Abstract

Introduction

Kingella kingae, though part of the normal upper respiratory tract and genitourinary tract, is increasingly being recognized as an important human pathogen. During the past decade, it has emerged as a significant pathogen in the pediatric age group primarily causing bacteremia and osteoarticular infections. Adult infection usually occurs in individuals who are severely immunocompromised and most infections have taken the form of septicemia or septic arthritis. Bacteremia due to K. kingae has been reported as the immediate cause of death in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Case presentation

We present a microbiologically confirmed urinary tract infection with K. kingae in an immunocompetent 45-year-old adult woman with post-menopausal bleeding and with a history of clots. Her urine was subjected to culture and sensitivity tests. The isolated colonies were identified as K. kingae because of their typical culture characteristics such as long incubation period required for growth, beta-hemolysis, positive oxidase and negative catalase, urease indole, nitrate and citrate tests. Penicillin G disc test was positive. They were sensitive to all conventional antibiotics.

Conclusion

K. kingae infection is a rare occurrence in immunocompetent adults. Very few cases of microbiologically confirmed infections have been reported so far. The isolation of K. kingae from urine sample has rarely been reported. K. kingae isolates are either missed or misinterpreted by clinical microbiologists. Therefore, K. kingae deserves recognition as a pathogen.

Introduction

In 1976, Moraxella kingae was removed from the genus Moraxella and was given a new genus and species name Kingella kingae in the family Neisseriaceae[1]. Besides K. kingae, other species belonging to the genus Kingella are K. denitrificans, K. indolegenes and K. oralis. K. kingae exhibits a variable morphology (cocci, short Gram-negative coccobacilli to medium sized rods) and is considered to be a normal flora of the upper respiratory tract and genitourinary tract [2]. It has been associated with infections in children under 6 years and immunocompromised individuals [2].

Poor oral hygiene, pharyngitis and mucosal ulceration are the predisposing factors for K. kingae infections [2,3]. K. kingae bacteremia without endocarditis has also been reported in immunocompetent adults following dental manipulations [4]. K. kingae has specific tissue tropism for cardiac, valvular, joint space, and skeletal tissue and has been isolated from cases of bacteremia, endocarditis, bone and joint infection in various samples such as blood, joint fluid, and urine [5].

We report an adult patient with urinary tract infection from whom K. kingae has been isolated in urine.

Case presentation

A 45-year-old woman was admitted to the gynaecology ward of Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences Hospital, Narketpally complaining of post-menopausal bleeding with passing of clots for the previous 18 months. She also complained of burning micturition.

Urine was sent for culture and sensitivity tests. It was turbid and routine urine microscopic examination revealed the presence of 5 to 8 pus cells per high power field. Urine was inoculated in blood agar, MacConkey's agar and incubated at 37°C. Overnight incubation showed no growth. A pure growth of 1 mm round, convex β-hemolytic colonies was observed on blood agar after 48 hours of incubation, with no growth on MacConkey's agar (Figure 1). Gram stain of the isolated colonies showed varied morphology (cocci, diplococci, coccobacilli) (Figure 2). They were non-motile, oxidase-positive but were negative for catalase (Moraxella and Neisseria were positive), indole (K. indolegenes was positive), citrate, urease, and nitrate (K. denitrificans was positive). Only glucose and maltose (K. oralis was also positive for sucrose) were fermented. The Gram stained smear of the first subculture from blood agar showed short Gram-negative bacilli (Figure 3). Simultaneously, the Penicillin G disc test [6] was performed and revealed Gram-negative plump, elongated rods (Neisseria were negative) (Figure 4). The isolated colonies were found to be susceptible to penicillin (10 µg), ampicillin (25 µg), oxacillin (1 µg), gentamicin (30 µg), amikacin (30 µg), TMP-SMX (25 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), ceftriaxone (30 µg), norfloxacin (10 µg), netilmicin (30 µg) and nalidixic acid (30 µg). The isolated organism was identified as K. kingae because of its fastidious nature, slow growth, β-hemolysis, varied Gram morphology, oxidase positivity, catalase negativity and positive penicillin G disc test.

Figure 1.

Growth on Blood agar after 48 hours of aerobic incubation showing pinpoint translucent haemolytic colonies.

