Abstract

Vertebrate jaw muscle anatomy is conspicuously diverse but developmental processes that generate such variation remain relatively obscure. To identify mechanisms that produce species-specific jaw muscle pattern we conducted transplant experiments using Japanese quail and White Pekin duck, which exhibit considerably different jaw morphologies in association with their particular modes of feeding. Previous work indicates that cranial muscle formation requires interactions with adjacent skeletal and muscular connective tissues, which arise from neural crest mesenchyme. We transplanted neural crest mesenchyme from quail to duck embryos, to test if quail donor-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues could confer species-specific identity to duck host jaw muscles. Our results show that duck host jaw muscles acquire quail-like shape and attachment sites due to the presence of quail donor neural crest-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues. Further, we find that these species-specific transformations are preceded by spatiotemporal changes in expression of genes within skeletal and muscular connective tissues including Sox9, Runx2, Scx, and Tcf4, but not by alterations to histogenic or molecular programs underlying muscle differentiation or specification. Thus, neural crest mesenchyme plays an essential role in generating species-specific jaw muscle pattern and in promoting structural and functional integration of the musculoskeletal system during evolution.

Keywords: Cranial neural crest, jaw muscles, musculoskeletal connective tissues, tendons, Tcf4, Scx, quail-duck chimeras, evolutionary developmental biology

Introduction

The jaw complex has been elemental to the evolutionary success of vertebrates. Composed primarily of skeletal and muscular tissues, the jaws have enabled a multitude of taxa to occupy almost every ecological niche. While much attention has been paid to the anatomical diversification of jaw bones and cartilages, few studies have identified developmental mechanisms that provide species- specific pattern to the closely associated musculature. Because the muscles that attach to the upper and lower portions of the jaw skeleton are integral for respiration and feeding, they have undergone dramatic evolutionary change in conjunction with the adaptive radiations of vertebrates (Bemis and Northcutt, 1991; Bowman, 1961; Cabuy et al., 1999; Edgeworth, 1935; Gosline, 1986; Haas, 2001; Holliday and Witmer, 2007; Smith, 1993; Tomo et al., 2007; Turnbull, 1970; Wood, 1965). For example, in groups such as pufferfish (Friel and Wainwright, 1997) and parrots (Toki*ta, 2004; Zusi, 1993), the number and organization of jaw muscles have been extremely modified, reflecting a high degree of plasticity in the developmental programs of the first (i.e., mandibular) arch (Schneider, 2005; Smith and Schneider, 1998). Moreover, the direct relationship between muscle architecture and feeding mechanics indicates that the ability to modify the jaw complex rapidly is critical for a species to accommodate new ecological conditions (Bellwood and Choat, 1990; Friel and Wainwright, 1999; Herrel et al., 2005; Reduker, 1983; Satoh, 1997; Schaefer and Lauder, 1986; Schneider, 2007; Turingan, 1994; van der Meij and Bout, 2004). Thus, understanding developmental mechanisms that facilitate musculoskeletal connectivity is a central question in the evolutionary biology of vertebrates.

Broad aspects of jaw muscle development have been investigated using a variety of organisms (Ericsson and Olsson, 2004; Gasser, 1967; Hanken et al., 1997; McCleam and Noden, 1988; Rayne and Crawford, 1971; Schilling and Kimmel, 1997; Smith, 1994; Tokita, 2004; Ziermann and Olsson, 2007), mainly in relation to the identification of genes expressed during jaw myogenesis (Bhattacherjee et al., 2007; Bothe and Dietrich, 2006; Dastjerdi et al., 2007; Hacker and Guthrie, 1998; Hatta et al., 1990; Lu et al., 1998; Noden and Francis-West, 2006; Noden et al., 1999; Sauka-Spengler et al., 2002; von Scheven et al., 2006b); genetic specification of the jaw muscle lineage (Dong et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2004; Knight et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2002; Nathan et al., 2008; Shih et al., 2007; Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006; von Scheven et al., 2006a) and tissue interactions that mediate the migration, differentiation, and patterning of myogenic mesenchyme (Borue and Noden, 2004; Ericsson et al., 2004; Grenier et al., 2009; Hall, 1950; Kelly et al., 2004; Noden, 1983b; Noden, 1986; Noden, 1988; Noden and Trainor, 2005; Olsson et al., 2001; Rinon et al., 2007; Rodriguez-Guzman et al., 2007; Schilling et al., 1996; Trainor and Krumlauf, 2000; Trainor et al., 2002; Tzahor et al., 2003). Yet proximate factors that underlie the evolution of jaw muscles remain poorly understood.

Developmentally, jaw muscles are derived from cephalic paraxial mesoderm, which flanks the neural tube (Couly et al., 1992; Evans and Noden, 2006; Noden, 1983b; Wachtler and Jacob, 1986). In contrast, the jaw skeleton forms from cranial neural crest mesenchyme, which arises along the dorsal margins of the neural folds (Jheon and Schneider, 2009; Le Liévre, 1978; Noden, 1978). In addition to bone and cartilage, cranial neural crest mesenchyme gives rise to muscle connective tissues including ligaments, tendons, fascia, and epi- and endomysia (Noden, 1983a). A range of approaches including mutant screens in zebrafish (Schilling et al., 1996), extirpations in amphibians (Ericsson et al., 2004; Olsson et al., 2001), analyses of quail-chick chimeras (Noden, 1983b; Noden, 1986), and gene mis-expression experiments in chick (Grammatopoulos et al., 2000) and Xenopus (Pasqualetti et al., 2000), have revealed that cranial neural crest mesenchyme is important for muscle differentiation and morphology (Francis-West et al., 2003; Köntges and Lumsden, 1996; Noden and Francis-West, 2006; Noden and Schneider, 2006; Noden and Trainor, 2005; Schnorrer and Dickson, 2004). Based on such data, and the fact that musculoskeletal elements of the jaw complex have so intimately co-evolved, we hypothesized that neural crest mesenchyme is also the source of species-specific muscle pattern.

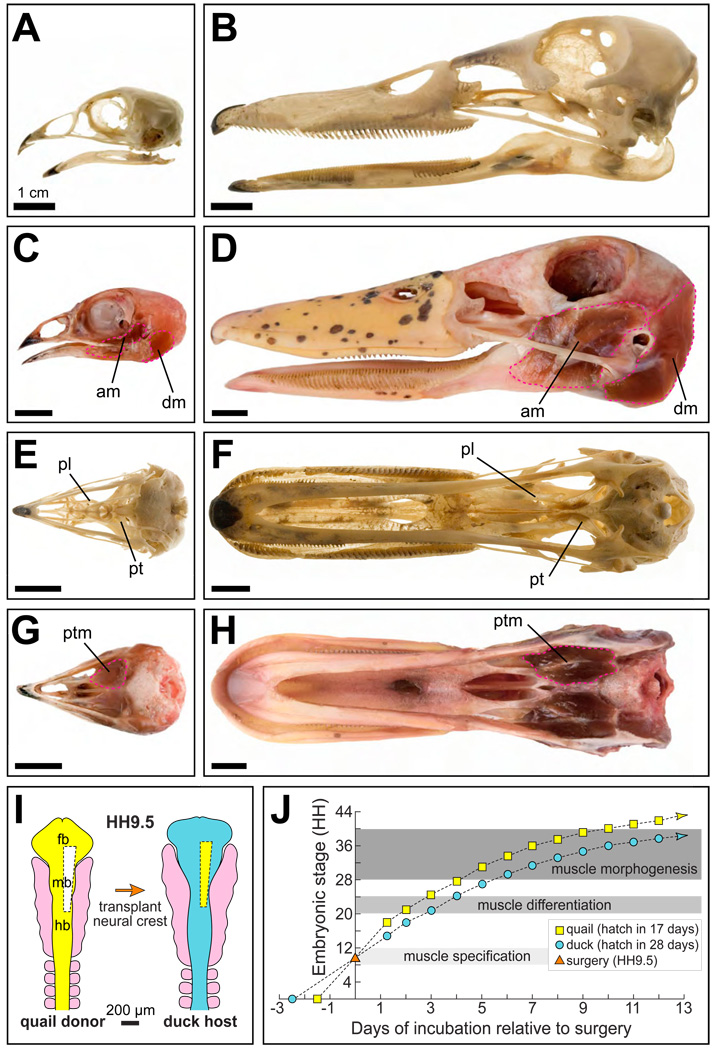

To test our hypothesis we employed the quail-duck chimeric system (Lwigale and Schneider, 2008). Quail and duck display unique jaw morphologies in conjunction with their particular feeding habits (Fig. 1A–1H). Quail are peckers whereas duck are strainers (Soni, 1979; Zweers, 1974; Zweers et al., 1977), and this behavioral dichotomy is reflected in the size, shape, and attachment sites of their skeletal elements and muscles (Fig. 1A–1H). This allows quail-duck chimeras (“quck”) to reveal the extent to which quail donor neural crest mesenchyme can impart species-specific pattern on duck host jaw muscles. Another valuable feature of this chimeric system is that quail embryos mature at a considerably faster rate than do duck embryos (Fig. 1J) and donor cells maintain their intrinsic timetable within a host (Eames and Schneider, 2005; Eames and Schneider, 2008; Merrill et al., 2008; Schneider and Helms, 2003). This offers a straightforward way to identify mechanisms through which neural crest mesenchyme potentially regulates myogenesis—simply by screening for donor-induced changes to the onset of gene expression or other events in the host.

Figure 1.

Quail-duck chimeric system to study jaw muscle development. (A) Head skeleton of adult Japanese quail in lateral view. (B) Head skeleton of adult white Pekin duck. (C) Quail head with jaw muscles (pink dashed lines). (D) Duck head with jaw muscles. (E) Quail head skeleton in ventral view. (F) Duck head skeleton. (G) Quail head with jaw muscles. (H) Duck head with jaw muscles. (I) To generate “quck” chimeras, unilateral populations of cranial neural crest cells were excised from quail donors at Hamburger and Hamilton (HH) stage 9.5 and transplanted in place of duck neural crest. (J) Growth curves of quail and duck embryos. Although quail and duck embryos were stage-matched for surgery at HH9.5, they progressively departed in stage due to their different maturation rates. Embryos were analyzed during muscle specification, differentiation, and morphogenesis. Abbreviations: am, mandibular adductor muscle; dm, mandibular depressor muscle; fb, forebrain; hb, hindbrain; mb, midbrain; pl, palatine bone; pt, pterygoid bone; ptm, pterygoid muscle.

