Abstract

Testicular orphan nuclear receptor 4 (TR4) is an orphan member of the nuclear receptor superfamily with diverse physiological functions. Using TR4 knockout (TR4−/−) mice to study its function in cardiovascular diseases, we found reduced cluster of differentiation (CD)36 expression with reduced foam cell formation in TR4−/− mice. Mechanistic dissection suggests that TR4 induces CD36 protein and mRNA expression via a transcriptional regulation. Interestingly, we found this TR4-mediated CD36 transactivation can be further enhanced by polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as omega-3 and -6 fatty acids, and their metabolites such as 15-hydroxyeico-satetraonic acid (15-HETE) and 13-hydroxy octa-deca dieonic acid (13-HODE) and thiazolidinedione (TZD)-rosiglitazone. Both electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays demonstrate that TR4 binds to the TR4 response element located on the CD36 5′-promoter region for the induction of CD36 expression. Stably transfected TR4-siRNA or functional TR4 cDNA in the RAW264.7 macrophage cells resulted in either decreased or increased CD36 expression with decreased or increased foam cell formation. Restoring functional CD36 cDNA in the TR4 knockdown macrophage cells reversed the decreased foam cell formation. Together, these results reveal an important signaling pathway controlling CD36-mediated foam cell formation/cardiovascular diseases, and findings that TR4 transactivation can be activated via its ligands/activators, such as PUFA metabolites and TZD, may provide a platform to screen new drug(s) to battle the metabolism syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, diabetes, PPAR, PUFA, TZD

Atherosclerosis is a disease of both lipid disorder and chronic inflammation that results from interactions of modified lipoproteins, monocyte-derived macrophages, T cells, and cells from the vessel wall (1). Foam cell formation has a central role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Uptake of oxidized forms of low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL) induces macrophage maturation to form foam cells, which lead to the fatty streaks characteristic of early atherosclerosis. This uptake is mediated by specific macrophage scavenger receptors, including cluster of differentiation (CD)36 (2) and scavenger receptor A (SRA) (3), which recognize and internalize modified lipoproteins such as oxLDL. Among these 2 SRAs, CD36 accounts for a large proportion of oxLDL uptake by macrophages (4–7). Combined inhibition of SRA and CD36 blocks human and mouse foam cell formation in vitro, yet human subjects carrying CD36 mutation usually have a higher risk for atherosclerosis. CD36 roles in oxLDL-mediated foam cell formation in vitro are clear, but its roles in atherosclerosis in vivo are equivocal, which can be either atherogenic (6–8) or atheroprotective (9–11).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ is one of the major CD36 upstream regulators in which PPARγ/retinoid X receptor (RXR) can bind to DNA responsive elements on its 5′-promoter to modulate CD36 gene expression (12). This upregulation of CD36 by PPARγ can be further enhanced by oxLDL and linoleic acid (13, 14) and PPARγ ligands, including 15d-PGJ2 and antidiabetic drugs (thiazolidinediones, TZDs) (15–18).

Testicular orphan nuclear receptor 4 (TR4) belongs to a nuclear receptor superfamily without an identified ligand. TR4 is closely related to TR2 and RXRs (19). The expression of TR4 was found in all tissues tested including central nervous system, metabolic system, and cardiovascular system (20, 21). TR4−/− mice have significant growth retardation (22), defects in female reproductive function and maternal behavior (22), impaired cerebella function (23), reduced sperm production (24), and reduced myelination (25). Other studies suggested that TR4 might be a master regulator controlling glucose and lipid metabolism (26), which is consistent with the previous report that TR4 has a strong circadian expression in key metabolic tissues, including fat, liver, and muscle (20, 21). TR4 is also highly expressed in immune cells and macrophages. However, its roles within the macrophage remain unknown (27, 28).

Given the facts on TR4 circadian expression profiles, the similarly of its DNA responsive element with PPAR, and the complexity of CD36 in regulating of lipid metabolism, we hypothesize that TR4 is another nuclear receptor that may function as a fatty acid sensor to modulate the CD36-mediated lipid metabolism process. Here we identify a previously undescribed signaling pathway in which TR4 regulates CD36-mediated foam cell formation. More importantly, this TR4-mediated CD36 induction can be activated by its endogenous and exogenous ligands/activators. These findings suggest that TR4 is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that functions as lipid sensor in the metabolism syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

Results

TR4 Plays a Vital Role in Foam Cell Formation.

