Abstract

Many epidemiologic studies include symptom checklists assessing recall of symptoms over a specified time period. Little research exists regarding the congruence of short-term symptom recall with daily self-reporting. The authors assessed the sensitivity and specificity of retrospective reporting of vasomotor symptoms using data from 567 participants in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (1997–2002). Daily assessments were considered the “gold standard” for comparison with retrospective vasomotor symptom reporting. Logistic regression was used to identify predictors of sensitivity and specificity for retrospective reporting of any vasomotor symptoms versus none in the past 2 weeks. Sensitivity and specificity were relatively constant over a 3-year period. Sensitivity ranged from 78% to 84% and specificity from 85% to 89%. Sensitivity was lower among women with fewer symptomatic days in the daily assessments and higher among women reporting vasomotor symptoms in the daily assessment on the day of retrospective reporting. Specificity was negatively associated with general symptom awareness and past smoking and was positively associated with routine physical activity and Japanese ethnicity. Because many investigators rely on symptom recall, it is important to evaluate reporting accuracy, which was relatively high for vasomotor symptoms in this study. The approach presented here would be useful for examining other symptoms or behaviors.

Keywords: data collection, hot flashes, mental recall, sensitivity and specificity, sweating, vasomotor system

Many epidemiologic studies collecting self-reported symptom data rely on retrospective reporting, with typical recall intervals of 2 weeks or 1 month (1–10). Daily reporting is likely to be more accurate because it requires less recall (11–14), but it is more logistically difficult. Little research has focused on the congruence of retrospective and daily self-reporting.

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) (15) is one of the few studies to employ multiple measurement frequencies simultaneously. Utilizing data from SWAN, we compared retrospective reporting of any (versus no) vasomotor symptoms—hot flashes and night sweats—in the past 2 weeks from end-of-month surveys with daily reporting carried out during the same interval. Using as the standard any (versus no) vasomotor symptoms in the past 2 weeks based on daily reporting, we estimated sensitivity and specificity for retrospective reporting and identified correlates of sensitivity and specificity. We hypothesized that sensitivity would increase with frequency of vasomotor symptoms—and thus would be positively related to correlates of vasomotor symptoms—and that both sensitivity and specificity would be related to characteristics typically associated with accuracy of self-reporting, such as education.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

Details of SWAN's study design and recruitment have been reported previously (15). Briefly, SWAN includes 7 US sites: Boston, Massachusetts; Chicago, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; Los Angeles, California; Newark, New Jersey; Oakland, California; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At each site, approximately 430 participants, including non-Hispanic Caucasian women and women from 1 other minority group (African-American, Chinese, Hispanic, or Japanese), were recruited. Eligibility criteria included: being aged 42–52 years; having an intact uterus and at least 1 ovary; having had at least 1 menstrual period and no use of sex steroid hormones in the previous 3 months; not being pregnant or breastfeeding; being able to speak English or another designated language (Spanish, Cantonese, or Japanese); and self-identification with one of the site's 2 designated racial/ethnic groups. During eligibility screening in 1995–1997, a total of 6,517 women met these criteria, and 3,302 women (50.7%) enrolled. The study was approved by each participating institution's review board, and all participants gave informed consent.

At the first annual follow-up, a subcohort of 880 women was recruited into the Daily Hormone Study (DHS), with oversampling of non-Caucasians. Enrollment criteria were the same as those for the parent study, with participants being approximately 1 year older than at baseline. Each year, DHS participants collected first-morning voided urine for an entire menstrual cycle (up to 50 days), concurrently with completion of a daily symptom diary. All SWAN participants also recorded symptoms experienced during the past 2 weeks in an end-of-month survey. The results presented here include data from the first 3 annual DHS collections, which occurred in 1997–2002. To be included, a 2-week interval of vasomotor symptom reporting from the end-of-month survey had to overlap completely with 2 weeks of DHS daily diaries, with no symptom data being missing from either instrument.