Our results demonstrate that neural crest mesenchyme provides species-specific patterning information to the jaw muscles. The first arch contains jaw closing muscles (i.e., mandibular adductor, pseudotemporal, and pterygoid), and jaw opening muscles (i.e., protractor of the quadrate) (McClearn and Noden, 1988). In chimeric quck, duck host first arch muscles become shaped and attached like those of quail. To understand how this feat is accomplished on the molecular level, we analyzed expression of genes known to play a role during each stage of myogenesis. While we do not observe neural crest-mediated alterations to the timing of muscle specification or differentiation, we do find spatiotemporal changes in expression of genes associated with the formation of skeletal and muscular connective tissues, which ultimately affect muscle shape and attachment sites. We conclude that species-specific patterning of jaw musculature is mechanistically coupled to evolutionary modifications in morphogenetic programs for neural crest-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues.

Materials and Methods

Generation of chimeric embryos

Fertilized eggs (AA Lab Eggs, Inc.) of Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) and white Pekin duck (Anas platyrhynchos) were incubated at 37°C. Embryos were matched at stage 9.5 by applying the Hamburger and Hamilton (HH) staging system (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951) to quail and duck (Lwigale and Schneider, 2008). Eggs were windowed and embryos visualized with Neutral Red (Sigma). Unilateral populations of neural crest cells from the caudal forebrain to the second rhombomere of the rostral hindbrain were grafted orthotopically from quail to duck (Fig. 1I). Tungsten needles and Spemann pipettes were used for surgical operations (Schneider, 1999). Donor tissue was inserted into a host that had an equivalent region of tissue excised. After surgery, eggs were incubated until reaching appropriate stages.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed in Serra’s (100% ethanol:37% formaldehyde:glacial acetic acid, 6:3:1) overnight at 4°C, paraffin embedded, and cut into 10 µm sections. Representative sections were stained with Milligan’s Trichrome (Presnell et al., 1997) for visualization of cartilage, bone, and muscle. Three-dimensional images of first arch jaw muscles and portions of associated skeletal elements were generated via reconstruction of serial sections using the WinSurf software package (SURF driver, Hawaii).

To detect quail cells in chimeric embryos, sections were immunostained with the quail nuclei-specific Q⊄PN antibody (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)) (Schneider, 1999). Detection of myosin heavy chain was carried out on sections using monoclonal antibody A4.1025 (1:50, DSHB). For whole-mount myosin heavy chain staining, embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with MF20 monoclonal antibody (1:100, DSHB) (Klymkowsky and Hanken, 1991).

Gene expression analyses

Sections adjacent to those used for histological and immunohistochemical analyses were processed for in situ hybridization (Albrecht et al., 1997) with 35S-labeled chicken riboprobes to genes expressed in myocytes or their precursors (Tbx1, Capsulin, Myf5, and MyoD); in chondrocytes or their precursors (Sox9 and Col2); in osteocytes or their precursors (Runx2); and in tenocytes as well as epi- and endomysial cells or their precursors (Scx and Tcf4). Sections were counterstained with a fluorescent blue nuclear stain (Hoechst; Sigma).

Results

Neural crest mesenchyme establishes species-specific jaw muscle morphology

To test the ability of neural crest mesenchyme to provide species-specific pattern to the jaw musculature, we transplanted unilateral pre-migratory populations of cranial neural crest cells between stage-matched quail and duck embryos (Fig. 1I). This experimental approach maintained a non-surgical side as an internal control (Eames and Schneider, 2005; Eames and Schneider, 2008; Merrill et al., 2008; Tucker and Lumsden, 2004), and provided for an unambiguous comparison between quail donor- and duck host-mediated muscle patterning in the same chimeric embryo. A further analytical tool was the significant divergence in growth rates between quail and duck. Within two days after surgery and then consistently throughout the rest of the developmental period analyzed, quail donor cells remained approximately three embryonic (HH) stages ahead of the duck host, reflecting the different maturation rates of control quail and duck embryos (Fig. 1J).

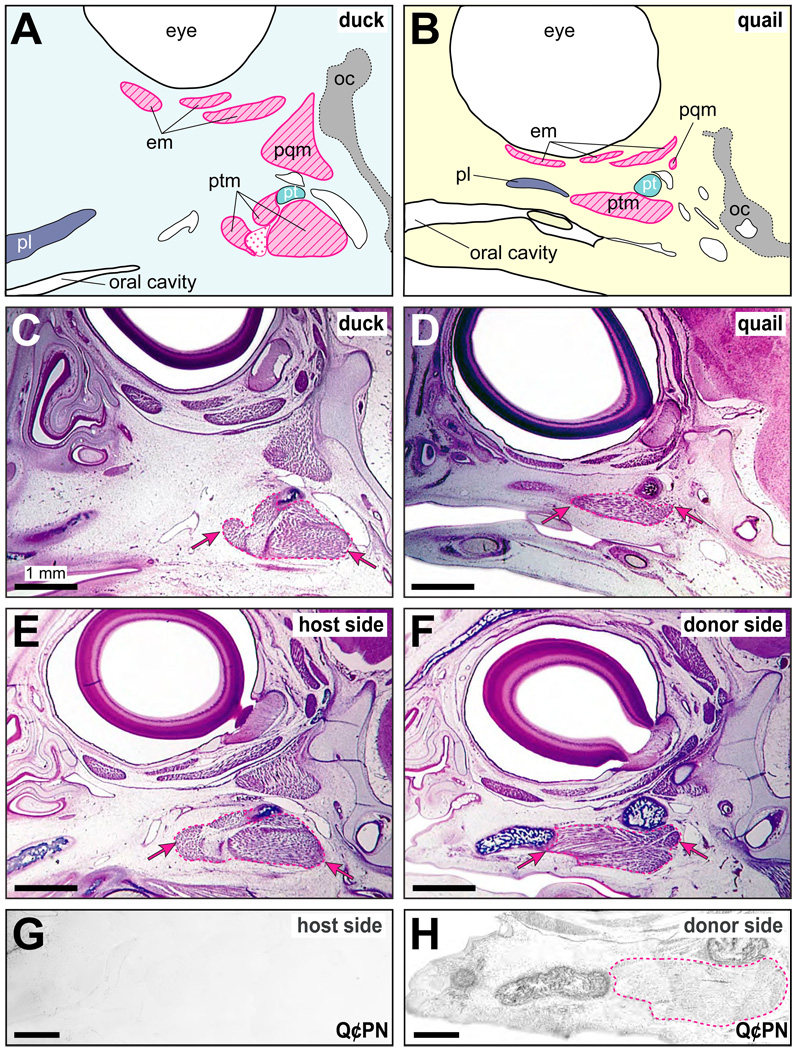

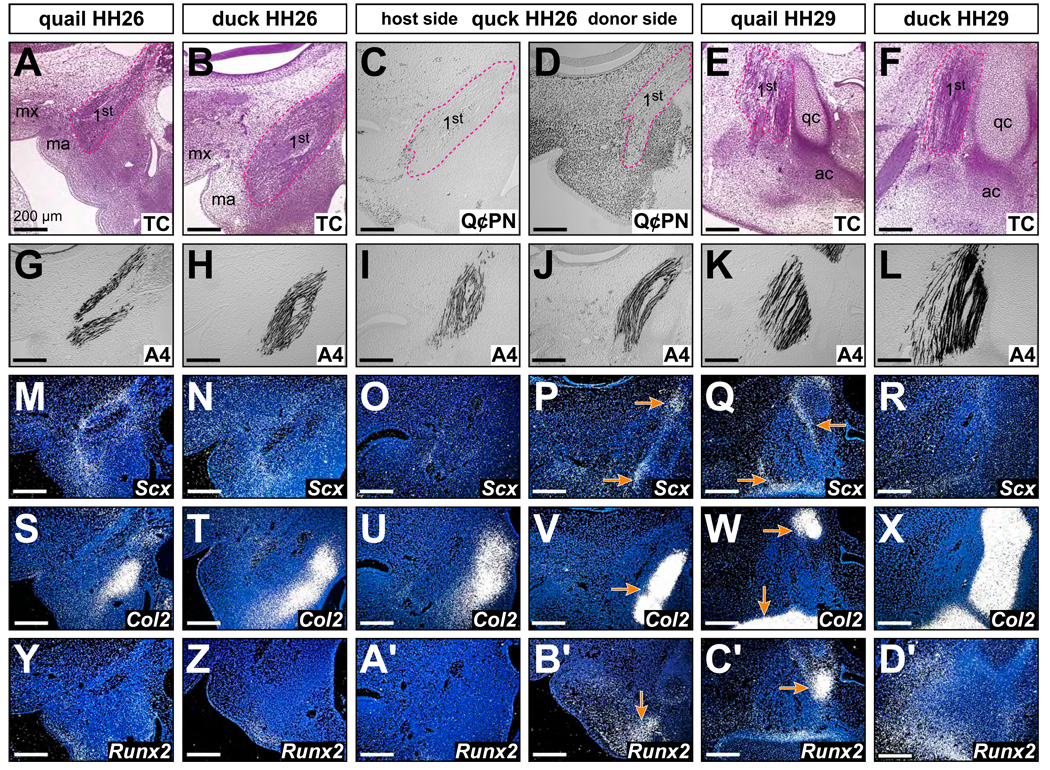

The architecture of first arch jaw muscles differed greatly between adult quail and duck (Fig. 1C, 1D, 1G, 1H). Histological sections revealed that these differences were also apparent in quail and duck embryos (Fig. 2A–D). For example, the spatial relationships among the pterygoid muscle, which is the most medial jaw muscle, and the palatine and pterygoid bones (Fig. 1E, 1F), to which the pterygoid muscle attaches were quite dissimilar. By HH36, the duck pterygoid muscle was thick and connected to the caudally located pterygoid bone, whereas in quail, this muscle was relatively thin and elongated much more rostrally towards the palatine bone. In chimeric quck, the host side maintained an equivalent spatial relationship among the pterygoid muscle and the palatine and pterygoid bones to that observed in control duck (Fig. 2E). However, we observed striking changes to the musculoskeletal morphology on the donor sides of quck. For example, the pterygoid muscle as well as the palatine and pterygoid bones were transformed to resemble those present in control quail (Fig. 2F). Staining adjacent sections with the anti-quail Q⊄PN antibody confirmed that large amounts of quail cells were present on the donor sides, particularly throughout the skeletal and muscular connective tissues, whereas few to no quail cells were detected on the host sides (Fig. 2G, 2H).

Figure 2.

Jaw muscle morphology in quail, duck, and chimeric quck embryos. (A) Schematic of control duck at HH36 showing spatial relations among the jaw muscles and skeleton in sagittal section. (B) Schematic of a control quail at HH36. (C) Histological section of a control duck. Note the robust rhomboidal shape of the pterygoid muscle (pink dashed line and arrows), which is the most medial first arch jaw muscle. (D) Equivalent section of a control quail. Note the flattened and elongated shape of the pterygoid muscle and its topological relationships to the palatine and pterygoid bones. (E) The host side of chimeric quck is equivalent to that seen in control duck. (F) The donor side of chimeric quck is like that found in control quail, especially the shape of the pterygoid muscle and its relations to the palatine and pterygoid bones. (G) The duck host side of quck does not contain quail donor cells (i.e., Q⊄PN-negative). (H) In contrast, quail cells (i.e., Q⊄PN-positive) are found throughout the jaw region, and in connective tissues around the host pterygoid muscle on the donor side. Abbreviations: em, eye muscles; oc, orbital cartilage; pl, palatine bone; pqm, protractor of the quadrate muscle; pt, pterygoid bone; ptm, pterygoid muscle.

