ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES

This review examines the results of randomized controlled trials in which behavioral weight loss interventions, used alone or with pharmacotherapy, were provided in primary care settings.

DATA SOURCES

Literature search of MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, and EMBASE (1950-present). Inclusion criteria for studies were: (1) randomized trial, (2) obesity intervention in US adults, and (3) conducted in primary care or explicitly intended to model a primary care setting.

REVIEW METHODS

Both authors reviewed each study to extract treatment modality, provider, setting, weight change, and attrition. The CONSORT criteria were used to assess study quality. Due to the small number and heterogeneity of studies, results were summarized but not pooled quantitatively.

RESULTS

Ten trials met the inclusion criteria. Studies were classified as: (1) PCP counseling alone, (2) PCP counseling + pharmacotherapy, and (3) “collaborative” obesity care (treatment delivered by a non-physician provider). Weight losses in the active treatment arms of these categories of studies ranged from 0.1 to 2.3 kg, 1.7 to 7.5 kg, and 0.4 to 7.7 kg, respectively. Most studies provided low- or moderate-intensity counseling, as defined by the US Preventive Services Task Force.

CONCLUSIONS

Current evidence does not support the use of low- to moderate-intensity physician counseling for obesity, by itself, to achieve clinically meaningful weight loss. PCP counseling plus pharmacotherapy, or intensive counseling (from a dietitian or nurse) plus meal replacements may help patients achieve this goal. Further research is needed on different models of managing obesity in primary care practice.

KEY WORDS: obesity, primary care, health-care providers, counseling, drug therapy

Obesity is a root cause of numerous conditions treated by primary care providers (PCPs).1–3 Weight loss can improve health and reduce the risk of complications.4,5 The US Preventive Services Task Force (“Task Force”) has recommended that “clinicians screen all adult patients for obesity and offer intensive counseling and behavioral interventions to promote sustained weight loss for obese adults.”6 (Intensive counseling is defined as at least two visits per month for the first 3 months.) This clearly is a tall order, given that 32% of Americans are obese.7

The American Medical Association8 and the American College of Physicians9 also have published weight management guidelines for clinicians. However, numerous barriers exist to the provision of behavioral counseling by PCPs. They include practitioners’ lack of time, skills, resources, and reimbursement, as well as competing demands of the many other recommended preventive services.10–12 Moreover, most of the evidence for obesity treatment is derived from efficacy studies that were conducted in academic medical centers and that may have limited relevance for primary care.13 The Task Force acknowledged the potential difficulty of PCPs offering intensive weight loss counseling and suggested that practitioners consider referring patients for such care. The Task Force also concluded that the evidence was “insufficient to recommend for or against the use of moderate- or low-intensity counseling” (i.e., less than two visits per month).6

Practitioners and researchers know little about the efficacy of behavioral weight loss interventions that can be delivered in primary care practice.14,15 The primary goal of this review is to examine the results of studies that delivered behavioral counseling alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy.

METHODS

We examined studies of primary care-based weight loss interventions in US adults. Inclusion criteria included: (1) the study was a randomized controlled trial of a weight loss intervention in adults; (2) counseling was conducted by a PCP or another provider working in the primary care office (or the trial was implemented in a setting explicitly intended to simulate primary care); (3) the study was conducted in the US. Exclusion criteria included: (1) intervention trials that were not primary care-based; (2) non-US studies; (3) pediatric trials; (4) studies based in primary care and related to obesity but that were not intervention trials (e.g., surveys). We included only studies from the US because we wished to assess the effectiveness of interventions delivered in the context of this nation’s health-care system.16 Given the limited literature, studies were not excluded on the basis of sample size, treatment duration, or participants’ characteristics (e.g., presence of obesity co-morbidities).

