Abstract

Upon antigen binding, the BCR transduces a signal culminating in proliferation or in AICD of the B cell. Coreceptor engagement and subsequent modification of the BCR signal pathway are mechanisms that guide the B cell to its appropriate fate. For example, in the absence of coreceptor engagement, anti-sIgM antibodies induce apoptosis in the human Daudi B cell lymphoma cell line. ITIM-bearing B cell coreceptors that potentially may act as negative coreceptors include FcRγIIb, CD22, CD72, and CEACAM1 (CD66a). Although the role of CEACAM1 as an inhibitory coreceptor in T cells has been established, its role in B cells is poorly defined. We show that anti-sIgM antibody and PI3K inhibitor LY294002-induced apoptosis are reduced significantly in CEACAM1 knock-down clones compared with WT Daudi cells and that anti-sIgM treatment induced CEACAM1 tyrosine phosphorylation and association with SHP-1 in WT cells. In contrast, treatment of WT Daudi cells with anti-CD19 antibodies does not induce apoptosis and has reduced tyrosine phosphorylation and SHP-1 recruitment to CEACAM1. Thus, similar to its function in T cells, CEACAM1 may act as an inhibitory B cell coreceptor, most likely through recruitment of SHP-1 and inhibition of a PI3K-promoted activation pathway. Activation of B cells by anti-sIgM or anti-CD19 antibodies also leads to cell aggregation that is promoted by CEACAM1, also in a PI3K-dependent manner.

Keywords: SHP-1, apoptosis, activation-induced cell death, cell aggregation

Introduction

CEACAM1 (CD66a; biliary glycoprotein) is a member of the Ig superfamily and the CEA family of molecules. It is a type I membrane glycoprotein known to mediate homotypic cell adhesion through binding of the most distal IgV-like ectodomain, the N-domain [1]. CEACAM1 is expressed as a number of different splice variants in humans, with one, three, or four extracellular Ig-like domains and a L or S cytoplasmic tail (e.g., CEACAM1-4L is the four domain-long cytoplasmic isoform) [2, 3]. The CEACAM1-L encodes two ITIMs, which when phosphorylated, bind SHP-1, and endows CEACAM1 with inhibitory functions in epithelial cells, T cells, B cells, and NK cells [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. For example, we have shown that during the time course of human T cell activation, CEACAM1 is induced and corresponds with a decrease in IL-2R expression and the response of T cell lines to IL-2 [9]. Furthermore, enforced expression of CEACAM1 in human Jurkat cells leads to inhibition of proliferation and their activation response to IL-2 [9, 11]. Although there are a few publications exploring the function of CEACAM1 in human B cells, its role as a BCR coreceptor is controversial. In one study, a chimeric protein with the extracellular domains of FcRγIIb and the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 gave an inhibitory signal in chicken DT-40 cells [4]. In another study about murine B cells, anti-CEACAM1 antibodies provided an activating signal in the presence of anti-sIgM antibodies [12]. In our study, CEACAM1-positive human B cells isolated from IL-2-stimulated PBMCs underwent cell death when treated with bacteria that bind to CEACAM1 as a cell-surface receptor [10]. Thus, there is a real need to clarify the role of CEACAM1 in B cells.

To study the function of CEACAM1 in human B cells, we chose the Daudi cell line, a germinal center-like Burkitt’s lymphoma B cell line as a model system. These cells mimic normal B cell function in that they undergo AICD in response to anti-sIgM treatment [13, 14]. As these cells constitutively express CEACAM1, we established CEACAM1 knockdown clones (89-9 and 89-15) using lentiviral vectors encoding CEACAM1-specific siRNA. We found that anti-sIgM treatment-induced apoptosis is reduced significantly in CEACAM1 knockdowns compared with WT cells and anti-sIgM-induced CEACAM1 tyrosine phosphorylation and association with SHP-1 in WT cells. In agreement with these results, SHP-1 has been found constitutively associated with the BCR complex and plays an inhibitory role in B cell signaling through ITIM-bearing inhibitory coreceptors [15, 16]. For example, CD22, FcγRII2B1, and CD72 may negatively regulate BCR signaling through recruitment of SHP-1 in human [17, 18] and in murine B cells [19, 20], respectively.

The BCR signal transduction pathway includes a number of key intermediates, several of which are thought to be responsible for AICD. These include ERK1/2, JNK, calcineurin, caspase-9, and PI3K [21]. CEACAM1 has been linked to JNK phosphorylation in murine B cells [12] and to PI3K signaling in human epithelial cells [22] and monocytes [23], and SHP-1 activation has been linked to JNK signaling and apoptosis with BCR stimulation in the murine B lymphoma cell line WEHI-231 [16, 24, 25]. As SHP-1 can regulate PI3K activity by acting directly on the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K [26, 27], a further connection to CEACAM1 is possible. However, we show here that neither the JNK inhibitor SP600125 nor FK506, an inhibitor of calcineurin (upstream of JNK activation), led to an enhancement or protection from AICD in WT or CEACAM1 knockdown Daudi cells. Instead, we found that CEACAM1 promotes BCR-mediated AICD by reducing PI3K signaling. In agreement with this idea, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, which induced apoptosis in WT Daudi cells (high CEACAM1 expression), further enhanced apoptosis in anti-sIgM-treated WT cells. In contrast, CEACAM1 knockdown clones exhibited less anti-sIgM-mediated AICD than WT Daudi cells. Importantly, the CEACAM1 knockdown clones are resistant to LY294002 treatment (compared with WT Daudi cells), suggesting that PI3K signaling is more active in these cells. Taken together, these data support the idea that BCR-mediated AICD operates via the PI3K pathway and that high CEACAM1 expression sensitizes Daudi cells to AICD by reducing PI3K signaling.

In addition to AICD, treatment of B cells with anti-sIgM or anti-CD19 antibodies leads to LFA-1-mediated cell aggregation with a greatly accelerated time course for anti-CD19 antibody treatment [28]. CD19 is a positive signal-transducing component of the complex with an extensive cytoplasmic domain bearing several tyrosines in ITAMs, which can bind Src family kinases, and when phosphorylated, recruits PI3K to the BCR [29, 30]. The production of a complete B cell repertoire, the development of germinal centers in lymph nodes, and the formation of diverse antibody responses depend on CD19 expression [31, 32]. Although a native ligand has not been identified, there is some evidence that the germinal center marker, CD77 (globotriasoyl ceramide), may act as a ligand for CD19 [33]. However, CD19, like BCR itself, may be stimulated with antibodies to produce potent signals. For example, when B cells are stimulated with mAb to CD19, the cells form aggregates in a LFA-1-dependent and independent manner [28, 34]. The B cell aggregates resemble the dense B cell structure of germinal centers in lymph nodes, where B cell–B cell adhesion presumably is required. The connection of this phenomenon to B cell activation and its mechanism is poorly understood. As CEACAM1 mediates homotypic cell adhesion in a variety of cell types through its IgV-like N-terminal domains [35,36,37], it is possible that it also regulates CD19-mediated B cell aggregation. In support of this idea, treatment of murine B cells with anti-CEACAM1 in combination with anti-sIgM antibodies enhanced LFA-1-mediated B cell aggregation [12]. Upon anti-CD19 stimulation of Daudi cells, we found that CEACAM1 colocalized with CD19 and actin at the sites of cell–cell adhesion. Treatment of WT and CEACAM1 knockdown Daudi cells with anti-CD19 antibody demonstrated a dose-response decrease in B cell aggregation, indicating that CEACAM1 promotes cell aggregation. In addition, we found that treatment of Daudi cells with the CD19 antibody leads to an association among CEACAM1, CD19, and PI3K and that the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 reduced B cell aggregation in a dose-dependent manner. As expected, antibodies to LFA-1 or its cognate ligand ICAM1 also inhibited anti-CD19-mediated B cell aggregation. We conclude that CEACAM1 regulates the CD19-mediated activation of LFA-1, which is ultimately responsible for B cell aggregation, and that the effect is mediated by PI3K.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

LY294002 was from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Phalloidin Texas Red conjugate was purchased from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Methyl-β-cyclodextran and cytochalasin B were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). SP600125 and FK506 were from A.G. Scientific (San Diego, CA, USA) and z-LEHD-fmk from BD PharMingen (San Jose, CA, USA).

Cells

Human PBMCs were purified by Ficoll/Hypaque gradient centrifugation, suspended in RPMI with 10% FBS at 106 cells/mL in the presence or absence of human IL-2 (250 U/mL). Naïve, untouched B cells were purified from fresh PBMCs using the auto-MACS with the naïve B Cell Isolation Kit II or positively selected with CD19 beads from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA, USA). The resulting B cells were >95% CD19-positive. The human Daudi Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 from ATCC with 10% FBS (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA), 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium-pyruvate, 1500 mg/L sodium bicarbonate, and antibiotic/antimycotic agent (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). 293T/17 cells were also obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM with 4.5 g/L glucose (Gibco), 10% FBS, and 0.1% sodium-bicarbonate (Gibco). Puromycin (2.5 μg/mL) from Sigma-Aldrich was used for selecting and maintaining the 89pFIV-transduced Daudi clones.

89pFIV viral production

The pFIV system, consisting of the pFIV-H1-puro siRNA cloning vector and pFIV-PACK Lentiviral Vector Packaging Kit, were purchased from System Biosciences (Mountain View, CA, USA). The 89 CEACAM1 siRNA sense sequence (5′ GATGAATGAAGTTACTTAT 3′) was selected from a number of potential sequences provided by the siRNA Target Finder and Design Tool on the Ambion website (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and corresponds to nucleotides 1574–1592 (based on the CEACAM1 sequence National Center for Biotechnology Information gi:68161539) in the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1. The 89pFIV plasmid and the pFIV pack plasmid cocktail were transfected into 293T/17 cells, which then produced the 89pFIV lentivirus. Daudi cells were exposed to the culture media containing the pantropic 89pFIV lentivirus. Cells were cultured with 2.5 μg/mL puromycin for selection of successfully, virally transduced cells. Single cells were FACS-sorted into individual wells of a 96-well plate based on their low-surface CEACAM1 expression detected by surface fluorescent staining with T84.1 antibody. Singly sorted cells grown up in selection media were tested for low CEACAM1 expression and two clones (89-9 and 89-15) used for further studies.