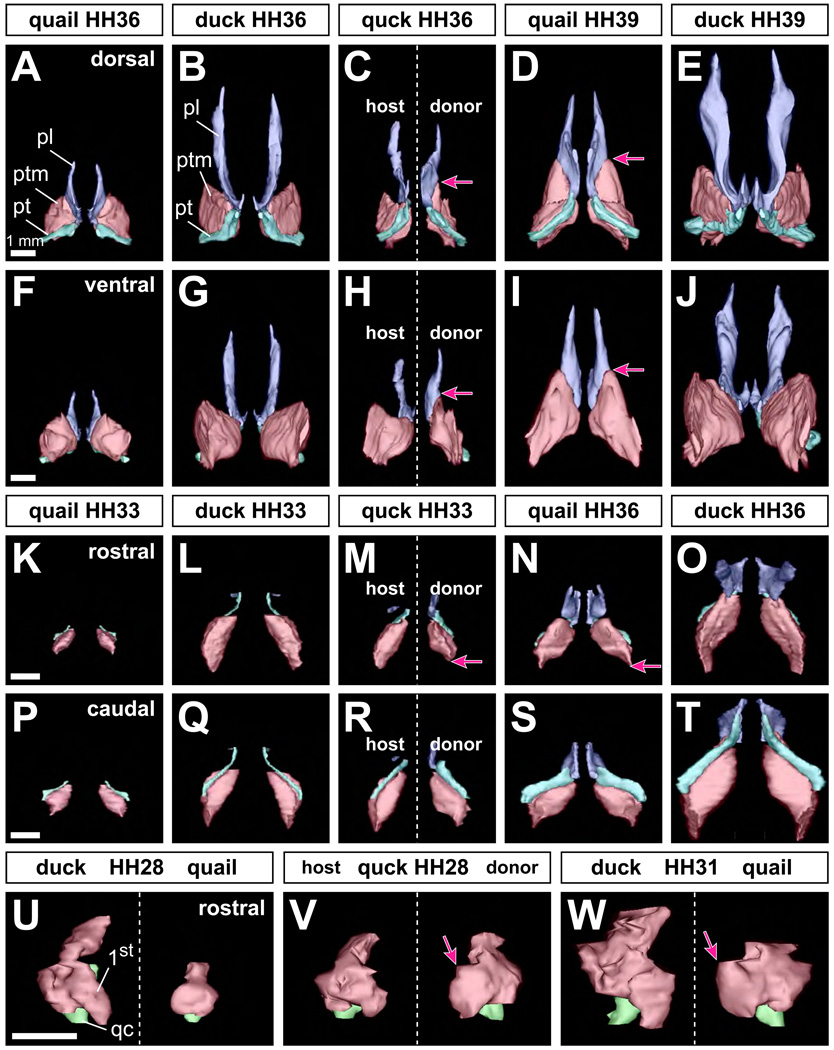

To evaluate in further detail the effects of cranial neural crest mesenchyme on jaw muscle size and shape, we generated and compared three-dimensional reconstructions of first arch muscles and their associated skeletal elements across several stages of quail, duck, and chimeric quck. We found that jaw muscle size and shape were consistently different between control quail and duck. Within these control embryos the left and right sides were always equivalent and symmetrical. In contrast, the donor sides of chimeric quck contained jaw muscles that were significantly transformed in shape and attachment sites to resemble those of an older quail (n=16). For example, in HH36 quail, the dorso-medial part of the pterygoid muscle was elongated rostrally and almost reached the midpoint of the palatine bone (Fig. 3A, 3F). In duck embryos at the same embryonic stage, the dorso-medial portion of the pterygoid muscle never projected rostrally and this muscle did not approach the palatine bone dorsally (Fig. 3B, 3G). In HH39 quail, the pterygoid muscle was larger overall and relatively thinner and flatter than that in HH36 quail (Fig. 3D, 3I). Moreover, the rostral projection of the dorso-medial part of the muscle was more pronounced. The quail pterygoid muscle was also attached to the palatine bone more broadly. In HH39 duck, the shape of the pterygoid muscle was similar to that at HH36, although the size of the muscle was substantially increased (Fig. 3E, 3J). In HH36 quck, a clear asymmetry was observed between the host and donor sides. Specifically, the more rostral position of the attachment sites and the shape of the pterygoid muscle on the donor side more closely resembled that of an HH39 quail, while the host side looked like the duck control at HH36 (n=9, Fig. 3C, 3H). Muscle size was roughly equivalent to that found on the host side and in HH36 duck controls.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional reconstructions of the first arch jaw complex in quail, duck, and chimeric quck embryos. (A, B) Spatial relations among the palatine bone (pl; blue), pterygoid bone (pt; aqua), and pterygoid muscle (ptm; pink) are shown in dorsal view of control quail and duck at HH36. (C) Dorsal view of the duck host (left side) and quail donor (right side) of a chimeric quck at HH36. Note the asymmetry in musculoskeletal morphology, especially the rostral extension of the pterygoid muscle (pink arrow) like that seen in control quail at HH39. (D, E) Dorsal view of quail and duck at HH39. (F, G) Ventral view at HH36. (H) Ventral view of a quck at HH36. (I, J) Ventral view at HH39. (K, L) Rostral view at HH33. (M) Rostral view of a quck at HH33. Note the asymmetry in shape especially that the muscle is reduced in height (pink arrow) like that seen in control quail at HH36 (pink arrow). (N, O) Rostral view at HH36. (P, Q) Caudal view at HH33. (R) Caudal view of a quck at HH33. (S, T) Caudal view at HH36. (U) Rostral view of first arch (1st) jaw muscles and quadrate cartilage (qc; green) of control duck (left column) and quail (right column) at HH28. (V) Rostral view of a quck at HH28. Note the robust extension of the pterygoid muscle on the donor side like that seen in control quail at HH31. (W) Rostral view of duck and quail at HH31.

To discern the steps through which these species-specific differences in jaw muscle morphology arose we examined earlier embryonic stages. In HH33 quck, jaw muscles on the donor side were distinct from those on the host side and resembled the shape of that observed in control quail at HH36 especially in terms of their overall height (n=2, Fig. 3K–3T). In quail at HH28, the medial portion of the first arch jaw muscle mass was thicker compared to the corresponding part in HH28 duck (Fig. 3U). In HH28 quck, the muscle mass on the host side was unchanged from that of control duck at equivalent stages, whereas the shape was considerably altered on the donor side like that seen in control quail embryos (n=5; Fig. 3V). The medial portion of the muscle was thicker and the rostro-medial projection was more conspicuous on the donor side. By using the quadrate cartilage as a landmark, we could observe that the angle of the muscle projection was nearly equivalent to that seen in control quail embryos at HH31 rather than at HH28 (Fig. 3W). The size of the muscle on the donor side was like that on the host side and in control duck at HH28.

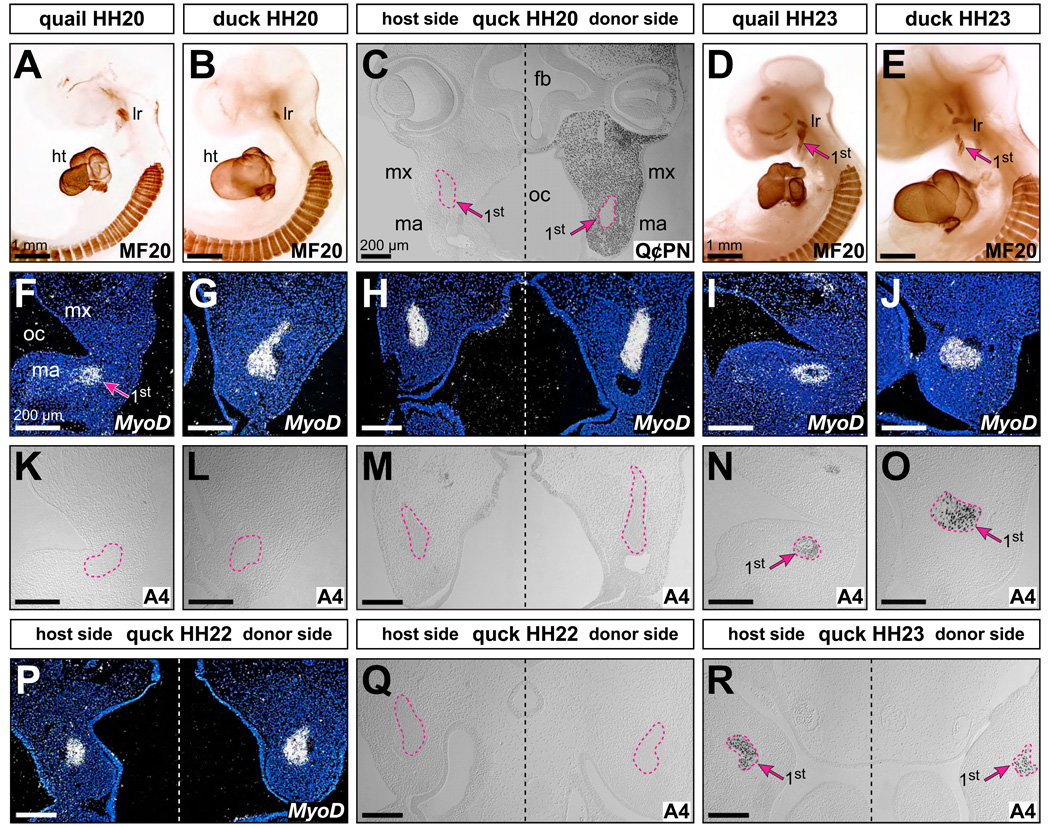

Neural crest mesenchyme does not set the timing of muscle differentiation or specification

To understand the developmental basis for the morphological transformations observed in the jaw muscles of chimeric quck, we evaluated the extent to which neural crest mesenchyme influenced the differentiation and specification of paraxial mesoderm. We used immunohistochemistry to examine the onset of myosin heavy chain synthesis in the first arch jaw muscle primordia of quail, duck, and quck chimeras. Myosin is a structural protein in skeletal muscle and its synthesis is indicative of differentiated myofibers (Noden et al., 1999). If neural crest mesenchyme regulates the timing of muscle differentiation, then the program of myogenesis in quck should follow the quail donor schedule and be accelerated by three stages in the duck host, similar to what we have observed for quck beaks (Schneider and Helms, 2003), feathers (Eames and Schneider, 2005), jaw bones (Merrill et al., 2008), and jaw cartilages (Eames and Schneider, 2008).

