Abstract

The homeostasis of circulating B cell subsets in the peripheral blood of healthy adults is well regulated, but in disease it can be severely disturbed. Thus, a subgroup of patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) presents with an extraordinary expansion of an unusual B cell population characterized by the low expression of CD21. CD21low B cells are polyclonal, unmutated IgM+IgD+ B cells but carry a highly distinct gene expression profile which differs from conventional naïve B cells. Interestingly, while clearly not representing a memory population, they do share several features with the recently defined memory-like tissue, Fc receptor-like 4 positive B cell population in the tonsils of healthy donors. CD21low B cells show signs of previous activation and proliferation in vivo, while exhibiting defective calcium signaling and poor proliferation in response to B cell receptor stimulation. CD21low B cells express decreased amounts of homeostatic but increased levels of inflammatory chemokine receptors. This might explain their preferential homing to peripheral tissues like the bronchoalveolar space of CVID or the synovium of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Therefore, as a result of the close resemblance to the gene expression profile, phenotype, function and preferential tissue homing of murine B1 B cells, we suggest that CD21low B cells represent a human innate-like B cell population.

Keywords: B cell differentiation, CVID

Only certain subsets of B cells can be found in the peripheral blood of healthy human adults. Usually, between 50−80% of the circulating B cells belong to the CD27 negative pool, including naïve B cells and up to 4% transitional B cells. The remaining B cells comprise CD27+IgM+IgD+ marginal zone (MZ)-like B cells, very few CD27+ IgM+IgD− (“IgM-only”) B cells, and CD27+IgM−IgD− class switched memory B cells (1). This peripheral B cell homeostasis is severely disturbed in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) (2–4). Flow cytometric analysis identified the expansion of an unusual B cell subset in CVID patients characterized by its very low expression of CD21 (complement receptor 2, CR2) (5). Since it was difficult to assign this unusual population to a known stage of B cell differentiation, we designated them as CD21low B cells (5). CD21low B cells are surface IgM positive, express elevated levels of CD19 (5), low levels of CD38 (3), chemokine receptors CXCR5 and CCR7, and no CD23 (6); this marker profile clearly discriminates them from other B cell subpopulations. The expansion of CD21low B cells correlates well with the presence of splenomegaly and granulomatous disease in CVID (2). In addition, expanded numbers of CD21low B cells have been found in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (7) and in viremic HIV patients but not in HIV patients without viremia (8).

So far, the origin and role of these B cells has remained elusive. A new facet was added to the context when CD21low B cells in HIV patients were identified as an Fc receptor-like 4 (FCRL4+) dysfunctional memory B cell population (9). Originally, FCRL4, also named immunoreceptor superfamily translocation-associated 1 (IRTA1) was identified as a marker for a CD27 positive (10) or negative (11) memory B cell population in the human tonsil. This B cell subset was assigned to the memory fraction because it lacks IgD and CD38 expression, has a high proportion of class switched B cells and an increase in somatic hypermutation (11). It consists of large lymphocytes expressing increased levels of activation markers CD69, CD80, and CD86. Recently, Ehrhardt et al. (12) found by microarray analysis a distinct gene expression profile in FCRL4+ B cells compared to conventional memory B cells.

Here we report the extended phenotype, function and gene expression profile of CD21low B cells in patients with CVID revealing a resemblance to innate-like B cells in mice.

Results

Phenotypic Characterization of CD21low B Cells Reveals a Distinct IgM+IgD+ Activated B Cell Subset.

The relative expansion of CD21low B cells above 20% of the total B cell count has been used in the Freiburg classification to classify CVID patients as type Ia (2). The analysis of 81 CVID patients (supporting information (SI) Table S1) of the Freiburg cohort showed an increase of CD21low B cells both percentage-wise and in absolute numbers in CVID Ia patients compared to non-Ia patients and healthy donors (HD) (30 ± 30 cells/μl vs. 4 ± 4 cells/μl, P = 0.0004).

