Abstract

Objective

The aims of this study were to investigate the body fat distribution pattern in prepubertal Chinese children and to investigate the relationship between central fat distribution and specific biomarkers of cardiovascular disease.

Research Methods and Procedures

The study was conducted in an urban Mainland Chinese (Jinan, Shandong) sample of children using a cross-sectional design. Pubertal status was determined by Tanner criteria. Measurements included weight, height, waist circumference, DXA measures of total body fat and trunk fat; fasting serum measures of glucose, insulin, triglyceride, cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Multiple regression models were developed with the biomarkers of cardiovascular risk factor as the dependent variables, and adjustments were made for significant covariates, including sex, age, height, weight, waist circumference, total body fat, trunk fat, and interactions.

Results

A total of 247 healthy prepubertal subjects were studied. After co-varying for age, weight, height, and extremity fat (the sum of arm fat and leg fat), girls had greater trunk fat than boys (p < 0.0001, R2 for model = 0.95). Insulin and triglyceride were positively related to central fat measured by DXA-trunk fat (p < 0.05) but not related to the waist circumference. In the blood pressure model, waist circumference was a significant predictor of both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, while DXA-trunk fat was associated with diastolic blood pressure only. Significant interactions between sex and trunk fat, and sex and total fat, were found in relation to diastolic blood pressure.

Discussion

In prepubertal Chinese children, greater trunk fat was significantly associated with higher insulin and triglyceride in boys and girls and was associated with higher diastolic blood pressure in boys only.

Keywords: fat distribution, cardiovascular risk factors, prepubertal, Chinese

Introduction

Truncal or central body fat distribution, a characteristic of adult males that emerges during puberty, is recognized as a cardiovascular risk factor in both adults (1– 4) and children (5– 8). As the prevalence of overweight/obesity is increasing among children in developing countries including China (9), it is important from the perspective of public health prevention to investigate fat distribution and its relationship to potential metabolic consequences in children. Studies to date conducted in Chinese children have used indirect anthropometric measures, including the waist-to-hip ratio or skinfold thickness (9,10), as indices of fat distribution. Besides numerous problems associated with the use of ratios from a statistical analysis perspective (11), the waist-to-hip ratio has been challenged as a valid assessment of fat distribution in children (12) as it reflects bone-related hip circumference as much as fat. DXA has been shown to provide an accurate and precise measure of lean body mass and total fat mass (13,14) and has been validated against a range of established techniques, including underwater weighing (15,16). DXA studies in children have also been used to assess fat distribution including android vs. gynoid (5) and central vs. peripheral (17) patterns.

The aims of this study were to investigate the body fat distribution pattern in prepubertal Chinese children and to investigate the relationship between fat distribution and specific biomarkers of cardiovascular disease.

Research Methods and Procedures

Subjects

One of our study aims was to see whether sex differences in body fat distribution exist in Chinese children before puberty as defined by Tanner criteria. Using this young age group may reduce the relatively large contribution of lifestyle factors that cumulatively influence the association between fat distribution and cardiovascular risk factors in older subjects. Subjects between 3 and 11 years of age were recruited through local schools or children of hospital employees. After physical examination, only prepubertal children were included in the study. There was no weight or height limitation to enrollment in this study. Inclusion criteria required that participants be healthy and without any diagnosed medical condition that could potentially affect the variables under investigation. Consent was obtained from each volunteer’s parent or guardian, and assent was obtained from each volunteer as well. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital (SLRHC)1 and by the Institutional Review Board of Jinan Maternity and Childcare Hospital (JMCH).

Measures

All measurements were conducted at JMCH. A pediatrician (X.Z.) from JMCH received training in the Body Composition Unit of SLRHC in the methods used for data collection before initiation of the study. Data collection began in August 2003 and data went to SLRHC for analysis in May 2004.

