Abstract

Small babies from a population with higher infant mortality often have better survival than small babies from a lower-risk population. This phenomenon can in principle be explained entirely by the presence of unmeasured confounding factors that increase mortality and decrease birth weight. Using a previously developed model for birth weight-specific mortality, the authors demonstrate specifically how strong unmeasured confounders can cause mortality curves stratified by known risk factors to intersect. In this model, the addition of a simple exposure (one that reduces birth weight and independently increases mortality) will produce the familiar reversal of risk among small babies. Furthermore, the model explicitly shows how the mix of high- and low-risk babies within a given stratum of birth weight produces lower mortality for high-risk babies at low birth weights. If unmeasured confounders are, in fact, responsible for the intersection of weight-specific mortality curves, then they must also (by virtue of being confounders) contribute to the strength of the observed gradient of mortality by birth weight. It follows that the true gradient of mortality with birth weight would be weaker than what is observed, if indeed there is any true gradient at all.

Keywords: birth weight, confounding factors (epidemiology), infant mortality, smoking

Birth weight is a powerful predictor of infant mortality, although whether birth weight itself is causally related to survival is subject to debate (1–8). The strong gradient of mortality at lower weights, seen even among babies born at term (1), could suggest a causal role of birth weight. On the other hand, the observation that small babies from a population with lower weights usually have better survival than small babies from a heavier population is not what one would predict if birth weight were a simple cause of mortality. Sometimes called the “pediatric” or “low birth weight paradox,” this phenomenon has been widely discussed (2, 3, 5, 9–16). A well-known example is the comparison of babies of smokers and nonsmokers. Infants of smokers weigh less on average than babies of nonsmokers and have higher infant mortality. However, at low birth weights, babies of smokers have lower mortality than infants of nonsmokers. Smoking has many effects on pregnancy, beyond that of decreasing birth weight and increasing perinatal mortality. It is not known how much (if any) of the smoking effect on mortality operates through birth weight (11, 12). If a hypothetical intervention could specifically erase only the effect of smoking on birth weight, any resulting improvement in mortality would be evidence of a causal effect of birth weight on mortality.

The phenomenon of intersecting mortality curves is perplexing only if we assume that, after removing known confounders, the whole gradient of mortality with decreasing birth weight is causal. Unmeasured confounding can, as previously argued (3, 15, 16), explain why mortality curves intersect. Strong unmeasured confounders can, at least in theory, also fully explain the gradient of mortality with birth weight (1). In this paper, we show that the strong unmeasured confounders that we have previously proposed can produce intersecting mortality curves. Our calculations explicitly demonstrate how confounding produces a mix of high- and low-risk babies that changes with birth weight and how this mix also produces changes in relative mortality across the spectrum of birth weight.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Assumptions

We use a previously described model (1) based on the following assumptions:

Each baby has a “target” birth weight (i.e., the weight the baby would ideally have if no factor intervenes to modify it).

Target birth weights have a Gaussian distribution.

Target birth weights are unrelated to mortality; that is, the baseline mortality is constant across birth weights (assuming a given gestational age).

There are 2 rare dichotomous confounding factors (X1 and X2). These factors increase the odds of mortality in a multiplicative fashion (odds ratio) and modify birth weight in an additive fashion (X1 reduces birth weight, and X2 increases birth weight).

We then add a simple dichotomous exposure (F) that decreases birth weight and increases mortality. We show that stratifying by F results in intersecting mortality curves, with babies exposed to F having lower mortality at low birth weights (thus demonstrating a simple underlying mechanism for intersecting mortality curves). We replicate a few empirical observations using this model. We fit all the models using a standardized normal distribution (mean = 0, standard deviation (SD) = 1), but we present all results using absolute birth weights.

Data sources

Our empirical examples are based on US linked birth and death certificates between 1995 and 2002, compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics (http://www.nber.org/data/lbid.html). We excluded nonresidents (0.1%); twins, triplets, and so on (3.0%); and missing birth weight (<0.1%). We further excluded births from California (13.5%), which lack data on smoking and clinical gestation.

