Abstract

Detection of viral nucleic acids is central to antiviral immunity. Recently, DAI/ZBP1 (DNA-dependent activator of IRFs/Z-DNA binding protein 1) was identified as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor and shown to activate the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factors, leading to type-I interferon production. DAI-induced IRF activation depends on TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), whereas signalling pathways and molecular components involved in NF-κB activation remain elusive. Here, we report the identification of two receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motifs (RHIMs) in the DAI protein sequence, and show that these domains relay DAI-induced NF-κB signals through the recruitment of the RHIM-containing kinases RIP1 and RIP3. We show that knockdown of not only RIP1, but also RIP3 affects DAI-induced NF-κB activation. Importantly, RIP recruitment to DAI is inhibited by the RHIM-containing murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) protein M45. These findings delineate the DAI signalling pathway to NF-κB and suggest a possible new immune modulation strategy of the MCMV.

Keywords: NF-κB, cytomegalovirus, type I interferon, DNA sensor

Introduction

Detection of viral nucleic acids by the host's innate immune system leading to the production of type I interferons (IFNs) is a crucial event in the induction of antiviral responses and the establishment of the so-called ‘antiviral state' (Stetson & Medzhitov, 2006a). Viral RNA sensors comprise endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLR) 3, 7 and 8, as well as the cytoplasmic helicases retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5; Meylan & Tschopp, 2006). On sensing viral RNA species, these receptors induce downstream signalling events, resulting in the activation of transcription factors that control IFN-β expression—namely, interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 3 and 7, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1; Meylan & Tschopp, 2006).

DNA from viral, bacterial or even host origin can also induce strong innate immune responses (Okabe et al, 2005; Stetson & Medzhitov, 2006b; Muruve et al, 2008). Delivery of double-stranded DNA in its canonical B helical form (B-DNA) into the cytoplasm results in type-I IFN production that occurs in a TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-dependent, but TLR9-independent manner (Ishii et al, 2006; Stetson & Medzhitov, 2006b). The IFN-inducible protein DNA-dependent activator of IRFs (DAI), also known as DLM-1 or Z-DNA binding protein (ZBP1)) was recently identified as the first cytosolic DNA receptor (Takaoka et al, 2007). DAI binds to transfected B-DNA in the cytoplasm, and this induces the recruitment of TBK1 and IRF3 to its carboxy-terminal region. IFN responses to transfected B-DNA are potentiated by DAI overexpression; in reverse, IRF and NF-κB activation, as well as the subsequent induction of IFNs, are diminished by DAI knockdown (Takaoka et al, 2007; Wang et al, 2008). Although DAI requirements for DNA-induced type-I IFN production vary among cell types, and data from DAI-deficient mice indicate that additional DNA-sensing molecules must exist (Ishii et al, 2008), DAI represents the only cytoplasmic DNA receptor identified so far for type-I IFN production and NF-κB activation. A second DNA sensor recently discovered, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), seems to mediate only inflammasome activation (Burckstummer et al, 2009; Fernandes-Alnemri et al, 2009; Hornung et al, 2009; Roberts et al, 2009). DAI signalling pathways remain poorly defined (Takaoka & Taniguchi, 2008): DAI has been shown to interact with TBK1 to mediate IRF3 activation, whereas the mechanisms of NF-κB-pathway activation by DAI have only recently begun to emerge (Kaiser et al, 2008).

Here, we show that the DAI sequence contains two receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motifs (RHIMs) that are essential for the recruitment of RIP1 and RIP3, and to mediate NF-κB activation; both kinases contribute to DAI-induced NF-κB activation. Furthermore, we observe that RIP3 undergoes autophosphorylation on binding to DAI. Interestingly, the murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) RHIM-containing protein M45 blocks DAI signalling by disrupting the RHIM-based DAI–RIP1/3 interaction, suggesting a possible new immune modulation strategy of the MCMV.