Anthropometrics

A physical examination was performed including body weight, height, blood pressure (BP), and pubertal staging. Based on the criteria of Tanner (18), only prepubertal children were included in this study, which means breast Stage 1 and pubic hair Stage 1 for female subjects; and genital Stage 1 and pubic hair Stage 1 for male subjects. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg (XiHeng; Wuxi Weigher Factory, Wuxi City, China) and height to the nearest 0.5 cm using a stadiometer (Butterfly; Shanghai Drawing Stationery Factory, Shanghai, China). Waist circumference was measured at the level of the tip of the lowermost rib (19) to the nearest 0.1 cm. BP was measured three times on the right arm, and an averaged value was used in the analysis. All BP data were obtained with subjects in the seated position using a mercury sphygmomanometer and an appropriate sized cuff. The onset of the fourth Korotkoff sound was used to determine diastolic BP (DBP) in this study (20).

DXA

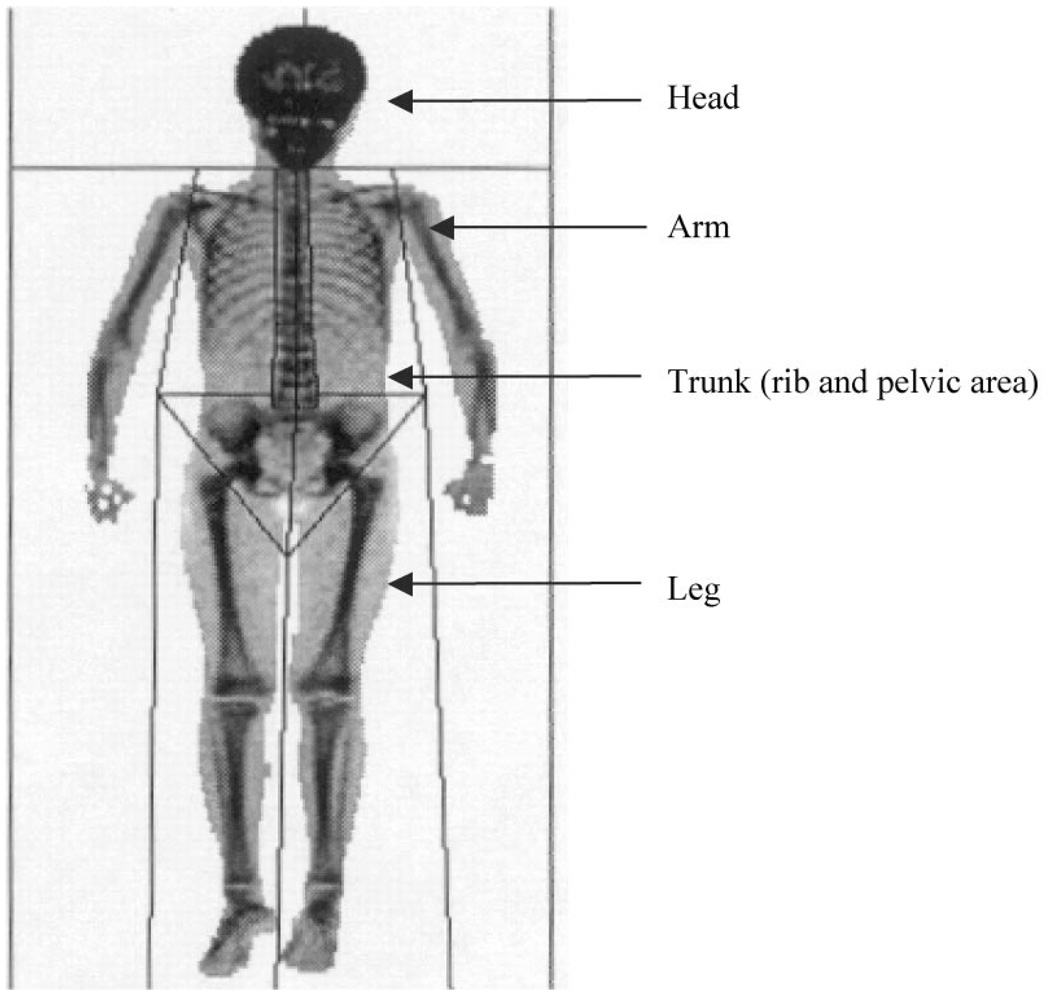

Total body fat and total body fat-free mass were measured with a whole-body DXA scanner (Prodigy, GE Lunar Corp., Madison, WI) using pediatric software version 4.0. The DXA regions are shown in Figure 1, and the calculation of regional soft tissue mass has been previously described (21). During the study setup phase, ethanol and water bottles (8-L volume, Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), simulating fat and fat-free soft tissues, respectively, were scanned as soft-tissue quality control markers three times per day for 7 consecutive days in JMCH. These data were sent to the Body Composition Unit at SLRHC for quality control verification, and these data also served as a reference for the stability of the machine. The soft-tissue quality control was performed weekly (when no subject was studied) and each day that a subject was studied. The coefficient of variation over the study period was 4.6% and 3.1% for ethanol and water, respectively.

Figure 1.

DXA regions (head, arms, trunk, and legs). Trunk region includes both rib and pelvic area. Extremity fat was defined as the sum of leg fat and arm fat.

The reproducibility of DXA in children has been reported (22). Because of concerns surrounding unnecessary radiation exposure in healthy children, scan reproducibility in children was not performed in this study. All DXA data were sent to SLRHC and analyzed by a single technician in the Body Composition Unit.

Fasting Blood Sample

A fasting blood sample was obtained for each study subject from which serum glucose, triglyceride, cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol were measured at the JMCH laboratory using reagents provided by DIALAB (Vienna, Austria); and serum insulin level was measured in duplicate by using radioimmunoassay (Diagnostics Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA) (intra-assay coefficient of variation = 3.1% to 9.3%; inter-assay coefficient of variation = 4.9% to 10.0%) at the Gynecologic Endocrinology and Women Health Center, Peking Union Medical Collage Hospital, Beijing, China.

