Abstract

Objective To assess the risk of venous thrombosis in current users of different types of hormonal contraception, focusing on regimen, oestrogen dose, type of progestogen, and route of administration.

Design National cohort study.

Setting Denmark, 1995-2005.

Participants Danish women aged 15-49 with no history of cardiovascular or malignant disease.

Main outcome measures Adjusted rate ratios for all first time deep venous thrombosis, portal thrombosis, thrombosis of caval vein, thrombosis of renal vein, unspecified deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism during the study period.

Results 10.4 million woman years were recorded, 3.3 million woman years in receipt of oral contraceptives. In total, 4213 venous thrombotic events were observed, 2045 in current users of oral contraceptives. The overall absolute risk of venous thrombosis per 10 000 woman years in non-users of oral contraceptives was 3.01 and in current users was 6.29. Compared with non-users of combined oral contraceptives the rate ratio of venous thrombembolism in current users decreased with duration of use (<1 year 4.17, 95% confidence interval 3.73 to 4.66, 1-4 years 2.98, 2.73 to 3.26, and >4 years 2.76, 2.53 to 3.02; P<0.001) and with decreasing dose of oestrogen. Compared with oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel and with the same dose of oestrogen and length of use, the rate ratio for oral contraceptives with norethisterone was 0.98 (0.71 to 1.37), with norgestimate 1.19 (0.96 to 1.47), with desogestrel 1.82 (1.49 to 2.22), with gestodene 1.86 (1.59 to 2.18), with drospirenone 1.64 (1.27 to 2.10), and with cyproterone 1.88 (1.47 to 2.42). Compared with non-users of oral contraceptives, the rate ratio for venous thromboembolism in users of progestogen only oral contraceptives with levonorgestrel or norethisterone was 0.59 (0.33 to 1.03) or with 75 μg desogestrel was 1.12 (0.36 to 3.49), and for hormone releasing intrauterine devices was 0.90 (0.64 to 1.26).

Conclusion The risk of venous thrombosis in current users of combined oral contraceptives decreases with duration of use and decreasing oestrogen dose. For the same dose of oestrogen and the same length of use, oral contraceptives with desogestrel, gestodene, or drospirenone were associated with a significantly higher risk of venous thrombosis than oral contraceptives with levonorgestrel. Progestogen only pills and hormone releasing intrauterine devices were not associated with any increased risk of venous thrombosis.

Introduction

Studies have shown an increased risk of venous thrombosis with use of combined oral contraceptives.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 These studies have generally found a higher risk during the first year of use and with oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene rather than levonorgestrel.1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 12

With the shift from combined pills containing 50 μg ethinylestradiol (oestrogen) to low dose pills containing 30-40 μg, a decrease in the risk of venous thrombosis would be expected. Results have, however, been conflicting,12 15 and evidence of a further decrease in risk associated with a reduction to 20 μg oestrogen is lacking.12 In addition, evidence is sparse on the risk of venous thromboembolism with oral contraceptives containing the new progestogen drospirenone, progestogen only pills with 75 µg desogestrel, and hormone releasing intrauterine devices.

We assessed the risk of venous thromboembolism in current users of different types of hormonal contraception, focusing on duration of use, regimen (combined oral contraceptives versus progestogen only pills), and the effect of oestrogen dose, type of progestogen, and route of administration.

Methods

This study was designed as a cohort study, with linkage between four national Danish registries for prescriptions, education, and health. The National Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics has recorded all redeemed prescriptions on Danish citizens since 1994 according to specific Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes and the amount of drugs prescribed, in defined daily doses. Since 1977 the National Registry of Patients has collected discharge diagnoses and surgical codes from all Danish hospitals. This registry also includes births and abortions. Diagnoses are classified according to the international classification of diseases; before 1994 using the eighth revision and thereafter the 10th revision. Statistics of Denmark include updated information about length of schooling and any ongoing or completed education of all Danish citizens. The Central Person Registry includes a 10 digit personal identification number of all Danish citizens, given at birth or immigration, and information on address and vital status that is updated daily. The personal identification number is a unique personal identifier recorded in all public registries, thus allowing linkage between these registries.

Study population

Danish women aged 15-49 from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2005 were identified in the Central Person Registry.

In the National Registry of Patients we identified women (n=14 749) with malignant disease (ICD 8 codes 153, 154, 183, 184, and 200-206, or ICD 10 codes DC81-85, DC88, and DC90-96) and those (n=20 128) with a cardiovascular event (ICD 8 codes 430, 431, 433, 434, 436, 450, 451.00/08/99, 452, and 453.02, or ICD 10 codes DI21-26, DI60-64, and DI80-82) before the study period (1977-94). These 34 877 women were excluded because of their increased risk for venous thrombosis, decreased probability of being users of combined oral contraceptives, and because we aimed to assess the risk for a first ever thrombotic event. New cases of cancer or cardiovascular diseases during the study period were censored at the date of diagnosis. Women who emigrated were censored at the time they left the country.