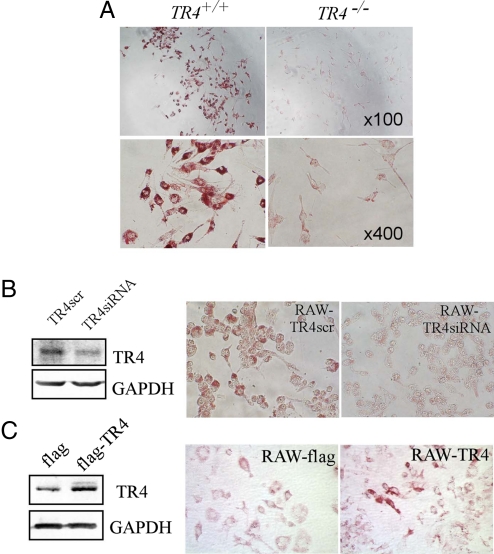

To investigate whether TR4 has a pathophysiological role in cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, we first investigated if TR4 is involved in foam cell formation, a critical step in atherogenesis. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from TR4−/− and wild-type TR4 (TR4+/+) mice were treated with 100 μg/mL oxLDL for 24 h. Microscopic examination of these macrophages revealed a significant accumulation of oil red O-positive droplets in TR4+/+ macrophages, indicative of lipid accumulation. In contrast, little oil red O staining was observed in TR4−/− macrophages. Typical data from 2 pairs of TR4−/− vs. TR4+/+ mice are presented in Fig. 1A. This reduction of foam cell formation in TR4−/− as compared to TR4+/+ macrophages suggests the presence of TR4 is critical for foam cell formation.

Fig. 1.

TR4 modulates foam cell formation. (A) Foam cell formation is decreased in TR4−/− macrophages. Thioglycolate-stimulated peritoneal macrophages from TR4+/+ mice and TR4−/− mice were seeded on a 96-well plate and exposed to 100 μg/mL oxLDL for 24 h. Oil red O staining was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Cells containing oil red O-positive fat droplets were considered foam cells. (B) Knockdown of TR4 in macrophage RAW264.7 cells (RAW-TR4-siRNA) reduces foam cell formation. RAW264.7 cells were infected with retrovirus expressing TR4-siRNA or control TR4-scramble. After selection with puromycin (5 μg/mL) for 3 days, the cells were harvested and TR4 expression levels were examined by Western blot analysis (Left). (Right) RAW-TR4siRNA cells and their empty vector control cells were treated with 100 μg/mL oxLDL for 24 h. Oil red O staining was performed as above. (C) Overexpression of TR4 in macrophage RAW264.7 cells (RAW-TR4) induces foam cell formation. RAW264.7 cells were stably transfected with pCDNA3-flag-TR4 or empty vector pCDNA3-flag. After selection with G418 (500 μg/mL) for 2 weeks, the stable cells were harvested and TR4 protein expression was examined by Western blot analysis. GAPDH served as the loading control (Left). (Right) RAW-TR4 cells and their empty vector control cells were treated with 8 μg/mL oxLDL for 24 h. Oil red O staining was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

To further confirm TR4 roles in foam cell formation, we modulated TR4 expression level in RAW264.7 (RAW) macrophage cells by either overexpression of functional TR4 cDNA or knockdown of TR4 by siRNA interference. These TR4-modulated RAW cells were treated with oxLDL for 24 h after depletion of lipids, and foam cell formation ability was compared. Consistent with the above in vivo observation, oil red O staining revealed that knockdown of TR4 expression (TR4siRNA) resulted in significant reduction of foam cell formation compared to scramble control (TR4src) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, overexpression of TR4 enhanced foam cell formation in RAW cells (Fig. 1C). Together, our in vivo data from TR4−/− mice (Fig. 1A) and in vitro data from RAW cells transfected with TR4-siRNA (Fig. 1B) or functional TR4 cDNA (Fig. 1C) suggest that TR4 plays a vital role in foam cell formation.

TR4 Promotes the Scavenger Receptor CD36 at the mRNA and Protein Levels.