Statistical Analysis

Student t test was used to compare the group means of specific variables between sexes. The international cut-off points (23) for obesity between 2 and 18 years of age was used to define overweight status in this sample.

To study sex difference on body fat distribution, we used an analysis of covariance with DXA trunk fat as the dependent variable and extremity fat (the sum of leg fat and arm fat), age, weight, and height as covariates. This approach was chosen to avoid the numerous problems associated with the use of ratios in statistical analysis.

The second aim of the study was to investigate the association between central fat, either the anthropometric measure of waist circumference or the DXA measure of trunk fat, and metabolic parameters, after controlling for known confounders. All models included age, sex, body size (weight and height or total fat and height), central fat index (either waist or trunk fat), and interactions. The independent variable with the largest p values was removed in a stepwise backward elimination procedure until all variables remaining in the model were statistically significant or until the central fat index was the next variable to be removed due to its large p value.

Normality of the residuals of the regression model was checked. When the residuals were not normally distributed, data transformation (log) was first made on the dependent variable, and secondly on one of the independent variables to achieve normality. The transformed variables were indicated in Table 1 toTable 3.

Table 1.

Multiple regression analysis with trunk fat (log-transformed) as the dependent variable

| Coefficients (standard error) |

P | Model R2 | Model p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −5.25 (0.31) | <0.0001 | 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| Extremity fat* | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.11 | ||

| Age (yrs) | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.31 | ||

| Sex (boys = 1, girls = 0) | −0.24 (0.03) | <0.0001 | ||

| Weight (cm) (log-transformed) | 2.66 (0.17) | <0.0001 | ||

| Height (cm) | −0.02 (0.00) | <0.0001 |

Extremity fat was defined as the sum of leg fat and arm fat from the DXA measure.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis with insulin, triglyceride, and blood pressure as the dependent variables with DXA-measured trunk fat as the central fat index*

| β | P | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin (log-transformed) | |||

| Intercept | 1.56 | 0.01 | 0.44 |

| Trunk fat (log-transformed) | 0.28 | 0.01 | |

| Total fat | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Triglyceride (log-transformed) | |||