Western blot analysis

Cells were counted, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer. Protein quantitation was conducted using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cell lysates were diluted with loading buffer and run on Nupage gels (Invitrogen) before transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) was used for 1 h of blocking and for 1 h primary and secondary antibody incubations. PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 was used to wash the membrane after each antibody incubation. The Western blot was imaged using the Odyssey infrared imaging system and Odyssey software.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA from the WT Daudi and 89pFIV clones was isolated using the RNeasy Plus Mini and RNeasy MinElute Clean-up kits, according to the supplementary protocol for purification of RNA from animal cells (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Total RNA (25 μg) was denatured and run on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (50% urea) in Tris-boric acid-EDTA buffer. The RNA was transferred to Hybond N+ membrane (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer and fixed to the membrane by UV cross-linking. The membrane was blocked with ULTRAhyb-Oligo buffer (Ambion) and probed with a 32P-labeled probe against the 89 sense sequence (5′ ATAAGTAACTTCATTCATC 3′) diluted in ULTRAhyb-oligo buffer and washed with 6× subacute sclerosing panencephalitis 0.1% SDS. A phosphor-imaging screen was exposed to the membrane for 48 h and then scanned by the Typhoon Imager (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). The 59 nt hairpin 89pFIV plasmid insert was run as a positive control. A 32P-labeled U6 probe (5′ TATGGAACGCTTCTCGAATT 3′) was used as a loading and RNA quality control.

Antibodies

The CEA pan-specific mAb used for IP and Western blot analysis, T84.1, was generated in our lab. 5F4 is a CEACAM1-specific mAb generously provided by Dr. Richard Blumberg (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA). Alexa 488-conjugated antibody for sIgM was from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen). CD19 FITC-conjugated antibody was from Caltag (Burlingame, CA, USA), and that used for treating cells was anti-CD19 from BD PharMingen. F(ab′)2 anti-IgM/G for BCR stimulation was from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA, USA). This is a polyclonal antibody that recognizes surface IgG and IgM. As it is capable of cross-linking sIgM/G and FcRIIb, an inhibitory coreceptor for BCR, it is important that the Fc region is removed before use. The SHP-1 antibody used for IP was from BD PharMingen and for immunoblotting was from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA, USA). 4G10 was from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY, USA). CEACAM1-L cytoplasmic tail-specific rabbit polyclonal antibody, 22-9, has been described previously [9].

Flow cytometry

WT Daudi and 89-9 and 89-15 cells were plated at 0.5 ×105 cells/mL, cultured for 48 h before being counted, and washed, and 1 × 106 were resuspended into 100 μL of a cold solution of primary antibody diluted into PBS with 0.1% human IVIG and 0.5% BSA. Samples are incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Cells are washed with PBS and resuspended in cold PBS for flow cytometric analysis. For 5F4 (anti-CEACAM1 antibody) staining, samples were resuspended into secondary antibody diluted into PBS with 0.1% human IVIG and 0.5% BSA and incubated for 30 min before washing and resuspending in cold PBS for flow analysis.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected using the Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit from BD PharMingen. WT Daudi, 89-9 and 89-15 cells were cultured at 0.5 ×105 cells/mL in 5 mL in T25 flasks for 24 h before treatment with inhibitors. After 90 min of treatment with LY294002 or Z-LEHD-fmk or 30 min with FK506 or SP600215, 10 μg/mL anti-IgM/G was added, and cells were cultured 48 h more. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS before being resuspended in 100 μL Annexin V binding buffer with PI and Annexin V-FITC. Samples were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 min before the addition of Annexin V binding buffer and analyzed by using flow cytometry. Quadrants on the FL1 versus FL2 plot were set according to Annexin V- and PI-alone stained samples.

IP

SHP-1 IP was performed with SHP-1 mAb bound to protein G agarose beads. WT Daudi cells were treated with 20 μg/mL anti-CD19, 40 μg/mL anti-IgM/G, and 100 μM pervanadate for 5 min and washed with cold PBS with 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, 40 pM cypermethrin, and 2 nM calyculin. Cells were lysed in cell lysis/binding buffer including TBS, 1% NP-40, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, 40 pM cypermethrin, 2 nM calyculin, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The samples were microcentrifuged and the supernatant transferred to a chilled tube with 10 μg SHP-1 or isotype control antibody (MOPC21, Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with gentle rocking at 4°C overnight. Prewashed protein G agarose beads were added and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. Samples were washed gently with fresh cell lysis/binding buffer before the beads were resuspended in SDS loading buffer and boiled. Samples were loaded and subjected to the Western blot protocol.

For CEACAM1 IP, WT Daudi cells were treated as above, washed with cold PBS with 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, 40 pM cypermethrin, and 2 nM calyculin, and then lysed in cell lysis/binding buffer. Samples were precleared by incubating with T84.66 (an anti-CEA mAb generated in our lab) bound to POROS epoxide resin (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in cell lysis/binding buffer. Samples were then incubated with T84.1 bound to POROS epoxide resin in cell lysis/binding buffer for 18 h before washing. SDS loading buffer (nonreducing) was added to the beads and incubated at 37°C. The supernatant/immunoprecipitate samples were run according to the Western blot protocol.

Confocal analysis of CEACAM1, CD19, and actin

Daudi cells were plated on fibronectin-coated slides and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min with 0 or 10 μg/mL anti-CD19 FITC-conjugated or 0 or 10 μg/mL anti-CD19 biotin-conjugated antibody. Slides were chilled and stained with T84.1-Alexa 594 conjugate anti-CEACAM1 antibody at 4°C. Cells were then fixed with 0.25% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Tween-20, and stained with phalloidin-Alexa 488. After staining, the samples were washed and mounted in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) before observation and digital photographing with the Zeiss Upright LSM510 2 photon microscope.

Microscopic observation of CD19-induced B cell aggregation and inhibition of aggregation

Daudi cells were plated in culture media and left untreated or treated with 1 μg/mL anti-CD19 or 5 μg/mL anti-CD19 or a combination of 5 μg/mL anti-CD19 with 5 μM methyl-β-cyclodextran, 5 μg/mL or 10 μg/mL cytochalasin B, 5 μM or 20 μM LY294002, or 10 μg/mL blocking antibodies to LFA-1 or ICAM-1. The cells were incubated for 18 h at 37°C before observation and photographing with the Leica DM IL inverted microscope.

Quantitation of B cell aggregation

Daudi cells were dispensed at 2.5 × 105/mL into 24-well plates in triplicate. Cells were incubated with or without 150 μg/mL T84.1 F(ab′)2 for 90, 60, or 30 min prior to treatment with 1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL anti-CD19, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 15 min, 90 min, or 24 h. The samples were stirred over ice with a pipette tip, diluted with stirring, and counted immediately. The size range (7–15 μm) was established by microscopic visualization to make sure that single cells did not contain doublets or aggregates. The average count was calculated for triplicate wells and used to determine the average and se for each treatment.

Statistical analysis

Assay results are expressed as means ± se and unpaired t-tests were used for comparisons. All P values are two-sided. Data were analyzed with SPSS software (Release 10.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism software, Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

CEACAM1 expression in human PBMC and lymph nodes

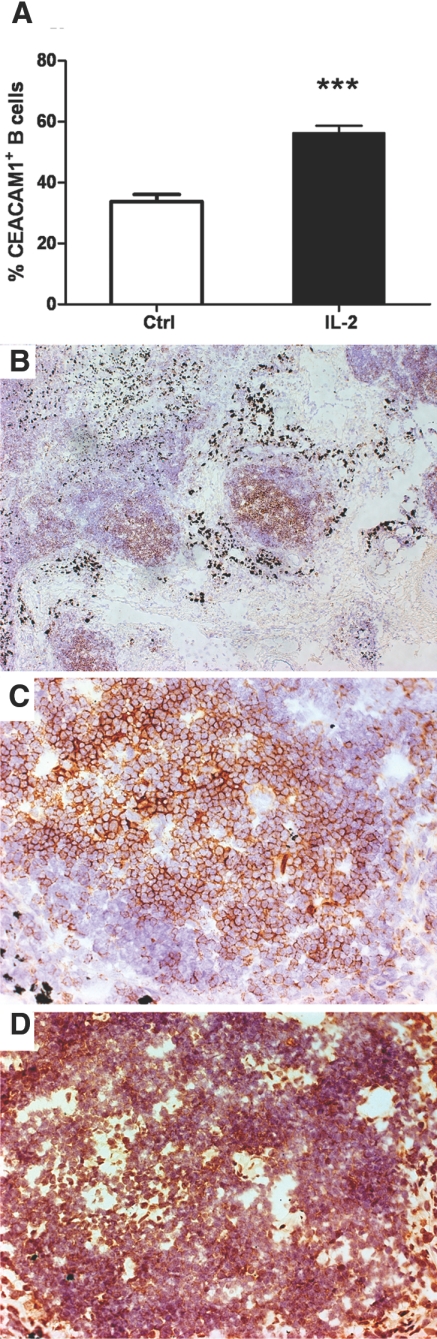

Although CEACAM1 has been reported previously [12] to be expressed on human B cells isolated from PBMCs, we have not been able to reproduce this finding. When B cells were isolated from five independent donors by positive (anti-CD19 beads) or negative isolation protocols, we found no detectable CEACAM1 on these cells using two different anti-CEACAM1 antibodies (5F4, T84.1; data not shown). However, when PBMCs are cultured in the presence or absence of IL-2 for 3 days, the CD19-positive cells express CEACAM1, with highest expression in the IL-2-treated cultures (60%-positive, Fig. 1A). These results confirm our study published previously [10] and suggest that only activated B cells express CEACAM1. However, B cells activated in this manner and purified by “positive” or “negative” isolation methods undergo rapid, spontaneous apoptosis and cannot be studied further.

Figure 1.

Expression of CEACAM1 in IL-2-treated PBMCs and the germinal centers of lymph nodes. (A) PBMCs (1×106 cells/mL) were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-2 (250 U/mL) and the percent CEACAM1+CD19+ cells were analyzed at 3 days [***, P<0.001, in comparison with control (Ctrl)]. (B) Identification of germinal centers in human lymph nodes by anti-CD19 staining (100× original magnification). (C) CD19 staining of a single germinal center (200× original magnification). (D) CEACAM1 staining of a single germinal center (200× original magnification).