Figure 2.

Gram stain picture on day one showing Gram-negative cocci ' coccobacilli.

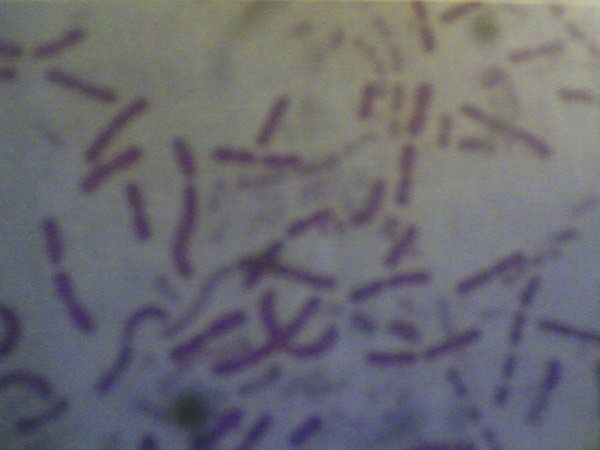

Figure 3.

Gram stain picture of first subculture showing Gram-negative bacilli.

Figure 4.

Gram stain picture of colonies grown in the presence of penicillin (Penicillin G disc test) showing elongated Gram-negative bacilli.

Discussion

K. kingae, though a part of the normal upper respiratory tract and genitourinary tract, is increasingly being recognized as an important human pathogen. During the past decade, it has emerged as a significant pathogen in the pediatric age group primarily causing bacteremia and osteoarticular infections [7,8]. Adult infection usually occurs in individuals who are severely immunocompromised and most infections have taken the form of septicemia or septic arthritis. Bacteremia due to K. kingae has been reported as the immediate cause of death in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [2].

K. kingae infection is a rare occurrence in immunocompetent adults. Very few cases of microbiologically confirmed infections have been reported so far [9]. The isolation of K. kingae from urine samples has rarely been reported [6]. We isolated K. kingae from the urine of an immunocompetent 45-year-old woman with post-menopausal bleeding and with clots for the previous 18 months. In this patient, the possible source of K. kingae was the resident genital flora. Due to the regular flow of clots and tissue, the organism could have gained access through the urethra causing ascending urinary tract infection. Kingellae are nutritionally fastidious Gram-negative bacilli requiring 48 hours of incubation before reaching a colony size of 1 mm diameter. They are oxidase-positive, catalase-negative (Moraxella are positive) and positive for the Penicillin G disc test. Of all of the species, K. kingae is β-hemolytic on sheep blood agar [2]. The isolation of K. kingae is often either missed or misinterpreted. Cases of K. kingae infection are on the rise in children as well as in immunocompromised and immunocompetent adults. Therefore, K. kingae deserves recognition as a pathogen.

Abbreviations

AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KVR analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the urine culture. SKM was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of all teaching and technical staff at Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences.

References

- Henriksen SD, Bovre K. Transfer of Moraxella kingae Henriksen and Bøvre to the genus Kingella gen. nov. in the family Niesseriaceae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1976;26:447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Winn WC, Allen S, Janda WM, Koneman EW, Schreckenberger PC, Procop G, Baker Woods G. Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 6. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006. pp. 472–473. [Google Scholar]

- Shimeld LA, Rodgers AT. Essentials of Diagnostic Microbiology. Delmar Learning; 1999. p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- Roiz MP, Peralta FG, Arjona R. Kingella kingae bacteremia in an immunocompetent adult host. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1916. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1916-1916.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuselis G, Barnishan J. In: Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 2. Mahon CRManuselis G, editor. Saunders; 2000. p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Long KS, Thomas JG, Barnishan J. In: Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 2. Mahon CRManuselis G, editor. Saunders; 2000. p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Yagupsky P, Dagan R. Kingella kingae: An emerging cause of invasive infections in young children. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:860–866. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagupsky P, Dagan R, Howard CW, Einhorn M, Kassis I, Simu A. High prevalence of Kingella kingae in joint fluid from children with septic arthritis revealed by the BACTEC blood culture system. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1278–1281. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1278-1281.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme PA, Van Harpen CM, Meis JF. An adult case of oral infection with Kingella kingae. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:105–107. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]