Abstract

Purpose

The Family Care Conference (FCC) is an elder-focused, family-centered, community-based intervention for the prevention and mitigation of elder abuse. It is based on a family conference intervention developed by the Maori people of New Zealand, who determined that Western European ways of working with child welfare issues were undermining such family values as the definition and meaning of family, the importance of spirituality, the use of ritual, and the value of noninterference. The FCC provides the opportunity for family members to come together to discuss and develop a plan for the well-being of their elders.

Design and Methods

Using a community-based participatory research approach, investigators piloted and implemented the FCC in one northwestern Native American community. The delivery of the FCC intervention has grown from having been introduced and facilitated by the researchers, to training community members to facilitate the family meetings, to becoming incorporated into a Tribal agency, which will oversee the implementation of the FCC.

Results

To date, families have accepted and appreciated the FCC intervention. The constructive approach of the FCC process helps to bring focus to families' concerns and aligns their efforts toward positive action.

Implications

The strength-based FCC provides a culturally anchored and individualized means of identifying frail Native American elders' needs and finding solutions from family and available community resources.

Keywords: Native American, American Indian, Family conferences, Community-based participatory research, Elder mistreatment, Elder abuse

Historically, Native American elders, as carriers of traditions and teachers of wisdom, have held unique and honored positions in their communities. Elders' greater life experience, historical perspective, spiritual knowledge, and closer ties to the ways of Tribal ancestors make them a valuable resource for younger people. Yet elder mistreatment is increasingly identified as a serious problem in Native American communities (Baldridge, 2001; National Center on Elder Abuse, 1998; National Indian Council on Aging, 1998; Nerenberg & Baldridge, 2004a, 2004b). In 2005, the New Mexico Indian Elders Forum passed a resolution for submission to the 2005 White House Conference on Aging that called for the need to “address the growing issue of elder abuse” (National Indian Council on Aging, 2005).

For Native American elders, there are major gaps in knowledge regarding definitions of abuse and neglect; the incidence, prevalence, and types of elder mistreatment; and current and preferred treatment strategies. Statistics regarding Native American elder mistreatment are often nonexistent, and state mandatory reporting structures typically do not extend to Tribal groups living on reservations due to Tribal sovereignty. Research related to problems among Native American groups is often difficult to conduct due to fears of exploitation and further pathologizing of Tribal life. Only five descriptive studies related to elder abuse among Native Americans have been reported. These investigations concerned (a) verbally reported occurrence of elder abuse on two plains reservations (Maxwell & Maxwell, 1992); (b) extent, types, and patterns of abuse, and causal variables of elder abuse among the Navajo people (Brown, 1989, 1999); (c) service providers' perspectives of elder abuse among the Navajo people (Brown, 1998); (d) a comparison of perspectives and meanings of elder abuse among seven culturally diverse groups of people, including two Native American tribes in North Carolina (Hudson, Armachain, Beasley, & Carlson, 1998); and (e) an analysis of clinic records to determine the frequency of Native American elder abuse in an urban area (Buchwald et al., 2000).

In 1986, the Administration on Aging funded three demonstration projects for Native American elder abuse prevention (Nerenberg & Baldridge, 2004a, 2004b). The activities of these projects included “the development of model abuse prevention codes, prevention and public awareness campaigns, and elder recognition events” (Nerenberg & Baldridge, 2004b, p. 12). One of the recommendations from the National Indian Council on Aging's final report on the extent and characteristics of elder abuse in Native American communities called for demonstration projects “to explore the effectiveness of traditional mediation techniques to resolve domestic violence and elder abuse” (Nerenberg & Baldridge, 2004a, p. 11).

Since the 1980s, a growing number of Tribes have adopted elder abuse codes with emphasis on legal means for addressing elder abuse. However, the fragmenting effects of legal recourse have not been satisfactory and run counter to traditional values. Carson and Hand (1998) noted that Euro-American-based legal policies emphasize punishment and criminalization of deviant behaviors and that many tribal ordinances regarding abuse mirror state statutes rather than Tribal culture. They also pointed out that “tribal communities are not often well-served by these policies developed for ‘collectivities of strangers’” (Carson & Hand, 1998, p. 92. Brown (1998) suggested that the criminalization of elder mistreatment fails to consider the relational and negotiated aspects of the caregiving role in which most abuse takes place. The long-term goals of interventions for elder mistreatment in Native American communities may better be “to heal relationships and to teach others in the community appropriate behaviors rather than to ‘punish an offender’” (Carson & Hand, 1998, p. 92).

