Abstract

Epidemiologic research shows that pets influence human health, demonstrating both protective and deleterious health risks; therefore, valid definitions of pet exposure would enhance research. The authors determined how well young adults aged 18 years report their early childhood pets. Subjects in an established birth cohort from Detroit, Michigan, born in 1987–1989 (n = 820) were asked a series of questions about pets in the home during their first 6 years of life. Pet recall was compared with annual prospectively collected parental report from 12–18 years prior. Exposure to cats was correctly reported on average 86.3% of the time (95% confidence interval: 85.0, 87.5) and dogs 79.2% (95% confidence interval: 77.7, 80.6) of the time (P < 0.01). Cats and dogs were more likely to be underreported than overreported, from as few as 1.8-fold to as many as 8.3-fold (P < 0.05). Reporting differed by sex of the respondent and current pet ownership. No differences were found in reporting by those who experienced allergy symptoms near dogs or cats. Findings suggest good reliability of young adult pet reporting for ages 0–6 years but that childhood pet exposure may need to be assessed separately depending on the participant's sex and the outcome of interest.

Keywords: animals, domestic; asthma; cats; cohort studies; dogs; hypersensitivity; mental recall; validation studies

Epidemiologic research suggests that pet exposure may influence human health starting in utero and continuing into adulthood (1–9). Several large birth-cohort studies investigating early-life factors related to allergic disorders have particularly focused on the role of pets (1–3). Pets have exhibited both protective and deleterious associations with human health, and investigations into the effects of pet exposure on health will likely continue.

Although a number of birth cohort studies have obtained prospectively collected pet data (1–3), in numerous studies exposure history is based on participant recall (4–7). In many such studies, childhood pet ownership (i.e., number of cats and/or dogs) is based on self-report without additional measures to verify or ensure accuracy of the report, potentially leading to bias and conflicting results. There is little evidence in the literature to quantify the accuracy of self-report of this important information for epidemiologic investigations (8). Our goal in these analyses was to determine the accuracy of self-reported early childhood pet exposure by participants aged 18 years in a birth cohort study by comparing their reports with prospective data on household pets collected from their parents by annual questionnaires during the participants’ first 6 years of life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject recruitment and selection

The methodology for the Childhood Allergy Study has been fully described elsewhere (9). In summary, pregnant women aged 18 years or older from a geographically defined area of metropolitan Detroit, Michigan, who belonged to a health maintenance organization affiliated with the Henry Ford Health System and had an estimated date of confinement between April 15, 1987, and August 31, 1989, were eligible for the study. Study enrollment included providing written informed consent, completing a predelivery interview, and having cord blood collected at delivery. Women were asked to complete annual telephone questionnaires on the anniversary of their child's birth until (and including) the child's sixth birthday. Answers to questions on environmental exposures, including household pets, were obtained in these yearly interviews in addition to information on the child's allergic and nonallergic disease outcomes. Upon conclusion of the Childhood Allergy Study, 835 families remained eligible for enrollment in follow-up studies.

Recently, we contacted this original Childhood Allergy Study cohort of 835 children to obtain updated health information through age 18 years. After their 18th birthday, teens were contacted to complete 1) a telephone-administered interview and 2) a clinical evaluation.

Of the 835 teens eligible when the Childhood Allergy Study ended, 15 withdrew from the study or otherwise became ineligible prior to the follow-up at age 18 years. Of the remaining 820 teens, 48 were unable to be evaluated (40 could not be contacted, 3 were enlisted in the military, 3 had medical conditions precluding them from a personal interview, and 2 were incarcerated), leaving 772 teens eligible to participate. Of the 772 teens eligible, 670 (86.8%) consented to study enrollment. The Henry Ford Health System Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of the Childhood Allergy Study.

Data collection

The telephone questionnaire administered to teens addressed items on lifetime exposure to animals and to cigarette and/or other forms of smoke, physical activity, family history of allergic disease, and residential characteristics in addition to including demographic questions. Allergic disease outcomes were also assessed.