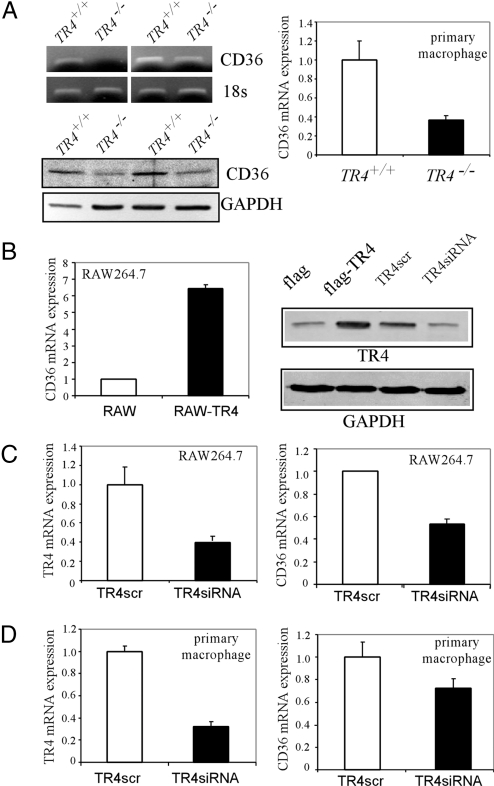

As CD36 has been demonstrated to play an essential role in foam cell formation, we were interested to see if TR4 might modulate CD36 to control foam cell formation. CD36 is mainly responsible for the uptake of oxLDL in macrophages. We used peritoneal macrophages, which expressed CD36, from TR4+/+ and TR4−/− mice to examine CD36 gene expression in response to knockout of endogenous TR4 expression. By using semiquantitative PCR, real-time quantitative PCR, and Western blotting analysis, we found that CD36 mRNA and protein expression in peritoneal macrophages isolated from TR4−/− mice was significantly lower as compared to that from TR4+/+ mice (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

TR4 modulates CD36 expression. (A) CD36 expression is reduced in TR4−/− mice. Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from TR4+/+ and TR4−/− mice. CD36 mRNA (Upper) and protein level (Lower) were then examined by semiquantitative RT-PCR, real-time PCR, and Western blot analysis. (B) Overexpression of TR4 enhances CD36 expression in mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells. The stable cells RAW-TR4 and control RAW-flag, which were established for Fig. 1C, were harvested and CD36 mRNA levels were examined by real-time RT-PCR (Left), and CD36 and TR4 protein expression was examined by Western blot analysis (Right). GAPDH served as the loading control. (C) Knockdown of TR4 expression reduces CD36 expression in mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells. The RAW-TR4siRNA and RAW-TR4scramble cells were harvested and real-time RT-PCR was applied to examine the mRNA levels of TR4 and CD36. The data represent mean ± SD of triplicate samples. (D) Knockdown of TR4 expression reduces CD36 mRNA expression in primary-cultured mouse peritoneal macrophage. WT male mice were injected i.p. with 1 mL of 3.8% thioglycollate medium. After 4 days, mouse peritoneal macrophages were isolated and purified by 2 h adherence. The adherent macrophages were infected with TR4-siRNA or control scramble (TR4scr) for 1 day, then the cells were harvested, and real-time RT-PCR was applied to examine the mRNA levels of TR4 and CD36. The internal control was 18s rRNA and the mRNA expression in control (TR4scr) cells was set as 1. The data represent mean ± SD of triplicate samples.

The upregulation of CD36 by TR4 was confirmed by using established RAW stable cell lines that express functional TR4 cDNA or retroviral-mediated siRNA against TR4. As shown in Fig. 2 B and C, transfection of TR4 increases CD36 expression and knockdown of TR4 reduces CD36 gene expression at the mRNA level. TR4 protein level was also confirmed by Western blotting analysis, where TR4 expression is induced in Flag-TR4 overexpressed RAW cells and reduced in TR4-siRNA RAW cells.

To avoid the indirect effects of CD36 reduction from the total TR4 knockout mouse macrophage, we also used TR4+/+ mouse primary peritoneal macrophages with TR4 knocked down via lentiviral-mediated TR4-siRNA. The results showed that decreasing TR4 (via TR4-siRNA) in peritoneal macrophages resulted in reduction of CD36 gene expression (Fig. 2D). Together, both in vivo data from TR4−/− mice and in vitro data from RAW cells or primary macrophages transfected with either TR4-siRNA or functional TR4 cDNA suggest that TR4 may regulate CD36 expression at both mRNA and protein levels.