Nerenberg (1999) highlighted the differences between direct and indirect Native American elder abuse outreach programs. Direct approaches emphasize the abusive behaviors and encourage reporting to appropriate adult protective agencies. These approaches tend to be punitive in nature. Indirect approaches, on the other hand, build on strengths of extended families and promote strategies to support them rather than highlight the abusive acts.

When considering interventions to address elder abuse in Native American communities, one may find indirect approaches more fruitful than direct ones. In these communities, it is impossible to overemphasize the importance of involving the family in protective measures against elder mistreatment. The “Indian way” consists of families working together to solve problems. Families are the foundation for social and emotional well-being for Native Americans (Sutton & Broken Nose, 1996). The purpose of this article is to describe an elder-focused, family-centered, community-based elder abuse intervention: the Family Care Conference (FCC).

The Project

The FCC, with its focus on elder well-being and safety, lies at the heart of a 5-year community-based participatory research project. We have described the formation and evolution of this research project elsewhere (Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois, & Weinert, 2004; Salois, Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, & Weinert, 2006). The Caring for Native American Elders project began as a pilot project on one reservation. After the successful completion of the pilot study, we hired and trained three Tribal women from the reservation to serve as FCC facilitators. Although not a priority for the facilitator position, these women's professional backgrounds ranged from associate of arts degrees to a master's degree. The women had strong histories of working in helping relationships and, most importantly, were known and respected in the various communities on the reservation. As long-established Tribal members, they understood the communities' norms and the intra- and interfamily variations of assimilation and traditionalism. The women took part in monthly facilitator support meetings to discuss cases and ways to approach the referred families. Additionally, the facilitators suggested project improvements based on their evolving experiences with convening and meeting with the families.

The FCC Intervention

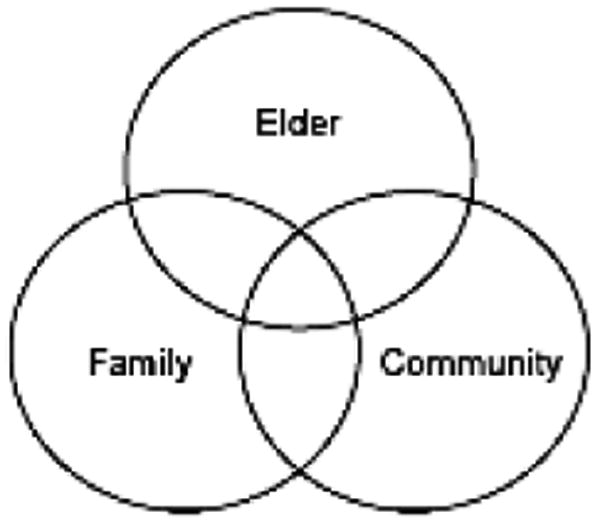

The FCC is an elder-focused, family-centered, community-based intervention for the prevention of elder mistreatment. This intervention can be represented by three intersecting circles (see Figure 1). The three circles correspond to the elder, the family, and the community. In providing services to Tribal elders, it is important to engage the family as well as the broader community. The intersection of the three circles represents the nexus wherein the elder becomes more frail and is increasingly supported by the family, who, in turn, draws on available services within the Tribal community. Those portions of the circles that do not overlap represent the autonomy of the elder and the family as well as those agencies in the community that are unnecessary for meeting the needs of the elder and the family.

Figure 1.

The Family Care Conference: elder focused, family centered, community based.

