Abstract

Kutznerides are actinomycete-derived antifungal nonribosomal hexadepsipeptides which are assembled from five unsual nonproteinogenic amino acids and one hydroxy acid. Conserved in all structurally characterized kutznerides is a dichlorinated tricyclic hexahydropyrroloindole postulated to be derived from 6,7-dichlorotryptophan. In this communication, we identify KtzQ and KtzR as tandem acting FADH2-dependent halogenases that work sequentially on free l-tryptophan to generate 6,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan. Kinetic characterization of these two enzymes has shown that KtzQ (along with the flavin reductase KtzS) acts first to chlorinate at the 7-position of l-tryptophan. KtzR, with a ~120 fold preference for 7-chloro-l-tryptophan over l-tryptophan, then installs the second chlorine at the 6-position of 7-chloro-l-tryptophan to generate 6,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan. These findings provide further insights into the enzymatic logic of carbon-chloride bond formation during the biosynthesis of halogenated secondary metabolites.

Kutznerides are antifungal nonribosomal hexadepsipeptides produced by the soil actinomycete Kutzneria sp. 744.1 The macrolactone scaffold is assembled from six unusual building blocks. The lactone oxygen is derived from t-butylglycolate while the five amino acid monomers are all nonproteinogenic. In some kutznerides, e.g. kutzneride 2 (1) (Figure 1), there are two chlorinated residues, a tricyclic dihalogenated (2S,3aR,8aS)-6,7-dichloro-3a-hydroxy-hexahydropyrrolo[2,3-b]indole-2-carboxylic acid (diClPIC) and a γ-chloro-piperazate. In addition, we previously suggested that the unusual 2-(1-methylcyclopropyl)-d-glycine (MecPG) residue might arise by cryptic chlorination of an isoleucyl side chain, setting up subsequent closure to the β,γ-cyclopropane.2,3 With the expectation that several halogenation events are operative in kutneride biosynthesis, the cognizant gene cluster in kutzneria was identified by degenerate primer-based PCR amplication through the use of FADH2-dependent and nonheme FeII-dependent halogenase probes.2 Bioinformatic analysis indicated a putative flavin reductase KtzS, two flavin-dependent halogenases KtzQ and KtzR and one mononuclear iron halogenase KtzD, the first example of both flavin and iron halogenase genes encoded together within the same gene cluster.

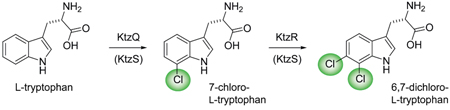

Figure 1.

(A) Kutzneride 2, 1. (B) Formation of 6,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan (6,7-diCl-l-trp) during kutzneride biosynthesis.

In parallel studies,4 we have observed that the nonheme iron halogenase KtzD chlorinates isoleucine bound in thioester linkage to carrier protein KtzC, thus suggesting that KtzQ and KtzR could be responsible for the halogenation in the diClPIC and/or γ-chloro-piperazic acid residues. Comparison to other known flavin halogenases revealed KtzQ shares 60% identity with ThaL, a tryptophan 6-halogenase from Steptomyces albogriseolus,5 whereas KtzR shares 54% identity with PyrH, a tryptophan 5-halogenase from Streptomyces rugosporus,6 suggesting KtzQ and KtzR halogenate tryptophan prior to pyrroloindole formation. In this study, we validate that purified KtzQ and KtzR are tandem acting halogenases that catalyze the regiospecific dichlorination of L-tryptophan to produce 6,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan.

To evaluate the role of the two putative O2- and FADH2- dependent 50 kDa halogenases, the ktzQ and ktzR genes were amplified from genomic DNA isolated from Kutzneria sp. 744 and subcloned for translation as N-terminally His6-tagged enzymes. Soluble protein (1.8 mg/L culture) was obtained for the KtzQ construct when heterologously expressed in and purified from E.coli BL21 (DE3), whereas heterologous expression in Pseudeomonas putida KT2440 was required to provide the KtzR construct in soluble form (1.1 mg/L culture). Both proteins were obtained in over 90% purity after Ni-NTA affinity and gel exclusion chromatographies (Figure S1). The purified enzymes did not contain any cofactor with absorbance in the visible range of the spectrum. To provide the the FADH2 anticipated as substrate for the two halogenases, KtzS was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3), purified as the C-His6-tagged construct, and shown to be an NADH-utilizing FAD reductase. The previously characterized E. coli NAD(P)H dependent flavin reductase SsuE was also prepared.7 Assays for halogenation were conducted in the presence of soluble chloride ions with FAD, NADH and excess KtzS or SsuE to generate the diffusible FADH2 required for halogenase catalysis.