Calculations

For births at term (37 weeks and higher), we used gestational age based on the date of the last menstrual period, and we estimated the parameters of the empirical “predominant” birth weight distributions within specified intervals of gestational age using the method proposed by Wilcox (http://eb.niehs.nih.gov/bwt/index.htm). Preterm births defined by the date of the last menstrual period yield heavily right-tailed birth weight distributions, presumably reflecting errors in gestational age. Defining preterm with the clinical estimates of gestation attenuates this problem. For the examples involving 33 and 35 weeks of gestation, we used the birth weight means and standard deviations proposed by Kramer et al. (17), obtained from a large population-based sample in which gestational age was generally assessed by early ultrasound. Their results are stratified by sex, and so we pooled the sex-specific estimates. We additionally excluded babies with a birth weight of >3,250 g at 33 weeks (4.9%) and of >4,250 g at 35 weeks (0.5%).

All birth weights were grouped into 250-g categories, and we fit only those points with at least 4 neonatal deaths (death from birth to 28 days) at the midpoint of the interval (thus introducing some imprecision). We do not have a formal algorithm to optimize the choice of model parameters in fitting the model to the empirical data, nor to assess the goodness of fit. As an alternative, we report how many model-predicted points fell outside the 95% confidence interval of the empirical rate. We calculated confidence intervals based on the approximation that, under a binomial distribution, a sample proportion follows a normal distribution when N is large.

RESULTS

Basic model

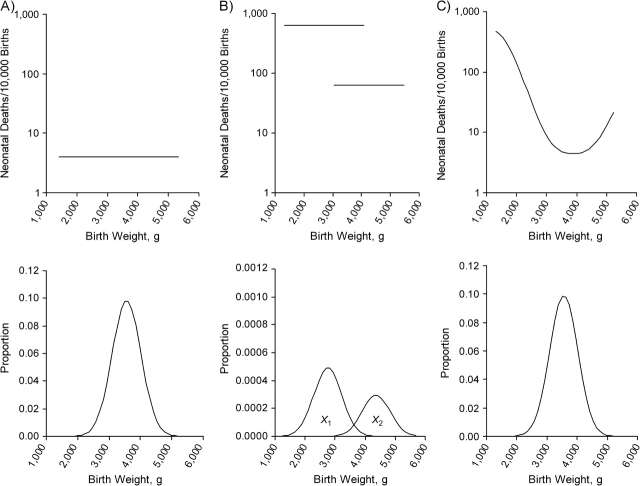

We assume a population of babies born at 40 weeks. The “target” birth weight has no impact on neonatal mortality, constant at 4 per 10,000 births (Figure 1A). We assume 2 rare factors, X1 and X2, which affect birth weight and mortality. We use the parameters reported in the paper by Basso et al. (1), after translating the relative risk into the odds ratio. We assume the mean target birth weight at 40 weeks to be 3,500 g, with a standard deviation of 460 g. X1 decreases birth weight by 782 g (SD = −1.7) and increases mortality to about 640 per 10,000 (i.e., with an odds ratio of 171). X2 increases birth weight by 782 g (SD = 1.7) and increases mortality to about 64 per 10,000 births (odds ratio = 16). These factors are extremely rare at term (0.5% for X1 and 0.3% for X2). The 2 populations are shown, with their respective mortality—still entirely independent of birth weight—in Figure 1B. (The figure does not show the unusual situation in which both X1 and X2 are present, although all calculations account for these babies.) When the weight-specific mortality curve is plotted across these categories, it produces the familiar pattern of a strong gradient between birth weight and mortality (Figure 1C), which is, however, purely the result of confounding. Mortality increases at progressively lower birth weights because an increasing proportion of babies have X1.

Figure 1.

Recapitulation of model's assumption. In A, a population has a mean birth weight of 3,500 g (standard deviation = 460) and mortality of 4 per 10,000 births. In B, 2 conditions, X1 and X2, affect 0.5% and 0.3%, respectively, of babies. Mortality is increased with odds ratios of 171 and 16, respectively, in babies with X1 and X2. (Note the different proportion scale in the y-axis of the birth weight distribution.) In C, the resulting mortality curve is shown.

