Abstract

Many human diseases are caused by dysregulated gene expression. The oversupply of transcription factors may be required for the growth and metastatic behavior of human cancers. Cell permeable small molecules that can be programmed to disrupt transcription factor-DNA interfaces could silence aberrant gene expression pathways. Pyrrole-imidazole polyamides are DNA minor-groove binding molecules that are programmable for a large repertoire of DNA motifs. A high resolution X-ray crystal structure of an 8-ring cyclic Py/Im polyamide bound to the central 6 bp of the sequence d(5′-CCAGGCCTGG-3′)2 reveals a 4 Å widening of the minor groove and compression of the major groove along with a >18 ° bend in the helix axis toward the major groove. This allosteric perturbation of the DNA helix provides a molecular basis for disruption of transcription factor-DNA interfaces by small molecules, a minimum step in chemical control of gene networks.

Keywords: DNA binders, gene regulation, minor groove binders, Py-Im polyamides, crystal structure

Py/Im polyamides bind the minor groove of DNA sequence specifically (1, 2), encoded by side-by-side arrangements of N-methylpyrrole (Py) and N-methylimidazole (Im) carboxamide monomers. Im/Py pairs distinguish G·C from C·G base pairs, whereas Py/Py pairs are degenerate for T·A and A·T (3–6). Antiparallel Py/Im strands are connected by a γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) linker to create hairpin-shaped oligomers. Hairpin Py/Im polyamides have been programmed to bind a broad library of different DNA sequences (7). They have been shown to permeate cell membranes (8–10), access chromatin (11, 12), and disrupt protein-DNA interactions (2). Disruption of transcription factor-DNA interfaces 6 bp in size such as HIF-1α (13–15), androgen receptor (AR) (16), and AP-1 (17, 18) have been exploited for controlling expression of medically relevant genes such as VEGF, PSA, TGF-β1, and LOX-1 in cell culture experiments (13–18). X-ray crystallography of antiparallel 2:1 binding polyamides in complex with DNA reveal a 1–2 Å widening of the minor groove (5, 6). This modest structural perturbation to the DNA helix by the side-by-side stacked arrangement of aromatic rings does not explain the large number of transcription factor-DNA interfaces disrupted by minor-groove binding hairpin Py/Im polyamides (2, 5, 6, 19). It must be that the turn unit in the hairpin oligomer connecting the 2 antiparallel strands plays a structural role.

NMR studies of hairpin polyamide-DNA complexes have provided valuable insight into polyamide binding site location, stoichiometry, and binding orientation (20–22). An NMR structure of a 6-ring GABA-linked cyclic polyamide has confirmed DNA binding and orientational preference. However, little difference in minor groove width compared to ideal B-form DNA is observed when measuring C1′ to C1′ distances in these models. In addition, the lack of identical DNA structures without polyamide ligand have prevented detailed structural comparisons (23). X-ray structures of hairpin polyamides bound to the nucleosome core particle (NCP) at modest resolution (>2 Å) have revealed a widening of the minor groove (average <2 Å) upon polyamide binding (24, 25).* Interestingly, large perturbations were observed distal to the polyamide binding sites in addition to long-range structural changes in the NCP. However, given the modest resolution and disorder (high B-factors) in the polyamide binding regions of the NCP-polyamide structures coupled with the perturbations induced by nucleosome bound DNA, there is a pressing need for higher resolution crystallographic studies to elucidate DNA structural distortions and molecular recognition details of polyamide-DNA binders at atomic resolution. High-resolution structural studies of polyamide-DNA complexes in the absence of nucleosome bound DNA are needed to adequately evaluate DNA perturbations induced by polyamide minor groove binding that result in the inhibition of transcription factors bound to the DNA major groove.

The DNA structural alterations imparted upon polyamide binding can be classified as direct perturbations to the polyamide minor groove binding site, proximal allosteric perturbations, and distal allosteric perturbations. Proximal allosteric perturbations occur primarily in the major groove as a result of polyamide binding to the minor groove, whereas distal allosteric perturbations occur outside of the binding site location displaced in the 3′ or 5′ direction. NCP-polyamide structures have demonstrated the possibility of distal allosteric perturbations at moderate resolution (24); however, direct perturbations and proximal allosteric DNA perturbations relevant to transcription factor inhibition have not been characterized at atomic resolution.