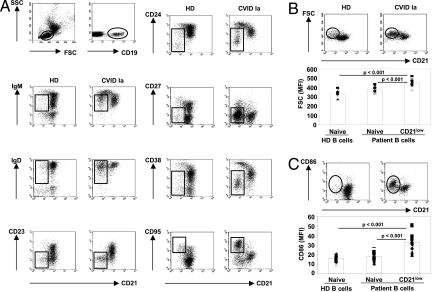

To more precisely define the phenotype of this expanded population, CD21low B cells were screened by flow cytometry for characteristic surface markers allowing a comparison with naïve B cells of the same patient and of HD. Naive B cells are characterized by the expression of CD19, CD21, CD23; intermediate levels of IgM, IgD, CD38, and CD24; but no CD27. In contrast, CD21low B cells express higher levels of CD19 and IgM; lower levels of CD21, CD38, and CD24; no CD23; low levels of CD27; and the highest levels of CD95 of all circulating B cells (Fig. 1A). Thus, these cells are clearly distinct from other circulating B cell populations, such as CD19+CD21intCD23−/loCD24hiCD27−CD38hiIgMhiIgD+ transitional B cells, CD19+CD21+CD23−CD24+CD27+CD38+/−IgM+IgD+ MZ-like B cells, CD19+CD21+CD23−CD24+CD27+CD38+/−IgM−IgD−IgA+ or IgG+ class-switched memory B cells, and CD19lowCD21lowCD23−CD24−CD27hiCD38+++IgM−/low plasmablasts. Analysis of CD21low B cells for signs of recent activation in vivo demonstrated a bigger size (FCS mean MFI 452.3 ± 36.4, n = 16) and an increased expression of CD86 (mean MFI 33.9 ± 8.9, n = 17) compared to naïve B cells of the same patient (FSC mean MFI 378.0 ± 32.9, n = 16, P < 0.001; CD86 mean MFI 18.9 ± 4.3, n = 17, P < 0.001) and HD controls (FSC mean MFI 339.9 ± 34.7, n = 10, P < 0.001; CD86 mean MFI 17.7 ± 3.0, n = 11, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1 B and C, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Phenotype of CD21low B cells. PBMCs of healthy donors and CVID Ia patients were analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) The expression of the indicated cell surface markers was analyzed on CD21+ and CD21low B cell subpopulations. CD21low B cells are indicated by rectangles. Representative profiles are shown. (B) Representative FACS plots and histograms demonstrate increased cell size according to forward scatter (FSC) as well as (C) elevated expression of CD86 of CD21low B cells. In the diagrams individual MFI values (dots), mean values (columns), and corresponding p-values (t test) of FSC and CD86 expression of HD naïve, CVID naïve and CD21low B cell subpopulations are given.

CD21low B Cells in CVID Are Polyclonal and Unmutated.

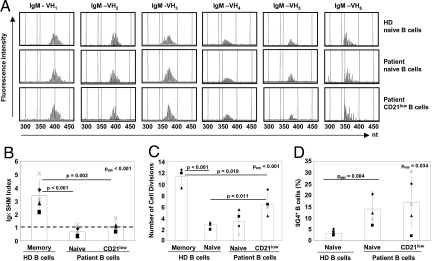

The activated phenotype and the increase of circulating CD21low B cells possibly imply an antigen driven oligoclonal expansion of this population. To test this hypothesis, we examined the expressed IgM Vh1 through Vh6 variable region genes from sorted CD21low B cells of 8 CVID Ia patients by spectratyping. The comparison with CD19+CD21+CD27− naïve B cells from the same patient and 4 HD controls demonstrated that CD21low B cells represent a subset of polyclonal B cells, indistinguishable from naïve B cells of the same patient or HD controls (Fig. 2A). In addition, we analyzed the presence of somatic hypermutations (SHM) as a sign for antigen driven selection by Igκ-REHMA assays on the transcript and genomic level [Vk A27 (13) and Vk3–20 (14)] (Fig. 2B and data not shown). There was no difference in frequency of SHM between naive and CD21low B cells of patients and HD, while memory B cells of HD consistently showed an increased SHM rate (Fig. 2B). In addition, nucleotide sequences of VH gene segments from 62 clones of naïve B cells and 49 clones from CD21low B cells of 2 CVID Ia patients as well as 19 clones of naive B cells from HD were analyzed for Vh usage, VDJ recombination and SHM. This analysis revealed similar length of CDR3 regions in VH gene segments and Vh-D and D-Jh junctions, suggesting comparable previous TdT and exonuclease activities between circulating CD21low and naive B cells of patients and HD (Table S2). The low mutation frequency in the analyzed sequences of CD21low B cells is indistinguishable from the clones derived from naïve B cells and therefore supports the findings of the Igκ-REHMA assay. Irrespective of the unmutated naïve phenotype, but compatible with the preactivated status, the analysis of kappa recombination excision circles (KREC) (14) revealed a more extensive proliferative history of CD21low B cells compared to naïve B cells of patients and HD (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the frequency of autoreactive B cells recognized by the 9G4 anti-idiotypic antibody was significantly enhanced in CVID patients with expanded circulating CD21low B cells (Fig. 2D). 9G4 positive B cells were, however, not restricted to the CD21low B cell subset, thus this expansion rather implies a generally disturbed selection process in CVID Ia patients.