From the abortion and birth registry we identified women who were pregnant during the study period, by identifying those who had delivered (DO600-DO849) and those who had a miscarriage (DO021 and DO03), induced abortion (DO040-DO059), or ectopic pregnancy (DO000-DO009). Algorithms for the length of pregnancy in each case were generated from the record of the gestational age, and these women were excluded from the study during pregnancy and 12 weeks after delivery or four weeks after an abortion or ectopic pregnancy. Thus 805 464 women were excluded from the study population for a period of 460 465 pregnancy years. The study population therefore comprised all non-pregnant women with no previous cancer or cardiovascular diseases.

End points

Our end points were first time deep venous thrombosis (ICD 10 codes DI801, DI802, and DI803), portal thrombosis (DI81), thrombosis of caval vein (DI822), thrombosis of renal vein (DI823), unspecified deep vein thrombosis (DI828 and DI829), and pulmonary embolism (DI26) during the study period.

We have previously validated diagnoses of venous thromboembolism in the National Registry of Patients (1994-8) and found about 10% uncertain.12 In the remaining included women with diagnoses, 97% had been examined by venography or ultrasonography and 94% had received anticoagulation therapy. Of the 3% who were not examined by venography or ultrasonography, 2% received anticoagulation therapy. Thus the diagnosis was uncertain in less than 1% of participants.

Data on use of hormonal contraception

From the National Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics we obtained data on use of hormonal contraceptives among Danish women aged 15-49 during the study period.

Current use of hormonal contraception was defined as having a valid prescription at time of admission to hospital according to prescribed defined daily doses. Previous use was defined as any previous recorded use during the study period, and never use as no recorded prescription for hormonal contraception during the study period. Length of use was defined as the sum of valid prescriptions, with periods of non-use subtracted if they occurred between periods of use.

Hormone releasing intrauterine devices were assumed to be used for an average of three years, unless a new device was prescribed within a six year period from the latest prescription. In that case the woman was assumed to have had an intrauterine device without interruption. If oral contraception was prescribed before the three years expired, the device was considered to have been removed at the time the oral contraceptive was prescribed.

Hormonal contraception was categorised according to time of usage (current, previous, or never), regimen (combined oral contraceptives, progestogen only pills, or hormone releasing intrauterine device), oestrogen dose (50 μg, 30-40 μg, or 20 μg), type of progestogen (norethisterone, levonorgestrel, norgestimate, desogestrel, gestodene, drospirenone, or cyproterone), and length of use of combined oral contraceptives in current users (<1 year, 1-4 years, or >4 years). Progestogen only pills were subdivided into those containing 30 µg levonorgestrel or 350 µg norethisterone and those containing 75 µg desogestrel.

We chose non-users of oral contraceptives (never users plus former users) as our reference group because never users are an increasingly selected group of women, and some who were categorised as never users in our study window might have used oral contraceptives before 1995.

Confounders

From the National Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics we also obtained information on redeemed drugs for diabetes (ATC A10), heart disease (ATC C01), antihypertension (ATC C02), diuresis (ATC C03), β blockade (ATC C07), calcium antagonism (ATC C08), the renin-angiotensin system (ATC C09), and serum lipid lowering (ATC C10).

Information about schooling and education was provided by Statistics Denmark. Educational level was categorised into four groups: primary school only, secondary school only, any school with three or four years of further education, and secondary school with five or six years of further education.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Poisson regression. The data consisted of time at risk (woman years) and number of venous thrombotic events for each combination of hormonal contraception, length of use, age band, and educational level. Age was used as the timescale in analyses and divided into five year bands, assuming a linear trend in risk of venous thromboembolism within each band. Confounders were retained in the multivariate analysis if they changed the estimates by more than 5%.

Absolute crude risk estimates and adjusted rate ratios, with 95% confidence intervals, were calculated for specific combinations of oestrogen dose, progestogen type, and length of use. In addition we calculated the influence of specific types of progestogen after adjustment for length of use.

Results

The analysis included 3.4 million woman years of current use, 2.3 million woman years of former use, 4.8 million woman years of never use, or a total of 10.4 million woman years of observation (table 1). A total of 4213 first time venous thrombotic events were recorded during the study period and of these 2045 were among current users of hormonal contraception. The venous thrombotic events included deep vein leg thrombosis (61.8%), pulmonary embolism (26.2%), femoral vein thrombosis (4.7%), portal thrombosis (1.2%), caval or renal thrombosis (0.8%), and unspecified deep vein thrombosis (5.4%).

Table 1.