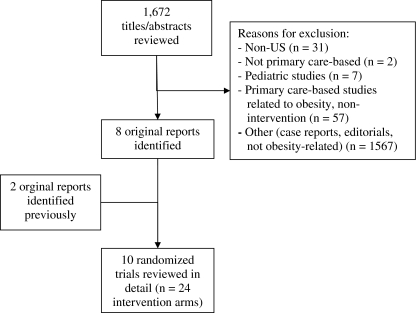

We searched databases that included PubMed (393 titles/abstracts reviewed), Medline (362), the Cochrane Library (33), EMBASE (705), and CINAHL (179), using the search terms “obesity OR obesity, morbid” and “primary health care” (for EMBASE; “primary medical care”). The search covered 1950 to the present (last updated January, 2009). Bibliographies of studies, as well as of prior qualitative and systematic reviews,13,15,17–21 also were examined to ensure completeness of the search. Quality of studies was rated using the CONSORT criteria, as well as questions from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.22,23 Each author reviewed the studies independently. No disagreements between the two authors occurred during data abstraction. Figure 1 outlines the literature search and shows that 1,672 abstracts were reviewed to find the 10 studies that met our inclusion criteria. Decisions about inclusion were made based on the abstract, except for eight additional studies that required review of the full manuscript. Weight losses abstracted from studies were based on intent-to-treat analyses, unless otherwise noted.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for review of the literature on primary care-based weight loss studies.

RESULTS

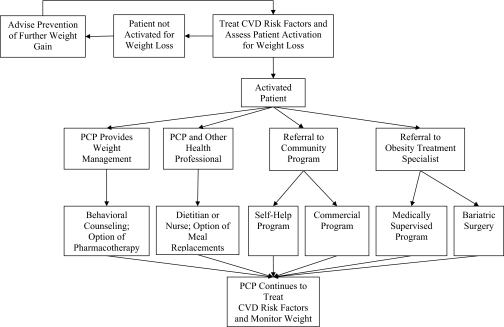

The review identified two principal approaches that have been tested for PCPs to manage obesity in their own practices (see Fig. 2). The first is for practitioners to provide behavioral weight loss counseling themselves, with or without the addition of pharmacotherapy. The second option, referred to as collaborative obesity management, uses a team approach in which a non-physician (e.g., registered dietitian) serves as the primary treatment provider, with the physician in a supporting role.24,25 Figure 2 presents these two approaches, along with referral options available to PCPs.

Figure 2.

An algorithm for identifying an appropriate weight loss option. After treating cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and assessing patients’ activation for weight loss, primary care providers (PCPs) may elect to offer behavioral counseling themselves (with or without pharmacotherapy) or to provide counseling in collaboration with other practice staff. Alternatively, PCPs may refer patients to community programs (e.g., Weight Watchers) or to obesity treatment specialists (e.g., medically supervised programs, bariatric surgery).

Characteristics of the Studies Reviewed

Of the ten studies that met inclusion criteria, only two met the Task Force’s recommendation for a high-intensity intervention (i.e., at least two visits per month for the first 3 months).26,27 Four other trials were moderate intensity (i.e., monthly contact),28–31 and the remaining four studies were low intensity.32–35 In the active treatment arms of the high-, medium-, and low-intensity studies, the mean number of treatment contacts was 17 (over 7.5 months), 14.8 (over 13.5 months), and 7.2 (over 16 months), respectively. Only one of the ten studies27 was conducted, in its entirety, after the publication of the Task Force’s recommendation. Six of the ten studies gave explicit descriptions of the training and supervision of PCPs during the trial.30–35 (In one of these studies, PCPs were not trained separately, but rather were given the same educational materials that were provided to patients.33) Of the ten studies, we rated two as good quality32,35 and the other eight as fair, according to the CONSORT criteria.26–31,33,34 High attrition (≥35%) was observed in several studies and in two trials26,27 was not accounted for by the use of intention-to-treat analysis (in which the baseline weight or last observed weight was carried forward for dropouts).