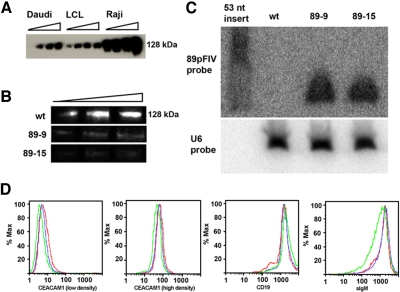

As naïve B cells are CEACAM1-negative, we next examined human lymph nodes for CEACAM1 expression on B cells. Indeed, we found abundant expression of CEACAM1 on B cells in germinal centers (Fig. 1, B–D), in agreement with the strong expression of CEACAM1 on three B cell lines (Daudi, Raji, and a LCL), which originated from germinal centers (Fig. 2A). All three lines expressed CEACAM1 at the cell surface (data not shown), but on close examination, the total levels of CEACAM1 expressed were dependent on cell density (Fig. 2, A and D). As the cells at high density had a high percentage of apoptosis (up to 40% at >106 cells/mL), and we planned to study AICD, all further experiments were performed at a low cell density (<2.5×105 cells/mL), where the percent of Annexin V-positive cells was <10%. We chose the Daudi B cell line for the majority of the AICD experiments, as they are representative of germinal B cells and respond to BCR stimulation by undergoing AICD over a period of 24–48 h [38, 39].

Figure 2.

Characterization of 89-9 and 89-15 CEACAM1 knockdown Daudi clones. (A) Western blot detection of CEACAM1 levels in three human B cell lines grown at different densities (0.25, 0.50, 0.75) and 1.5 × 106 cells/mL. Total protein loaded was 10 μg/lane. (B) Western blot detection of CEACAM1 expression in WT and 89-9 and 89-15 Daudi clones. Total protein loaded was 5, 10, and 15 μg/lane. (C) Northern blot of WT Daudi, 89-9 clone, and 89-15 clone total RNA probed for the 89pFIV sense sequence and U6 RNA. (D) Flow cytometric analysis for surface expression of CEACAM1 (CD66a), sIgM, and CD19 in WT Daudi (red), 89-9 (blue), and 89-15 (green).

Generation of CEACAM1 knockdown clones in Daudi cells

To characterize the effect of BCR stimulation in the presence or absence of CEACAM1, we generated CEACAM1 knockdown clones using lentiviral transduction of Daudi cells with a CEACAM1 siRNA expression plasmid, 89pFIV, followed by FACS selection of low-expression clones. A single siRNA was chosen out of a total of four predicted siRNAs for its ability to knock down CEACAM1 expression in epithelial cells (data not shown). The use of a single siRNA was mandated, as attempts to transfect Daudi cells with this (or other) siRNAs under standard lipofectamine and electroporation conditions failed, and even with a lentiviral plasmid system, no apparent changes in the cell-surface expression of CEACAM1 were observed. After transduction with 89pFIV and selection in puromycin, single cells were sorted by flow cytometry into 96-well plates based on the lowest 3% of CEACAM1 expression. Among the surviving clones, two clones, 89-9 and 89-15, gave a sustained, reduced cell-surface expression level of CEACAM1 compared with WT Daudi cells grown at low or high density (Fig. 2D). In addition, the total CEACAM1 expression level, detected at the mRNA level (data not shown) and by Western blot (Fig. 2B) was reduced dramatically. Characterization of the two clones (89-9 and 89-15) by FACS (Fig. 2D) revealed similar surface levels of sIgM and CD19 compared with WT Daudi cells. CD19 was analyzed, as it is a major marker for B cells and an activating B cell coreceptor. When mRNA levels of CEACAM1 were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR, CEACAM1 mRNA was decreased by five- and tenfold in the 89-9 and 89-15 clones, respectively, compared with WT Daudi cells (data not shown). To demonstrate that the knockdown of CEACAM1 was a result of the expression of the siRNA, Northern blot analysis was performed on both clones (Fig. 2C). The results demonstrate no expression of the CEACAM1 siRNA in WT cells and comparable expression of siRNA in both knockdown clones.

Role of CEACAM1 in AICD

As we hypothesize that CEACAM1 expression has an effect on anti-sIgM-mediated AICD, we first tested this idea on CD19+ CEACAM1+ cells from IL-2-treated PBMCs. As shown in Figure 3A, anti-sIgM treatment has a greater effect on IL-2-treated cells than on untreated controls. Thus, the greater the expression of CEACAM1 on CD19+ cells, the higher the percentage of anti-sIgM-mediated AICD.

Figure 3.

Effect of CEACAM1 expression on anti-sIgM-induced apoptosis. (A) PBMC (1×106 cells/mL) cultured in the presence or absence of IL-2 (250 U/mL) for 3 days were treated with anti-sIgM (10 μg/mL) and the percent CD19+CEACAM1+Annexin V+ (AV+) cells measured over 3 days (**, P<0.01 at Day 3). (B) Treatment of WT Daudi cells, 89-9, and 89-15 (0.5×105 cells/mL) with anti-sIgM (10 μg/mL) resulted in apoptosis, as measured by loss of Annexin V–PI– cells. (Upper panel) No treatment; (lower panel) treatment with anti-sIgM. Stable knockdown of CEACAM1 expression in the 89-9 and 89-15 clones protected from apoptosis after anti-sIgM treatment, as shown by the increase in the percent Annexin V–PI– cells (left to right, WT, 89-9, 89-15). (C) Anti-CEACAM1 antibody treatment suppresses AICD. Daudi cells (0.5×105 cells/mL) were treated with anti-sIgM (0.25 μg/mL) for 24 h in the presence or absence of anti-CEACAM1 antibodies (5 μg/mL), and the percent Annexin V+PI– cells was determined (*, P<0.01, in comparison with isotype control).

Second, to determine the functional significance of CEACAM1 in B cell signaling, the WT Daudi cells and CEACAM1 knockdown clones were subjected to anti-sIgM-mediated AICD. The percent healthy cells (Annexin V–PI–) was reduced from 88% to 18% with 34% single-positive (Annexin V+) and 44% double-positive (Annexin V+PI+) in the WT Daudi cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the 89-9 and 89-15 knockdone clones showed a higher percentage of healthy, nonapoptotic cells than WT Daudi cells treated and analyzed under the same conditions. The 89-15 knockdown clone also consistently showed a higher percentage of the double-negative population than the 89-9 clone, indicating that lower CEACAM1 expression correlates with resistance to AICD. These data also suggest that the greater the CEACAM1 expression, the higher the AICD and are consistent with CEACAM1 acting as a negative B cell coreceptor.

As CEACAM1 is a homotypic cell adhesion molecule, its effect on AICD may be mediated by this activity. Consistent with this idea, Daudi cells exhibit a high degree of spontaneous apoptosis when cultured at high density (>40% at >106 cells/mL; data not shown) and a low degree of spontaneous apoptosis when cultured at low density (<10% at <2.5×105 cells/mL; data not shown). As will be demonstrated later, anti-CEACAM1 antibodies block anti-CD19-induced aggregation, and we reasoned that anti-CEACAM1 antibodies may also block anti-sIgM-mediated AICD. Indeed, that was the case (Fig. 3C), supporting the idea that the cell adhesion activity of CEACAM1 may play a role in its promotion of AICD. (Note: To avoid confusion about the possible agonist or antagonist activities of the anti-CEACAM1 antibodies used in the context of inhibition, we refer to them as “blocking” antibodies.)

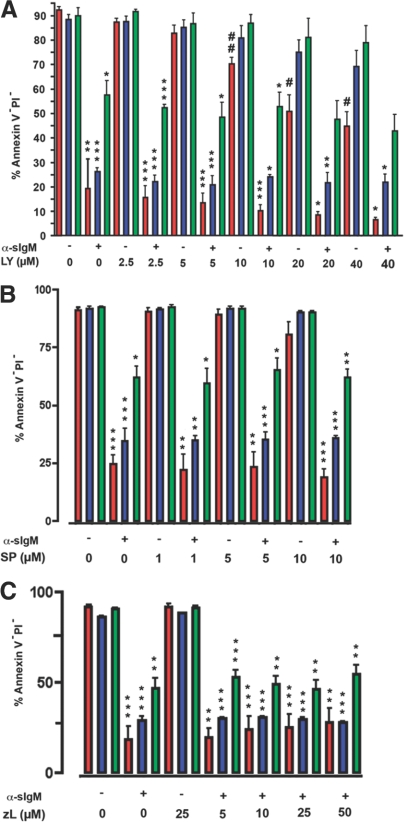

Signaling pathways in AICD

Several downstream signaling pathways were investigated for their role in AICD in CEACAM1-positive Daudi cells. PI3K, an important downstream mediator of BCR signaling, has been linked to anti-sIgM-induced apoptosis in the murine B cell lymphoma cell line ECH408 [21, 40]. Furthermore, PI3K has been implicated in CEACAM1-mediated monocyte apoptosis [23]. To test the role of PI3K in AICD, WT Daudi cells and the knockdown clones were treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 in the presence or absence of anti-sIgM antibody and the apoptosis assay repeated as above. The percent healthy (Annexin V–PI–) WT Daudi cells was reduced from 19% to 7% in a dose-dependent manner upon treatment with LY294002 plus anti-sIgM antibody (Fig. 4A). The WT Daudi cells also exhibited a dose response to LY294002 treatment alone (P<0.001), suggesting that treatment with anti-sIgM antibody or LY294002 affected the same pathway. The apoptotic effect of LY294002 alone on Daudi cells is consistent with other studies [40,41,42]. The CEACAM1 knockdown clones are highly resistant to treatment with LY294002 alone compared with WT Daudi cells, revealing that CEACAM1 can deliver a “death signal” independent of BCR-induced AICD. Indeed, treatment of the CEACAM1 knockdown clones with LY294002 plus anti-sIgM antibody had no additive effect on apoptosis. In the case of the 89-15 clone that expresses the lowest amount of CEACAM1, the highest dose of LY294002 tested (40 μM) reduced the healthy cell population from 90% to 43% compared with 92% to 7% for the WT Daudi cells. Thus, CEACAM1 expression in this B cell line plays a major role in making these cells susceptible to AICD by counteracting antiapoptotic signals from the PI3K pathway. These results are consistent with its putative role as a tumor suppressor, where its absence in cancer cells protects the cells from the induction of apoptosis [43].

Figure 4.

Effect of PI3K, JNK, and caspase-9 inhibitors on anti-sIgM-induced apoptosis on Daudi cells and CEACAM1 knockdown clones. WT (red) and CEACAM1 knockdown clones 89-9 (blue) and 89-15 (green) were treated in triplicate with PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (LY), JNK inhibitor SP600125 (SP), or caspase-9 inhibitor z-LEHD-fmk (zL) and then treated or not with anti-sIgM antibody (α-sIgM) and the percent healthy cells (Annexin V–PI–) recorded. P values were calculated for untreated versus anti-sIgM-treated cells (*, P<0.01: **, P<0.001: ***, P<0.0001) or for untreated versus inhibitor-treated cells (#, P<0.01; ##, P<0.001). Note that with increasing amounts of LY294002 treatment, increased cell death was observed for the WT cells but not for the CEACAM1 knockdown clones. A similar effect was not seen for the JNK or caspase-9 inhibitor.

