Summary

The anterior midgut of the larval yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti generates a luminal pH in excess of 10 in vivo and similar values are attained by isolated and perfused anterior midgut segments after stimulation with submicromolar serotonin. In the present study we investigated the mechanisms of strong luminal alkalinization using the intracellular fluorescent indicator BCECF-AM. Following stimulation with serotonin, we observed that intracellular pH (pHi) of the anterior midgut increased from a mean of 6.89 to a mean of 7.62, whereas pHi of the posterior midgut did not change in response to serotonin. Moreover, a further increase of pHi to 8.58 occurred when the pH of the luminal perfusate was raised to an in vivo-like value of 10.0. Luminal Zn2+ (10 μmol l–1), an inhibitor of conductive proton pathways, did not inhibit the increase in pHi, the transepithelial voltage, or the capacity of the isolated tissue to alkalinize the lumen. Finally, the transapical voltage did not significantly respond to luminal pH changes induced either by perfusion with pH 10 or by stopping the luminal perfusion with unbuffered solution which results in spontaneous luminal alkalinization. Together, these results seem to rule out the involvement of conductive pathways for proton absorption across the apical membrane and suggest that a serotonin-induced alkaline pHi plays an important role in the generation of an alkaline lumen.

Keywords: BCECF, intracellular pH, membrane voltage, microelectrodes, transepithelial voltage, serotonin, zinc

INTRODUCTION

The anterior midgut (anterior stomach) of the larval mosquito is responsible for generating a luminal pH (pHL) that may be greater than 10, as first demonstrated in intact animals by colorimetric methods using ingested pH indicator (Dadd, 1975) and later confirmed by H+-sensitive microelectrode studies (Onken et al., 2008). The mechanisms of base secretion and/or acid absorption involved have been studied with intact larvae, with semi-intact preparations (Boudko et al., 2001a; Boudko et al., 2001b) and with fully isolated, perfused gut segments (Onken et al., 2008). Immunohistochemical observations (Zhuang et al., 1999) as well as the results of studies with intact and semi-intact larvae have led to the general hypothesis that alkali secretion is energized by a basolateral V-type proton ATPase (Boudko et al., 2001b), in combination with an apical Cl–/HCO3– exchanger (Boudko et al., 2001a). A challenge for the second part of the hypothesis is presented by the fact that direct HCO3– secretion alone can generate only a moderately alkaline pH of about 8.5. Therefore, attaining pHL values >10 as reported for the larval mosquito midgut would be impossible by a simple exchange of Cl– for HCO3–. Consequently, it was hypothesized that achieving these high pHL values would require a secondary uptake of H+ from the lumen following HCO3– secretion. Another alternative that is as yet unexplored is the possibility that direct secretion of CO32– per se could also accomplish a high pHL. However, this possibility has always been considered unlikely because of the very low amounts of CO32– present at normal intracellular pH (pHi) values

In isolated and perfused midgut preparations, the transepithelial potential (Vte) declines to a small, usually lumen-negative value within minutes of the onset of perfusion with control saline (Clark et al., 1999; Clark et al., 2000). Luminal alkalinization under these conditions is very slow and hardly detectable (Onken et al., 2008). Application of submicromolar serotonin causes a sustained increase in the Vte to values of the order of 10–40 mV lumen negative. This response is maximal in about 20 min and is accompanied by a significant stimulation of luminal alkalinization, as measured in stop-flow experiments using pH indicator dye or H+-selective microelectrodes (Onken et al., 2008). Both the electrical and chemical responses are reversible on washout of serotonin. It is probable that serotonin is the major natural endogenous excitatory stimulus for epithelial transport and motility in the midgut, and the gut indeed receives a rich serotonergic innervation (Moffett and Moffett, 2005). On the other hand, roles for other substances, either as intermediaries or modulators, are also likely as the gut also has a substantial population of enteroendocrine cells, and modulatory effects of some neuropeptides have been reported (Onken et al., 2004).

The present studies were performed to determine the consequences of stimulation of alkali secretion on the pHi and to evaluate the possibility of passive, conductive uptake of H+ across the apical membrane as part of this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

For the optical experiments, eggs of Aedes aegypti were obtained from Dr Carl Lowenberger (Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada) and reared in covered plastic dishes in a temperature-controlled chamber at 27°C. The water was a 50:50 mixture of deionized water and City of Edmonton (Alberta, Canada) tap water. Larvae were fed daily with ground Tetramin (Tetrawerke, Melle, Germany). For non-optical experiments, eggs of the Vero Beach strain were provided by Dr Marc Klowden (University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA) and reared under similar conditions. Larvae that were in day 1 or day 2 of the 4th instar were chosen for experiments. Isolation, mounting and perfusion of larval midguts were accomplished using previously described techniques (Onken et al., 2004; Onken et al., 2008) and resulted in removal of the peritrophic membrane from the preparation.

Solutions and drugs

The hemolymph side of the tissue was gravity superfused (0.5 ml min–1) with oxygenated saline with a composition based on larval Aedes hemolymph (Edwards, 1982a; Edwards, 1982b); in mmol l–1: NaCl, 42.5; KCl, 3.0; MgCl2, 0.6; CaCl2, 5.0; NaHCO3, 5.0; succinic acid, 5.0; malic acid, 5.0; l-proline, 5.0; l-glutamine, 9.1; l-histidine, 8.7; l-arginine, 3.3; dextrose, 10.0; Hepes, 25. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH. The gut lumen was perfused with NaCl (100 mmol l–1) at a rate of 50–150 μlh–1, using one or more Aladdin syringe pumps (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). The components of the above solutions were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA), Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or Mallinckrodt (Hazelwood, MO, USA). Serotonin (Sigma) and ZnCl2 (Baker Chemical, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) were directly dissolved in the saline.