Treatment of Obesity by PCPs

PCP Counseling

Four trials have assessed the effects of brief physician counseling.30–32,34 Martin and colleagues30 tested a regimen of six monthly visits that PCPs provided their own patients. Patients had an average age of 41.7 years and body mass index (BMI) of 38.8 kg/m2; all were female, and most were African-American. Counseling materials were individualized for each patient. An intent-to-treat analysis revealed that the PCP counseling group lost an average of 1.4 kg at 6 months, compared to a gain of 0.3 kg in patients who received usual care (p = 0.01). As shown in Table 1, changes for the two groups at 18 months were -0.5 vs. +0.1 kg, respectively (p = 0.39). In a similar study, Christian et al.32 evaluated the effect of additional PCP counseling during quarterly visits for patients with type 2 diabetes. Patients had an average age of 53.2 years and BMI of 35.1 kg/m2; 67% were female, and 50% were Latino. Counseling was provided using lifestyle change goal sheets that were individualized to patients. Patients in the control group also had quarterly visits with their PCP, but did not receive the lifestyle change goal sheets. After 1 year, patients in the counseling group lost 0.1 kg, compared to a gain of 0.6 kg in the control group (p = 0.23). The odds of achieving a 5% weight loss were higher in the intervention group (p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Studies of Primary Care Provider (PCP) Counseling and PCP Counseling Plus Pharmacotherapy

| Study | N | Interventions | Number of visits | Weight change (kg) | Attrition (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief PCP counseling | |||||

| Martin 30 | 144 | (1) Usual care + monthly PCP visits | 6 | -0.5 | 44 |

| (2) Usual care | 0 | 0.1 | 23 | ||

| Christian 32 | 310 | (1) Quarterly PCP visits; lifestyle change goal sheets | 4 | -0.1 | 9 |

| (2) Quarterly PCP visits | 4 | 0.6 | 15 | ||

| Ockene 34† | 1,162 | (1) PCP training + office support | 3.6 | -2.3 | 37 |

| (2) PCP training | 3.1 | -1.0 | 42 | ||

| (3) Usual care | 3.4 | 0.0 | 42 | ||

| Cohen 31 | 30 | (1) Usual care + additional PCP visit | 12 | -0.9 | Not stated |

| (2) Usual care | 0 | 1.3 | |||

| Brief PCP counseling + pharmacotherapy | |||||

| Hauptman 33 | 796 | (1) Counseling + orlistat, 120 mg tid | 10 | -5.0 | 46 |

| (2) Counseling + orlistat, 60 mg tid | 10 | -4.5 | 44 | ||

| (3) Counseling | 10 | -1.7 | 57 | ||

| Poston 29 | 250 | (1) RD/RN counseling + orlistat, 120 mg tid | 13 | -1.7 | 34 |

| (2) Orlistat, 120 mg tid | 13 | -1.7 | 35 | ||

| (3) RD/RN counseling | 13 | 1.7 | 67 | ||

| Wadden 35‡ | 106 | (1) PCP counseling + sibutramine, 15 mg/day | 8 | -7.5 | 19 |

| (2) Sibutramine, 15 mg/day | 8 | -5.0 | 18 | ||

*Attrition is defined as the percentage of participants who did not contribute an in-person weight at the end of the study. An intention-to-treat analysis was used in most studies, except for two that used a completers’ analysis31, 34

†PCPs in groups 1 and 2 received 3 h of training to provide nutritional counseling to patients. Office support also included provision of dietary assessments to patients and counseling materials to PCPs, as well as flagging the results of dietary assessments during PCP visits. Patients were not required to attend a set number of office visits

‡The study by Wadden et al. included two additional groups, both of which included intensive group lifestyle modification. The results of these groups are not displayed here

