Abstract

Background:

Haemosuccus pancreaticus (HP) is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The objective of our study was to highlight the challenges in the diagnosis and management of HP.

Methods:

The records of 31 patients with HP diagnosed between January 1997 and June 2008 were reviewed retrospectively.

Results:

Mean patient age was 34 years (11–55 years). Twelve patients had chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, 16 had tropical pancreatitis, two had acute pancreatitis and one had idiopathic pancreatitis. Selective arterial embolization was attempted in 22 of 26 (84%) patients and was successful in 11 of the 22 (50%). Twenty of 31 (64%) patients required surgery to control bleeding after the failure of arterial embolization in 11 and in an emergent setting in nine patients. Procedures included distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy, central pancreatectomy, intracystic ligation of the blood vessel, and aneurysmal ligation and bypass graft in 11, two, six and one patients, respectively. There were no deaths. Length of follow-up ranged from 6 months to 10 years.

Conclusions:

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with a history of chronic pancreatitis could be caused by HP. Diagnosis is based on investigations that should be performed in all patients, preferably during a period of active bleeding. These include upper digestive endoscopy, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and selective arteriography of the coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric artery. Contrast-enhanced CT had a high positive yield comparable with that of selective angiography in our series. Therapeutic options consist of selective embolization and surgery. Endovascular treatment can control unstable haemodynamics and can be sufficient in some cases. However, in patients with persistent unstable haemodynamics, recurrent bleeding or failed embolization, surgery is required.

Keywords: haemosuccus pancreaticus, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, chronic pancreatitis

Introduction

Haemosuccus pancreaticus (HP) is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding. This condition has been estimated to occur in about one in 1500 cases of gastrointestinal (GI) tract haemorrhage. Haemosuccus most commonly occurs in association with chronic pancreatitis and the formation of pseudoaneurysms in peripancreatic vessels. It can also occur where primary aneurysms rupture into the pancreatic duct or, more rarely, persuant to ductal calculi, villous adenomatosis or arteriovenous malformations.1 The diagnosis is not always easy to establish and often a long period elapses between the onset of the first symptoms and the precise location of the source of bleeding.

The objective of our study was to highlight the challenges involved in the diagnosis and management of HP.

Materials and methods

The records of 31 patients with HP diagnosed between January 1997 and June 2008 were reviewed retrospectively. We noteddemographic data, history, diagnostic features including symptoms, physical examination and time to diagnosis, investigations and therapeutic modalities, as well as follow-up data.

Results

The sample included 26 men and five women. Mean age was 34 years (11–55 years). Twelve patients had chronic alcoholic pancreatitis, 16 had tropical pancreatitis, two had acute pancreatitis and one had idiopathic pancreatitis. A total of 17 patients had a pseudocyst (eight in the head, six in the body and three in the tail of the pancreas). Presenting symptoms were haematemesis in 10, malena in 31 and worsening of anaemia in 30 patients. Transfusion requirements ranged from 3 units to 12 units (mean = 6 units).

Diagnosis

Upper GI endoscopy showed the presence of blood in the duodenum in 16 of 31 (51%) patients. The remaining patients had normal UGI endoscopic findings. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) was performed in all 31 patients and showed a pseudoaneurysm in 28 (90%) patients (Figs 1A, 2A, 3A). Conventional angiography was carried out in 26 patients (Fig. 1B). The pseudoaneurysm arose from the splenic artery in 17 patients, from the gastroduodenal artery in five, from a branch of the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery in one, from the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery in two and from the superior mesenteric artery in one patient. An unnamed vessel in the pseudocyst wall was the cause of bleed in four patients. A ductal communication with the splenic vein was found in one patient. Angiography enabled aetiological diagnosis in 23 of 26 (88%) cases. Abdominal ultrasonography with Doppler examination was performed in all patients and diagnosed aneurysmal bleeding in 12 patients. An arterial abnormality was found to be the principle cause in 30 of 31 (97%) patients. Thirteen pseudoaneurysms had ruptured into the pancreatic duct directly and 17 patients had bleeding into the pseudocyst (Table 1).