Fluorescence microscopy for measurement of pHi

pHi measurements were obtained following the protocol described previously (Parks et al., 2007). Briefly, the perfusion chamber was mounted on the stage of a Nikon Eclipse TM-300 inverted microscope and midguts were subjected to differential interference contrast microscopy for initial focusing and for photographic records of the appearance of the mounted tissue. The microscope was illuminated with a xenon arc lamp (Lambda LS; Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and a TM-FM epifluorescence attachment was used for fluorescence imaging. The BCECF trapped in the tissue (see below) was excited at its absorption peak of 495 nm; 440 nm was used as an isobestic wavelength. At 10 s intervals, images at these wavelengths were captured digitally on a mono 12-bit charge-coupled device camera (Retiga EXi, Burnaby, BC, Canada). Northern Eclipse version 6 software (Mississauga, ON, Canada) was used to compile the 495 to 440 nm ratios as an indication of the pHi.

After the tissue was attached to the perfusion pipette, it was loaded with the pH-sensitive intracellular dye BCECF-AM (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as follows: 2 μl of a 5 mmol l–1 solution of BCECF-AM dissolved in DMSO containing 20% pluronic acid was added to the chamber volume of 450 μl of standard saline to achieve a final BCECF-AM concentration of 0.5 μmol l–1. After 30 min of incubation in the dye solution, perfusion and superfusion were started, washing away all dye not taken up by the tissue. In three control experiments, 30 min exposure to the BCECF-DMSO-pluronic acid mixture with which the tissue was dye-loaded was found to have no measurable effect on the transepithelial potential of unstimulated tissues, nor did it affect the electrical response to serotonin or the ability of tissues to secrete alkali in response to serotonin.

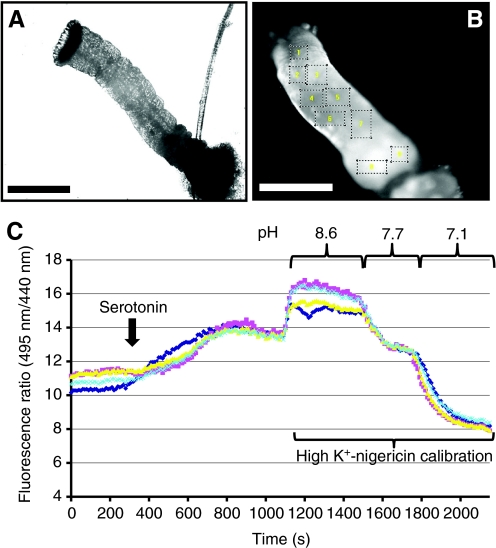

At the beginning of each experiment, three to eight areas of interest were established on the CCD image of the gut. Fig. 1 shows an example of such areas in a typical experiment. Data presented represent the average of fluorescence collected from these areas, each of which is estimated to correspond to approximately three to seven of the large differentiated epithelial cells together with perhaps twice this number of the much smaller regenerative and epithelioendocrine cells.

Fig. 1.

Experimental set-up for intracellular pH (pHi) monitoring of regions in the midgut of larval (4th instar) Aedes aegypti. (A) DIC image of the midgut preparation as observed on the experimental apparatus (scale bar 200 μm). (B) Corresponding fluorescence image (F495) of the same midgut from A following loading of the pH-sensitive dye BCECF-AM. Dotted boxes represent regions of interest that were used to observe ratiometric fluorescence changes (scale bar, 200 μm). (C) Representative traces of four regions of interest in the midgut and their corresponding fluorescence ratios (F495/F440) generated from excitation of cells loaded with BCECF-AM. This graph demonstrates the ability to convert observed changes in fluorescence ratios to pHi values by using the high K+-nigericin calibration for each individual cell.

At the end of each experiment, fluorescence ratios recorded during the experiment were calibrated by superfusing the tissue successively with high-K+ solutions (in mmol l–1: 75 potassium gluconate, 20 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 20 Hepes) containing 5 μmol l–1 nigericin, adjusted to cover the range of pH values 6.6–8.4 (see Fig. 1). The values obtained at each calibration set point were then used to generate a regression equation for each of the designated areas of interest. This equation was then applied to the ratiometric data obtained over the course of the whole experiment, resulting in an internally calibrated pHi trace that represents an average value for the several cells within that area. In several initial studies, the ×40 objective of the microscope was used and individual cells were outlined as areas of interest. These studies failed to indicate heterogeneity among the large principal cells in either initial pHi or response to serotonin.

Measurements of Vte, cellular membrane potentials and luminal alkalinization

In the optical experiments it was not practical to make simultaneous measurements of tissue electrical parameters. Therefore, parallel experiments were conducted to determine the effects of Zn2+ on Vte and luminal alkalinization, and to measure changes in transbasal potential (Vbl) and transapical potential (Vapi) during luminal alkalinization. Mounting and perfusion of isolated anterior midguts, the measurement of Vte and luminal alkalinization, and the measurement of membrane voltages were conducted as described in detail previously (Clark et al., 2000; Onken et al., 2008). Briefly, for these experiments the luminal perfusate contained m-Cresol Purple (0.04% w/v) for evaluation of luminal alkalinization. Luminal perfusion was interrupted and a color change from orange to purple (pK2=8.32) [see Fig. 1 of Onken et al. (Onken et al., 2008)] was taken to indicate luminal alkalinization. These evaluations were observed using a dissecting microscope and recorded using a digital camera (Power-Shot S40, Canon USA, Lake Success, NY, USA). Vte was measured with a voltage clamp (VCC 600, Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) and calomel electrodes connected to the bath and perfusate with agar bridges (3% agar in 3 mol l–1 KCl). For the measurement of membrane potentials glass microelectrodes were pulled (model 700B, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA) from 1.5 mm o.d. microfilament capillaries (Omega-Dot 30-32-1, Frederick Haer, Brunswick, ME, USA) to tip resistances of 30–50 MΩ and filled with 3 μmol l–1 KCl. Microelectrodes were advanced under visual control using a hydraulic drive (Mechanical Developments, South Gate, CA, USA) for the final approach to the cells. Vbl values were measured using an electrometer (A-M Systems model 1600, Carlsborg, WA, USA). From Vte and Vbl the corresponding Vapi values were calculated. Data were digitized using a Labtrax 4 AD converter and analyzed using Data-Trax software (World Precision Instruments).