The FCC is based on a family conference intervention, the Family Group Conference, developed by the Maori people of New Zealand, who were concerned that Western European ways of addressing child welfare issues were undermining families and traditional values (Elofson, Merkel-Holguin, & Salois, 2000). Results from descriptive studies have provided some evidence that family conferences based on the Family Group Conference model protect the child while helping to unify the family group (Elofson et al., 2000; Pennell & Burford, 2000; Shore, Wirth, Cahn, Yancey, & Gunderson, 2002; Veneski & Kemp, 2000). Multiple states in the U.S. as well as other nations have adopted this model for child protection purposes (Elofson et al., 2000; Mirsky, 2003a, 2003b, 2003c; Pennell & Burford, 2000; Shore et al., 2002; Veneski & Kemp, 2000).

Although the Family Group Conference model has not been systematically used to address issues of safety and well-being for Native American elders, such an application appears logical. Researchers have noted traditional forms of this model among North American Tribal groups. In commenting on the Family Group Conference model, Lee (1997) contended that First Nations people of North America already have time-honored “principles and processes in place to deal with disharmony within the community” (p. 1). Similarly, Koss (2000) contrasted “communitarian” approaches to restoring justice with the retribution-focused approach used within the existing Euro-American-based legal system. In the communitarian approach, the victim and the offender negotiate with the intent to repair damage, whereas Euro-American legal approaches assign blame and are punitive in nature. Koss stated that less adversarial methods historically have been preferred by such indigenous societies as the “Celts, Maori, Aboriginal Australians, Inuit, Native Hawaiians, Navajo and other American Indian tribes, and Asian ethnic groups” (p. 1337). The FCC also is in close alignment with a traditional decision-making and mediation model used by one of the Plains Tribes. Akak'stiman is a spiritually focused, nonhierarchical community model in which each person's perspective is heard and valued (Crowshoe & Manneschmidt, 2002). Crowshoe and Manneschmidt indicated that, in addition to its spiritual significance, the Akak'stiman model “was always intended to find common solutions, to elicit agreements, and to establish a common understanding for future actions for the community” (p. 53). Notably, Tribes do not currently use these traditional approaches to address elder mistreatment. As a strength-focused and family-centered model, the FCC is consistent with many traditional approaches to mediation and decision making. Although many indigenous groups around the globe have accepted the Family Group Conference model (Elofson et al., 2000; Mirsky, 2003a, 2003b, 2003c; Pennell & Burford, 2000; Shore et al., 2002; Veneski & Kemp, 2000) because of the heterogeneity of the more than 550 federally recognized tribes in the United States, it is important to evaluate the cultural relevance of the FCC model through discussion with representatives from any given Tribe prior to implementation.

Native American communities have many strengths, including extended family bonds, interconnectedness within Tribal communities, and a pervasive spirituality (Cross, 1987; Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project, 2002). The elder-focused FCC emphasizes the family group. This model involves inviting family members, family-nominated supportive community members, a spiritual leader (if desired), and relevant health and social service providers to attend a meeting in which individuals bring to the forum concerns about the welfare of the elder. Once concerns have been identified and all have had the opportunity to present their perspectives, the family has the option of asking the service providers to leave the room while family members discuss the concerns and identify a plan to address them. After the family has formulated a plan, the service providers return to the family meeting to hear the plan and discuss its implementation.

The FCC Process

Although the family meeting represents the most visible component of the FCC, the intervention involves other stages that often are more important than the actual meeting. The FCC has six stages: referral, screening, engaging the family, logistical preparation, family meeting, and follow-up.

Referral

Referrals come from a variety of sources, including the Elder Protection program, Community Health Representative program, Housing Authority program, Domestic Violence program, Tribal court, Child Protection program, community members, and concerned family members. The majority of referrals are made because of concerns about exploitation, neglect, self-neglect, and child neglect. Many times referrals are related to the addiction of a family member who lives in the elder's home, exploits the elder's monthly income, or leaves young children in the care of a frail elder. Although some referrals are related to physical abuse, these are limited. In part this pattern may reflect the screening procedures, through which some referrals are deemed inappropriate.

Timeliness of response to referrals is an important concern. To address this concern, facilitators, along with the research team, developed guidelines that include making initial contact with family members within 3 to 5 days of referral receipt. Depending on the family's schedule, but within 5 working days, the facilitator determines a tentative date for the family meeting. The facilitator, although cautious to maintain confidentiality, also notifies the referring person or agency that she has begun to work with the family. This helps maintain the credibility of the FCC project in the community.