| Intercept | −0.25 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Trunk fat | 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||

| Intercept | 56.44 | 0.01 | 0.45 |

| Sex (boy = 1, girl = 0) | 20.62 | 0.06 | |

| Trunk fat | −3.37 | 0.11 | |

| Total fat | 2.46 | 0.02 | |

| Height (cm) | 0.29 | 0.01 | |

| Interaction (sex × height) | −0.15 | 0.09 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||

| Intercept | 36.39 | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| Sex (boy = 1, girl = 0) | 4.02 | 0.01 | |

| Trunk fat | −7.92 | 0.03 | |

| Total fat | 4.33 | 0.01 | |

| Height (cm) | 0.16 | 0.01 | |

| Interaction (sex × trunk fat) | 9.03 | 0.02 | |

| Interaction (sex × total fat) | −4.59 | 0.01 |

The initial model included age, sex, waist, weight, height, and interactions between sex and waist, sex and weight, and sex and height The independent variable with the largest p value was removed in a stepwise backward elimination procedure until all variables remaining in the model were statistically significant (p < 0.05) or until the central fat index was the next variable to be removed.

Some covariates in the regression analyses are highly correlated, such as trunk fat and total fat, and colinearity effects are likely in the regression models. Our interest in these variables was only as covariates so that their effects on trunk fat could be removed. Therefore, only the statistically significant beta coefficients were mentioned in the Results and were interpreted in the Discussion section. A p < 0.05 value was set as the level for statistical significance. All statistics were computed using SAS software, version 8 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) (24).

Results

Subject Characteristics

A total of 148 healthy prepubertal boys (age range, 3 to 11 years) and 99 girls (age range, 3 to 10 years) were studied. The mean and standard deviation values for age, height, weight, waist, and DXA body fat are presented by sex in Table 4. Except for percentage body fat, significant sex differences were found in the group means for all other variables (p < 0.01). The international cut-off points (23) for BMI for obesity by sex between 2 and 18 years, defined to pass through BMI of 30 at age 18, obtained by averaging data from Brazil, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Netherlands, Singapore, and United States, were used to calculate the obesity rate in this study; 23% of boys (34 of 148) and 14% of girls (14 of 99) were obese based on the international cut-off points for sex and age (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subject characteristics and the number of total and obese subjects in each age and sex group†

| Subject characteristics | Boys (n = 148) (mean ± SD) |

Girls (n = 99) (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs)* | 7.1 ± 2.2 | 6.0 ± 1.9 |

| Weight (kg)* | 32.5 ± 13.5 | 25.0 ± 8.2 |

| Height (cm)* | 128.8 ± 14.4 | 120.5 ± 13.7 |

| Waist (cm)* | 60.1 ± 12.1 | 54.0 ± 6.9 |

| Trunk fat-DXA (kg)* | 4.6 ± 4.0 | 3.1 ± 2.3 |

| Total fat-DXA (kg)* | 9.6 ± 8.2 | 6.7 ± 4.8 |

| % body fat | 25.8 ± 12.3 | 25.2 ± 9.4 |

| Age | Boys [total (obese)] | Girls [total (obese)] |

| 3 yrs | 8 (1) | 11 (0) |

| 4 yrs | 14 (4) | 17 (4) |

| 5 yrs | 19 (1) | 11 (2) |

| 6 yrs | 17 (2) | 21 (2) |

| 7 yrs | 24 (3) | 16 (2) |

| 8 yrs | 21 (8) | 12 (3) |

| 9 yrs | 17 (9) | 7 (1) |

| 10 yrs | 22 (4) | 4 (0) |

| 11 yrs | 6 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Total sample | 148 (34) | 99 (14) |

SD, standard deviation.

Significant sex difference (p < 0.05) from t test.

The international cut-off points for obesity between 2 and 18 years of age were used to define obesity in the sample (23). Each age-sex cell presents the total number of subjects and the number of obese subjects (in parentheses).