Analysis and statistics

Data from the optical experiments were transferred to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, where fluorescence ratios were converted to pHi values by reference to linear fits of the corresponding calibration points. pHi (or ΔpHi) for the different regions of interest was then pooled (averaged) for each isolated midgut preparation. In Results, the means ± s.e.m. of the independent preparations are given. Indicated N values refer to the number of different preparations used. Differences between groups were tested with the pooled results from different preparations. Student's paired t-test was used when comparing results obtained with each of the individual tissues, whereas Student's unpaired t-test was used when results from different groups of preparations were compared. Significance was assumed at P<0.05.

For the non-optical experiments, voltage values were extracted from the digitized voltage traces and transferred to a spreadsheet for statistical analysis. The results of multiple impalements on one isolated midgut were pooled before further analysis. Results are presented as means ± s.e.m. Indicated N values refer to the number of independent experiments with different preparations. Differences between groups were tested with Student's paired t-test, using the pooled data from different midgut preparations. Significance was assumed at P<0.05.

RESULTS

pHi of anterior and posterior midgut cells under baseline conditions, and the effect of serotonin

In these experiments, the hemolymph side of the tissue was superfused with standard mosquito saline while the lumen was perfused with unbuffered 100 mmol l–1 NaCl adjusted to pH 7.0. In 71 regions of 10 anterior stomach preparations the average pHi was found to be 6.89±0.15 (N=10), whereas the average pHi was 6.87±0.28 (N=4) in 19 regions of four posterior stomach preparations.

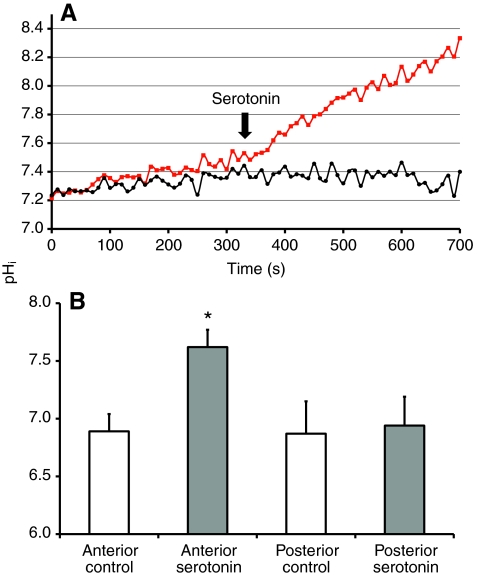

Addition of serotonin (0.2 μmol l–1) led to a sustained increase in pHi in the anterior midgut, from the control mean of 6.89±0.15 to 7.62±0.15 (N=10; P<0.05). A representative time course of pHi after serotonin is shown in Fig. 2. In many cases, pHi values exceeded 8 – the maximal value recorded was 8.66. The time course of the pHi rise was similar to that of the Vte response recorded in previous studies (Clark et al., 1999). In contrast, in the four experiments in which measurements were made simultaneously from the posterior midgut, either no significant changes or modest acidifications of pHi were observed (see Fig. 2A,B). In the posterior regions pHi before and after addition of serotonin was 6.87±0.28 and 6.94±0.25 (N=4; P>0.05).

Fig. 2.

Effects of serotonin on the pHi in isolated and perfused anterior or posterior midguts. (A) pHi time courses of representative areas of interest from the anterior (red) and posterior (black) midgut of larval (4th instar) Aedes aegypti, showing the influence of addition of 0.2 μmol l–1 of serotonin (arrow) to the hemolymph-side bath. Hemolymph-side bath: oxygenated mosquito saline (pH 7). Luminal perfusate: NaCl (100 mmol l–1, pH 7). (B) Average pHi values for anterior (N=71 areas of interest from 10 different tissues) and posterior (N=19 areas of interest from four different tissues) midguts before and after addition of serotonin. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference from control (P<0.05).

pHi response to pHL 10.0 in the presence and absence of luminal Zn2+

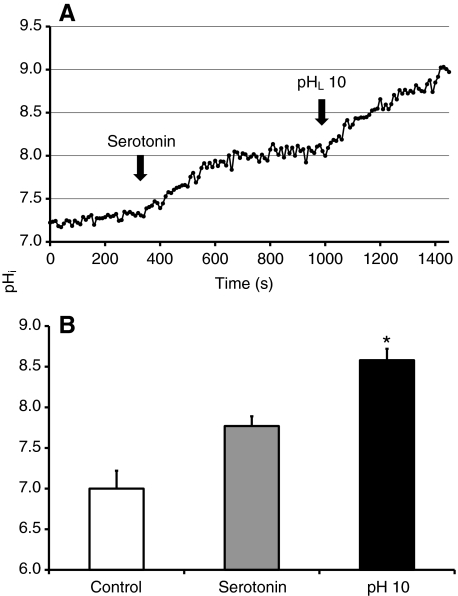

In these experiments, the lumen was initially perfused with 100 mmol l–1 NaCl buffered to pH 7.0. After the stability of the preparation was established, serotonin was added to the bath. Following the maximal effect of serotonin, the luminal perfusate was changed to pH 10.0 (buffered with 10 mmol l–1 Tris; `alkaline luminal perfusate') which would be more typical of physiological conditions in an in vivo stimulated gut. A typical experiment is shown in Fig. 3A. For 41 areas from four tissues the mean pHi with serotonin was 7.77±0.12 (N=4) and significantly rose to 8.58±0.14 (N=4) with alkaline luminal perfusate (P<0.05; see Fig. 3B). The highest value recorded was 10.04. It is important to mention here that the pH dependence of the fluorescence excitation spectrum of BCECF-AM becomes non-linear above a pH of 8.6. Therefore, results above a pH value of 8.6 should be interpreted with caution as accurate calibrations are not possible. We can only interpret these results as being above a pH of 8.6. Unfortunately, there are no dyes available for accurate ratiometric pH imaging in the high pH range.

Fig. 3.

Influence of luminal pH (pHL) 10 on pHi in the anterior midgut. (A) pHi time course of a representative area of interest from the anterior midgut of larval (4th instar) Aedes aegypti, showing the influence of hemolymph-side addition of serotonin (0.2 μmol l–1) in the presence of hemolymph-side mosquito saline (pH 7) and luminal NaCl (100 mmol l–1, pH 7), and the effect of an increase of the pHL to 10. (B) Average pHi for anterior midguts (N=41 areas of interest of four different tissues) under control conditions, after hemolymph-side addition of serotonin, and after switching to a luminal perfusate of pH 10. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference from control plus serotonin (P<0.05).