Intersecting mortality curves

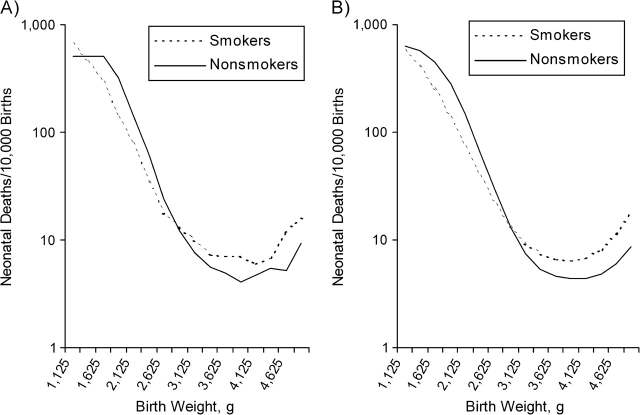

We now add an exposure (F), which decreases birth weight by 230 g (SD = 0.5) and increases mortality with an odds ratio of 1.5 (Figure 2A). Otherwise, there are no differences in the population exposed to F. (The frequency of F is unspecified, as all calculations are conditional on F, and the conclusions are independent of its frequency). X1 and X2 have the same parameters as before (Figure 2B). The weight-specific mortality curves for babies with and without F now intersect (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

A population of babies exposed to factor F (broken line) is added to the previous scenario. In A, the population with factor F has a mean birth weight of 3,270 g (standard deviation = 460) and mortality 1.5 times that of babies without F. In B, X1 and X2 affect 0.5% and 0.3%, respectively, of babies in each population. The birth weight of babies with F is shifted to the left in these populations, as in the main distribution. The effect of X1 and X2 on the mortality of babies with F is increased with odds ratios of 171 and 16, respectively. (Note the different proportion scale in the y-axis of the birth weight distribution.) In C, the intersecting mortality curves in babies with and without F are shown.

Under our simple assumptions, babies can be small because 1) their target birth weight is small, 2) F made them smaller, 3) X1 made them smaller, or 4) F and X1 together made them smaller. A small target weight (scenario 1) does not confer any additional risk. In contrast, scenarios 2, 3, and 4 are all associated with higher mortality but at quite different levels. The odds ratio with F alone (scenario 2) is 1.5, while the odds ratio with X1 is 171 or 256.5 (scenario 3 or 4). Conditional on F, 4 possible combinations of factors are defined by the presence or absence of X1 and X2 within each birth weight stratum.

Consider the mix of these combinations in 1 small stratum of birth weight (Figure 3). Among babies with an observed birth weight of between 2,200 and 2,299 g, those unexposed to F have a 10.6% chance of having X1, while babies at this same weight who are exposed to F have only a 4.8% chance of having X1. In the simple universe represented by our model, small babies with F have a lower probability of having X1 than do the small babies without F. Even though babies with F have higher mortality at all weights, the different proportions of X1 in those with and without F at this birth weight create the appearance of an advantage among small babies with F.

Figure 3.

Figure 2C is enlarged to show the proportions of X1 and X2 in babies with and without factor F (refer to the text) in the stratum 2,200–2,300 g (enclosed in the box). The solid curve represents the birth weight distribution of babies without factor F; the broken curve represents the distribution of babies with factor F. Data are from Table 1.

More generally, the intersection of mortality curves under our model results from the varying mix of factors that affect birth weight and mortality—a mix that is weighted differently at each birth weight. This phenomenon is illustrated in detail in Table 1, which shows the frequency of X1 and X2, given the birth weight and F in 3 birth weight strata (details about these calculations are provided in the Appendix). Within each example, all babies have the same observed birth weight. The first 2 columns of data show the target birth weight (in 100-g intervals) prior to the action of F, X1, and X2. The target birth weight is achieved by babies with none of the factors and by the tiny fraction of babies with both X1 and X2—for whom the 2 birth weight shifts cancel out but who nonetheless have extremely high mortality. The last column in Table 1 shows the death rate (per 10,000 births) for each category and the overall mortality, given F, in the specified birth weight stratum.

Table 1.