Body Fat and Its Distribution

Body fat distribution was studied using a regression model with trunk fat as the dependent variable and extremity fat (the sum of arm fat and leg fat) as a covariate (Table 1). After co-varying for age (p > 0.05), weight (p < 0.0001), height (p < 0.0001), and extremity fat (p > 0.05), girls had more trunk fat than boys (p < 0.0001, R2 for model = 0.95).

Central Fat Distribution and Certain Potential Cardiovascular Risk Factors

General linear models were used to examine the associations between central fat distribution and specific biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: glucose, insulin, triglyceride, cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and BP. Central fat was measured by either waist circumference or DXA trunk fat. No statistically significant associations were found between central fat and glucose, cholesterol, and HDL-cholesterol (results not shown). Insulin and triglyceride were positively related to the central fat measured by the DXA trunk fat (Table 3, p < 0.05), but not to the waist circumference (Table 2). In the BP model, waist circumference was a significant predictor for both systolic BP and DBP, while DXA-trunk fat was associated with DBP only. Significant interactions between sex and trunk fat, sex and total fat were found in relation to DBP. In boys, DBP was positively related to the trunk fat (p = 0.03); in girls, DBP was positively related to the total fat (p = 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis with insulin, triglyceride, and blood pressure as the dependent variables with waist circumference as the central fat index*

| β | P | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin (log-transformed) | |||

| Intercept | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.45 |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.07 | |

| Sex (boy = 1, girl = 0) | −0.21 | 0.01 | |

| Waist (cm) | 0.01 | 0.19 | |

| Weight (cm) | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| Triglyceride (log-transformed) | |||

| Intercept | −0.96 | 0.47 | 0.13 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.19 | |

| Sex (boy = 1, girl = 0) | 0.03 | 0.52 | |

| Waist (cm) (log-transformed) | 0.06 | 0.80 | |

| Weight (log-transformed) | 0.65 | 0.01 | |

| Height (cm) | −0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | |||

| Intercept | 43.85 | 0.01 | 0.43 |

| Waist (cm) | 0.05 | 0.01 | |

| Height (cm) | 0.22 | 0.01 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure | |||

| Intercept | 27.51 | 0.01 | 0.36 |

| Waist (cm) | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Height (cm) | 0.17 | 0.01 |

The initial model included age, sex, waist, weight, height, and interactions between sex and waist, sex and weight, and sex and height. The independent variable with the largest p value was removed in a stepwise backward elimination procedure until all variables remaining in the model were statistically significant (p < 0.05) or until the central fat index was the next variable to be removed.

Discussion

In this study of prepubertal Chinese children, trunk fat was significantly associated with higher levels of insulin and triglyceride in both boys and girls, and with higher DBP in boys. Trunk fat adjusted for body size (total fat and height), an index of central fat distribution, was a better predictor of metabolic risks in healthy Chinese prepubertal children, compared with waist circumference.

Our results demonstrate a sex difference in body fat distribution in these prepubertal Chinese children, where girls had more trunk fat than boys. In a previous study of Asian children living in New York City, we found that Asian girls had more gynoid fat (the sum of fat in pelvis and legs) than boys using DXA (25). Differences in subject characteristics in these two studies, namely, New York Asians were older, had less fat mass, were of mixed ethnic background (Korean and Chinese), and different dietary habits or physical activity level between the two countries, may have contributed to study differences.

Fat distribution measured by either anthropometry (6–8) or DXA (5) has been reported as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in African-American and white children. In African-American and white children and adolescents 9 to 17 years of age, Daniels et al. (5) reported a strong relationship between android fat distribution and cardiovascular risk factors, including high triglycerides, low HDL-cholesterol, and high systolic BP. To our knowledge, there have been no previous investigations in Chinese prepubertal children on the relationship between body fat distribution (using DXA measurement) and potential cardiovascular risk factors.