To test the potential involvement of inward-directed H+ conductive channels in the alkalinization of the lumen we performed three additional experiments where the luminal perfusate was pH 10 and 22 total areas of interest were monitored. ZnCl2 (10 μmol l–1) was included in the alkaline luminal perfusate as a blocker of H+ channels (DeCoursey, 2003). In these experiments, the mean control value with serotonin was 7.11±0.19 (N=3) and after a change to alkaline (pH 10) luminal perfusate in the presence of Zn2+, the mean pHi attained was 8.18±0.19 (N=3). The change in pHi in response to alkaline luminal perfusate in the presence of Zn2+ was not significantly different from that recorded in the absence of Zn2+ (P>0.05). Furthermore, the rate of increase of pHi after changing to alkaline luminal perfusate was also not affected (P>0.05) by the presence of Zn2+ (see Fig. 4A).

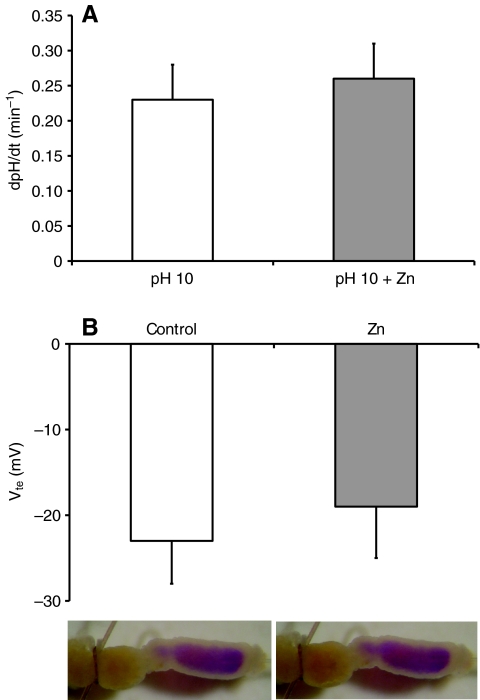

Fig. 4.

Effects of luminal Zn2+ on pHi at pHL 10, on the transepithelial voltage (Vte), and on luminal alkalinization. (A) Effect of luminal ZnCl2 (10 μmol l–1) on the rate of pHi alkalinization after switching to pHL 10 in the presence of serotonin (means + s.e.m.). Control: 41 areas of interest from four different tissues. In the presence of Zn2+: 22 areas of interest from three different tissues. (B) Average lumen-negative transepithelial voltage (Vte, means – s.e.m.) of five isolated and perfused anterior midgut preparations of larval (4th instar) Aedes aegypti in the presence and absence of ZnCl2 (10 μmol l–1), and photographs of a representative preparation of the anterior midgut of larval 4th instar Aedes aegypti at identical times after perfusion stop in the presence (right) and absence (left) of ZnCl2 (10 μmol l–1).

In parallel experiments, we measured Vte at a pHL of 7 and compared the capability of the preparations for luminal alkalinization using m-Cresol Purple in the absence and presence of luminal Zn2+. No significant effect of luminal Zn2+ on Vte (P>0.05) was detected and no difference in the capacity for luminal alkalinization was observed. Fig. 4B shows a typical m-Cresol Purple response and the mean Vte values in the presence and absence of Zn2+ for five experiments.

Effects of alkaline luminal perfusate and spontaneous luminal alkalinization on tissue electrical parameters

In a first series of experiments, cells of serotonin-stimulated tissues were penetrated as described in Materials and methods, and after an acceptable penetration was achieved, the luminal perfusate was changed from pH 7.0 to pH 10.0. For 10 penetrations from five tissues the mean voltages at a pHL of 7 were Vte=–8±3 mV (N=5; lumen negative), Vbl=–87±5 mV (N=5; cell negative) and Vapi=–79±6 mV (N=5; cell negative). After the change to alkaline luminal perfusate the average voltages were Vte=–7±3 mV (N=5; lumen negative), Vbl=–94±6 mV (N=5; cell negative) and Vapi=–87±6 mV (N=5; cell negative). The means of Vte, Vbl and Vapi before and after switching to pH 10 in the luminal perfusion are not significantly different (P>0.05).

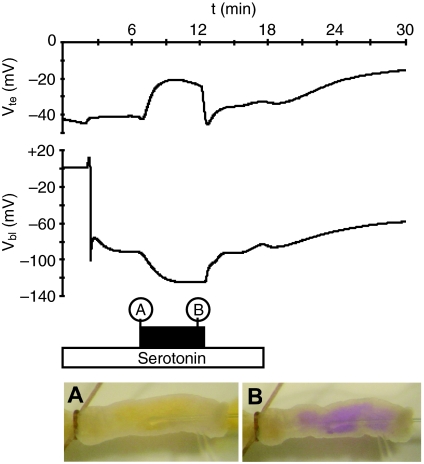

In a second series of experiments, the luminal perfusate was unbuffered 100 mmol l–1 NaCl and perfusion was interrupted after an acceptable penetration was achieved, allowing measurement of possible electrical changes accompanying spontaneous luminal alkalinization (observed by the color change of luminal m-Cresol Purple). The results were similar to those reported for the alkaline luminal perfusion experiments above. For 12 penetrations from five tissues, the mean control values were Vte=–22±6 mV (N=5; lumen negative), Vbl=–94±9 mV (N=5; cell negative) and Vapi=–72±10 mV (N=5; cell negative). The stable values recorded after perfusion stop were Vte=–19±4 mV (N=5; lumen negative), Vbl=–108±8 mV (N=5; cell negative) and Vapi=–89±7 mV (N=5; cell negative). A typical experiment is shown in Fig. 5. As for switching to pH 10 (see above), the means of Vte, Vbl and Vapi before and after luminal alkalinization by perfusion stop are not significantly different (P>0.05).

Fig. 5.