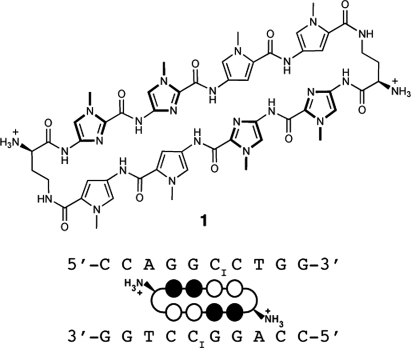

Here we report the atomic resolution structure (1.18 Å resolution) of an 8-ring cyclic polyamide in complex with double helical DNA. The cyclic polyamide 1 is comprised of two antiparallel ImImPyPy strands capped at both ends by (R)-α-amino-γ turn units. Polyamide 1, which codes for the sequence 5′-WGGCCW-3′, was co-crystallized with the palindromic DNA oligonucleotide sequence 5′-CCAGGCICTGG-3′ 10 bp in length (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1 and S2). Compared with free DNA, we observe significant structural changes of the DNA helix induced upon binding of the 8-ring cycle in the minor groove.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of the cyclic polyamide and DNA sequence. Cyclic polyamide 1 targeting the sequence 5′-WGGCCW-3′ shown with ball-and-stick model superimposed onto the DNA oligonucleotide used for crystallization. Black circles represent imidazoles, open circles represent pyrroles, and ammonium substituted half circles at each end represent the (R)-α-amine-γ-turn.

Results and Discussion

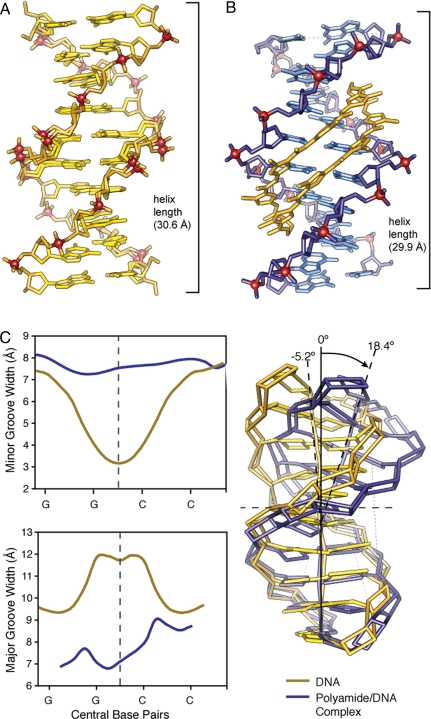

In the complex, each ImImPyPy strand is bound with N- to C- orientation aligned with the 5′ to 3′ direction of the DNA. The cyclic polyamide 1 rigidifies the sugar-phosphate backbone and strongly perturbs the overall helix structure. The cycle widens the minor groove of DNA up to 4 Å while simultaneously compressing the major groove by 4 Å. The polyamide bends the DNA helix >18° toward the major groove, and shortening the overall length by ≈1 Å. The cycle is a sequence specific allosteric modulator of DNA conformation (Fig. 2) (26).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of native DNA to polyamide/DNA complex. (A) Native DNA crystal structure at 0.98 Å resolution. (B) Comparison to DNA/polyamide co-crystal structure at 1.18 Å resolution. (Both structure solved by direct methods.) (C) Analysis of native DNA (yellow) compared to polyamide complexed DNA (blue). Chart on the top left shows variation in the minor groove width for native DNA (yellow) and polyamide-complexed DNA (blue) over the central core sequence 5′-GGCC-3′. Chart on the bottom left shows variation in the major groove width for native DNA (yellow) and polyamide complexed DNA (blue) over the central core sequence 5′-GGCC-3′. Overlay of the curves calculated geometric helix model from each structure showing a DNA bend of >18° in the polyamide/DNA complex compared to native DNA.