Although JNK signaling has also been implicated in anti-sIgM antibody AICD, there is some debate as to whether it promotes or reduces apoptosis [21, 25, 44]. As CEACAM1 signaling has been tied to JNK activity in murine B cells [12] and T cells [11], it was important to test the effect of JNK inhibitors on the Daudi cells and the CEACAM1 knockdown clones. To test the role of JNK in AICD of Daudi cells, we used the JNK/stress-activated protein kinase inhibitor SP600125, which has been used to treat murine and human lymphoma cells [45]. Three doses of SP600125 did not protect the WT or knockdown clones from anti-sIgM AICD nor did it promote apoptosis (Fig. 4B). The inhibitor alone caused some cell death at the highest dose (10 μM), yet this dose did not cause an increase in the apoptosis of any of the samples treated with anti-sIgM and SP600125 when compared with those treated with anti-sIgM alone. We conclude that the JNK pathway is not a major effector of BCR AICD in Daudi cells.

In terms of further downstream effectors of apoptosis, caspases may play a role in the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. In this regard, as caspase 9 has been reported to play a role in BCR-mediated apoptosis in tonsillar human B cells and BL60 human Burkitt lymphoma cells [46, 47], we have tested the effect of the specific caspase 9 inhibitor z-LEHD-fmk on WT Daudi cells and the CEACAM1 knockdown clones 89-9 and 89-15. The results indicate that there is no caspase 9 requirement for apoptosis for the WT or CEACAM1 knockdown clone (Fig. 4C). In their work with BL60 cells, Bouchon et al. [47] found that caspase 9 activity is downstream of the mitochondrial pore transition, thus z-LEHD-fmk does not prevent cell death; it just stops part of the downstream apoptotic processes. Our data with Daudi stand in agreement with their results.

Similar to JNK, the activation of ERK1/2 in BCR-mediated apoptosis has been claimed to play a role but remains controversial [48,49,50,51]. For example, calcineurin signaling can lead to JNK, p38, and NFATc2 activation, and these pathways have been described as essential to BCR-mediated apoptosis in several Burkitt lymphoma cell lines [21, 44, 52]. Therefore, we tested the effect of the MEK inhibitor (PD98059) and the calcineurin inhibitor (FK506) in our system; however, neither of these inhibitors tested at three doses had an effect on anti-sIgM AICD (data not shown). Taken together, this series of experiments suggests that the main effector of the pathway is PI3K.

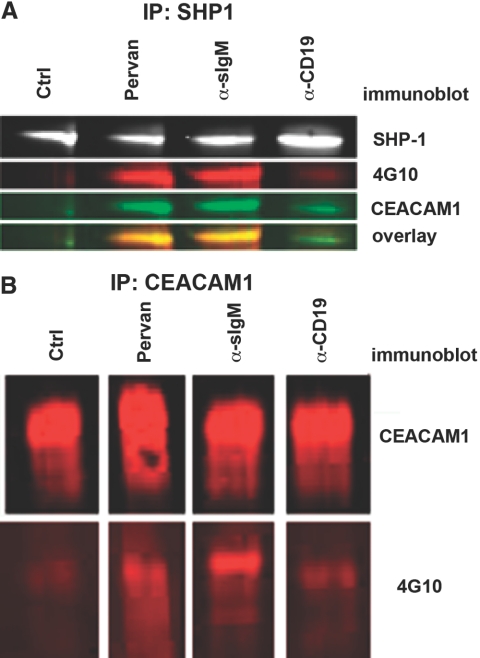

CEACAM1 becomes Tyr-phosphorylated and associates with SHP-1 with anti-sIgM antibody treatment

As the above studies suggest that CEACAM1 can deliver a potent apoptotic signal in the context of BCR, and its absence renders the BCR less susceptible to AICD, it was important to determine if tyrosines in the ITIM are phosphorylated and subsequently recruit SHP-1 upon BCR stimulation. Previously, other ITIM-bearing cell-surface receptors have been identified as inhibitory B cell coreceptors, mediating their effects through SHP-1, one of the major effectors that bind to phosphorylated ITIMs [16, 19, 20, 53]. In support of this, CEACAM1 has been described as an inhibitory molecule in a variety of systems and has been shown to mediate its inhibitory action through the phosphorylation of its ITIM and subsequent recruitment of SHP-1, and mutation of the tyrosines in the ITIMs blocks SHP-1 recruitment [6, 8, 54,55,56]. To test this idea, SHP-1 immunoprecipitates from untreated, pervanadate-treated, anti-IgM-treated, or anti-CD19-treated WT Daudi cell lysates were probed with antibodies to SHP-1, phosphotyrosine, and CEACAM1. Pervanadate, a tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, served as a positive control in that it is expected to promote tyrosine phosphorylation in a nonspecific manner. Anti-CD19 treatment served as a further control, as it acts as a positive coreceptor of B cells and in the case of Daudi cells, does not induce apoptosis. The Western blots shown in Figure 5A demonstrate that roughly equivalent amounts of SHP-1 are present in each of the immunoprecipitates and that it is coassociated with Tyr-phosphorylated CEACAM1 in the pervanadate-treated control cells and in the anti-IgM-treated cells. In contrast, there is only a modest association of CEACAM1 with SHP-1 following CD19 stimulation and none in the untreated cells. When cell lysates are immunoprecipitated with anti-CEACAM1 antibodies and probed with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies, the pervanadate or anti-sIgM-treated cells stain positive, and the untreated cells are negative (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the SHP-1 IP study, only a small amount of CEACAM1 is phosphorylated upon treatment with anti-CD19 antibodies. We conclude that BCR stimulation results in significant phosphorylation of CEACAM1 on its tyrosine ITIMs and recruitment of SHP-1. The recruitment of SHP-1 is expected to dephosphorylate otherwise activating kinases involved in BCR signaling, leading to an overall negative signaling upon activation of BCR only in the presence of CEACAM1. In contrast, activation of CD19 results in minimal phosphorylation of CEACAM1 and minimal recruitment of SHP-1 (Fig. 5B), thus not leading to a net negative signaling pathway. Addition of anti-CEACAM1-blocking antibodies also inhibits phosphorylation of CEACAM1 (data not shown), consistent with their ability to block AICD (Fig. 3C).

Figure 5.

CEACAM1 is tyrosine-phosphorylated and immunopreciptates with SHP-1 with anti-sIgM stimulation. (A) SHP-1 was immunoprecipitated from WT Daudi cells after no treatment control or treatment with anti-IgM/G (40 μg/mL), pervanadate (Pervan; 100 μM), or anti-CD19 (20 μg/mL). Immunoprecipitates are subjected to immunoblotting with SHP-1, 4G10, or 22-9 (polyclonal anti-CEACAM1 intracellular domain) antibodies. (B) CEACAM1 was immunoprecipitated from WT Daudi cells after no treatment or treatment with anti-IgM/G, pervanadate, or anti-CD19 and then subjected to immunoblotting with T84.1 (monoclonal anti-CEACAM1) or 4G10 antibody.

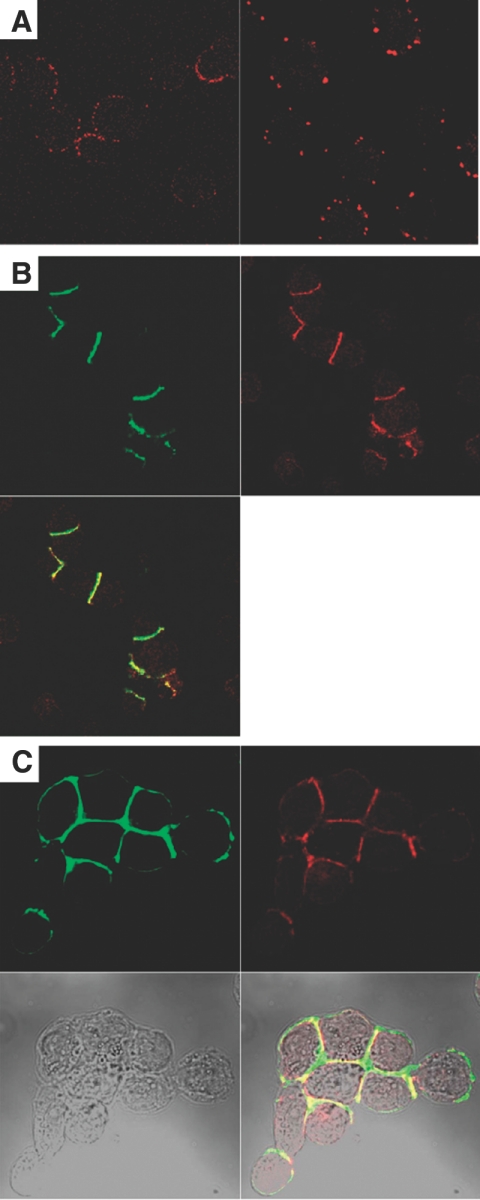

CEACAM1 colocalizes with CD19 and actin at the sites of cell–cell adhesion following anti-CD19 antibody treatment of Daudi cells

During the course of this work, it became clear that stimulation of BCR on Daudi cells with anti-sIgM or anti-CD19 antibodies led to cell aggregation, a phenomenon well-described in the literature. Although the aggregation has been demonstrated to be mediated by LFA-1 and non-LFA-1 mechanisms [28], no role for CEACAM1 has been reported; however, it was also clear that less aggregation occurred in the CEACAM1 knockdown clones. Confocal analysis of CEACAM1 expression on unstimulated Daudi cells reveals evenly distributed, punctuate membrane staining (Fig. 6A), and CD19 appears evenly distributed on the cell membrane (data not shown). After treatment with anti-CD19 antibodies for 30 min, the Daudi cells begin to aggregate, and CD19, CEACAM1, and actin become colocalized at the sites of cell–cell adhesion (Fig. 6, B and C). Although LFA-1 activation is known to be mediated indirectly through the cytoskeleton [57], the direct association of CEACAM1 with the cytoskeleton has also been documented [58] and may suggest that CEACAM1 and LFA-1 contribute to the adhesive contacts.

Figure 6.