Ockene et al. examined the benefits of brief PCP counseling among overweight and obese patients with hyperlipidemia.34 Patients had an average age of 49.3 and BMI of 28.7 kg/m2; 56% were women and 95% were Caucasian. A total of 45 PCPs were randomized to provide one of three interventions: (1) usual care, (2) physician nutrition counseling, or (3) physician nutrition counseling + office support for intervention delivery. Office support included provision of dietary assessments to patients and counseling materials to PCPs, as well as flagging the results of dietary assessments during PCP visits. As shown in Table 1, patients in these three groups were seen by their PCPs an average 3.4, 3.1, and 3.6 times during the trial, respectively. After 1 year, only the patients of physicians in the third arm achieved a statistically significant weight loss (2.3 kg) as compared to the control group (weight change of 0.0 kg; p < 0.001). Weight change in the second arm (1.0 kg) was not significantly different from that in the other two groups. In a similar investigation, Cohen et al. randomized resident physicians who were treating obese patients with hypertension to: (1) nutrition counseling training or (2) usual care.31 Patients had an average age of 59.5 years and BMI of 34.1 kg/m2; gender and ethnicity were not reported. Patients in the two groups were seen 9.7 and 5.2 times during the 1-year study. (Those in the intensive treatment arm were offered monthly visits.) Patients of PCPs that received nutrition counseling training lost 0.9 kg, while patients of PCPs in the control group gained 1.3 kg. The difference between groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05; exact p value not provided).

PCP Counseling plus Pharmacotherapy

Three studies have tested the effectiveness of lifestyle counseling plus pharmacotherapy provided by PCPs or as part of interventions that modeled brief office visits for obesity.29,33,35 A 2-year study of orlistat,33 conducted principally in PCP practices, randomized patients to placebo, orlistat 60 mg tid, or orlistat 120 mg tid. Patients had an average age of 42.5 years and BMI of 36.0 kg/m2; 72% were female and 89% were Caucasian. All patients received the same brief lifestyle counseling, which consisted of a calorie prescription, instruction in record keeping, written materials on weight management, and a series of four videotapes on lifestyle modification. In addition, patients were assessed by their PCPs ten times during the trial. As shown in Table 1, weight losses in the three groups after 2 years were 1.7 kg, 4.5 kg, and 5.0 kg, respectively (p = 0.001 for both orlistat groups compared with placebo). A second trial of orlistat was conducted in a research clinic but sought to simulate brief office visits for obesity.29 Patients had an average age of 41.0 years and BMI of 36.1 kg/m2; 92% were female, with 36% Caucasian, 38% African-American, and 26% Latino. They were randomized to: (1) monthly, 15–20 min weight loss counseling visits (conducted by a nurse or registered dietitian), (2) orlistat alone (120 mg tid), or (3) the combination of brief counseling visits plus orlistat. At 1 year, patients in the two groups that received orlistat both lost an average of 1.7 kg, while those in the counseling-alone group gained 1.7 kg (p < 0.001 for arms 2 and 3, compared to arm 1).

In another medication study, PCPs provided: (1) sibutramine alone (15 mg/day), with eight brief visits over 1 year to monitor blood pressure and pulse, or (2) sibutramine (15 mg/day) plus brief lifestyle counseling, provided during the eight visits.35 Patients had an average age of 43.6 years and BMI of 37.9 kg/m2; 80% were female, with 68% Caucasian, 27% African-American, and 5% Latino. Those in the sibutramine + brief counseling group were required to keep food and activity records for the first 18 weeks, at which time they lost significantly more weight than individuals treated by sibutramine alone (7.5 vs 5.0 kg, respectively; p = 0.05). Weight losses of the two groups were 7.3 and 4.7 kg at 1 year (p > 0.1).

Collaborative Obesity Treatment

Three studies have evaluated collaborative obesity care, in which registered dietitians or nurses were enlisted to support PCPs’ provision of weight loss counseling.26–28 Patients studied by Ashley et al.26 were randomly assigned to one of three arms: (1) every-other-week counseling by a registered dietitian (RD), (2) every-other-week counseling by a RD, plus meal replacements, or (3) every-other-week visits with a nurse or physician, plus meal replacements. Patients had an average age of 40.4 years and BMI of 30.0 kg/m2; all were female. (Ethnicity was not reported.) As shown in Table 2, weight losses at 1 year in the three groups were 3.4, 7.7, and 3.5 kg, respectively (p = 0.03 for group 2, as compared to groups 1 and 3), suggesting that meal replacements and RD counseling had an additive effect.

