Abstract

Leptin is an adipose hormone with well characterized roles in regulating food intake and energy balance. A novel neuroprotective role for leptin has recently been discovered; however, the underlying mechanisms are not clearly defined. The purpose of this study was to determine whether leptin protects against delayed neuronal cell death in hippocampal CA1 following transient global cerebral ischemia in rats and to study the signaling mechanism responsible for the neuroprotective effects of leptin. Leptin receptor antagonist, protein kinase inhibitors and western blots were used to assess the molecular signaling events that were altered by leptin after ischemia. The results revealed that intracerebral ventricle infusion of leptin markedly increased the numbers of survival CA1 neurons in a dose-dependent manner. Infusion of a specific leptin antagonist 10 min prior to transient global ischemia abolished the pro-survival effects of leptin, indicating the essential role of leptin receptors in mediating this neuroprotection. Both the Akt and extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling pathways appear to play a critical role in leptin neuroprotection, as leptin infusion increased the phosphorylation of Akt and ERK1/2 in CA1. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of either pathway compromised the neuroprotective effects of leptin. Taken together, the results suggest that leptin protects against delayed ischemic neuronal death in the hippocampal CA1 by maintaining the pro-survival states of Akt and ERK1/2 MAPK signaling pathways.

Keywords: Akt, extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2, global ischemia, leptin antagonist, neuroprotection

Leptin is a 16-kDa non-glycosylated protein hormone, produced primarily by white adipocytes, which functions to regulate food intake and energy balance (Friedman and Halaas 1998). Leptin acts by binding leptin receptors, which are members of the cytokine receptor class I family (Hegyi et al. 2004; Ahima 2005). In the central nervous system, leptin receptors are abundantly expressed in the hypothalamus, and less abundantly expressed in other sites of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum (Mercer et al. 1996; Shibata et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2007c; Guo et al. 2008). The binding of leptin to its receptors activates associated Janus-tyrosine kinase 2, leading to tyrosine residue phosphorylation of the intracellular domains of the receptors. The receptors then serve as docking sites for subsequent signaling events, including the phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and Akt (Banks et al. 2000; Imada and Leonard 2000; Kloek et al. 2002).

The neuroprotective effects of leptin have been reported recently (Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007c; Diano and Horvath 2008; Guo et al. 2008), and are thought to be mediated by leptin receptors. Several downstream signaling pathways are activated following the administration of leptin, including the ERK1/2, Akt and STAT3 pathways (Russo et al. 2004; Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007b; Guo et al. 2008). Furthermore, inhibition of these signaling pathways can attenuate the protective effects of leptin. However, direct evidence has not been reported to support the central role of leptin receptors. A leptin antagonist, which contains three mutations (L39A/D40A/F41A) in leptin and can bind leptin receptors with an affinity similar to that of leptin but does not exert any agonist effect, was recently shown to block the biological function of leptin (Gertler 2006; Zhang et al. 2007c). This antagonist makes it possible to study the essential role of leptin receptors.

Leptin functions via both a central and peripheral mechanisms. The central function of leptin includes the regulation of body weight and energy balance and is mediated by neurons (Friedman and Halaas 1998; Bates and Myers 2003). The peripheral function includes the regulation of blood pressure via endothelial cells (Lembo et al. 2000; Fortuno et al. 2002), and reproduction via germ cells (Almog et al. 2001; Bates et al. 2003; Bluher and Mantzoros 2007). In our previous report, we demonstrated that the systemic administration of leptin decreased the infarct volume induced by focal cerebral ischemia in mice (Zhang et al. 2007b). This neuroprotection by leptin may be provided by both the central and peripheral actions of leptin. It would be constructive to determine if the central action of leptin alone is sufficient to protect brain against ischemic injury. This can be determined by administering leptin via the intracerebroventricular (ICV) route in order to avoid the peripheral action of leptin.

Myocardial infarction and stroke are two major diseases implicated in human death and disability, and cardiac arrest itself can cause severe brain ischemia. This type of brain injury is characterized by subchronic and selective hippocampal CA1 neuronal death, and can be mimicked in a rat model of global cerebral ischemia (Pulsinelli et al. 1982; Chen et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 2006). It is not clear if leptin is also neuroprotective against ischemic injury induced by global cerebral ischemia. We set out to establish whether leptin is neuroprotective against ischemic CA1 neuronal injuries induced by global ischemia in rats. We plan to ascertain whether leptin acts through a central mechanism alone, as well as the role of leptin receptors in neuroprotection.

Materials and methods

The rat model of global ischemia and leptin infusion

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animals used were male adult Sprague–Dawley rats (Hilltop Lab Animals, Scottdale, PA, USA), weighing 300−330 g. Aseptic surgeries were performed using anesthesia of 1.5−2% isoflurane in a mixture of 30% O2 and 70% N2O. Transient global ischemia was induced using a previously described rat model of four-vessel occlusion (Zhang et al. 2006, 2007a). In brief, blood pressure, blood gases, and blood glucose concentration were monitored and remained in the normal range throughout the experiments through left femoral artery catheterization. Rectal temperature was continually monitored and kept at 37−37.5°C using a heating pad and a heating lamp. Brain temperature was monitored using a 29-Ga thermocouple implanted in the left caudate-putamen and kept at 35.8 ± 0.2°C during ischemia. Global ischemia was induced by cauterization and cutting of both vertebral arteries and temporarily occluding both common carotid arteries for 12 min. Electroencephalography (PowerLab, ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) was used to ensure isoelectricity at 10 s post-induction of ischemia. Sham operations were performed in additional animals using identical surgical procedures, except that the common carotid arteries were not occluded.