Results And Discussion

DAI/ZBP1 recruits RIP1 and RIP3 through RHIM domains

Analysis of the DAI amino-acid sequence revealed, in addition to the two known amino-terminal Z-DNA binding domains Zα and Zβ, two other conserved regions located in the central portion of the protein (supplementary Fig S1 online). Further analysis identified these two sequences as potential RHIMs (RHIM1 and RHIM2; Fig 1A), which are known to mediate homotypic protein–protein interactions. For example, a RHIM is present in the TLR-adaptor protein TRIF, in which it is responsible for the recruitment of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3, two other RHIM-domain-containing proteins (Meylan et al, 2004). Interaction between RIP1 and RIP3 was also shown to take place through a homotypic RHIM–RHIM interaction (Sun et al, 2002). In TLR3 signalling, the RHIM-dependent TRIF–RIP1 interaction is crucial for NF-κB activation, whereas RIP3 competes for this interaction and thus acts as an inhibitor of TLR3-mediated NF-κB activation (Meylan et al, 2004).

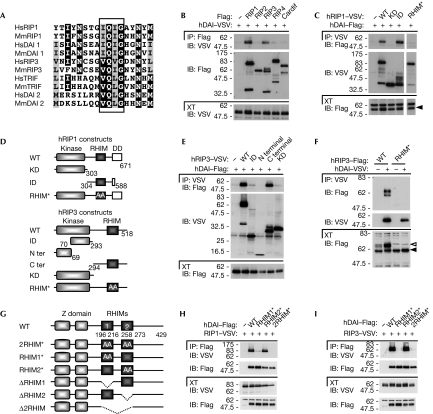

Figure 1.

DAI/ZBP1 contains two RHIM domains that mediate the recruitment of RIP1 and RIP3. (A) Sequence alignment of the RHIM domains of human and murine RIP1, RIP3, TRIF and DAI. The four amino-acid motif crucial for RHIM function is boxed. The black and grey shading indicate more than 60% amino-acid-sequence identity and similarity, respectively. (B,C,E,F,H,I) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated VSV or Flag constructs. Immunoprecipitates and cell extracts were analysed by immunoblot. In (F), white and black arrowheads indicate modified and unmodified RIP3, respectively (see text and Fig 3C–E) (D) Domain architecture of RIP1 and RIP3, and schematic views of deletion constructs used in (C), (E) and (F). RHIM* denotes the construct with alanine substitutions of the four amino acids highlighted in (A). (G) Domain architecture of human DAI and schematic views of the constructs used in this study. RHIM* denotes the construct with alanine substitutions of the four amino acids highlighted in (A) in the indicated RHIM domains. DAI, DNA-dependent activator of IRFs; DD, death domain; HEK, human embryonic kidney; Hs, human; IB, immunoblot; ID, intermediate domain; IP, immunoprecipitates; KD, kinase domain; Mm, murine; RHIM, RIP homotypic interaction motif; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; WT, wild type; XT, cell extracts; ZBP1, Z-DNA binding protein 1.

The presence of two RHIM domains in DAI suggested that, similar to TRIF, DAI might also interact with one or both of the RIP kinases. Indeed when co-expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cells, human DAI co-immunoprecipitated with RIP1 and RIP3, but not with RIP2 and RIP4 (which lack RHIMs), nor with Cardif (MAVS, IPS-1, VISA), the adaptor protein essential for RIG-I/MDA5 signalling (Fig 1B; Meylan et al, 2005). Similarly, murine DAI interacted with RIP1 and RIP3 (supplementary Fig S2 online).

To map the DAI–RIP1/3 interaction site, various deletion constructs were generated (Fig 1D). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that only the constructs of RIP1 and RIP3 that retained the RHIM domain-coding region were able to bind co-expressed DAI (Fig 1C,E). Four residues in the RHIM domain of RIP1 and RIP3 were previously shown to be essential for RHIM-based interactions (Sun et al, 2002). When these crucial residues were mutated to alanines, a total impairment of DAI recruitment was observed (Fig 1C,F).

To investigate the involvement of the two DAI RHIM domains in RIP1/3 recruitment, we also generated DAI constructs with alanine substitutions in the corresponding four core residues of their RHIMs, as well as DAI deletion constructs for the first or second RHIM, or entire region comprising these two domains (Fig 1G). All DAI constructs lacking a functional RHIM1 were unable to bind to RIP1/3, whereas the targeting of the RHIM2 did not affect this interaction when DAI and RIPs were overexpressed (Fig 1H,I; supplementary Fig S2C,D online). Taken together, these results show that DAI has two RHIM domains, in addition to the two described Z-DNA binding domains, and that it recruits RIP1 and RIP3 through RHIM–RHIM homotypic interactions.