Prospective evaluation of pet keeping was reported by families (usually the mother) at the time of the annual interviews during the first 6 years of life. Pet keeping was worded as such: Have you had any pets in your home for more than 2 weeks? If a household pet was present, the type of animal and number of each type of animal were recorded as well as whether these animals were kept mostly indoors, outdoors, or equally indoors and outdoors.

Retrospective report of pet keeping was given by participants aged 18 years. Specifically, they were asked, Have you ever lived with any pets or outdoor animals? Follow-up questions included the types of animals owned and whether these animals were indoor or outdoor animals. Animals were categorized as indoors if the teen reported that the animal stayed indoors for 12 or more hours per day. If the teen had any pets other than fish, they were asked, Please list all [indoor/outdoor] pets that you have ever lived with for at least 1 month. For each pet listed, information was recorded on the type of pet, age of the participant when living with the pet, categorization of amount of contact with the animal, and whether the pet was allowed in the bedroom. In addition, for all cats or dogs listed, pet breed and weight were captured.

Also obtained from the interview at age 18 years, “animal allergy” was classified based on the teen's report of symptoms. For these analyses, cat or dog allergy at age 18 years was defined as the teen currently reporting at least one of the following symptoms when around the pet: coughing, wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, having a runny or stuffy nose or starting to sneeze, getting itchy or watery eyes, or developing hives. “Ever” asthma status was based on the teen's report of having received a prior diagnosis of asthma by a physician. “Current” asthma was defined as ever having had a physician diagnosis of asthma and at least one of the following in the 12 months prior to his or her telephone interview: having asthma symptoms, having an asthma attack, or taking prescription medications for asthma.

Statistical analyses

Pet keeping as reported by parents in the prospective annual interviews was considered as “truth.” The kappa statistic with 95% confidence intervals was used to measure agreement beyond chance alone between annual parental report and teen recall of pet keeping. In this study, if teen recall agreed with parental report and parental report was “truth,” then kappa is also a chance-corrected accuracy measure. A kappa coefficient of 1.00 indicates perfect agreement, whereas a value of 0.00 indicates no agreement beyond that expected by chance. Guidelines for interpreting kappa statistics as established by Landis and Koch (10) were applied, with values of 0.81–1.00 considered “almost perfect,” 0.61–0.80 “substantial,” 0.41–0.60 “moderate,” 0.21–0.40 “fair,” and less than 0.21 “slight” to “poor.” Differences in kappa values within each stratum were tested with a chi-square statistic (11).

The McNemar test of symmetry was used to determine whether underreporting was equal to overreporting by teens whose pet recall did not agree with the prospective parental report. Cochran-Armitage tests for trend were used to evaluate trends in animal reporting over time. Because pet keeping may be differentially reported depending on important characteristics of the participant, stratification was used to assess for effect modification. Asthma status (current as well as ever), clinical atopy to cats and dogs, and self-reported allergy to cats and dogs were all assessed as potential effect modifiers.

RESULTS

Teens who participated (n = 670) were on average 18.3 years of age, with 317 (47.3%) male and 645 (96.3%) Caucasian. Asthma status was known for 664 (99.1%) of participating teens (for 6 teens, asthma status was incomplete), with current asthma reported in 59 (8.9%) of teens and 145 (21.8%) teens ever being diagnosed with asthma. Two hundred one teens (30.0%) reported allergic symptoms around cats, and 104 (15.5%) of all teens reported these symptoms around dogs.