Table 2.

Studies of Collaborative Obesity Treatment

| Study | N | Interventions | Number of visits | Weight change (kg) | Attrition (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashley 26 | 113 | (1) Registered dietitian (RD) counseling | 26 | -3.4 | 38 |

| (2) RD counseling + meal replacements | 26 | -7.7 | 32 | ||

| (3) MD/RN counseling + meal replacements | 26 | -3.5 | 34 | ||

| Ely 27 | 101 | (1) Patient and PCP education + telephone calls + treatment recommendations given to PCP | 8 | -4.3 | 48 |

| (2) Patient and PCP education | 0 | -1.0 | 52 | ||

| Logue 28 | 665 | (1) Brief in-person counseling + telephone calls | 28 | -0.4 | 31 |

| (2) Brief in-person counseling | 4 | -0.2 | 38 |

Ely et al.27 randomized 101 patients in three rural primary care practices to: (1) educational materials or (2) educational materials, plus a series of eight phone calls from a masters-level counselor who used motivational interviewing techniques for weight management. Patients had an average age of 49.5 years and BMI of 36.0 kg/m2; 77% were female, with 87% Caucasian, 7% Latino, and 6% African-American. PCPs of patients in both groups also were given educational materials, and PCPs of patients in the active treatment group were provided with obesity care recommendations (based on information obtained from phone calls). Weight losses after 6 months were 1.0 and 4.3 kg, respectively (p = 0.01). In a similar study, Logue et al.28 randomized primary care patients to an intervention delivered by RDs or to a usual care arm. Patients ranged in age from 40–69 years, and just under half had a BMI ≥35 kg/m2. (Means were not given for these values.) Sixty-eight percent were female, with 73% Caucasian and 27% African-American. Patients in both groups received calorie and exercise prescriptions, as well as semi-annual 10-min visits with a RD. Those in the first group additionally received monthly telephone calls from a RD. Weight losses after 6 months in the two groups were 1.6 and 0.9 kg (estimated from a figure), but both interventions were associated with minimal weight losses after 2 years (0.4 and 0.2 kg, respectively; p = 0.5).

DISCUSSION

Results of this review reveal how little research has been conducted on the management of obesity in primary care practice. Of the ten studies that met criteria for inclusion, only two met the Task Force’s recommendation of providing a high-intensity intervention (at least two visits per month for the first 3 months).26,27 One of these two studies incorporated collaborative obesity treatment in which a dietitian met with patients twice a month and provided meal replacements.26 Participants lost 7.7 kg, which met the criterion of clinically significant weight loss (i.e., ≥5% of initial weight). The other high-intensity trial, which provided twice monthly contact by phone for the first 3 months, produced a loss of 4.3 kg.27 Weight loss, however, in this latter study was calculated from a completers analysis (based on 50% of participants) and is likely to overestimate the efficacy of the intervention. Of the remaining eight trials, four were of moderate intensity (at least one counseling visit per month), and four were of low intensity (<1 visit per month). Two of the four low-intensity studies produced a clinically significant weight loss by combining lifestyle counseling with either sibutramine or orlistat.33,35 Of the three studies that combined counseling and pharmacotherapy, two trials sought explicitly to simulate brief primary care office visits but were conducted in research clinics.29,35 Thus, the results of these studies must be interpreted with caution.

None of the four studies in which PCPs provided low- to moderate-intensity behavioral counseling alone30–32,34 resulted in clinically significant weight loss. Weight losses in the active treatment arms of these trials ranged from 0.1 kg to 2.3 kg. The Task Force gave low- and moderate-intensity behavioral counseling an “I” recommendation (insufficient evidence for or against). The results of this review suggest that low- and moderate-intensity counseling, delivered by a PCP alone, is unlikely to result in clinically significant weight loss.