First arch muscles of neither quail nor duck had differentiated at HH20 based on the presence of myosin heavy chain (n=3; Fig. 4A, 4B). Instead, myosin heavy chain was detected in jaw muscle precursors of quail and duck at HH23 (Fig. 4D, 4E). In sections of quail and duck at HH20, no myosin heavy chain was detected despite MyoD-positive domains in the first arch muscle mass (n=2; Fig. 4F, 4G, 4K, 4L). In chimeric quck at HH20, with large amounts of quail-derived donor mesenchyme throughout the first arch and especially surrounding the MyoD-expressing muscle core (Fig. 4C, 4H), we observed no myosin heavy chain on either the host or donor side (n=6; Fig. 4M). Myosin heavy chain, however, was observed at HH23 in quail and duck adjacent to MyoD-expressing cells (n=2; Fig. 4I, 4J, 4N, 4O). We also analyzed quck at HH22 (n=2; Fig. 4P, 4Q) and HH23 (n=2; Fig. 4R), and only observed myosin heavy chain staining at HH23. Thus, muscle differentiation followed along the normal timetable of the duck host and was not accelerated by quail donor mesenchyme.

Figure 4.

Neural crest-independent differentiation of first arch muscle. (A, B) Whole-mount HH20 quail and duck embryos in lateral view, stained with MF20 antibody against myosin heavy chain as a marker for muscle differentiation. No jaw muscles have begun to differentiate, whereas the somites, heart (ht), and lateral rectus (Ir) eye muscle have. (C) Frontal section of an HH20 quck stained with Q⊄PN antibody, showing quail donor-derived neural crest mesenchyme (black dots) around unlabeled duck host-derived first arch (1st) jaw muscles (pink dashed lines and arrows). (D, E) Whole-mount HH23 quail and duck embryos stained with MF20. Note the differentiation of first arch jaw muscles (arrows). (F, G, H) MyoD gene expression in jaw muscle precursors of quail, duck, and quck embryos at HH20. (I, J) MyoD expression in HH23 quail and duck. (K, L) In quail and duck embryos at HH20, myosin heavy chain synthesis has not yet begun in jaw muscles as detected with A4.1025 antibody. (M) Despite the presence of large amounts of quail neural crest mesenchyme on the donor side, myosin heavy chain is not detected in quck at HH20 (i.e., A4.1025-negative). (N, O) At HH23, myosin heavy chain (i.e., A4.1025-positive black staining) can be detected in control quail and duck (arrow). (P) First arch jaw muscles in HH22 quck express MyoD. (Q) But myosin heavy chain is not detected in quck at HH22 (i.e., A4.1025-negative). (R) Only in HH23 quck do first arch muscles begin differentiating as indicated by myosin heavy chain (i.e., A4.1025-positive black staining), which is the same stage as in control duck and quail embryos.

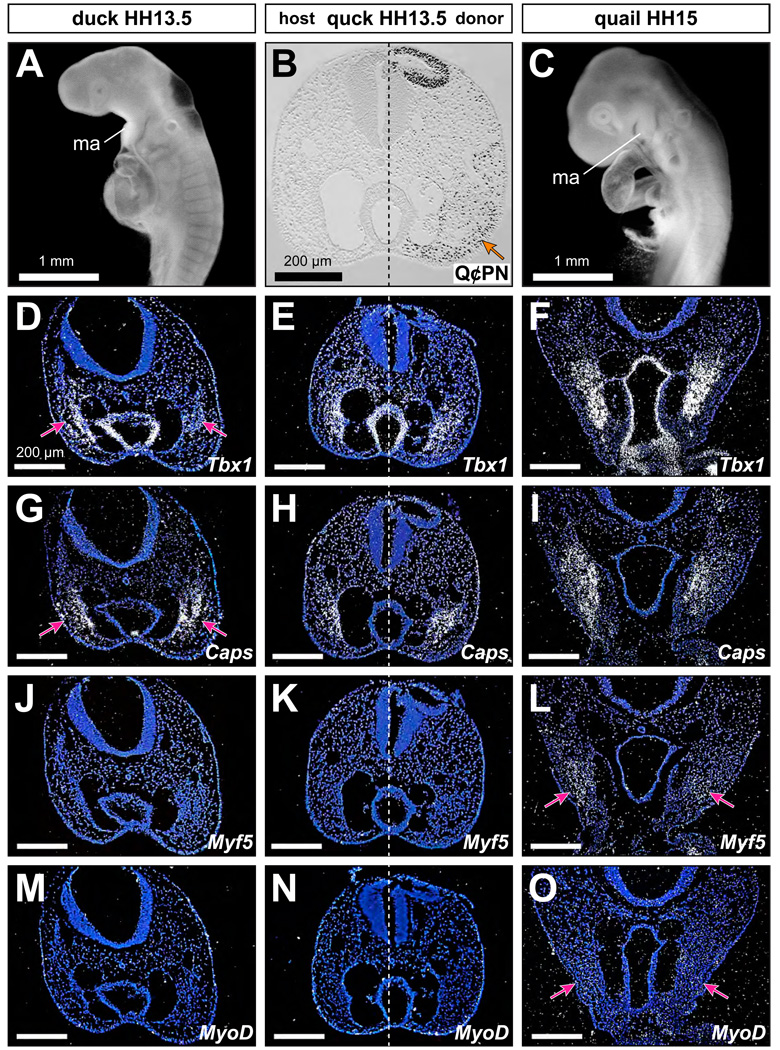

To assay for donor-induced changes to host molecular programs underlying myogenic specification, we performed in situ hybridization with probes for Tbx1, Capsulin, Myf5, and MyoD at HH13.5 through HH16. Tbx1 and Capsulin were strongly expressed by jaw muscle precursors in stages prior to HH15 (Fig. 5D, 5F, 5G, 5I). Similar to previous reports (Noden et al., 1999), Myf5 and MyoD were not expressed at HH13.5 but were detected in first arch muscle precursors by HH15, in both quail and duck (Fig. 5J, 5L, 5M, 5O). When we analyzed quck at HH13.5, we observed no premature induction of Myf5 or MyoD in the jaw muscle progenitors despite large amounts of adjacent quail donor-derived mesenchyme (Fig. 5B, 5K, 5N). Tbx1 and Capsulin, which were already expressed in controls at HH13.5, were detected on both host and donor sides of quck (n=5; Fig. 5E, 5H). Thus, we observed no donor-mediated changes to the temporal expression patterns of these genes.

Figure 5.

Neural crest-independent regulation of first arch muscle specification. (A) Duck embryo at HH13.5 in lateral view. Note the location of the first (mandibular) arch (ma). (B) Frontal section through the first arch of a quck at HH13.5 stained with Q⊄PN. Note quail donor-derived mesenchyme (i.e., Q⊄PN-positive) surrounding the duck host-derived muscle core (arrow). (C) Quail embryo at HH15. (D) Tbx1 expression in jaw muscle precursors (arrows) of a duck at HH13.5. (E) Tbx1 expression in quck at HH13.5. Note that Tbx1 is strongly expressed on both donor and host sides. (F) Tbx1 expression in quail at HH15. (G) Capsulin (Caps) expression in jaw muscle precursors (arrows) of a duck at HH13.5. (H) Caps expression in a quck at HH13.5. Note that Caps is strongly expressed on both donor and host sides. (I) Caps expression in a quail at HH15. (J) Myf5 is not yet expressed in jaw muscle precursors of duck at HH13.5. (K) Myf5 is also not expressed in jaw muscle precursors of quck at HH13.5, despite the presence of quail donor-derived neural crest mesenchyme. (L) Myf5 is expressed in quail by HH15 (arrows). (M) MyoD is not yet expressed in jaw muscle precursors of duck at HH13.5. (N) MyoD is also not expressed in the jaw muscle precursors of quck at HH13.5, despite the presence of quail donor-derived neural crest mesenchyme. (O) MyoD is just beginning to be expressed at low levels in the first arch muscles of quail at HH15 (arrows).

Neural crest-derived muscle connective tissues execute autonomous molecular programs

To assay for molecular changes in neural crest-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues that could be associated with the species-specific patterning of muscle, we analyzed spatiotemporal expression patterns of Tcf4, Sox9, Runx2, Col2, and Scx in quail, duck, and quck chimeras.

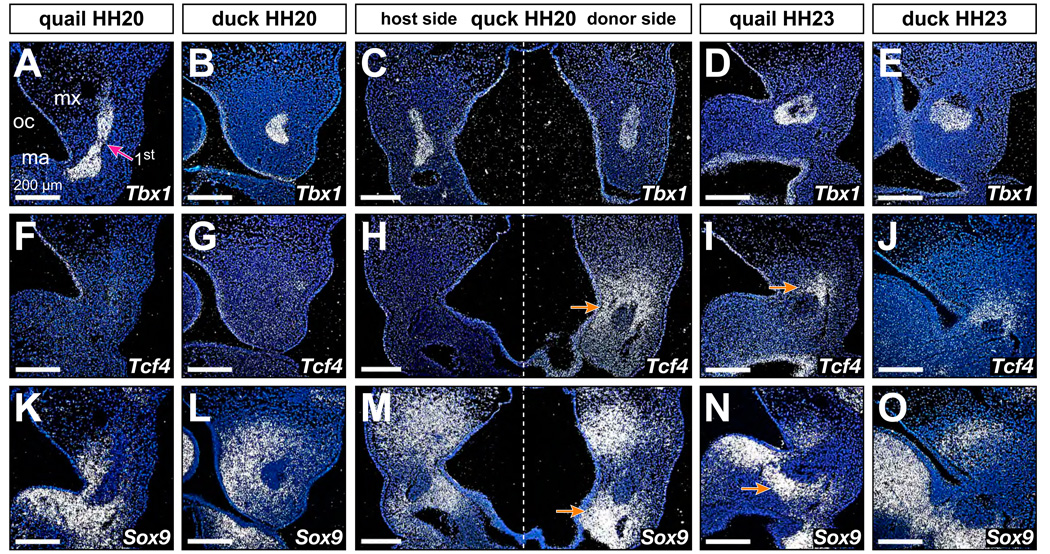

At HH20, Tcf4 was observed in a wide variety of domains including the limbs, somites, heart, and central nervous systems, yet Tcf4 was not detected in first arch mesenchyme of quail (Fig. 6F) and duck (Fig. 6G). However, by HH23, Tcf4 was expressed highly and broadly in neural crest mesenchyme surrounding the first arch muscle mass of both quail and duck (Fig. 6I, 6J). On the host side of quck at HH20, Tcf4 expression was not observed in the mesenchyme, but on the contra-lateral donor side, Tcf4 expression was strongly up-regulated in quail-derived mesenchyme surrounding Tbx1-expressing first arch muscle (n=6; Fig. 6H). Levels of Tcf4 expression were comparable to those found in control quail and duck embryos at HH23 (Fig. 6I and 6J). Sox9 was expressed broadly throughout the mesenchyme around first arch muscles in quail and duck at HH20 (Fig. 6K and 6L). By HH23, Sox9 levels were higher and the domains more restricted to areas destined to form cartilage (Fig. 6N and 6O). In quck at HH20, Sox9 expression on the host side resembled that of duck at HH20, whereas the donor side was up-regulated in a more limited domain (Fig. 6M).

Figure 6.

Neural crest mesenchyme autonomously executes molecular programs for skeletal and muscular connective tissues. (A–E) Frontal sections through the oral cavity (oc), and maxillary (mx) and mandibular (ma) primordia of quail, duck, and quck showing Tbx1 expression in presumptive first arch (1st) jaw muscles. (F, G) In control quail and duck embryos at HH20, Tcf4 expression is not detected in first arch mesenchyme. (H) Tcf4 is also not observed on the host side of quck at HH20. However, on the contra-lateral donor side of the same chimeric embryo, coincident with a large amount of quail-derived mesenchyme (see Figure 4, panel C), Tcf4 is strongly expressed around jaw muscle precursors (arrow). (I, J) These higher expression levels and patterns are observed in quail (arrows) and duck at HH23. (K, L) In control quail and duck embryos at HH20, Sox9 is expressed throughout first arch mesenchyme. (M) Sox9 is detected at higher levels and in a more restricted spatial domain on the donor side of quck at HH20 (arrow). (N, O) Similar expression patterns for Sox9 are observed in quail and duck at HH23 (arrow).

Expression of Scx was observed in diffuse domains along the jaw muscles at HH26 (Fig. 7M, 7N). By HH29, Scx expression was up-regulated and restricted to sites of presumptive tendon located between jaw muscles and their supporting skeleton such as the articular cartilage (Fig. 7Q, 7R). Scx expression in quck was altered in association with quail donor mesenchyme (Fig. 7D). On the host side of HH26 quck, Scx expression was diffuse and equivalent to that observed in control duck (Fig. 7O), but on the donor side, Scx was up-regulated and restricted around the jaw muscles (Fig. 7P). Similarly, we observed up-regulation of Col2 in presumptive cartilage (Fig. 7S–7X) and Runx2 in presumptive bone on the donor side of quck at HH26 like that observed at HH29 (Fig. 7Y, 7Z, 7A’–7D’).

Figure 7.

Neural crest mesenchyme autonomously executes molecular programs for skeletal and muscular connective tissues. (A, B) Sagittal histological sections through maxillary (mx) and mandibular (ma) primordia of quail and duck at HH26 stained with Trichrome (TC) showing first (1st) arch muscles (pink dashed line). (C, D) Sections showing host and donor sides of a quck at HH26 stained with anti-quail (Q⊄PN) antibody. Note that few quail cells are found on the host side whereas many quail cells are distributed throughout skeletal and muscular connective tissues on the donor side. (E, F) Sections of quail and duck at HH29. The quadrate (qc) and articular (ac) cartilages of the jaw are clearly visible. (G–L) Myosin heavy chain as detected with A4.1025 antibody. (M, N) Diffuse expression of Scx in neural crest-derived first arch mesenchyme. (O) Similarly diffuse expression is observed on the host side of quck. (P) In contrast, Scx is up-regulated on the donor side of quck coincident with the presence of quail-derived neural crest mesenchyme. Moreover, this domain is restricted to the boundary between the jaw skeleton and the muscles (arrows). (Q, R)Scx is highly expressed and restricted to presumptive tendons by HH29 in quail (arrows) and duck. (S–X)Col2 expression in presumptive jaw cartilage. Note the up-regulation of Col2 on the donor side of HH26 quck like that observed in HH29 quail (arrow). (Y-D’) Runx2 expression in presumptive jaw bone. Note up-regulation of Runx2 on the donor side of HH26 quck like that observed in HH29 quail (arrow).

Discussion

Cranial neural crest mesenchyme regulates species-specific jaw muscle pattern

The ability of neural crest mesenchyme to regulate cranial muscle development has been known for more than half a century. For example, neural crest extirpations in amphibian embryos disrupted jaw muscle architecture (Ericsson et al., 2004; Hall, 1950; Olsson et al., 2001). In experiments using avians, the musculoskeletal anatomy of the second arch (i.e., hyoid) was transformed into that of the first arch (i.e., mandibular) simply by exchanging premigratory second and first arch neural crest (Noden, 1983b). Zebrafish mutants revealed that defects in cranial neural crest secondarily affect the differentiation of jaw muscles (Schilling et al., 1996). When Hoxa2, a gene normally expressed in neural crest mesenchyme and required for second arch identity, was expressed ectopically throughout the jaw primordia of either Xenopus or chick embryos, jaw muscle morphology was transformed homeotically (Grammatopoulos et al., 2000; Pasqualetti et al., 2000). While such studies have provided important insights on the role of neural crest cells during muscle differentiation and morphogenesis, precise mechanisms through which such re-patterning occurs, or the extent to which neural crest cells influence the generation of species-specific jaw muscle morphology, have not been comprehensively investigated.

In contrast, our study demonstrates that neural crest mesenchyme is the source of species-specific jaw muscle pattern. We detailed jaw muscle anatomy that distinguishes quail from duck embryos and then generated chimeras with quail donor-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues. Quck jaw muscles were transformed in shape to resemble those found in quail, even though these muscles were derived entirely from the duck host. Such alterations were not only species-specific but also stage-specific, in that muscles on the donor side were more similar to those found in control quail three stages later. Thus, neural crest mesenchyme directs patterning and morphological integration of the first arch musculoskeletal complex.

Cranial muscle histogenesis is regulated independent of muscle morphogenesis

Unlike our previous work on bird beaks and feathers (Eames and Schneider, 2005; Jheon and Schneider, 2009; Schneider, 2005; Schneider and Helms, 2003) in which we show unequivocally that quail donor mesenchyme can accelerate duck host gene expression and histogenic differentiation by three stages, here we find that neural crest mesenchyme does not influence the timing of muscle differentiation. What we would have expected to see in quck if quail donor mesenchyme affected the timing of duck host muscle differentiation is positive myosin heavy chain staining by HH20 (three stages earlier than normal in duck) and premature expression of molecular makers that specify cranial myogenic lineages. Instead, host muscle followed its normal time course for development. We examined Tbx1, which is a T-box-containing transcription factor known for its contributions to the jaw muscle defects in DiGeorge syndrome (Kelly et al., 2004), and which is transcribed in avian cranial paraxial mesoderm as early as HH7 (Bothe and Dietrich, 2006; Dastjerdi et al., 2007). We also analyzed Capsulin, which encodes a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor and regulates first arch muscle development through its actions with another bHLH transcription factor, MyoR (Lu et al., 2002). Capsulin is expressed in the developing jaw musculature of chick embryos around HH10 (von Scheven et al., 2006b). Because these genes were already expressed in cranial paraxial mesoderm of quail and duck prior to and at the time of surgery (HH9.5), we did not expect, nor did we observe, any changes to their expression by quail donor mesenchyme.

Similarly Myf5 and MyoD, which are bHLH transcription factors required for the specification of skeletal myoblasts (Rudnicki and Jaenisch, 1995; Rudnicki et al., 1993; Tajbakhsh and Buckingham, 2000), and which are expressed in first arch mesoderm of chicks by HH15 (Noden et al., 1999), appear to be unaffected by faster-developing quail donor mesenchyme. Moreover, because Myf5 and MyoD are required to advance production of muscle structural proteins and permit the assembly of myofibers (Buckingham, 2001; Molkentin and Olson, 1996), the temporal self-governance of the muscle specification program appears to carry forward to the process of muscle differentiation. This is supported by the fact that we did not observe any neural crest-induced changes to the timing of myosin heavy chain synthesis.

In contrast to our results, other experimental evidence suggests that certain aspects of head muscle specification and differentiation are indeed neural crest-dependent. For example, in zebrafish chinless mutants, the skeletal fates of cranial neural crest cells are perturbed and this phenotype is accompanied by first arch jaw muscles that are specified but fail to differentiate (Schilling et al., 1996). Also, muscle differentiation does not occur properly when neural crest mesenchyme is mis-regulated or absent (Rinon et al., 2007). Undoubtedly, muscle histogenesis is a complex process that involves numerous gene regulatory networks, reciprocal signaling interactions, and multiple hierarchical levels of control. We merely focused on one aspect, which is the timing of muscle specification and differentiation, where neural crest mesenchyme does not seem to play a role. This does not preclude the distinct possibility that neural crest mesenchyme influences other aspects of muscle histogenesis. Thus, our results are consistent with the notion that the myogenic molecular program is regulated by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Bothe et al., 2007; von Scheven et al., 2006a). But since we could not point to changes in the timing of myogenic specification or differentiation to explain the morphological transformations observed in chimeric quck, we looked for alterations in expression of genes associated with the formation of skeletal and muscular connective tissues.

Neural crest-derived connective tissues provide species-specific jaw muscle pattern

Signaling between muscle connective tissues and muscle is essential for generating musculoskeletal morphology. For example during limb development, muscle pattern is established by interactions between lateral plate mesoderm, which gives rise to the appendicular skeleton and associated muscle connective tissues, and somitic mesoderm, which generates skeletal muscle (Kardon, 1998; Kardon et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Guzman et al., 2007). Moreover, lateral plate-derived mesenchyme substantially affects the differentiation and morphogenesis of somitic trunk mesoderm (Burke and Nowicki, 2003; Nowicki and Burke, 2000; Winslow et al., 2007). Lateral plate mesoderm and its muscle connective tissue derivatives like tendon and ligament express genes such as Tcf4 and Scx (Edom-Vovard and Duprez, 2004). Tcf4 is a transcription factor that functions downstream of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is indispensable to skeletal muscle development (Anakwe et al., 2003; Bonafede et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2007). Expression of Tcf4 in lateral plate-derived limb mesenchyme determines the spatial pattern of limb skeletal muscles (Kardon et al., 2003), and our experiments suggest that Tcf4 may play a similar role during jaw muscle morphogenesis. The transcription factor, Scx is also a distinct marker for tendon and ligament progenitors and differentiated cells (Cserjesi et al., 1995; Schweitzer et al., 2001). Scx has been well studied in the trunk (Brent et al., 2005; Brent and Tabin, 2004; Shukunami et al., 2006) but less so in the head (Grenier et al., 2009; Pryce et al., 2007). Tendon differentiation is disrupted in Scx−/− mice (Murchison et al., 2007).

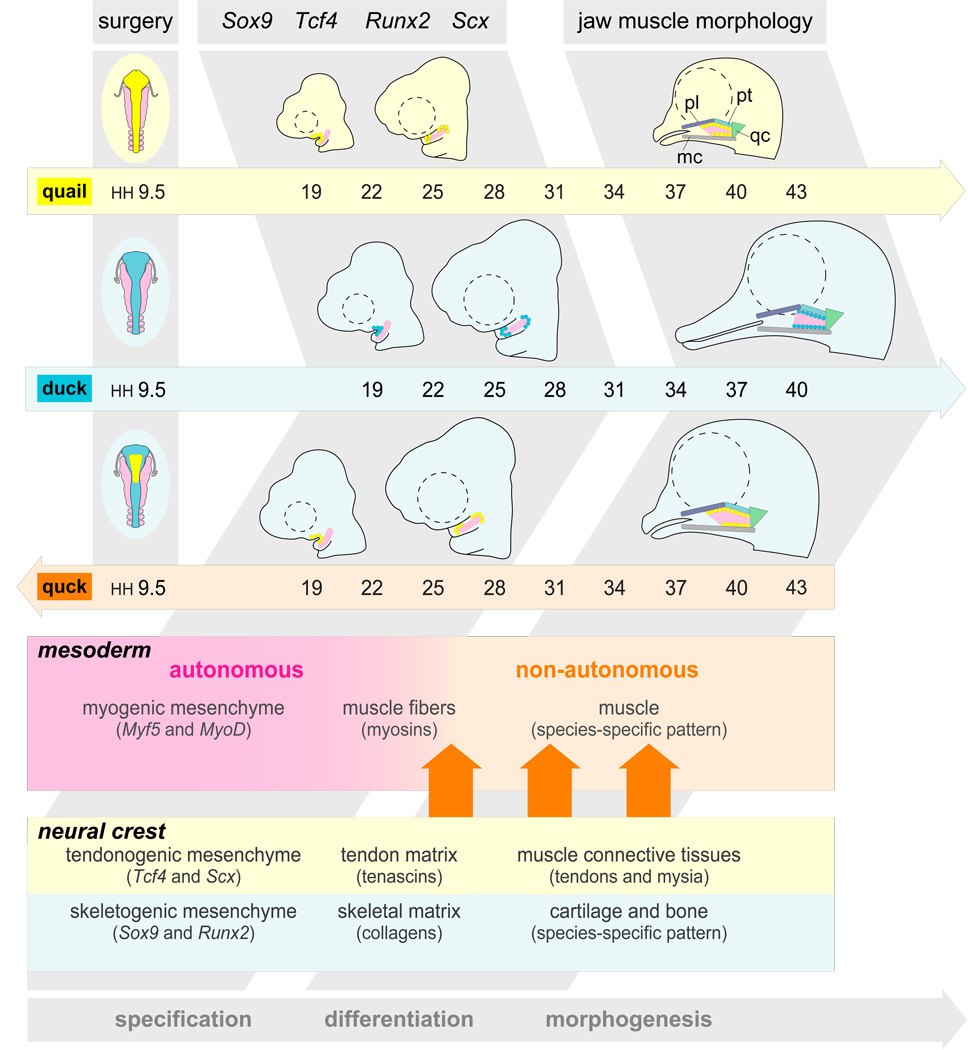

Our analyses confirm that Tcf4 and Scx are dynamically expressed in jaw muscle connective tissues and precursor cells, and demonstrate that these genes are regulated by neural crest mesenchyme. We observed diffuse Scx expression in the connective tissues surrounding the jaw muscle mass on the host side, and up-regulated expression along the musculoskeletal junction on the donor side. Similarly, Tcf4 expression was accelerated and highly restricted on the donor sides of quck around the presumptive jaw muscles. This donor-induced expression of Tcf4 occurred at HH20, and was also accompanied by up-regulation of Sox9 in domains around the first arch muscle mass. By HH22, Sox9 becomes restricted on the donor side to regions where premature cartilage will ultimately form (Eames and Schneider, 2008). Similarly, by HH26 in quck, we observed accelerated Runx2 expression, and these domains correspond to areas destined to form premature bone in quck (Merrill et al., 2008). Based on such findings we propose that by executing autonomous molecular programs, neural-crest-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues convey species-specific patterning information to the jaw muscles (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

A model for the role of neural crest mesenchyme in generating species-specific jaw muscle morphology. Quail (light yellow) and duck (light blue) embryos have distinct jaw muscle morphology. Jaw muscle is derived from cranial paraxial mesoderm (pink) and jaw muscle connective tissue forms from cranial neural crest cells (bright yellow for quail and bright blue for duck). Around HH22, Sox9 and Tcf4 are expressed in restricted domains within first arch neural crest mesenchyme destined to form skeletal and muscular connective tissues (bright yellow circles for quail and bright blue for duck). Subsequently (after HH24), Scx and Runx2 are also up-regulated in mesenchyme surrounding presumptive jaw muscle. These transcription factors are regulated spatiotemporally, according to species-specific developmental programs (bright yellow circles for quail and bright blue circles for duck). In older embryos, Tcf4 is primarily expressed in epi- and endomysial connective tissues of jaw muscle and Scx is expressed in tendons that connect the jaw muscles to skeletal elements including the quadrate (qc) and Meckel’s (mc) cartilages, and the palatine (pl) and pterygoid (pt) bones. In chimeric quck, expression in skeletal and muscular connective tissues follows the donor species, which then determines jaw muscle pattern (large orange arrows). While neural crest-derived skeletal and muscular connective tissues affect muscle shape and attachment sites, they do not appear to influence the timing of muscle specification or differentiation.

While precise molecular mechanisms through which neural crest-derived connective tissues might provide patterning information to jaw muscles are not known, several signaling pathways including Wnt, BMP, and FGF, likely participate by regulating an array of downstream targets. For example, cranial muscle differentiation appears to involve inhibitors from the BMP and Wnt signaling pathways that are secreted by neural crest mesenchyme (Tzahor et al., 2003). Likewise, at least in the trunk and limbs, Scx appears to be regulated primarily by FGFs such as Fgf4 and Fgf8 during the formation of tendon progenitors (Brent et al., 2005; Brent et al., 2003; Brent and Tabin, 2004; Edom-Vovard et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2005). But in the head, many FGFs are not expressed in neural crest-derived jaw mesenchyme; rather their transcripts are found in overlying ectoderm (Mina et al., 2002; Shigetani et al., 2002). Instead, FGF receptors such as Fgfr1, Fgfr2, and Fgfr3, which regulate Scx expression within the somites (Brent and Tabin, 2004), are expressed in mandibular mesenchyme and in condensing cartilage (Havens et al., 2006; Mina et al., 2002; Wilke et al., 1997), and are regulated by neural crest mesenchyme (Eames and Schneider, 2008). Therefore, the implementation of jaw muscle pattern likely involves signaling interactions among a variety of tissues.

Neural crest mesenchyme underlies the evolution of jaw muscle morphology

Evolutionary diversity in jaw muscle morphology can arise by a transposition of attachment sites on skeletal elements, changes in muscle shape, an increase or decrease in the size of individual muscles, and/or modifications in the number of muscles comprising a given complex. Our results reveal that neural crest mesenchyme mediates the first two processes, and in so doing, plays a fundamental mechanistic role in establishing species-specific muscle morphology. However, in terms of influencing muscle size, neural crest mesenchyme appears to have little effect. Analysis of quck chimeras shows that the size of the jaw muscles on the donor side was about equivalent to that found on the host side and not as large as the muscle mass observed in quail embryos three stages later. In contrast, quck muscle shape was like that of an older quail. Therefore, muscle size and shape appear to be under separate regulatory control and can likely evolve independently. Several molecular factors influence the size of skeletal muscles. For example, myostatin (Gdf8), is expressed in skeletal muscles (Lee, 2004) and functions as a negative regulator since all myostatin-mutated cattle, dogs, mice, and zebrafish have increased skeletal muscle mass (Amali et al., 2004; McPherron et al., 1997; McPherron and Lee, 1997; Mosher et al., 2007). Myosin protein determines muscle size and there is a correlation between muscle size reduction in humans and mutations in myosin heavy chain genes (Stedman et al., 2004). That we observed no neural crest-dependent changes to the timing of myosin heavy chain synthesis is consistent with the absence of transformations in quck muscle size.

In terms of muscle number, individual jaw muscles are separated from one another by fascia, and embryonically, muscle segregation is achieved by the penetration of neural crest mesenchyme into the muscle progenitor pool (Bogusch, 1986; Francis-West et al., 2003; Noden and Francis-West, 2006). Although we did not detect any in quck, spatiotemporal changes in the migration and/or differentiation of connective tissue precursor cells could potentially lead to variation in the number of jaw muscles like that found in several vertebrate taxa (Friel and Wainwright, 1997; Nakae and Sasaki, 2004; Tokita, 2004; Tokita et al., 2007; Zusi, 1993). Thus, the evolution of jaw muscle size, shape, attachments, and number likely occurs through various morphogenetic processes decoupled from one another in a manner that provides maximum phenotypic plasticity. But at the same time, the capacity of neural crest mesenchyme to orchestrate its genetic programs autonomously, and as a consequence implement muscle pattern across species via its connective tissue derivatives, provides a potent mechanism to explain how the musculoskeletal system remains structurally and functionally integrated during the course of vertebrate evolution.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kristin Butcher, Johanna Staudinger, Angelo Kaplan, Logan Durland, and Maren Caruso for technical assistance; Ralph Marcucio, Brian Eames, Andrew Jheon, Amy Merrill, Christian Mitgutsch, and Christian Solem for insightful discussions and comments on the manuscript. M.T. is grateful to Kiyokazu Agata for encouragement as well as Kazuhiko Satoh and Matthew Brandley for providing useful literature. The A4.1025, MF20, and Q⊄PN antibodies were obtained from DSHB, maintained by University of Iowa under the auspices of the NICHD. Supported by Grants-in-Aid of JSPS Fellowship to M.T. (18002260); and NIDCR R03 DE014795 and R01 DE016402, NIAMS R21 AR052513, and March of Dimes 5-FY04-26 to R.A.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Albrecht UEG, Helms JA, Lin H. Visualization of gene expression patterns by in situ hybridization. In: Daston GP, editor. Molecular and cellular methods in developmental toxicology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Amali AA, Lin CJ, Chen YH, Wang WL, Gong HY, Lee CY, Ko YL, Lu JK, Her GM, Chen TT, Wu JL. Up-regulation of muscle-specific transcription factors during embryonic somitogenesis of zebrafish (Danio rerio) by knock-down of myostatin-1. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:847–856. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anakwe K, Robson L, Hadley J, Buxton P, Church V, Allen S, Hartmann C, Harfe B, Nohno T, Brown AM, Evans DJ, Francis-West P. Wnt signalling regulates myogenic differentiation in the developing avian wing. Development. 2003;130:3503–3514. doi: 10.1242/dev.00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood DR, Choat JH. A Functional-Analysis of Grazing in Parrotfishes (Family Scaridae) - the Ecological Implications. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 1990;28:189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bemis WE, Northcutt RG. Innervation of the Basicranial Muscle of Latimeria-Chalumnae. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 1991;32:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee V, Mukhopadhyay P, Singh S, Johnson C, Philipose JT, Warner CP, Greene RM, Pisano MM. Neural crest and mesoderm lineage-dependent gene expression in orofacial development. Differentiation. 2007;75:463–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2006.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogusch G. On the spatial relationship between fibroblasts and myogenic cells during early development of skeletal muscles. Acta Anat (Basel) 1986;125:225–228. doi: 10.1159/000146167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafede A, Kohler T, Rodriguez-Niedenfuhr M, Brand-Saberi B. BMPs restrict the position of premuscle masses in the limb buds by influencing Tcf4 expression. Dev Biol. 2006;299:330–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borue X, Noden DM. Normal and aberrant craniofacial myogenesis by grafted trunk somitic and segmental plate mesoderm. Development. 2004;131:3967–3980. doi: 10.1242/dev.01276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe I, Ahmed MU, Winterbottom FL, von Scheven G, Dietrich S. Extrinsic versus intrinsic cues in avian paraxial mesoderm patterning and differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2397–2409. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe I, Dietrich S. The molecular setup of the avian head mesoderm and its implication for craniofacial myogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2845–2860. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman RI. Morphological differentiation and adaptation in the Galápagos finches. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Brent AE, Braun T, Tabin CJ. Genetic analysis of interactions between the somitic muscle, cartilage and tendon cell lineages during mouse development. Development. 2005;132:515–528. doi: 10.1242/dev.01605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent AE, Schweitzer R, Tabin CJ. A somitic compartment of tendon progenitors. Cell. 2003;113:235–248. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent AE, Tabin CJ. FGF acts directly on the somitic tendon progenitors through the Ets transcription factors Pea3 and Erm to regulate scleraxis expression. Development. 2004;131:3885–3896. doi: 10.1242/dev.01275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M. Skeletal muscle formation in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:440–448. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AC, Nowicki JL. A new view of patterning domains in the vertebrate mesoderm. Dev Cell. 2003;4:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabuy E, Adriaens D, Verraes W, Teugels GG. Comparative study on the cranial morphology of Gymnallabes typus (Siluriformes : Clariidae) and their less anguilliform relatives, Clariallabes melas and Clarias gariepinus. Journal of Morphology. 1999;240:169–194. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199905)240:2<169::AID-JMOR7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couly GF, Coltey PM, Le Douarin NM. The developmental fate of the cephalic mesoderm in quail-chick chimeras. Development. 1992;114:1–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserjesi P, Brown D, Ligon KL, Lyons GE, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Olson EN. Scleraxis - a Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Protein That Prefigures Skeletal Formation during Mouse Embryogenesis. Development. 1995;121:1099–1110. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastjerdi A, Robson L, Walker R, Hadley J, Zhang Z, Rodriguez-Niedenfuhr M, Ataliotis P, Baldini A, Scambler P, Francis-West P. Tbx1 regulation of myogenic differentiation in the limb and cranial mesoderm. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:353–363. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Sun X, Liu W, Ai D, Klysik E, Lu MF, Hadley J, Antoni L, Chen L, Baldini A, Francis-West P, Martin JF. Pitx2 promotes development of splanchnic mesoderm-derived branchiomeric muscle. Development. 2006;133:4891–4899. doi: 10.1242/dev.02693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames BF, Schneider RA. Quail-duck chimeras reveal spatiotemporal plasticity in molecular and histogenic programs of cranial feather development. Development. 2005;132:1499–1509. doi: 10.1242/dev.01719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames BF, Schneider RA. The genesis of cartilage size and shape during development and evolution. Development. 2008;135:3947–3958. doi: 10.1242/dev.023309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgeworth FH. The cranial muscles of vertebrates. The University Press, Cambridge Eng; 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Edom-Vovard F, Duprez D. Signals regulating tendon formation during chick embryonic development. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:449–457. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edom-Vovard F, Schuler B, Bonnin MA, Teillet MA, Duprez D. Fgf4 positively regulates scleraxis and tenascin expression in chick limb tendons. Dev Biol. 2002;247:351–366. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson R, Cerny R, Falck P, Olsson L. Role of cranial neural crest cells in visceral arch muscle positioning and morphogenesis in the Mexican axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:237–247. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson R, Olsson L. Patterns of spatial and temporal visceral arch muscle development in the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) J Morphol. 2004;261:131–140. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DJ, Noden DM. Spatial relations between avian craniofacial neural crest and paraxial mesoderm cells. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1310–1325. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-West PH, Robson L, Evans DJ. Craniofacial development: the tissue and molecular interactions that control development of the head. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2003;169:1–138. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55570-1. III–VI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel JP, Wainwright PC. A model system of structural duplication: Homologies of adductor mandibulae muscles in tetraodontiform fishes. Systematic Biology. 1997;46:441–463. [Google Scholar]

- Friel JP, Wainwright PC. Evolution of complexity in motor patterns and jaw musculature of tetraodontiform fishes. J Exp Biol. 1999;202(Pt 7):867–880. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.7.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser RF. Development of Facial Muscles in Man. American Journal of Anatomy. 1967;120 357-&. [Google Scholar]

- Gosline WA. Jaw Muscle Configuration in Some Higher Teleostean Fishes. Copeia. 1986:705–713. [Google Scholar]