Table 1 presents teens’ report of pets in comparison to prospectively reported pets by parents when the teen was a young child. In this analysis, cats and dogs were each dichotomously categorized as present or not during each of the first 6 years of life. Because all families did not complete every annual interview, the denominator varied by year of life. The presence of cats was correctly reported on average 86.3% of the time (range, 85.0%–87.5%) and dogs 79.2% of the time (range, 77.7%–80.6%), with this difference being statistically significant (P < 0.01). Both cats and dogs were more likely to be underreported than overreported. Degree of underreporting (percentage underreporting divided by percentage overreporting) ranged from as little as 1.8-fold for dogs in the sixth year to as much as 8.3-fold for cats in the second year (for each age, McNemar's test for symmetry P < 0.05). Overreporting of animals was significantly more frequent with increasing age during childhood (Cochran-Armitage test for trend P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Teen Recall Versus Prospective Reporting of Pets Regarding Any Indoor or Outdoor Cats or Dogs Versus None, Childhood Allergy Study Birth Cohort, Detroit, Michigan, 1987–2008

| Year of Life | No. | Cats |

Dogs |

||||||||||||||

| Correct Report |

Underreporta |

Overreportb |

Kappac | 95% CL | Correct Report |

Underreporta |

Overreportb |

Kappac | 95% CL | ||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||||||

| First | 594 | 507 | 85.4 | 75 | 12.6 | 12 | 2.0 | 0.50 | 0.41, 0.59 | 458 | 77.1 | 120 | 20.2 | 16 | 2.7 | 0.48 | 0.41, 0.55 |

| Second | 553 | 481 | 87.0 | 64 | 11.6 | 8 | 1.4 | 0.58 | 0.49, 0.66 | 449 | 81.2 | 91 | 16.5 | 13 | 2.4 | 0.57 | 0.50, 0.64 |

| Third | 455d | 406 | 89.2 | 40 | 8.8 | 9 | 2.0 | 0.60 | 0.50, 0.70 | 365 | 80.4 | 65 | 14.3 | 24 | 5.3 | 0.53 | 0.45, 0.61 |

| Fourth | 507 | 437 | 86.2 | 57 | 11.2 | 13 | 2.6 | 0.54 | 0.45, 0.63 | 407 | 80.3 | 77 | 15.2 | 23 | 4.5 | 0.56 | 0.49, 0.63 |

| Fifth | 527 | 452 | 85.8 | 53 | 10.1 | 22 | 4.2 | 0.54 | 0.46, 0.63 | 419 | 79.5 | 73 | 13.9 | 35 | 6.6 | 0.55 | 0.47, 0.62 |

| Sixth | 508 | 430 | 84.6 | 54 | 10.6 | 24 | 4.7 | 0.56 | 0.48, 0.65 | 392 | 77.2 | 74 | 14.6 | 42 | 8.3 | 0.52 | 0.45, 0.60 |

Abbreviation: CL, confidence limits.

Defined as when a teen reported having no cats or dogs during a particular age, while the parent reported having one or more cats or dogs at the time of the original Childhood Allergy Study interview.

Defined as when a teen reported having one or more cats or dogs during a particular age, while the parent reported having no cats or dogs at the time of the original Childhood Allergy Study interview.

0.81–1.00: “almost perfect”; 0.61–0.80: “substantial”; 0.41–0.60: “moderate” (10).

For 1 family, data on dogs were missing.

Kappa statistics for total cat and dog recall are also reported in Table 1. Level of agreement, and therefore accuracy, was similar for both teen recall of the presence of cat(s) and teen recall of the presence of dog(s) (P > 0.05 for each of the 6 years). As measured by kappa coefficients and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals, more accurate recall of cats by those with a history of asthma was observed during one year (the fifth year of life) compared with those without a history of asthma (P < 0.05, data not shown). Differences in reporting of dogs by asthma status were not statistically significant for any of the 6 years (all P > 0.05, data not shown). A similar association was seen for those with current asthma (not shown).