As noted previously, all but one of the ten trials reviewed here were conducted prior to the Task Force’s recommendation for high-intensity counseling. This recommendation was based largely on the results of efficacy trials, such as the Diabetes Prevention Program, that were conducted in academic medical centers. The time, effort, and expense required for PCPs to provide such care would appear to be prohibitive for most practitioners in the absence of adequate reimbursement and with the already pressing demands of office practice.36–38 However, further research clearly is warranted to assess the results of PCPs’ providing high-intensity behavioral counseling, as recommended by the Task Force. Studies should include economic analyses to determine the costs and cost-effectiveness of such care as compared to self-help (e.g., Take off Pounds Sensibly) and commercial (e.g., Weight Watchers) programs.

The selection criteria for this review were not designed to capture studies in which the PCP may elect to play a more supportive or consultative role (e.g., assess, agree, advise, assist, arrange) and refer patients to more intensive weight loss interventions that are delivered outside of primary care settings. These treatment options have been summarized in detail in previous reviews.21,39–44 Commercial programs, such as Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig, have been shown to produce weight losses of 5 to 7% of initial weight.45,46 Intensive behavioral treatments provided in academic medical centers, such as in the Diabetes Prevention Program,4 can help patients achieve a weight loss of 7–10%.47 Medically supervised programs (OPTIFAST, Health Management Resources) may induce losses of 15–25% of initial weight using meal replacements,48–52 although patients have difficulty sustaining losses of this size, even when provided weight maintenance therapy.48,51,53 Pharmacotherapy (e.g., orlistat, sibutramine), when prescribed alone, produces modest losses of 4 to 5% of initial weight.54 However, interventions that combine pharmacotherapy with intensive lifestyle modification may induce losses of 8–12% of initial weight.35,55–57 Medication must be taken long-term to maintain weight loss.56,58 Bariatric surgery is the most effective method of inducing and maintaining weight loses of 15% (gastric banding) to 25% (gastric bypass).40,42 Surgery has been shown to ameliorate (or fully control) co-morbid conditions, particularly type 2 diabetes,40,59 and in a matched cohort study, to reduce mortality.60 Surgery also carries the highest risks of complications, including peri-operative mortality.61

PCPs who elect not to provide behavioral weight counseling themselves must still play a critical role in assessing and treating obesity-related cardiovascular risk factors. Tight control of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia—all of which are common among overweight and obese individuals—is associated with reductions in morbidity and mortality.62–65 A recent paper underscored the importance of treating CVD risk factors in overweight and obese individuals.66

Once they have evaluated and treated obesity-related risk factors, PCPs can identify the most favorable weight management options for a given patient. In addition to guidance provided by the American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute devised an algorithm for obesity treatment based on BMI and on the patient’s number of CVD risk factors.5 Options range from a comprehensive program of lifestyle modification (i.e., diet, exercise, and behavior therapy) to bariatric surgery. PCPs who work in integrated health-care systems may have access to this range of weight management interventions.67–71 Those who do not have such access in their practice settings can refer patients to commercial or self-help programs or to weight loss specialists, as described above.

Research on the management of obesity in primary care is in its infancy. Little is known about the clinical and cost-effectiveness of weight management provided by PCPs. Results of this review suggest that: (1) low-intensity PCP counseling alone is insufficient for achieving clinically meaningful weight loss in obese adults, and (2) available data do not indicate how best to incorporate PCPs into more intensive approaches (e.g., collaborative treatment) to achieve this goal. More research is needed on collaborative interventions that involve other members of the clinical care team, as well as call centers and other community linkages.72,73 Without more effective therapies, greater resources in their practices, and more adequate reimbursement,74,75 PCPs alone cannot be expected to provide effective weight management for all of their patients who require it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preparation of this manuscript was supported, in part, by NIH grants U01-HL087072, DK065018, and 5-K12-HD043459–04. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the review or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Potential conflict of interest Dr. Tsai served from 2006–2008 as an unpaid consultant to a medically supervised low-calorie diet program at the University of Pennsylvania that uses products manufactured by Health Management Resources.™ Dr. Wadden serves as an unpaid consultant to the same program. He has previously served (but not since 2005) as a consultant to Novartis Nutrition, which manufactures OPTIFAST™, and to Abbott Laboratories, which markets sibutramine (Meridia™).

