of the sediment suspension toward the edge of the sterile lake water front. After a while, large quantities of cells collected at the edge of sterile lake water drop, from which they could be conveniently sucked off with a pipette for further electron-microscopic or magnetic studies (16).

TEM observations

A drop of a magnetically enriched cell-suspension was deposited onto copper grid (230 meshes) covered by a carbon-coated Formvar film. The suspension was allowed to settle on the grids for 1 h, after which time excess liquid was removed with filter paper. All grids were rinsed at least twice with sterile lake water before transmission electron microscopic (TEM) observation. For staining, a drop of negative stain (1.5% uranyl acetate solution) was applied for 1 min and blotted off. The stain was applied before the grids were completely dry. The TEM observations were conducted in a Tecnai 20 (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) with an accelerating voltage of 120 kV. Energy-dispersive x-ray analysis was performed at 300 kV on a TEM H-9000 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Bacteriodrome analysis

Swimming trajectories were observed using the so-called Bacteriodrome (17), which is a reflective light microscope devoid of magnetic parts and equipped with two sets of computer-controlled Helmholtz-coils oriented perpendicular to each other to generate a homogeneous magnetic field rotating in the horizontal plane at adjustable intensity (0.1–1.5 mT) and rotation frequency (0.1–20 Hz). Using a rotating field, cells can be forced to swim on a circular path ((17), and see our Fig. 2 B), which confines them in a small region and thus allows us to study their full trajectories at high optical resolution. The rotating field method is also highly suitable to determine magnetic properties of individual cells in the living state (18–20). An interesting modification of the rotating-field method was recently presented in Erglis et al. (21).

Analysis of swimming behavior

To study the swimming behavior, we used a rotating field of period Tc = 0.5 Hz and varied the amplitude between 0.1 and 1.5 mT. The swimming trajectories observed under the microscope were simultaneously recorded with a charge-coupled device camera (frame rate: 24 fps). The magnetotactic velocity VM was determined as VM = πD/Tc, where D was the diameter of the circular swimming path (Fig. 2 A). The rotational velocity (VR) was defined as VR = πDH/TR, where DH was the diameter of helical trajectory and TR was the period of one cycle of the trajectory (Fig. 2 B). VT was determined according to (VM2 + VR2)1/2. The pitch angle of the helix was obtained as arctan(VR/VM).

Numerical simulation of swimming trajectories

Swimming trajectories were computed according to Nogueira and Lins de Barros (15), with the important modification that the axis of the magnetic moment can be arbitrarily orientated with respect to the flagellar propulsion axis. The Euler equations and equations of motions were numerically integrated with the routine NDSolve in the Mathematica 6 (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL) routine. (The Mathematica notebook is available on request, which is to be addressed to M.W.)

Results

TEM observations showed that the magnetotactic cocci had consistent morphology and contained magnetosomes that were arranged in a single linear chain, which was oriented at an oblique angle with respect to the flagella rotational axis (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analysis of the magnetically enriched coccoid cells suggested that the cells belonged to the same population, MYC-1, and were taxonomically affiliated with the Alphaproteobacteria (22). Other morphotypes were not observed. Both energy-dispersive x-ray analysis on magnetosome crystals and low-temperature magnetic measurements of bulk cell samples demonstrated that the magnetosome crystals in MYC-1 were magnetite (Fe3O4) (23). General characteristics of MYC-1 were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics of magnetotactic coccus MYC-1

| Strain | Class. | Arrangement of flagella | Avg. cell size (μm) | No. of magnetosome chains/cell | Avg. size of magnetosomes (nm) | No. of magnetosomes per cell | Est. magnetic moment of cell (Am2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYC-1 | Alphaproteobacteria | bilophotrichous | 1.7 | 1 | 106 | 10 | 1.8 × 10−15 |