CEACAM1 relocates to the sites of cell–cell contact with anti-CD19 stimulation and colocalizes with CD19 and actin. (A) Staining unstimulated Daudi cells with T84.1-Alexa 594-conjugated antibody yielded punctuate yet distributed surface staining (left), which formed larger aggregates when cells were treated with biotinylated T84.1 and Alexa 594 strepavidin (right). (B) Upon anti-CD19 treatment, cells begin to adhere to each other, and CD19 (green) and CEACAM1 (red) staining concentrated at the sites of cell adhesion. (C) Actin (green) also colocalizes with CEACAM1 (red) at the sites of cell–cell adhesion upon anti-CD19 stimulation.

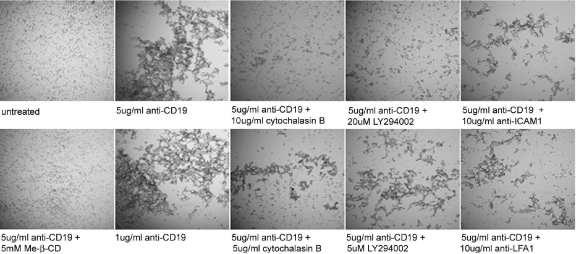

Lipid rafts, actin polymerization, PI3K, LFA-1, and ICAM-1 are required for CD19-mediated B cell aggregation

To better understand the requirements for CD19-mediated B cell aggregation, we tested the effect of chemical inhibitors and blocking antibodies, first in a qualitative microscopic study and then in a quantitative cell-aggregation assay. Anti-CD19 antibody (1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL) induced complete aggregation of the Daudi cells after 18 h of incubation at 37°C (Fig. 7, second from left, upper and lower). Addition of MOPC21, an isotype control for the anti-CD19 antibody, did not induce cell adhesion (data not shown). Pretreatment of the Daudi cells with methyl-β-cyclodextran, a cholesterol-depleting agent that disrupts lipid rafts almost completely, prevented aggregation (Fig. 7, left lower). This result is in agreement with the finding that lipid rafts are necessary for BCR signaling, in which CD19 plays a key role [59]. Given the redistribution of F-actin into the cell–cell contacts following CD19 antibody treatment (Fig. 6C) and the likely need for cytoskeletal stabilization of cell–cell adhesion, we tested the effect of cytochalasin B (5 or 10 μg /mL), an actin polymerization disruptor, on Daudi cell aggregation. Inhibition of aggregation with cytochalasin B treatment exhibits a dose-dependent response (Fig. 7, center panels, upper and lower).

Figure 7.

Lipid rafts, actin polymerization, PI3K, LFA-1, and ICAM-1 are required for CD19-mediated B cell aggregation. Daudi cells were left untreated, treated with anti-CD19 at 1 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL, or treated with 5 μg/mL anti-CD19 concurrently with cholesterol-depleting agent methyl-β-cyclodextran (Me-β-CD), actin-disrupting chemical cytochalasin B, PI3K inhibitor LY294002, or blocking antibody to LFA-1 or ICAM-1. Samples were observed by phase-contrast microscopy after 18 h of incubation at 37°C.

As activated CD19 recruits PI3K into the BCR signaling cascade [30], PI3K is involved in LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated T cell/APC adhesion [60], and PI3K is regulated by CEACAM1 in BCR-mediated AICD, we tested the effect of the PI3K inhbitor LY294002 on CD19-mediated cell aggregation. Indeed, addition of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 inhibited CD19-mediated B cell aggregation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7, second from right, upper and lower).

LFA-1, an integrin comprised of αL- and β2-subunits (CD11a and CD18, respectively), is highly expressed on B cells and when activated, binds ICAM-1 on activated endothelial cells. However, leukocytes, including B cells, also express ICAM-1 on their cell surface, and upon anti-sIgM or anti-CD19 antibody treatment, LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated B cell aggregation is induced [28, 61, 62]. In agreement with these previous studies, we found that LFA-1- and ICAM-1-blocking antibodies effectively inhibited the B cell aggregation induced by anti-CD19 antibody (Fig. 7, right, upper and lower).

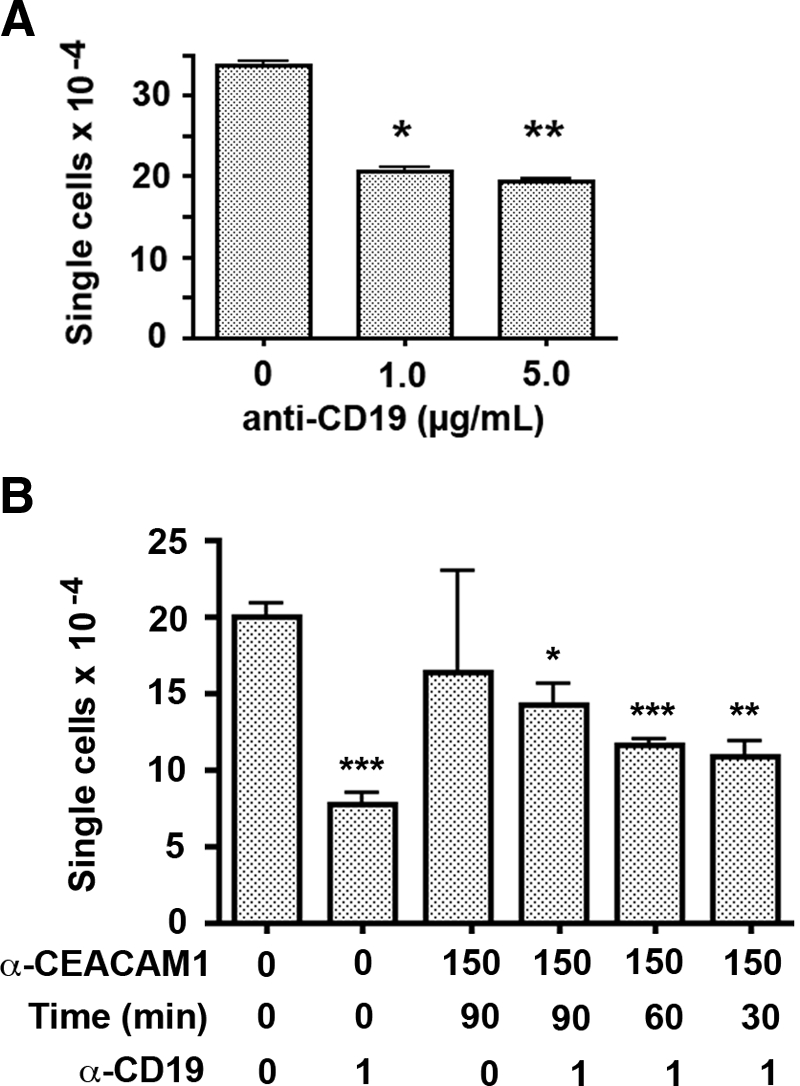

CD19-mediated aggregation of Daudi cells is reduced in CEACAM1 knockdown clones and by anti-CEACAM1 antibody pretreatment

A quantitative assay for B cell aggregation was developed by counting single-cell size particles (7–15 μm) and excluding aggregates in the Coulter counter. As shown in Figure 8A, increasing the dose of anti-CD19 antibody (from 1 to 5 μg/mL) caused lower single-cell counts, indicating increased aggregation, in agreement with the qualitative microscopic observations (Fig. 7). Using this approach to measure remaining single cells, we tested the effect of treatment of Daudi cells with anti-CEACAM1 F(ab′)2 antibody fragments prior to anti-CD19 treatment, and the results were expressed as antibody-treated cell counts divided by the untreated cell counts. As seen in Figure 8B, greater inhibition of aggregation was observed with increased pretreatment time with the anti-CEACAM1 antibody.

Figure 8.

Quantitation of CD19-mediated Daudi cell aggregation. (A) Daudi cell samples were left untreated or treated with anti-CD19 for 15 min, and then single cells were counted in a Coulter counter (particle size, 7–15 μm). With an increasing dose of CD19 antibody, the number of single cells dropped by 43%. P values were calculated versus untreated controls; *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001. (B) WT Daudi cells were preincubated with 150 μg/mL T84.1 F(ab′)2 for 90, 60, or 30 min prior to treatment with anti-CD19 (1 μg/mL) for 90 min. Aggregation was quantitated by counting single cells, and P values were determined by comparison with untreated controls; *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001. Increasing inhibition of cell aggregation was seen with increasing time of anti-CEACAM1 pretreatment.

With CEACAM1 knockdown clones (89-9 and 89-15) expressing 20% and 10%, respectively, of the amount of CEACAM1 mRNA of WT Daudi cells, increased single cells were found after treatment with anti-CD19 antibody, demonstrating that decreased CEACAM1 expression correlates with decreased cell aggregation (Table 1). Taken together, the effect of CEACAM1 F(ab′)2 antibody fragment pretreatment or CEACAM1 knockdown clones on CD19-mediated Daudi cell aggregation indicates that CEACAM1 expression potentiates B cell aggregation.

TABLE 1.

Lower CEACAM1 Expression Results in Less CD-19-Mediated Daudi Cell Aggregationa

WT Daudi and CEACAM1 Knockdown clones 89-9 and 89-15 were cultured in the presence or absence of 1 μg/mL anti-CD19 for 24 h at 37°C and single cells quantitated. Average of triplicate single-cell counts for the anti-CD19-treated simples was divided by the average of triplicate single counts for the untreated samples.

P < 0.01 (comparison of mutants with WT, Student’s t-test).