REFERENCES

- 1.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:915–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Oster G, Edelsberg J, O’Sullivan AK, Thompson D. The clinical and economic burden of obesity in a managed care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:681–9. [PubMed]

- 4.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults—The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed]

- 6.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:930–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kushner RF. Roadmaps for clinical practice: case studies in disease prevention and health promotion—assessment and management of adult obesity: a primer for physicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2003.

- 9.Bray GA, Wilson JF. In the clinic. Obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:ITC4–1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med. 2004;79:156–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kushner RF. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995;24:546–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2007: recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed January 30, 2008, at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm.

- 13.McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, et al. Screening and interventions for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:933–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Blackburn GL, Greenberg I, Day KM, McNamara A, Fischer SG. Small steps and practical approaches to the treatment of obesity. Medscape Internal Medicine. Accessed August 7th, 2008, at: http://www.medscape.com/viewprogram/8204

- 15.Anderson DA, Wadden TA. Treating the obese patient. Suggestions for primary care practice. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:156–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Levi J, Segal LM, Gadola E. F as in Fat: how obesity policies are failing in America. Trust for America’s Health; 2007.

- 17.Hill JO, Wyatt H. Outpatient management of obesity: a primary care perspective. Obes Res. 2002;10:124S–130S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lyznicki JM, Young DC, Riggs JA, Davis RM. Obesity: assessment and management in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:2185–96. [PubMed]

- 19.Thompson WG, Cook DA, Clark MM, Bardia A, Levine JA. Treatment of obesity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:93–101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Dansinger ML, Tatsioni A, Wong JB, Chung M, Balk EM. Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, et al. Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:532–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods guide for comparative effectiveness reviews. Rockville, MD; 2007: Accessed January 5th, 2009, at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/repFiles/2007_10DraftMethodsGuide.pdf. [PubMed]

- 24.Frank A. A multidisciplinary approach to obesity management: the physician’s role and team care alternatives. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:S44–S48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Adelman AM, Graybill M. Integrating a health coach into primary care: reflections from the Penn State Ambulatory Care Research Network. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:S33–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Ashley JM, St Jeor ST, Schrage JP, et al. Weight control in the physician’s office. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1599–1604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ely AC, Banitt A, Befort C, et al. Kansas primary care weighs in: a pilot randomized trial of a chronic care model program for obesity in three rural Kansas primary care practices. J Rural Health. 2008;24:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Logue E, Sutton K, Jarjoura D, Smucker W, Baughman K, Capers C. Transtheoretical model-chronic disease care for obesity in primary care: a randomized trial. Obes Res. 2005;13:917–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Poston WS, Haddock CK, Pinkston MM, et al. Evaluation of a primary care-oriented brief counselling intervention for obesity with and without orlistat. J Intern Med. 2006;260:388–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Martin PD, Dutton GR, Rhode PC, Horswell RL, Ryan DH, Brantley PJ. Weight loss maintenance following a primary care intervention for low-income minority women. Obesity. 2008;16:2462–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Cohen MD, D’Amico FJ, Merenstein JH. Weight reduction in obese hypertensive patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:25–8. [PubMed]

- 32.Christian JG, Bessesen DH, Byers TE, Christian KK, Goldstein MG, Bock BC. Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:141–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Hauptman J, Lucas C, Boldrin MN, Collins H, Segal KR. Orlistat in the long-term treatment of obesity in primary care settings. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:160–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, et al. Effect of physician-delivered nutrition counseling training and an office-support program on saturated fat intake, weight, and serum lipid measurements in a hyperlipidemic population: Worcester Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia (WATCH). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:725–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2111–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Donahoo WT, Hill JO. What will it take to get reimbursement for obesity? Obesity Management. 2007;3:193–5. [DOI]