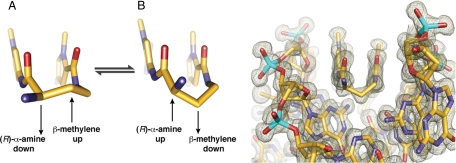

Py/Im polyamides linked by a GABA or substituted GABA can adopt either of two possible conformations on the floor of the DNA minor groove (Fig. 3). In conformation A the amino group is directed toward the minor-groove wall of the DNA helix with the potential for steric clash with the deoxyribose backbone. In alternative conformation B the amine is directed up and out of the minor groove forcing the β-methylene to the floor of the minor groove with the potential for steric interaction with the edge of the base pairs and within van der Waals contact distance of the C2 hydrogen of adenine. We observe the latter conformation B in our high resolution X-ray structure at both ends of the complex (Fig. 3). It is possible that there is an intrinsic preference for conformation A, which relieves the β-methylene interaction with the floor of the minor groove. For turn substitution at the α-position, however, interaction with the minor-groove wall becomes the dominant steric interaction, leading to conformational inversion. Fig. 3 presents a view of the complex looking down the minor groove directly at the hairpin turn unit. Significant van der Waals interactions can be observed between the outside face of the pyrrole-imidazole strands and the walls of the minor groove, which form a deep binding pocket for the cycle. Approximately 40% of the polyamide surface area is buried, leaving only the top of the methyl groups on the heterocycles, the amide carbonyl oxygens, and the chiral α-ammonium turn solvent exposed. A detailed view of the α-amino-γ-turn conformation and hydration reveal a network of well-ordered water-mediated interactions between the polyamide and the minor groove floor of DNA.

Fig. 3.

Conformation of the α-amino substituted GABA turn. Two possible Conformations A and B are shown with conformation A directing the β-methylene up and away from the minor groove floor while orienting the α-ammonium toward the minor groove wall. Conformation B presents the β-methylene down toward the minor-groove floor while orienting the α-ammonium up and out of the minor-groove, relieving possible steric interaction with the sugar-phosphate backbone (minor-groove wall). View looking down the DNA minor-groove, showing the (R)-α-amine-γ-turn conformation observed in the X-ray crystal structure, which matches that of conformation B. Electron density map is contoured at the 1.0 σ level.

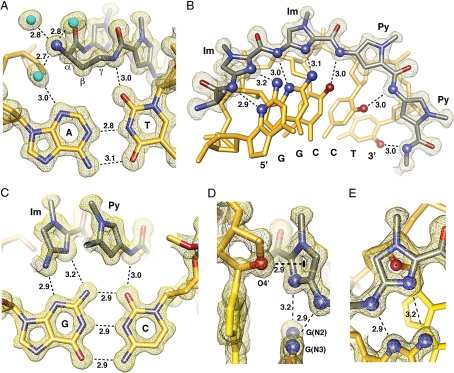

The conformational constraints imposed by the turn unit result in ring placement that is an intermediate of ring-over-ring and ring-over-amide. This alignment allows the ring pairs to remain in phase with the edges of the Watson-Crick base pairs as the polyamide adopts an isohelical conformation complementary to DNA helix. This is highlighted by comparison to the 2:1 structure in which the rings lie over the carboxamide linkages of the adjacent strand (5). The conformational constraints imposed by the turn and inability of the ligand to slip into a possibly more preferred orientation may impact the overall DNA structure by inducing bending and other distortions accommodated by the plasticity of DNA. The preorganized cycle may have a significant entropic driving force leading to increased affinity by locking out unproductive conformations and alternate binding modes. In addition, we find a shell of highly ordered water molecules around the α-ammonium substituent and a water-mediated hydrogen bond from the ammonium to the N3 lone-pair of the adenine under the turn. The hydration pattern around the turn is highly conserved at both ends of the structure and the water-mediated hydrogen bonds are within ≈2.7–2.9 Å from the ammonium to water to the adenine lone-pair (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Direct and water-mediated noncovalent molecular recognition interactions. (A) Geometry of the α-amino turn interacting with the AT base pair through water-mediated hydrogen bonding interactions. Structural basis for the turn preference for AT versus GC is demonstrated by the β-methylene conformational preference, which points down toward the DNA minor-groove floor within van der Waals contact distance of the adenine base. (B) Isolated view of one-half of the macrocyclic-polyamide showing hydrogen bond distances made to the DNA minor groove floor by the imidazoles and amides of compound 1. (C) Im-Py pair showing the mechanism for GC specificity. (D) Interaction of the O4′ oxygen of a deoxyribose sugar with the terminal imidazole aromatic ring through a lone-pair-π interaction. The sugar conformation is C2′-endo at the N-terminal imidazole of the polyamide with the sugar oxygen lone-pair pointing directly to the centroid of the imidazole ring. The distance between the sugar oxygen and the ring centroid is 2.90 Å, which is less than the sum of the van der Waals radii to any atom in the imidazole ring. Electrostatic potential maps calculated at the HF/3–21g* level of theory show the slightly electropositive nature of the imidazole ring under these conditions (Fig. S6). (E) View of the O4′ deoxyribose oxygen atom looking through the imidazole ring showing the ring centroid superimposed on the oxygen atom. All distances are reported in angstroms (Å), and all electron density maps are contoured at the 1.0 σ level (Im, imidazole; Py, pyrrole).