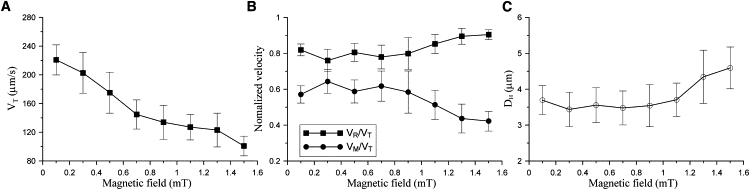

All MYC-1 cells are found to display north-seeking magnetotaxis, that is, they migrate parallel to the direction of an applied field. In a rotating magnetic field, they swim along a circular path (Fig. 2 A). Fig. 2 clearly showed a helical trajectory. The focal plane was fixed during the entire observation process; a discontinuity in the observed trajectory indicated that the cell swam out of focus plane. Fig. 3 summarized, in function of the magnetic-field strength, the analysis of the swimming velocities in terms of total speed VT, forward component VM (parallel to the magnetic field line), and rotational component VR (perpendicular to the magnetic field line), as obtained by processing several hundred video images. VT decreased in increasing magnetic fields as shown in Fig. 3 A. Since VT varied among the cells, we normalized VM and VR by the respective VT values for better comparison. An inverse correlation between VM/VT and B was apparent (Fig. 3 B). At the same time, the helix widened with increasing field strength (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

Swimming characteristics of magnetotactic coccus MYC-1 in rotating magnetic fields. (A) The total swimming velocity (VT) of MYC-1 is shown versus the magnetic field strength. (B) The variation of normalized swimming velocities, VM (parallel to the magnetic field line) and VR (perpendicular to the magnetic field line), in function of the applied magnetic field strength. (C) Helix diameter, DH (Fig. 2), as a function of field strength. All data were measured at homogeneous fields varying from 0.1 to 1.5 mT with rotating frequency of 0.5 Hz. Error bars represent the standard deviation of >60 measurements.

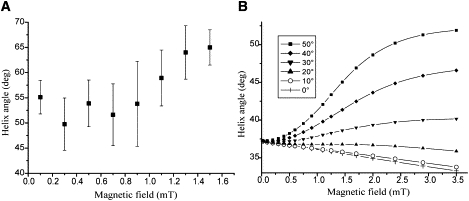

To mathematically underpin this qualitative explanation, we adopt the theoretical formalism developed in Nogueira and Lins de Barros (15), but allow for noncollinearity between the magnetosome chain and flagellar propulsion axis so that Eq. 2.14 in Nogueira and Lins de Barros (15) now reads as m = m (sin I, 0, cos I), where the inclination angle I = Ω + θ refers to the angle between magnetosome chain axis and flagellar propulsion axis (Fig. 4). The observed increase of the pitch angle of the helical trajectory with increasing magnetic field strength (Fig. 5 A) can be well reproduced with the model (ascending curves in Fig. 5 B) in case the inclination angle of the magnetosome chain is larger than the intrinsic (zero-field) pitch angle. For small inclinations (descending curves in Fig. 5 B), the pitch angle decreases, albeit at a fairly slow rate.

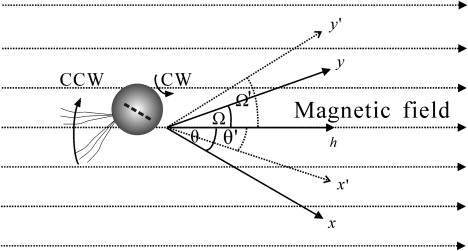

Figure 4.

Sketched mechanism of magnetic-field effect on helical motion of magnetotactic coccus MYC-1. The x and y axes are defined as a magnetosome chain axis and a flagellar propulsion axis, respectively. The position and orientation of the cell is given by the y axis and the angle θ. The broken lines represent the new x and y axes (x′, y′) after increasing the magnetic field. The h axis represents the direction parallel to the magnetic field. (CCW, counterclockwise; CW, clockwise.)

Figure 5.

(A) Observed pitch angle of helical trajectory in function of magnetic field strength, calculated from data shown in Fig. 3B. (B) Pitch angle obtained from simulated trajectories for a range of inclination angles I from 0° to 50° (inset). The magnetic-field strength has been rescaled to allow for a better comparison with experimental field values in panel A. In the simulations, the intrinsic pitch angle of the helix was set to 37°, toward which all lines converge in the limit of zero field.