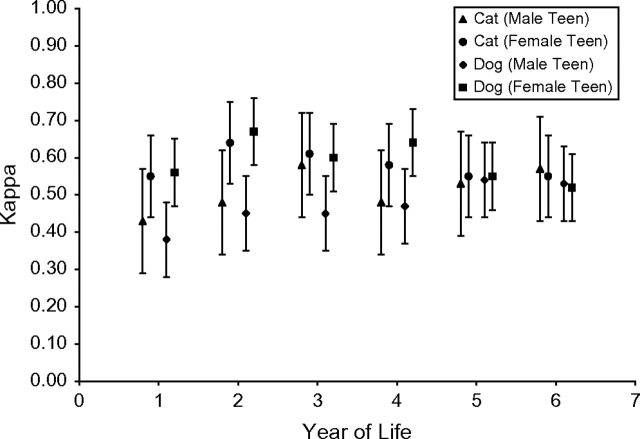

Figure 1 shows pet recall by sex of the teen. Females tended to more accurately recall their early-childhood dogs than did their male counterparts, with differences achieving statistical significance (P < 0.05) for the first, second, and fourth years of life, but not from ages 5 to 6 years. Females also tended to more accurately report their cats in the first 4 years of life; however, differences between male and female reporting of cats did not achieve statistical significance (all P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Teen recall of indoor and outdoor cats and dogs, any pets versus none, by the sex of the teen in the Childhood Allergy Study birth cohort, Detroit, Michigan, 1987–2008. Shown are kappa with 95% confidence limit.

Table 2 shows teen recall stratified by current dog and cat ownership. Teens with one or more dogs in their home at age 18 years were significantly less likely to recall their childhood dogs for the first, second, fourth, fifth, and sixth years of life than teens without a dog in the home (P < 0.05). Teens with one or more cats in the home at age 18 years were significantly less likely to recall their cats in the fourth and sixth years of life than were teens without cats (P < 0.05). Teen recall was also stratified by self-reported allergy symptoms to cats and dogs. Teens with symptoms around either cats or dogs were as accurate in their reporting of childhood cats and dogs as those without symptoms (all P > 0.05, data not shown).

Table 2.

Teen Recall of Indoor and Outdoor Dogs and Cats, Adjusted by Pet Ownership at Age 18 Years, in the Childhood Allergy Study Birth Cohort, Detroit, Michigan, 1987–2008

| Year of Life | Recall of Dogs |

Recall of Cats |

||||||||||||

| No Dog at Age 18 Years |

Dog at Age 18 Years |

P Value | No Cat at Age 18 Years |

Cat at Age 18 Years |

P Value | |||||||||

| No. | Kappaa | 95% CL | No. | Kappaa | 95% CL | No. | Kappaa | 95% CL | No. | Kappaa | 95% CL | |||

| First | 243 | 0.57 | 0.46, 0.69 | 351 | 0.42 | 0.33, 0.51 | <0.05 | 390 | 0.50 | 0.38, 0.63 | 204 | 0.45 | 0.33, 0.58 | 0.58 |

| Second | 225 | 0.68 | 0.57, 0.79 | 328 | 0.50 | 0.41, 0.59 | <0.05 | 370 | 0.63 | 0.51, 0.75 | 183 | 0.48 | 0.36, 0.60 | 0.08 |

| Third | 186 | 0.63 | 0.49, 0.77 | 2,698b | 0.47 | 0.36, 0.57 | 0.07 | 314 | 0.63 | 0.48, 0.79 | 141 | 0.52 | 0.37, 0.66 | 0.26 |

| Fourth | 212 | 0.69 | 0.58, 0.81 | 295 | 0.47 | 0.37, 0.57 | <0.01 | 347 | 0.61 | 0.47, 0.76 | 160 | 0.40 | 0.27, 0.53 | <0.05 |

| Fifth | 221 | 0.65 | 0.53, 0.76 | 306 | 0.47 | 0.37, 0.57 | <0.05 | 356 | 0.58 | 0.44, 0.71 | 171 | 0.44 | 0.31, 0.57 | 0.15 |

| Sixth | 211 | 0.66 | 0.55, 0.78 | 297 | 0.41 | 0.31, 0.51 | <0.01 | 345 | 0.61 | 0.48, 0.73 | 163 | 0.42 | 0.29, 0.55 | <0.05 |

Abbreviation: CL, confidence limits.