The amide NHs and imidazole lone-pairs form a continuous series of direct hydrogen bonds to the floor of the DNA minor-groove, while the imidazoles impart specificity for the exocyclic amine of guanine through relief of a steric interaction and a G(N2-hydrogen)-Im (lone-pair) hydrogen bond. The amides linking the aromatic rings and the turns contribute hydrogen bonds to the purine N3 and pyrimidine O2 lone-pairs. All amides are within hydrogen bonding distance of a single DNA base (≈3.0 Å average; Figs. S3 and S4). In all, there are 10 direct amide hydrogen bonds (average distance = 2.97 Å), 4 direct imidazole hydrogen bonds (2 terminal average distance = 3.27 Å and 2 internal average distance = 3.05 Å), and 2 (R)-α-ammonium turn water-mediated hydrogen bonds (average distance amine to water = 2.75 Å and average distance from the water to adenine N3 = 2.98 Å) to the floor of the DNA minor groove with at least 1 interaction for all 12 DNA base pairs in the 6-bp binding site for a total of 16 hydrogen bond interactions between the cyclic polyamide and the floor of the DNA minor-groove. These 16 hydrogen bonds use every heteroatom of the polyamide presented to the floor of the DNA minor-groove, which exactly matches the total number of Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds between all of the DNA base pairs in the 6-bp binding site (Fig. S5). In addition to these 16 hydrogen bonds, we find unique weak interactions in the form of lone-pair-π interactions (27, 28) between the center of the leading imidazole ring and the lone-pair of the adjacent deoxyribose O4′ oxygen (Fig. 4 D and E). This interaction is only observed for the terminal imidazole aromatic ring. Analysis of qualitative electrostatic potential surfaces substantiates the electropositive nature of the imidazole when buried in the minor groove of DNA and electrostatically preturbed by specific interaction of the lone-pair with the exocyclic amine of guanine (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6) (29).

The crystal structure highlights the DNA structural distortion induced upon polyamide minor-groove binding and provides an allosteric model for disrupting transcription factor-DNA interfaces in the promoters of selected genes. Allosteric control over transcription factor regulatory networks (30–32) by small molecules that bind distinct locations on promoter DNA provides a mechanism for inhibiting excess transcription factor activity (1, 2, 19, 33).

Materials and Methods

General.

Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Hampton Research and were used without further purification. Water (18 MΩ) was purified using a Millipore MilliQ purification system. Analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was conducted on a Beckman Gold instrument equipped with a Phenomenex Gemini analytical column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), a diode array detector, and the mobile phase consisted of a gradient of acetonitrile (MeCN) in 0.1% (vol/vol) aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Preparative HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 system equipped with a solvent degasser, diode array detector, and a Phenomenex Gemini column (5-μm particle size, C18 110A, 250 × 21.2 mm, 5 μm). A gradient of MeCN in 0.1% (vol/vol) aqueous TFA was used as the mobile phase. UV-Vis measurements were made on a Hewlett-Packard diode array spectrophotometer (Model 8452 A) and polyamide concentrations were measured in 0.1% (vol/vol) aqueous TFA using an extinction coefficient of 69,200 M−1·cm−1 at λmax near 310 nm. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was performed on an Applied Biosystems Voyager DR Pro spectrometer using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as matrix.

Synthesis and Purification.

Polyamide 1 was synthesized by solid-phase synthesis methods (34, 35) on oxime resin (SI Text and Fig. S1) and purified by reverse-phase HPLC (Fig. S2).

Oligonucleotide Purification and Crystallization.