Crude incidence rates and adjusted rate ratios of venous thrombosis in women using different types of hormonal contraception

| Characteristics | Woman years | % of woman years | No of women with venous thrombosis | Rate per 10 000 woman years | Adjusted rate ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||||

| 15-19 | 1 359 821 | 13.0 | 250 | 1.84 | 0.39 (0.33 to 0.45)* |

| 20-24 | 1 491 764 | 14.3 | 444 | 2.98 | 0.62 (0.54 to 0.70)* |

| 25-29 | 1 491 959 | 14.3 | 537 | 3.60 | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.96)* |

| 30-34 | 1 587 896 | 15.2 | 598 | 3.77 | Reference |

| 35-39 | 1 628 852 | 15.6 | 685 | 4.21 | 1.18 (1.05 to 1.32)* |

| 40-44 | 1 518 172 | 14.5 | 797 | 5.25 | 1.57 (1.41 to 1.74)* |

| 45-49 | 1 368 909 | 13.1 | 902 | 6.59 | 2.09 (1.88 to 2.32)* |

| Total | 10 447 373 | 100.0 | 4213 | 4.03 | — |

| Previous use | |||||

| Never | 4 813 053 | 46.1 | 1467 | 3.05 | Reference |

| Former | 2 278 576 | 21.8 | 667 | 2.93 | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.18)† |

| Current use | |||||

| Non-use (never or former use of oral contraceptives) | 7 194 242 | 67.9 | 2168 | 3.01 | Reference |

| Current use of oral contraceptives | 3 253 131 | 31.1 | 2045 | 6.29 | 2.83 (2.65 to 3.01)† |

| Use of combined pill: | |||||

| <1 year | 684 061 | 21.6 | 443 | 6.48 | 4.17 (3.73 to 4.66)† |

| 1-4 years | 1 449 000 | 45.8 | 787 | 5.43 | 2.98 (2.73 to 3.26)† |

| >4 years | 1 031 953 | 32.6 | 793 | 7.68 | 2.76 (2.53 to 3.02)† |

| Oral contraceptives with 50 μg oestrogen | 82 902 | 2.5 | 65 | 7.84 | 2.67 (2.09 to 3.42)† |

| Oral contraceptives with 20-40 μg oestrogen and: | |||||

| Levonorgestrel | 367 408 | 10.9 | 201 | 5.47 | 2.02 (1.75 to 2.34)† |

| Desogestrel or gestodene | 2 008 262 | 59.8 | 1370 | 6.82 | 3.55 (3.30 to 3.83)† |

| Drospirenone | 131 541 | 3.9 | 103 | 7.83 | 4.00 (3.26 to 4.91)† |

| Progestogen only: | |||||

| Levonorgestrel 30 μg or norethisterone 350 μg | 65 820 | 0.6 | 12 | 1.82 | 0.59 (0.33 to 1.04)† |

| Desogestrel 75 μg | 9044 | 0.1 | 3 | 3.32 | 1.10 (0.35 to 3.41)† |

| Hormone releasing intrauterine device | 101 351 | 1.0 | 34 | 3.35 | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.26) |

*Adjusted for current use of oral contraceptives, calendar year, and educational level.

†Adjusted for age, calendar year, and educational level.

Drugs against diabetes, heart diseases, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia influenced the risk estimates of oral contraceptives by less than 5%, and were consequently excluded. Age, calendar year, and education were all significant confounders and were included in the analysis. There was no interaction between age and the calculated rate ratios.