Recombinant rat leptin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). A stock solution of leptin was prepared according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Leptin at doses of 2, 4 or 6 μg in 10 μL vehicle was infused into the right ICV within 20 min after ischemia with a Hamilton syringe, using the following coordinates from bregma: anteroposterior, −0.8 mm; lateral 1.5 mm; depth, 3.5 mm. In selected experiments, rats were subjected to ICV infusion of both leptin and LY294002 [5 μL of 2 mM/L in dimethylsulfoxide/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)], PD98059 (5 μL of 2 mM/L in dimethylsulfoxide/PBS), or leptin-receptor antagonist (12 μg in 5 μL of 0.1% bovine serum albumin/PBS, a gift from Professor Gertler, Protein Laboratories Rehovot, Israel) 10 min before induction of ischemia.

Histology

For histological analysis, animals were grouped randomly with 8−10 rats in each group. In experimental groups, various amounts of leptin or vehicle were infused into the right ICV at 20 min after ischemia. Animals were killed at three days following global ischemia and the brains were removed and frozen in isopentane cooled by dry ice. 20-μm coronal sections at the level of the dorsal hippocampus were collected and stained with hematoxylin for histological study. The total numbers of healthy neurons in the entire CA1 regions were counted microscopically by two investigators blind to the experimental conditions (Zhang et al. 2006, 2007a).

Detection of DNA fragmentation by nick-translation

The DNA polymerase I-mediated biotin-dATP nick-translation (PANT) assay was performed on fresh-frozen brain sections to detect DNA breaks (Nagayama et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2006, 2007a). The sections were prepared as described previously. The sections were then air-dried, fixed with 10% formalin for 10 min, and washed three times in PBS. The sections were then fixed in ethanol/acetic acid (2 : 1, v/v) for 5 min and washed three times in PBS. After the sections were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 20 min and quenched with 2% H2O2 for 15 min, they were washed three times in PBS. The sections were then incubated in a moist-air chamber at 37°C for 90 min with PANT reaction mixture containing 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20 μg/mL bovine serum albumin, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP at 30 μM each, 29 μM biotinylated dATP, 1 μM dATP, and 40 U/mL Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Sigma) in PBS (pH 7.4). The reaction was terminated by two PBS washes. After washing for 5 min in PBS containing bovine serum albumin (0.5 mg/mL), the slides were incubated for 60 min at 24°C with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain Elite ABC, Burlingame, CA, USA) in PBS containing bovine serum albumin. Detection of the biotin-streptavidin-peroxidase complex was carried out by incubating the sections with a solution of nickel and diaminobenzidine in PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.05% H2O2. To determine non-specific labeling, selected sections were incubated in the reaction buffer without DNA polymerase I. The total numbers of PANT-positive neurons in the entire CA1 regions were counted microscopically by two investigators blind to the experimental conditions.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed using the standard method described previously (Zhang et al. 2006, 2007a). Rats were killed at 1, 4 and 24 h after global ischemia, or 24 h after sham operation (n = 4 per experimental condition). In leptin-treated groups, 6 μg of leptin was infused into the right ICV at 20 min after ischemia. The CA1 region of the hippocampus was separated, homogenized in cell lysis buffer and sonicated, The total protein extracts were subjected to western blot analysis. Blots were probed with antibodies recognizing total-Akt (t-Akt), phosphorylated-Akt (p-Akt) at Ser-473; total-ERK1/2 (t-ERK1/2), phosphorylated-ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) at Thr202/Tyr204; total-STAT3 (t-STAT3) and phosphorylated-STAT3 (p-STAT3) at Tyr705 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); total-CREB (t-CREB, Cell Signaling Technology); and phosphorylated CREB (p-CREB) at Ser-133 (Upstate, Beverly, MA, USA) and BDNF (H-117, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Gel analysis was accomplished with the assistance of a computerized analysis software, MCID (Imaging Research Inc., St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada).

Immunohistochemistry

Rats were killed at 1 h after ischemia, or 1 h after sham operation (n = 3 per experimental condition). In leptin-treated groups, 6 μg of leptin was injected into the right ICV at 20 min following ischemia. Brains were removed and frozen in isopentane cooled with dry ice. 20-μm coronal sections at the level of the dorsal hippocampus were collected and selected for immunohistochemistry staining. The procedures for immunohistochemistry were the same as described elsewhere (Zhang et al. 2006, 2007a). The antibodies (p-Akt and p-ERK) used for immunohistochemistry were the same as those used in western blots as described above. The secondary antibody for p-Akt was conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, and the secondary antibody for p-ERK1/2 was conjugated with Cy3. Hoechst was used for counter-staining. For the assessment of non-specific staining, alternating sections from each experimental condition were incubated without the primary antibody.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean values ± SE. Statistical significance among means was assessed using anova followed by post hoc Scheffe's tests, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Leptin protects hippocampal CA1 neurons against ischemic injury induced by transient global cerebral ischemia in rats