Frequencies of X1 and X2, Given Birth Weight and F, at 3 Birth Weightsa

| Factors | Target Birth Weight Intervalb | X1, X2 Frequency, Given Fc | Mortalityd per 10,000 Births | ||

| From | To | % in Babies With No F | % in Babies With F | ||

| Observed birth weight, 2,200–2,300 g | |||||

| No F | |||||

| No X1, no X2 | 2,200 | 2,300 | 89.3878 | 4.00 | |

| X1 only | 2,982 | 3,082 | 10.6102 | 640.45 | |

| X2 only | 1,418 | 1,518 | 0.0006 | 63.62 | |

| X1 and X2 | 2,200 | 2,300 | 0.0014 | 5,226.36 | |

| Overall | 71.60 | ||||

| F | |||||

| No X1, no X2 | 2,430 | 2,530 | 95.1535 | 6.00 | |

| X1 only | 3,212 | 3,312 | 4.8435 | 930.87 | |

| X2 only | 1,648 | 1,748 | 0.0016 | 95.12 | |

| X1 and X2 | 2,430 | 2,530 | 0.0014 | 6,215.36 | |

| Overall | 50.89 | ||||

| Observed birth weight, 2,900–3,000 g | |||||

| No F | |||||

| No X1, no X2 | 2,900 | 3,000 | 99.0950 | 4.00 | |

| X1 only | 3,682 | 3,782 | 0.8941 | 640.45 | |

| X2 only | 2,118 | 2,218 | 0.0093 | 63.62 | |

| X1 and X2 | 2,900 | 3,000 | 0.0015 | 5,226.36 | |

| Overall | 9.77 | ||||

| F | |||||

| No X1, no X2 | 3,130 | 3,230 | 99.5913 | 6.00 | |

| X1 only | 3,912 | 4,012 | 0.3854 | 930.87 | |

| X2 only | 2,348 | 2,448 | 0.0219 | 95.12 | |

| X1 and X2 | 3,130 | 3,230 | 0.0015 | 6,215.36 | |

| Overall | 9.68 | ||||

| Observed birth weight, 4,200–4,300 g | |||||

| No F | |||||

| No X1, no X2 | 4,200 | 4,300 | 98.8756 | 4.00 | |

| X1 only | 4,982 | 5,082 | 0.0074 | 640.45 | |

| X2 only | 3,418 | 3,518 | 1.1154 | 63.62 | |

| X1 and X2 | 4,200 | 4,300 | 0.0015 | 5,226.36 | |

| Overall | 4.79 | ||||

| F | |||||

| No X1, no X2 | 4,430 | 4,530 | 97.4323 | 6.00 | |

| X1 only | 5,212 | 5,312 | 0.0031 | 930.87 | |

| X2 only | 3,648 | 3,748 | 2.5631 | 95.12 | |

| X1 and X2 | 4,430 | 4,530 | 0.0015 | 6,215.36 | |

| Overall | 8.40 | ||||

Babies are assumed to have been born at 40 weeks' gestation and to have normally distributed target birth weight (mean = 3,500 g, standard deviation = 460).

The 2 columns, “From” and “To” under “Target Birth Weight Interval,” indicate the lower and upper limits of the birth weight that babies would have had in the absence of F, X1, or X2. All babies within each example have the same observed birth weight. Babies with none of the factors achieved their target birth weight (and have the lowest mortality), as well as babies with both X1 and X2, who, however, have elevated mortality.

These 2 columns report, for babies not exposed to F and babies exposed to F, respectively, the frequency of babies without either X1 or X2, with only 1 factor, or with both.

This column reports the mortality rates (per 10,000 births) for each of the 8 categories. The row labeled “Overall” indicates the mortality for the birth weight interval, stratified by F.

In this example, babies with F have lower mortality than do babies without F between about 1,500 and 2,950 g. At higher birth weights, the pattern reverses, and babies without F have lower mortality. The relative difference in mortality increases further at higher birth weights, because babies with F are much more likely to have X2 than those without F.

In the above scenario, we have assumed that X1 and X2 have the same effects on babies regardless of whether they are exposed to F. If this is the case, the use of relative birth weight (or z score-adjusted birth weight), as suggested by Wilcox and Russell (18), will remove the intersection of mortality curves by, in effect, removing the connection between F and birth weight. In terms of directed acyclic graphs (3), this means that birth weight is no longer a collider, and the weight-specific contrast in mortality can be displayed without the distortion that comes with adjustment for a collider.

Reality may be more complex if, for example, babies with X1 do not survive to term if they also have F, or in the presence of an interaction between F and X1 on birth weight or on mortality.