DAI-induced NF-κB activation is RHIM-dependent

Considering the crucial role of the RHIM-dependent TRIF–RIP1 association in mediating NF-κB activation on TLR3 stimulation, we next examined whether this domain has a similar role in DAI signalling.

Overexpression of human or murine DAI in HEK293T cells activated an NF-κB-dependent promoter in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 2A; data not shown). For this activity, the full-length protein was required, as the N- or C-terminal deletion constructs were inactive, regardless of the presence or absence of the RHIM domains (supplementary Fig S3A online). In contrast to NF-κB, neither human nor murine full-length or deletion DAI constructs significantly activated IRF transcription factors, as monitored by an interferon-stimulated regulatory element promoter (supplementary Fig S3B online; data not shown) or by the upregulation of the interferon-inducible protein RIG-I (supplementary Fig S3C online). By contrast, Cardif or a dominant-active form of RIG-I potently activated IRFs in the same experimental setting, and acted as positive controls.

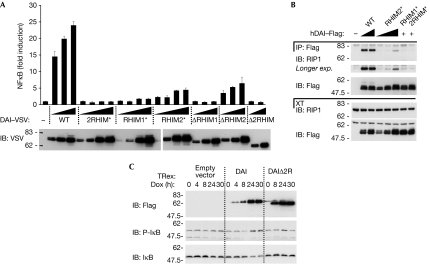

Figure 2.

DAI-induced NF-κB activation is RHIM dependent. (A) HEK239T were transfected with an NF-κB reporter plasmid together with an empty plasmid or increasing doses of the indicated DAI constructs, and were analysed for NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity 24 h later. Data are the mean values±s.d. of three transfection points from one experiment; results are representative of three independent experiments. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated Flag–DAI constructs or an empty vector. IPs and XTs were analysed for the presence of endogenous RIP1 by IB. (C) HEK293-TRex cells inducibly expressing the indicated Flag–DAI constructs or an empty vector were treated with doxycycline (Dox; 200 ng/ml) for the indicated times; XTs were analysed by IB. DAI, DNA-dependent activator of IRFs; HEK, human embryonic kidney; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitates; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; RHIM, RIP homotypic interaction motifs; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; WT, wild type; XT, cell extracts.

DAI constructs with mutations in the first or in both RHIMs were found to be unable to induce NF-κB activation (Fig 2A). Identical results were obtained with the corresponding deletion constructs, supporting the essential requirement of a functional RHIM1 domain. Furthermore, mutation or deletion of DAI RHIM2 resulted in a strong impairment of DAI activity (Fig 2A), indicating that RHIM2 is also important for DAI function.

In accordance with these functional data, we observed that overexpressed wild-type DAI co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous RIP1, and that mutation or deletion of RHIM2 strongly affected this interaction (Fig 2B; supplementary Fig S4A online). This is in contrast to the data with overexpressed proteins (Fig 1H,I) and suggests that the DAI RHIM2 domain also contributes to the recruitment of RIP1 under more physiological conditions. As expected, DAI constructs lacking functional RHIM1 were unable to bind to endogenous RIP1 (Fig 2B; supplementary Fig S4A online).

In addition to these observations, it was also observed that DAI induces NF-κB activation synergistically when co-expressed with RIP1 and RIP3 (supplementary Fig S4B,C online). This effect was not observed on co-expression of DAI 2RHIM* mutant, which is unable to bind to the two RIPs, nor when the RIP3 RHIM mutant was used. It should be noted that a kinase-inactive RIP3 (K50A) mutant did not show the synergistic NF-κB activation with DAI.

To corroborate the results of the NF-κB reporter assay, we generated HEK293-TRex cells expressing full-length or Δ2RHIM DAI in an inducible manner. In this system, induced expression of wild-type DAI led to spontaneous I-κB phosphorylation and degradation, whereas induction of the DAI Δ2RHIM protein had no effect (Fig 2C).