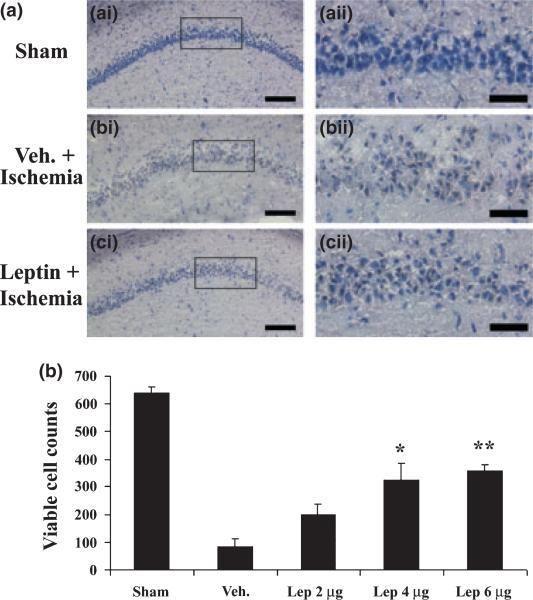

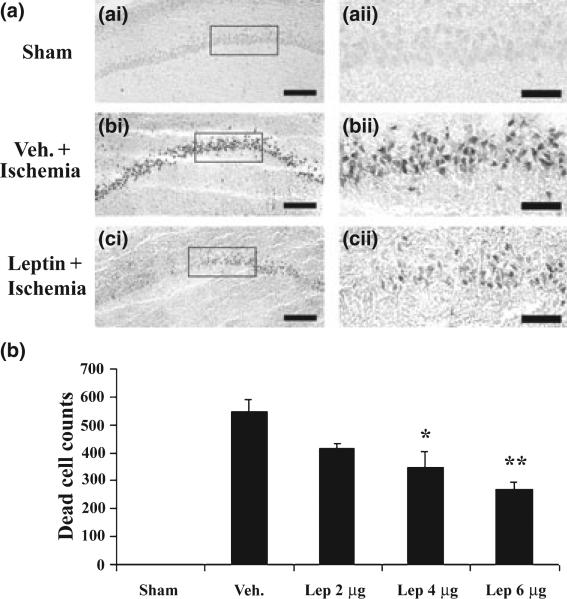

To determine if leptin can protect CA1 neurons against ischemic injury induced by global cerebral ischemia, we injected various amounts of leptin into the ICV of experimental rats. No significant neuroprotection was noticed when 2 μg of leptin was injected. When 4 μg of leptin was injected, there was an increase in viable CA1 neurons (Fig. 1, hematoxylin stain), and a decrease in PANT-positive CA1 neurons (Fig. 2, PANT stain). There was greater neuroprotection when 6 μg of leptin was used (Figs 1 and 2). These data indicate that leptin is neuroprotective against CA1 neuronal injury induced by global cerebral ischemia when a single dose of leptin is administered in 20 min after ischemia and that the neuroprotection is dose-dependent. They also indicate that leptin can offer neuroprotection through its central action alone, as it is administrated locally.

Fig. 1.

Leptin protects hippocampal CA1 neurons against ischemic injury in rats. (a) Representative microphotographs of hematoxylin-stained hippocampal CA1 regions at 72 h after global ischemia in rats. (a-i) sham-operated; (b-i) vehicle-treated ischemia; and (c-i) leptin-treated ischemia. (a-ii), (b-ii), and (c-ii) demonstrate the magnified CA1 neurons whose origins are indicated by the boxes in (a-i), (b-i), and (c-i), respectively. (b) Viable CA1 neurons were counted and presented as cell number per hippocampal section, and the mean numbers were plotted for each group. Sham: sham-operated; Veh.: vehicle-treated ischemia; Lep 2 μg, Lep 4 μg and Lep 6 μg: 2 μg, 4 μg and 6 μg leptin were administered at 20 min after ischemia, respectively. Data are mean ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. **p < 0.01 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. Scale bars = 150 μm in (a-i), (b-i), and (c-i); 100 μm in (a-ii), (b-ii) and (c-ii).

Fig. 2.

Leptin decreases hippocampal CA1 neuronal degeneration following ischemia in rats. (a) Representative microphotographs of PANT-stained hippocampal CA1 regions at 72 h after global ischemia in rats. (a-i) sham-operated; (b-i) vehicle-treated ischemia; and (c-i) leptin-treated ischemia. (a-ii), (b-ii), and (c-ii) demonstrate the magnified CA1 neurons whose origins are indicated by the boxes in (a-i), (b-i), and (c-i), respectively. (b) Dead (PANT-positive) CA1 neurons were counted and presented as cell number per hippocampal section, and the mean numbers were plotted for each group. Sham: sham-operated; Veh.: vehicle-treated ischemia; Lep 2 μg, Lep 4 μg and Lep 6 μg: 2 μg, 4 μg and 6 μg leptin were administered at 20 min after ischemia, respectively. Data are mean ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. **p < 0.01 vs. vehicle-ischemia group. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. Scale bars = 150 μm in (a-i), (b-i), and (c-i); 100 μm in (a-ii), (b-ii) and (c-ii).