Empirical examples

We now show how this model behaves in reproducing empirical weight-specific mortality curves stratified by a given factor. The parameters used to fit the empirical examples are reported in Table 2. We present examples with smoking and selected categories of gestational age.

Table 2.

| Comparison | Selected Gestationa | Birth Weight Parameters | X1 Parameters | X2 Parameters | Points Outside 95% Confidence Interval (Total Points)b | |||||

| Mean (SD), g | Baseline Death Rate/10,000c | % | Shift SD (No. of g)d | Odds Ratio (Death Rate/10,000)e | % | Shift SD (No. of g) | Odds Ratio (Death Rate/10,000)f | |||

| Example 1 | ||||||||||

| Smokers | 39–41 weeks based on date of last menstrual period | 3,320 (453) | 5.64 | 0.54 | −1.37 (620) | 180 (922) | 0.30 | 1.70 (768) | 12.0 (67.8) | 1 (16) |

| Nonsmokersg | 39–41 weeks based on date of last menstrual period | 3,513 (452) | 4.00 | 0.54 | −1.80 (813) | 180 (665) | 0.30 | 1.70 (768) | 12.0 (47.3) | 3 (16) |

| Example 2 | ||||||||||

| 33 weeksh | Clinical estimate | 2,072 (392) | 41.00 | 2.20 | −1.30 (510) | 150 (3,818) | 3.80 | 1.00 (392) | 23.0 (865) | 2 (11) |

| 35 weeksi | Clinical estimate | 2,563 (427) | 29.00 | 1.30 | −1.42 (606) | 109 (2,407) | 0.60 | 1.00 (427) | 12.0 (337) | 0 (15) |

| 37 weeks | Based on date of last menstrual period | 3,138 (479) | 7.80 | 0.90 | −1.69 (809) | 185 (1,262) | 0.50 | 1.50 (718) | 10.0 (75.5) | 1 (18) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Except when noted, the means and standard deviations of the “predominant distribution” at each week were estimated by using Wilcox's method (5).

Number of fitted data points that fell outside the 95% confidence interval of the actual death rate for each 250-g category (total number of data points).

Baseline neonatal death rate (per 10,000 livebirths). This death rate applies at all birth weights absent the intervention of X1 and X2.

“Shift SD (no. of g)” indicates the amount of shift (in SD units) produced by X1 and X2. In parentheses, the corresponding amount in grams is reported.

Odds ratio for X1. In parentheses, the mortality rate for babies with only X1 is reported.

Odds ratio for X2. In parentheses, the mortality rate for babies with only X2 is reported.

In this example, we used a common SD of 452, given the negligible difference in the empirical ones. Smokers had a mean birth weight difference of −193 g (SD = −0.42).

The clinical estimate of gestation was used, after excluding birth weights of <500 g and >3,250 g. Pooled means and SDs were calculated from the pooled values of Kramer et al. (17).

The clinical estimate of gestation was used, after excluding birth weights of <500 g and >4,250 g. Pooled means and SDs were calculated from the pooled values of Kramer et al. (17).

Smoking.

Given that babies of smokers are lighter than babies of nonsmokers, it is possible that, at any given birth weight, they will have a higher gestational age. To minimize this potential problem, we derived the empirical parameters for smoking from US babies born between 39 and 41 weeks in 1995–2002. (Estimates for smokers would have been too unstable with a narrower interval). The calculated standard deviations of the predominant distributions were virtually identical (453 g and 452 g) for smokers and nonsmokers, while the mean birth weight was 193 g smaller for smokers. We used 452 g as the common standard deviation and assigned babies of smokers to have higher baseline mortality (with an odds ratio of 1.4 compared with nonsmokers). To obtain a reasonable fit, we allowed the effect of X1 on birth weight to be smaller in smokers than in nonsmokers (Table 2), since the shape of the mortality curve is strongly influenced by this parameter. Overall, we obtain a reasonable approximation of the empirical curves by assuming equal frequencies and equal mortality effects (in relative terms) for X1 and X2 in smokers and nonsmokers (Figure 4). (Fitted and empirical rates are reported in Appendix Table 2).

Figure 4.