Measures

In the end-of-month survey, participants recorded whether in the past 2 weeks they had experienced any hot flashes or flushes and any night sweats. Participants also recorded on a daily basis the occurrence of any hot flashes/night sweats (i.e., combined) in the past 24 hours. For comparability, both reports were collapsed to indicate any hot flashes or night sweats in the past 2 weeks.

Candidate predictors of sensitivity and specificity included those hypothesized to be related to vasomotor symptoms or to reporting accuracy (16–21). Unless specified otherwise, time-varying information was from the annual study visit preceding the DHS collection. Age was computed from birth date and the end date of the 2-week reporting interval. Educational level and financial strain were measured at baseline. Baseline acculturation was defined as an acculturation score related to preferred language for reading, speaking, thinking, and radio/television programs (22). Baseline smoking was assessed with questions from the American Thoracic Society (23). Body mass index was computed as measured weight (kg) divided by the square of measured height (m). Physical activity was assessed from questions adapted from the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey, based on the Baecke physical activity questionnaire (24–26). General symptom awareness was measured at the first annual follow-up visit using the Somatasensory Amplification Scale (27)—the summed score of the degree of awareness of loud noise, hot or cold, hunger, pain, and things happening in one's body, with responses for each item ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely true). Depressive symptoms were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, which assessed the extent to which each symptom had been experienced in the previous week (28). Sleep difficulty was defined as the number of the following symptoms occurring at least 3 times per week in the past 2 weeks: trouble falling asleep, waking up several times per night, and waking up earlier than planned and being unable to fall asleep again (29, 30).

Menopausal status was defined as “late reproductive” if menses had occurred in the past 3 months with no decrease in regularity, “early menopausal transition” if menses had occurred in the past 3 months with decreased regularity, “late menopausal transition” if the last menstrual period had occurred more than 3 months ago but fewer than 12 months ago, and “postmenopausal” if the last menstrual period had occurred at least 12 months ago without another cause (31–36). These definitions are similar to but not identical to the definitions proposed in recent studies such as the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (34) or the studies by Harlow et al. (35, 36), which were published several years after SWAN data collection began; the definitions used here were based on criteria available before the start of SWAN in 1995 (e.g., World Health Organization criteria) (31–33). For measurement of estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone levels, blood was drawn annually on days 2–5 (days 2–7 from January 1, 1996, through May 30, 1996) of the menstrual cycle for regularly cycling participants and on a random day within 90 days of the annual visit for others.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics at the first DHS visit were summarized using frequencies, means, and standard deviations. Sensitivity and specificity for retrospective reporting, treating 2-week occurrence of any vasomotor symptoms from daily reporting as the standard, were computed at each visit; sensitivity also was computed by the number of days with vasomotor symptoms entered in the daily diaries. Combining data across the 3 annual visits, random-effects logistic regression models (37) were fitted for retrospective reporting of any vasomotor symptoms (a positive match, i.e., true positive vs. false negative) in the subset of participants with any vasomotor symptoms in the daily diaries, and separate models were fitted for retrospective reporting of no vasomotor symptoms (a negative match, i.e., true negative vs. false positive) in the subset with no vasomotor symptoms in the daily diaries, to identify factors related to sensitivity and specificity, respectively. All hypothesis tests were 2-sided.

RESULTS

Of the 880 DHS participants, 313 provided no usable observations for these analyses—that is, no collections with complete overlap of the 2-week reporting interval and no missing symptom data. The remaining 567 participants provided 1–3 observations (mean = 1.5) for these analyses. At the first round of DHS data collection, 363 women had incomplete overlap of the 2-week reporting interval and another 194 had missing symptom data, for a total sample size of 323 at the first round. Reflecting the study design, these 323 participants were predominantly premenopausal or early perimenopausal at the first round of data collection (Table 1), and approximately one-third were Caucasian. Most had at least some college and were highly acculturated. Few were current smokers, and more than half were overweight or obese.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample at Baseline (n = 323), Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, 1997–1999