Discussion

The observed inverse correlation between magnetotactic swimming velocity and the magnetic-field strength in stronger-than-geomagnetic fields is contrary to what we expected from the classical model of polar magnetotaxis (11), which predicts a positive correlation. A refined model (15) that takes into account precessional torques, which give rise to helical swimming trajectories as observed here, still predicts a positive correlation. We therefore attribute the observed magnetic-field dependence of the magnetotactic swimming velocity, and of the helix diameter, to the fact that the magnetosome chain axis is not collinear with the flagellar propulsion axis of MYC-1 (Fig. 1). The oblique orientation of the magnetosome chain produces an additional torque under a magnetic field, which causes the helical trajectory to widen. As schematically depicted in Fig. 4, neither the flagellar propulsion axis nor the magnetosomes chain is parallel to magnetic field line at any given time, since the cell body rotates as a reaction to the rotation of its flagella (conservation of angular momentum). The angles between them are denoted by Ω and θ, respectively (Fig. 4). In an increasing magnetic field (from 0.1 to 1.5 mT in this study), the angle θ decreases to θ′, because stronger external field tends to rotate the magnetosomes chain and the cell body, to which the chain is physically fixed into alignment with the field lines (24,25); consequently, the angle Ω increases toward Ω′, which subsequently causes an increase in DH and VR/VT and a decrease in VM/VT (Figs. 3 and 4).

We notice that the total velocity of the cells also tends to decrease in increasing magnetic fields (Fig. 3 A). The slowdown does not reflect physical fatigue of the cells toward the end of an experimental session with increasing field strength, because the same tendency was observed when the sequence ran from high to low field values. The slowdown in higher magnetic fields can be ascribed either to a hydrodynamic effect (higher viscous resistance) or to a reduced flagellar rotation rate. A reduced flagellar rotation rate may imply that magnetotactic cocci physiologically respond to the increasing strength of magnetic field; that is, they could sense not only the direction of the magnetic field but also its strength. Such a magnetoreceptive behavior was previously suggested by Greenberg et al. in a multicellular magnetotactic prokaryote in higher-than-geomagnetic fields (26). However, we are aware that the measured values of VR and, hence, of VT may underestimate the true values because the video/charge-coupled device camera system used in the Bacteriodrome was too slow to adequately capture the high-frequency small-amplitude helical motion (due to the noninteger number of flagellar turns). In any case, with the technique used, we are not in a position to clarify the origin of the slowdown.

It is interesting to ask the question what the magnetic advantage would be if these cocci were to raise their magnetic dipole moment from m0 to m′ by producing much more magnetosomes than needed to overcome thermal fluctuations under natural magnetic field conditions (B0), say, m0B0 ∼ 5 kBT. Since the magnetic energy –mB is the decisive magnetic quantity, that situation is by reciprocity equivalent to our experiments, in which magnetotactic bacteria with natural magnetic moments m0 were studied under much higher than natural magnetic fields B′, with m0B′ = m′B0. As we have shown, cells in which the magnetosome chains make a large angle with respect to the flagellar propulsion axis reduce their magnetotactic efficiency with increasing magnetic energy. On the other hand, cells with their magnetosome chain parallel to the flagellar propulsion axis can, in principle, enhance their magnetotactic speed. However, since the pitch angle decreases only slowly with increasing magnetic field strength (descending curves in Fig. 5 B), the cost/benefit ratio appears overproportionately high to turn this into an evolutionary advantage. We conclude that, either way, the optimal strategy for this kind of magnetotactic bacteria is to produce just enough magnetic material to surmount Brownian motion.

The advantage of helical over straight trajectories of magnetotactic cocci is not entirely clear. From the physiological point of view, the helical motion appears to be disadvantageous, since a significant fraction of the propulsion power is consumed by radial motion. However, if helical motion were a serious disadvantage, then magnetic cocci, by way of natural selection, would produce flagellae with (quasi) integer number of turns. An advantage of the helical motion may be to increase the effective feeding cross section of the cell. This benefit may partly explain the wide-spread appearance of helical motion in most known magnetotactic cocci in natural environments (15,27).

To summarize, we have shown that the classical model of polar magnetotaxis (11) requires an extension for the general case of magnetotactic bacteria whose magnetic moment is not collinear with the flagellar propulsion axis. In a field much stronger than the Earth's magnetic field, the efficiency of magnetotaxis is reduced compared to the geomagnetic field conditions, for which magnetotaxis has been evolutionarily optimized.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dirk Schüler, Ramon Egli, Xiaoya Zhan, Rui Ni, and Huafeng Qin for useful discussions. We thank Alexander Mogilner, Henrique Lins de Barros, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences project, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 40821091), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant No.Wi-1828/4-1).

Contributor Information

Yongxin Pan, Email: yxpan@mail.iggcas.ac.cn.

Michael Winklhofer, Email: michael@geophysik.uni-muenchen.de.