Selected experiment with an isolated and perfused anterior midgut of larval (4th instar) Aedes aegypti showing the maximal changes of membrane voltages observed during spontaneous luminal alkalinization after luminal perfusion stop. After stabilization of Vte at –40 mV (lumen negative), an epithelial cell in the anterior portion of the preparation was impaled with a microelectrode (see lower right in photographs A and B). Transbasal potential (Vbl) stabilized at –90 mV (cell negative). From these values the transapical voltage (Vapi) can be calculated to –50 mV (cell negative). Five minutes after successful impalement a photograph of the preparation was taken (A, showing yellow perfusate of neutral pH) and the perfusion pump was stopped as indicated by the black bar. Within 3 min Vte dropped to –20 mV, whereas Vbl hyperpolarized to over –120 mV (Vapi calculates under these conditions to –103 mV), and the m-Cresol Purple indicated an alkaline midgut lumen (photo B). Restarting the luminal perfusion resulted in a return of the voltages to their original values. Subsequent washout of hemolymph-side serotonin reduced the lumen-negative Vte to –15 mV and the membrane voltages Vbl and Vapi decreased to –57 mV and –42 mV, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Methodological aspects

The magnitude of the apparent change in pHi generated in the serotonin response appears to violate the principle of homeostasis of the intracellular milieu, and a careful consideration of its veracity is in order. In principle, the fluorescence changes reported here could arise as an artifact, in the absence of an actual general cytoplasmic pH change, in two ways. First, the BCECF indicator dye might have become concentrated in an intracellular sub-compartment which then became extremely alkaline as an effect of serotonin, or second, the dye might be secreted or simply leak out of the cells, and accumulate in an extracellular region that became alkaline as a result of the effect of serotonin. However, neither of these possibilities seems tenable. In either case, the dye compartment giving rise to the artifact would have to represent a significant fraction of the total dye contributing to the optical signal. In our preliminary studies conducted at high magnification, no brightly fluorescing intracellular entities were noted in the dye-loaded tissue, although some individual cells appeared to load dye more readily than others. Additionally, the intercellular spaces were not seen to fluoresce brightly in comparison with the cellular interiors, suggesting that alkaline compartments in the cell would not contribute to the observed alkalinization of pHi. In the second case, accumulation of the dye in the luminal solution would presumably not be a source of optical signal, especially during continuous luminal perfusion. Moreover, experiments where we stopped and restarted perfusion were never accompanied by a change in fluorescence intensity, suggesting that, if dye were transported to the gut lumen, it did not result in any significant signal relative to the cytoplasmic pool of BCECF. The epithelial cells in the anterior midgut do not have a brush border. Only relatively sparse and short microvilli were observed (Clark et al., 2005). Consequently, entrapment of dye in an extracellular space formed by a thick brush border can be excluded.

Another significant aspect that requires consideration is that BCECF fluorescence approaches maximum intensity at pH values above pH 8.6 and extremely alkaline pHi values should be interpreted with caution. In our experiments, this resulted in a very cautious interpretation of pHi in the cytoplasm of serotonin-stimulated cells, especially during high luminal pH perfusion. The development of pH-sensitive indicators with an alkaline pK is necessary for accurate assessment of pHi in this unique tissue.

Extremely alkaline pHi in larval mosquito midgut cells

In the absence of serotonin the pHi of anterior and posterior midgut cells is neutral to slightly acidic, as has been observed in many other tissues. In the anterior midgut, addition of serotonin results in a significant alkalinization of the intracellular medium, whereas the posterior midgut cells do not respond to serotonin with a pHi change (see Fig. 2A,B). Consequently, the increase of pHi seems to be a specific response of the cells responsible for luminal alkalinization. Under more in vivo-like conditions, namely in the presence of an alkaline lumen, the pHi was observed to be between 8 and 9. To our knowledge pHi values of this magnitude have never been observed before. At first sight this seems surprising given the dogma of the necessity for pHi to be highly regulated for proper metabolic function. However, this epithelial tissue is unique in that it is responsible for generating an extremely alkaline secretion and an alkaline intracellular medium is likely to be of mechanistic importance. If the cells have a conventional pHi of about 7, the whole transepithelial pH gradient of over 3 orders of magnitude would be carried by only the apical membrane that faces the extremely alkaline midgut lumen. By generating (and tolerating) a very alkaline intracellular medium the transepithelial pH gradient is separated into two smaller steps at the basolateral and apical membranes. Knowing that basolateral V-type H+-ATPases are activated by serotonin and are a necessary component of luminal alkalinization (Onken et al., 2008), we can assume that activation of the basolateral V-ATPases is responsible for generating the pH gradient across the basolateral membrane.

Proton-motive forces across the basolateral and apical membranes

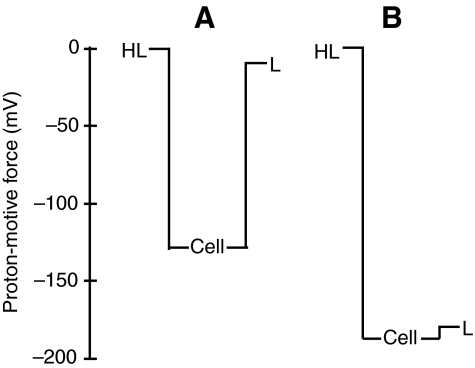

From our measurements of pHi and transmembrane voltages we can calculate the independent proton-motive forces for the basolateral and apical membranes in the presence of serotonin for two different conditions: (i) at a pHL of 7, and (ii) at a more in vivo-like pHL of 10 (see Fig. 6). At a neutral pH on both sides of the epithelium, proton-motive forces of above 100 mV dominate both membranes, favoring passive H+ movements from the extracellular solutions into the cell. In the presence of an alkaline lumen, the transbasal proton-motive force is huge, almost 190 mV, whereas the proton-motive force of the apical membrane is very small. The reversal potential of the V-ATPase, as estimated in various insect systems, is of the order of 120–180 mV (Beyenbach et al., 2000; Moffett, 1980; Moffett and Koch, 1988; Pannabecker et al., 1992). Thus, the proton-motive force across the basolateral membrane can be explained on the basis of H+ pumping by V-ATPases in this membrane. Of course, it is informative to analyze how the tissue can move from one state to the other, generating an alkaline pHL. A controlled opening of a conductive pathway for H+ in the apical membrane could make use of the transapical proton-motive force at neutral pH for transapical H+ absorption until H+ is in equilibrium at a very alkaline midgut lumen. Whilst the present study addressed the conductive pathway in the apical membrane (see below), one question that needs to be addressed in future studies is what determines the transapical voltage under control conditions that is responsible for the high driving force for H+ at neutral pH in the lumen.