Empirical (A) and calculated (B) weight-specific mortality curves are shown for smokers and nonsmokers, an example with births between 38 and 42 weeks of gestation, estimated by the date of the last menstrual period. Simulation parameters are shown in Table 2. Empirical data are based on National Center for Health Statistics data, US livebirths, 1995–2002.

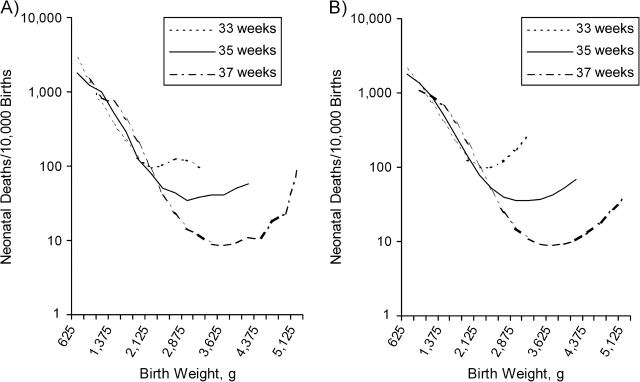

Selected categories of gestational age.

Intersecting weight-specific mortality curves also occur when different gestational ages are compared. In Figure 5A, the empirical mortality curves are shown for births at 33, 35, and 37 weeks. At some low birth weights, babies born at 33 weeks have lower mortality than do babies born at 35 or 37 weeks. This may occur through the mechanism illustrated above. To fit the curves, we allowed X1 and X2 to have a different prevalence at each gestational week, as well as different effects on birth weight and mortality (Table 2). We reproduced the general pattern of the mortality curves reasonably well (Figure 5B) by assigning higher proportions of X1 and X2 at earlier gestations. The fit is worst for the heaviest categories of weight at 33 weeks, most likely because of the contamination of the observed data by babies born at later gestations. Table 3 shows how, on the basis of the modeled curves, the different proportions of X1 and X2 at 1,500–1,599 g can lead babies born at 33 weeks to have lower mortality than their more mature counterparts do. (Calculations in the table are exact, unlike those in the figures, where mortality was estimated at the midpoint for each 250-g category).

Figure 5.

Empirical (A) and calculated (B) weight-specific mortality curves are shown for births at 33, 35, and 37 weeks of gestation; weeks 33 and 35 are based on clinical estimates of gestation, while week 37 is based on the date of the last menstrual period. Simulation parameters are shown in Table 2. Empirical data are based on National Center for Health Statistics data, US livebirths, 1995–2002.

Table 3.

Frequencies of X1 and X2, Given an Observed Birth Weight of 1,500–1,600 g at Gestational Ages 33, 35, and 37 Weeks, Based on Calculated Curvesa

| Gestational Age at Birth and Factors | Target Birth Weight Interval, gb | X1, X2 Frequency, %c | Mortality/10,000 Birthsd | |

| From | To | |||

| 33 weeks | ||||

| No X1, no X2 | 1,500 | 1,600 | 94.1656 | 41.00 |

| X1 only | 2,010 | 2,110 | 5.1137 | 3,817.74 |

| X2 only | 1,618 | 1,718 | 0.1190 | 9,342.25 |

| X1 and X2 | 1,108 | 1,208 | 0.6016 | 864.98 |

| Overall | 250.16 | |||

| 35 weeks | ||||

| No X1, no X2 | 1,500 | 1,600 | 87.8251 | 29.00 |

| X1 only | 2,076 | 2,176 | 12.1273 | 2,407.10 |

| X2 only | 1,649 | 1,749 | 0.0172 | 7,918.50 |

| X1 and X2 | 1,073 | 1,173 | 0.0304 | 337.24 |

| Overall | 318.85 | |||

| 37 weeks | ||||

| No X1, no X2 | 1,500 | 1,600 | 63.2200 | 7.60 |

| X1 only | 2,290 | 2,390 | 36.7739 | 1,233.51 |

| X2 only | 1,572 | 1,672 | 0.0053 | 5,845.57 |

| X1 and X2 | 782 | 881 | 0.0007 | 75.48 |

| Overall | 458.72 | |||

Refer to Table 2 for model parameters.