Fig. 2.

CD21low B cells of CVID are polyclonal, unmutated B cells with an increased replication history and autoreactive specificity. (A) Sorted naïve B cells of 4 HD and 8 CVID patients as well as CD21low B cells of 8 CVID patients were spectratyped for the expression of Vh1 through Vh6 regions of IgM. Representative plots for each Vh gene family show the typical Gaussian distribution of polyclonal cells. (B) SHM rates in Vk A27 transcript were determined by Igκ-REHMA assay in sorted HD naive and memory as well as CVID naive and CD21low B cells (n = 5 CVID Ia patients, n = 5 HD). Individual Igκ SHM indices were calculated as the ratio of the SHM rate in the sample against the mean baseline rate of SHM in HD naive B cells. The plot indicates individual values (dots) and mean values (columns) of Igκ SHM index. (C) Replication history of CD21low B cells was assessed by KREC assay. The plot indicates individual values (dots) and mean values (columns) of numbers of cell divisions of sorted B cell subpopulations (4 HD and 4 CVID samples). (D) B cells of 6 HD and 5 CVID Ia patients were stained with the anti-idiotypic antibody 9G4. The plot indicates individual values (dots) and mean values (columns) of the percentage of 9G4 positive B cells. Kruskal-Wallis (pKW), Mann-Whitney (pMW), and t test p-values are indicated.

CD21low B Cells Reveal Defects in B Cell Receptor (BCR)-Mediated Calcium Influx and Proliferation but Produce Higher Amounts of IgM Antibody.

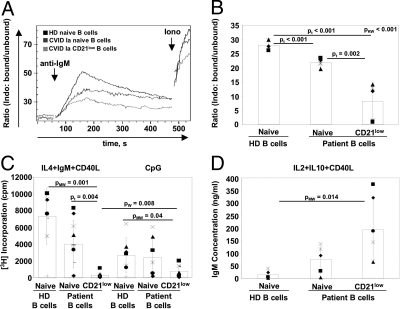

To test the functional capacity of CD21low B cells reflected by early and late events after BCR stimulation we analyzed calcium flux, proliferation and antibody production in vitro. CD21low B cells from CVID patients exhibited significantly decreased calcium influx after BCR stimulation compared to naïve B cells from CVID patients or HD (Fig. 3 A and B). The reduced calcium response after BCR stimulation in CD21low B cells was associated with a severely reduced BCR-mediated proliferative response, which could not be enhanced by anti-CD40 stimulation (Fig. 3C). In addition, CD21low B cells more frequently underwent apoptosis than naïve cells (Fig. S1). TLR9 stimulation also induced subnormal but detectable proliferation of CD21low B cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, CD21low B cells produced significantly more IgM than naïve B cells of HD after stimulation with CD40L, IL2, and IL10 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Altered response of CD21low B cells to B cell receptor stimulation. (A) The increase in intracellular calcium concentration in B lymphocytes upon BCR stimulation was measured. An overlay of representative plots for a CVID Ia patient and a HD control is shown. Time points of adding the respective stimulus are indicated. (B) The plot demonstrates individual values (dots) and mean values (columns) of maximum fluorescence ratio after IgM stimulation of B cell subpopulations of 5 HD and 5 CVID samples. (C) Proliferative responses of sorted B cells were evaluated by 3H Thymidin incorporation on day 3 and (D) IgM production in supernatants after 7 days of stimulation as indicated. Plots depict individual values (dots) and mean values (columns). P-values according to Kruskal-Wallis (pKW), Mann-Whitney (pMW), Wilcoxon (pW), and t tests (pt) are indicated.

Gene Expression Profiles of CD21low B Cells in CVID Patients.

Comparison of gene expression profiles of sorted CD19+CD27−CD38−/lowCD21low B cells of 4 CVID patients, CD19+CD27−CD38+CD21+ naïve B cells of the same patients and of 4 HD identified 321 probe sets for known functionally annotated genes, unknown expressed sequence tags (ESTs), or gene sequences for hypothetical proteins, which are at least 3-fold up- or down-regulated when comparing CD21low B cells from CVID patients with naïve B cells from HD (316 genes) or CVID patients (21 genes) (P value of P < 0.01 and false discovery rate (FDR) of 2.2%). The previously identified deregulation of CD19, CD21, CD23, CD38, CD86, and CD95 was reproduced at the transcriptional level (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2).