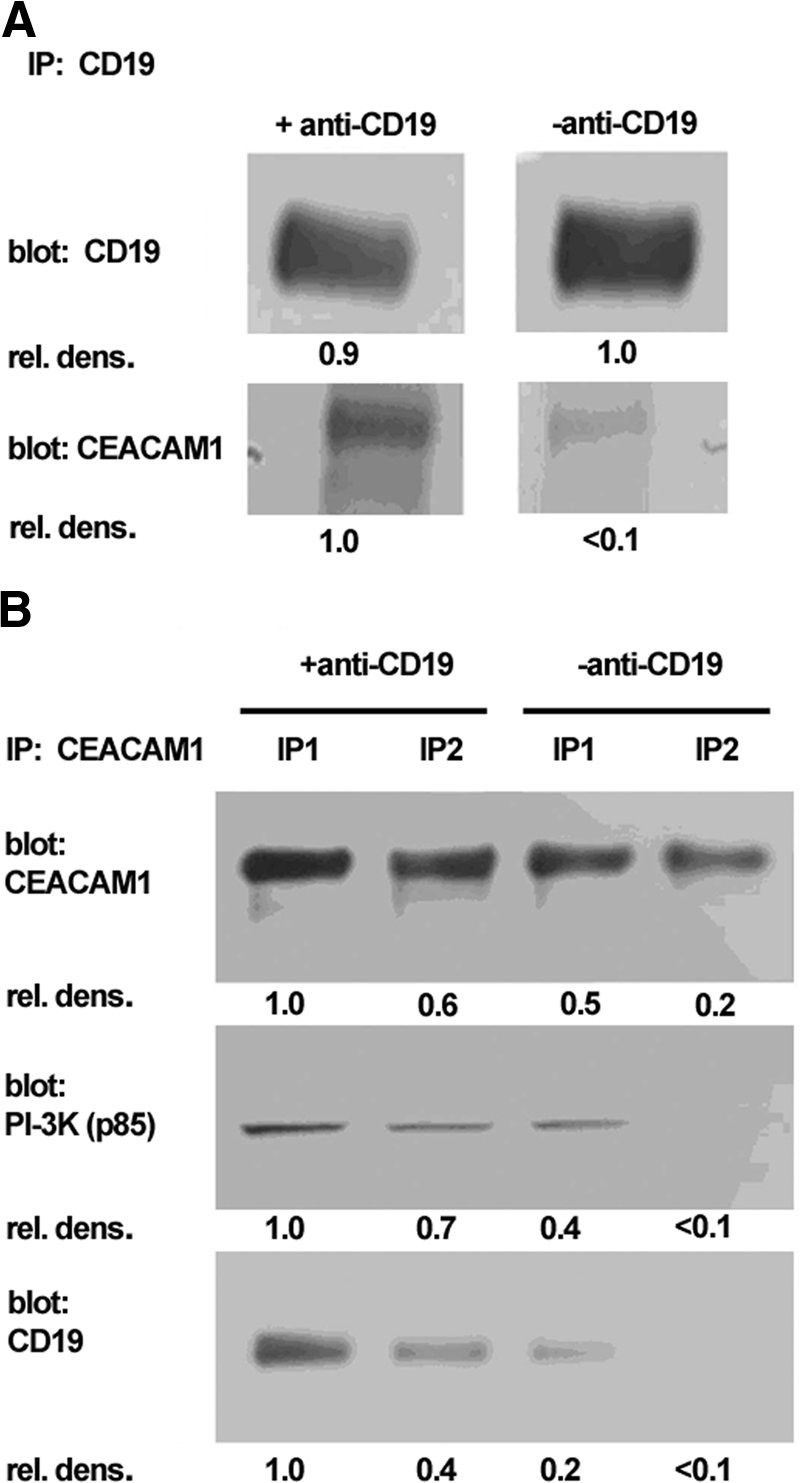

CEACAM1, CD19, and the p85 subunit of PI3K coassociate in Daudi cells after anti-CD19 treatment

As CD19 and CEACAM1 colocalized following CD19 stimulation in Daudi cells (Fig. 6B), and cell aggregation was inhibited by PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (Fig. 7), we performed IP analyses on CD19-stimulated cells using anti-CD19 or anti-CEACAM1 antibodies. As shown in the immunoblot in Figure 9A, anti-CD19 antibody treatment of Daudi cells caused an increased association between CEACAM1 and CD19 in anti-CD19 IPs. The reciprocal IP with anti-CEACAM1 antibodies confirmed the enhanced association of CD19 with CEACAM1 after treatment of Daudi cells with anti-CD19 antibody (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K also coprecipitated with CEACAM1 after treatment of Daudi cells with anti-CD19 antibodies (Fig. 9B). Although it is already known that CD19 recruits and binds PI3K directly upon activation of the BCR, its association with the negative coreceptor CEACAM1 is new, as well as the finding that CEACAM1 is actively involved in the stimulation of B cell aggregation in a PI3K-dependent manner. Stimulation of the BCR with anti-sIgM also leads to B cell aggregation but with slower kinetics than with anti-CD19 stimulation (data not shown), demonstrating that B cell aggregation is a major consequence of BCR stimulation, directly through BCR or indirectly via its coreceptor CD19. However, in the absence of a second signal, BCR stimulation leads to AICD, a fate also involving CEACAM1. Thus, it appears that both events, BCR AICD and B cell aggregation, are linked to the level of PI3K activity, which is in turn controlled by the expression levels of CEACAM1.

Figure 9.

CEACAM1 associates with PI3K and CD19 after stimulation of Daudi cells with anti-CD19 antibody. (A) CD19 was immunoprecipitated from untreated or anti-CD19-treated WT Daudi cells. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to Western blot with anti-CEACAM1 or anti-CD19 antibodies. The CEACAM1 immunoblot indicates increased association of CEACAM1 with CD19 after treatment with anti-CD19 antibody. (B) CEACAM1 was immunoprecipitated from untreated or anti-CD19-treated WT Daudi cells. IP1 is the first immunoprecipitate taken from the beads after 10 min incubation with SDS loading buffer (–DTT) at 37°C. IP2 is the second immunoprecipitate taken from the beads after a further 10-min incubation with SDS loading buffer (+DTT) at 95°C. Immunoblotting for CD19 and the p85 subunit of PI3K indicates enhanced association with CEACAM1 after anti-CD19 stimulation. rel. dens., Relative density.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that CEACAM1 acts as a negative receptor for BCR in the Daudi human B cell lymphoma line. In many respects, this B cell line reflects the default result of BCR-only stimulation, namely AICD. This pathway is critical to the prevention of activation of B cells to self-antigens in the absence of bona fide coactivating signals provided by Th cells. The analysis of this pathway has been an important goal in B cell immunology to provide a rationale for protection against autoimmunity and for the necessary over-riding of this pathway in the establishment of normal immunity. It has long been shown that the ITAM-bearing Igα and Igβ chains of the BCR are responsible for positive signaling, and the ITIM-bearing FcRγIIb receptor is responsible for negative signaling. However, the engagement of FcRγIIb requires the presence of antigen-antibody complexes, which can be shown not to be required for a net negative signaling when BCR alone is stimulated with anti-sIgM antibodies. Thus, there has been an active search for other ITIM-bearing B cell coreceptors, which may be responsible for this negative signaling. The ITIM-bearing receptor CD72 is one such candidate, in that CD72 knockout mice have hyperproliferative responses and a reduction in mature B cells in the circulation [19]. In spite of this evidence, engagement of the CD72 receptor with antibodies or its ligand CD100 results in net activation of B cells [19], making it difficult to reconcile its role as a solely inhibitory coreceptor for B cells. Furthermore, ERK and JNK downstream kinases have been implicated in CD72 signaling, leading to a confusing picture of its ability to transmit negative signals upon BCR stimulation. Thus, other ITIM-bearing receptors, such as CEACAM1, are reasonable candidates to test. Although CD22 contains an ITIM [63], CD22-deficient mice have impaired B cell responses, suggesting a positive role in B cell activation [64].

CEACAM1 is a natural choice as a negative BCR coreceptor based on its proven inhibitory activities in T cells. In the mouse, transfer of naïve T cells, which do not express CEACAM1 to Rag-deficient animals, results in IBD, and T cells transfected with CEACAM1 protect against IBD [6]. The IBD study demonstrated that only the ITIM-bearing isoform of CEACAM1 was able to protect and that mutation of the ITIM tyrosine residues abrogated its inhibitory activity. In other studies in murine and human T cells, it has been shown that engagement of CEACAM1 with cross-linking antibodies or the TCR itself results in phosphorylation of CEACAM1 on its ITIMs and subsequent recruitment of SHP-1 [9, 11]. There have been a few publications suggesting an inhibitory function of CEACAM1 in B lymphocytes: one in which the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 has been shown to substitute for the cytoplasmic domain of FcRγIIb in the chicken B cell line DT-40 [4] and another in which PBMCs were stimulated with IL-2 (or not) for 2–3 days, and the CD19/CEACAM1 double-positive B cells were shown to undergo cell death when treated with Escherichia coli or Neisseria gonorrhea bacteria that use CEACAM1 as a receptor [10]. In apparent contradictory results, murine B cells treated with anti-CEACAM1 antibodies underwent proliferation and clonal expansion, and proliferation was enhanced by the addition of IL-4, anti-sIgM, or both [12]. Although the latter study conflicts with our findings, it is possible that the use of anti-CEACAM1 antibodies may result in agonistic or antagonistic effects or that murine B cells respond differently than human B cells. In addition, murine B cells express a significant amount of the CEACAM1-S [12], which does not contain an ITIM, and this isoform may transmit positive signals in these cells. Importantly, only the CEACAM1-L cytoplasmic domain (ITIM-bearing) isoform is expressed in human lymphocytes, and the short cytoplasmic domain isoform is not expressed by peripheral human B cells [23] or in our study, by Daudi cells.

To probe CEACAM1-mediated signaling in the Daudi cell line, we took advantage of the siRNA strategy for down-regulating the expression levels of CEACAM1. However, the Daudi cell line was resistant to conventional transfection with siRNA oligos, and we had to resort to transduction with a lentiviral vector bearing the siRNA expression plasmid followed by single cell sorting of low CEACAM1-expressing cells to develop clones. Although we were surprised that this approach was necessary, it is important to note that the low CEACAM1-expressing cells were true knockdowns, in that they continued to express the siRNA. We selected two clones for our study based on their differential expression of CEACAM1, one at ∼20% (89-9) and the other at ∼10% (89-15) the mRNA level of the parental cell line. Importantly, our studies do not include a lentivirus control, as virus integration is random in the genome, and the potential complication of insertional mutagenesis is therefore also random [65]. As our clones were obtained by FACS sorting for a range of CEACAM1 expression, we argue that siRNA expression and not random insertional mutagenesis is responsible for their reduced expression of CEACAM1.

In agreement with the prediction that CEACAM1 acts as an inhibitory coreceptor for BCR stimulation, parental cells underwent almost complete AICD after treatment with anti-sIgM antibodies, and the two knockdown clones were differentially resistant in accordance to the degree of CEACAM1 expression. Although the parental cell line was sensitive to PI3K inhibition, the knockdown cells were resistant, implicating PI3K as an immediate downstream mediator of BCR AICD and suggesting that the presence of CEACAM1 prevents PI3K activation. The logical mediator of this effect is the recruitment of SHP-1, which has been shown in other systems to prevent PI3K activation [26]. In agreement with this idea, CEACAM1 was phosphorylated on its ITIM and recruited SHP-1 after BCR stimulation.