TR4 Influences Foam Cell Formation via Modulation of CD36 Expression.

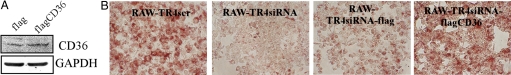

To investigate whether TR4 promotion of foam cell formation is via regulating CD36, we restored functional CD36 cDNA via retroviral transduction into the stable RAW-TR4-siRNA cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, transduction of functional CD36 cDNA resulted in increased CD36 protein expression in stable RAW-TR4-siRNA cells. Furthermore, this increased CD36 expression also resulted in the reversion of reduced foam cell formation caused by knockdown of TR4 via TR4-siRNA (Fig. 3B). These results from Fig. 3 clearly demonstrated that TR4 might influence foam cell formation via modulation of CD36 expression.

Fig. 3.

CD36 rescues TR4-mediated reduced foam cell formation. (A) RAW-TR4siRNA cells were stably transfected with pCDNA3-flag-CD36 or empty vector. After selection with G418 (500 μg/mL) for 2 weeks, the cells were harvested and the CD36 protein expressions were confirmed by Western blot analysis. (B) Overexpression of CD36 rescues TR4-mediated reduced foam cell formation. The cells were seeded on a 96-well plate and exposed to 100 μg/mL oxLDL for 24 h. Oil red O staining was then performed. These data represent results from at least 2 independent experiments.

TR4 Modulates CD36 Expression at the Transcriptional Level.

TR4 is a transcriptional factor that can regulate its target gene expression via binding to TR4 responsive element (TR4RE) located in the gene promoter region. Therefore, we investigated if TR4 can directly regulate CD36 gene expression at the transcriptional level. By sequence analysis and literature search, we found that the CD36 promoter contains a putative TR4RE, with the sequence of 5′-AAGTCAGAGGCCA-3′, which could be also bound by PPAR/RXR (12). A 300-bp CD36 5′ promoter, which contains TR4RE, was linked to a luciferase reporter and tested. As shown in Fig. 4A, TR4 enhanced CD36 5′ promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, TR4 failed to activate the mutated CD36 promoter activity that replaced functional TR4RE with mutated TR4RE (5′-AAGTCAGTTTCA-3′) (12), suggesting this TR4RE is indeed a TR4 binding site (Fig. 4B). Moreover, retrovirus-based siRNA against TR4 reversed the CD36 5′ promoter activity induced by TR4 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

TR4 promotes CD36 promoter activity via TR4RE. (A) TR4 dose-dependently enhanced CD36-luciferase activity. A schematic diagram of the CD36 promoter that contains TR4RE is illustrated. CD36-luc (0.2 μg) was cotransfected with increasing amounts of pCMX-TR4 (0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 μg) into CV-1 cells. The total amount of plasmids was adjusted to equality by vector pCMX. The cells were harvested for the luciferase assay. The data with only CD36-luc transfection (lane 1) were set as 1 and results represent mean ± SD. (B) TR4 significantly activates the activity of WT CD36-luc (P < 0.01; Student's t test) but not mutant (mt) CD36-luc. (C) TR4-siRNA reduces TR4-mediated CD36-luc activity (P < 0.01, Student's t test). Reporter plasmids CD36-luc with TR4-siRNA or TR4scramble were transfected into H1299 cells, and then the cells were harvested for luciferase assay.

TR4 Binds to the CD36 5′ Promoter.