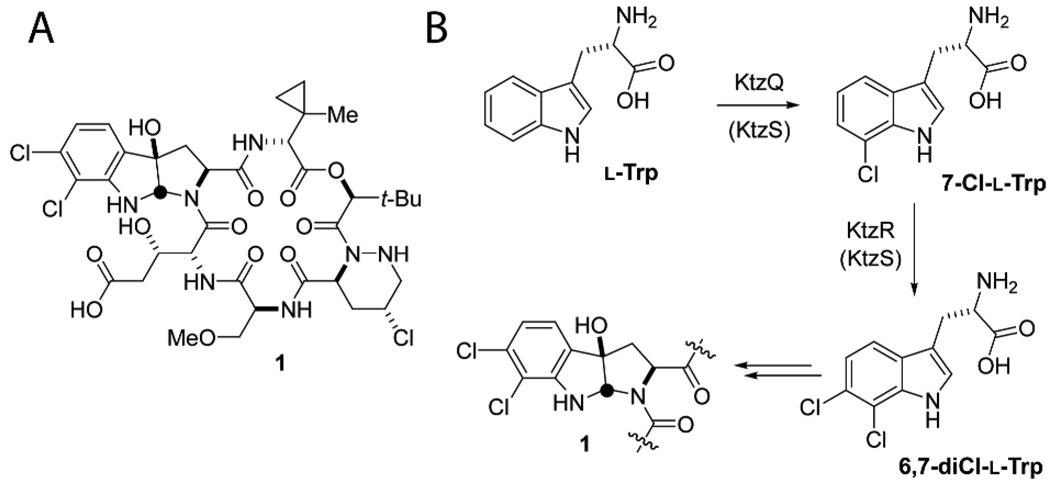

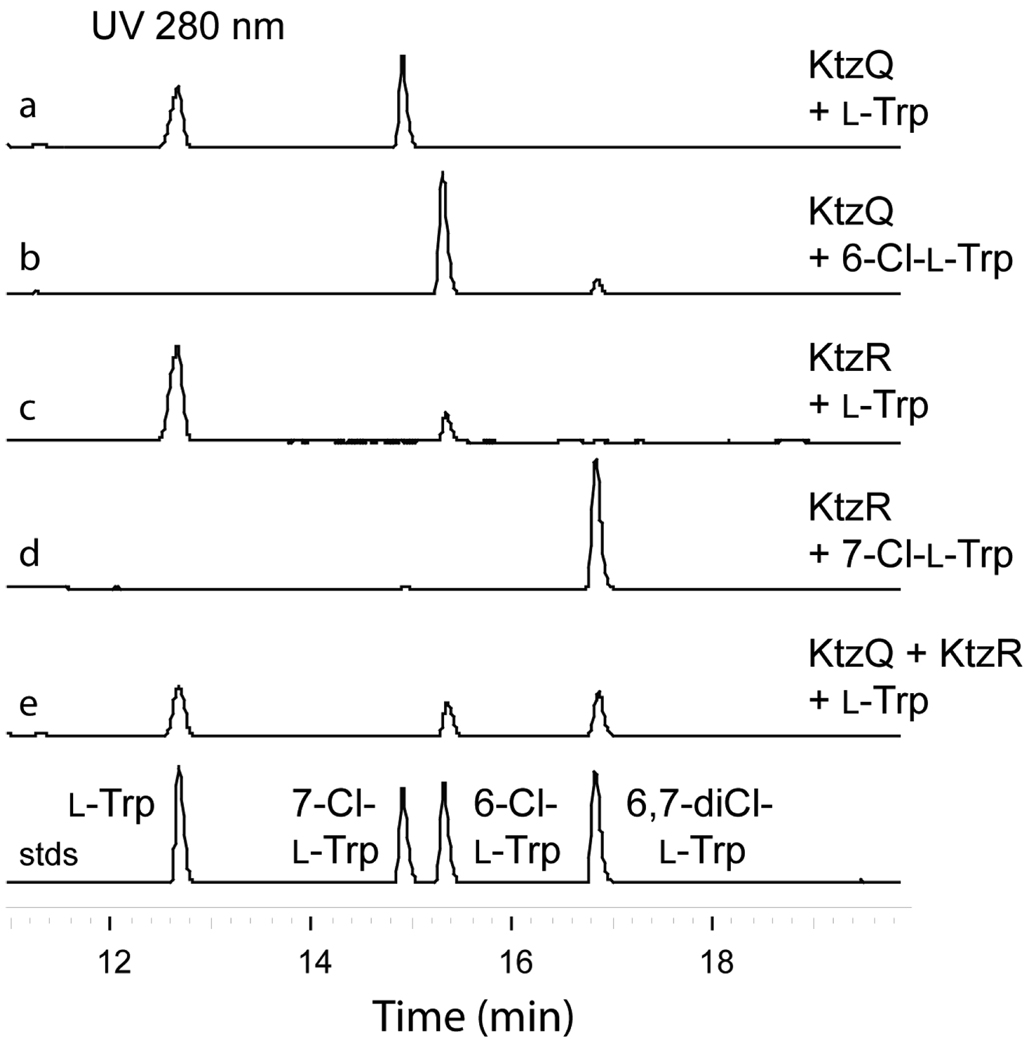

KtzQ showed no activity for chlorination of piperazic acid or γ,δ-dehydropiperazic acid but was active when incubated with l-Trp (Figure 2a) and yielded a product that comigrated with authentic 7-chloro-l-tryptophan (7-Cl-l-Trp) by HPLC analysis. Mass analysis of the reaction product by ESI gave a pair of [M - H]− ions at m/z = 237.0 and 239.0 in a ~3:1 ratio, consistent with a mono-chlorinated Trp compound (Figure S2). Comparison of the 1H-NMR data of the product and authentic 7-Cl-l-Trp further confirmed the site of chlorination at position 7 of the indole ring (Figure S3). When authentic 6-chloro-l-tryptophan (6-Cl-l-Trp) was tested as substrate for KtzQ, a new peak appeared that coeluted with a chemically synthesized standard of 6,7-dichloro-l-tryptophan (6,7-diCl-l-Trp) (Figure 2b). ESI-MS analysis afforded three [M - H]− ions at m/z = 270.9, 272.9, and 274.9 in a ~10:6:1 ratio, consistent with a di-chlorinated Trp compound (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of the KtzQ and KtzR catalyzed halogenations. (a) KtzQ incubated with l-Trp (b) KtzQ incubated with 6-Cl-l-Trp (c) KtzR incubated with l-Trp (d) KtzR incubated with 7-Cl- l-Trp (e) KtzQ and KtzR incubated with l-Trp

To gain further insight into the substrate specificity of KtzQ, kinetic studies were undertaken with l-Trp and 6-Cl-l-Trp. At pH 7.0 under the coupled enzyme assay conditions (KtzS and KtzQ) the kcat for l-Trp to 7-Cl-l-Trp is 0.19 min−1 while for 6-Cl-l-Trp to 6,7-diCl-Trp the kcat