Screening

Some referrals are inappropriate for the FCC intervention. These involve families who have a high potential for violence. These situations are referred to the Elder Protection program for further evaluation and action. Over the course of this project, facilitators have developed a strong working relationship with the Elder Protection program.

Engaging the Family

The pre-meeting preparation stage is crucial to the success of the FCC. At the beginning of this stage, it is important to have the family identify a primary contact. This person, who may or may not be related by blood, is someone trusted by the family and the elder. The primary contact is familiar with the family's dynamics, and knows how to work within these dynamics. During this stage, the facilitator contacts family members and family-nominated service providers and invites them to participate in the FCC. Although they are careful to honor the wishes of the family when inviting participants, the facilitators at times sensitively inquire about family members whom they have not invited. In some instances, this provides the opportunity for the family to reconsider its decision.

The facilitator gives a verbal explanation and provides a descriptive brochure about the FCC to each nominated person. The facilitator emphasizes that the meeting will be a safe place for family members to gather to discuss their concerns. During the engagement stage, the facilitator helps to focus each family member's attention on the concern at hand: the elder's well-being and safety. This stage is complex, requiring communication skills that are nonjudgmental and sometimes therapeutic, including engaging, listening, encouraging, and giving information. Often a family member must address a multitude of feelings (such as stress, resentment, grief, shame, and anger) before he or she is able to commit to attending the FCC.

Many of the reservations in the Northwest are in rural areas, which can make contacting people difficult. Geographical distances necessitate traveling over back country roads, and severe weather may cause meetings to be rescheduled. Additionally, not all families have telephones; in such instances, the facilitator requests that another invited family member ask for that person to contact her.

Given the sensitive nature of the topic, face-to-face meetings between the family members and facilitator are preferred. This method of meeting allows for the development of trust and rapport and the expression of gentle caring. Yet it is important to consider geographically distant family members. When geographical distance precludes a family member's attendance at the meeting, the facilitator brings his or her concerns to the meeting. Some distant family members choose to participate via a conference phone call.

Additional strategies ensure privacy during this stage. When facilitators attempt to make contact by phone, they are cognizant about not leaving messages that might violate confidentiality. Similarly, when meeting an individual family member face-to-face, facilitators find it is sometimes important to meet outside of the house, where other family members or visitors cannot hear what is being said.

Because of the small size of the communities, it is important to pay attention to relationships between the facilitator and some of the families who have been referred. To date, the project has addressed this by having more than one facilitator who can work with a family in which there are no close relatives or alliances. Community norms and status differentials and their effect on the facilitator–family-member relationships are important additional considerations. For example, a community norm is for younger people to show respect to elders. Although facilitators are middle-aged and older women who are accustomed to working with people in a helping relationship, there have been situations in which expectations related to the elder–younger role have been intimidating to facilitators who were slated to work with Tribal members older than themselves. In other cases, facilitators have been reluctant to intervene in families with prominent community members. In such situations, the monthly facilitator group meetings are helpful for discussing sensitive strategies for approaching these families.

Logistical Preparation

Once the facilitator has contacted all nominated family members, service providers, and other community members (as requested by the family), she determines a mutually agreeable meeting time. The facilitator sends each prospective participant a letter summarizing the purpose of the meeting and identifying the date, time, and meeting place. On the day prior to the meeting, the facilitator calls those family members who can be reached by telephone to remind them of the meeting and to check that they are still able to attend.

Sensitivity to the venue for the family meeting is also important. Some families prefer to have the meeting in their homes; others prefer to have it at a neutral, but private, place (often in a conference room at one of the agency offices). Because gracious hospitality is a strong community norm, the meetings usually involve the sharing of food. The facilitator prepares a few trays of healthy snacks ahead of time in accordance with any dietary restrictions family members may have. In keeping with the norm of sharing, family participants take home any remaining food.