These observations emphasize the ability of DAI to activate NF-κB and further show that both RHIM domains are crucial for this activity.

RIP1 and RIP3 mediate DAI signalling to NF-κB

The results presented above suggest that RIP1 and possibly RIP3 are essential for DAI-mediated NF-κB activation. To verify this, the expression of RIP1 and RIP3 was knocked down using short interfering RNA (siRNA; supplementary Fig S5A,B online). Silencing of RIP1 with two different oligonucleotides (but not a control siRNA) clearly impaired DAI-mediated NF-κB activation (Fig 3A). Interestingly, downregulation of RIP3 using two different siRNAs also resulted in a strong reduction of DAI signalling to NF-κB (Fig 3A). Therefore, it seems that both RIP1 and RIP3 participate in mediating DAI downstream events resulting in NF-κB activation. This situation is different from that which occurs in TRIF signalling, the second RHIM-dependent NF-κB activating pathway, where RIP3 acts as an inhibitor by competing with RIP1 for binding to the RHIM of TRIF (Meylan et al, 2004). In support of the requirement of both kinases for DAI signalling, RIP1 and RIP3 can form a complex with DAI (Fig 3B).

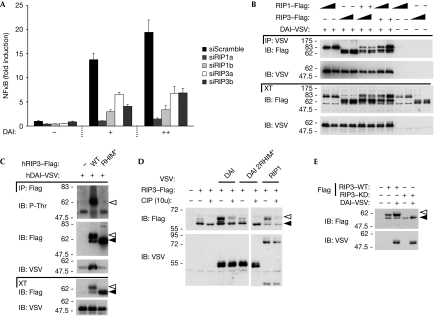

Figure 3.

DAI-induced NF-κB activation requires RIP1 and RIP3. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with 20 nM of the indicated siRNAs and, 36 h later, re-transfected with an NF-κB reporter plasmid together with an empty plasmid or two doses of DAI. NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity was measured 24 h after the second transfection. Data are the mean values±s.d. of three transfection points from one experiment; results are representative of three independent experiments. (B,C) HEK293T cells were transfected with VSV–DAI or an empty vector and the indicated Flag constructs. IP and XTs were analysed by IB. In (B), increasing doses of plasmid are shown. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag–RIP3 or an empty vector and the indicated VSV constructs. At 24 h after transfection, cell lysates were incubated with or without CIP (10 U per 30 μl, 10 min, 37°C) and analysed by IB. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and analysed by IB. In (C–E), white and black arrowheads indicate modified and unmodified RIP3, respectively. CIP, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase; DAI, DNA-dependent activator of IRFs; HEK, human embryonic kidney; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitates; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; RHIM, RIP homotypic interaction motifs; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; XT, cell extracts; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus; WT, wild type.

A further indication that RIP3 is part of the DAI signalling complex comes from the observation that co-expression of these two proteins resulted in the appearance of a form of RIP3 that migrates more slowly on SDS–PAGE, which probably originates from post-translational modifications (Figs 1F, 3C,D). This change was absent when the RIP3 RHIM mutant (Figs 1F, 3C) or the DAI double-RHIM mutant constructs (Fig 3D) were used, but was present on RIP1 and RIP3 co-expression. This suggests that the assembly of the DAI–RIP1–RIP3 complex is necessary to induce RIP3 modifications. To determine the nature of the upper form of RIP3, immunoprecipitates of RIP3 were analysed using antibodies specific for phosphorylated serine (P-Ser), phosphorylated threonine (P-Thr) and ubiquitin. No signal was detected for P-Ser or ubiquitin; by contrast, a strong signal corresponding to the upper form of RIP3 was obtained using the P-Thr antibody (Fig 3C; data not shown). The absence of a P-Thr signal in the RIP3 RHIM-mutant immunoprecipitate argues for its specificity. Furthermore, treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase abolished the basal, as well as the DAI- and RIP1-induced migratory shift of RIP3 (Fig 3D), further indicating that this upper band is a hyper-phosphorylated form. When a kinase-inactive RIP3 (K50A) mutant construct was used, both basal and DAI-induced phosphorylations were abolished (Fig 3E). This suggests that the DAI and RIP3 interaction drives RIP3 autophosphorylation. RIP1 does not seem to be essential for DAI-induced RIP3 phosphorylation as this is still observed after RIP1 knockdown (supplementary Fig S6 online). Our results raise the interesting question of whether the lack of synergy in NF-κB induction between the kinase-inactive RIP3 and DAI (supplementary Fig S4C online) might be due to the absence of DAI-induced RIP3 autophosphorylation.