- 37.Tsai AG, Asch DA, Wadden TA. Insurance coverage for obesity treatment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1651–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Arterburn DE, Crane PK, Veenstra DL. The efficacy and safety of sibutramine for weight loss: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:994–1003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Hutton B, Fergusson D. Changes in body weight and serum lipid profile in obese patients treated with orlistat in addition to a hypocaloric diet: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1461–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Maggard MA, Shugarman LR, Suttorp M, et al. Meta-analysis: surgical treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:547–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.O’Meara S, Riemsma R, Shirran L, Mather L, ter Riet G. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of orlistat used for the management of obesity. Obes Rev. 2004;5:51–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Systematic review: an evaluation of major commercial weight loss programs in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, et al. Weight loss with self-help compared with a structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1792–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Rock CL, Pakiz B, Flatt SW, Quintana EL. Randomized trial of a multifaceted commercial weight loss program. Obesity. 2007;15:939–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2226–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Anderson J, Vichitbandra S, Qian W, Kryscio R. Long-term weight maintenance after an intensive weight-loss program. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999;18:620–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Anderson JW, Grant L, Gotthelf L, Stifler LT. Weight loss and long-term follow-up of severely obese individuals treated with an intense behavioral program. Int J Obes. 2007;31:488–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Donnelly JE, Smith BK, Dunn L, et al. Comparison of a phone vs clinic approach to achieve 10% weight loss. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1270–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA. One-year behavioral treatment of obesity: comparison of moderate and severe caloric restriction and the effects of weight maintenance therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA, Stunkard AJ. A multicenter evaluation of a proprietary weight reduction program for the treatment of marked obesity. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:961–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Mathus-Vliegen EM. Long-term maintenance of weight loss with sibutramine in a GP setting following a specialist guided very-low-calorie diet: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:S31–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Davidson MH, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, et al. Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;281:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.James WP, Astrup A, Finer N, et al. Effect of sibutramine on weight maintenance after weight loss: a randomised trial. STORM Study Group. Sibutramine Trial of Obesity Reduction and Maintenance. Lancet. 2000;356:2119–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Sarwer DB, Prus-Wisniewski R, Steinberg C. Benefits of lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:218–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Sjostrom L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for weight loss and prevention of weight regain in obese patients. European Multicentre Orlistat Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352:167–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Vetter ML, Cardillo S, Rickels MR, Iqbal N. Narrative review: effect of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JA, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1903–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Ross SD, Allen IE, Connelly JE, et al. Clinical outcomes in statin treatment trials: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1793–1802. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Thavendiranathan P, Bagai A, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases with statin therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2307–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Cadwell BL, et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors according to body mass index in US adults. JAMA. 2005;293:1868–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Brelje K, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: Weigh-To-Be 1-year outcomes. Int J Obes. 2003;27:1584–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, Pronk NP, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: Weigh-To-Be 2-year outcomes. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1565–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Wylie-Rosett J, Swencionis C, Ginsberg M, et al. Computerized weight loss intervention optimizes staff time: the clinical and cost results of a controlled clinical trial conducted in a managed care setting. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:1155–62, quiz 1163–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Veterans Affairs National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Motivating Overweight and Obese Veterans Everywhere (MOVE). Accessed December 15, 2008, at: http://www.move.va.gov.

- 71.Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute. Kaiser Permanente Weight Management Initiative. Accessed January 15, 2009, at: http://www.kpcmi.org/weight-management/index.html.

- 72.Wee CC, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Stage of readiness to control weight and adopt weight control behaviors in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:410–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:357–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Allison DB, Downey M, Atkinson RL, et al. Obesity as a disease: a white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the council of the obesity society. Obesity. 2008;16:1161–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Nonas CA. A model for chronic care of obesity through dietary treatment. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:S16–S22. [DOI] [PubMed]