is 0.07 min−1. The Km for both Trp and 6-Cl-Trp as substrates is ≤2 µM, at the sensitivity limit of the assay. From these results we conclude KtzQ is a regiospecific tryptophan-7-halogenase which has a preference for halogenation at the 7 position of unmodified l-Trp but will also take the 6-chloro-substrate.

KtzR in turn also chlorinated l-Trp and the halogenated product comigrated with authentic 6-Cl-l-Trp (Figure 2c). The identity of the monochlorinated reaction product was further confirmed by ESI-MS, yielding a pair of [M - H]− ions at m/z = 237.0 and 239.0 in a ~3:1 ratio (Figure S5). When presented with 7-Cl-l-Trp as a halogenation substrate, KtzR was again a regioselective 6-chlorination catalyst, yielding 6,7-diCl-l-Trp as product (Figure 2d). The product identity was also confirmed by ESI-MS ([M - H]− m/z = 270.9, 272.9, and 274.9) (figure S6). Comparison of 1H-NMR data of the product and authentic 6,7-diCl-l-Trp confirmed the site of chlorination at position 6 of the indole ring (Figure S7). Remarkably, the catalytic efficiency for halogenation of position 6 of 7-Cl-l-Trp was better than for l-Trp itself. The kcat ratio for 7-Cl-l-Trp/l-Trp as substrate (1.4 min−1/0.08 min−1) favors 7-Cl-l-Trp by ~18 fold, and the Km value for 7-Cl-l-Trp at 114 µM is ~7 fold lower than for l-Trp at 808 µM, thus the presence of a chloride at the 7-position of the indole ring results in a ~120-fold increase in KtzR efficiency relative to umodified l-Trp. KtzR, like KtzQ, was not active for introduction of chloride to piperazic acid or γ,δ-dehydropiperazic acid.