Collectively, these results show that both RIP1 and RIP3 contribute to DAI-induced NF-κB activation, and that recruitment of RIP3 to DAI induces its autophosphorylation.

The MCMV protein M45 inhibits DAI signalling

Viruses have evolved strategies to interfere with antiviral signalling pathways. A clear example is the RIG-I/MDA5 viral RNA-sensing pathway, which is targeted by various viruses such as hepatitis C or influenza viruses.

In a bioinformatics search for other RHIM-containing proteins, we found that this domain was also present in protein 45 of three related double-stranded DNA-containing herpes viruses: MCMV (or murid herpesvirus1), rat cytomegalovirus and tupaiid herpesvirus 1 (supplementary Fig S7A online). Interestingly, protein 45 of the MCMV (M45) is crucial for productive viral replication in macrophages and endothelial cells (Brune et al, 2001), and is essential for the MCMV spread and pathogenesis in vivo (Lembo et al, 2004). Recently, Upton et al (2008) identified the RHIM of MCMV M45 to be crucial for the suppression of cell death during infection. Moreover, M45 inhibits RIP1-dependent signalling by tumour necrosis factor (TNF; Mack et al, 2008).

These observations led us to hypothesize that M45 could target DAI signalling. M45 is post-translationally processed at amino acid 277 during infection (Lembo et al, 2004) and the RHIM-containing fragment (aa 1–277) retains RIP-binding and cell death suppression activity (Upton et al, 2008). Therefore, we generated a construct corresponding to this polypeptide and tested its ability to bind to DAI, RIP1 and RIP3. As expected, interaction with both RIP kinases was observed (Fig 4A). M451−277 also bound to DAI, which was dependent on functional DAI RHIMs as shown by the absence of binding to the DAI RHIM double mutant (Fig 4A).

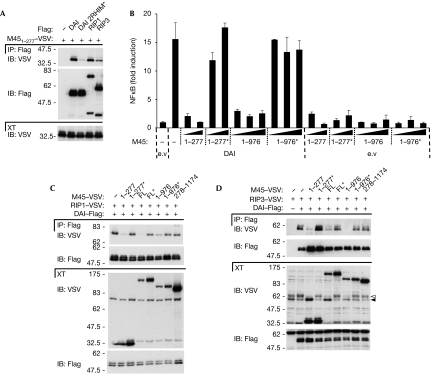

Figure 4.

The RHIM-containing protein M45 of the MCMV inhibits DAI signalling. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with VSV–M451−277 or an empty vector and the indicated Flag constructs. IP and XT were analysed by IB. (B) HEK239T were transfected with an NF-κB reporter plasmid together with an empty plasmid (e.v) or DAI in combination with increasing doses of the indicated M45 constructs (shown in supplementary Fig S6B online) and were analysed for NF-κB-dependent luciferase activity 24 h later. Data are the mean values±s.d. of three transfection points from one experiment; results are representative of two independent experiments. (C,D) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated VSV or Flag constructs. IP and XT were analysed by IB. In (D), white and black arrowheads indicate modified and unmodified RIP3, respectively. The asterisks indicate constructs with alanine substitutions of the four amino acids (highlighted in supplementary Fig S6A online). DAI, DNA-dependent activator of IRFs; FL, full length; HEK, human embryonic kidney; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitates; MCMV, murine cytomegalovirus; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; RHIM, RIP homotypic interaction motifs; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; XT, cell extracts; VSV, vesicular stomatitis virus.

Next we tested the effect of M451−277 on DAI signalling. Co-expression of M451−277 inhibited DAI-induced NF-κB activation in a dose-dependent manner as monitored by reporter assay (Fig 4B). This inhibitory activity was again completely dependent on a functional RHIM, as a RHIM-mutated M451−277 construct had no effect (Fig 4B).