0.81–1.00: “almost perfect”; 0.61–0.80: “substantial”; 0.41–0.60: “moderate” (10).

For 1 family, data on dogs were missing.

Teen recall was further assessed by original parental report if the dog(s) or cat(s) was 1) mainly indoors, 2) equally indoors and outdoors, or 3) mostly outdoors to test whether pets that spent more time in the home were more often recalled by teens. Recall of cats did not significantly differ by categorization of time indoors during any of the 6 years (all P > 0.05, data not shown); however, recall of dogs did differ for the fourth and fifth years of life, with, on each occasion, dogs equally indoors and outdoors the most likely to be remembered followed by mainly indoor dogs, with mostly outdoor dogs the least likely to be remembered (both χ2 P < 0.05, data not shown).

For all analyses, cat and dog ownership is reported by using dichotomized groupings (any cats or dogs vs. none) but was also assessed as 0, 1, or 2 or more animals (data not shown). These results did not vary from those for the dichotomized groupings; therefore, the dichotomized groupings were chosen for ease of presentation. In addition, for each analysis, ownership of indoor animals was separately tested, and these results did not vary from those for total animal ownership. To minimize misclassification error, data on indoor and outdoor animals were combined in the reported analyses.

DISCUSSION

This investigation into teen recall of childhood pet ownership found that teens correctly reported early (birth–age 6 years) childhood cats and dogs 86.3% and 79.2% of the time, respectively. In addition, teens were more likely to underestimate than overestimate the number of pets in their home. Recall of cats and dogs was on average “moderate” (kappa statistic = 0.41–0.60) (10) and at times achieved “substantial” agreement (0.61–0.80) for female respondents and those without dogs or cats at age 18 years. Current dog owners were less likely to recall their childhood dogs 5 of the 6 years assessed as compared with teens without a dog in the home, while current cat owners were less likely than teens without a cat in the home to recall their cats from 2 of the 6 years assessed.

Pet recall did not vary significantly by reported symptoms around cats or dogs or by year of life, but there was a positive, significant trend in overreport of cats and dogs by teens with increasing year of childhood (P < 0.001). Amount of time the pets spent indoors was largely unrelated to teen recall of the animal, with the exception of recall of dogs for 2 of the 6 years assessed. Finally, those with a history of physician-diagnosed asthma more accurately reported their cats from the fifth year of life than those lacking a diagnosis.

One other article on recall of childhood pets was identified in the literature. Svanes et al. (8) reported substantial agreement between adults asked about their childhood pets on 2 separate occasions 9 years apart. However, this group asked participants about pet keeping as “a child” without defining specific ages when pets were kept and conducted no prospective evaluation of pets in childhood. Therefore, we cannot directly compare our findings with theirs.

Unlike Svanes et al. (7, 8), we did not use immunoglobulin E to further classify our participants. Although positive specific immunoglobulin E is frequently used to dichotomize people as allergic or not allergic, differential reporting of childhood pets may be more likely if one recognizes and reports symptoms rather than relying on specific immunoglobulin E levels that may not be associated with symptoms and would largely be unknown to the participant. Those who have or have ever had asthma symptoms around animals may be more inclined to remember their childhood pets, especially if pets triggered their asthma symptoms or if their family intentionally did not keep pets because of the child's asthma.

Pet characteristics, including numbers of pets in the home, affect household levels of pet allergen and biomarkers of bacterial load such as endotoxin (12–14); therefore, when assessing disease outcomes, these variables merit evaluation. With an estimated 37.2% of households in the United States owning a dog and 32.4% owning a cat (an average of 1.7 dogs and 2.2 cats, respectively, in these homes) (15), detailed questions regarding cat and dog ownership during childhood are warranted. Even though our research focused on allergic disease, recall of childhood pets may be applicable elsewhere.