Creation of a safe, inviting, and private space is important. In situations in which not all participants share proficiency in both the Native and English languages, it is necessary to have an interpreter. In these circumstances family members choose a person whom they feel is unbiased and whom they trust. Confidentiality remains crucial, particularly in a small community. It is important to think about maintaining privacy by drawing conference room window shades for meetings held in the late evening. Participants must take into consideration solutions to barriers to participation (such as making arrangements for child care or transportation, joining via conference calls, or sending letters) prior to the meeting. Because the length of the meeting may range from 2 to 5 hr, it is important to plan for breaks so people can move about, stretch, and use the facilities.

Family Meeting

The family meeting has the following components: beginning, information sharing, development of a plan, and closing.

Beginning

As people arrive, the facilitator acknowledges and greets everyone, often with a warm handshake or a hug. The agenda for the family meeting begins with a formal welcome, during which the facilitator thanks the family for coming together and for allowing the facilitator to be a part of its meeting. This recognizes the emotional vulnerability that some family members may experience in coming together to discuss sensitive aspects of their family. The meeting opens with a prayer offered by a chosen family member (such as an elder or the oldest participant) or a spiritual leader (if the family has invited one to attend the meeting). If needed, introductions are made and each participant explains his or her relationship to the elder. The facilitator then reviews the FCC format, briefly identifying the purpose of the meeting and describing her own role. At this time, the facilitator reminds people that the sharing of their stories will be held sacred. The group spends some time establishing group norms (e.g., one person speaks at a time; show respect for all; conflict without hostility can be good; no question is wrong; no side conversations; be considerate of confidentiality; and recognize the “spirit of intent,” i.e., the positive intentions of others). The facilitator writes these on a flipchart and posts them in the room. The facilitator orients people to the room and the facility and invites them to partake of the food.

Information Sharing

During this portion of the meeting, the people present identify their concerns. The facilitator reads letters from family members who, although unable to attend the meeting, would like to participate. The facilitator records all concerns on the flipchart and posts the pages in a prominent place in the room. Throughout this stage, the facilitator is careful to point out family strengths she has learned about through the process of engaging the family members. Because facilitators are from the communities, they are aware of the norm against self-promotion and recognize that family members may be hesitant to identify their strengths.

Development of a Plan

The family has the option of asking the facilitator and all other people who are not members of the family to leave the room so it may develop a plan in private. Prior to leaving the room, the facilitator reminds the family to choose a recorder from among the people present. If the facilitator leaves the room, she should not leave the facility in case the family has questions or would like to make use of her mediation skills. In this case, the facilitator should make periodic checks on the family members to see if they have any questions or needs. In our experience, families rarely request this private time, possibly because they developed a trusting rapport with the facilitator during the engagement phase.

When the family has developed its plan, the facilitator and service providers return to the room to help the family with the logistics related to implementing the plan. For example, this may include identifying resources that are available to family members, developing a timeline for the various parts of the plan, and identifying which family member will be responsible for each part of the plan. The facilitator makes a record of the plan that she will include in a letter to each family member in the week following the FCC. If the family has indicated they would like a follow-up meeting, the facilitator notes the date and time of this meeting in the letter.

Closing

At the end of each meeting, the facilitator asks for an evaluation of the entire FCC intervention. Using the format of “likes and wishes,” the facilitator asks what it was that people liked about the process and what they wish could have been done differently. The facilitator makes it known that wishes are as readily appreciated as likes. The facilitator records both on the flipchart. We had originally developed a written survey for FCC participants to complete immediately following the meeting; however, asking the more open-ended likes-and-wishes question elicits a wider variety of (and more descriptive) responses. Additionally, doing the likes and wishes as a group provides time for a shared family debriefing.

Follow-Up

The follow-up portion of the FCC is dependent on family needs and desires. Follow-up is not case management; however, at times the facilitator agrees to implement a part of the family's plan, such as contacting a social service provider to arrange for a needed service. The facilitator carries through on this agreement and then makes certain the service is meeting the needs of the family. Follow-up meetings may be arranged when members of the family wish to meet together with a service provider (e.g., families might meet with people from housing to arrange a plan for complying with housing rules that will protect the elder while also finding suitable shelter for an addicted family member). Families may also schedule a date to get together to discuss how the plan is working and to modify it if necessary. Additionally, when family situations change, some families may reopen cases that have been closed, by requesting a second family meeting. Follow-up can provide the opportunity for positive encouragement. It is important to highlight the incremental progress that the family has made. Although family members may not have met their goals in their entirety, often they have taken steps toward their achievement. Or it may be that the family implemented an action that did not work. That, too, is progress with regard to both intent of good will and knowledge that something else must be tried.

