ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Prior studies evaluating racial/ethnic differences in responses to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among HIV-infected patients have not adequately accounted for many potential confounders, and few have included Hispanic patients.

OBJECTIVE

To identify racial/ethnic differences in ART adherence, and risk of AIDS and death after ART initiation for HIV patients with similar access to care.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS

4,686 HIV-infected patients (66% White, 20% Black, and 14% Hispanic) initiating ART and who were enrolled in an integrated healthcare system.

MEASUREMENTS

Main outcomes evaluated were ART adherence, new AIDS clinical events, and all-cause mortality. The potential confounding effects of demographics, socioeconomic status, ART parameters, HIV disease stage, and other clinical parameters were considered in multivariable models.

RESULTS

Adjusted mean adherence levels were higher among White (70.1%; ref) compared with Black (64.2%; < 0.001) and Hispanic patients (65.2%; < 0.001). Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for the risk of new AIDS events (White patients as reference) were 1.3 ( = 0.09) for Black and 0.9 ( = 0.64) for Hispanic patients. The adjusted HR for AIDS comparing Hispanic to Black patients was 0.7 ( = 0.11). Hispanic patients had fewer deaths compared with other racial/ethnic groups, particularly cancer and cardiovascular-related. However, adjusted HRs for death were 1.2 ( = 0.37) and 0.9 ( = 0.62) for Black and Hispanic patients, respectively, compared with White patients and 0.9 ( = 0.63) for Hispanic compared with Black patients. Adjustment for adherence did not change inferences for AIDS or death.

CONCLUSIONS

In the setting of similar access to care, we did not observe a disparity for the risk of clinical events for racial/ethnic minorities, despite lower ART adherence.

KEY WORDS: race, ethnicity, AIDS, survival

INTRODUCTION

Black and Hispanic persons account for a disproportionate proportion of HIV/AIDS cases in the United States.1 In 2005, rates of HIV/AIDS were highest in these racial/ethnic minority groups compared with others, with rates per 100,000 population of 71.3 for black and 27.8 for Hispanic persons.2 Furthermore, 2003 US mortality statistics indicated HIV/AIDS was the third and fourth leading cause of death among those 35 to 44 years of age for black and Hispanic persons, respectively, compared with sixth for White persons in this age group.3

These racial/ethnic disparities underscore the public health obligation to provide equal access to care for the diagnosis and treatment of HIV infections. However, it is not firmly established whether equal access for HIV-infected persons would result in similar clinical outcomes among racial/ethnic groups. Others have investigated differences in the risk of AIDS or death by race/ethnicity,4–12 but few have included Hispanic patients.4,10,11,13 Most studies have reported no racial/ethnic differences in clinical progression of HIV,4–10,13 although 1 large study indicated that Black and Hispanic patients had higher mortality rates compared with White patients,11 and another indicated higher mortality rates for Hepatitis C co-infected White compared with Black patients.12 However, studies were limited by small sample sizes for certain racial/ethnic subgroups,4,6,9,10,12,13 and limited7,8,11 or no adjustment9,12 for potential confounders.

The Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) HIV patient population offers unique advantages for a more comprehensive analysis on this topic. First, certain attributes of care at KPNC may contribute to reduced racial/ethnic differences in outcomes. Specifically, all patients have comprehensive medical insurance coverage, and thus outcome differences attributable to variations in access to care are reduced. In addition, HIV care in KPNC is guided by the principles of integrated, chronic condition management and multidisciplinary HIV specialty care. A second advantage of this setting is the large HIV registry with historical data on more than 17,000 patients, including a substantial number of racial/ethnic minorities. The comprehensive clinical and administrative databases allow for more complete consideration of potential confounding factors such as socioeconomic status, HIV disease stage, and ART adherence.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study for years 1996 to 2005 of adult HIV-infected patients initiating ART within KPNC, a large integrated health care system providing comprehensive medical services for over 3 million members (representing ~30% of insured Northern Californians14). Our main objectives were to measure racial/ethnic differences in ART adherence, new AIDS events, and all-cause mortality after ART initiation.

The study population consisted of White (i.e., non-Hispanic White), Black (i.e., non-Hispanic African-American, or African immigrants), and Hispanic HIV-infected patients at least 18 years of age or older who initiated ART in KPNC and who had at least 6 months of health plan membership before ART initiation (i.e., to ensure that patients were initiating ART in KPNC). ART was defined as a regimen containing 3 or more antiretrovirals.15 Among 10,210 adult HIV-infected patients followed in KPNC between 1996 and 2005, 7,263 were prescribed ART. Study exclusions were 591 patients with unknown race/ethnicity, 341 in racial/ethnic categories with small sample sizes (265 Asian/Pacific Islander, 76 other), and 1,629 patients with less than 6 months of prior membership, resulting in a study population of 4,686 patients.

Data Sources

As described in prior studies,16,17 the KPNC HIV registry includes all known cases dating back to the early 1980s (17,630 cumulative cases through 2005). The HIV registry contains data on sex, birth date, race/ethnicity, HIV transmission risk factor (i.e., men who have sex with men, injection drug use, heterosexual sex, other, unknown), dates of known HIV infection, and AIDS diagnoses obtained from review of electronic and paper medical records. KPNC also maintains complete and historical databases on member demographics, prescriptions, hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and laboratory tests, including CD4 T-cell count and HIV RNA test results. Date and cause of death are identified from hospitalizations, membership files, California death certificates, and Social Security Administration data sets. Medical records were reviewed by the collaborating HIV clinician (MAH) to confirm causes of death.

Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence

We measured ART refill adherence using previously described and validated methods.18 Briefly, for each individual antiretroviral drug in a regimen, we computed the percent of total days between refills with pills available. Adherence estimates for individual antiretrovirals were averaged over all drugs in a regimen. The metric for ART adherence was thus the percentage of days with antiretroviral medication coverage between refills for a particular medication that was averaged for all antiretrovirals prescribed during an interval, and could have values between 0% and 100%. For ART adherence as an outcome, we computed ART adherence over a maximum of 2 years after ART initiation. For AIDS and death, with adherence as a predictor, we computed time-updated adherence between 2 clinic visits at least 3 months apart.

Clinical Endpoints

The primary endpoints examined were all-cause mortality and new clinical AIDS-defining events (1993 CDC AIDS criteria19 [excluding the CD4 < 200 criterion]) that resulted in a hospitalization. We also examined changes in HIV-related laboratory parameters by race including CD4 T-cell counts and time to HIV RNA levels of less than 500 copies/mL. Patients were followed until the earliest of either an outcome of interest, KPNC unenrollment, or December 31, 2005 (the end of follow-up).

Statistical Methods

Our primary predictor of interest was race/ethnicity categorized as White, Black, and Hispanic. We compared descriptive statistics at ART initiation by race/ethnicity using Pearson’s chi-square statistic for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

Next, we compared mean adherence levels by race/ethnicity using linear regression . Multivariable model selection involved an approach described previously20,21 that included baseline variables with univariate tests of association with race/ethnicity that were significant at < 0.25 as well as variables of known clinical importance. Potential confounding variables considered were age, sex, HIV transmission risk factor, 2000 census-based measures of lower education (i.e., ≥25% in census tract <high school diploma), lower income (i.e., ≥20% in census tract below poverty line), public health insurance (Medicaid or Medicare), ART initiation year (to adjust for temporal trends), ART class, antiretroviral naïve or experienced, years of known HIV-infected, prior AIDS, Hepatitis C co-infection, baseline CD4 T-cell counts, baseline HIV RNA levels, outpatient depression diagnoses, and a modified Charlson comorbidity index34 (excluding HIV/AIDS).

We next computed racial/ethnic specific incidence rates for death and new AIDS events. We used the Kaplan-Meier estimator and Cox proportional hazards regression models22 to analyze time to death or first AIDS event by race/ethnicity. Variables analyzed and the method for selecting the final multivariable model was the same as for adherence. We also considered a model additionally adjusted for time-updated ART adherence.

We further compared racial/ethnic differences in time to HIV RNA levels of less than 500 cp/mL through 2 years using Kaplan Meier plots and Cox regression,22 and changes in CD4 T-cell counts through 6 years using generalized estimating equation (GEE) methods,23 allowing for a change in slope at 1 year after ART initiation. Finally, we included covariates for time-updated CD4 and HIV RNA in models for AIDS and death to determine if these had an intermediate effect.

Analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), using proc GLM for linear regression, proc PHREG for Cox models, and proc GENMOD for GEE. The institutional review board at KPNC approved this study including a waiver of informed consent.

RESULTS

The study population consisted of 3,106 White, 919 Black, and 661 Hispanic patients. White patients, compared with Black or Hispanic patients, were older, had longer follow-up, had more years of known HIV-infection, and were more likely to be antiretroviral experienced, report being men who have sex with men, and have a depression diagnosis (Table 1). Many of these differences likely reflect the more recent HIV/AIDS epidemic in Black and Hispanic compared with White individuals.24 Black and Hispanic patients were also more likely to live in census tracts with lower education and income levels, and Hispanic patients were less likely to have public health insurance. Mean adherence levels over 2 years of ART in multivariable models were 70.1% for White, 64.2% for Black ( < 0.001 compared with White patients), and 65.2% for Hispanic ( < 0.001 compared with White patients and = 0.51 compared with Black patients) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics at Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy by Race/Ethnicity

| Parameter | White ( = 3,106) | Black ( = 919) | Hispanic ( = 661) | a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median years follow-up (IQR) | 4.7 (1.7, 8.0) | 3.4 (1.4, 6.6) | 3.5 (1.4, 6.6) | <0.001 |

| Male, % | 93.2 | 76.4 | 90.5 | <0.001 |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 42 (36, 49) | 41 (35, 48) | 37 (33, 44) | <0.001 |

| Median year ART initiation (IQR) | 1998 (96, 01) | 1999 (97, 02) | 1999 (97, 02) | <0.001 |

| HIV risk factor, % | <0.001 | |||

| Men who have sex with men | 70.7 | 41.2 | 61.6 | |

| Injection drug use | 7.0 | 9.0 | 5.8 | |

| Heterosexual sex | 9.7 | 32.4 | 19.5 | |

| Other/Unknown | 12.6 | 17.3 | 13.2 | |

| ≥25% in census tract <high school diploma, % | 15.8 | 36.1 | 38.4 | <0.001 |

| ≥20% in census tract below poverty line, % | 12.7 | 26.7 | 19.2 | <0.001 |

| Public health insurance (Medicaid or Medicare), % | 12.4 | 10.2 | 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Median years (IQR) known HIV+ | 5.6 (1.4, 8.8) | 3.0 (0.3, 7.2) | 2.6 (0.2, 6.6) | <0.001 |

| Median CD4 T-cells/µL (IQR) | 234 (101, 377) | 186 (55, 325) | 212 (81, 355) | <0.001 |

| Median log10 HIV RNA c/mL (IQR) | 4.4 (3.5, 5.0) | 4.5 (3.6, 5.0) | 4.5 (3.6, 5.1) | 0.23 |

| Prior AIDS diagnosis, % | 58.0 | 59.6 | 58.3 | 0.66 |

| Prior use of antiretrovirals, % | 51.3 | 39.4 | 35.7 | <0.001 |

| PI-based ART regimen class, % | 65.6 | 59.2 | 61.3 | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis C co-infection, % | 9.6 | 14.8 | 7.6 | <0.001 |

| Depression diagnosis, % | 21.4 | 13.3 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Mean Charlson comorbidity index scoreb | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.07 |

antiretroviral therapy, interquartile range

a Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis for continuous variables.

b Modified Charlson comorbidity index which excludes HIV or AIDS-related outcomes.

Table 2.

Differences in Percent Adherence in 24 Months After ART Initiation by Race/Ethnicity

| Adherencea | (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||

| Black (ref=White) | −4.6% | (−6.5, −2.7) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (ref=White) | −1.7% | (−3.9, 0.5) | 0.13 |

| Adjustedb | |||

| Black (ref=White) | −5.8% | (−8.1, −3.6) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (ref=White) | −4.9% | (−7.3, −2.5) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 4.2% | (1.2, 7.2) | 0.006 |

| Age (10 years) | 2.9% | (1.9, 3.8) | <0.001 |

| Year ART initiation (1 yr) | 1.4% | (1.1, 1.8) | <0.001 |

| Not MSM | −0.6% | (−2.6, 1.3) | 0.53 |

| Low education census tract | −1.3% | (−3.4, 0.8) | 0.21 |

| Low income census tract | −0.8% | (−3.2, 1.6) | 0.52 |

| Public health insurance | −4.8% | (−7.7, −2.0) | <0.001 |

| Pre-ART CD4 (100 cells) | 0.3% | (−0.2, 0.7) | 0.24 |

| Pre-ART HIV RNA (1 log) | −1.1% | (−2.1, 0.0) | 0.04 |

| Prior ART experience | −8.2% | (−10.3, −6.2) | <0.001 |

| PI-sparing ART class | 4.2% | (2.4, 6.1) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | −5.7% | (−8.0, −3.4) | <0.001 |

| Depression diagnosis | −2.0% | (−4.1, 0.0) | 0.06 |

| Charlson scorec 1–2 (ref = 0) | −0.8% | (−3.0, 1.3) | 0.45 |

| Charlson scorec ≥3 (ref = 0) | −5.3% | (−12.8, 2.2) | 0.17 |

antiretroviral therapy, confidence interval, hazard ratio, men who have sex with men, protease inhibitor

a Difference in % adherence compared with reference group.

b Multivariable model includes all parameters listed.

c Modified Charlson comorbidity index which excludes HIV or AIDS-related outcomes.

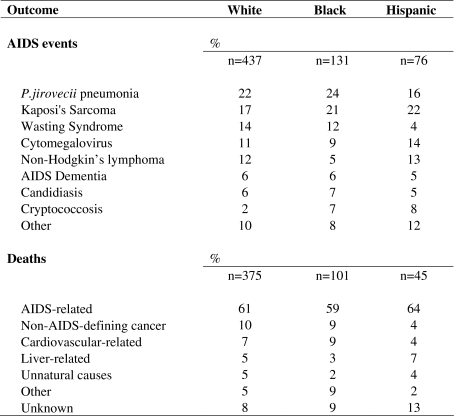

We observed 644 total hospitalizations for clinical AIDS: 437 events among White patients (31.9/1,000 person-years), 131 events among Black patients (38.0/1,000 person-years), and 76 among Hispanic patients (30.6/1,000 person-years). Overall, the most common events were Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, wasting syndrome, cytomegalovirus, and nonHodgkin’s lymphoma (Table 3). Few differences by race/ethnicity were observed for specific AIDS-defining events, although Hispanic patients had a low frequency of wasting syndrome and Black patients had a low frequency of nonHodgkin’s lymphoma.

Table 3.

Distribution of AIDS Events and Causes of Death by Race/Ethnicity

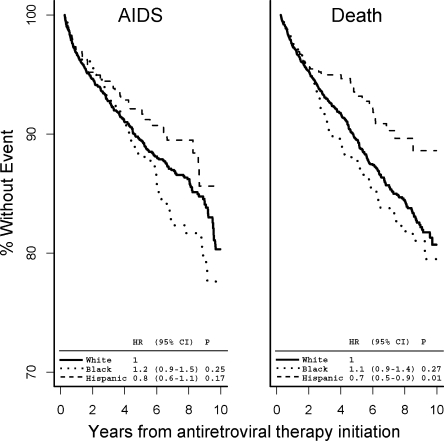

Although there was some suggestion that Black patients had the highest and Hispanic patients the lowest risk of any new AIDS event (Fig. 1, left panel), the corresponding unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) were not statistically significant. Inferences by race/ethnicity did not change in multivariable models, with adjusted HRs of 1.3 (95% CI: 1.0, 1.9; = 0.09) and 0.9 (95% CI: 0.6, 1.4) for Black and Hispanic patients, respectively compared with White patients (Table 4), and 0.7 (95% CI: 0.4, 1.1) for Hispanic compared with Black patients. With additional adjustment for ART adherence, the adjusted HRs were 1.2 (95% CI: 0.9, 1.8) and 0.9 (95% CI: 0.6, 1.3) for Black and Hispanic patients, respectively compared with White patients, and 0.7 (95% CI: 0.5, 1.0; = 0.051) comparing Hispanic and Black patients.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to AIDS and death by race/ethnicity. Kaplan-Meier curves for time to clinical AIDS (left panel) and time to death (right panel) over 10 years of antiretroviral therapy are presented. Hazard ratios (HR), 95% CIs, and -values are also presented.

Table 4.

Race/Ethnicity and Time to New AIDS Hospitalization or Death

| New AIDS event | Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | |||

| Unadjusted | ||||||

| Black (ref=White) | 1.15 | (0.91, 1.46) | 0.25 | 1.14 | (0.91, 1.43) | 0.27 |

| Hispanic (ref=White) | 0.80 | (0.58, 1.10) | 0.17 | 0.66 | (0.48, 0.92) | 0.01 |

| Adjusteda | ||||||

| Black (ref=White) | 1.33 | (0.95, 1.86) | 0.09 | 1.17 | (0.83, 1.66) | 0.37 |

| Hispanic (ref=White) | 0.90 | (0.58, 1.40) | 0.64 | 0.90 | (0.58, 1.38) | 0.62 |

| Male sex | 0.98 | (0.60, 1.62) | 0.95 | 1.61 | (0.94, 2.76) | 0.08 |

| Age (10 years) | 1.22 | (1.05, 1.41) | 0.008 | 1.43 | (1.25, 1.64) | <0.001 |

| Year ART initiation (1 year) | 1.00 | (0.93, 1.07) | 0.92 | 0.91 | (0.85, 0.98) | 0.02 |

| Not MSM | 0.81 | (0.59, 1.12) | 0.21 | 1.17 | (0.87, 1.57) | 0.29 |

| Low education census tract | 0.74 | (0.54, 1.02) | 0.06 | 0.85 | (0.62, 1.15) | 0.28 |

| Low income census tract | 1.01 | (0.70, 1.46) | 0.94 | 0.78 | (0.53, 1.15) | 0.22 |

| Public health insurance | 1.69 | (1.18, 2.42) | 0.005 | 1.78 | (1.28, 2.48) | <0.001 |

| Pre-ART CD4 (100 cells) | 0.87 | (0.78, 0.97) | 0.009 | 0.83 | (0.75, 0.92) | <0.001 |

| Pre-ART HIV RNA (1 log) | 1.70 | (1.41, 2.06) | <0.001 | 1.15 | (0.98, 1.36) | 0.09 |

| Prior ART experience | 1.49 | (1.08, 2.05) | 0.01 | 1.38 | (1.01, 1.90) | 0.05 |

| PI-sparing ART class | 0.72 | (0.51, 1.04) | 0.08 | 0.93 | (0.67, 1.30) | 0.69 |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | 1.58 | (1.15, 2.16) | 0.005 | 1.75 | (1.30, 2.36) | <0.001 |

| Depression diagnosis | 1.32 | (0.96, 1.82) | 0.09 | 1.59 | (1.18, 2.15) | 0.003 |

| Charlson Scoreb 1–2 (ref = 0) | 1.76 | (1.30, 2.38) | <0.001 | 1.48 | (1.10, 1.98) | 0.009 |

| Charlson Scoreb ≥3 (ref = 0) | 4.52 | (2.23, 9.15) | <0.001 | 5.24 | (2.90, 9.45) | <0.001 |

antiretroviral therapy, hazard ratio, men who have sex with men

a Multivariable model includes all parameters listed.

b Modified Charlson comorbidity index which excludes HIV or AIDS-related outcomes.

We observed 521 total deaths: 375 deaths among White patients (25.2/1,000 person-years), 101 deaths among Black patients (27.1/1,000 person-years), and 45 deaths among Hispanic patients (16.4/1,000 person-years). The majority of deaths for all racial/ethnic groups were AIDS-related (Table 3). Hispanic patients had a lower relative frequency of cardiovascular- and cancer-related deaths compared with other racial/ethnic groups.

There was some suggestion (Fig. 1, right panel) that Black patients had the highest and Hispanic patients the lowest risk of death compared with White patients, corresponding to unadjusted HRs of 1.1 (95% CI: 0.9–1.4) and 0.7 (95% CI: 0.5–0.9), respectively. Hispanic patients also had a statistically significant lower risk of death compared with Black patients, with an HR of 0.6 (95% CI: 0.4–0.8). However, the survival benefit for Hispanic patients was no longer observed in multivariable models: the adjusted HRs were 1.2 (95% CI: 0.8–1.7) for Black patients and 0.9 (95% CI: 0.6–1.4) for Hispanic compared with White patients (Table 4), and 0.8 (95% CI: 0.5–1.3) for Hispanic compared with Black patients. Additional adjustment for adherence did not change inferences, with adjusted HRs of 1.4 (95% CI: 1.0, 2.0; = 0.07) and 0.9 (95% CI: 0.5, 1.5) for Black and Hispanic patients, respectively. Similarly, with the additional adjustment for ART adherence, the HR comparing Hispanic and Black patients was 0.6 (95% CI: 0.4, 1.1).

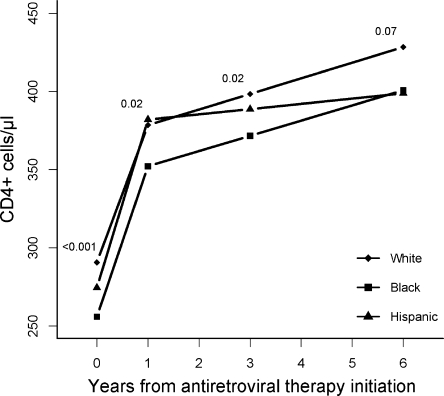

Mean CD4 T-cell counts at baseline were highest among White patients, 291 cells and lower among Hispanic patients, 275 cells, and Black patients, 256 cells (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). By 6 years, CD4 T-cell counts were 30 cells/µL higher in White compared with both Hispanic and Black patients ( = 0.07). However, the rate of change in CD4 T-cell counts was similar by race/ethnicity (data not shown). We observed no differences by race/ethnicity in time to HIV RNA of less than 500 copies/mL, with more than 90% reaching HIV RNA of less than 500 by 24 months in each racial/ethnic group (Fig. 3). Additional adjustments for time-updated CD4 T-cell counts and HIV RNA levels had no effect on the risk of clinical AIDS or death, indicating these did not have a strong intermediate effect (data not shown).