Leptin receptors mediate neuroprotection

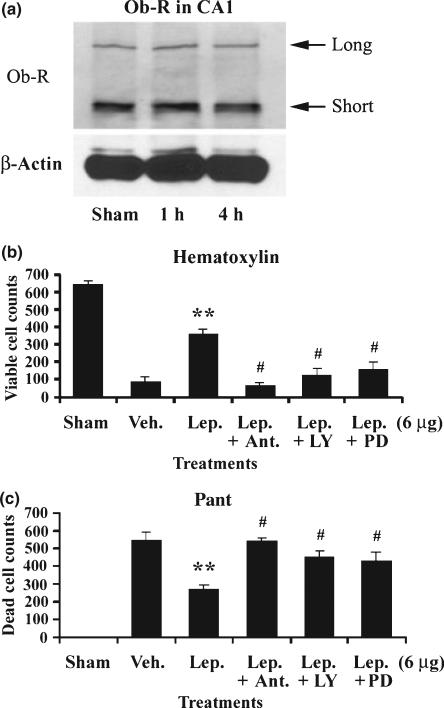

The neuroprotection of leptin is thought to be mediated by leptin receptor, since several downstream signaling pathways of leptin receptors have been activated, and the inhibition of those pathways has been shown to reduce the protective effects of leptin (Russo et al. 2004; Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007b; Diano and Horvath 2008; Guo et al. 2008). To detect if this is the case in our particular model, we first determined whether leptin receptors are expressed in hippocampal CA1 neurons. As shown in Fig. 3(a), leptin receptors were expressed in CA1 regions in sham-operated rat, and the receptor levels were maintained after global ischemia, indicating that rapid degradation of leptin receptors does not occurs shortly after induction of ischemia. We then used a unique rat leptin antagonist to determine whether it exerts a blocking effect capable of attenuating the neuroprotective effects of leptin. This leptin antagonist, containing three mutations (L39A/D40A/F41A), can bind leptin receptors with an affinity similar to that of leptin but does not exert any agonist effect (Gertler 2006; Zhang et al. 2007c). We first injected 12 μg of rat leptin antagonist into ICV 10 min before inducing global ischemia, and then injected 6 μg of leptin at 20 min after ischemia. Three days later, rat brains were removed, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and PANT. As shown in Fig. 3(b), leptin antagonist entirely eradicated the neuroprotection of leptin, indicating that the neuroprotection of leptin is mediated by leptin receptors.

Fig. 3.

The neuroprotection of leptin is mediated by leptin receptor. (a) Both the short and long isoforms of the leptin receptor (Ob-R) were expressed in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Sham: sham-operated group; 1 h and 4 h, one and four hours after global ischemia, respectively. (b) Leptin antagonist, LY294002 and PD98059 abolished the pro-survival role of leptin. Viable CA1 neurons were counted, and the mean numbers were plotted for each group. Sham: sham-operated; Veh.: vehicle-treated ischemia; Lep.: 6 μg leptin was injected into ICV at 20 min after global ischemia; Ant.: Leptin antagonist was injected into ICV 10 min before global ischemia; LY: LY294002 was injected into ICV 10 min before global ischemia; PD: PD98059 was injected into ICV 10 min before global ischemia. Data are mean ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. **p < 0.01 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. #p < 0.05 vs. leptin-treated group and p > 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. (c) Leptin antagonist, LY294002 and PD98059 abolished the anti-apoptotic role of leptin. Dead (PANT positive) CA1 neurons were counted, and the mean number was plotted for each group. Sham: Sham-operated; Veh.: Vehicle-treated ischemia; Lep.: 6 μg leptin was injected into ICV at 20 min after global ischemia; Ant.: Leptin antagonist was injected into ICV 10 min before global ischemia; LY: LY294002 was injected into ICV 10 min before global ischemia; PD: PD98059 was injected into ICV 10 min before global ischemia. Data are mean ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. **p < 0.01 vs. ischemia group. #p < 0.05 vs. leptin-treated group and p > 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group.

Akt signaling pathway plays a critical role in leptin-mediated neuroprotection

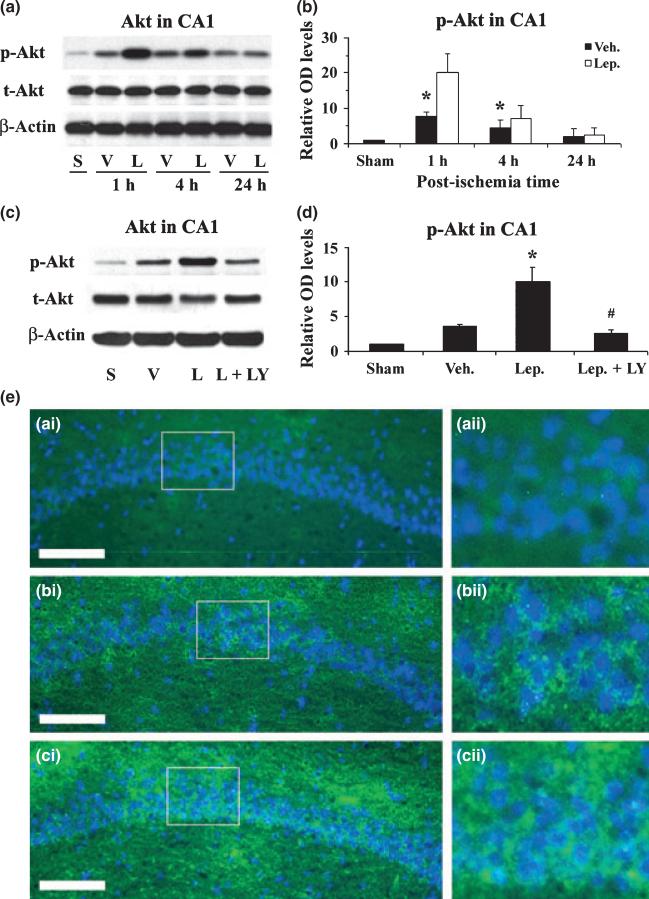

The downstream signaling cascades of leptin receptor activation include the Janus-tyrosine kinase 2-STAT3, ERK1/2, and PI3K-Akt pathways (Bates and Myers 2003). Because Akt is a master protein kinase that promotes neuronal survival after brain ischemia (Zhang et al. 2004), we therefore hypothesize that the Akt pathway may be important in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against CA1 neuronal injury induced by global cerebral ischemia in rats. To prove our hypothesis, we first detected the phosphorylation of Akt in hippocampal CA1 tissues at 1, 4 and 24 h after global ischemia. At 1 and 4 h after ischemia, there was an increase in the phosphorylation of Akt in vehicle-treated groups; this effect was further enhanced by leptin (Fig. 4a, b and e). To confirm the protective role of Akt, we performed Akt inhibition experiment by injecting LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor, into ICV 10 min before ischemia, and detecting its effects on the phosphorylation of Akt and the neuroprotection of leptin against ischemia. As shown in Fig. 4, LY294002 significantly reduced the phosphorylation of Akt, which consequently blocked the neuroprotective effect of leptin (Fig. 3b and c), indicating that Akt plays a critical role in the leptin-mediated neuroprotection against CA1 neuronal injury induced by transient global cerebral ischemia in rats.