Progress to Date

When working with Tribal communities, we have found it important to recognize that the definition of family encompasses a broad extended family whose members may or may not be related by blood (Red Horse, 1980a, 1980b). The structures of Tribal families are not so easily defined as in nuclear-family-based cultures (Weaver & White, 1997). All of the families have been very similar in terms of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, varying ages, and gender composition.

A total of 26 families have been referred for participation in an FCC. Facilitators assessed 3 families as inappropriate for the intervention because their potential for violence necessitated referral to the Tribal court. Ten families had a total of 16 meetings; 1 family is pending. Twelve families either deferred or resolved their difficulties in another way.

Of the 12 families who did not participate in an FCC, 3 sought resolution through court action. One family received help from a social worker when the elder was discharged from the hospital; another resolved its concerns during the engagement stage. Logistical circumstances prevented 5 families from convening. Only 2 families were unwilling to participate in an FCC.

Of the 10 families who participated in an FCC, 4 had two meetings and 1 had three meetings. Once a family has participated in an FCC, the preparation stage for a follow-up meeting takes on a different characteristic. A level of trust generally is present so that family members feel comfortable sharing their frustrations and successes with the facilitator and with one another.

The project has evolved to the extent that currently the Community Health Representative program delivers the intervention, which bodes well for sustainability. We recently held a training session for the agency's personnel. The research team will continue to provide technical assistance as needed. The Community Health Representative program is well known and trusted on this reservation. It has long-standing relationships with many of the families. This provides for a natural way to follow families who have participated in an FCC and to determine future needs.

Families seem to accept and appreciate the FCC intervention. The constructive approach intrinsic to the FCC process helps to bring focus to their concerns and aligns the various family members' perspectives toward positive action. Family members can reframe their perceived problems into an understanding of their family's unique characteristics. The FCC provides family members with a forum in which they are not only heard, but understood.

The acceptance and success of the FCC model may be attributed, in part, to the community's long history of respect for elders and preference for mediation over confrontation. The FCC intervention, because it emphasizes strengths over pathology, is a model that recognizes the inherent power within families (Pinderhughes, 1995). Drawing on the values of interdependence and reciprocity among Native American kin, the FCC provides a culturally anchored and individualized way to identify a frail elder's care needs and to find solutions for meeting those needs from among family members and available community resources.

Acknowledgments

This article was funded by National Institute for Nursing Research Grants P30 NR003979 to the Gerontological Nursing Intervention Research Center at the University of Iowa College of Nursing; P20 NR07790 to the Center for Research on Chronic Health Conditions in Rural Dwellers at Montana State University–Bozeman College of Nursing; R21 NR008528 Caring for Native American Elders: Phase III; and R03 NR09282-01 Caring for Native American Elders: Grasslands. Funding was also provided by the John A. Hartford Foundation Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity Scholarship Program.