The transcription factor sex determining region Y (SRY)-box 5 (SOX5) stood out as one of the highest up-regulated genes in CD21low B cells. qRT-PCR confirmed a 10-fold up-regulation compared to naïve B cells of HD and over 2-fold up-regulation compared to naive B cells of CVID patients (Fig. S3A). Noteworthy, SOX5 had also been identified as one of the differentially regulated genes in FCRL4+ B cells (12). We therefore compared the expression of other markers characterizing FCRL4+ B cells. CVID derived CD21low B cells express increased levels of FCRL4 transcript (Fig. S3A) and protein (Fig. S3B) and share the reported phenotype with regard to CD20, CD62L, and CD11c expression (Fig. S3B) (12). Also, several transcripts of other FCRL family members (15), like FCRL2, FCRL3, FCRL5, FCRLM1, and FCRLM2 were up-regulated (Fig. S2).

CD21low B Cells Express Inflammatory Chemokine Receptors and Constitute the Main B-Cell Population in Peripheral Tissue Like the Bronchoalveolar Space.

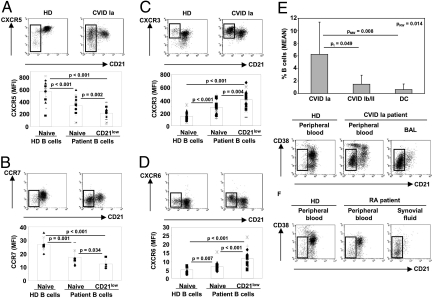

Usually, the homeostatic chemokine receptors CXCR5 and CCR7 are highly expressed on all circulating B cell populations and allow homing to B cell and T cell zones of secondary lymphoid tissues, respectively (16, 17). CD21low B cells express variable, mostly decreased levels of CXCR5 (mean MFI 229.7 ± 99.9, n = 17) compared to naïve B cells of the same patient (mean MFI 356.6 ± 121.4, n = 17, P = 0.002) and to naïve B cells of HD (mean MFI 591.1 ± 159.2, n = 16, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). A significant proportion of CD21low B cells (34.0% ± 13.9%, n = 16) has even lost the surface expression of CXCR5 completely. CCR7 expression is also consistently decreased on naive B cells (mean MFI 17.5 ± 5.6, n = 9) and even more so on CD21low B cells of CVID Ia patients (mean MFI 12.3 ± 3.1, n = 9, P = 0.034) in comparison to B cells of HD (mean MFI 26.9 ± 4.7, n = 9, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the expression of inflammatory type chemokine receptors CXCR3 (Fig. 4C) and CXCR6 (Fig. 4D) (CXCR3: mean MFI 454.0 ± 123.3, n = 15; CXCR6: 12.2 ± 4.4, n = 19) are up-regulated in CD21low B cells compared to naïve B cells of the same patient (CXCR3: mean MFI 323.5 ± 106.3, n = 15, P = 0.004; CXCR6: 7.3 ± 2.3, n = 19, P < 0.001) and of HD (CXCR3: mean MFI 143.5 ± 66.8, n = 13, P < 0.001; CXCR6: 5.2 ± 1.8, n = 11, P < 0.001). The altered expression of CXCR5 and CCR7 on CD21low B cells of CVID patients, which had also been described by others (6), in combination with the increased expression of inflammatory chemokine receptors points to the potential of CD21low B cells to migrate into inflammatory sites. So we examined bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids of 8 CVID Ia patients with interstitial lung disease but no signs of a concurrent bacterial respiratory infection for the presence of CD21low B cells (Fig. 4E and Fig. S4A). While the absolute cell and lymphocyte counts in BAL fluid did not differ significantly between the groups, the lavage of 10 disease controls (DC) and 6 CVID non-Ia patients contained only very few B cells (0.6% ± 0.9% and 1.5% ± 1.4%, respectively) in contrast to 6.2% ± 5.1% of BAL lymphocytes in CVID Ia patients (P = 0.014). Further characterization demonstrated that CD21low B cells are the dominant B cell population in the BAL of all analyzed patients (74.9% ± 26.5%, n = 14; 10 patients had too low B cell numbers for analysis) and especially CVID Ia patients (88.4% ± 6.3%). In contrast, this population was rare (mean 7.2% ± 0.7%, n = 3) in 3 lymph nodes of CVID Ia patients. The phenotype of BAL derived CD21low B cells closely resembled that of circulating CD21low B cells (Fig. S4B). In addition, we found CD21low B cells to be the major B cell population in the synovial fluid from patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 4F) as it had been previously suggested by data of Illges et al. (18). Thus, CD21low B cells represent a tissue homing subset of B cells, which is most likely expanded by inflammatory stimuli in various diseases but also present in low numbers in healthy individuals.