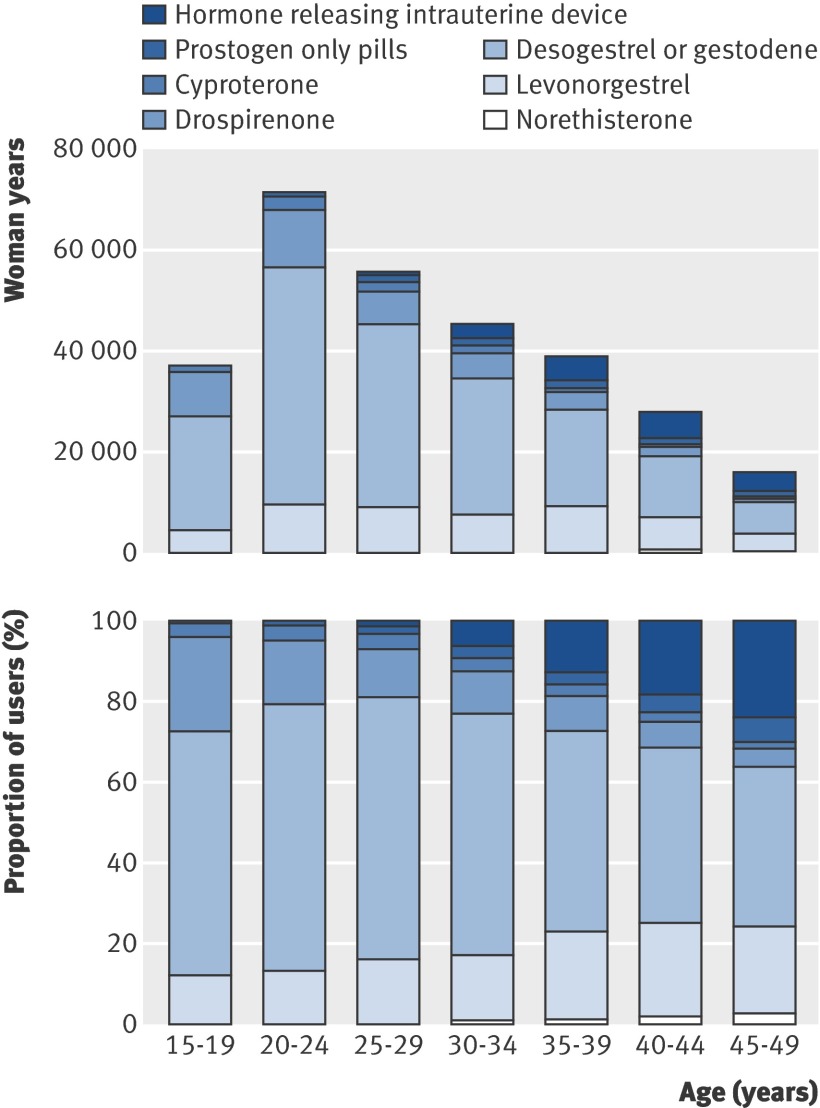

Figure 1 shows the use of different oral contraceptives by age. Generally, young women more often used newer oral contraceptives than older women, who more often used hormone releasing intrauterine devices. At the same time, the proportion of short term users was higher among young women.

Use of different types of hormonal contraception according to age and progestogen type in Denmark, 2005

The incidence of venous thromboembolism increased with age, from 1.84 per 10 000 woman years in women aged 15-19 to 6.59 per 10 000 woman years in women aged 45-49 (table 1). The incidence also increased during the 11 years of the study period, on average by 1.05 (95% confidence interval 1.04 to1.06) per calendar year. Finally, the risk of venous thromboembolism increased with decreasing education. Using the least educated women (primary school only) as the reference group, the rate ratios of venous thromboembolism for those with secondary school education only was 0.52 (0.46 to 0.59), with any schooling and three or four years of further education was 0.58 (0.54 to 0.63), and with secondary school education with five or six years of further education was 0.43 (0.39 to 0.47).

The crude incidence of venous thromboembolism among non-users (never or former use) of hormonal contraceptives was 3.01 per 10 000 woman years, and among current users of oral contraceptives was on average 6.29 per 10 000 woman years (table 1).

Combined oral contraceptives

The risk among women using combined oral contraceptives decreased with duration of use, from an adjusted rate ratio of 4.17 (95% confidence interval 3.73 to 4.66) during the first year of use to 2.76 (2.53 to 3.02) after more than four years of use (table 1).

The risk among current users of combined oral contraceptives was also influenced by oestrogen dose and type of progestogen. Table 2 shows the adjusted rate ratios for specific combinations of these three variables.

Table 2.

Observation years, number of venous thromboembolism events, crude incidence rate per 10 000 user years, and adjusted* rate ratios (95% confidence intervals) of venous thromboembolism in current users of combined oral contraceptives according to oestrogen dose, progestogen type, and length of use, with non-users of oral contraceptives as reference group

| Variables | Progestogen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norethisterone | Levonorgestrel | Norgestimate | Desogestrel | Gestodene | Drospirenone | Cyproterone | |

| Woman years | 157 962 | 411 099 | 329 463 | 676 105 | 1 332 157 | 131 541 | 126 687 |

| Thrombotic event | 71 | 238 | 151 | 442 | 928 | 103 | 90 |

| Crude rate | 4.5 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 7.1 |

| Rate ratio* | |||||||

| Oestrogen dose and duration of use | |||||||

| Oestrogen 50 μg: | |||||||

| <1 year | 2.89 (1.37 to 6.07) | 3.06 (1.53 to 6.14) | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1-4 years | 2.35 (1.30 to 4.26) | 2.00 (1.11 to 3.63) | — | — | — | — | — |

| >4 years | 4.05 (2.18 to 7.54) | 2.78 (1.75 to 4.43) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Oestrogen 30-40 μg: | |||||||

| <1 year | 2.81 (1.66 to 4.77) | 1.91 (1.31 to 2.79) | 3.37 (2.38 to 4.76) | 5.58 (4.13 to 7.55) | 4.38 (3.65 to 5.24) | 7.90 (5.65 to 11.0) | 6.68 (4.50 to 9.94) |

| 1-4 years | 1.76 (1.12 to 2.77) | 2.23 (1.78 to 2.78) | 2.27 (1.74 to 2.96) | 3.48 (2.74 to 4.42) | 3.85 (3.39 to 4.36) | 2.68 (1.86 to 3.86) | 3.24 (2.28 to 4.61) |