The inhibition studies show that ERK1/2, JNK, calcineurin, and caspase 9 activities are not involved in the CEACAM1 promotion of cell death, as none of these inhibitors altered the apoptosis levels of the CEACAM1 knockdown clones differently from the parental Daudi cells. Thus, CEACAM1 modulates BCR signaling differently than CD72 and is perhaps a better candidate for the negative coreceptor function based on the fact that it is active in the absence of any ligand, as CD72 transmits a positive signal in the presence of its ligand [19]. Notably, CEACAM1 is a homotypic cell adhesion molecule and should be capable of transmitting outside-in signals whenever B cells encounter each other (or other CEACAM1-positive cells). Therefore, we are left with PI3K inhibition as the major clue to the downstream effect of CEACAM1 on BCR stimulation. We hypothesize that the phosphorylation of PI3K and its downstream targets are inhibited by the recruitment of SHP-1 to the nascent BCR signal transduction complex by CEACAM1. Thus, in the presence of CEACAM1, tyrosine phosphorylation spreading to “life” signaling molecules does not occur as a result of the presence of SHP-1. This scenario is in contrast with the usurping of phosphorylation of the insulin receptor in CEACAM1 expressing hepatocytes, where CEACAM1, rather than other downstream effectors of the insulin receptor, is phosphorylated [66]. Thus, CEACAM1 can limit phosphorylation of downstream targets by ay least two distinct mechanisms.

Our studies suggest that BCR-mediated AICD acts directly through the PI3K pathway and that expression of CEACAM1 sensitizes these cells to the PI3K pathway by reducing phosphorylation of the p85 subunit. In the reduced presence of CEACAM1, the PI3K pathway is more active and the cells less sensitive to BCR-mediated AICD. Thus, it may be more accurate to state that CEACAM1 acts as a “negative regulator of PI3K” in the context of BCR signaling.

A recent publication presents an opposite story in monocytes. When monocytes were treated with anti-CEACAM1 antibody or with purified soluble CEACAM1, which binds to cell surface-bound CEACAM1, thus acting as a potential ligand, human monocytes were protected from spontaneous apoptosis, and addition of LY294002 abrogated the CEACAM1-mediated protection [23]. Although both sets of results certainly suggest cross-talk exists between the PI3K pathway and CEACAM1, they apparently lead to opposite results. In support of our results, it is known that SHP-1 can dephosphorylate the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K and that this decreases PI3K activity [27], and decreased PI3K activity is associated with BCR-mediated apoptosis [21, 40]. Taken together, these data are consistent with how CEACAM1 promotes apoptosis with anti-sIgM stimulation of B cells. However, the SHP-1 association with CEACAM1 does not explain how LY294002 can prevent monocyte cell death in the presence of CEACAM1. A possible explanation may lie in that CEACAM1 may exist as cis- or trans-dimers on the cell surface [67] and that their different conformational states may dictate the outcome of signaling on stimulation with antibodies or soluble ligand. Alternatively, the recruitment of inactive SHP-1 by CEACAM1 has been reported in neutrophils [68], thus offering the possibility that SHP-1 is sequestered from inhibition of a negative rather than a positive signaling pathway.

Physiologically, the site where B cell–B cell aggregation is most obvious is in the germinal centers of the lymph node. Studies with CD19 knockout mice indicate that CD19 is a requirement for germinal center formation [69, 70]. CD77 (globotriasoyl ceramide), a germinal center marker, is the only suggested ligand for CD19 [70]. The human B cell lymphoma line Daudi expresses CD19 and CD77 and is representative of the germinal center phenotype [70]. In cell culture, activation of CD19 with anti-CD19 antibodies leads to rapid aggregation of Daudi cells. Thus, it is possible that activation of CD19 by CD77 or surrogate ligands such as anti-CD19 antibodies represents a relevant pathway to germinal center formation. As CD19 is also a positive coreceptor for B cell activation, the two processes may be connected at a single point, namely, CD19. In this study, we show that CD19-mediated Daudi cell aggregation is inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or antibodies to CEACAM1. As PI3K is known to associate with CD19, taken together, these studies indicate that there is a signal pathway connecting BCR to CD19-associated PI3K, which is in turn regulated by CEACAM1. The role of CEACAM1 in regulating this pathway is revealed in CEACAM1 knockdown clones that exhibit less AICD and less cell aggregation.

In the absence of direct stimulation of CD19, Daudi cell aggregation still occurs via BCR stimulation but at a slower rate. Thus, BCR stimulation in germinal centers may lead to B cell aggregation via indirect or direct stimulation of CD19, and as CD19 plays a critical role in BCR signaling, B cell aggregation must also be a natural consequence of B cell activation. At this point, one can ask two questions: Why do B cells aggregate in the first place? And why regulate the process with another adhesion molecule such as CEACAM1 when the actual cell adhesion occurs through LFA-1 and ICAM1? The B cell aggregates seen in germinal centers were originally thought to be a consequence of rapidly dividing B cells that merely stayed in place after cell division. However, these cells must stay in place to undergo additional processes such as somatic hypermutation and antigen selection, after which, they are free to leave the lymph node. Thus, a controlled aggregation process may be a necessary step in their development in the lymph node. The presence of the homotypic cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1 may regulate the process positively at the early stages when few aggregates are formed and increasingly regulate the process negatively as the aggregates become larger. This idea is supported by the inhibitory activity of anti-CEACAM1 antibodies. Thus, in the presence of few CEACAM1 adhesive interactions (low state of aggregation or no pretreatment with anti-CEACAM1 antibody), CD19-mediated aggregation is uninhibited, and in the presence of multiple CEACAM1-adhesive interactions (high state of aggregation or pretreatment with anti-CEACAM1 antibodies), aggregation is inhibited (or even terminated). Thus, CEACAM1 regulates the aggregation process in a positive and negative manner depending on the degree of aggregation. This idea is supported by the studies on the CEACAM1 knockdown clones, which reveal that CEACAM1 regulates Daudi cell aggregation positively.

The fact that CEACAM1 regulates BCR AICD and B cell aggregation and that both processes converge on PI3K is interesting. PI3K activation has been shown to be required for cell fate [40] and cell adhesion [71] decisions. These decisions must take into account surrounding cells. In the case of B cells that encounter antigen in the absence of a “second signal,” namely BCR stimulation only, AICD is the likely outcome. This signal may be delivered in the context of the inhibitory coreceptor CEACAM1, which has recruited SHP-1 to the BCR complex, and prevents PI3K activation. Once the cells receive a single signal aggregate, they will be sequestered from sources of second signals and become even more likely to undergo cell-cycle arrest or even apoptosis. They will have low levels of activated PI3K. On the other hand, cells that divide productively after receiving the BCR signal and second signal will activate PI3K and resist cell death, but they will still aggregate. The aggregation would be self-limiting in the presence of the cell adhesion molecule CEACAM1, which would increasingly counteract PI3K activation, otherwise promoting cell division. In this way, CEACAM1 could act as cell–cell sensor, inhibiting PI3K in the case of BCR-stimulated AICD but promoting cell–cell adhesion in the early stages of productive or nonproductive B cell activation. However, as larger and larger aggregates form, signaling through CEACAM1 would increase, ultimately leading to inhibition of even productive B cell activation. This balancing act requires a direct measurement of the size of the germinal center, reigning it in before it grows out of control. This task is best assigned to a cell–cell adhesion molecule that depends on cell density for activation of a negative signaling pathway. CEACAM1 is suited ideally for this task, in that it has been assigned positive and negative roles previously in cell growth and adhesion [72]. The outcome of the balancing act depends on cell context, which in this case, is degree of cell aggregation.

In conclusion, our data reveal the role of CEACAM1 as a negative coreceptor for the BCR, associating with SHP-1 through a phosphorylated, active ITIM and promoting AICD upon anti-sIgM stimulation. In addition, CEACAM1 regulates B cell aggregation, an important step in the formation of germinal centers in lymph nodes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA84202.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AICD=activation-induced cell death, ATCC=American Type Culture Collection, CEACAM1=carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1, FL1=fluorescence 1, IBD=inflammatory bowel disease, IP=immunoprecipitation, IVIG=i.v. Ig, L=long, LCL=lymphoblastoid cell line, NP-40=Nonidet P-40, PI=propidium iodide, S=short, SHP-1=Src homology phosphatase 1, sIgM=surface IgM, siRNA=small interfering RNA, WT=wild-type, z-LEHD-fmk=benzyloxycarbonyl-Leu-Glu-His-Asp-fluoromethylketone