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % | Range |

| Mean no. of days with vasomotor symptoms in daily diaries | 2.1 (3.9) | 0–14 |

| No. of days with vasomotor symptoms in daily diaries, % | ||

| 0 | 60.1 | |

| 1–2 | 16.3 | |

| 3–5 | 9.7 | |

| ≥6 | 13.9 | |

| Vasomotor symptoms on last day of 14-day interval, % | 19.5 | |

| Mean age, years | 47.4 (2.6) | 43.0–53.5 |

| Ethnicity, % | ||

| African-American | 20.4 | |

| Caucasian | 33.1 | |

| Chinese | 18.6 | |

| Hispanic | 5.9 | |

| Japanese | 22.0 | |

| Education, % | ||

| Less than high school completion | 7.1 | |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 18.9 | |

| Some college | 31.0 | |

| College degree | 21.4 | |

| Postcollege studies | 21.7 | |

| Difficulty paying for basics, % | ||

| Very hard | 6.2 | |

| Somewhat hard | 28.8 | |

| Not at all hard | 65.0 | |

| Acculturation, % | ||

| Low | 16.1 | |

| Medium | 10.2 | |

| High | 73.7 | |

| Smoking status, % | ||

| Never smoker | 68.9 | |

| Past smoker | 21.4 | |

| Current smoker | 9.6 | |

| Mean body mass indexa | 27.0 (6.6) | 16.7–52.9 |

| Body mass index, % | ||

| Underweight/normal (<25) | 47.5 | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 25.5 | |

| Obese (≥30) | 27.0 | |

| Mean physical activity domain scores (possible range, 1–5) | ||

| Routine activity | 2.4 (0.8) | 1–5 |

| Sports activity | 2.6 (1.1) | 1–4.8 |

| Household/caregiving activity | 2.7 (0.8) | 1–5 |

| Mean symptom awareness score (possible range, 5–25) | 15.1 (3.6) | 5–24 |

| Mean CES-D score (possible range, 0–60) | 8.5 (7.9) | 0–48 |

| Mean no. of sleep difficulties occurring ≥3 times/week in past 2 weeks (possible range, 0–3) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0–3 |

| Menopausal status, % | ||

| Premenopausal | 25.4 | |

| Early perimenopausal | 74.3 | |

| Late perimenopausal | 0.3 | |

| Mean estradiol level (pg/mL) | 72.3 (72.3) | 9.7–521.2 |

| Mean follicle-stimulating hormone level (mIU/mL) | 26.8 (24.2) | 1.7–196.7 |

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression [Scale]; SD, standard deviation.

Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Observations excluded because of incomplete overlap of the 2-week reporting interval differed from the analytic sample only in terms of shorter urine collections due to a shorter menstrual cycle. Compared with the analytic sample, women excluded at baseline because of missing data were more likely to be African-American or Hispanic and had lower socioeconomic status, lower acculturation, a lower estradiol level, more depressive symptoms, more anxiety, lower sports-related activity, and a higher body mass index. Differences in factors other than race/ethnicity reflected confounding by race/ethnicity, with the exception of estradiol. To assess the impact of missing symptom data, we carried out the analyses again after interpolating missing symptom data based on reports made before and after a gap; resulting estimates of sensitivity and specificity using complete and imputed data combined were similar (results not shown) to those presented here for women with complete data.