Fig. 4.

Chemokine receptor expression and enrichment of CD21low B cells in the bronchoalveolar space. After gating on CD19+ cells, CD21+ and CD21low B cells were analyzed for the expression of CXCR5 (A), CCR7 (B), CXCR3 (C) and CXCR6 (D). Representative flow cytometric profiles of B lymphocytes of HD and CVID Ia patients are shown. Plots indicate individual MFI values (dots) of each chemokine receptor, mean values (columns) for HD naïve, CVID naïve, and CD21low B cell subpopulations. P-values are calculated according to the Mann-Whitney-test. (E) CD19+ B cells were determined in the BAL of 8 CVID type Ia patients, 6 control CVID (Ib and II) patients and 10 disease control (DC) patients. Columns indicate mean percentage (± SD) and p-values of Kruskal-Wallis (pKW), Mann-Whitney (pMW) and t tests (pt) are depicted. (F) Flow cytometric analysis shows that CD21low B cells (open rectangles) are the main B lymphocyte population in the synovial fluid of active rheumatoid arthritis patients. A representative example is shown.

CD21low B Cells Resemble Innate-Like B Cells in Humans.

To identify the origin and role of CD21low B cells, we compared their identified phenotypic, transcriptional, and functional profile to currently known information on B cell populations in mice and humans. As mentioned above, there is a remarkable resemblance with the FCRL4+ B cell population in the tonsil (11), but CD21low B cells in CVID do not represent a memory population in that they are lacking class switch, SHM, and oligoclonality. The homing of CD21low B cells to peripheral tissue is reminiscent of B1 B cells in mice. The comparison of B1 B cells and CD21low B cells demonstrates a common phenotype regarding the expression of CD19, CD21, CD22, CD23, CD86, CD95, and IgM [Fig. S5 and (19)]. Table S3 summarizes the strong phenotypic and functional resemblance of both populations. Unfortunately, only few data on the gene expression signature of mouse B1 cells are available. The comparison of 15 differentially regulated genes reported by Yamagata T et al. (20) for B1 B cells demonstrates a significant concordance of 8 and in one patient even 11 genes in CD21low B cells, while none of the examined genes resembled the profile of naïve cells. Based on the enrichment in peripheral tissues and the great similarity to B1 B cells we suggest an innate-like origin of CD21low B cells.

Discussion

We and others have described the unusual expansion of CD21low B cells in the peripheral blood of patients with CVID (2), viremic HIV infection (8) and systemic lupus erythematosus (7). This population is clearly distinct from all other circulating B cell populations. The low expression of CD38 distinguishes these cells from both other CD21 low-expressing B cell populations and transitional B cells, as well as plasmablasts (3). While also being different from conventional naïve B cells by phenotype and gene expression profile, the surface expression of IgM and IgD, lack of class switched isotypes, and the low CD27 expression are compatible with a naïve-like status of most CD21low B cells in CVID. This is corroborated by the polyclonality and the lack of somatic hypermutation of this population excluding an antigen driven origin, especially a germinal center derived memory stage. The up-regulation of CD86 and the increased cell size indicate recent activation, while the high surface expression of IgM and IgD argue against an activation involving the B cell receptor. In several CVID patients with expanded circulating CD21low B cells, we had the chance to analyze B cells in lymph node, spleen, and bronchoalveolar lavage. While lymph nodes and spleens contained less CD21low B cells than the peripheral blood, we found CD21low B cells to present the predominant B cell population in the bronchoalveolar space. These cells resemble closely their circulating counterparts. Interestingly, this local dominance of CD21low B cells was independent of the underlying disease. Also in synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a peripheral inflammatory tissue with known B cell infiltration (21), most B cells were CD21low B cells closely resembling CD21low B cells in BAL and peripheral blood of CVID patients supporting the notion that CD21low B cells are enriched in peripheral tissues.