Oligonucleotides were purchased HPLC-purified from Trilink Biotechnologies. Before use, oligonucleotides were de-salted using a Waters Sep-Pak cartridge (5 g, C-18 sorbent). The Sep-Pak was prewashed with acetonitrile (25 mL, 3×) followed by MilliQ water (25 mL, 3×). The oligonucleotide was dissolved in 5 mL 2.0 M NaCl and loaded directly onto the sorbent followed by a wash with 5 mL 2.0 M NaCl and 250 mL MilliQ water. The oligonucleotide was eluted with acetonitrile:water (1:1) and lyophilized to dryness. Single strand DNA was quantitated by UV-Vis spectroscopy. Crystals were obtained after 2–8 weeks from a solution of 0.5 mM duplex DNA, 0.65 mM polyamide, 21% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), 35 mM calcium acetate, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, equilibrated in sitting drops against a reservoir of 35% MPD at 4 °C. Crystals were collected in Hampton nylon CryoLoops (10 μm, 0.1 mm) and flash-cooled to 100 K before data collection.

Polyamides Data Collection, Structure determination, and Refinement.

Polyamide-DNA crystals grew in space group P1 with unit cell dimensions a = 22.500, b = 25.140, c = 29.090, α = 66.53, β = 79.28, γ = 79.57, and 1 polyamide-duplex DNA complex in the asymmetric unit. This data set was collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) beamline 12–2 with a MAR Research imaging plate detector at wavelength 0.97 Å. DNA only crystals grew in space group C2 (C 1 2 1) with unit cell dimensions a = 31.827, b = 25.636, c = 34.173, α = 90, β = 116.72, γ = 90, and 1 DNA strand in the asymmetric unit. This data set was collected at SSRL beamline 11–1 with a MAR Research imaging plate detector at wavelength 0.999 Å (Table S1).

Data were processed with MOSFLM (36) and SCALA (37) from the CCP4 suite of programs (37). Both crystals were solved by direct methods using the SHELX suite of programs (SHELXD) (38, 39). Model building and structure refinement was done with Coot (40) and REFMAC5 (41). The final polyamide-DNA complex was refined to an R factor of 9.8% and an Rfree of 13.6%. The final DNA structure was refined to an R factor of 10.9% and an Rfree of 14.3%. Anisotropic B factors were refined in the final stages and riding hydrogens included (Table S1).

Structure Analysis and Figure Preparation.

DNA helical parameters were calculated using the program Curves (42). Molecular electrostatic potential maps were calculated at the HF/3–21g* level using the Gamess program (Fig. S6) (43–45). Distance measurements and least squares fitting procedures for ring-centroid measurements were performed using UCSF Chimera (46) and Mercury (47). Structural figures were prepared using UCSF Chimera.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Synchrotron data were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) beamlines 11–1 and 12–2. We thank Douglas Rees valuable discussions, Jens Kaiser and Michael Day for their guidance with data collection and structure determination, and the staff of the SSRL for their assistance during crystal screening and data collection. Operations at SSRL are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health. We acknowledge the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for support of the Molecular Observatory at Caltech. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health and a Kanel Foundation predoctoral fellowship (to D.M.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3I5L and 3I5E).