Fig. 4.

Leptin enhances the phosphorylation of Akt in hippocampal CA1 after ischemia. (a) Representative western blots showing the levels of p- and t-Akt in the CA1 region at serial time points following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; and L: Leptin-treated ischemia. (b) The average levels of p-Akt in the CA1 region were increased in the leptin-treated ischemia group at 1 h and 4 h following global ischemia. Data are presented as means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group at the same time point. (c) Representative western blots showing p- and t-Akt levels in the CA1 region at 1 h following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; L: leptin-treated ischemia; and L+LY: leptin and LY294002-treated ischemia group. (d) The average levels of p-Akt in the CA1 region were quantified and showed an increase in the leptin-treated group at 1 h following global ischemia, which was abolished by the co-administration of LY294002. Sham: sham-operated; Veh.: vehicle-treated ischemia; Lep.: leptin-treated ischemia; and Lep+LY: leptin and LY294002-treated ischemia group. Data are means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group, #p < 0.05 vs. leptin-treated ischemia group, > 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. (e) Representative photomicrographs of immunofluorescent stained p-Akt in the CA1 regions 1 h after global ischemia. p-Akt is primarily neuron-distributed and shown in green; and nuclei are counter-stained blue by Hoechst. (a-i) sham-operated; (b-i) vehicle-treated ischemia; and (c-i) leptin-treated ischemia. (a-ii), (b-ii) and (c-ii) demonstrate the magnified CA1 neurons whose origins are indicated by the boxes in (a-i), (b-i), and (c-i), respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm.

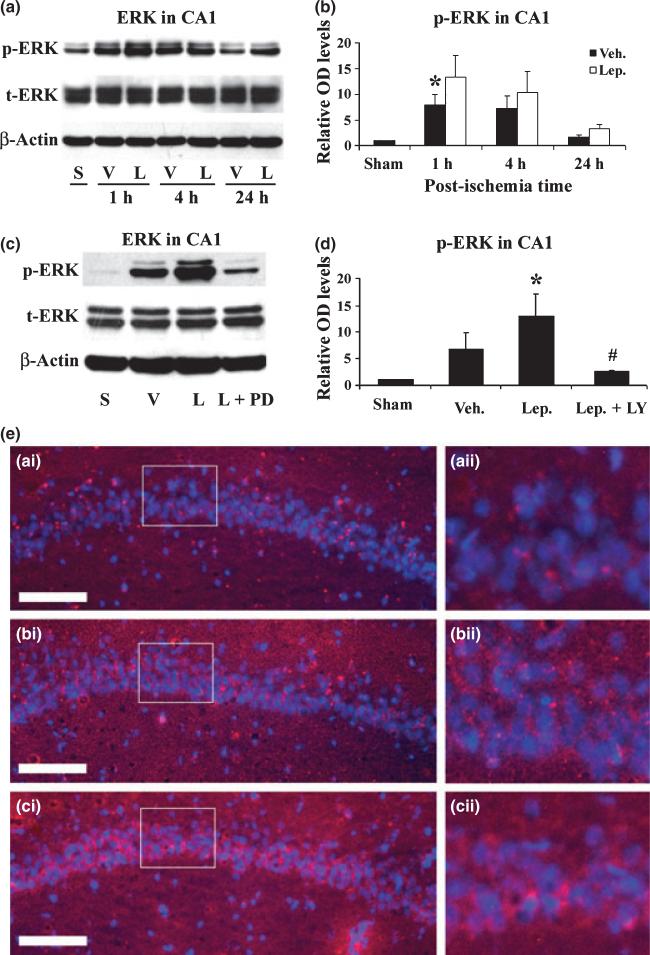

ERK1/2 signaling pathway plays an important role in leptin-mediated neuroprotection

We previously reported that the ERK1/2 signaling pathway plays a key role in the neuroprotective effect of leptin against injuries induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation, focal cerebral ischemia, and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) (Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007b). To detect the role of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CA1 regions after global ischemia in rats, we performed western blots and immunofluorescent stains. As shown in Fig. 5(a), (b) and (e), an increase in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was noticed at 1 h in vehicle-treated rats, and this was significantly enhanced by the leptin. To confirm the role of ERK1/2, we subsequently performed ERK1/2 inhibition experiment by injecting PD98059, a MAPK inhibitor, into ICV before ischemia. As shown in Fig. 5(c) and (d), PD98059 significantly reduced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, thereby blocking the neuroprotective effect of leptin (Fig. 3b and c), indicating that ERK1/2 activation plays an important role in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against CA1 neuronal injury.

Fig. 5.