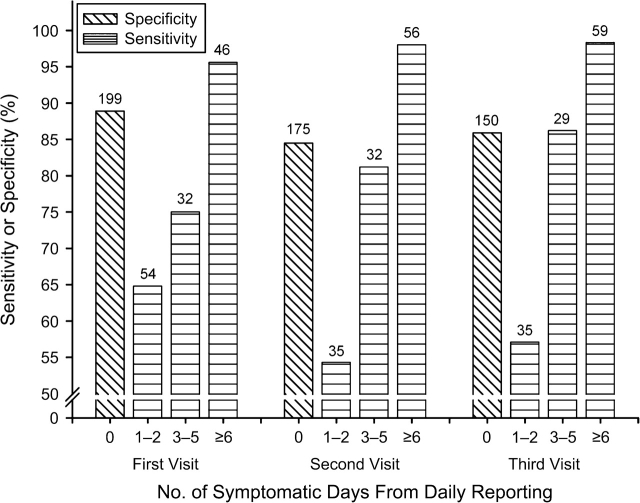

Sensitivity and specificity (Figure 1) were fairly constant across the 3 annual visits. Overall sensitivity, ranging from 78% to 84%, was lower than specificity (85%–89%). Sensitivity was lower in women with fewer symptomatic days reported in the daily diaries; that is, greater underreporting occurred in participants with less frequent symptoms.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity and specificity of retrospective reporting of vasomotor symptoms at each annual study visit, by number of symptomatic days from daily symptom reporting, Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, 1997–2002. Overall sensitivity was 77.8% at the first visit, 80.6% at the second visit, and 83.5% at the third visit. Numbers at the top of each bar indicate the number of observations.

In separate univariate logistic regression analyses conducted for each candidate predictor, few predictors of sensitivity or specificity emerged. The strongest predictor of sensitivity (Table 2) was number of symptomatic days in the daily diaries, with an odds ratio for a positive match of 19.87 for 6 or more symptomatic days as compared with 1–2 symptomatic days. Similarly, sensitivity was higher among women reporting vasomotor symptoms in the daily diary on the day of retrospective 2-week reporting in the end-of-month survey. Specificity was negatively associated with general symptom awareness; that is, overreporting was more common among women with higher symptom awareness and was positively associated with routine physical activity but not sports or household physical activity. Past smokers, but not current smokers, had lower specificity—greater overreporting—than never smokers. Japanese women had the highest specificity. Associations were similar in multivariate analyses that included all of the variables in Table 2 (results not shown).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Positive and Negative Matches of Retrospective Reporting With Daily Symptom Reporting of Any (Versus No) Vasomotor Symptoms in a 2-Week Interval (Individual Random-Effects Logistic Regression Analyses), Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, 1997–2002

| Characteristic | Positive Match of Retrospective Reporting With Daily Reporting (354 Observations From 264 Women) |

Negative Match of Retrospective Reporting With Daily Reporting (491 Observations From 353 Women) |

||||

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| No. of days with vasomotor symptoms in daily diaries | <0.0001 | |||||

| 1–2 | Reference | |||||

| 3–5 | 2.61 | 1.31, 5.22 | ||||

| ≥6 | 19.87 | 7.31, 54.03 | ||||

| Vasomotor symptoms recorded in daily diary on last day of 2-week interval | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | Reference | |||||

| Yes | 6.51 | 3.18, 13.32 | ||||

| Age (1-year increase) | 1.11 | 1.00, 1.24 | 0.06 | 1.03 | 0.93, 1.15 | 0.53 |

| Ethnicity | 0.20 | 0.07 | ||||

| Caucasian | Reference | Reference | ||||

| African-American | 2.15 | 0.97, 4.77 | 0.92 | 0.41, 2.05 | ||

| Chinese | 1.11 | 0.46, 2.68 | 1.67 | 0.75, 3.70 | ||

| Hispanic | 2.74 | 0.54, 13.76 | 0.81 | 0.21, 3.08 | ||

| Japanese | 1.98 | 0.88, 4.43 | 3.20 | 1.30, 7.85 | ||

| Education | 0.45 | 0.25 | ||||

| Less than high school completion | 0.45 | 0.14, 1.46 | 0.55 | 0.15, 2.06 | ||

| High school diploma or equivalent | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Some college | 1.26 | 0.55, 2.87 | 0.67 | 0.28, 1.57 | ||

| College degree | 1.12 | 0.43, 2.95 | 1.59 | 0.58, 4.33 | ||

| Postcollege studies | 0.86 | 0.35, 2.13 | 1.08 | 0.40, 2.91 | ||

| Difficulty paying for basics | 0.22 | 0.20 | ||||

| Very hard | 0.50 | 0.18, 1.39 | 0.70 | 0.20, 2.44 | ||

| Somewhat hard | 1.31 | 0.68, 2.50 | 0.57 | 0.31, 1.06 | ||

| Not at all hard | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Acculturation | 0.83 | 0.93 | ||||