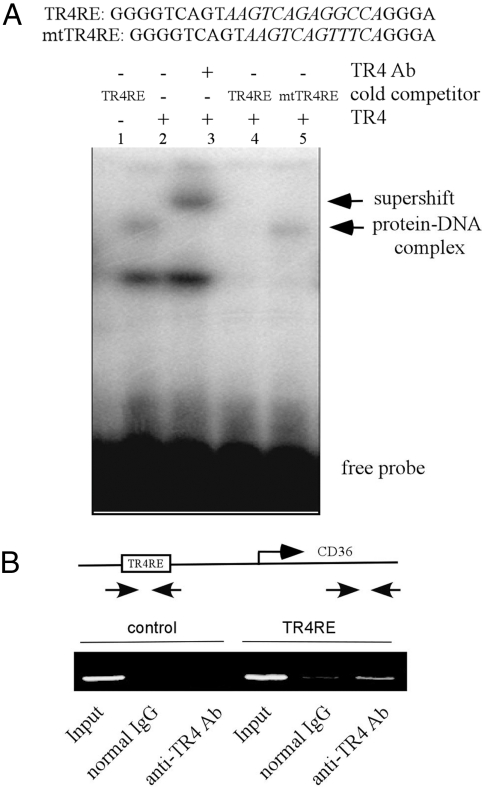

To prove physical interaction between TR4 and TR4RE in vitro and in vivo, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays. As shown in Fig. 5A, incubation of 32P-labeled TR4RE with in vitro transcribed/translated TR4 proteins yielded a slowly migrating band, indicated as a protein–DNA complex (lane 2), and adding an anti-TR4 antibody resulted in a supershift band (lane 3). This specific band formed by the TR4–DNA complex can be competed with an excess amount of TR4RE, but not mutant TR4RE competitor (Fig. 5A, lanes 4 and 5), which further proved the specific binding between TR4 and TR4RE. Next, we performed ChIP assays to determine whether TR4 was able to bind to the endogenous CD36 promoter. DNA–protein complexes in the RAW cells were cross-linked in situ, and the chromatin was isolated and sheared. Subsequently, the chromatin was immunoprecipitated with the anti-TR4 antibody, and the DNA was purified and subjected to PCR using CD36 promoter-specific primers. As shown in Fig. 5B, this primer set specifically amplified a fragment of the predicted size, and adding anti-TR4 antibody caused 4-fold upregulation (Fig. 5B), suggesting that this transcription factor indeed is bound in vivo to the regulatory portion of the CD36 gene. Taken together, both EMSA and ChIP assays suggest that TR4 induces CD36 expression by binding directly to the CD36 promoter region.

Fig. 5.

TR4 directly binds to the TR4RE site of the CD36 promoter region. (A) TR4 directly binds to the TR4RE site of the CD36 promoter region through EMSA. The 32P-labeled probe was incubated with or without in vitro translated TR4 protein. Complexes were resolved on 4.5% polyacrylamide gels. The specific complexes are indicated by arrows. TR4 protein–DNA complexes were also incubated with TR4 antibody. (B) TR4 directly binds to the promoter of CD36 through ChIP assay. RAW cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde (final 1%) for 15 min at room temperature and then subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation using an anti-TR4 antibody or IgG (negative control) and the indicated primers. Reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis.

Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA) Metabolites and TZD Activate TR4-Mediated CD36 Transactivation.

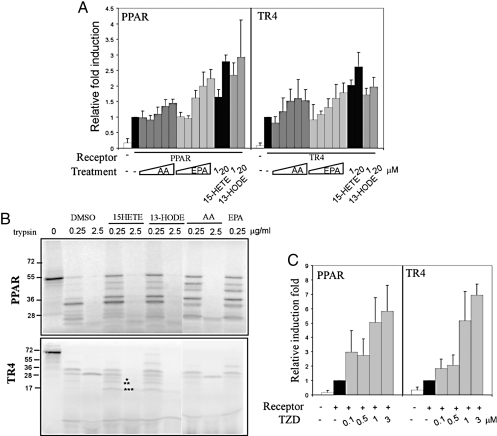

In addition to TR4, another member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, PPARγ, was also reported to be able to modulate CD36 expression (12). Early studies demonstrated that several CD36 upstream activators, such as cytokine (TNFα, IFN-γ, and IL-13), PUFAs [arachidonic acid (AA), linoleic acid (LA), docosahexaenoic (DHA), and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)], PUFA metabolites [15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE)], TZD (rosiglitazone/BRL 49653), and 15-deoxy-Δ-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), were able to modulate CD36 expression. We were interested to see if these activators/ligands were also able to modulate CD36 expression via activation of TR4. As shown in Fig. 6A, we found that AA and EPA, from 1 to 250 μM, mildly induced TR4-mediated and PPARγ/RXR-mediated CD36 expression. Interestingly, the PUFA metabolites, including 15-HETE and 13-HODE, showed much better induction for both TR4- and PPARγ/RXR-mediated CD36 expression.

Fig. 6.