Their homing to peripheral tissue is highly reminiscent of the nature of innate B cells in mice (22). B1 B cells designate a specialized innate B cell population distinct from conventional B2 cells, including follicular (FO) B cells as well as MZ-B cells, by their origin, unique tissue distribution, polyreactive antigen specificity, and capacity of self renewal (19). Comparison of CD21low B cells of CVID patients with conventional B2 and B1 B cells demonstrated a similar, partially activated phenotype, with the exception of the expression of CD5, CD38, and CD24, which seem to be differentially regulated in humans and mice (22–25). In human peripheral blood, CD5 is expressed on the majority of transitional B cells and some CD21low and naïve B cells, thus rendering CD5 not a marker for a specific human B cell subset. CD21low B cells and B1 B cells have a history of higher in vivo turnover than conventional naïve B2 B cells (19). Unlike B1a B cells, CD21low B cells show signs of previous TdT activity and thus don't seem to derive from a fetal liver precursor population. CD21low B cells from CVID patients are polyclonal B cells with increased poly- and even autoreactive specificities (E. Meffre, personal communication) in assays using single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning of the BCR (26). In fact, the frequency of autoreactive clones was compatible to early immature B cells (27). Polyreactivity and an increased autoreactivity is a significant trait in innate-like B cells affecting the selection into this pool (22). Finally, similar to B1 B cells and probably associated with the partially activated, polyreactive status, in vitro stimulation of the BCR causes only poor calcium influx and proliferative response in CD21low B cells and increased apoptosis, even after costimulation with CD40 (28, 29). This attenuated response might be the result of increased levels of several inhibitory receptors like CD22 (30), Siglecs (28) and FCRLs (only human) in CD21low B cells as well as B1 B cells. Also the response to CpG stimulation is reduced in CD21low B cells and murine B1 B cells compared to their respective naïve counterparts (31). On the contrary, Ig synthesis is even enhanced in CD21low B cells, suggesting a preferential differentiation into antibody secreting cells.

Partial anergy referring to a functional nonresponsiveness of mature lymphocytes seems to be a common tolerogenic trait among innate-like B cells (32). Thus, signaling in innate-like B cells resembles the signaling in classical anergy (33) as described in the soluble HEL model (34). Innate-like B cells including CD21low B cells, however, differ from the classical form of anergy in several important aspects. Anergic anti-HEL B cells require constant BCR occupancy (35) and therefore express low IgM receptors. They fail to up-regulate CD86 (36) and do not produce antibody on stimulation in vitro. Both functions are preserved in CD21low B cells and in murine innate-like B cells, rendering these cells a potential threat of autoimmunity, which in fact is increased in CVID Ia patients.

The additional resemblance of CD21low B cells with FCRL4+ B cells in human tonsils (11) is remarkable, especially in view of the presence of FCRL4+CD21low B cells in the blood of HIV (8) and SLE patients (7). The major difference between these populations is the lack of class switch, SHM and oligoclonality in CVID derived CD21low B cells, assigning them into the nonmemory pool. This difference might be due to the underlying defect in memory formation in CVID (2). Thus nonswitched and switched CD21low B cells might represent different stages of a developmental continuum. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that in the blood of HD, SLE patients (7), as well as in human tonsils (10) IgM+, unmutated, naïve-like FCRL4+CD21low B cells have been described alongside with the mutated memory-like FCRL4+CD21low B cells.

In conclusion, this study reveals that in CVID, CD21low B cells are a distinct, polyclonal, preactivated, partially autoreactive, functionally attenuated B cell population with preferential enrichment in peripheral tissues. Thus, strongly resembling murine innate-like B cells, we suggest that human CD21low B cells represent an innate-like B cell population, abnormally expanded in the peripheral blood of a subgroup of CVID patients. Further studies will be important to shed more light on the relation between nonswitched and switched FCRL4+CD21low B cells in the various disease entities and their origin and role in the human immune system. In CVID, future work needs to address the origin and effect of the dramatic expansion of circulating innate-like B cells in the context of altered B cell function and selection.

Materials and Methods

Description of Patient and Healthy Donor Cohorts.

81 CVID patients including 29 Freiburg type Ia patients (Table S1) diagnosed in line with the European Society for Immunodeficiencies criteria were classified according to the Freiburg (2) and EUROclass (3) classification. CVID patients and controls (10 DC patients and 31 HD) were between 17 and 75 years of age. BAL was performed in 8 CVID Ia and 6 CVID Ib/II, as well as 10 DC patients for medical indication. Informed written consent to the internal ethics review board-approved clinical study protocol (University Hospital Freiburg 239/99) was obtained from each individual before participation in the study, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Flow Cytometric Analysis and Cell Sorting.