References

- 1.Thar R., Kühl M. Bacteria are not too small for spatial sensing of chemical gradients: an experimental evidence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5748–5753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030795100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell J.G., Kogure K. Bacterial motility: links to the environment and a driving force for microbial physics. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006;55:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faivre D., Schüler D. Magnetotactic bacteria and magnetosomes. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:4875–4898. doi: 10.1021/cr078258w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schüler D. Genetics and cell biology of magnetosome formation in magnetotactic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008;32:654–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirschvink J.L. South-seeking magnetic bacteria. J. Exp. Biol. 1980;86:345–347. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakemore R.P., Frankel R.B., Kalmijn A.J. South-seeking magnetotactic bacteria in the southern-hemisphere. Nature. 1980;286:384–385. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel R.B., Blakemore R.P., Dearaujo F.F.T., Esquivel D.M.S., Danon J. Magnetotactic bacteria at the geomagnetic equator. Science. 1981;212:1269–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.212.4500.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dearaujo F.F.T., Germano F.A., Goncalves L.L., Pires M.A., Frankel R.B. Magnetic polarity fractions in magnetotactic bacterial-populations near the geomagnetic equator. Biophys. J. 1990;58:549–555. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82398-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankel R.B., Bazylinski D.A., Johnson M.S., Taylor B.L. Magneto-aerotaxis in marine coccoid bacteria. Biophys. J. 1997;73:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78132-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith M.J., Sheehan P.E., Perry L.L., O'Connor K., Csonka L.N. Quantifying the magnetic advantage in magnetotaxis. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1098–1107. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalmijn A.J. Biophysics of geomagnetic field detection. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1981;17:1113–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe G., Meister M., Berg H.C. Rapid rotation of flagellar bundles in swimming bacteria. Nature. 1987;325:637–640. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chemla Y.R., Grossman H.L., Lee T.S., Clarke J., Adamkiewicz M. A new study of bacterial motion: superconducting quantum interference device microscopy of magnetotactic bacteria. Biophys. J. 1999;76:3323–3330. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg H.C. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1993. Random Walks in Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nogueira F.S., Lins de Barros H.G.P. Study of the motion of magnetotactic bacteria. Eur. Biophys. J. Biophys. Lett. 1995;24:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan Y., Petersen N., Winklhofer M., Davila A., Liu Q. Rock magnetic properties of uncultured magnetotactic bacteria. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005;237:311–325. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen N., Weiss D.G., Vali H. Magnetic bacteria in lake sediments. In: Lowes F., editor. Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism. NATO ASI Series C. Kluwer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberger B., Petersen N., Petermann H., Weiss D.G. Movement of magnetic bacteria in time-varying magnetic-fields. J. Fluid Mech. 1994;273:189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winklhofer M., Abracado L.G., Davila A.F., Keim C.N., Lins de Barros H.G.P. Magnetic optimization in a multicellular magnetotactic organism. Biophys. J. 2007;92:661–670. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanzlik M., Winklhofer M., Petersen N. Pulsed-field-remanence measurements on individual magnetotactic bacteria. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2002;248:258–267. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erglis K., Wen Q., Ose V., Zeltins A., Sharipo A. Dynamics of magnetotactic bacteria in a rotating magnetic field. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1402–1412. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.107474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin W., Tian L., Li J., Pan Y. Does capillary racetrack-based enrichment reflect the diversity of uncultivated magnetotactic cocci in environmental samples? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;279:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan Y., Lin W., Tian L., Petersen N., Zhu R. Combined approaches for characterization of an uncultivated magnetotactic coccus from the Lake Miyun near Beijing. Geomicrobiol. J. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheffel A., Gruska M., Faivre D., Linaroudis A., Plitzko J.M. An acidic protein aligns magnetosomes along a filamentous structure in magnetotactic bacteria. Nature. 2006;440:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature04382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komeili A., Li Z., Newman D.K., Jensen G.J. Magnetosomes are cell membrane invaginations organized by the actin-like protein MamK. Science. 2006;311:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1123231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg M., Canter K., Mahler I., Tornheim A. Observation of magnetoreceptive behavior in a multicellular magnetotactic prokaryote in higher than geomagnetic fields. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1496–1499. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefèvre C.T., Bernadac A., Yu-Zhang K., Pradel N., Wu L. Isolation and characterization of a magnetotactic bacteria from the Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]