| Low | 1.03 | 0.49, 2.16 | 1.03 | 0.46, 2.33 | ||

| Medium | 1.45 | 0.43, 4.82 | 1.18 | 0.49, 2.82 | ||

| High | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Smoking status | 0.27 | 0.03 | ||||

| Never smoker | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Past smoker | 0.94 | 0.50, 1.77 | 0.51 | 0.26, 0.99 | ||

| Current smoker | 2.43 | 0.77, 7.62 | 3.12 | 0.69, 14.11 | ||

| Body mass indexa | 0.83 | 0.13 | ||||

| Underweight/normal (<25) | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 1.22 | 0.58, 2.58 | 0.66 | 0.32, 1.35 | ||

| Obese (≥30) | 0.99 | 0.51, 1.91 | 0.51 | 0.26, 1.00 | ||

| Physical activity domain scores (1-unit increase) | ||||||

| Routine activity | 0.93 | 0.65, 1.31 | 0.66 | 1.69 | 1.11, 2.57 | 0.01 |

| Sports activity | 0.92 | 0.70, 1.21 | 0.53 | 1.16 | 0.87, 1.55 | 0.32 |

| Household/caregiving activity | 0.96 | 0.69, 1.36 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.60, 1.21 | 0.38 |

| Symptom awareness score (1-unit increase) | 1.00 | 0.92, 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.81, 0.96 | 0.004 |

| CES-D score (1-unit increase) | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.96, 1.02 | 0.53 |

| No. of sleep difficulties occurring ≥3 times/week in past 2 weeks (1-unit increase) | 1.02 | 0.75, 1.39 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.60, 1.32 | 0.06 |

| Menopausal status | 0.25 | 0.98 | ||||

| Late reproductive | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Early transition | 1.28 | 0.56, 2.89 | 1.01 | 0.50, 2.01 | ||

| Late transition/postmenopausal | 2.60 | 0.81, 8.38 | 0.89 | 0.25, 3.2 | ||

| Log estradiol levelb | 0.73 | 0.51, 1.02 | 0.07 | 1.06 | 0.72, 1.55 | 0.78 |

| Log follicle-stimulating hormone levelb | 1.34 | 0.94, 1.91 | 0.11 | 1.29 | 0.87, 1.91 | 0.21 |

Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression [Scale]; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

Odds ratios were computed for the difference between the 75th percentile and the 25th percentile and were adjusted for day of the menstrual cycle.

DISCUSSION

Both sensitivity and specificity for retrospectively reported vasomotor symptoms in the past 2 weeks were high (78%–89%), similar to findings regarding recall of hormone therapy (38). Accuracy of retrospective reporting was strongly associated with the number of symptomatic days in daily diaries. Women at either extreme—0 or ≥6 symptomatic days in the past 2 weeks—had the highest probability of accurate retrospective reporting, perhaps because these extremes are easier to recall (39). Extreme occurrences are more accurately recalled in other contexts as well, including heavier menstrual bleeding (40) and skipped menstrual periods (41) in studies of menstrual cycling, injurious falls versus noninjurious falls among elders (42), and vigorous rather than moderate physical activity (43–45). Because frequency of vasomotor symptoms has been positively related to severity (46), these results also suggest that women with milder vasomotor symptoms are more likely to underreport retrospectively recalled symptoms.

The higher sensitivity among women with vasomotor symptoms on the day of retrospective reporting is consistent with prior findings that recall of past symptoms is affected by current symptoms (47–52). Higher symptom awareness was associated with overreporting, reflecting the impact of symptom salience on memory (39, 53).

Japanese participants had the highest specificity, as well as lower rates of missing symptom data, suggesting greater general compliance with the study protocol. The lower specificity in past smokers but not current smokers as compared with never smokers may be a spurious finding due to the relatively small number of current smokers. The association of specificity with routine physical activity but not other domains may be due to chance, given the number of statistical comparisons.