The 2 columns, “From” and “To” under “Target Birth Weight Interval,” indicate the lower and upper limits of the birth weight that babies would have had in the absence of X1 and X2. All babies in this table have the same observed birth weight of 1,500–1,600 g. Their target birth weight depends on the mean and standard deviation of the distribution for each week. X1 and X2 have different effects on birth weight and mortality at each week. (Refer to Table 2 for model parameters.)

Frequency of babies without either X1 or X2, with 1 factor, or with both.

Mortality rates (per 10,000 births) for each of the 4 categories. The row labeled “Overall” indicates the calculated mortality rate for babies in this birth weight interval. Parameters were sought to better fit the figures (using the midpoint of the 250-g interval), but calculations in the table accurately represent the actual interval. The modeled mortality rates per 10,000 births for the 1,500–1,749.9-g category (calculated at 1,625 g) were 210.4, 263.6, and 399.2 at 33, 35, and 37 weeks, respectively. The corresponding observed mortality rates were 220.4, 290.2, and 425.5.

DISCUSSION

Our model of birth weight-specific mortality yields curves very close to the empirically observed ones by making only a few simple—if radical—assumptions. The model assumes that birth weight is itself not causal and that the observed gradient of mortality with birth weight is due to unmeasured but exceedingly strong confounding factors with strong effects on birth weight and mortality. Although these assumptions may seem extreme, effects of this magnitude are, in fact, required to produce the empirical curves in the absence of a causal effect of birth weight (1). When assuming that birth weight has no causal effect, we can explain the optimum birth weight (the weight associated with the lowest mortality) as that at which the mix of confounders allows for the lowest mortality (1, 4).

There may be circumstances in which a baby's size directly causes mortality (e.g., macrosomia as a cause of birth injury or extreme thinness as a factor in neonatal starvation). Nonetheless, it is also apparent that reductions in birth weight can be irrelevant to mortality (as seen in babies born at high altitude) (5). In the case of smoking, the crossing of the mortality curves can be parsimoniously explained by assuming that birth weight has no direct or indirect effects on mortality. Because babies of smokers are smaller, they will be more mature than babies of nonsmokers at any given birth weight. We restricted our example to the interval of 39–41 weeks of gestation, which should ensure a relatively uniform level of developmental maturity in the 2 groups. Although this amounts to stratifying on a collider, we expect X1 and smoking to remain approximately independent among babies born at 39–41 weeks, because the association between smoking and preterm birth was modest in this data set (odds ratio = 1.25).

The empirical mortality curves at preterm weeks were reproduced fairly accurately, despite the limitations imposed by errors in gestational age, and the calculations showed how small babies at 33 weeks may have lower mortality than more mature babies with the same birth weight.

It is also interesting that, at preterm weeks, X2 appears to act independently of actual birth weight, with the upturn of the mortality curve happening at lower birth weights than among babies at term. The comparisons further suggest that both X1 and X2 are more prevalent at early gestational ages and may thus cause preterm birth, as well as growth restriction and mortality.

As previously discussed (1), the gradient of mortality with birth weight might be explained entirely by rare, potent, and as yet unidentified causes of death that independently affect birth weight. The entities “X1” and “X2” may not be single factors but combinations of very rare factors and, perhaps, very different combinations at different gestations. Some components of X1 (and X2) may already be clinically recognized but—because of their rarity—not acknowledged as an important source of the birth weight–mortality relation.

The model parameters for reproducing the empirical examples were chosen somewhat arbitrarily within the constraints of the model assumptions. We attempted to fit the curves with the same frequency of X1 and X2 for smoking to show that, in theory, these factors could be equally prevalent despite the differences in the weight-specific mortality. (We could have fit the model with a slightly weaker interaction by allowing babies of smokers to have a lower prevalence of X1 at 39–41 weeks). Even though we allowed for an interaction between X1 and smoking on birth weight, we did not need an interaction involving mortality, and the effect of birth weight was the same (i.e., none) in smokers and nonsmokers. These demonstrations are intended to provide a proof of principle rather than to argue that this model fully explains reality. Still, it is notable how well the model reproduces the empirical curves, especially given such simple assumptions and crude fitting procedure.

The phenomenon of intersecting curves is consistent with the presence of at least 1 unmeasured confounder that reduces birth weight and increases mortality. The presence of such confounding does not preclude the possibility that birth weight per se could be causally linked to mortality. If such confounders exist, however, the true biologic effect of birth weight on mortality would be weaker than what we observe.