| >4 years | 1.55 (0.83 to 2.89) | 1.91 (1.55 to 2.36) | 2.20 (1.70 to 2.85) | 3.19 (2.53 to 4.02) | 3.34 (2.95 to 3.78) | 3.26 (2.35 to 4.54) | 3.37 (2.38 to 4.76) |

| Oestrogen 20 μg: | |||||||

| <1 year | — | — | — | 4.89 (3.83 to 6.23) | 4.43 (3.25 to 6.04) | — | — |

| 1-4 years | — | — | — | 2.83 (2.29 to 3.49) | 3.27 (2.61 to 4.10) | — | — |

| >4 years | — | — | — | 2.69 (2.17 to 3.35) | 2.79 (2.15 to 3.63) | — | — |

*All estimates adjusted for age, calendar year, and education and with non-users of oral contraceptives as reference group.

For a given progestogen type and after adjustment for length of use, the risk of venous thromboembolism decreased with decreasing dose of oestrogen (table 3). A reduction in oestrogen dose from 50 µg to 30-40 µg in oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel reduced the risk by 17% (NS), and for oral contraceptives containing norethisterone by 32% (NS). Furthermore, a reduction in oestrogen dose from 30-40 µg to 20 µg for oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene reduced the risk of venous thromboembolism by 18% (7% to 27%).

Table 3.

Adjusted rate ratios (95% confidence intervals) of venous thromboembolism in current users of combined oral contraceptives according to oestrogen dose and progestogen type after adjustment for length of use

| Variables | Progestogen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norethisterone | Levonorgestrel | Norgestimate | Desogestrel | Gestodene | Drospirenone | Cyproterone | |

| Oestrogen 50 µg: | 1.44 (0.97 to 2.14) | 1.20 (0.85 to 1.71) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Woman years | 39 211 | 43 691 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Venous thrombembolism | 28 | 37 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Oestrogen 30-40 µg: | 0.98 (0.71 to 1.37) | 1 (reference) | 1.19 (0.96 to 1.47) | 1.82 (1.49 to 2.22) | 1.86 (1.59 to 2.18) | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.10) | 1.88 (1.47 to 2.42) |

| Woman years | 118 751 | 367 408 | 329 463 | 233 883 | 1 012 977 | 131 541 | 126 687 |

| Venous thrombembolism | 43 | 201 | 151 | 191 | 744 | 103 | 90 |

| Oestrogen 20 µg: | — | — | — | 1.51 (1.25 to 1.82) | 1.51 (1.22 to 1.86) | — | — |

| Woman years | — | — | — | 442 223 | 319 180 | — | — |

| Venous thrombembolism | — | — | — | 251 | 184 | — | — |

Rate ratios adjusted for age, calendar year, education, and length of use.

Compared with current users of oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel, using the same dose of oestrogen and after adjustment for duration of use, the rate ratios of venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing norethisterone was 0.98 (0.71 to 1.37), norgestimate 1.19 (0.96 to 1.47), desogestrel 1.82 (1.49 to 2.22), gestodene 1.86 (1.59 to 2.18), drospirenone 1.64 (1.27 to 2.10), and cyproterone 1.88 (1.47 to 2.42; table 3).

Progestogen only pills

Progestogen only pills containing levonorgestrel 30 μg or norethisterone 350 μg, as well as desogestrel 75 μg did not confer any increased risk of venous thromboembolism when compared with non-users of oral contraceptives, and women using hormone releasing intrauterine devices had an adjusted rate ratio for venous thromboembolism of 0.89 (0.64 to 1.26; table 1).

Discussion

The risk of venous thromboembolism in current users of combined oral contraceptives decreases with duration of use and decreasing oestrogen dose. For the same dose of oestrogen and the same length of use, oral contraceptives containing desogestrel, gestodene, or drospirenone were associated with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism than oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel. Progestogen only pills and hormone releasing intrauterine devices did not confer any increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

The extent of an overall risk estimate of venous thromboembolism in current users of oral contraceptives depends on several factors. Exclusion of women with previous thrombosis and cancer from the reference group would increase the overall risk estimate because of the decreased risk in the reference group. The estimate would also be increased by the inclusion of relatively more new users or short term users of oral contraceptives, or if many women were using oral contraceptives that contained desogestrel, gestodene, or drospirenone compared with those containing levonorgestrel. The inclusion of pregnant women in the reference group or women using progestogen only pills in the oral contraceptives group would, however, decrease the overall estimate for oral contraceptives.

The diagnosis of venous thromboembolism has improved over time because of better diagnostic equipment. Therefore more venous thromboses would be diagnosed today than previously. As a consequence, newer absolute risk estimates would be expected to be higher than older estimates. The relative risk estimates, however, are less sensitive to this time trend, and we controlled for this in the study by including calendar year in the multivariate analyses.