Fig. 6.

Transepithelial profiles of the proton-motive force (in mV) calculated from the average membrane voltages and transmembrane pH gradients (A) for a control condition with mosquito saline containing serotonin as the hemolymph-side bath (pH 7) and luminal perfusion with NaCl (100 mmol l–1, pH 7), and (B) after increasing the pH of the luminal perfusate to 10. HL, hemolyph; L, lumen.

Implications of the results for the mechanism of strong midgut alkalinization

It seems to be well established that basolateral V-ATPase is driving transbasal H+ absorption and the overall transepithelial acid/base transport. Boudko and colleagues (Boudko et al., 2001a) analyzed anionic pathways in the apical membrane and proposed that apical Cl–/HCO3– exchange acts to alkalinize the anterior midgut lumen. However, in the isolated tissue, neither DIDS nor Cl–-free salines affected the capacity of the tissue for strong luminal alkalinization (Onken et al., 2008). Based on immunohistochemical observations, Okech and colleagues (Okech et al., 2008) proposed the presence of acid absorption via electrogenic cation/2H+ exchangers in the apical membrane. Indeed, the present studies show that there would be a driving force of approximately 100 mV, which is sufficient for a 2H+/Na+ exchanger (see below). However, in previous experiments (Onken et al., 2008) luminal amiloride did not inhibit luminal alkalinization. Of course, if the transporter mediated K+/2H+ exchange, the driving forces would be favorable for both ions. However, in the same study, Onken and colleagues found that an increased luminal K+ concentration, reducing the driving force for the exchange, also did not impair luminal alkalinization. Therefore, in the present study we addressed the possibility of transapical absorption of H+ through H+ channels. The theory is that the cell would excrete HCO3– followed by dissociation in the lumen and apical resorbtion via an apical H+ channel. However, micromolar Zn2+, used at concentrations known to block different H+ conductances (see DeCoursey, 2003) did not significantly affect the pHi change or the transepithelial voltage (see Fig. 4A,B). Moreover, the presence of luminal Zn2+ did not prevent luminal alkalinization (see Fig. 4B). We recognize that negative results in pharmacological approaches are not necessarily conclusive. However, it could be expected that in the presence of H+ channels a membrane would respond with significant voltage changes to alterations of the transmembrane pH gradient. As we did not observe such changes in our microelectrode experiments (see Results and Fig. 5), this suggests that apical H+ channels have no importance for H+ absorption and strong alkalinization in this tissue.

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is apparently not present in the cells of the anterior midgut of Aedes aegypti (Corena et al., 2002) and inhibitors of this enzyme were not effective at impeding luminal alkalinization in vitro (Onken et al., 2008). After finding the considerably alkaline pHi, the absence of cellular CA is less surprising, because high pH values should accelerate the hydration of CO2 and the dissociation of carbonic acid, reducing the usefulness of cellular CA. Smith and colleagues (Smith et al., 2007) have observed extracellular CA in the ectoperitrophic space of larval malaria mosquitoes (Anopheles gambiae), and this suggests that extracellular conversion of CO2 to HCO3–/CO32– and absorption of protons is involved in luminal alkalinization in this species. However, an extracellular CA has not been found in Aedes aegypti, and in our hands the addition of inhibitors of CA to the holding water did not prevent the living larvae from alkalinizing their anterior midguts (U. Jagadeshwaran and D.F.M., unpublished observation). If secretion of either HCO3– or CO32– turns out to be an important component of luminal alkalinization, the source of this HCO3–/CO32– must be addressed in future studies. Instead of respiratory CO2 from carbohydrate or lipid catabolism, HCO3– from amino acid catabolism is also a candidate that must be addressed in the absence of measurable CA activity (see Fry and Karet, 2007). The latter hypothesis is especially attractive, because amino acid catabolism also produces ammonia, which has been found at high concentrations in the mosquito hemolymph (Edwards, 1982b).

Implications of the results for future studies

In a previous study of strong alkalinization in isolated and perfused midgut preparations (Onken et al., 2008) we could not find experimental support for the anionic (DIDS-sensitive Cl–/HCO3– exchange) or cationic (amiloride-sensitive cation/H+ exchange) pathways in the apical membrane that had been proposed on the basis of results obtained with intact or semi-intact larvae (Boudko et al., 2001a; Okech et al., 2008). Future studies with isolated tissues should consider that both pathways may be present but equally potent in terms of generating strong luminal alkalinization. Thus, experiments that impede both mechanisms at the same time should be conducted.

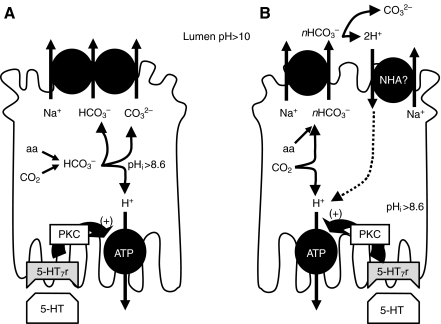

The results presented herein suggested that perhaps a novel mechanism for alkalinization of the lumen is present in this tissue. In Fig. 7 we show two possible models for net alkali secretion that could be present in the anterior midgut of the larval mosquito. Our results cannot differentiate between these two possibilities and we will discuss each of these potential models separately.

Fig. 7.