Leptin enhances the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in hippocampal CA1 after ischemia. (a) Representative western blots showing the levels of p- and t-ERK1/2 in the CA1 region at serial time points following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; and L: leptin-treated ischemia. (b) The average levels of p-ERK1/2 in the CA1 region were increased in the leptin-treated ischemia group at 1 h and 4 h following global ischemia. Data are presented as means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group at the same time point. (c) Representative western blots showing p- and t-ERK1/2 levels in the CA1 region at 1 h following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; L: leptin-treated ischemia; and L+PD: leptin and PD98059-treated ischemia group. (d) The average levels of p-ERK in the CA1 region were quantified and showed an increase in the leptin-treated group at 1 h following global ischemia, which was abolished by the co-administration of PD98059. Sham: sham-operated; Veh.: vehicle-treated ischemia; Lep.: leptin-treated ischemia; and Lep+PD: leptin and PD98059-treated ischemia group. Data are means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group, #p < 0.05 vs. leptin-treated ischemia group, > 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group. (e) Representative photomicrographs of immunofluorescent stained p-ERk1/2 in the CA1 regions 1 h after global ischemia. p-ERK1/2 is primarily neuron-distributed and shown in red; and nuclei are counter-stained blue by Hoechst. (a-i) sham-operated; (b-i) vehicle-treated ischemia; and (c-i) leptin-treated ischemia. (a-ii), (b-ii) and (c-ii) demonstrate the magnified CA1 neurons whose origins are indicated by the boxes in (a-i), (b-i), and (c-i), respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm.

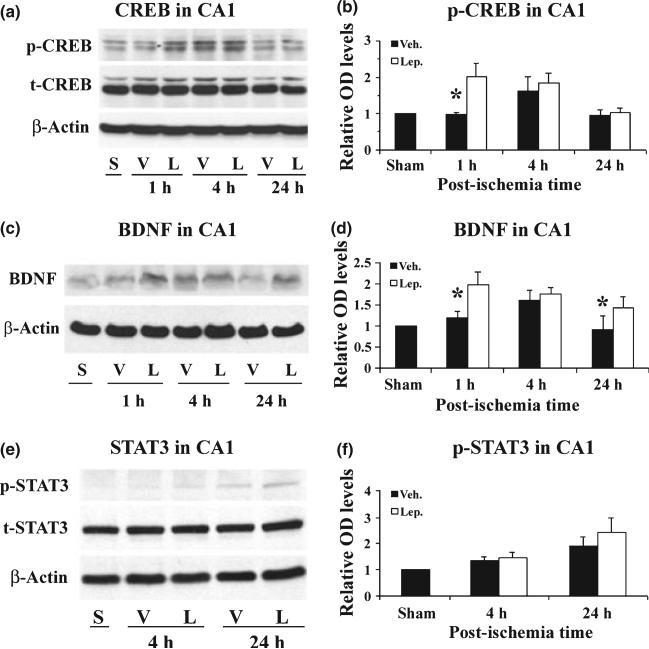

Leptin increases CREB phosphorylation and up-regulates BDNF expression in the CA1 region after global ischemia

It has been previously demonstrated that an increase in CREB phosphorylation and an up-regulation of BDNF are essential to the neuroprotective role of leptin against neuronal injury induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation, focal brain ischemia as well as 6-OHDA (Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007b). To determine whether CREB and BDNF are also involved in leptin-mediated neuroprotection in the rat global ischemia model, we performed western blots using the same protein samples as previously described. As shown in Fig. 6(a) and (b), there was a significant increase in p-CREB in the leptin-treated group at 1 h post-ischemia, maintained at 4 h, when compared to the sham-operated group. The level of p-CREB did not increase in the vehicle-treated group at 1 h post-ischemia and only attained level comparable to that of the leptin-treated group at 4 h after ischemia. Parallel to the change in p-CREB, an increased expression of BDNF was noticed in the leptin-treated group (Fig. 6c and d). These data suggest that the enhancement of CREB phosphorylation and the up-regulation of BDNF contribute to the neuroprotection of leptin against ischemic injury induced by transient global brain ischemia in rats.

Fig. 6.

Leptin increases the phosphorylation of CREB and up-regulates BDNF expression in the hippocampal CA1 region following global ischemia. (a) Representative western blots showing the levels of p- and CREB in the CA1 region at serial time points following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; and L: leptin-treated ischemia. (b) The average levels of p-CREB in the CA1 region were increased in the leptin-treated ischemia group at 1 h following global ischemia. Data are presented as means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. *p < 0.05 vs. vehicle-treated ischemia group at the same time point. (c) Representative western blots showing the levels of mature form BDNF in the CA1 region at serial time points following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; and L: leptin-treated ischemia. (d) The average levels of BDNF in the CA1 region were quantified from western blots. BDNF was increased in the leptin-treated group 1 h and 24 h following global ischemia. Data are means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests. *p < 0.05 vs. control group at the same time point. (e) Representative western blots showing the levels of p- and t-STAT3 in the CA1 region at serial time points following ischemia. S: sham-operated; V: vehicle-treated ischemia; and L: leptin-treated ischemia. (b) The average levels of p-STAT3 in the CA1 region were not significantly increased in the leptin-treated ischemia group following global ischemia. Data are means ± SEM, assessed by anova and post hoc Scheffe's tests.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is another downstream signaling pathway of leptin receptors, and it may play a role in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against seizure and ischemia in focal ischemia (Zhang et al. 2007b; Guo et al. 2008). Although we noticed a trend of increase in p-STAT3 in the leptin-treated group at 24 h after ischemia, the difference between the vehicle- and leptin-treated groups was not significant (Fig. 6e and f), suggesting that STAT3 plays a less important role in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against global ischemia in rats.

Discussion

Our present data demonstrate that a single dose of leptin infused into ICV attenuates hippocampal CA1 neuronal death induced by transient global cerebral ischemia in rats. The neuroprotection of leptin is mediated by leptin receptors, as leptin antagonist blocks the neuroprotective effects of leptin. Moreover, the Akt and ERK 1/2 signaling pathways play critical roles in leptin-mediated neuroprotection.