These methodological circumstances may explain the apparently contradictory results from other studies. As we included non-users of oral contraceptives as our reference population, effectively excluded women with a history of cancer or cardiovascular events, had less than one third long term users, and most of the women were users of low dose oral contraceptives, our overall risk estimates for oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel, desogestrel, or gestodene are slightly lower than in previous studies and lower than the estimates in our previous study covering 1994-8.12

Our results confirm that the risk in users of combined oral contraceptives depends on the dose of oestrogen, type of progestogen, and length of use. Reducing the dose of oestrogen from 50 μg to 30-40 μg non-significantly reduced the risk of venous thromboembolism by 17-32%. Reducing the dose from 30-40 μg to 20 μg in users of oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene significantly reduced the risk of venous thromboembolism by 18% (95% confidence interval 7% to 27%), after adjustment for duration of use of oral contraceptives. Without this adjustment the association was confounded and not significant. Together with the lack of power this may explain why few studies have been able to show this dose-response relation. The dose-response relation between oral contraceptive use and venous thromboembolism strengthens the evidence that the statistical associations reflect a causal relation.

The higher risk of venous thromboembolism in users of oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene compared with those containing levonorgestrel is in line with several previous studies,1 6 7 8 9 12 although not all7 13 (table 4). According to our data, oral contraceptives with norgestimate were associated with about the same risk of venous thromboembolism as oral contraceptives with levonorgestrel. One study found an absolute risk of 4.2 (95% confidence interval 2.9 to 5.8) per 10 000 woman years in users of oral contraceptives with norgestimate,16 results in line with our 4.6 per 10 000 woman years. Our estimate was based on 151 venous thrombotic events and is higher than the estimate in our previous study, based on 18 venous thrombotic events for this specific group.12

Table 4.

Studies on oral contraception and venous thromboembolism. Risk estimates are in current users of oral contraceptives compared with non-users or never users unless stated otherwise

| Study | Period of data sampling | No with venous thromboembolism | Rate ratio (95% CI) for combined oral contraceptives | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pill with levonorgestrel | Pill with desogestrel or gestodene | Pill with drospirenone | |||

| Blomenkamp1 | 1988-92 | 126 | 3.8 (1.7 to 8.4) | 8.7 (3.9 to 19.3) | — |

| WHO3 | 1989-93 | 433 | 3.6 (1.4 to 7.9) | 7.4 (4.2 to 12.9) | — |

| Jick2 | 1991-4 | 80 | Reference | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.2) | — |

| Spitzer4 | 1991-5 | 471 | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.3) | 4.8 (3.4 to 6.7) | — |

| Lewis7 | 1993-5 | 502 | 2.9 (1.9 to 4.2) | 2.3 (1.5 to 3.5) | — |

| Farmer5 | 1991-5 | 85 | 3.1* (2.1 to 4.5) | 5.0‡ (3.7 to 6.5) | — |

| Todd8 | 1992-7 | 99 | Reference | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.8) | — |

| Bloemenkamp6 | 1994-8 | 185 | 3.7 (1.9 to 7.2) | 7.0 (NA) | — |

| Lidegaard12 | 1994-8 | 987 | 2.9 (2.2 to 3.8) | 4.0 (3.2 to 4.9) | — |

| Dinger13 | 2000-4 | 118 | Reference | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.0)† | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) |

| Seeger14 | 2001-4 | 57 | Reference | Reference | 1.0 (0.2 to 18.6) |

| Lidegaard (current study) | 1995 | 4213 | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3) | 3.6 (3.3 to 3.8) | 4.0 (3.3 to 4.9) |

WHO=World Health Organization; NA=not available.

*Incidence per 10 000 woman years.

†Our calculation based on data in publication.

Studies have shown a threefold increased risk of venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives that contain cyproterone compared with non-users,10 11 12 results similar to ours.

Three studies have been identified that assessed the risk of venous thromboembolism in users of oral contraceptives containing drospirenone.13 14 17 The European active surveillance study found 9.1 venous thrombotic events per 10 000 user years (26 events) in women using oral contraceptives that contained drospirenone compared with 8.0 per 10 000 woman years (25 events) in those using oral contraceptives that contained levonorgestrel, and 2.3 per 10 000 woman years in non-pregnant non-users (five events).13 A case only study showed a risk of venous thromboembolism in new users of drospirenone of 13.7 per 10 000 user years.17 Another study showed a similar incidence, of 13 per 10 000 drospirenone years in new users compared with 14 per 10 000 user years for other oral contraceptives, although the types were not given in the paper.14