Reports from Upton et al (2008) and Mack et al (2008) showed the ability of M45 to target RIP1. The first identified the RHIM of MCMV M45 to be crucial for suppression of cell death, whereas the second mapped the inhibitory activity of M45 in RIP1-dependent signalling by TNF to its C-terminal portion (aa 977–1174). To clarify which of these two mechanisms account for the effect on DAI signalling, we generated the various M45 constructs used in these studies (supplementary Fig S7B online).

According to Mack et al (2008), M45 constructs with the C-terminal part (aa 977–1174) could reduce TNF-induced NF-κB activation. By contrast, we found that these same constructs, when expressed alone, induced a moderate but consistent NF-κB activation on their own (supplementary Fig S7C online). In support of the requirement for the RHIM, but not the C-terminal domain of M45 to inhibit DAI signalling, we observed that an M45 construct comprising amino acids 1–976 blocked the DAI-induced NF-κB activation, and that this effect was abrogated by mutating the RHIM domain (Fig 4B).

Considering that M451−277 interacts with the DAI RHIM domain, we hypothesized that this could affect the recruitment of RIP1 and RIP3. Indeed, binding of RIP1 and/or RIP3 to DAI was strongly affected by the co-expression of RHIM-containing M45 constructs (Fig 4C,D; data not shown). By contrast, the interaction between DAI and RIP kinases was altered neither by the expression of RHIM-mutated M45 constructs nor by the M45 C-terminal cleavage fragment. Interestingly, RIP3 phosphorylation was inhibited by M45 in an identical RHIM-dependent manner (Fig 4D). Thus, the MCMV M45 protein has the potential to block DAI signalling to NF-κB by interfering with the RHIM-dependent recruitment of RIP1 and RIP3. In line with this, one might consider the idea that M45 could also interfere with the DAI–RIPs complex by targeting not only DAI RHIMs but also RIP1 and RIP3 RHIM domains.

In summary, we have identified DAI as a new RHIM-containing protein, and provide evidence that these domains are crucial for the recruitment of RIP1 and RIP3, and subsequent NF-κB activation, which is in agreement with the recent report from Kaiser et al (2008). Furthermore, the MCMV M45 protein has the potential to block this pathway by disrupting DAI–RIP interactions. This, together with the observation by Upton et al (2008) that M45 is crucial for the suppression of cell death during MCMV infection, makes it highly probable that inhibition of DAI signalling contributes to the requirement of M45 for MCMV replication and pathogenesis in vivo.

Methods

Expression vectors. Full-length human and murine DAI complementary DNAs were amplified from expressed sequence-tag (EST) clones (human DAI, IMAGE: 40121532 (imaGenes GmbH, Berlin, Germany); murine DAI, MMM1013-65907 (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA) by standard PCR with Pwo Superyield polymerase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). A mutation present in the RHIM domain of mouse EST (R197G) was reverted by double PCR. M45 sequence encoding amino acids 1–277 was amplified by standard PCR from total purified MCMV genomic DNA. M45 sequence encoding amino acids 278–1174 was obtained from Genscript Corporation (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Full-length M45 DNA was obtained from this construct by double PCR. DAI/RIP1/RIP3/M45 deletion- and RHIM/kinase domain-mutant constructs were amplified by standard and double PCR, respectively.

In RHIM mutant constructs, alanine substitution targeted the following amino acids: RIP1 (539–542), RIP3 (458–461), DAI (RHIM1: 206–209, RHIM2: 264–267) and M45 (61–64). The fidelity of the PCR amplifications was confirmed by sequencing.

PCR products were cloned into a derivative of pCR3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), in frame with an N-terminal or C-terminal tag, VSV (vesicular stomatitis virus) or Flag.

RIP1, RIP3, RIP2, RIP4, Cardif, RIG-I 2CARD and interferon-stimulated regulatory element reporter constructs were generated as described previously (Meylan et al, 2004; Michallet et al, 2008; Rebsamen et al, 2008).