- Grammatopoulos GA, Bell E, Toole L, Lumsden A, Tucker AS. Homeotic transformation of branchial arch identity after Hoxa2 overexpression. Development. 2000;127:5355–5365. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier J, Teillet MA, Grifone R, Kelly RG, Duprez D. Relationship between neural crest cells and cranial mesoderm during head muscle development. PLoS ONE. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004381. pe4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A. Mandibular arch musculature of anuran tadpoles, with comments on homologies of amphibian jaw muscles. J Morphol. 2001;247:1–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-4687(200101)247:1<1::AID-JMOR1000>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker A, Guthrie S. A distinct developmental programme for the cranial paraxial mesoderm in the chick embryo. Development. 1998;125:3461–3472. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall EK. Experimental modifications of muscle development in Amblystoma puncatum. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1950;113:355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. Journal of Morphology. 1951;88:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanken J, Klymkowsky MW, Alley KE, Jennings DH. Jaw muscle development as evidence for embryonic repatterning in direct-developing frogs. Proc Biol Sci. 1997;264:1349–1354. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta K, Schilling TF, BreMiller RA, Kimmel CB. Specification of jaw muscle identity in zebrafish: correlation with engrailed-homeoprotein expression. Science. 1990;250:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.1978412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens BA, Rodgers B, Mina M. Tissue-specific expression of Fgfr2b and Fgfr2c isoforms, Fgf10 and Fgf9 in the developing chick mandible. Arch Oral Biol. 2006;51:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrel A, Podos J, Huber SK, Hendry AP. Evolution of bite force in Darwin's finches: a key role for head width. J Evol Biol. 2005;18:669–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday CM, Witmer LM. Archosaur adductor chamber evolution: integration of musculoskeletal and topological criteria in jaw muscle homology. J Morphol. 2007;268:457–484. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jheon AH, Schneider RA. The cells that fill the bill: neural crest and the evolution of craniofacial development. J Dent Res. 2009;88:12–21. doi: 10.1177/0022034508327757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G. Muscle and tendon morphogenesis in the avian hind limb. Development. 1998;125:4019–4032. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.20.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardon G, Harfe BD, Tabin CJ. A Tcf4-positive mesodermal population provides a prepattern for vertebrate limb muscle patterning. Dev Cell. 2003;5:937–944. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RG, Jerome-Majewska LA, Papaioannou VE. The del22q11.2 candidate gene Tbx1 regulates branchiomeric myogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2829–2840. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymkowsky MW, Hanken J. Whole-mount staining of Xenopus and other vertebrates. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:419–441. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RD, Mebus K, Roehl HH. Mandibular arch muscle identity is regulated by a conserved molecular process during vertebrate development. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2008;310:355–369. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köntges G, Lumsden A. Rhombencephalic neural crest segmentation is preserved throughout craniofacial ontogeny. Development. 1996;122:3229–3242. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Liévre CS. Participation of neural crest-derived cells in the genesis of the skull in birds. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 1978;47:17–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:61–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.012103.135836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Yung RF, Lee HC, Chen WT, Chen YH, Tsai HJ. Myogenic regulatory factors Myf5 and Myod function distinctly during craniofacial myogenesis of zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2006;299:594–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Capsulin: a novel bHLH transcription factor expressed in epicardial progenitors and mesenchyme of visceral organs. Mech Dev. 1998;73:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JR, Bassel-Duby R, Hawkins A, Chang P, Valdez R, Wu H, Gan L, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Control of facial muscle development by MyoR and capsulin. Science. 2002;298:2378–2381. doi: 10.1126/science.1078273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lwigale RY, Schneider RA. Other Chimeras: Quail-duck and mouse-chick. In: Bronner-Fraser M, editor. Methods in Avian Embryology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 59–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClearn D, Noden DM. Ontogeny of architectural complexity in embryonic quail visceral arch muscles. Am J Anat. 1988;183:277–293. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001830402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997;387:83–90. doi: 10.1038/387083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lee SJ. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12457–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill AE, Eames BF, Weston SJ, Heath T, Schneider RA. Mesenchyme-dependent BMP signaling directs the timing of mandibular osteogenesis. Development. 2008;135:1223–1234. doi: 10.1242/dev.015933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KA, Barrow J, Collinson JM, Davidson S, Lear M, Hill RE, Mackenzie A. A highly conserved Wnt-dependent TCF4 binding site within the proximal enhancer of the anti-myogenic Msx1 gene supports expression within Pax3-expressing limb bud muscle precursor cells. Dev Biol. 2007;311:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mina M, Wang YH, Ivanisevic AM, Upholt WB, Rodgers B. Region- and stage-specific effects of FGFs and BMPs in chick mandibular morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2002;223:333–352. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Olson EN. Defining the regulatory networks for muscle development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:445–453. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DS, Quignon P, Bustamante CD, Sutter NB, Mellersh CS, Parker HG, Ostrander EA. A mutation in the myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison ND, Price BA, Conner DA, Keene DR, Olson EN, Tabin CJ, Schweitzer R. Regulation of tendon differentiation by scleraxis distinguishes force-transmitting tendons from muscle-anchoring tendons. Development. 2007;134:2697–2708. doi: 10.1242/dev.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae M, Sasaki K. Homologies of the adductor mandibulae muscles in Tetraodontiformes as indicated by nerve branching patterns. Ichthyological Research. 2004;51:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan E, Monovich A, Tirosh-Finkel L, Harrelson Z, Rousso T, Rinon A, Harel I, Evans SM, Tzahor E. The contribution of Islet1-expressing splanchnic mesoderm cells to distinct branchiomeric muscles reveals significant heterogeneity in head muscle development. Development. 2008;135:647–657. doi: 10.1242/dev.007989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. The control of avian cephalic neural crest cytodifferentiation. I. Skeletal and connective tissues. Developmental Biology. 1978;67:296–312. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. The embryonic origins of avian cephalic and cervical muscles and associated connective tissues. Am J Anat. 1983a;168:257–276. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001680302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. The role of the neural crest in patterning of avian cranial skeletal, connective, and muscle tissues. Dev Biol. 1983b;96:144–165. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. Patterning of avian craniofacial muscles. Dev Biol. 1986;116:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. Interactions and fates of avian craniofacial mesenchyme. Development. 1988;103:121–140. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Francis-West P. The differentiation and morphogenesis of craniofacial muscles. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1194–1218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Marcucio R, Borycki AG, Emerson CP., Jr Differentiation of avian craniofacial muscles: I. Patterns of early regulatory gene expression and myosin heavy chain synthesis. Dev Dyn. 1999;216:96–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199910)216:2<96::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Schneider RA. Neural crest cells and the community of plan for craniofacial development: historical debates and current perspectives. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;589:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Trainor PA. Relations and interactions between cranial mesoderm and neural crest populations. J Anat. 2005;207:575–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki JL, Burke AC. Hox genes and morphological identity: axial versus lateral patterning in the vertebrate mesoderm. Development. 2000;127:4265–4275. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson L, Falck P, Lopez K, Cobb J, Hanken J. Cranial neural crest cells contribute to connective tissue in cranial muscles in the anuran amphibian, Bombina orientalis. Dev Biol. 2001;237:354–367. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualetti M, Ori M, Nardi I, Rijli FM. Ectopic Hoxa2 induction after neural crest migration results in homeosis of jaw elements in Xenopus. Development. 2000;127:5367–5378. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell JK, Schreibman MP, Humason GL. Humason's animal tissue techniques. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pryce BA, Brent AE, Murchison ND, Tabin CJ, Schweitzer R. Generation of transgenic tendon reporters, ScxGFP and ScxAP, using regulatory elements of the scleraxis gene. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1677–1682. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayne J, Crawford GN. The development of the muscles of mastication in the rat. Ergeb Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1971;44:1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reduker DW. Functional analysis of the masticatory apparatus in two species of Myotis. Journal of Mammalogy. 1983;64:277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Rinon A, Lazar S, Marshall H, Buchmann-Moller S, Neufeld A, Elhanany-Tamir H, Taketo MM, Sommer L, Krumlauf R, Tzahor E. Cranial neural crest cells regulate head muscle patterning and differentiation during vertebrate embryogenesis. Development. 2007;134:3065–3075. doi: 10.1242/dev.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Guzman M, Montero JA, Santesteban E, Ganan Y, Macias D, Hurle JM. Tendon-muscle crosstalk controls muscle bellies morphogenesis, which is mediated by cell death and retinoic acid signaling. Dev Biol. 2007;302:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R. The MyoD family of transcription factors and skeletal myogenesis. Bioessays. 1995;17:203–209. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Schnegelsberg PN, Stead RH, Braun T, Arnold HH, Jaenisch R. MyoD or Myf-5 is required for the formation of skeletal muscle. Cell. 1993;75:1351–1359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90621-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K. Comparative functional morphology of mandibular forward movement during mastication of two murid rodents, Apodemus speciosus (Murinae) and Clethrionomys rufocanus (Arvicolinae) J Morphol. 1997;231:131–141. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199702)231:2<131::AID-JMOR2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Le Mentec C, Lepage M, Mazan S. Embryonic expression of Tbx1, a DiGeorge syndrome candidate gene, in the lamprey Lampetra fluviatilis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2002;2:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SA, Lauder GV. Historical Transformation of Functional Design - Evolutionary Morphology of Feeding Mechanisms in Loricarioid Catfishes. Systematic Zoology. 1986;35:489–508. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling TF, Kimmel CB. Musculoskeletal patterning in the pharyngeal segments of the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1997;124:2945–2960. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling TF, Walker C, Kimmel CB. The chinless mutation and neural crest cell interactions in zebrafish jaw development. Development. 1996;122:1417–1426. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RA. Neural crest can form cartilages normally derived from mesoderm during development of the avian head skeleton. Developmental Biology. 1999;208:441–455. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RA. Developmental mechanisms facilitating the evolution of bills and quills. J Anat. 2005;207:563–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RA. How to tweak a beak: molecular techniques for studying the evolution of size and shape in Darwin's finches and other birds. Bioessays. 2007;29:1–6. doi: 10.1002/bies.20517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RA, Helms JA. The cellular and molecular origins of beak morphology. Science. 2003;299:565–568. doi: 10.1126/science.1077827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F, Dickson BJ. Muscle building; mechanisms of myotube guidance and attachment site selection. Dev Cell. 2004;7:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Chyung JH, Murtaugh LC, Brent AE, Rosen V, Olson EN, Lassar A, Tabin CJ. Analysis of the tendon cell fate using Scleraxis, a specific marker for tendons and ligaments. Development. 2001;128:3855–3866. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetani Y, Sugahara F, Kawakami Y, Murakami Y, Hirano S, Kuratani S. Heterotopic shift of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in vertebrate jaw evolution. Science. 2002;296:1316–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1068310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih HP, Gross MK, Kioussi C. Cranial muscle defects of Pitx2 mutants result from specification defects in the first branchial arch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5907–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701122104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukunami C, Takimoto A, Oro M, Hiraki Y. Scleraxis positively regulates the expression of tenomodulin, a differentiation marker of tenocytes. Dev Biol. 2006;298:234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KK. The form of the feeding apparatus in terrestrial vertebrates: studies of adaptation and constraint. In: Hanken J, Hall BK, editors. The Skull: Functional and Evolutionary Mechanisms. Vol. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1993. pp. 150–196. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KK. Development of craniofacial musculature in Monodelphis domestica (Marsupialia, Didelphidae) J Morphol. 1994;222:149–173. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1052220204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KK, Schneider RA. Have Gene Knockouts Caused Evolutionary Reversals in the Mammalian First Arch? BioEssays. 1998;20:245–255. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199803)20:3<245::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TG, Sweetman D, Patterson M, Keyse SM, Munsterberg A. Feedback interactions between MKP3 and ERK MAP kinase control scleraxis expression and the specification of rib progenitors in the developing chick somite. Development. 2005;132:1305–1314. doi: 10.1242/dev.01699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni VC. The role of kinesis and mechanical advantage in the feeding apparatus of some partridges and quails. Annals of Zoology. 1979;15:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Stedman HH, Kozyak BW, Nelson A, Thesier DM, Su LT, Low DW, Bridges CR, Shrager JB, Minugh-Purvis N, Mitchell MA. Myosin gene mutation correlates with anatomical changes in the human lineage. Nature. 2004;428:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature02358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Buckingham M. The birth of muscle progenitor cells in the mouse: spatiotemporal considerations. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2000;48:225–268. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60758-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh-Finkel L, Elhanany H, Rinon A, Tzahor E. Mesoderm progenitor cells of common origin contribute to the head musculature and the cardiac outflow tract. Development. 2006;133:1943–1953. doi: 10.1242/dev.02365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokita M. Morphogenesis of parrot jaw muscles: understanding the development of an evolutionary novelty. J Morphol. 2004;259:69–81. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokita M, Kiyoshi T, Armstrong KN. Evolution of craniofacial novelty in parrots through developmental modularity and heterochrony. Evol Dev. 2007;9:590–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomo S, Tomo I, Townsend GC, Hirata K. Masticatory muscles of the great-gray kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2007;290:382–388. doi: 10.1002/ar.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor P, Krumlauf R. Plasticity in mouse neural crest cells reveals a new patterning role for cranial mesoderm. Nature Cell Biology. 2000;2:96–102. doi: 10.1038/35000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor PA, Sobieszczuk D, Wilkinson D, Krumlauf R. Signalling between the hindbrain and paraxial tissues dictates neural crest migration pathways. Development. 2002;129:433–442. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker AS, Lumsden A. Neural crest cells provide species-specific patterning information in the developing branchial skeleton. Evol Dev. 2004;6:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142x.2004.04004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turingan RG. Ecomorphological relationships among Caribbean tetraodontiform fishes. Journal of Zoology of London. 1994;233:493–521. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull WD. Mammalian masticatory apparatus. Fieldiana Geology. 1970;18:149–356. [Google Scholar]

- Tzahor E, Kempf H, Mootoosamy RC, Poon AC, Abzhanov A, Tabin CJ, Dietrich S, Lassar AB. Antagonists of Wnt and BMP signaling promote the formation of vertebrate head muscle. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3087–3099. doi: 10.1101/gad.1154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meij MA, Bout RG. Scaling of jaw muscle size and maximal bite force in finches. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:2745–2753. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Scheven G, Alvares LE, Mootoosamy RC, Dietrich S. Neural tube derived signals and Fgf8 act antagonistically to specify eye versus mandibular arch muscles. Development. 2006a;133:2731–2745. doi: 10.1242/dev.02426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Scheven G, Bothe I, Ahmed MU, Alvares LE, Dietrich S. Protein and genomic organisation of vertebrate MyoR and Capsulin genes and their expression during avian development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006b;6:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtler F, Jacob M. Origin and development of the cranial skeletal muscles. Bibl Anat. 1986:24–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke TA, Gubbels S, Schwartz J, Richman JM. Expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3) in the developing head and face. Dev Dyn. 1997;210:41–52. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199709)210:1<41::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow BB, Takimoto-Kimura R, Burke AC. Global patterning of the vertebrate mesoderm. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2371–2381. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AE. Grades and Clades among Rodents. Evolution. 1965;19:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ziermann JM, Olsson L. Patterns of spatial and temporal cranial muscle development in the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis (Anura : Pipidae) Journal of Morphology. 2007;268:791–804. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zusi RL. Patterns of diversity in the avian skull., The Skull, Volume 2: Patterns of Structural and Systematic Diversity. University of Chicago Press; 1993. pp. 391–437. [Google Scholar]

- Zweers GA. Structure, movement, and myography of the feeding apparatus of the mallard (Anas platyrhynochos L.): A study in functional anatomy. Neth. J. Zool. 1974:24. [Google Scholar]

- Zweers GA, Kunz G, Mos J. Functional anatomy of the feeding apparatus of the mallard (Anas platyrhynchos L.) structure, movement, electro-myography and electro-neurography (author's transl) Anat Anz. 1977;142:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]