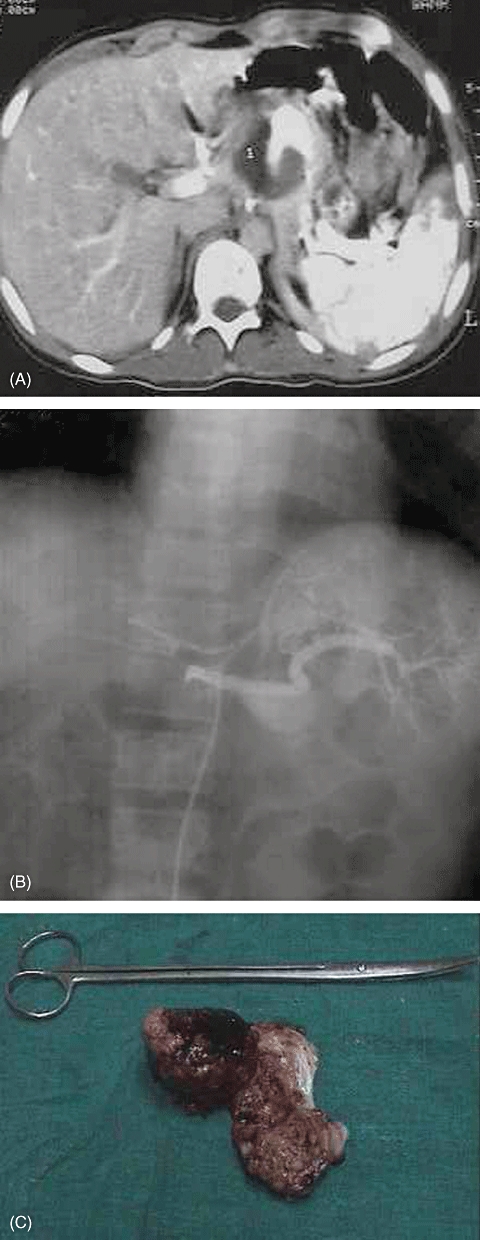

Figure 1.

(A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing a pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery. (B) Conventional angiography showing a large splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. (C) Excised pseudoaneurysm and central pancreatectomy specimen

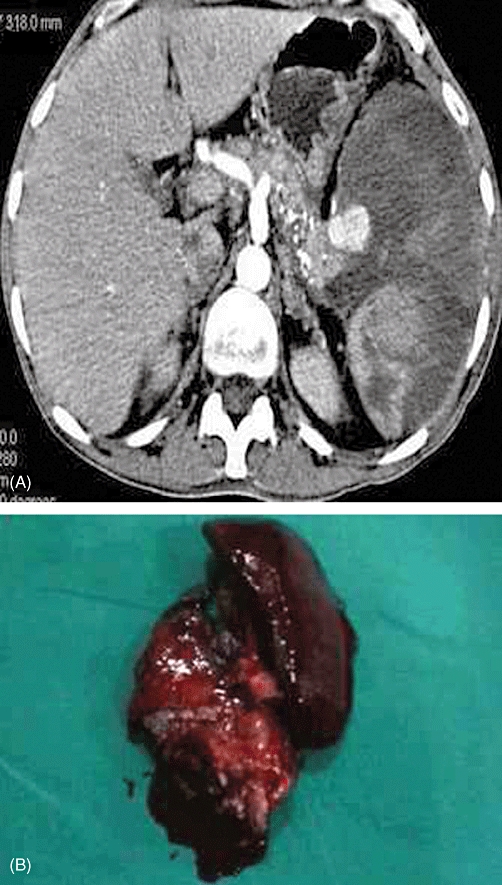

Figure 2.