In addition to its defined functions in regulating food intake and energy balance, leptin has been recently established as a neuroprotective agent against models of acute and chronic neurological disorders. For example, leptin reduces the infarct volume induced by focal cerebral ischemia in mice (Zhang et al. 2007b), protects hippocampal neurons against cell death induced by epilepsy (Diano and Horvath 2008; Guo et al. 2008), and prevents 6-OHDA-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in a model of Parkinson's disease (Weng et al. 2007). The data presented here extend the observed neuroprotective effects of leptin to the prevention of hippocampal CA1 neuronal death induced by transient global cerebral ischemia. Furthermore, our current data also show that leptin can provide neuroprotection through central action alone by direct binding to leptin receptor on neurons.

The neuroprotective mechanisms of leptin involve ERK1/2 (Russo et al. 2004; Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007b), Akt (Russo et al. 2004) and STAT3 signaling pathways (Guo et al. 2008), which are all downstream signaling events of leptin receptor activation. Inhibition of individual routes of downstream signaling pathways compromises the neuroprotective effects of leptin, suggesting that these pathways are essential to the neuroprotective role of leptin. However, these findings alone are not sufficient to demonstrate that neuroprotection of leptin is mediated by leptin receptors as other hormones may utilize these same downstream pathways as well. It would be preferable to utilize an animal model with a full deficiency of leptin receptors; however, this model does not exist. Alternatively, a leptin antagonist, which has been introduced recently (Gertler 2006), can compete with leptin for binding leptin receptors and are effective in inhibiting leptin-related biofunctions. Using this rat leptin-receptor antagonist, we found that the neuroprotective effects of leptin are completely abolished, indicating that leptin neuroprotection is indeed mediated by leptin receptors.

Akt has been recognized as a master protein kinase that promotes neuronal survival (Yano et al. 2001; Franke et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2004). It is especially important in neuroprotective effects mediated by erythropoietin (Siren et al. 2001; Zhang et al. 2006) and BDNF (Ferrer et al. 1998; Kiprianova et al. 1999) against ischemic CA1 neuronal injury. We demonstrate here that leptin also enhances the phosphorylation of Akt in hippocampal CA1, and that the PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 abolishes the neuroprotective effects of leptin. Therefore, Akt plays an essential role in the neuroprotective effects of leptin against ischemic CA1 neuronal death (Russo et al. 2004; Guo et al. 2008).

In our previous reports, we demonstrated that the ERK1/2 signaling pathway plays a critical role in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against neuronal death induced by focal cerebral ischemia or the dopaminergic neurotoxin 6-OHDA (Weng et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007b). The neuroprotective ERK1/2 signaling may involve both direct inhibition of cell death machinery and transcriptional regulation of cell death/survival factors. For instance, ERK-1/2 can phosphorylate Bad at Ser-112 (Bonni et al. 1999; Fujimura et al. 1999; Jin et al. 2002), thus inhibiting its apoptotic activity; ERK-1/2 can phosphorylate Bim-EL at Ser-69, facilitating its degradation (Weston et al. 2003; Harada et al. 2004); and ERK-1/2 can also phosphorylate caspase-9 at Thr-125, blocking its cleavage and activation (Allan et al. 2003). Furthermore, ERK-1/2 can also phosphorylate and activate several transcription factors such as CREB, and then up-regulate BDNF (Xing et al. 1996; Weng et al. 2007). The current data further support the critical role of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against ischemic injury.

In previous reports, STAT3 in hippocampal CA1 was phosphorylated as early as 4 h after transient global cerebral ischemia in rat, and this became more obvious 24 h after ischemia and phosphorylated STAT3 was predominantly localized to astrocytes (Choi et al. 2003). We observed a similar phosphorylation pattern of STAT3 in CA1 after global brain ischemia in the current study. However, no significant enhancement of STAT3 phosphorylation was observed in leptin-treated rats, suggesting that STAT3 may not be essential in leptin-mediated neuroprotection against ischemic CA1 neuronal death.

In summary, leptin attenuates hippocampal CA1 neuronal injury induced by transient global cerebral ischemia in rats, which represents an animal model of cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation in humans. Our results, along with previous studies demonstrating leptin-mediated neuroprotection against ischemia as well as Parkinson's disease and epilepsy, suggest that leptin is a promising therapeutic agent that potentially can be used to treat both acute and chronic neurological disorders.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants NS43802, NS45048, NS36736, NS 56118 and a VA Merit Review grant. We thank Carol Culver and Aalap C. Shan for editorial assistance and Pat Strickler for secretarial support.