An average minor groove width of ≈7 Å has been calculated by subtracting the value of 5.8 Å, to account for the phosphate Van der Waals radii, from the measured phosphate- phosphate distance of 12.8 Å reported in the NCP-polyamide structures from ref. 25.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0906532106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dervan PB. Molecular recognition of DNA by small molecules. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2215–2235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dervan PB, Edelson BS. Recognition of the DNA minor groove by pyrrole- imidazole polyamides. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:284–299. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trauger JW, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Recognition of DNA by designed ligands at subnanomolar concentrations. Nature. 1996;382:559–561. doi: 10.1038/382559a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White S, Szewczyk JW, Turner JM, Baird EE, Dervan PB. Recognition of the four Watson-Crick base pairs in the DNA minor groove by synthetic ligands. Nature. 1998;391:468–470. doi: 10.1038/35106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kielkopf CL, Baird EE, Dervan PB, Rees DC. Structural basis for G. C recognition in the DNA minor groove. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:104–109. doi: 10.1038/nsb0298-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kielkopf CL, et al. A structural basis for recognition of A. T and T.A base pairs in the minor groove of B- DNA. Science. 1998;282:111–115. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu CF, et al. Completion of a programmable DNA- binding small molecule library. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:6146–6151. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelson BS, et al. Influence of structural variation on nuclear localization of DNA-binding polyamide-fluorophore conjugates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2802–2818. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickols NG, Jacobs CS, Farkas ME, Dervan PB. Improved nuclear localization of DNA-binding polyamides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:363–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu CF, Dervan PB. Quantitating the concentration of Py-Im polyamide- fluorescein conjugates in live cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5851–5855. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottesfeld JM, et al. Sequence-specific recognition of DNA in the nucleosome by pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:615–629. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suto RK, et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olenyuk BZ, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor with a sequence-specific hypoxia response element antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16768–16773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407617101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kageyama Y, et al. Suppression of VEGF transcription in renal cell carcinoma cells by pyrrole-imidazole hairpin polyamides targeting the hypoxia responsive element. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:317–324. doi: 10.1080/02841860500486648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickols NG, Jacobs CS, Farkas ME, Dervan PB. Modulating hypoxia-inducible transcription by disrupting the HIF-1-DNA interface. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:561–571. doi: 10.1021/cb700110z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickols NG, Dervan PB. Suppression of androgen receptor-mediated gene expression by a sequence-specific DNA-binding polyamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10418–10423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuda H, et al. Development of gene silencing pyrrole-imidazole polyamide targeting the TGF-beta1 promoter for treatment of progressive renal diseases. J Am Soc Nephrology. 2006;17:422–432. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao EH, et al. Novel gene silencer pyrrole- imidazole polyamide targeting lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 attenuates restenosis of the artery after injury. Hypertension. 2008;52:86–92. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen-Hackley DH, et al. Allosteric inhibition of zinc-finger binding in the major groove of DNA by minor-groove binding ligands. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3880–3890. doi: 10.1021/bi030223c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Clairac RPL, Geierstanger BH, Mrksich M, Dervan PB, Wemmer DE. NMR characterization of hairpin polyamide complexes with the minor groove of DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7909–7916. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins CA, et al. Controlling binding orientation in hairpin polyamide DNA complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5235–5243. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkins CA, Baird EE, Dervan PB, Wemmer DE. Analysis of hairpin polyamide complexes having DNA binding sites in close proximity. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12689–12696. doi: 10.1021/ja020335b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Q, et al. NMR structure of a cyclic polyamide-DNA complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7958–7966. doi: 10.1021/ja0373622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suto RK, et al. Crystal structures of nucleosome core particles in complex with minor groove DNA-binding ligands. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:371–380. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edayathumangalam RS, Weyermann P, Gottesfeld JM, Dervan PB, Luger K. Molecular recognition of the nucleosomal “supergroove.”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6864–6869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401743101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinemann U, Alings C. Crystallographic study of one turn of G/C-rich B-DNA. J Mol Biol. 1989;210:369–381. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egli M, Sarkhel S. Lone pair-aromatic interactions: To stabilize or not to stabilize. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:197–205. doi: 10.1021/ar068174u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallivan JP, Dougherty DA. Can lone pairs bind to a π system? The water- hexafluorobenzene interaction. Org Lett. 1999;1:103–106. doi: 10.1021/ol990577p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mecozzi S, West AP, Dougherty DA. Cation-π interactions in aromatics of biological and medicinal interest: Electrostatic potential surfaces as a useful qualitative guide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10566–10571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogan M, Dattagupta N, Crothers DM. Transmission of allosteric effects in DNA. Nature. 1979;278:521–524. doi: 10.1038/278521a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panne D, Maniatis T, Harrison SC. An atomic model of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cell. 2007;129:1111–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavelle C. DNA torsional stress propagates through chromatin fiber and participates in transcriptional regulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:146–154. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0208-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moretti R, et al. Targeted chemical wedges reveal the role of allosteric DNA modulation in protein-DNA assembly. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:220–229. doi: 10.1021/cb700258r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baird EE, Dervan PB. Solid phase synthesis of polyamides containing imidazole and pyrrole amino acids. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:6141–6146. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belitsky JM, Nguyen DH, Wurtz NR, Dervan PB. Solid-phase synthesis of DNA binding polyamides on oxime resin. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:2767–2774. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leslie AGW. Recent changes to the MOSFLM package for processing film and image plate data. Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr A. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lavery R, Sklenar H. Curves 5.2: Helical analysis of irregular nucleic acids. Biochimie Theorique CNRS URA. 1997;77 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt MW, et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J Comput Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Binkley JS, Pople JA, Hehre WJ. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. 21. Small split-valence basis sets for first-row elements. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:939–947. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pietro WJ, et al. Self- consistent molecular orbital methods. 24. Supplemented small split-valence basis sets for second-row elements. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:5039–5048. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macrae CF, et al. Mercury: Visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J Appl Cryst. 2006;39:453–457. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.