(A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm against a background of chronic calcific pancreatitis. (B) Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy specimen

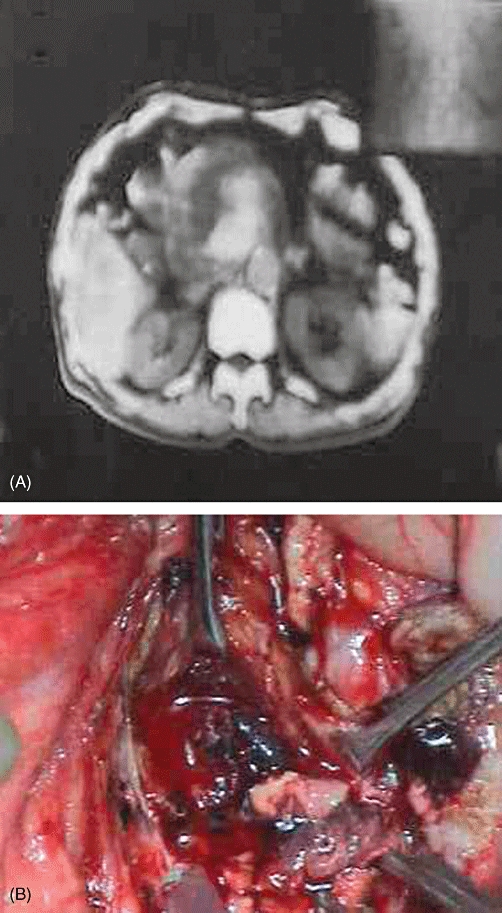

Figure 3.

Pseudoaneurysm in the head of the pancreas shown by (A) contrast-enhanced computed tomography and (B) intraoperative photography

Table 1.

Patient demographics, presenting symptoms, aetiologies and investigations in the study sample (n= 31)

| Mean age, years (range) | 34 + 12 (11–55) |

| Male : female | 26:5 |

| Presenting symptoms | |

| Haematemesis, n | 10 (8%) |

| Malena, n | 31 (65%) |

| Pain in the abdomen, n | 25 (80%) |

| Worsening anaemia, n | 30 (97%) |

| Aetiology | |

| Alcoholic chronic pancreatitis, n | 12 |

| Tropical chronic pancreatitis, n | 16 |

| Alcoholic acute pancreatitis, n | 02 |

| Idiopathic pancreatitis, n | 1 |

| Transfusion requirements, units (range) | 6 (3–12) |

| Investigations, positive yield | |

| Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy | 16/31 (51%) |

| Ultrasound and Doppler study | 12/31 (38%) |

| Contrast-enhanced computed tomography | 28/31 (90%) |

| Selective angiography | 23/26 (88%) |

Management

Selective arterial embolization was attempted in 22 of 26 (84%) patients and was successful in 11 of these 22 (50%). Twenty of 31 (64%) patients required surgery to control bleeding after the failure of arterial embolization in 11 and in an emergent setting in nine patients. Procedures included distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (Fig. 2B) in 11 cases, central pancreatectomy (Fig. 1C) in two cases, intracystic ligation of the blood vessel (Fig. 3B) in six cases and aneurysmal ligation and bypass graft in one case (Table 2). There were no deaths. Morbidity included external pancreatic fistula in two patients (both were managed conservatively), wound infection in two, incisional hernia in one and pneumonia in one patient.

Table 2.

Management strategies in the study sample (n= 31)

| Angiographic embolization | 11/31 (36%) |

| Attempted | 22/26 (84%) |

| Successful | 11/22 (50%) |

| Surgery | 20/31 (64%) |

| Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy | 11 |

| Central pancreatectomy | 2 |

| Intracystic ligation of blood vessel | 6 |

| Aneurysmal ligation and bypass graft | 1 |

Follow-up

Length of follow-up ranged from 6 months to 10 years. Three patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 28 patients, none of whom experienced recurrent bleeding. Three of the patients with chronic pancreatitis who had undergone previous embolization developed intractable pain and needed drainage procedures.