Potential modes of transport in the anterior midgut of the mosquito Aedes aegypti to achieve luminal alkalinization. (A) Alkalinization of the lumen is achieved via an apical Na+/CO32– co-transporter of unknown stoichiometry. This process is initiated by 5-HT stimulation of basolateral H+-ATPase pumping and an unusually high pHi. CO32– is proposed to be derived from either amino acid (aa) catabolism or CO2 hydration and subsequent H+ removal. (B) In this model, luminal alkalinization is achieved by the coordinated action of an apical electrogenic Na+/HCO3– co-transporter of unknown stoichiometry (n) and an apical electrogenic Na+/H+ antiporter (NHA). Upon secretion into the lumen, HCO3– is converted to CO32– and H+ and the H+ is re-absorbed into the cell via a NHA and then pumped across the basolateral membrane by the action of a basolateral H+ ATPase. The other components of the model are the same as described for part A of this figure. PKC, protein kinase C; 5-HT7r, 5-HT7 receptor.

In the first model, the main novel aspect is the proposal for direct CO32– secretion either via an apical Na+/CO32– co-transporter (NBC) or via a novel Na+/HCO3–/CO32– co-transporter (NBCC) operating in export mode. To our knowledge, there are no other reports of an NBC functioning in this particular mode (NBCC) simply because of the relative paucity of intracellular CO32– present in the cells. We have only represented NBCC in the proposed model for clarity (Fig. 7A). It is extremely important to consider that fundamental thermodynamic principles support the possibility that our models can operate in the stimulated tissues (Parks et al., 2008). It would be highly advantageous for the tissue to directly secrete CO32– as this would negate the requirement for potentially deleterious H+ import mechanisms. The following equation describes the equilibrium point for the net driving forces for a novel electrogenic NBCC as a function of the intracellular and extracellular concentrations CO32–, HCO3– and Na+:

|

(1) |

where μm is net driving force, Vm is membrane potential, R is the universal gas constant, T is temperature and F is Faraday's constant. We know the measured total CO2 in the lumen under stimulated conditions to be 58 mmol l–1 and the measured intracellular total CO2 to be ∼50 mmol l–1 (Boudko et al., 2001a). As we know the pK of the reaction HCO3–→CO32–+H+ is 10.3, we can therefore set the pH of the luminal solution at pH 10.3 and assume the composition of the luminal fluid to be in equilibrium at 29 mmol l–1 CO32– and 29 mmol l–1 HCO3–. A reasonable estimate for [Na+]i is 10 mmol l–1 and the luminal [Na+] in our perfusate is 100 mmol l–1. Additionally, we have measured the Vapi to be approximately –90 mV. Rearranging the above equation and solving for the intracellular carbonate levels required to drive the transport yields the following equation:

|

(2) |

At a resting pHi of 7.0 (measured in this experiment) and a measured total [CO2]i of 50.1 mmol l–1 (Boudko et al., 2001a), we can calculate the relative amounts of CO32– present using the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation. There would only be nominal amounts (∼25 μmol l–1) of carbonate (CO32–) present inside the cells at the resting pHi. These concentrations would be completely insufficient to allow uphill transport of CO32– into the solution present in the lumen. In fact, it would require an apical membrane potential of approximately –204 mV to drive this transport. However, at a pHi of 8.6, the estimated [CO32–]i would be ∼1 mmol l–1; at pHi8.8, it would be 1.6 mmol l–1; while for pHi9, the estimated [CO32–]i would be ∼2.5 mmol l–1. It is important to note that [CO32–]i relative to overall measured total [CO2] will rise steeply as pHi rises closer to its pK of 10.3.

Substituting the measured concentrations of ions into the equation above will yield the required [CO32–]i at the known membrane potential (–90 mV) to allow transport of CO32– out of the cell. At the measured value of –90 mV, a [CO32–]i of 2.03 mmol l–1 would be required to drive transport out via a putative NBCC. This value could be achieved at a pHi of 8.9, which is approximately within the range of pHi in our experiments given the significant limitations placed on us by the dye (see above). At a slightly more hyperpolarized Vapi of –100 mV, the required [CO32–]i would fall to 1.45 mmol l–1, or the value reached at pHi 8.77. Clearly, at these higher pHi values as measured, the [CO32–]i should become sufficient for direct CO32– transport via a NBCC. Moreover, this clearly illuminates the need for an elevation of pHi to aid in luminal alkalinization.

In the second model of secretion (see Fig. 7B), we suggest that the bulk of the base could be secreted as HCO3– via an apical Na+/HCO3– co-transporter (NBC) working in export mode followed by net acid absorption via a cation/H+ exchanger (see Fig. 7B). Such a mechanism has been proposed by Okech and colleagues (Okech et al., 2008) for the mosquito midgut; this was first envisaged (Dow, 1984) for the midgut of lepidopteran insect larvae, which achieve similarly alkaline pHL values.

Direct evidence for an electrogenic Na+/H+ antiporter (NHA) is lacking in our studies; furthermore, a NHA localized in the anterior midgut of Anopheles gambiae apparently is not expressed in the plasma membrane (Rheault et al., 2007). We performed a thermodynamic analysis to determine whether in fact it could function under the conditions found in the anterior midgut and whether the noted intracellular alkalinization would favor the operation of this combined mechanism. The following equation describes the equilibrium point for the net driving forces for an electrogenic NHA as a function of the pHL and the membrane potential:

|

(3) |

Substitution of known parameters allows us to solve for the maximum pHL that can be generated to still enable the proper functioning of a NHA with varying pHi. The results shown in Table 1 demonstrate that an increase in pHi directly favors higher pHL values via the action of an apical NHA. At a pHi of 7.0, the maximum pHL that can be generated would only be pH 9.0. However, a pHi of 8.5 would allow for a pHL of 10.52, which falls within measured values for both in vivo and in vitro studies of these parameters and demonstrates the necessity for intracellular alkalinization to achieve the high pHL values. As mentioned above we are limited in our ability to accurately measure pHi above 8.6. However, in many traces, the noted fluorescence intensity was far above the highest calibration values, suggesting that the pHi of the anterior midgut does indeed reach levels far greater than 8.6. These extreme pHi values would allow an even greater alkaline pHL to exist.

Table 1.