NF-κB luciferase reporter construct (provided by V. Jongeneel) was derived from κB/thymidinekinase 5 chloramphenicol acetyltransferase construct (Shakhov et al, 1990): the 5-kB site sequence was cloned into pGL2-Basic vector (E1641, Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Phosphatase assay. 24 h after transfection, HEK293T cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) at 4°C. After a centrifugation step (for 10 min, 13,000 r.p.m. at 4°C), supernatant was collected, New England Biolabs (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) buffer-3 added and incubated for 10 min at 37°C with or without 10 units per 30 μl of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase CIP (NEB).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Eckert for critical reading of the paper. J.T. is supported by grants of the Swiss National Science Foundation and the European Union grants Hermione and Apotrain. M-C. M. was a recipient of a fellowship from the European Molecular Biology Organization.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Brune W, Menard C, Heesemann J, Koszinowski UH (2001) A ribonucleotide reductase homolog of cytomegalovirus and endothelial cell tropism. Science 291: 303–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckstummer T et al. (2009) An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol 10: 266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES (2009) AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature 458: 509–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M, Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, Latz E, Fitzgerald KA (2009) AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature 458: 514–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KJ et al. (2006) A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol 7: 40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii KJ et al. (2008) TANK-binding kinase-1 delineates innate and adaptive immune responses to DNA vaccines. Nature 451: 725–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Mocarski ES (2008) Receptor-interacting protein homotypic interaction motif-dependent control of NF-kappa B activation via the DNA-dependent activator of IFN regulatory factors. J Immunol 181: 6427–6434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo D, Donalisio M, Hofer A, Cornaglia M, Brune W, Koszinowski U, Thelander L, Landolfo S (2004) The ribonucleotide reductase R1 homolog of murine cytomegalovirus is not a functional enzyme subunit but is required for pathogenesis. J Virol 78: 4278–4288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack C, Sickmann A, Lembo D, Brune W (2008) Inhibition of proinflammatory and innate immune signaling pathways by a cytomegalovirus RIP1-interacting protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3094–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Burns K, Hofmann K, Blancheteau V, Martinon F, Kelliher M, Tschopp J (2004) RIP1 is an essential mediator of Toll-like receptor 3-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol 5: 503–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Curran J, Hofmann K, Moradpour D, Binder M, Bartenschlager R, Tschopp J (2005) Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature 437: 1167–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Tschopp J (2006) Toll-like receptors and RNA helicases: two parallel ways to trigger antiviral responses. Mol Cell 22: 561–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michallet MC et al. (2008) TRADD protein is an essential component of the RIG-like helicase antiviral pathway. Immunity 28: 651–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruve DA, Petrilli V, Zaiss AK, White LR, Clark SA, Ross PJ, Parks RJ, Tschopp J (2008) The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature 452: 103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe Y, Kawane K, Akira S, Taniguchi T, Nagata S (2005) Toll-like receptor-independent gene induction program activated by mammalian DNA escaped from apoptotic DNA degradation. J Exp Med 202: 1333–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebsamen M, Meylan E, Curran J, Tschopp J (2008) The antiviral adaptor proteins Cardif and Trif are processed and inactivated by caspases. Cell Death Differ 15: 1804–1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TL et al. (2009) HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science 323: 1057–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakhov AN, Collart MA, Vassalli P, Nedospasov SA, Jongeneel CV (1990) Kappa B-type enhancers are involved in lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene in primary macrophages. J Exp Med 171: 35–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB, Medzhitov R (2006a) Antiviral defense: interferons and beyond. J Exp Med 203: 1837–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB, Medzhitov R (2006b) Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity 24: 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, Fairbrother WJ, Dixit VM (2002) Identification of a novel homotypic interaction motif required for the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein (RIP) by RIP3. J Biol Chem 277: 9505–9511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A, Taniguchi T (2008) Cytosolic DNA recognition for triggering innate immune responses. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60: 847–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A et al. (2007) DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature 448: 501–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES (2008) Cytomegalovirus M45 cell death suppression requires receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motif (RHIM)-dependent interaction with RIP1. J Biol Chem 283: 16966–16970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Choi MK, Ban T, Yanai H, Negishi H, Lu Y, Tamura T, Takaoka A, Nishikura K, Taniguchi T (2008) Regulation of innate immune responses by DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) and other DNA-sensing molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5477–5482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials