Abstract

Objective To study the inter-observer variation related to extraction of continuous and numerical rating scale data from trial reports for use in meta-analyses.

Design Observer agreement study.

Data sources A random sample of 10 Cochrane reviews that presented a result as a standardised mean difference (SMD), the protocols for the reviews and the trial reports (n=45) were retrieved.

Data extraction Five experienced methodologists and five PhD students independently extracted data from the trial reports for calculation of the first SMD result in each review. The observers did not have access to the reviews but to the protocols, where the relevant outcome was highlighted. The agreement was analysed at both trial and meta-analysis level, pairing the observers in all possible ways (45 pairs, yielding 2025 pairs of trials and 450 pairs of meta-analyses). Agreement was defined as SMDs that differed less than 0.1 in their point estimates or confidence intervals.

Results The agreement was 53% at trial level and 31% at meta-analysis level. Including all pairs, the median disagreement was SMD=0.22 (interquartile range 0.07-0.61). The experts agreed somewhat more than the PhD students at trial level (61% v 46%), but not at meta-analysis level. Important reasons for disagreement were differences in selection of time points, scales, control groups, and type of calculations; whether to include a trial in the meta-analysis; and data extraction errors made by the observers. In 14 out of the 100 SMDs calculated at the meta-analysis level, individual observers reached different conclusions than the originally published review.

Conclusions Disagreements were common and often larger than the effect of commonly used treatments. Meta-analyses using SMDs are prone to observer variation and should be interpreted with caution. The reliability of meta-analyses might be improved by having more detailed review protocols, more than one observer, and statistical expertise.

Introduction

Systematic reviews of clinical trials, with meta-analyses if possible, are regarded as the most reliable resource for decisions about prevention and treatment. They should be based on a detailed protocol that aims to reduce bias by pre-specifying methods and selection of studies and data.1 However, as meta-analyses are usually based on data that have already been processed, interpreted, and summarised by other researchers, data extraction can be complicated and can lead to important errors.2

There is often a multiplicity of data in trial reports that makes it difficult to decide which ones to use in a meta-analysis. Furthermore, data are often incompletely reported,2 3 which makes it necessary to perform calculations or impute missing data, such as missing standard deviations. Different observers may get different results, but previous studies on observer variation have not been informative, because of few observers, few trials, or few data.4 5 We report here a detailed study of observer variation that explores the sources of disagreement when extracting data for calculation of standardised mean differences.

Methods

Using a computer generated list of random numbers, we selected a random sample of 10 recent Cochrane reviews published in the Cochrane Library in issues 3 or 4 in 2006 or in issues 1 or 2 in 2007. We also retrieved the reports of the randomised trials that were included in the reviews and the protocols for each of the reviews. Only Cochrane reviews were eligible, as they are required to have a pre-specified published protocol.

We included reviews that reported at least one result as a standardised mean difference (SMD). The SMD is used when trial authors have used different scales for measuring the same underlying outcome—for example, pain can be measured on a visual analogue scale or on a 10-point numeric rating scale. In such cases, it is necessary to standardise the measurements on a uniform scale before they can be pooled in a meta-analysis. This is typically achieved by calculating the SMD for each trial, which is the difference in means between the two groups, divided by the pooled standard deviation of the measurements.1 By this transformation, the outcome becomes dimensionless and the scales become comparable, as the results are expressed in standard deviation units.

The first SMD result in each review that was not based on a subgroup result was selected as our index result. The index result had to be based on two to 10 trials and on published data only (that is, there was no indication that the review authors had received additional outcome data from the trial authors).

Five methodologists with substantial experience in meta-analysis and five PhD students independently extracted the necessary data from the trial reports for calculation of the SMDs. The observers had access to the review protocols but not to the completed Cochrane reviews and the SMD results. An additional researcher (BT) highlighted the relevant outcome in the protocols, along with other important issues such as pre-specified time points of interest, which intervention was the experimental one, and which was the control. If information was missing regarding any of these issues, the observers decided by themselves what to select from the trial reports. The observers received the review protocols, trial reports, and a copy of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews6 as PDF files.

The data extraction was performed during one week when the 10 observers worked independently at the same location in separate rooms. The observers were not allowed to discuss the data extraction. If the data were available, the observers extracted means, standard deviations, and number of patients for each group; otherwise, they could calculate or impute the missing data, such as from an exact P value. The observers also interpreted the sign of the SMD results—that is, whether a negative or a positive result indicated superiority of the experimental intervention. If the observers were uncertain, the additional researcher retrieved the paper that originally described the scale, and the direction of the scale was based on this information. All calculations were documented, and the observers provided information about any choices they made regarding multiple outcomes, time points, and data sources in the trial reports. During the week of data extraction the issue of whether the observers could exclude trials emerged, as there were instances where the observers were unable to locate any relevant data in the trial reports or felt that the trial did not meet the inclusion criteria in the Cochrane protocol. It was decided that observers could exclude trials, and the reasons for exclusion were documented.

Based on the extracted data, the additional researcher calculated trial and meta-analysis SMDs for each observer using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2. To allow comparison with the originally published meta-analyses, the same method (random effects or fixed effect model) was used as that in the published meta-analysis. In cases where the observers had extracted two sets of data from the same trial—for example, because there were two control groups—the data were combined so that only a single SMD resulted from each trial.1

Agreement between pairs of observers was assessed at both meta-analysis and trial level, pairing the 10 observers in all possible ways (45 pairs). This provides an indication of the likely agreement that might be expected in practice, since two independent observers are recommended when extracting data from papers for a systematic review.1 2 5 6 Agreement was defined as SMDs that differed less than 0.1 in their point estimates and in their confidence intervals. The cut point of 0.1 was chosen because many commonly used treatments have an effect of 0.1 to 0.5 compared with placebo2; furthermore, an error of 0.1 can be important when two active treatments have been compared, for there is usually little difference between active treatments. Confidence intervals were not calculated, as the data from the pairings were not independent.

To determine the variation in meta-analysis results that could be obtained from the multiplicity of different SMD estimates across observers, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation for each meta-analysis. In each iteration of the simulation, we randomly sampled one observer for each trial and entered his or her SMD (and standard error) for that trial into a meta-analysis. Thus each sampled meta-analysis contained SMD estimates from different observers. If the sampled observer excluded the trial from his or her meta-analysis, the simulated meta-analysis also excluded that trial. We examined the distribution of meta-analytic SMD estimates across 10 000 simulations.

Results

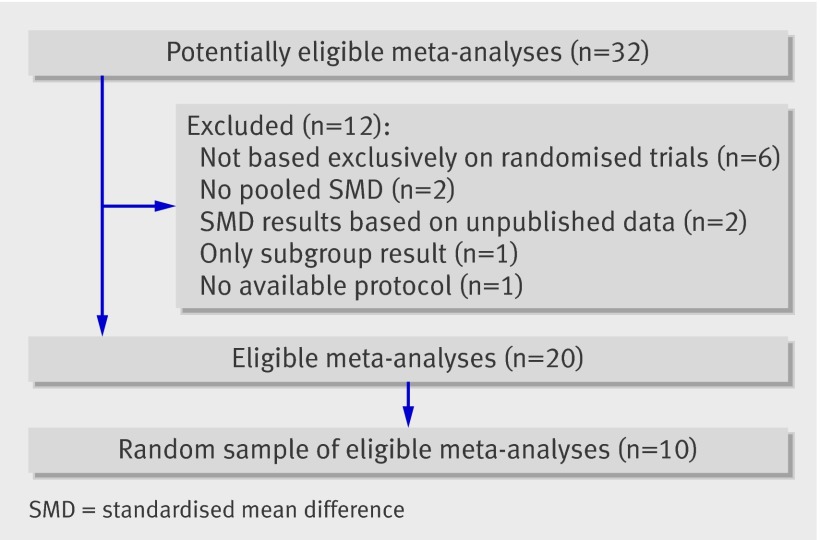

The flowchart for inclusion of meta-analyses is shown in figure 1. Out of 32 potentially eligible meta-analyses, the final sample consisted of 10.7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The 10 meta-analyses comprised 45 trials, which yielded 450 pairs of observers at the meta-analysis level and 2025 pairs at the trial level.

Fig 1 Flowchart for selection of meta-analyses

The level of information in the review protocols is given in table 1. None of the review protocols contained information on which scales should be preferred. Three protocols gave information about which time point to select and four mentioned whether change from baseline or values after treatment should be preferred. Nine described which type of control group to select, but none reported any hierarchy among similar control groups or any intentions to combine such groups.

Table 1.

Level of information provided in the 10 meta-analysis protocols used in this study for data extraction

| Information | Meta-analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gava et al7 | Woodford et al8 | Martinez et al9 | Orlando et al10 | Buckley et al11 | Ipser et al12 | Mistiaen et al13 | Afolabi et al14 | Uman et al15 | Moore et al16 | |

| Possible control group(s) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Hierarchy of control groups | √* | √* | ||||||||

| Which time point to select | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Whether to use change from baseline or values after treatment | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Hierarchy of measuring methods or scales | ||||||||||

*Only one possible control group stated

The outcomes analysed in the 10 meta-analyses were diverse: in six, the outcome was a clinician reported score (three symptom scores, one general functioning score, one hepatic density score, and one neonatal score); in one, it was objective (range of movement in ankle joints); and in three, it was self reported (pain, tinnitus, and patient knowledge).

Agreement at trial level

In table 2 the different levels of agreement are shown. Across trials, the agreement was 53% for the 2025 pairs (61% for the 450 pairs of methodologists, 46% for the 450 pairs of PhD students, and 52% for the 1125 mixed pairs). The agreement rates for the individual trials ranged from 4% to 100%. Agreement between all observers was found for four of the 45 trials.

Table 2.

Levels of overall agreement between observer pairs in the calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs)* from 10 meta-analyses (which comprised a total of 45 trials)

| Observer pairs | No (%) of pairs in agreement |

|---|---|

| Trial level | |

| All pairs (n=2025): | 1068 (53) |

| Methodologists (n=450) | 273 (61) |

| PhD students (n=450) | 209 (46) |

| Mixed pairs (n=1125) | 586 (52) |

| Meta-analysis level | |

| All pairs (n=450): | 138 (31) |

| Methodologists (n=100) | 33 (33) |

| PhD students (n=100) | 27 (27) |

| Mixed pairs (n=250) | 78 (31) |

*Agreement defined as SMDs that differed less than 0.1 in their point estimates and in their 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3 presents the reasons for disagreement, which fell into three broad categories: different choices, exclusion of a trial, and data extraction errors. The different choices mainly concerned cases with multiple groups to choose from when selecting the experimental or the control groups (15 trials), which time point to select (nine trials), which scale to use (six trials), and different ways of calculating or imputing missing numbers (six trials). The most common reasons for deciding to exclude a trial was that the trial did not meet the inclusion criteria described in the protocol for the review (14 trials) and that the reporting was so unclear that data extraction was not possible (14 trials). Data extraction errors were less common but involved misinterpretation of the direction of the effect in four trials.

Table 3.

Reasons for disagreement among the 41 trials on which the observer pairs disagreed in the calculated standardised mean differences

| Reason for disagreement | No of trials* |

|---|---|

| Different choices regarding: | |

| Groups, pooling, splitting | 15 |

| Timing | 9 |

| Scales | 6 |

| Different calculations or imputations | 6 |

| Dropouts | 4 |

| Use of change from baseline or values after treatment | 4 |

| Individual patient data | 1 |

| Exclusion of trials because: | |

| Did not meet protocol inclusion criteria | 14 |

| Reporting unclear | 14 |

| Missing data | 7 |

| Could not or would not calculate | 2 |

| Only change from baseline or only values after treatment | 2 |

| Errors due to: | |

| Misreading or typing error | 4 |

| Direction of effect | 4 |

| Standard error taken as standard deviation | 2 |

| Rounding | 1 |

| Calculation error | 1 |

*There may be more than one reason for disagreement per trial.

The importance of which standard deviation to use was underpinned in a trial that did not report standard deviations.17 The only reported data on variability were F test values and P values from a repeated measure, analysis of variance, performed on changes from baseline. The five PhD students excluded the trial because of the missing data, whereas the five experienced methodologists imputed five different standard deviations. One used a standard deviation from the report originally describing the scale, another used the average standard deviation reported in the other trials in the meta-analysis, and the other three observers calculated standard deviations based on the reported data, using three different methods. In addition, one observer selected a different time point from the others. The different standard deviations resulted in different trial SMDs ranging from −1.82 to 0.34 in their point estimates.

Agreement at meta-analysis level

Across the meta-analyses, the agreement was 31% for the 450 pairs (33% for the 100 pairs of methodologists, 27% for the 100 pairs of PhD students, and 31% for the 250 mixed pairs) (table 2). The agreement rates for the individual meta-analyses ranged from 11% to 80% (table 4). Agreement between all observers was not found for any of the 10 meta-analyses.

Table 4.

Levels of agreement at the meta-analysis level between observer pairs in the calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) from 10 meta-analyses*

| Meta-analysis | No (%) of pairs in agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pairs (n=45) | Methodologist (n=10) | Students (n=10) | Mixed pairs (n=25) | |

| Gava et al7 | 6 (13) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 5 (20) |

| Woodford et al8 | 11 (24) | 2 (20) | 1 (10) | 8 (32) |

| Martinez et al9 | 7 (16) | 3 (30) | 1 (10) | 3 (12) |

| Orlando et al10 | 5 (11) | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | 2 (8) |

| Buckley et al11 | 6 (13) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 4 (16) |

| Ipser et al12 | 13 (29) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | 7 (28) |

| Mistiaen et al13 | 16 (36) | 6 (60) | 2 (20) | 8 (32) |

| Afolabi et al14 | 28 (62) | 6 (60) | 6 (60) | 16 (64) |

| Uman et al15 | 36 (80) | 6 (60) | 10 (100) | 20 (80) |

| Moore et al16 | 10 (22) | 3 (30) | 2 (20) | 5 (20) |

*Agreement defined as SMDs that differed less than 0.1 in their point estimates and in their 95% confidence intervals.

The distribution of the disagreements is shown in figure 2. Ten per cent agreed completely, 21% had a disagreement below our cut point of 0.1, 38% had a disagreement between 0.1 and 0.49, and 28% disagreed by at least 0.50 (including 10% that had disagreements of ≥1). The last 18 pairs (4%) were not quantifiable since one observer excluded all the trials from two meta-analyses. The median disagreement was SMD=0.22 for the 432 quantifiable pairs with an interquartile range from 0.07 to 0.61. There were no differences between the methodologists and the PhD students (table 2).

Fig 2 Sizes of the disagreements between observer pairs in the calculated standardised mean differences (SMDs) from 10 meta-analyses. Comparisons are at the meta-analysis level. (*All the underlying trials were excluded)

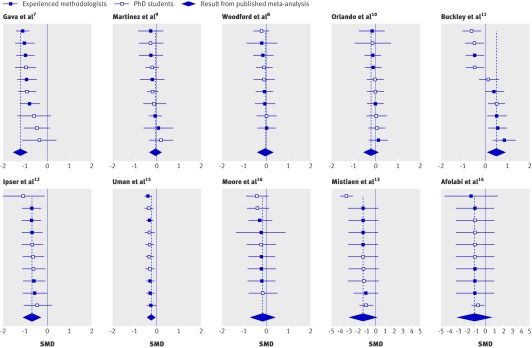

Figure 3 shows the SMDs calculated by each of the 10 observers for the 10 meta-analyses, and the results from the originally published meta-analyses. Out of the total of 100 calculated SMDs, seven values corresponding to significant results in the originally published meta-analyses were now non-significant, three values corresponding to non-significant results were now significant, and four values, which were related to the same published meta-analysis, showed a significantly beneficial effect for the control group whereas the original publication reported a significantly beneficial effect for the experimental group.11 The SMDs for this meta-analysis had particularly large disagreements, partly because only two trials were included, leaving less possibility for the pooled result to average out. The reasons for the large disagreements were diverse and included selection of different time points, control groups, intervention groups, measurement scales, and whether to exclude one of the trials.

Fig 3 Forest plots of standardised mean differences (SMDs) and 95% confidence intervals calculated from data from each of the 10 observers for the 10 meta-analyses

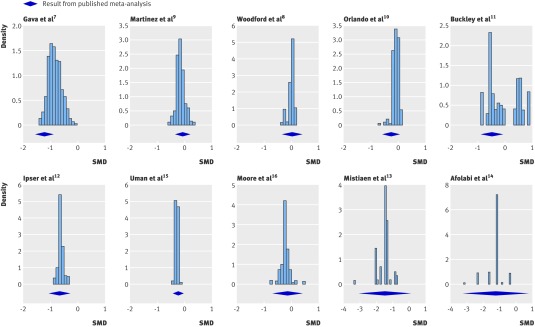

The results of the Monte Carlo investigation are presented in figure 4. For four of the 10 meta-analyses7 11 13 14 there was considerable variation in the potential SMDs, allowing for differences in SMDs of up to 3. In two of these, around half of the distribution extended beyond even the confidence interval for the published result of the meta-analysis.7 11 The other meta-analyses had three and two trials respectively, and the distributions reflect the wide scatter of SMDs from these trials.

Fig 4 Histograms of standardised mean differences (SMD) estimated in the Monte Carlo simulations for each of 10 meta-analyses

Discussion

We found that disagreements between observers were common and often large. Ten per cent of the disagreements at the meta-analysis level amounted to an SMD of at least 1, which is far greater than the effect of most of the treatments we use compared with no treatment. As an example, the effect of inhaled corticosteroids on asthma symptoms, which is generally regarded as substantial, is 0.49.18 Important reasons for disagreement were differences in selection of time points, scales, control groups, and type of calculations, whether to include a trial in the meta-analysis, and finally data extraction errors made by the observers.

The disagreement depended on the reporting of data in the trial reports and on how much room was left for decision in the review protocols. One of the reviews exemplified the variation arising from a high degree of multiplicity in the trial reports combined with a review protocol leaving much room for choice.11 In the review protocol, the time point was described as “long term (more than 26 weeks),” but in the two trials included in the meta-analysis there were several options. For one trial,19 there were two: end of treatment (which lasted 9 months) or three month follow-up. For the other,20 21 22 there were three: 6, 12, and 18 month follow-up (treatment lasted 3 weeks). The observers used all the different time points, and all had a plausible reason for their choice: in concordance with the time point used in the other trial, the maximum period of observation, and the least drop out of patients.

Strengths and weaknesses

The primary strength of our study is that we took a broad approach and showed that there are other important sources of variation in meta-analysis results than simple errors. Furthermore, we included a considerable number of experienced as well as inexperienced observers and a large number of trials to elucidate the sources of variation and their magnitude. Finally, the study setup ensured independent observations according to the blueprint laid out in the review protocols and likely mirrored the independent data extraction that ideally should happen in practice.

The experimental setting also had limitations. Single data extraction produces more errors than double data extraction.5 In real life, some of the errors we made would therefore probably have been detected before the data were used for meta-analyses, as it is recommended for Cochrane reviews that there should be at least two independent observers and that any disagreement should be resolved by discussion and, if necessary, arbitration by a third person.1 We did not perform a consensus step, as the purpose of our study was to explore how much variation would occur when data extraction was performed by different observers. However, given the amount of multiplicity in the trial reports and the uncertainties in the protocols, it is likely that even pairs of observers would disagree considerably with other pairs.

Other limitations were that the observers were under time pressure, although only one person needed more time, as he fell ill during the assigned week. The observers were presented with protocols they had not developed themselves, based on research questions they had not asked, and in disease areas where they were mostly not experts. Another limitation is that, even though one of the exclusion criteria was that the authors of the Cochrane review had not obtained unpublished data from the trial authors, it became apparent during data extraction that some of the trial reports did not contain the data needed for the calculation of an SMD. It would therefore have been helpful to contact trial authors.

Other similar research

The SMD is intended to give clinicians and policymakers the most reliable summary of the available trial evidence when the outcomes have been measured on different continuous or numeric rating scales. Surprisingly, the method has not previously been examined in any detail for its own reliability. Previous research has been sparse and has focused on errors in data extraction.2 4 5 In one study, the authors found errors in 20 of 34 Cochrane reviews, but, as they gave no numerical data, it is not possible to judge how often these were important.4 In a previous study of 27 meta-analyses, of which 16 were Cochrane reviews,2 we could not replicate the SMD result for at least one of the two trials we selected for checking from each meta-analysis within our cut point of 0.1 in 10 of the meta-analyses. When we tried to replicate these 10 meta-analyses, including all the trials, we found that seven of them were erroneous; one was subsequently retracted, and in two a significant difference disappeared or appeared.2 The present study adds to the previous research by also highlighting the importance of different choices when selecting outcomes for meta-analysis. The results of our study apply more broadly than to meta-analyses using the SMD, as many of the reasons for disagreement were not related to the SMD method but would be important also when analysing data using the weighted mean difference method, which is the method of choice when the outcome data have been measured on the same scale.

Conclusions

Disagreements were common and often larger than the effect of commonly used treatments. Meta-analyses using SMDs are prone to observer variation and should be interpreted with caution. The reliability of meta-analyses might be improved by having more detailed review protocols, more than one observer, and statistical expertise.

Review protocols should be more detailed and made permanently available, also after the review is published, to allow other researchers to check that the review was done according to the protocol. In February 2008, the Cochrane Collaboration updated its guidelines and recommended that researchers in their protocols list possible ways of measuring the outcomes—such as using different scales or time points—and specify which ones to use. Our study provides strong support for such precautions. Reports of meta-analyses should also follow published guidelines1 23 to allow for sufficient critical appraisal. Finally the reporting of trials needs to be improved, according to the recommendations in the CONSORT statement,24 reducing the need for calculations and imputation of missing data.

What is already known on this topic

Incorrect data extraction in meta-analyses can lead to false results

Multiplicity in trial reports invites variation in data extraction, as different judgments will lead to different choices about which data to extract

The impact of these different errors and choices on meta-analysis results is not clear

What this study adds

There is considerable observer variation in data extraction and decisions on which trials to include

The reasons for disagreement are different choices and errors

The impact on meta-analyses is potentially large

Contributors: All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: BT, PCG, JPTH, PJ. Acquisition of data: all authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: BT, PCG, JPTH, PJ, EN. Drafting of the manuscript: BT. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: BT, PCG, JPTH, EN. Administrative, technical, or material support: BT, PCG. Study guarantor: PCG.

Funding: This study is part of a PhD funded by IMK Charitable Fund and the Nordic Cochrane Centre. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The researchers were independent from the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b3128

References

- 1.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.0.0. 2008. www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 2.Gotzsche PC, Hrobjartsson A, Maric K, Tendal B. Data extraction errors in meta-analyses that use standardized mean differences. JAMA 2007;298:430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan AW, Hrobjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291:2457-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones AP, Remmington T, Williamson PR, Ashby D, Smyth RL. High prevalence but low impact of data extraction and reporting errors were found in Cochrane systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buscemi N, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Tjosvold L, Klassen TP. Single data extraction generated more errors than double data extraction in systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:697-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 4.2.6. 2006. www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 7.Gava I, Barbui C, Aguglia E, Carlino D, Churchill R, De VM, et al. Psychological treatments versus treatment as usual for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodford H, Price C. EMG biofeedback for the recovery of motor function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD004585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez DP, Waddell A, Perera R, Theodoulou M. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD005233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlando R, Azzalini L, Orando S, Lirussi F. Bile acids for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and/or steatohepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD005160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckley LA, Pettit T, Adams CE. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD004716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ipser JC, Carey P, Dhansay Y, Fakier N, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy augmentation strategies in treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD005473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afolabi BB, Lesi FE, Merah NA. Regional versus general anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD004350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Kisely S. Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD005179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore M, Little P. Humidified air inhalation for treating croup. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD002870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones MK, Menzies RG. Danger ideation reduction therapy (DIRT) for obsessive-compulsive washers. A controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 1998;36:959-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams NP, Bestall JC, Lasserson TJ, Jones PW, Cates C. Fluticasone versus placebo for chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD003135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durham RC, Guthrie M, Morton RV, Reid DA, Treliving LR, Fowler D, et al. Tayside-Fife clinical trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for medication-resistant psychotic symptoms. Results to 3-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:303-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemp R, Kirov G, Everitt B, Hayward P, David A. Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy. 18-month follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Healey A, Knapp M, Astin J, Beecham J, Kemp R, Kirov G, et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of compliance therapy for people with psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, Everitt B, David A. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1996;312:345-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials 2001. Explore (NY) 2005;1(1):40-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]