Abbreviations used

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CREB

cyclic AMP response element-binding protein

- ERK

extracellular signal-related kinase

- ICV

intracerebral ventricle

- PANT

DNA polymerase I-mediated biotin-dATP nick-translation

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3 kinase

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

References

- Ahima RS. Central actions of adipocyte hormones. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;16:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan LA, Morrice N, Brady S, Magee G, Pathak S, Clarke PR. Inhibition of caspase-9 through phosphorylation at Thr 125 by ERK MAPK. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:647–654. doi: 10.1038/ncb1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almog B, Gold R, Tajima K, et al. Leptin attenuates follicular apoptosis and accelerates the onset of puberty in immature rats. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2001;183:179–191. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks AS, Davis SM, Bates SH, Myers MG., Jr Activation of downstream signals by the long form of the leptin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14563–14572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SH, Myers MG., Jr The role of leptin receptor signaling in feeding and neuroendocrine function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;14:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SH, Stearns WH, Dundon TA, et al. STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature. 2003;421:856–859. doi: 10.1038/nature01388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher S, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in reproduction. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2007;14:458–464. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f1cfdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Brunet A, West AE, Datta SR, Takasu MA, Greenberg ME. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1358–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Nagayama T, Jin K, Stetler RA, Zhu RL, Graham SH, Simon RP. Induction of caspase-3-like protease may mediate delayed neuronal death in the hippocampus after transient cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:4914–4928. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04914.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Kim SY, Cha JH, et al. Upregulation of gp130 and STAT3 activation in the rat hippocampus following transient forebrain ischemia. Glia. 2003;41:237–246. doi: 10.1002/glia.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diano S, Horvath TL. Anticonvulsant effects of leptin in epilepsy. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:26–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI34511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Ballabriga J, Marti E, Perez E, Alberch J, Arenas E. BDNF up-regulates TrkB protein and prevents the death of CA1 neurons following transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:253–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuno A, Rodriguez A, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Muniz P, Salvador J, Diez J, Fruhbeck G. Leptin inhibits angiotensin II-induced intracellular calcium increase and vasoconstriction in the rat aorta. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3555–3560. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Hornik CP, Segev L, Shostak GA, Sugimoto C. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: size matters. Oncogene. 2003;22:8983–8998. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Kawase M, Copin JC, Calagui B, Epstein CJ, Chan PH. Manganese superoxide dismutase mediates the early release of mitochondrial cytochrome C and subsequent DNA fragmentation after permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:3414–3422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03414.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertler A. Development of leptin antagonists and their potential use in experimental biology and medicine. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;17:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Jiang H, Xu X, Duan W, Mattson MP. Leptin-mediated cell survival signaling in hippocampal neurons mediated by JAK STAT3 and mitochondrial stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1754–1763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Quearry B, Ruiz-Vela A, Korsmeyer SJ. Survival factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylates BIM, inhibiting its association with BAX and proapoptotic activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15313–15317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406837101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi K, Fulop K, Kovacs K, Toth S, Falus A. Leptin-induced signal transduction pathways. Cell Biol. Int. 2004;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imada K, Leonard WJ. The Jak-STAT pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2000;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Mao XO, Zhu Y, Greenberg DA. MEK and ERK protect hypoxic cortical neurons via phosphorylation of Bad. J. Neurochem. 2002;80:119–125. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiprianova I, Freiman TM, Desiderato S, Schwab S, Galmbacher R, Gillardon F, Spranger M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents neuronal death and glial activation after global ischemia in the rat. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;56:21–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<21::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloek C, Haq AK, Dunn SL, Lavery HJ, Banks AS, Myers MG., Jr Regulation of Jak kinases by intracellular leptin receptor sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41547–41555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo G, Vecchione C, Fratta L, Marino G, Trimarco V, d'Amati G, Trimarco B. Leptin induces direct vasodilation through distinct endothelial mechanisms. Diabetes. 2000;49:293–297. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer JG, Hoggard N, Williams LM, Lawrence CB, Hannah LT, Trayhurn P. Localization of leptin receptor mRNA and the long form splice variant (Ob-Rb) in mouse hypothalamus and adjacent brain regions by in situ hybridization. FEBS Lett. 1996;387:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama T, Lan J, Henshall DC, Chen D, O'Horo C, Simon RP, Chen J. Induction of oxidative DNA damage in the peri-infarct region after permanent focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:1716–1728. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB, Plum F. Temporal profile of neuronal damage in a model of transient forebrain ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 1982;11:491–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo VC, Metaxas S, Kobayashi K, Harris M, Werther GA. Antiapoptotic effects of leptin in human neuroblastoma cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4103–4112. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Hattori H, Sasaki T, Gotoh J, Hamada J, Fukuuchi Y. Activation of caspase-12 by endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Neuroscience. 2003;118:491–499. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00910-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siren AL, Fratelli M, Brines M, et al. Erythropoietin prevents neuronal apoptosis after cerebral ischemia and metabolic stress. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4044–4049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051606598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng Z, Signore AP, Gao Y, Wang S, Zhang F, Hastings T, Yin XM, Chen J. Leptin protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced dopaminergic cell death via mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34479–34491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston CR, Balmanno K, Chalmers C, Hadfield K, Molton SA, Ley R, Wagner EF, Cook SJ. Activation of ERK1/2 by deltaRaf-1:ER* represses Bim expression independently of the JNK or PI3K pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:1281–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Coupling of the RAS-MAPK pathway to gene activation by RSK2, a growth factor-regulated CREB kinase. Science. 1996;273:959–963. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano S, Morioka M, Fukunaga K, Kawano T, Hara T, Kai Y, Hamada J, Miyamoto E, Ushio Y. Activation of Akt/protein kinase B contributes to induction of ischemic tolerance in the CA1 subfield of gerbil hippocampus. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:351–360. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Yin W, Chen J. Apoptosis in cerebral ischemia: executional and regulatory signaling mechanisms. Neurol. Res. 2004;26:835–845. doi: 10.1179/016164104X3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Signore AP, Zhou Z, Wang S, Cao G, Chen J. Erythropoietin protects CA1 neurons against global cerebral ischemia in rat: potential signaling mechanisms. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006;83:1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wang S, Cao G, Gao Y, Chen J. Signal transducers and activators of transcription 5 contributes to erythropoietin-mediated neuroprotection against hippocampal neuronal death after transient global cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007a;25:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Wang S, Signore AP, Chen J. Neuroprotective effects of leptin against ischemic injury induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation and transient cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2007b;38:2329–2336. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.482786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Matheny MK, Tumer N, Mitchell MK, Scarpace PJ. Leptin antagonist reveals that the normalization of caloric intake and the thermic effect of food after high-fat feeding are leptin dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007c;292:R868–R874. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00213.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]