One limitation of the study was that by necessity, comparisons of retrospective and daily reporting were restricted to women recording symptoms on a daily basis for at least 13 days prior to the end-of-month report, who thus may have been sensitized to symptom occurrence (or nonoccurrence) (38, 54). The relatively short recall period also may have contributed to increased accuracy (55), as seen for recall of occurrences such as menstrual bleeding (56) and sexual activity (57, 58). A 2-week recall period is frequently used, however, and thus these results are likely to be applicable to many studies of vasomotor symptoms.

In addition, women excluded because of missing data were more likely to have characteristics associated with lower accuracy of reporting. Consequently, estimates of sensitivity and specificity may be inflated in comparison with the general population. However, results including imputations of missing symptom data were similar to those presented here. Moreover, sensitivity and specificity did not differ significantly for women with observed symptom data and women with missing (imputed) symptom data. The odds of a negative match were 1.39 times higher (95% confidence interval: 0.88, 2.20) for women with observed symptom data than for women with imputed symptom data, and the corresponding odds ratio for a positive match was 1.34 (95% confidence interval: 0.82, 2.20).

Other limitations include the lack of measured daily frequency, intensity, or bothersomeness. In addition, because only 23 women had less than a high school education, we had relatively low power to detect a difference between this group and persons with higher levels of educational attainment regarding sensitivity and specificity. No gradient was observed across the higher educational categories, however.

The strengths of this study included the availability of a large and diverse community-based sample with extensive covariate information. The wealth of study data provided a rare opportunity to assess the congruence of retrospective 2-week symptom recall with concurrent daily reporting.

Limiting recruitment to women with frequent or bothersome symptoms, despite the greater accuracy in their symptom measurement, would preclude a description of the full range of women's symptom experiences and decrease the ability to identify correlates or sequelae of symptoms by decreasing sample variability (59). To reduce underreporting without drastically increasing participant burden, more frequent self-reports (e.g., daily reporting over a short interval) could be substituted for retrospective recall, as in the SWAN DHS or the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study (60). Alternatively, analyses of retrospective reports could collapse “asymptomatic” and “low frequency” subgroups, since the former may include some participants with truly low symptom frequencies. Similarly, given the previously observed correspondence between symptom frequency and severity (46), “asymptomatic” and “mild symptoms” subgroups could be combined in analyses of symptom severity. Accounting in statistical analyses for symptom awareness and occurrence of symptoms on the day of retrospective recall also would be beneficial (49).

Undoubtedly, researchers will continue to rely on retrospective symptom reporting, particularly in large epidemiologic studies. Thus, it is important to improve measurement. Sensitivity and specificity and their correlates may vary across symptoms or behaviors. For example, social desirability may account in part for underreporting of heavy alcohol consumption (61–64) or overestimation of physical activity in participants with higher body mass index (43). The approach illustrated here, however, would be useful for examining accuracy of retrospective reporting for a variety of health-related factors.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Medicine, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts (Sybil L. Crawford, Jennifer Kelsey); Division of Public Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Nancy E. Avis); Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California at Davis, Davis, California (Ellen Gold); Department of Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Janet Johnston); Department of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Women's Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, New York (Nanette Santoro); Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (MaryFran Sowers); and Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, California (Barbara Sternfeld).

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Nursing Research, and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (grants NR004061, AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, and AG012495).

The authors thank Drs. Katherine Newton and Vered Stearns for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

SWAN Clinical Centers: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan—MaryFran Sowers, Principal Investigator; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts—Robert Neer, Principal Investigator, 1994–1999; Joel Finkelstein, Principal Investigator, 1999–present; Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois—Lynda Powell, Principal Investigator; University of California, Davis, California/Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, California—Ellen Gold, Principal Investigator; University of California, Los Angeles, California—Gail Greendale, Principal Investigator; University of Medicine and Dentistry–New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey—Gerson Weiss, Principal Investigator, 1994–2004; Nanette Santoro, Principal Investigator, 2004–present; University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—Karen Matthews, Principal Investigator. NIH Program Office: National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, Maryland—Marcia Ory, 1994–2001; Sherry Sherman, 1994–present; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, Maryland—Program Officers. Central Laboratory: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan—Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). Coordinating Center: New England Research Institutes, Watertown, Massachusetts—Sonja McKinlay, Principal Investigator, 1995–2001; University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, Principal Investigator, 2001–present. Steering Committee: Chris Gallagher, Chair; Susan Johnson, Chair.