In users of oral contraceptives containing drospirenone we found an incidence of venous thromboembolism of 7.9 per 10 000 woman years and an adjusted rate ratio of 1.64 (1.27 to 2.10) when compared with oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel, and of 4.00 (3.26 to 4.91) when compared with non-users of oral contraceptives. These estimates were based on 103 venous thrombotic events in users of oral contraceptives with drospirenone. The four times increased risk of venous thromboembolism compared with non-users is in accordance with the surveillance study.13 The higher risk of venous thromboembolism when compared with users of oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel is a new finding. The reason for this rate ratio was primarily a lower risk in users of oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel in our study compared with the same estimates in the surveillance study.13 Before general clinical recommendations are possible this finding should be confirmed in other studies, and the risk of arterial thrombosis assessed for oral contraceptives that contain drospirenone. However, the risk estimate was of the same magnitude as for oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene with the same dose of oestrogen and same length of use, results in accordance with two other studies.13 14

Finally, the lack of increased risk of venous thrombosis by use of progestogen only pills is in line with previous findings,12 although the statistical power to detect small differences was not present owing to the relatively small number of users of these products.

The reduced risk of venous thrombosis with increasing length of education could be attributed to the higher prevalence of obese women with short rather than long education.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The registry linkage design of this study had some advantages and some limitations. One strength is the high external validity, as we included all Danish women aged 15-49 who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Because of the establishment of the National Registry of Patients in 1977 we were also able to define a population with only first ever venous thromboembolism in non-pregnant women.

Recall bias was eliminated, as the national prescription registry provided precise data on use of hormonal contraception, with detailed information about the specific product and the length of use. The national approach ensured a relatively high statistical power by including 4213 venous thrombotic events. Consequently we were able to assess the risk for specific subtypes of oral contraceptives and to consider separately the importance of oestrogen dose, type of progestogen, and length of use in the risk of venous thrombosis. Finally, the cohort design allowed the calculation of absolute risk estimates as well as rate ratios between different types of hormonal contraception.

Among the limitations of our study were the lack of two potential confounders; family predisposition and body mass index. When oral contraceptives containing desogestrel or gestodene were introduced in the late 1980s they were considered safer than the older types of oral contraceptives. Therefore, women with a family predisposition for venous thromboembolism were preferentially prescribed these new pills.18 However, after new studies were published in the 1990s this preferential prescribing stopped and was not apparent during 1994-8.12

Being overweight predisposes to venous thromboembolism. If some oral contraceptives are preferentially prescribed to women with an increased body mass index, then the risk of these oral contraceptives could be overestimated. However, when we carried out the previous study on venous thromboembolism during 1994-8 we had information on body mass index and family predisposition.12 Controlling for these two potential confounders did not change the risk estimates of venous thromboembolism as a result of a weak association between body mass index and family predisposition on the one hand and different types of oral contraceptives on the other.

When the new oral contraceptive containing drospirenone was introduced in Denmark in 2001, it was not considered as safer than the older pills. Therefore preferential prescribing of this pill to women at increased risk of venous thromboembolism is not expected. This was confirmed in a surveillance study, in which the average body mass index among users of oral contraceptives containing drospirenone was 22.9 and among users of oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel was 22.0, and the percentage with a body mass index of 30 or more was, respectively, 8.2% and 5.3%.13 In our study we were able to investigate the proportion of women taking other medication in the different subgroups of users of oral contraceptives. We found the same or lower prevalence in users of oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel, suggesting the same baseline health status. In conclusion we have empirical data suggesting that bias as a result of failing to control for body mass index and family predisposition was small, if present at all.

Another limitation was that the registry approach did not permit us to evaluate the validity of each included diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. They were identified as the final discharge diagnosis as reported to the National Registry of Patients. The inclusion of about 10% uncertain diagnoses may have biased our results, however, only if the misclassification was differential, implying fewer or more women with an uncertain diagnosis among current users of oral contraceptives compared with non-users. In this study the slightly lower risk estimates among current users of oral contraceptives compared with our previous study in which these uncertain cases were excluded12 might suggest fewer users of oral contraceptives among women with an uncertain diagnosis than among those with a validated and confirmed diagnosis. The reduction in oestrogen dose of oral contraceptives through the study period, however, could also have contributed to the reduced risk estimates.

Finally, registry data do not include information about lifestyle such as being sedentary, long distance flights, and limited mobility at home. We therefore had no opportunity to explore the interaction between such conditions and use of hormonal contraception.

Clinical implications

For women of normal weight and without known genetic predispositions, we recommend a low dose combined pill as first choice for contraception. For women genetically predisposed to venous thrombosis who still want hormonal contraception, however, a progestogen only pill or hormone releasing intrauterine device seems to be the appropriate first choice.

Before firm general clinical recommendations on type of progestogen can be made we need data on the effect of drospirenone on arterial end points. For women with an increased body mass index; however, a low dose combined pill with levonorgestrel should be first choice. If the risk of arterial diseases is the same for the new progestogens as for levonorgestrel then according to our figures about 7400 women should change from the newer products to oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel to prevent one case of venous thrombosis.