Footnotes

Decision Editor: Nancy Morrow-Howell, PhD

References

- Baldridge D. The elder Indian population and long-term care. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, editors. Promises to keep: Public health policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2001. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS. A survey on elder abuse at one Native American tribe. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect. 1989;1(2):17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS. Understanding and combating elder abuse in minority communities. Long Beach, CA: Archstone Foundation; 1998. A service provider perspective of Native American elder abuse: A research report; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Brown AS. Patterns of abuse among Native American elderly. In: Tatara T, editor. Understanding elder abuse in minority populations. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald D, Tomita S, Hartman S, Furman R, Dudden M, Manson S. Physical abuse of urban Native Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:562–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson DK, Hand C. Understanding and combating elder abuse in minority communities. Long Beach, CA: Archstone Foundation; 1998. Dilemmas surrounding elder abuse and neglect within Native American communities; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cross T. Cross-cultural skills in Indian child welfare. Portland, OR: Northwest Indian Child Welfare Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Crowshoe R, Manneschmidt S. Akak'stiman: A Blackfoot framework for decision-making and mediation processes Calgary. Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elofson P, Merkel-Holguin L, Salois EM. Family group conferencing: Improving services for Indian children and families. Protecting Children. 2000;16(3):40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community-based participatory research: An approach to intervention research with a Native American community. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27:162–175. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson MF, Armachain WD, Beasley CM, Carlson JR. Elder abuse: Two Native American views. The Gerontologist. 1998;38:538–548. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. Blame, shame, and community: Justice responses to violence against women. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1332–1343. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. The newest old gem: Family group conferencing. Justice as Healing. 1997;2(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell EK, Maxwell RJ. Insults to the body civil: Mistreatment of elderly in two Plains Indian tribes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1992;7:3–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00116574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky L. Family Group Conferencing Worldwide: Part One in a Series. Restorative Practices E-Forum. [Retrieved February 17, 2007];2003a http://fp.enter.net/restorativepractices/fgcseries01.pdf.

- Mirsky L. Family Group Conferencing Worldwide: Part Three in a Series. Restorative Justice E-Forum. [Retrieved February 18, 2007];2003b http://fp.enter.net/restorativepractices/fgcseries03.pdf.

- Mirsky L. Family Group Conferencing Worldwide: Part Two in a Series. Restorative Practices E-Forum. [Retrieved February 17, 2007];2003c http://fp.enter.net/restorativepractices/fgcseries02.pdf.

- National Center on Elder Abuse. The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study: Final report. Washington, DC: American Public Human Services Association in collaboration with Westat, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- National Indian Council on Aging. American voices: Indian elders speak concerns and recommendations of participants at the 1998 National Indian Council on Aging Conference. [Retrieved August 20, 2001];1998 http://www.nicoa.org/report.htm.

- National Indian Council on Aging. Pre-WHCOA summary report. [Retrieved June 23 2006];2005 http://www.whcoa.gov/about/des_events_reports/PER_NM_05_09_05.pdf.

- Nerenberg L. Culturally specific outreach in elder abuse. In: Tatara T, editor. Understanding elder abuse in minority populations. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nerenberg L, Baldridge D. Preventing and responding to abuse of elders in Indian Country. Washington, DC: National Indian Council on Aging for the National Center of Elder Abuse; 2004a. No. 90-AP-2144. [Google Scholar]

- Nerenberg L, Baldridge D. A review of the literature: Elder abuse in Indian Country: Research, policy, and practice. Washington, DC: National Indian Council on Aging for the National Center on Elder Abuse; 2004b. No 90-AP-2144. [Google Scholar]

- Pennell J, Burford G. Family group decision making: Protecting children and women. Child Welfare. 2000;79(2):131–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes E. Empowering diverse populations: Family practice in the 21st century. Families in Society. 1995;76:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Red Horse JG. American Indian elders: Unifiers of Indian families. Social Casework. 1980a;61:490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Red Horse JG. Family structure and value orientation in American Indians. Social Casework. 1980b;61:462–467. [Google Scholar]

- Salois EM, Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Weinert C. Research as spiritual covenant. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2006;28:505–524. doi: 10.1177/0193945906286809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore N, Wirth J, Cahn K, Yancey B, Gunderson K. Long-term and immediate outcomes of family group conferencing in Washington state (June, 2001) Restorative Practices Forum. 2002 September 10;:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton CT, Broken Nose MA. American Indian families: An overview. In: McGolderick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK, editors. Ethnicity and family therapy. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project. A gathering of wisdoms: Tribal mental health: A cultural perspective. 2nd. LaConner, WA: Swinomish Tribal Community; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Veneski W, Kemp S. The Washington state family group conferencing project. In: Burford G, Hudson J, editors. Family group conferencing: New directions in community-centered child and family practice. New York: Aldne De Gruyter; 2000. pp. 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver HN, White BW. The Native American family circle: Roots of resiliency. Journal of Family Social Work. 1997;2(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]