Figure 2.

CD4 T-cell counts by race/ethnicity. Mean CD4 T-cell counts obtained from linear regression models through 6 years after antiretroviral therapy initiation. -values within the figure compare mean CD4 at each time point by race/ethnicity.

Figure 3.

Time to HIV RNA < 500 copies/mL by race/ethnicity. Kaplan-Meier curves presented for time to HIV RNA < 500 copies/mL within 2 years after antiretroviral therapy initiation. Hazard ratios (HR), 95% CIs and -values are also presented.

DISCUSSION

We did not observe a negative disparity with respect to a risk of clinical AIDS or death for racial/ethnic minorities compared with White patients. In fact, Hispanic patients had a statistically significant 34% survival benefit compared with White patients, and a 42% survival benefit compared with Black patients, but no statistically significant differences for racial/ethnic groups were observed after adjustment for demographics, socioeconomic status, and clinical factors. Adherence to antiretrovirals, however, was lower in Hispanic and Black compared with White patients, although this did not influence observed results for clinical outcomes. The absence of racial/ethnic differences in clinical outcomes may be a result of both the comprehensive medical insurance coverage and integrated health care delivery model of KPNC.

Our finding of reduced mortality in HIV-infected Hispanic patients is somewhat surprising given the observed lower adherence rates, reduced immunological responses, and lower census-based socioeconomic status compared with White patients. However, this phenomenon has also been observed for Hispanic persons in the general population without HIV infection who, despite similar socioeconomic status to Black individuals, have clinical outcomes, including cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality similar to or better than White individuals.25,26 This phenomenon has been termed the “Hispanic epidemiological paradox”, with differences in diet, genetics, and extended family support as possible explanatory factors.26 Few prior studies in HIV patients have considered differences in clinical outcomes among Hispanic patients compared with other racial/ethnic groups.4,10,11,13 Of these, 3 reported similar4,10,13 and 1 reported worse11 clinical outcomes for Hispanic compared with White patients. Our study is the first to report significantly reduced mortality for HIV-infected Hispanic patients. Of note, Hispanic patients had particularly low numbers of cardiovascular and cancer-related deaths, consistent with the Hispanic paradox. However, the overall survival benefit was not observed after adjustment for other factors.

Our study is unique in several respects. First, the results are highly generalizable with very similar demographics comparing our patient population to reported HIV/AIDS cases in California.14,27 Second, there is substantially reduced confounding due to unequal access to care because all patients had comprehensive medical coverage. Third, the clinical and administrative databases of KPNC allow for more complete consideration of potential confounding factors, and allow for the investigation of intermediate factors such as CD4 T-cell counts, HIV RNA levels, and ART adherence. Finally, this study is one of the largest to evaluate racial/ethnic differences in clinical outcomes among HIV-infected patients, and included the largest sample to date of Hispanic patients.

To put our study results in context, it is particularly useful to evaluate studies among other populations with access to comprehensive medical coverage, including countries with universal health care,6,9 and the U.S. military,5,8,11,12 which provides free health insurance to current and retired personnel. Several of these indicated no differences in clinical outcomes comparing Black and White HIV-infected populations, including studies in Denmark,6 the United Kingdom,9 and 2 large studies of U.S. military personnel8 and U.S. veterans.5 However, another large study of veterans indicated that Black and Hispanic patients each had a 41% higher age-adjusted risk of death over White patients.11 Finally, a smaller study indicated higher mortality rates for White compared with Black patients among those with Hepatitis C co-infection12. Only 2 studies among U.S. veterans had a larger overall sample size compared with this study, although one only adjusted for age,11 and the other evaluated only mortality after hospitalization.5 These prior studies, however, did not adjust for the potential confounding effects of socioeconomic status and therapy adherence.

Others have compared clinical outcomes by race/ethnicity in settings where equal access to care by race/ethnicity is less certain. One randomized clinical trial10 and 3 cohort studies4,7,13 indicated no association between race/ethnicity and AIDS or death in multivariable models. Unadjusted mortality rates for Black patients were significantly ( < 0.05) higher compared with White patients in 2 of these studies,4,10 thus highlighting the importance of adjustment for confounders on this topic. A small cohort study of HIV-infected persons in New York13 indicated that Hispanic patients had a statistically insignificant lower risk of death compared with White patients, similar in magnitude to unadjusted results presented here. The study by Anastos et al.4 of almost 1,000 women in enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study was the only study on the topic to comprehensibly consider potential confounders including socioeconomic status, therapy adherence, and depression. Our study was thus the largest study to date to provide a comprehensive analysis with respect to consideration of such factors.

Several studies have reported on differences by race/ethnicity with respect to ART adherence, and immunological and virological responses to ART. Most prior studies indicated lower adherence levels among Black patients compared with other racial/ethnic groups,28–32 although 1 study among U.S. veterans indicated no such differences comparing White, Black, and Hispanic patients. Some have found reduced immunological33 or virological34,35 responses for Black compared with White patients, while others have found no differences by race/ethnicity for immunological4,6,34,36,37 or virological4,6,38 outcomes. Our study demonstrated reduced ART adherence levels for Black and Hispanic patients, but similar virological responses to ART by race/ethnicity. However, mean CD4 T-cell counts were significantly lower for Hispanic and Black patients at baseline, a disparity that persisted during follow-up. Nevertheless, these factors did not influence observed associations of race/ethnicity and clinical outcomes when considered as time-dependent factors.

There are limitations to the study. First, therapy adherence was based on prescription refills records and not actual pills consumed. Thus, it is conceivable, although unlikely, that patients did not take medications once filled. However, the misclassification is probably small and not likely to differ by race/ethnicity. Furthermore, an important advantage of this method is that it does not rely on patient recall of pills consumed. An additional limitation is that the results might not be generalizable to HIV-infected patients without medical coverage. However, data indicate members are very similar to the local surrounding and statewide population with respect to age, sex, and race/ethnicity, with only slight underrepresentation of those in lower and higher income and education categories.14,27 We also believe our finding of a lack of racial/ethnic differences in outcome for HIV-infected patients is generalizable to other integrated healthcare systems with comprehensive medical coverage, including other private and public institutions. A further limitation is the potential for residual confounding by socioeconomic status. It is possible that KPNC HIV-infected patients may be economically more advantaged than non-KPNC Black and Hispanic patients14,27; thus census-based measures of socioeconomic status would not fully adjust for such differences.

Our study confirms that in this setting of similar access to integrated care for HIV-infected persons, there is no disparity with respect to clinical outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities. In fact, we observed a lower unadjusted mortality rate for Hispanic patients compared with other racial/ethnic groups, consistent with the Hispanic epidemiological paradox. Confirmation of this finding in other HIV-infected populations is needed. Despite these encouraging results, Black and Hispanic patients had both lower mean adherence rates and lower CD4 T-cell counts compared with White patients. Thus, continued study of outcomes between racial/ethnic groups is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material was presented at the 4th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention, Sydney, Australia, July 22–25, 2007 (#WEPEB107). This research was supported by a Community Benefit grant from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Dr. Silverberg’s contribution was also supported in part by grant number K01AI071725 from the NIAID. We would like to thank Leo Hurley for assistance with data analysis and helpful discussions during manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Footnotes

This material was presented at the 4th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention, Sydney, Australia, July 22–25, 2007 (#WEPEB107). This research was supported by a Community Benefit grant from Kaiser Permanente Northern California and grant number K01AI071725 from the NIAID.

References

- 1.CDC. Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS–33 states, 2001–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:189–93. [PubMed]

- 2.CDC. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005. 2007;17:1–54.

- 3.Heron MP, Smith BL. Deaths: leading causes for 2003. Hyattsville, MD: National vital statistics reports; 2007;15:1–92. [PubMed]

- 4.Anastos K, Schneider MF, Gange SJ, et al. The association of race, sociodemographic, and behavioral characteristics with response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:537–44. [PubMed]

- 5.Giordano TP, Morgan RO, Kramer JR, et al. Is there a race-based disparity in the survival of veterans with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:613–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Jensen-Fangel S, Pedersen L, Pedersen C, et al. The effect of race/ethnicity on the outcome of highly active antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:1541–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Poundstone KE, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Differences in HIV disease progression by injection drug use and by sex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1115–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Silverberg MJ, Wegner SA, Milazzo MJ, et al. Effectiveness of highly-active antiretroviral therapy by race/ethnicity. AIDS. 2006;20:1531–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Smith PR, Sarner L, Murphy M, et al. Ethnicity and discordance in plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load and CD4+ lymphocyte count in a cohort of HIV-1-infected individuals. J Clin Virol. 2003;26:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Tedaldi EM, Absalon J, Thomas AJ, Shlay JC, van den Berg-Wolf M. Ethnicity, race, and gender. Differences in serious adverse events among participants in an antiretroviral initiation trial: results of CPCRA 058 (FIRST Study). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:441–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.McGinnis KA, Fine MJ, Sharma RK, et al. Understanding racial disparities in HIV using data from the veterans aging cohort 3-site study and VA administrative data. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1728–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Merriman NA, Porter SB, Brensinger CM, Reddy KR, Chang KM. Racial difference in mortality among U.S. veterans with HCV/HIV coinfection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:760–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Messeri P, Lee G, Abramson DM, Aidala A, Chiasson MA, Jessop DJ. Antiretroviral therapy and declining AIDS mortality in New York City. Med Care. 2003;41:512–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Gordon NP. How does the adult kaiser permanente membership in Northern California compare with the larger community? Oakland: KP Division of Research; 2009. Available at: http://www-dor.kaiser.org/dor/mhsnet/public/kpnc_community.htm. Accessed June 4, 2009.

- 15.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-Infected adults and adolescents. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2009. [PubMed]

- 16.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Silverberg MJ, Kinsman CJ, Quesenberry CP. Effect of clinical pharmacists on utilization of and clinical response to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:531–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Horberg MA, DeLorenze GN, Klein D, Quesenberry CP Jr. Older age and the response to and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:684–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Steiner JF, Prochazka AV. The assessment of refill compliance using pharmacy records: methods, validity, and applications. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:105–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR. 1992;41:1–19. [PubMed]

- 20.Bendel RB, Afifi AA. Comparison of stopping rules in forward "stepwise" regression. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977;72:46–53. [DOI]

- 21.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression, second edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000.

- 22.Cox DR, Oates D. Analysis of survival data. London and New York: Chapman and Hall; 1984.

- 23.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995.

- 24.Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS–United States, 1981–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jun 2 2006;55:589–92. [PubMed]

- 25.Hayes-Bautista DE, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Schink WO, Hayes-Bautista M. Latino health in California, 1985–1990: implications for family practice. Fam Med. 1994;26:556–62. [PubMed]

- 26.Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep. 1986;101:253–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kleeberger CA, Phair JP, Strathdee SA, Detels R, Kingsley L, Jacobson LP. Determinants of heterogeneous adherence to HIV-antiretroviral therapies in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:82–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kleeberger CA, Buechner J, Palella F, et al. Changes in adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy medications in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS. 2004;18:683–88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Li X, Margolick JB, Conover CS, et al. Interruption and discontinuation of highly active antiretroviral therapy in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:320–28. [PubMed]

- 31.Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, et al. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:756–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Gifford AL, Bormann JE, Shively MJ, Wright BC, Richman DD, Bozzette SA. Predictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:386–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Smith CJ, Sabin CA, Youle MS, et al. Factors influencing increases in CD4 cell counts of HIV-positive persons receiving long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1860–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Hartzell JD, Spooner K, Howard R, Wegner S, Wortmann G. Race and mental health diagnosis are risk factors for highly active antiretroviral therapy failure in a military cohort despite equal access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:411–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Schackman BR, Ribaudo HJ, Krambrink A, Hughes V, Kuritzkes DR, Gulick RM. Racial differences in virologic failure associated with adherence and quality of life on efavirenz-containing regimens for initial HIV therapy: results of ACTG A5095. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:547–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Kumar PN, Rodriguez-French A, Thompson MA, et al. A prospective, 96-week study of the impact of Trizivir, Combivir/nelfinavir, and lamivudine/stavudine/nelfinavir on lipids, metabolic parameters and efficacy in antiretroviral-naive patients: effect of sex and ethnicity. HIV Med. 2006;7:85–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Giordano TP, Wright JA, Hasan MQ, White AC Jr., Graviss EA, Visnegarwala F. Do sex and race/ethnicity influence CD4 cell response in patients who achieve virologic suppression during antiretroviral therapy? Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:433–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Lucas GM, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in a large urban clinic: risk factors for virologic failure and adverse drug reactions. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:81–7. [DOI] [PubMed]