Some limitations of our analysis are that pet reporting at the time of pet ownership was completed by the parent of the teen and not the teen himself or herself; however, prospective data collection on infants requires report by others. We focused on accuracy of teen report of his or her household pet exposure during the first 6 years of life—a time when he or she is likely to have limited recall.

It is possible that pets residing in the home for longer periods of time during childhood were more accurately remembered by teens than were pets in the home for shorter periods of time, or that pets allowed in the child's bedroom or those having more daily interaction with the child would be more likely to be remembered by teens. Unfortunately, we are unable to address these issues because these data were not collected during childhood.

Furthermore, racial/ethnic diversity of this cohort is limited and varies from the national averages, so this factor may limit application of our findings to the general population. However, the study population was homogenous with respect to race/ethnicity and provided a good sample size for our analyses.

Our findings suggest good accuracy during young adulthood of pet reporting for ages 0–6 years but that childhood pet recall may vary depending on the sex of the participant and the health outcome of interest. This variance may impact the results of epidemiologic studies that rely on retrospective evaluation of childhood pet exposure.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Biostatistics and Research Epidemiology, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan (Charlotte Nicholas, Ganesa Wegienka, Suzanne Havstad, Christine Cole Johnson); Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Michigan (Edward Zoratti); and Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, Georgia (Dennis Ownby).

Funding was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The authors thank the Childhood Allergy Study families for their continued participation in this study as well as the Childhood Allergy Study interviewers and clinic and laboratory staff for their dedication to this project.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Aichbhaumik N, Zoratti EM, Strickler R, et al. Prenatal exposure to household pets influences fetal immunoglobulin E production. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(11):1787–1794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remes ST, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, et al. Dog exposure in infancy decreases the subsequent risk of frequent wheeze but not of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(4):509–515. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perzanowski MS, Chew GL, Divjan A, et al. Cat ownership is a risk factor for the development of anti-cat IgE but not current wheeze at age 5 years in an inner-city cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(4):1047–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radon K, Windstetter D, Poluda AL, et al. Contact with farm animals in early life and juvenile inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):354–361. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swensen AR, Ross JA, Shu XO, et al. Pet ownership and childhood acute leukemia (USA and Canada) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(4):301–303. doi: 10.1023/a:1011276417369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Meer G, Toelle BG, Ng K, et al. Presence and timing of cat ownership by age 18 and the effect on atopy and asthma at age 28. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(3):433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svanes C, Heinrich J, Jarvis D, et al. Pet-keeping in childhood and adult asthma and hay fever: European Community Respiratory Health Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(2):289–300. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Svanes C, Dharmage S, Sunyer J, et al. Long-term reliability in reporting of childhood pets by adults interviewed twice, 9 years apart. Results from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey I and II. Indoor Air. 2008;18(2):84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2008.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ownby DR, Johnson CC, Peterson EL. Maternal smoking does not influence cord serum IgE or IgD concentrations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;88(4):555–560. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90148-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas C, Wegienka G, Havstad S, et al. Influence of cat characteristics on Fel d 1 levels in the home. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(1):47–50. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60834-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arbes SJ, Jr, Cohn RD, Yin M, et al. Dog allergen (Can f 1) and cat allergen (Fel d 1) in US homes: results from the National Survey of Lead and Allergens in Housing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(1):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bufford JD, Reardon CL, Li Z, et al. Effects of dog ownership in early childhood on immune development and atopic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(10):1635–1643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Veterinary Medical Association. U.S. Pet Ownership & Demographics Sourcebook. 2007. ( http://www.avma.org/reference/marketstats/ownership.asp). (Accessed October 3, 2008) [Google Scholar]