Discussion

The term ‘haemosuccus pancreaticus’ was first coined by Sandblom2 in 1970 to describe the syndrome of GI bleeding into the pancreatic duct, manifested by bleeding through the ampulla of Vater. The condition was first described in 1931 by Lower and Farell,3 since when about 125 cases have been reported in the literature.4,5

Haemosuccus pancreaticus is observed predominantly in men (sex ratio: 7:1), especially in relation to chronic alcohol intake. Mean age at onset is about 50 years when the pancreatic parenchyma is involved and about 60 years when the condition is of purely arterial origin.6 Clinical symptoms and signs include UGI bleeding as evidenced by haematemesis and malena, of which malena is more common, and epigastric pain resulting from the elevation of pressure in the pancreatic ducts caused by blood clots.7,8 The haemorrhage is usually intermittent, repetitive and, most often, not severe enough to cause haemodynamic instability despite the usual arterial origin of bleeding.9 Other clinical signs are more exceptional and include: jaundice by pancreaticobiliary reflux secondary to clot formation;5,7 vomiting; weight loss, and a palpable pulsating mass with a systolic thrill in the event of aneurysm. Iron deficiency is frequent, but liver function test is normal apart from increased serum bilirubin in the event of pancreaticobiliary reflux. Serum amylase is normal outside episodes of acute pancreatitis.8

In 80% of cases, HP complicates an underlying pancreatic disease; 20% of cases correspond to a vascular anomaly.5 In our series, as in others, chronic pancreatitis was the main cause. Several mechanisms may be involved:5

the natural course of a pseudocyst may produce HP, either because the pseudocyst is haemorrhagic or because it communicates with and erodes a pericystic artery10;

HP may result from vascular ulceration caused by an intraductal stone;

HP may result from vascular ulceration caused by a dilated and cystic main pancreatic duct, and

arterial aneurysm and pseudoaneurysm, known to have a higher frequency in chronic pancreatitis (10%), may develop.11,12

Aneurysm and chronic pancreatitis are often associated, but no causal relationship has been clearly established. Other pancreatic causes of HP are rare and include neuroendocrine tumour,5 ectopic pancreas13 and pancreas divisum.14 During an episode of acute pancreatitis, HP can occur after necrosis of an arterial wall (duodenopancreatic arcade, gastroduodenal artery, splenic artery). Finally, HP can occur as a complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

It is difficult to diagnose HP because the bleeding is usually intermittent. An endoscopic examination of the UGI tract may reveal the bleeding to be from the pancreatic duct. It can also be normal and rule out other causes of upper digestive bleeding (erosive gastritis, peptic ulcers, oesophageal and gastric fundus varices). Ultrasonography can be used to visualize pancreatic pseudocysts or aneurysm of the peripancreatic arteries. Doppler ultrasound or dynamic ultrasound has been reported to be diagnostic.11,15 Contrast-enhanced CT is an excellent modality for demonstrating the pancreatic pathology and can also demonstrate features of chronic pancreatitis, pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms.16 On pre-contrast CT, the characteristic finding of clotted blood in the pancreatic duct, known as the sentinel clot, is seldom seen.17 Computed tomography may show simultaneous opacification of an aneurysmal artery and pseudocyst or persistence of contrast within a pseudocyst after the arterial phase. Again, these findings are only suggestive of the diagnosis. In our series, CECT was diagnostic in 28 of 31 (90%) cases.