PUFA metabolites and rosiglitazone act as activators/ligands for TR4. (A) PUFA metabolites induced PPAR- and TR4-mediated CD36 activity. Increasing amounts of arachidonic acid (AA), ecosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (1, 10, 50, 100, and 250 μM in BSA), and 15-HETE and 13-HODE (1 and 20 μM in DMSO) were added 24 h after cotransfection of 0.6 μg PPARγ/RXR or TR4 with 0.2 μg CD36-luc into CV-1 cells. After 24 h, cells were harvested for luciferase activity. The relative luciferase activity was calculated while setting pCMX-TR4 in vehicle control as 1. (B) Protease protective peptide mapping was analyzed in liganded PPARγ and TR4. 15-HETE, 13-HODE, AA, and EPA were incubated with 35S-labeled PPARγ and 35S-labeled TR4 for 15 min, and then different concentrations of trypsin (0.25 and 2.5 μg/mL) were added for another 10 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 2× SDS-sample buffer. The protease digestion pattern was resolved by gel electrophoresis in 12.5% (for PPARγ) and 16% (for TR4) SDS/PAGE. (C) Rosiglitazone dose-dependently activates PPARγ- and TR4-mediated CD36-luc activity. Rosiglitazone (0.1, 0.5, 1, and 3 μM in DMSO) was added 24 h after cotransfection of 0.6 μg PPARγ/RXR or TR4 with 0.2 μg CD36-luc into CV-1 cells. After 24 h, cells were harvested for luciferase activity. The relative luciferase activity was calculated while setting pCMX-TR4 in vehicle control as 1.

To further confirm that PUFAs and their metabolites could activate TR4 or PPARγ via direct binding to receptors that include conformational changes, we performed a limited proteolysis assay. As shown in Fig. 6B, 15-HETE-bound TR4 and 13-HODE-bound TR4, as well as 15-HETE-bound PPARγ and 13-HODE-bound PPARγ, display several changed proteolysis resisting fragments (labeled with *) as compared to the DMSO control. The TR4 distinct conformational alterations upon binding to PUFA metabolites strongly suggested that these PUFA metabolites might act as endogenous ligands for TR4 (and PPARγ, refs. 29–31).

TZD, a drug for treating type II diabetes, is a synthetic PPARγ ligand with better binding affinity to PPARγ that results in a stronger induction of CD36 expression (18). As expected, we found that rosiglitazone, a TZD, strongly promotes TR4-induced CD36 transactivation (Fig. 6C). Similar induction was also found when we replaced TR4 with PPARγ/RXR (Fig. 6C). Together, results from Fig. 6 demonstrate that PUFA metabolites and TZD may function as ligands/activators for TR4 (and PPARγ), which suggest TR4, like PPARγ, is a fatty acid sensor that may play vital roles in the metabolism syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

Discussion

Here we demonstrated an important TR4 role in foam cell formation/atherosclerosis via regulation of CD36. We further revealed that TR4 functions as a transcriptional factor that directly binds to the CD36 promoter and regulates CD36 gene expression in macrophage cells. Overexpression of CD36 in the TR4 knockdown macrophages can restore foam cell formation, suggesting that CD36 is involved in TR4-mediated foam cell formation. Interestingly, the TR4 binding site in the CD36 promoter is the same as PPARγ, which controls CD36 gene expression and foam cell formation (32–36). However, we did not observe significant PPARγ gene expression level changes in TR4−/− mouse macrophages (data not shown), suggesting that PPARγ-CD36 signaling may not be able to compensate or rescue the TR4-CD36 signaling.

During screening of CD36 upstream activators, we found that some PPARγ ligands/activators could also stimulate TR4-mediated CD36 expression to different levels, which uncovered a selective array of ligands/activators between TR4 and PPARs with different potencies to activate their downstream target genes. And knockdown of TR4 in the RAW cells did not eliminate CD36 mRNA induction by 15-HETE, 13-HODE, and TZD (data not shown), suggesting other transcriptional factors such as PPARs may also respond to these activators independently from TR4. Because both TR4 and PPARs recognize similar DNA responsive elements, it will be very important to identify distinct ligands/activators that can differentially activate their own distinct target genes that may result in the different effects on the cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.

Identification of TZD, a diabetes drug, functions as a TR4 ligand/acticator to modulate CD36 activity indicates that TZD mediates lipid metabolism via multiple routes. The fact that activating TR4-CD36 signaling by TZD can promote foam cell formation, a key pathological alteration in atherosclerosis/cardiovascular disease, might provide an explanation for the cardiovascular adverse effect found in some TZD-treated type II diabetes patients (37, 38). Further investigation of TR4 roles in vivo, especially in the myocardial cells, and the impact of this identified TR4 upstream regulator affecting TR4 function would be of interest to uncover the complexity of TR4 in regulating lipid metabolism in different tissues under normal physiological and pathological processes.