Tandem incubations of l-Trp with KtzQ and KtzR along with the flavin reductase KtzS or SsuE and NADH and FAD yielded the 6,7-diCl-l-Trp product (Figure 2e). From these results and the individual enzyme kinetics, we conclude that the tandemly organized ktzQ and ktzR genes encode two FADH2-dependent halogenases that work sequentially on free l-Trp in the order of KtzQ followed by KtzR to form 6,7-diCl-l-Trp (Figure 1B). It is then likely that 6,7-diCl-l-Trp is the monomer incorporated into the growing kutzneride assembly line by the KtzH adenylation domain. The final conversion to the diClPIC moiety in mature kutzneride is postulated to be achieved by epoxidation of the indole 2,3-double bond by the hemeprotein KtzM with intramolecular capture of the epoxide by the amide nitrogen.2

KtzQ is a regiospecific tryptophan-7-halogenase analogous to the enzymes RebH8 and PrnA9 that act in the first steps of rebeccamycin and pyrrolnitrin biosynthesis, respectively. The regioselectivity for introduction of chlorine at the 6-position of the indole ring of l-Trp and 7-Cl-l-Trp renders KtzR a homolog of ThaL6 in the thienodolin pathway. ThaL has a turnover of 2.8 min−1 while the Trp-7-halogenases PrnA and RebH perform at 0.1 to 1.4 chlorinations per minute; these values are within range of those measured for KtzQ and KtzR. The kcat values may be faster in vivo if enzyme complexes exist to channel the FADH2 and resultant FAD(C4a)-OOH towards productive chlorination (via generation of HOCl, which is proposed to affect N-chlorination of an active-site lysine side chain to form lysine chloramine as the proximal halogenating species)9c vs competing autoxidation to FAD.

Whereas KtzQ is analogous to all of the previously characterized tryptophan halogenases in its prefence for unmodified l-Trp, KtzR is novel in that it has a ~120 fold prefence for 7-Cl-l-Trp over l-Trp. The substrate binding site in KtzQ is well conserved with PrnA, RebH, ThaL and PyrH and all of the amino acids responsible for binding tryptophan are present. In contrast, two aromatic residues which stack against the indole ring of tryptophan in the PrnA and RebH structures, H101 and W455 in PrnA and H109 and W466 in RebH, are replaced with glutamine and leucine residues respectively in KtzR (Table S1). Structural analysis is warranted to determine if and then how these changes in the active site residues allow KtzR to differentiate 7-Cl-l-Trp from l-Trp.

In summary, our initial characterization of the three enzymes KtzQRS make it likely that the regioselective double halogenation in kutzneride biosynthesis occurs on free l-Trp by sequential action of the KtzQR pair. Kinetic characterization shows KtzQ acts first to chlorinate at the 7-position of l-Trp and then KtzR installs the second chlorine at the 6-position of 7-Cl-l-Trp to generate 6,7-diCl-l-Trp. Thus, while KtzD, Q, and R are now characterized halogenases, the chlorination of the piperazate moiety has not yet been accounted for and may require further genomic analysis of the Kutzneria producer.

Supplementary Material

Figures S1–S7, Table S1, detailed experimental procedures and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgement

We thank Prof. Robert S. Phillips for providing the authentic 7-chloro-l-Tryptophan used in these studies. We also thank Elizabeth S. Sattely for technical assistance and careful proofreading of the manuscript. This work was supported by an NIH grant to C.T.W (GM20011) and by an NIH NRSA fellowship to J.R.H (F32 GM083464).

References

- 1.(a) Broberg A, Menkis A, Vasiliauskas R. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:97–102. doi: 10.1021/np050378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pohanka A, Menkis A, Levenfors J, Broberg A. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:1776–1781. doi: 10.1021/np0604331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujimori DG, Hrvatin S, Neumann CS, Strieker M, Marahiel MA, Walsh CT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:16498–16503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708242104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann CS, Fujimori DG, Walsh CT. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann CS, Walsh CT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:XXX–XXX. doi: 10.1021/ja8064667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seibold C, Schnerr H, Rumpf J, Kunzendorf A, Hatscher C, Wage T, Ernyei AJ, Dong C, Naismith JH, van Pee HK. Biocatalysis and Biotransformations. 2006;24:401–408. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zehner S, Bister B, Sussmuth RR, Mendez C, Salas JA, van Pee K-H. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Eichhorn E, van der Ploeg JR, Leisinger T. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26639–26646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dorrestein PC, Yeh E, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:13843–13848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506964102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Hohaus K, Altmann A, Burd W, Fischer I, Hammer PE, Hill DS, Ligon J, van Pee K-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1997;109:2102–2104. [Google Scholar]; (b) Keller S, Wage T, Hohaus K, Holzer M, Eichhorn E, van Pee K-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2300–2302. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000703)39:13<2300::aid-anie2300>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dong C, Flecks S, Unversucht S, Haupt C, van Pee K-H, Naismith JH. Science. 2005;309:2216–2219. doi: 10.1126/science.1116510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Yeh E, Garneau S, Walsh CT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:3960–3965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500755102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yeh E, Cole LJ, Barr EW, Bollinger JM, Jr, Ballou DP, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7904–7912. doi: 10.1021/bi060607d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yeh E, Blasiak LC, Koglin A, Drennan CL, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1284–1292. doi: 10.1021/bi0621213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1–S7, Table S1, detailed experimental procedures and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.