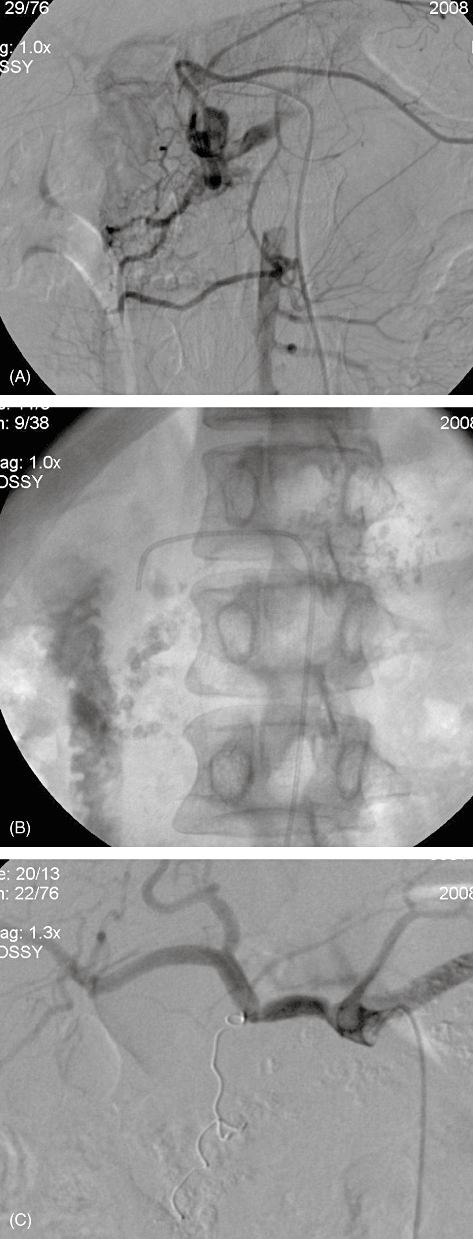

Ultimately, angiography is the diagnostic reference standard. Angiography identifies the causative artery and allows for delineation of the arterial anatomy and therapeutic intervention. Selective arteriography of the coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric artery provides formal proof of HP in the form of opacification of the main pancreatic duct (Fig. 4). It can also identify the presence of an aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm. Its sensitivity reaches 96%.18

Figure 4.

Angiography showing (A) opacification of the pancreatic duct caused by gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm, (B) dye in the duodenum and (C) post-embolization (with coils)

Haemosuccus pancreaticus is an entity diagnosed on clinical, endoscopic and radiological findings, and a definitive diagnosis can be established only with angiography. However, haemorrhage from the papilla of Vater is rarely revealed with endoscopy and the fistula between the pancreatic duct and aneurysm of the peripancreatic vessels are seldom found with angiography and thus up to 52.9% of cases do not achieve definitive diagnosis in some series.19 In such cases, HP was suspected as a result of findings of GI bleeding and an aneurysm of the peripancreatic vessels in CECT, and treatment for an aneurysm was then instituted.19 Overall, the diagnosis of HP requires a high index of suspicion in patients with pancreatitis and GI bleeding.

There are two therapeutic options for this entity: surgery and angiographic embolization. Once the haemodynamic situation is under control, interventional radiographic methods are used for initial treatment, with immediate good results in 60–100% of cases (50% in our series).14,20,21 Coil embolization techniques provoke a thrombus in the aneurysm, but also obliterate the artery.22 Ischaemia can develop in the tissue supplied by the artery if the collateral circulation is not sufficient. Embolization of the coeliac trunk, the common hepatic artery or the superior mesenteric artery is thus contraindicated. Other complications are aneurysm infection and splenic infarction (which occurred in one patient in our series). Some authors21,23 have reported that patients are free of recurrent bleeding after exclusive endovascular treatment. Others16 have found recurrence rates to the order of 30%. Angiographic intervention of a haemorrhage from pseudoaneurysm in HP can be carried out either to stabilize the patient in order to perform elective surgery or as a definitive treatment. Endovascular treatment by embolization is effective in most patients, but there is no consensus concerning the need for associated surgery to achieve complete cure. As observed by Lermite et al.,24 certain authors21,23 have reported that patients are free of recurrent bleeding after exclusive endovascular treatment. Other authors16,25 have reported recurrence rates of around 30%. In our series, selective arterial embolization was attempted in 22 of 26 (84%) patients and was successful in 11 of the 22 (50%); the remaining patients required surgical management. Failure of catheter embolization may result from factors such as inability to isolate the bleeding vessel, incomplete arterial occlusion, or misidentification of the bleeding vessel. If a conservative transarterial approach is selected in a patient with chronic pancreatitis, the remaining diseased pancreas adjacent to the previously injured artery may be the source of re-occurrence of arterial injury and bleeding.11,19,24 With increasing expertise and the use of super-selective angiocatheters, therapeutic embolization can serve as a definitive management strategy.