It is recognized that the strength of the associations between body composition and metabolic factors seem to be different among race groups. For example, Yanovski et al. (26) reported that both basal and 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test serum insulin levels were significantly correlated with subcutaneous adipose tissue assessed by magnetic resonance imaging in black girls but not in white girls. Several studies in adults have now reported that the relationship between body fat (BMI or percentage body fat) and health risks is different in Asians compared with white populations (27–29). Asian adults tend to have metabolic abnormalities at lower BMI, which may be attributable to greater amounts of visceral adipose tissue (30).

Waist circumference has been identified as a predictor of the insulin resistance syndrome and is recommended to be included in clinical practice as a simple tool to help identify children at risk in studies of black and white children (31,32). However, in Asian children, the association between waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors is less clear. In a study investigating serum lipid profiles in 4-to 16-year-old obese Chinese children, skinfold thickness, and hip and waist circumferences were not found to be related to serum total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and triglyceride (33). In contrast, in a study of 9- to 13-year-old Japanese children, the waist-to-height ratio was reported as the most significant predictor of cardiovascular risk factors, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (34). In agreement with the previous Chinese study (33), waist circumference was not associated with either insulin or triglyceride level, in our pediatric sample. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to report an association between central fat distribution measured by DXA and biomarkers of health risk, namely, higher insulin and triglyceride levels in both prepubertal Chinese boys and girls.

Pietrobelli et al. (35) found significant inverse correlations between HDL and non-adipose components (i.e., adipose tissue-free mass and skeletal muscle mass by magnetic resonance imaging and body cell mass by total body potassium counting) in adults. However, in the current pediatric sample, we did not find a significant association between HDL and any body composition measure (BMI, body weight, or DXA measures of total body fat, trunk fat, total body lean mass, or trunk lean mass).

The observation that DXA-trunk fat, but not waist circumference, is related to certain risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes is an important point of discussion. We acknowledge that the information from our pediatric sample may not be representative of all Chinese children in China. The other limitation is that trunk fat measured by DXA cannot separate abdominal subcutaneous from intra-abdominal fat mass, which may play different independent roles in metabolic parameters.

In summary, central fat distribution measured by DXA is associated with higher insulin, triglyceride, and DBP in this healthy prepubertal sample, while waist circumference is associated with BP only. These findings could suggest that waist circumference and DXA-trunk fat measure different components of body fat, at least in this sample of Chinese prepubertal children. Where the waist circumference measurement is easy to use, it may not be as sensitive in predicting cardiovascular risk factors compared with the DXA measurement of trunk fat, in young and non-overweight subjects. Future studies should include the measurement of visceral fat mass (36) and its sub-depots (omental, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal) to explore the nature of central fat and the mechanisms of the association with metabolic risk.

Acknowledgment

Funded in part by an educational grant to the Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University from Bristol-Myers Squibb Mead Johnson Foundation. We acknowledge Mary Horlick for her contributions in training Xiaojing Zhang in pubertal assessments.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations: SLRHC, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital; JMCH, Jinan Maternity and Childcare Hospital; BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