Taken together, our study identifies the TR4 role in foam cell formation/cardiovascular diseases through regulation of CD36 expression. More importantly, we found that TR4 transactivation can be further promoted via its ligands/activators, such as PUFA metabolites and TZD, suggesting TR4 is a new potential therapeutic target for the battle of TR4-mediated lipid metabolism syndromes.

Methods

Isolation of Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages.

Mice were peritoneally injected with 3 mL of 4% thioglycolate broth media. Four days later, thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were isolated, seeded with RPMI medium supplemented with 8% FBS, and purified by 2 h adherence.

Oil Red O Staining of Foam Cells.

Macrophages were seeded on 96-well plates overnight, cultured in lipid-depleted medium for 1 day, and then treated with oxLDL (8 μg/mL or 100 μg/mL) for 24 h. After washing with PBS, the cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 2 min and then stained with fresh 0.5% oil red O for 2 h. oxLDL was purchased from Intracel.

Analysis of Atherosclerosis. Aortas were collected and stained by Sudan IV, as described previously (39). The extent of atherosclerosis in en face mouse aortas was quantified using photoshop software (Adobe) (40).

Cell Culture, Transient Transfection, and Luciferase Assay.

Mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. For the CD36-luc assay, cells (CV-1 and H1299) were seeded in 24-well plates, and reporter plasmids were cotransfected with TR4 or PPARγ/RXR and then treated with BSA-PUFAs (AA and EPA) (41), their metabolites (13-HODE and 15-HETE in DMSO), and TZD (rosiglitazone/BRL 49653). After 24 h, cells were harvested for luciferase assays.

DNA Constructs.

Full-length CD36 was isolated from cDNA of mouse RAW264.7 cells and then subcloned into pCDNA3-flag. Mouse CD36-promoter-300 and mtCD36-promoter were amplified and subcloned into pGL3-basic vector. All of the constructions were verified by sequencing and/or Western blot analysis.

RNA Interference.

The pSuperior.retro.puro vector (OligoEngine) and lentivirus-based pLVTHM vector (Clontech) were used for the expression of shRNAs against TR4. TR4shRNA was generated by targeting a gene-specific sense sequence CGGGAGAAACCAAGCAATT. The scramble control was constructed by targeting the sequence GTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACG. The construction was confirmed by sequencing.

Virus Infection and Generation of Stable Cell Lines.

For retrovirus-mediated infection, phoenix cells were transfected with pSuperior.retro.puro-TR4-siRNA or its control scramble plasmids. To produce recombinant lentivirus, 293T cells were cotranfected with pLVTHM-TR4siRNA or its control scramble plasmid and lentivirus packaging plasmids, using the Superfect method (Qiagen). At 48–72 h after transfection, infectious retrovirus or lentivirus was harvested and filtered through a 0.45-μM filter. The infection was carried out by adding the virus into the RAW264.7 cells or primary-cultured mouse peritoneal macrophages. After 2 days transfection by Superfect or transduction, RAW264.7 cells were selected with 500 μg/mL G418 for 10 days or 5 μg/mL puromycin for 3 days. The stable clones were confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Mouse studies, real-time RT-PCR, Western blot analysis, ChIP assay, and EMSA were described previously (42–44).

Statistical Analyses.

The statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. P < 0.05 is considered significant.