Surgical treatment is indicated in uncontrolled haemorrhage, persistent shock and when embolization is not feasible or when embolization fails (continued or recurrent bleeding), as well as in patients who have other indications for operative intervention (pseudocyst, pancreatic abscess, gastric outlet obstruction, obstructive jaundice or incapacitating pain) and are otherwise appropriate surgical candidates.26 In our series, 20 of 31 (64%) patients required surgery to control bleeding after the failure of arterial embolization in 11 cases and in an emergent setting in nine. Conservative surgery by ligature of the pancreatic ducts has been used but results are unsatisfactory because the causal lesion remains intact. Arterial ligation is also effective, but it does not avoid the risk of recurrence. Drainage of the pancreatic pseudocysts associated with arterial ligation is particularly effective and is associated with fewer complications of infection and necrosis compared with aggressive surgery. More aggressive surgery with pancreatic resection enables the treatment of both the pancreatic and arterial diseases. Surgical procedures in our series included distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (n= 11), central pancreatectomy (n= 2), intracystic ligation of the blood vessel (n= 6), and aneurysmal ligation and bypass graft (n= 1). In patients with chronic pancreatitis, pancreaticoduodenectomy or splenopancreatectomy are preferred by certain authors,10,19 but the problems of potential perioperative complications and postoperative pancreatic insufficiency should not be overlooked. Less radical approaches such as central pancreatectomy and intracystic ligation of pseudoaneurysm can be performed in place of pancreaticoduodenectomy. In six of our patients, we were able to avoid major resections. Most surgical series have documented success rates of 70–85%, with mortality rates of 20–25% and rebleeding rates of 0–5%.4,24,27–29