References

- 1.Contaldo F, Di Biase G, Panico S, Trevisan M, Farinaro E, Mancini M. Body fat distribution and cardiovascular risk in middle-aged people in southern Italy. Atherosclerosis. 1986;61:169–172. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(86)90077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannel WB, Cupples LA, Ramaswami R, Stokes J, 3rd, Kreger BE, Higgins M. Regional obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90265-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams MJ, Hunter GR, Kekes-Szabo T, Snyder S, Treuth MS. Regional fat distribution in women and risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:855–860. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.3.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sardinha LB, Teixeira PJ, Guedes DP, Going SB, Lohman TG. Subcutaneous central fat is associated with cardiovascular risk factors in men independently of total fatness and fitness. Metabolism. 2000;49:1379–1385. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.17716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels SR, Morrison JA, Sprecher DL, Khoury P, Kimball TR. Association of body fat distribution and cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents. Circulation. 1999;99:541–545. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman DS, Serdula MK, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relation of circumferences and skinfold thicknesses to lipid and insulin concentrations in children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:308–317. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1453–1458. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maffeis C, Corciulo N, Livieri C, et al. Waist circumference as a predictor of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in obese girls. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:566–572. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Z, He Q, Fan Z. National epidemiological study on obesity of children aged 0–7 years in China 1996. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1998;78:121–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwata F, Hara M, Okada T, Harada K, Li S. Body fat ratios in urban Chinese children. Pediatr Int. 2003;45:190–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2003.01688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison DB, Paultre F, Goran MI, Poehlman ET, Heymsfield SB. Statistical considerations regarding the use of ratios to adjust data. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:644–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weststrate JA, Deurenberg P, van Tinteren H. Indices of body fat distribution and adiposity in Dutch children from birth to 18 years of age. Int J Obes. 1989;13:465–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan G. Performance of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in evaluating bone, lean body mass and fat in pediatric subjects. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:369–374. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen MD, Kanaley JA, Roust LR, et al. Assessment of body composition with use of dual energy x-ray absorptiometry evaluation and comparison with other methods. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:867–873. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haarbo J, Gotfredsen A, Hassager C, Christiansen C. Validation of body composition by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. Clin Physiol. 1991;11:331–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1991.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison JA, Khoury PR, Chumlea WC, Specker B, Campaigne BN, Guo SS. Body composition measures from underwater weighing and dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in black and white girls: a comparative study. Am J Hum Biol. 1994;6:482–490. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1310060409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Q, Horlick M, Fedun B, et al. Trunk fat and blood pressure in children through puberty. Circulation. 2002;105:1093–1098. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner JM. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1962. Growth at Adolescence. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. Report of the Second Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children—1987. Pediatrics. 1987;79:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazess RB, Barden HS, Bisek JP, Hanson J. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for total-body and regional bone-mineral and soft-tissue composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:1106–1112. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.6.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueroa-Colon R, Mayo MS, Treuth MS, Aldridge RA, Weinsier RL. Reproducibility of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements in prepubertal girls. Obes Res. 1998;6:262–267. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity world-wide:international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAS Institute Inc. SAS User’s Guide: Statistics. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1999. Version 8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Q, Horlick M, Thornton J, et al. Sex and race differences in fat distribution among Asian, African-American, and Caucasian prepubertal children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 87;:2164–2170. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanovski JA, Yanovski SZ, Filmer KM, et al. Differences in body composition of black and white girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996 64;:833–839. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko GTC, Chan JC, Cockram CS, Woo J. Prediction of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia or albuminuria using simple anthropometric indexes in Hong Kong Chinese. Int J Obes. 1999 23;:1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deurenberg-Yap M, Chew SK, Lin FP, van Staveren WA, Deurenberg P. Relationships between indices of obesity and its comorbidities among Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. Int J Obes. 2001 25;:1554–1562. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou B-F. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults: study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002 15;:83–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YW, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Gallagher D. Larger amounts of visceral adipose tissue in Asian Americans. Obes Res. 2001 Sep;:381–387. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janssen GK, Katzmarzyk PT, Srinivasan SR, et al. Combined influence of body mass index and waist circumference on coronary artery disease risk factors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005 115;:1623–1630. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirschler V, Aranda C, Calcagno Mde L, Maccalini G, Jadzinsky M. Can waist circumference identify children with the metabolic syndrome? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:740–744. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S, Liu X, Okada T, Iwata F, Hara M, Harada K. Serum lipid profile in obese children in China. Pediatr Int. 2004;46:425–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2004.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hara M, Saitou E, Iwata F, Okada T, Harada K. Waist-to-height ratio is the best predictor of cardiovascular disease risk factors in Japanese schoolchildren. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2002;9:127–132. doi: 10.5551/jat.9.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pietrobelli A, Lee RC, Capristo E, Deckelbaum RJ, Heymsfield SB. An independent, inverse association of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol concentration with nonadipose body mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:614–620. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leung SS, Chan YL, Lam CW, Peng XH, Woo KS, Metreweli C. Body fatness and serum lipids of 11-year-old Chinese children. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:363–367. doi: 10.1080/08035259850156896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]