References

- Beauchemin N, Draber P, Dveksler G, Gold P, Gray-Owen S, Grunert F, Hammarstrom S, Holmes K V, Karlsson A, Kuroki M, Lin S H, Lucka L, Najjar S M, Neumaier M, Obrink B, Shively J E, Skubitz K M, Stanners C P, Thomas P, Thompson J A, Virji M, von Kleist S, Wagener C, Watt S, Zimmermann W. Redefined nomenclature for members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:243–249. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett T R, Drake L, Pickle W., II Human biliary glycoprotein gene: characterization of a family of novel alternatively spliced RNAs and their expressed proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1273–1282. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett T, Zimmermann W. Workshop report: proposed nomenclature for the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) gene family. Tumour Biol. 1990;11:59–63. doi: 10.1159/000217643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Zimmermann W, Parker J, Chen I, Maeda A, Bolland S. Biliary glycoprotein (BGPa, CD66a, CEACAM1) mediates inhibitory signals. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray-Owen S D, Blumberg R S. CEACAM1: contact-dependent control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:433–446. doi: 10.1038/nri1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaishi T, Pao L, Lin S H, Iijima H, Kaser A, Qiao S W, Chen Z, Glickman J, Najjar S M, Nakajima A, Neel B G, Blumberg R S. SHP1 phosphatase-dependent T cell inhibition by CEACAM1 adhesion molecule isoforms. Immunity. 2006;25:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markel G, Lieberman N, Katz G, Arnon T I, Lotem M, Drize O, Blumberg R S, Bar-Haim E, Mader R, Eisenbach L, Mandelboim O. CD66a interactions between human melanoma and NK cells: a novel class I MHC-independent inhibitory mechanism of cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2002;168:2803–2810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin N, Kunath T, Roitaille J, Chow B, Turbide C, Daniels E, Veillette A. Association of biliary glycoprotein with protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in malignant colon epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:783–790. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C J, Shively J E. The cell-cell adhesion molecule carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1 inhibits IL-2 production and proliferation in human T cells by association with Src homology protein-1 and down-regulates IL-2 receptor. J Immunol. 2004;172:3544–3552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelic M, Kim Y J, Bolland S, Chen I, Shively J, Chen T. Neisseria gonorrhoeae kills carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1 (CD66a)-expressing human B cells and inhibits antibody production. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4171–4179. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.4171-4179.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Iijima H, Nagaishi T, Nakajima A, Russell S, Raychowdhury R, Morales V, Rudd C E, Utku N, Blumberg R S. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1 isoforms alternatively inhibit and costimulate human T cell function. J Immunol. 2004;172:3535–3543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius G, Severinson E, Beauchemin N, Obrink B, Singer B B. CEACAM1 is a potent regulator of B cell receptor complex-induced activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:126–134. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racila E, Hsueh R, Marches R, Tucker T F, Krammer P H, Scheuermann R H, Uhr J W. Tumor dormancy and cell signaling: anti-μ-induced apoptosis in human B-lymphoma cells is not caused by an APO-1-APO-1 ligand interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2165–2168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marches R, Racila E, Tucker T F, Picker L, Mongini P, Hsueh R, Vitetta E S, Scheuermann R H, Uhr J W. Tumor dormancy and cell signaling–III: role of hypercrosslinking of IgM and CD40 on the induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in B lymphoma cells. Ther Immunol. 1995;2:125–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pani G, Kozlowski M, Cambier J C, Mills G B, Siminovitch K A. Identification of the tyrosine phosphatase PTP1C as a B cell antigen receptor-associated protein involved in the regulation of B cell signaling. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2077–2084. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi T, Wienands J, Wakabayashi C, Yakura H, Reth M, Tsubata T. SHP-1 requires inhibitory co-receptors to down-modulate B cell antigen receptor-mediated phosphorylation of cellular substrates. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26648–26655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100997200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm S, Gerlach J, Brossmer R, Danzer C P, Nitschke L. The ligand-binding domain of CD22 is needed for inhibition of the B cell receptor signal, as demonstrated by a novel human CD22-specific inhibitor compound. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1207–1213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosio D, Hippen K L, Minskoff S A, Mellman I, Pani G, Siminovitch K A, Cambier J C. Recruitment and activation of PTP1C in negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling by Fc γ RIIB1. Science. 1995;268:293–297. doi: 10.1126/science.7716523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D H, Tung J W, Tarner I H, Snow A L, Yukinari T, Ngernmaneepothong R, Martinez O M, Parnes J R. CD72 down-modulates BCR-induced signal transduction and diminishes survival in primary mature B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;176:5321–5328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi T, Flaswinkel H, Yakura H, Reth M, Tsubata T. The B cell surface protein CD72 recruits the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 upon tyrosine phosphorylation. J Immunol. 1998;160:4662–4665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeva J, Pelkonen J. Mechanisms of B cell receptor induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2004;9:525–531. doi: 10.1023/B:APPT.0000038032.22343.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth J W, Telio D, Liao E H, McCaw S E, Matsuo T, Grinstein S, Gray-Owen S D. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule-mediated internalization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14037–14045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Chow E M, Wong H, Gu J, Mandelboim O, Gray-Owen S D, Ostrowski M A. CEACAM1 (CD66a) promotes human monocyte survival via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- and AKT-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39179–39193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Tagawa Y, Mitomo K, Arimura Y, Hatano N, Katagiri T, Ogimoto M, Yakura H. Src homology region 2 (SH2) domain-containing phosphatase-1 dephosphorylates B cell linker protein/SH2 domain leukocyte protein of 65 kDa and selectively regulates c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation in B cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:1344–1351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Tagawa Y, Mitomo K, Watanabe N, Katagiri T, Ogimoto M, Yakura H. Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 positively regulates B cell receptor-induced apoptosis by modulating association of B cell linker protein with Nck and activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. J Immunol. 2002;169:778–786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas B, Lu Y, Watt S, Kumar R, Zhang J, Siminovitch K A, Mills G B. SHP-1 regulates Lck-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase phosphorylation and activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27583–27589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas B D, Lu Y, Mao M, Zhang J, LaPushin R, Siminovitch K, Mills G B. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p85 relieves its inhibitory activity on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27455–27461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S H, Rigley K P, Callard R E. Activation of human B cells through the CD19 surface antigen results in homotypic adhesion by LFA-1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunology. 1991;73:293–297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M, Poe J C, Hasegawa M, Tedder T F. CD19 regulates intrinsic B lymphocyte signal transduction and activation through a novel mechanism of processive amplification. Immunol Res. 2000;22:281–298. doi: 10.1385/IR:22:2-3:281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M R, Ingham R J, McLeod S J, Christian S L, Scheid M P, Duronio V, Santos L, Matsuuchi L. Targets of B-cell antigen receptor signaling: the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase-3 signaling pathway and the Rap1 GTPase. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:47–68. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R H, Wang Y, Brooks S. Role of CD19 signal transduction in B cell biology. Immunol Res. 2002;26:45–54. doi: 10.1385/IR:26:1-3:045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Steeber D A, Jansen P J, Tedder T F. CD19 expression levels regulate B lymphocyte development: human CD19 restores normal function in mice lacking endogenous CD19. J Immunol. 1997;158:4662–4669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney M D, Lingwood C A. CD19 has a potential CD77 (globotriaosyl ceramide)-binding site with sequence similarity to verotoxin B-subunits: implications of molecular mimicry for B cell adhesion and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 1994;180:191–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kansas G S, Tedder T F. Transmembrane signals generated through MHC class II, CD19, CD20, CD39, and CD40 antigens induce LFA-1-dependent and independent adhesion in human B cells through a tyrosine kinase-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 1991;147:4094–4102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M, Fuks A, Stanners C P. Biliary glycoprotein, a member of the immunoglobulin supergene family, functions in vitro as a Ca2(+)-dependent intercellular adhesion molecule. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:527–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa S, Kuroki M, Matsuoka Y, Kosaki G, Nakazato H. Homotypic and heterotypic Ca(++)-independent cell adhesion activities of biliary glycoprotein, a member of carcinoembryonic antigen family, expressed on CHO cell surface. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:881–887. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90828-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira A M, Fawcett J, Simmons D L, Watt S M. The N-domain of the biliary glycoprotein (BGP) adhesion molecule mediates homotypic binding: domain interactions and epitope analysis of BGPc. Blood. 1994;84:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein J S, Lin C K, Wang C L, Nguyen T T, Kalunta C I, Park E, Chen F S, Lad P M. Anti-IgM-mediated regulation of c-myc and its possible relationship to apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18875–18884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marches R, Hsueh R, Uhr J W. Cancer dormancy and cell signaling: induction of p21(waf1) initiated by membrane IgM engagement increases survival of B lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8711–8715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey G B, Scott D W. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in anti-IgM- and anti-IgD-induced apoptosis in B cell lymphomas. J Immunol. 2001;166:1618–1626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmore L, Radda G K, Knox K A. Wortmannin-mediated inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity triggers apoptosis in normal and neoplastic B lymphocytes which are in cell cycle. Int Immunol. 1996;8:585–594. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curnock A P, Knox K A. LY294002-mediated inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity triggers growth inhibition and apoptosis in CD40-triggered Ramos-Burkitt lymphoma B cells. Cell Immunol. 1998;187:77–87. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittka S, Gunther J, Ebisch C, Erbersdobler A, Neumaier M. The human tumor suppressor CEACAM1 modulates apoptosis and is implicated in early colorectal tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:9306–9313. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves J D, Draves K E, Craxton A, Saklatvala J, Krebs E G, Clark E A. Involvement of stress-activated protein kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in mIgM-induced apoptosis of human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13814–13818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururajan M, Chui R, Karuppannan A K, Ke J, Jennings C D, Bondada S. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is required for survival and proliferation of B-lymphoma cells. Blood. 2005;106:1382–1391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berard M, Mondiere P, Casamayor-Palleja M, Hennino A, Bella C, Defrance T. Mitochondria connects the antigen receptor to effector caspases during B cell receptor-induced apoptosis in normal human B cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:4655–4662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchon A, Krammer P H, Walczak H. Critical role for mitochondria in B cell receptor-mediated apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:69–77. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<69::AID-IMMU69>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koncz G, Bodor C, Kovesdi D, Gati R, Sarmay G. BCR mediated signal transduction in immature and mature B cells. Immunol Lett. 2002;82:41–49. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauld S B, Blair D, Moss C A, Reid S D, Harnett M M. Differential roles for extracellularly regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase in B cell antigen receptor-induced apoptosis and CD40-mediated rescue of WEHI-231 immature B cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3855–3864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J R, Koretzky G A. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-2, but not c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, activation correlates with surface IgM-mediated apoptosis in the WEHI 231 B cell line. J Immunol. 1998;161:1637–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J D, Dave S H, Chou C H, Mamchak A A, DeFranco A L. Inhibition of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway blocks a subset of B cell responses to antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:3855–3864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo E, Harashima A, Takabatake T, Takahashi H, Matsuo Y, Yoshino T, Orita K, Akagi T. NF-ATc2 induces apoptosis in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells through signaling via the B cell antigen receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1–11. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke L, Carsetti R, Ocker B, Kohler G, Lamers M C. CD22 is a negative regulator of B-cell receptor signaling. Curr Biol. 1997;7:133–143. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Izzi L, Grondin P, Houde C, Kunath T, Veillette A, Beauchemin N. The carboxyl-terminal region of biliary glycoprotein controls its tyrosine phosphorylation and association with protein-tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:335–344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzi L, Turbide C, Houde C, Kunath T, Beauchemin N. cis-Determinants in the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM1 responsible for its tumor inhibitory function. Oncogene. 1999;18:5563–5572. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Zimmermann W, Parker J, Chen I, Maeda A, Bolland S. Biliary glycoprotein (BGPa, CD66a, CEACAM1) mediates inhibitory signals. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lub M, van Kooyk Y, van Vliet S J, Figdor C G. Dual role of the actin cytoskeleton in regulating cell adhesion mediated by the integrin lymphocyte function-associated molecule-1. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:341–351. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann D, Chen C J, Kaplan B, Shively J E. Carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 directly associates with cytoskeleton proteins actin and tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47421–47433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubata T, Wienands J. B cell signaling. Introduction. Int Rev Immunol. 2001;20:675–678. doi: 10.3109/08830180109045584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K L, Daniels M A, Felthauser A, Kao C, Jameson S C, Shimizu Y. Cutting edge: LFA-1 integrin-dependent T cell adhesion is regulated by both Ag specificity and sensitivity. J Immunol. 2004;173:2222–2226. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius G, Tamosiunas V, Severinson E. Assessment of the role of leucocyte function-associated antigen-1 in homotypic adhesion of activated B lymphocytes. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:642–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang L H, Rock K L. Stimulation of B lymphocytes through surface Ig receptors induces LFA-1 and ICAM-1-dependent adhesion. J Immunol. 1991;146:3273–3279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]