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK073414 and a George Whipple Professorship endowment.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis. The road ahead. Cell. 2001;104(4):503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endemann G, et al. CD36 is a receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(16):11811–11816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama T, Reddy P, Kishimoto C, Krieger M. Purification and characterization of a bovine acetyl low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(23):9238–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Febbraio M, et al. A null mutation in murine CD36 reveals an important role in fatty acid and lipoprotein metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(27):19055–19062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunjathoor VV, et al. Scavenger receptors class A-I/II and CD36 are the principal receptors responsible for the uptake of modified low density lipoprotein leading to lipid loading in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(51):49982–49988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H, et al. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386(6622):292–296. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Febbraio M, et al. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(8):1049–1056. doi: 10.1172/JCI9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babaev VR, et al. Reduced atherosclerotic lesions in mice deficient for total or macrophage-specific expression of scavenger receptor-A. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(12):2593–2599. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witztum JL. You are right too! J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2072–2075. doi: 10.1172/JCI26130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Berkel TJ, et al. Scavenger receptors: Friend or foe in atherosclerosis? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16(5):525–535. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000183943.20277.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore KJ, et al. Loss of receptor-mediated lipid uptake via scavenger receptor A or CD36 pathways does not ameliorate atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2192–2201. doi: 10.1172/JCI24061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JG, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998;93(2):241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kliewer SA, Lehmann JM, Willson TM. Orphan nuclear receptors: Shifting endocrinology into reverse. Science. 1999;284(5415):757–760. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma. Cell. 1998;93(2):229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kliewer SA, et al. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83(5):813–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman BM, et al. 15-Deoxy-delta 12, 14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPAR gamma. Cell. 1995;83(5):803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Regulation of adipocyte gene expression and differentiation by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5(5):571–576. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmann JM, et al. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) J Biol Chem. 1995;270(22):12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YF, Lee HJ, Chang C. Recent advances in the TR2 and TR4 orphan receptors of the nuclear receptor superfamily. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;81(4–5):291–308. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, et al. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006;126(4):801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bookout AL, et al. Anatomical profiling of nuclear receptor expression reveals a hierarchical transcriptional network. Cell. 2006;126(4):789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins LL, et al. Growth retardation and abnormal maternal behavior in mice lacking testicular orphan nuclear receptor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(42):15058–15063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YT, Collins LL, Uno H, Chang C. Deficits in motor coordination with aberrant cerebellar development in mice lacking testicular orphan nuclear receptor 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(7):2722–2732. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2722-2732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mu X, et al. Targeted inactivation of testicular nuclear orphan receptor 4 delays and disrupts late meiotic prophase and subsequent meiotic divisions of spermatogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(13):5887–5899. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5887-5899.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, et al. Loss of testicular orphan receptor 4 impairs normal myelination in mouse forebrain. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(4):908–920. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu NC, et al. Loss of TR4 orphan nuclear receptor reduces phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-mediated gluconeogenesis. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):2901–2909. doi: 10.2337/db07-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schote AB, Turner JD, Schiltz J, Muller CP. Nuclear receptors in human immune cells: Expression and correlations. Mol Immunol. 2007;44(6):1436–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barish GD, et al. A nuclear receptor atlas: macrophage activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(10):2466–2477. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forman BM, Chen J, Evans RM. Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(9):4312–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kliewer SA, et al. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(9):4318–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu HE, et al. Molecular recognition of fatty acids by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Mol Cell. 1999;3(3):397–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80467-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castrillo A, Tontonoz P. PPARs in atherosclerosis: The clot thickens. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(11):1538–1540. doi: 10.1172/JCI23705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joseph SB, Tontonoz P. LXRs: New therapeutic targets in atherosclerosis? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3(2):192–197. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaven SW, Tontonoz P. Nuclear receptors in lipid metabolism: Targeting the heart of dyslipidemia. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:313–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li AC, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands inhibit development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(4):523–531. doi: 10.1172/JCI10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391(6662):79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(24):2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yki-Jarvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1106–1118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palinski W, et al. ApoE-deficient mice are a model of lipoprotein oxidation in atherogenesis. Demonstration of oxidation-specific epitopes in lesions and high titers of autoantibodies to malondialdehyde-lysine in serum. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14(4):605–616. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehr HA, et al. Immunopathogenesis of atherosclerosis: Endotoxin accelerates atherosclerosis in rabbits on hypercholesterolemic diet. Circulation. 2001;104(8):914–920. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.093153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H, Berschneider HM, Du J, Black DD. Apolipoprotein secretion and lipid synthesis: Regulation by fatty acids in newborn swine intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(5 Pt 1):G935–942. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.5.G935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang L, et al. Androgen suppresses PML protein expression in prostate cancer CWR22R cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie S, et al. Regulation of interleukin-6-mediated PI3K activation and neuroendocrine differentiation by androgen signaling in prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Prostate. 2004;60(1):61–67. doi: 10.1002/pros.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang L, et al. Induction of androgen receptor expression by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt downstream substrate, FOXO3a, and their roles in apoptosis of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(39):33558–33565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]