What is already known on this topic

Previous studies have shown an increased risk of venous thrombosis with use of combined oral contraceptives and a higher risk with use of combined pills containing the progestogens desogestrel or gestodene than containing levonorgestrel

What this study adds

The risk of venous thrombosis in users of combined oral contraceptives decreases with decreasing dose of oestrogen

The risk of venous thrombosis from pills containing drospirenone corresponds to those containing desogestrel or gestodene and is higher than with levonorgestrel

Progestogen only pills and hormone releasing intrauterine devices did not confer any increased risk of venous thrombosis

The absolute risk of venous thrombosis with use of any types of combined oral contraceptives in young women is less than one in 1000 user years

We thank the National Registry of Medicinal Products Statistics for providing the data on use of hormonal contraception and the National Board of Health for providing the data from the National Registry of Patients.

Contributors: ØL designed the study, planned the analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. He is the guarantor and responsible investigator. EL planned the study and the analysis, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. ALS managed data from National Registry of Patients, elaborated the logistics for the identification of the pregnant women, did the statistical analyses, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. CA prepared the data from National Registry of Patients and NRM, provided data from Statistics of Denmark for the analysis, and revised the manuscript.

Funding: The Gynaecological Clinic, Rigshospitalet covered the expenses for this study.

Competing interests: ØL has received grants from pharmaceutical companies for cover of research expenses and has received fees for speeches on pharmacoepidemiological topics.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J No 2003-41-2872). Ethical approval is not requested for registry based studies in Denmark.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2890

References

- 1.Bloemenkamp KWM, Rosendaal FR, Helmerhorst FM, Büller HR, Vandenbroucke JP. Enhancement by factor V Leiden mutation of risk of deep-vein thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives containing a third-generation progestagen. Lancet 1995;346:1593-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jick H, Jick SS, Gurewich V, Myers MW, Vasilakis C. Risk of idiopathic cardiovascular death and nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives with differing progestagen components. Lancet 1995;346:1589-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Collaborative Study on Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Effect of different progestagens in low oestrogen oral contraceptives on venous thromboembolic disease. Lancet 1995;346:1582-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spitzer WO, Lewis MA, Heinemann LAJ, Thorogood M, MacRae KD. Third generation oral contraceptives and risk of venous thromboembolic disorders: an international case-control study. BMJ 1996;312:83-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmer RDT, Lawrenson RA, Thompson CR, Kennedy JG, Hambleton IR. Population-based study of risk of venous thromboembolism associated with various oral contraceptives. Lancet 1997;349:83-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloemenkamp KWM, Rosendaal FR, Büller HR, Helmerhorst FM, Colly LP, Vandenbroucke JP. Risk of venous thrombosis with use of current low-dose oral contraceptives is not explained by diagnostic suspicion and referral bias. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis MA, MacRae KD, Kühl-Habich D, Bruppacher R, Heinemann LAJ, Spitzer WO. The differential risk of oral contraceptives: the impact of full exposure history. Hum Reprod 1999;14:1493-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todd J-C, Lawrenson R, Farmer RDT, Williams TJ, Leydon GM. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: a re-analysis of the MediPlus database. Hum Reprod 1999;14:1500-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jick H, Kaye JA, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick SS. Risk of venous thromboembolism among users of third generation oral contraceptives compared with users of oral contraceptives with levonorgestrel before and after 1995: cohort and case-control analysis. BMJ 2000;321:1190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkin L, Skegg DCG, Wilson M, Herbison GP, Paul C. Oral contraceptives and fatal pulmonary embolism. Lancet 2000;355:2133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, Jick H. Risk of venous thromboembolism with cyproterone and levonorgestrel contraceptives. Lancet 2001;358:1427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lidegaard Ø, Edström B, Kreiner S. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism. A five-year national case-control study. Contraception 2002;65:187-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinger JC, Heinemann LAJ, Kühl-Habich D. The safety of a drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive: final results from the European Active Surveillance study on oral contraceptives based on 142,475 women-years of observation. Contraception 2007;75:344-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seeger JD, Loughlin J, Eng PM, Clifford CR, Cutone J, Walker AM. Risk of thromboembolism in women taking ethinylestradiol/drospirenone and other oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:587-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Venous thromboembolic disease and combined oral contraceptives: results of international multicentre case-control study. Lancet 1995;346:1575-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jick SS, Kaye JA, Russmann S, Jick H. Risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using a contraceptive transdermal patch and oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35µg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception 2006;73:223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce HM, Layton D, Wilton LV, Shakir SAW. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism reported in the prescription event monitoring study of Yasmin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;60:98-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lidegaard Ø. The influence of thrombotic risk factors when oral contraceptives are prescribed. Acta Obstet Gynaecol Scand 1997;76:252-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]