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health, or the NIH.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DHS

Daily Hormone Study

- SWAN

Study of Women's Health Across the Nation

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botman SL, Moore TF, Moriarty CL, et al. Design and Estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1995–2004. (Vital and Health Statistics, series 2, no. 130) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Colvin A. A universal menopausal syndrome? Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuh DL, Wadsworth M, Hardy R. Women's health in midlife: the influence of the menopause, social factors and health in earlier life. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104(8):923–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb14352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennerstein L, Smith AM, Morse CA, et al. Menopausal symptoms in Australian women. Med J Aust. 1993;159(4):232–236. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinlay S, McKinlay J, Brambilla D. The relative contributions of endocrine changes and social circumstances to depression in mid-aged women. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28(4):345–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obermeyer CM, Reynolds RF, Price K, et al. Therapeutic decisions for menopause: results of the DAMES project in central Massachusetts. Menopause. 2004;11(4):456–465. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000109318.11228.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Wing RR, et al. Prior to use of estrogen replacement therapy, are users healthier than non-users? Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(10):971–978. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews KA, Bromberger JT. Does the menopausal transition affect health-related quality of life? Am J Med. 2005;118(suppl 12B):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawber TR, Kannel WB, Lyell L. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: The Framingham Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1963;107:539–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb13299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCoy NL. Methodological problems in the study of sexuality and the menopause. Maturitas. 1998;29(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snowden R. The statistical analysis of menstrual bleeding patterns. J Biosoc Sci. 1977;9(1):107–120. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bean JA, Leeper JD, Wallace RB, et al. Variations in the reporting of menstrual histories. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):181–185. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufert PA, Gilbert P, Hassard T. Researching the symptoms of menopause: an exercise in methodology. Maturitas. 1988;10(2):117–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(88)90156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sowers M, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, et al. Design, survey, sampling and recruitment methods of SWAN: a multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc; 2000. pp. 175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronenberg F. Hot flashes: epidemiology and physiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;592:52–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avis NE, Crawford SL, McKinlay SM. Psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors related to menopause symptomatology. Womens Health. 1997;3(2):103–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avis NE, Kaufert PA, Lock M, et al. The evolution of menopausal symptoms. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;7(1):17–32. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold EB. Demographics, environmental influences, and ethnic and international differences in the menopausal experience. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, editors. Menopause: Biology and Pathobiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc; 2000. pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40–55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(5):463–473. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford SL. The roles of biologic and non-biologic factors in cultural differences in vasomotor reporting measured by surveys. Menopause. 2007;14(4):725–733. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31802efbb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marín G, Sabogal F, Marín BV, et al. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(6):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sternfeld B, Ainsworth BA, Quesenberry CP., Jr Physical activity patterns in a diverse population of women. Prev Med. 1999;28(3):313–323. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sternfeld B, Wang H, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. Physical activity and changes in weight and waist circumference in midlife women: findings from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(9):912–922. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baecke JAH, Burema J, Fritjers JER. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36(95):936–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barsky AJ, Goodson JD, Lane RS, et al. The amplification of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1988;50(5):510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27(8):1567–1596. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Taylor DJ, et al. Quantitative criteria for insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(4):427–445. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brambilla DJ, McKinlay SM, Johannes CB. Defining the perimenopause for application in epidemiologic investigations. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(12):1091–1095. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Taffe J, et al. Using longitudinal data to define the perimenopause by menstrual cycle characteristics. Climacteric. 1998;1(1):18–25. doi: 10.3109/13697139809080677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization Scientific Group. Research on Menopause in the 1990s. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. (WHO Technical Report Series no. 866) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Fertil Steril. 2001;76(5):874–878. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harlow SD, Cain K, Crawford S, et al. Evaluation of four proposed bleeding criteria for the onset of late menopausal transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(9):3432–3438. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harlow SD, Mitchell ES, Crawford S, et al. The ReSTAGE Collaboration: defining optimal bleeding criteria for onset of early menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(1):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molenberghs G, Verbeke G. Models for Discrete Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Springer Science; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merlo J, Berglund G, Wirfält E, et al. Self-administered questionnaire compared with a personal diary for assessment of current use of hormone therapy: an analysis of 16,060 women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(8):788–792. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.8.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warnecke RB, Johnson TP, Chávez N, et al. Improving question wording in surveys of culturally diverse populations. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(5):334–342. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mansfield PK, Voda A, Allison G. Validating a pencil-and-paper measure of perimenopausal blood loss. Womens Health Issues. 2004;14(6):242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith-DiJulio K, Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Concordance of retrospective and prospective reporting of menstrual irregularity by women in the menopausal transition. Climacteric. 2005;8(4):390–397. doi: 10.1080/13697130500345018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganz DA, Higashi T, Rubenstein LZ. Monitoring falls in cohort studies of community-dwelling older people: effect of the recall interval. Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2190–2194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irwin ML, Ainsworth BE, Conway JM. Estimation of energy expenditure from physical activity measures: determinants of accuracy. Obesity Res. 2001;9(9):517–525. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(1):91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilcox S, Irwin ML, Addy C, et al. Agreement between participant-rated and compendium-coded intensity of daily activities in a triethnic sample of women ages 40 years and older. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(4):253–262. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, et al. Methodlogic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(23):4280–4290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eich E, Reeves JL, Jaeger B, et al. Memory for pain: relation between past and present pain intensity. Pain. 1985;23(4):375–379. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross M, Olson JM. An expectancy-attribution model of the effects of placebos. Psychol Rev. 1981;88(5):408–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meek PM, Lareau SC, Anderson D. Memory for symptoms in COPD patients: how accurate are their reports? Eur Respir J. 2001;18(3):474–481. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00083501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miranda H, Gold JE, Gore R, et al. Recall of prior musculoskeletal pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):294–299. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wells JE, Horwood LJ. How accurate is recall of key symptoms of depression? A comparison of recall and longitudinal reports. Psychol Med. 2004;34(6):1001–1011. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harvey AG, Bryant RA. Memory for acute stress disorder symptoms: a two-year prospective study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(9):602–607. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mesulam MM. From sensation to cognition. Brain. 1998;121(6):1013–1052. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basilicato S, Groves M, Nisbet L, et al. Effect of concurrent chest pain assessment on retrospective reports by cardiac patients. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1992;7(1):56–67. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koren G, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, et al. Recall bias of the symptoms of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):485–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wegienka G, Bard DD. A comparison of recalled date of last menstrual period with prospectively recorded dates. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14(3):248–252. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graham CA, Catania JA, Brand R, et al. Recalling sexual behavior: a methodological analysis of memory recall bias via interview using the diary as the gold standard. J Sex Res. 2003;40(4):325–332. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kauth MR, Lawrence JS, Kelly JA. Reliability of retrospective assessments of sexual HIV risk behavior: a comparison of biweekly, three-month, and twelve-month reports. AIDS Educ Prev. 1991;3(3):207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weisberg S. Applied Linear Regression. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitchell ES, Woods NF. Symptom experiences of midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. Maturitas. 1996;25(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(96)01047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hilton ME. A comparison of a prospective diary and two summary recall techniques for recording alcohol consumption. Br J Addict. 1989;84(9):1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leigh BC, Gillmore MR, Morrison DM. Comparison of diary and retrospective measures for recording alcohol consumption and sexual activity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(2):119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Townshend JM, Duka T. Patterns of alcohol drinking in a population of young social drinkers: a comparison of questionnaire and diary measures. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(2):187–192. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitty C, Jones RJ. A comparison of prospective and retrospective diary methods of assessing alcohol use among university undergraduates. J Public Health Med. 1992;14(3):264–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]