Antibodies used in flow cytometry and calcium flux assay are described in SI Material and Methods. Anti-FCRL4 antibodies were a generous gift of Dr. Max Cooper (Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA). VH4–34 specific 9G4 antibodies were kindly provided by Dr. Freda Stevenson (University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom).

Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACSCaliburTM or LSR II (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc.) software. For cell sorting naïve and CD21low B cells of patients and HD, the cells were separated into CD19+CD27−CD21+CD38+ cells and CD19+CD27−CD21−CD38− cells respectively to a purity of >95% using a MoFlow cell sorter (DakoCytomation).

Microarray Analysis.

Human genome U133 plus 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix U.K. Ltd.) were used. The description of the RNA amplification and hybridization experiments is in SI Material and Methods.

Analysis of microarray data were performed using dChip software (37). Microarray data are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/geo/) under accession no. GSE17269.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

qRT-PCR for SOX5, FCRL4, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) genes was performed using a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). Primer sequences and PCR conditions are provided in SI Material and Methods.

IgH CDR3 Spectratyping and Analysis of VH Gene Repertoire.

IgH CDR3 spectratyping was performed as described by Pannetier et al. (38) for analysis of the TCRγ-chain. We used primers as established by Kueppers et al. (39). In brief, the CDR3 regions were amplified using 35 cycles of PCR with a forward primer specific for the V region family and the common reverse primer from the constant region (39). In a second round, 3 cycles of a primer extension reaction with a fluorescent (5′ FAM-labeled) nested reverse primer specific for the constant region was performed. The run-off products were then analyzed on an ABI 3100 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems) to determine the length distribution of the fluorescent fragments.

Multiplex PCR for VH-JH rearrangements was performed according to (40). Description of analysis of VH gene repertoire, B cell proliferation and Ig secretion assays are in SI Material and Methods.

SHM Analysis and KREC Assay.

SHM in the Vκ A27 transcript was analyzed using Igκ-restriction enzyme-based hot-spot mutation assay (Igκ-REHMA assay) as described by Andersen et al. (13). Igκ-REHMA assay for Vκ3–20 gene as well as KREC assay was performed as described previously (14).

Statistical Analysis.