Conclusions

Upper GI bleeding in a patient with a history of chronic pancreatitis could be caused by HP. Diagnosis is based on investigations that should be performed in all patients, preferably during a period of active bleeding. These include upper digestive endoscopy and CECT and selective arteriography of the coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric artery. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography had a high positive yield comparable with that of selective angiography in our series. Therapeutic options consist of selective embolization and surgery. Endovascular treatment can control unstable haemodynamics and can be sufficient in the some cases. However, in patients with persistent unstable haemodynamics, recurrent bleeding or failed embolization, surgery is required.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Callinan AM, Samra JS, Smith RC. Haemosuccus pancreaticus. Aust N Z J Surg. 2004;74:395–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandblom PH. Gastrointestinal haemorrhage through pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1970;171:61–66. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197001000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lower WE, Farrell JT. Aneurysm of the splenic artery: report of a case and review of literature. Arch Surg. 1931;23:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etienne S, Pessaux P, Tuech J-J, Lada P, Lermite E, Brehant O, et al. Haemosuccus pancreaticus: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:237–242. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)80755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peroux JL, Arput JP, Saint-Paul MC, Dumas R, Hastier P, Caroli FX, et al. Wirsungorragie compliquant une pancréatite chronique associée á une tumeur neuroendocrine du pancréas. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18:1142–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frayssinet R, Sahel J, Sarles H. Les wirsungorragies. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1978;2:993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suter M, Doenez F, Chapuis G, Gillet M, Sandblom P. Haemorrhage into pancreatic duct (haemosuccus pancreaticus) recognition and management. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:887–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiki T, Hatori T, Imaizumi T, Harada N, Fukuda A, Kamikozury H, et al. Two cases of haemosuccus pancreaticus in which haemostasis was achieved by transcatheter arterial embolization. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:450–454. doi: 10.1007/s00534-003-0841-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SS, Roberts RR, Nagy KK, Joseph K, Bokhari F, An G, et al. Haemosuccus pancreaticus after penetrating trauma to the abdomen. J Trauma. 2000;49:948–950. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200011000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnaud JP, Bergamashi R, Serra-Maudet V, Casa C. Pancreatoduodenectomy for haemosuccus pancreaticus in silent chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1994;129:333–334. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420270111023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Risti B, Marincek B, Jost R, Ammann R. Haemosuccus pancreaticus as a source of obscure upper gastrointestinal bleeding: three cases and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1878–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.el Hamel A, Parc R, Adda G, Bouteloupas G, Huguet C, Malafosse M, et al. Bleeding pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms in chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1059–1063. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meneu JA, Fernandez-Cebrian JM, Alvarez-Baleriola I, Barrassa A, Morales V, Carda P. Haemosuccus pancreaticus in a heterotopic jejunal pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:177–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stabile BE, Wilson SE, Debas HT. Reduced mortality from bleeding pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms caused by pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1983;118:45–51. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390010035009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benz CA, Jakob P, Jakobs R, Riemann J. Haemosuccus pancreaticus – a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding: diagnosis and interventional radiological therapy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:428–431. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Perrot M, Berney T, Buhler L, Delgadicto X, Mentha G, Morel P. Management of bleeding pseudoaneurysms in patients with pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:29–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koizumi J, Inoue S, Yonekawa H, Kuneida T. Haemosuccus pancreaticus: diagnosis with CT and MRI and treatment with transcatheter embolization. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergert H, Hinterseher I, Kersting S, Leonhoadt J, Bloomenthel A, Saeger HD, et al. Management and outcome of haemorrhage due to arterial pseudoaneurysms in pancreatitis. Surgery. 2005;137:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohl JL, Dossett LA, Grau AM. Gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm associated with haemosuccus pancreaticus and obstructive jaundice. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;12:1752–1754. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0231-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahn LA, Kamen C, McNamara MP., Jr. Variable colour Doppler appearance of pseudoaneurysm in pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:187–188. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.1.8273662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambiez LP, Ernst OJ, Merlier OA, Porte HL, Chambon JP, Quantalle PA. Arterial embolization for bleeding pseudocysts complicating chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1997;132:1016–1021. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430330082014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akpinar H, Dicle O, Ellidokuz E, Okan A, Goktay Y, Tankurt E, et al. Haemosuccus pancreaticus treated by transvascular selective arterial embolization. Endoscopy. 1999;31:213–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huizinga WK, Kalideen JM, Bryer JV, Bell PS, Baker LW. Control of major haemorrhage associated with pancreatic pseudocysts by transcatheter arterial embolization. Br J Surg. 1984;71:133–136. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lermite E, Regenet N, Tuech J-J, Pessaux P, Meurette G, Bridoux V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of haemosuccus pancreaticus: development of endovascular management. Pancreas. 2007;34:229–232. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31802e0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boudghene F, L'Hermine C, Bigot JM. Arterial complications of pancreatitis: diagnosis and therapeutic aspects in 104 cases. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1993;4:551–558. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(93)71920-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh G, Lobo DR, Jindal A, Marwaha RK, Khanna SKI. Splenic arterial haemorrhage in pancreatitis: report of three cases. Surg Today. 1994;24:752–755. doi: 10.1007/BF01636785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bender JS, Bouwman DL, Levison MA, Weaver DN. Pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms: surgical strategy. Pancreas. 1995;10:143–147. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath DI, Reid AW, Murray WR. Bleeding pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms in chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1992;79:281. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waltman AC, Luers PR, Athanasoulis CA, Warshaw AL. Massive arterial haemorrhage in patients with pancreatitis. Complementary roles of surgery and transcatheter occlusive techniques. Arch Surg. 1986;121:439–443. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400040077012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]