Maximum pHL attainable as a function of intracellular pH using an apical electrogenic NBC coupled to a NHA

| pHi | Maximum pHL attainable |

|---|---|

| 7.0 | 9.02 |

| 7.5 | 9.52 |

| 8.0 | 10.02 |

| 8.5 | 10.52 |

| 9.0 | 11.02 |

The maximum pHL attainable refers to the pH in the lumen that could still theoretically allow an electrogenic Na+/H+ antiporter (NHA) to function in bringing H+ into the cell from the lumen. These calculated values assume [Na+]i=10 mmol l–1, luminal [Na+]=100 mmol l–1, and Vapi=–90 mV. NBC, Na+/HCO3– co-transporter

An important task for the future is to identify and characterize those transporters that are responsible for the transapical voltage, because this is a significant component of the transapical proton-motive force (see above). Finally, our finding of an extremely high pHi raises numerous questions about the challenges that this condition would place on other metabolic functions in this unique tissue and these questions will form the basis of future study.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- NBC

Na+/CO32– co-transporter

- NBCC

Na+/HCO3–/CO32– co-transporter

- NHA

Na+/H+ antiporter

- pHi

intracellular pH

- pHL

luminal pH

- Vapi

transapical potential

- Vbl

transbasal potential

- Vm

membrane potential

- Vte

transepithelial potential

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1-AI06346301). S.K.P. is funded by a Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGSD) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and an Honorary Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Scholarship. G.G.G. is supported by an NSERC Discovery grant. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Beyenbach, K. W., Pannabecker, T. L. and Nagel, W. (2000). Central role of the apical membrane H+-ATPase in electrogenesis and epithelial transport in Malpighian tubules. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 1459-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko, D. Y., Moroz, L. L., Harvey, W. R. and Linser, P. J. (2001a). Alkalinization by chloride/bicarbonate pathway in larval mosquito midgut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15354-15359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudko, D. Y., Moroz, L. L., Linser, P. J., Trimarchi, J. R., Smith, P. J. S. and Harvey, W. R. (2001b). In situ analysis of pH gradients in mosquito larvae using non-invasive, self-referencing, pH-sensitive microelectrodes. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 691-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T. M., Koch, A. and Moffett, D. F. (1999). The anterior and posterior `stomach' regions of larval Aedes aegypti midgut: regional specialization of ion transport and stimulation by 5-hydroxytryptamine. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T. M., Koch, A. and Moffett, D. F. (2000). The electrical properties of the anterior stomach of the larval mosquito (Aedes aegypti). J. Exp. Biol. 203, 1093-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T. M., Hutchinson, M. J., Heugel, K. L., Moffett, S. B. and Moffett, D. F. (2005). Additional morphological and physiological heterogeneity within the midgut of larval Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) revealed by histology, electrophysiology and effects of Bacillus thuringiensis endotoxin. Tissue Cell 37, 457-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corena, D. P. M., Seron, T. J., Lehman, H. K., Ochrietor, J. D., Kohn, A., Tu, C. and Linser, P. J. (2002). Carbonic anhydrase in the midgut of larval Aedes aegypti: cloning, localization and inhibition. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 591-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadd, R. H. (1975). Alkalinity within the midgut of mosquito larvae with alkaline-active digestive enzymes. J. Insect Physiol. 21, 1847-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoursey, T. H. (2003). Voltage-gated proton channels and other proton transfer pathways. Physiol. Rev. 83, 475-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow, J. A. T. (1984). Extremely high pH in biological systems: a model for carbonate transport. Am. J. Physiol. 246, R633-R635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, H. A. (1982a). Ion concentration and activity in the haemolymph of Aedes aegypti larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 101, 143-151. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, H. A. (1982b). Free amino acids as regulators of osmotic pressure in aquatic insect larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 101, 153-160. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, A. C. and Karet, F. E. (2007). Inherited renal acidoses. Physiology 22, 202-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, D. F. (1980). Voltage-current relation and K+ transport in tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta) midgut. J. Membr. Biol. 54, 213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, D. F. and Koch, A. R. (1988). Electrophysiology of K+ transport by midgut epithelium of lepidopteran insect larvae. II. The transapical electrochemical gradients. J. Exp. Biol. 135, 39-49. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, S. B. and Moffett, D. F. (2005). Comparison of immunoreactivity to serotonin, FMRFamide and SCPb in the gut and visceral nervous system of larvae, pupae and adults of the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Insect Sci. 5, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okech, B. A., Boudko, D. Y., Linser, P. J. and Harvey, W. R. (2008). Cationic pathway of pH regulation in larvae of Anopheles gambiae. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 957-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken, H., Moffett, S. B. and Moffett, D. F. (2004). The anterior stomach of larval mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti): effects of neuropeptides on transepithelial ion transport and muscular motility. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 3731-3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken, H., Moffett, S. B. and Moffett, D. F. (2008). Alkalinization in the isolated and perfused anterior midgut of the larval mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J. Insect Sci. 8, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannabecker, T. L., Aneshansley, D. J. and Beyenbach, K. W. (1992). Unique electrophysiological effects of dinitrophenol in Malpighian tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 263, R609-R614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, S. K., Tresguerres, M. and Goss, G. G. (2007). Interactions between Na+ channels and Na+/HCO3– cotransporters in the freshwater fish gill: a model for transepithelial Na+ uptake. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, 935-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, S. K., Tresguerres, M. and Goss, G. G. (2008). Theoretical considerations underlying Na+ uptake mechanisms in freshwater fishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 148, 411-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheault, M. R., Okech, B. A., Keen, S. B. W., Miller, M. M., Meleshkevitch, E. A., Linser, P. J., Boudko, D. Y. and Harvey, W. R. (2007). Molecular cloning, phylogeny and localization of AgNHA1: the first Na+/H+ antiporter (NHA) from a metazoan, Anopheles gambiae. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 3848-3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. E., VanEkeris, L. A. and Linser, P. J. (2007). Cloning and characterization of AgCA9, a novel α-carbonic anhydrase from Anopheles gambiae Giles sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 3919-3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Z., Linser, P. J. and Harvey, W. R. (1999). Antibody to H+ V-ATPase subunit E colocalizes with portasomes in alkaline larval midgut of a freshwater mosquito (Aedes aegypti). J. Exp. Biol. 202, 2449-2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]