All data are expressed as mean ± SD unless indicated otherwise. Statistical comparison between groups was carried out using paired and unpaired t tests, the Kruskal-Wallis (KW) ANOVA by ranks and in cases of significant differences, the Mann-Whitney (MW) test between groups were applied as indicated using SigmaStat 3.1 software (Systat Software GmbH).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank Dr. Jens Thiel and Dr. Manuella Gomes for patient care, Ruth Draeger, Stefanie Hahn, Sylvia Kock, Dr. Marie Follo, Klaus Geiger, Dr. Andrea Heinzmann, and Jessica Heinze for their technical support and Cornelius Struck, Dr. Michael Schlesier and Dr. Anne-Marie Eades-Perner for help in preparing the manuscript. This research was funded by the German Research Foundation grant SFB620, projects C1 (to K.W., H.H.P.), C2 (to U.S.), and Z2 (to P.F.), 7th framework programs of the European Union Grant Nr. HEALTH-F2–2008-201549 (to K.W., H.E., U.S., I.Q.) and BMBF grant CCI-01E O0803 (to K.W., H.E., U.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE17269).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0901984106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Warnatz K, Schlesier M. Flowcytometric phenotyping of common variable immunodeficiency. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2008;74:261–271. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warnatz K, et al. Severe deficiency of switched memory B cells (CD27(+)IgM(−)IgD(−)) in subgroups of patients with common variable immunodeficiency: A new approach to classify a heterogeneous disease. Blood. 2002;99:1544–1551. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wehr C, et al. The EUROclass trial: Defining subgroups in common variable immunodeficiency. Blood. 2008;111:77–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-091744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piqueras B, et al. Common variable immunodeficiency patient classification based on impaired B cell memory differentiation correlates with clinical aspects. J Clin Immunol. 2003;23:385–400. doi: 10.1023/a:1025373601374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnatz K, et al. Expansion of CD19(hi)CD21(lo/neg) B cells in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) patients with autoimmune cytopenia. Immunobiology. 2002;206:502–513. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moratto D, et al. Combined decrease of defined B and T cell subsets in a group of common variable immunodeficiency patients. Clin Immunol. 2006;121:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wehr C, et al. A new CD21low B cell population in the peripheral blood of patients with SLE. Clin Immunol. 2004;113:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moir S, et al. HIV-1 induces phenotypic and functional perturbations of B cells in chronically infected individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10362–10367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181347898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moir S, et al. Evidence for HIV-associated B cell exhaustion in a dysfunctional memory B cell compartment in HIV-infected viremic individuals. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1797–1805. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falini B, et al. Expression of the IRTA1 receptor identifies intraepithelial and subepithelial marginal zone B cells of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) Blood. 2003;102:3684–3692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrhardt GR, et al. Expression of the immunoregulatory molecule FcRH4 defines a distinctive tissue-based population of memory B cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:783–791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrhardt GR, et al. Discriminating gene expression profiles of memory B cell subpopulations. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1807–1817. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen P, et al. Deficiency of somatic hypermutation of the antibody light chain is associated with increased frequency of severe respiratory tract infection in common variable immunodeficiency. Blood. 2005;105:511–517. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Zelm MC, Szczepanski T, van der BM, van Dongen JJ. Replication history of B lymphocytes reveals homeostatic proliferation and extensive antigen-induced B cell expansion. J Exp Med. 2007;204:645–655. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehrhardt GR, et al. Fc receptor-like proteins (FCRL): Immunomodulators of B cell function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;596:155–162. doi: 10.1007/0-387-46530-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster R, et al. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forster R, et al. CCR7 coordinates the primary immune response by establishing functional microenvironments in secondary lymphoid organs. Cell. 1999;99:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Illges H, Braun M, Peter HH, Melchers I. Reduced expression of the complement receptor type 2 (CR2, CD21) by synovial fluid B and T lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:270–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fagarasan S, Watanabe N, Honjo T. Generation, expansion, migration and activation of mouse B1 cells. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:205–215. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamagata T, Benoist C, Mathis D. A shared gene-expression signature in innate-like lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:52–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HJ, Berek C. B cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:126–131. doi: 10.1186/ar77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy RR. B-1 B cell development. J Immunol. 2006;177(5):2749–2754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carsetti R, Rosado MM, Wardmann H. Peripheral development of B cells in mouse and man. Immunol Rev. 2004;197:179–191. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridderstad A, Tarlinton DM. Kinetics of establishing the memory B cell population as revealed by CD38 expression. J Immunol. 1998;160:4688–4695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YJ, Arpin C. Germinal center development. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:111–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiller T, et al. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wardemann H, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffmann A, et al. Siglec-G is a B1 cell-inhibitory receptor that controls expansion and calcium signaling of the B1 cell population. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:695–704. doi: 10.1038/ni1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erickson LD, Foy TM, Waldschmidt TJ. Murine B1 B cells require IL-5 for optimal T cell-dependent activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:1531–1539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danzer CP, Collins BE, Blixt O, Paulson JC, Nitschke L. Transitional and marginal zone B cells have a high proportion of unmasked CD22: Implications for BCR signaling. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1137–1147. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genestier L, et al. TLR agonists selectively promote terminal plasma cell differentiation of B cell subsets specialized in thymus-independent responses. J Immunol. 2007;178:7779–7786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cambier JC, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Vilen BJ. B-cell anergy: From transgenic models to naturally occurring anergic B cells? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodnow CC, Brink R, Adams E. Breakdown of self-tolerance in anergic B lymphocytes. Nature. 1991;352:532–536. doi: 10.1038/352532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong SC, et al. Peritoneal CD5+ B-1 cells have signaling properties similar to tolerant B cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30707–30715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauld SB, Benschop RJ, Merrell KT, Cambier JC. Maintenance of B cell anergy requires constant antigen receptor occupancy and signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1160–1167. doi: 10.1038/ni1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathmell JC, Fournier S, Weintraub BC, Allison JP, Goodnow CC. Repression of B7.2 on self-reactive B cells is essential to prevent proliferation and allow Fas-mediated deletion by CD4(+) T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:651–659. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: Expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pannetier C, Levraud P, Lim A, Even J, Kourilsky P. In: The Antigen T Cell Receptor: Selected Protocols and Applications. Oksenberg JR, editor. London: Chapman & Hall; 1998. pp. 287–325. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuppers R, Zhao M, Rajewsky K, Hansmann ML. Detection of clonal B cell populations in paraffin-embedded tissues by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:230–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Dongen JJ, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98–3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.