The presence of unknown confounding factors as an explanation for intersecting mortality curves can also be applied to gestational age. Although fetal immaturity (birth at an early gestational age) is a plausible direct cause of death, some of the causes of preterm birth probably also contribute independently to mortality. In the presence of such confounding factors, the lower mortality of twins compared with singletons at early gestations can be explained with a mechanism analogous to that illustrated here, as previously suggested (19).

Our explanation for intersecting curves is parsimonious and biologically plausible. Any alternative explanation would seem to require complex interactions among the causal factors at play, birth weight, and mortality. If X1-like factors do not exist, then one would have to propose, for example, that the underlying effect of birth weight on mortality differs between smokers and nonsmokers. Additionally, there would have to be similar interactions between birth weight and mortality operating separately for each of the many factors that affect birth weight and produce intersecting curves.

When discussing intersecting gestational age-specific mortality curves, Klebanoff and Schoendorf (14) suggested that the underlying cause of preterm birth may influence the baby's chances of survival at a given gestational age. Here, we demonstrate this mechanism for birth weight. Under our model, the intersection of mortality curves is explained by the presence of confounding variables and the resulting unequal mix of those variables across the birth weight distribution. For those who would use birth weight as a general-purpose marker of risk, the inconvenient truth is that birth weight is likely affected by many unmeasured factors that carry very different risks of death. As a consequence, birth weight is—at best—an unreliable mediating variable or surrogate endpoint in the study of neonatal and infant mortality.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliation: Epidemiology Branch, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina (Olga Basso, Allen J. Wilcox).

This research was supported by the Intramural Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health (Z01 ES044003).

The authors thank Dr. Clarice R. Weinberg and Dr. David M. Umbach for their comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviation

- SD

standard deviation

APPENDIX

All babies in this example have an observed birth weight between 2,200 and 2,300 g. We calculated the target birth weight (the weight they would have had without X1, X2, and F) for each combination of X1, X2, and F. A baby with only X1 would have weighed 782 g more, that is, 2,982–3,082 g. A baby with F and X1 would have weighed 1,012 (782 + 230) g more, and so on. (Refer to “tBW [target birth weight] Interval” in Appendix Table 1).

The overall relative frequencies of each combination of X1 and X2 are determined by the parameters of the model. Because we condition on F, the sum of the 4 probabilities will be 1 within each category of F (“p(X1, X2|F)” in Appendix Table 1). For example, the probability of having neither X1 nor X2 is (1 − 0.005) × (1 − 0.003); that of having only X1 will be (0.005) × (1 − 0.003).

The probabilities of each of the 8 categories of target birth weight depend upon the normal distribution (“p(tBW|X1, X2, F)” in Appendix Table 1). Each of the target birth weight categories has different probabilities and contributes proportionally to the category of observed birth weight. We obtained these probabilities by taking the difference between the cumulative density functions at the ends of the interval, using the NORMDIST function in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington) software.

We multiplied p(X1, X2|F) by p(tBW|X1, X2, F). The resulting values represent the absolute probabilities of each combination of X1, X2, and target birth weight interval among babies with and without F, respectively. Dividing each row value by the sum of the 4 probabilities within the corresponding stratum of F, we obtain the X1, X2 composition in the 2,200–2,300-g weight stratum, as shown in the last column of the table.

Appendix Table 1.

| Factors | tBW Interval | p(X1, X2|F) | p(tBW|X1, X2, F) | p(tBW, X1, X2|F) | Interval Composition | |

| Between | And | |||||

| No F | ||||||

| No X1, no X2 | 2,200 | 2,300 | 0.99202 | 0.00219 | 0.0022 | 0.89388 |

| X1 only | 2,982 | 3,082 | 0.00499 | 0.05169 | 0.0003 | 0.10610 |

| X2 only | 1,418 | 1,518 | 0.00299 | 0.00001 | 0.0000 | 0.00001 |

| X1 and X2 | 2,200 | 2,300 | 0.00002 | 0.00219 | 0.0000 | 0.00001 |

| F | ||||||

| No X1, no X2 | 2,430 | 2,530 | 0.99202 | 0.00748 | 0.0074 | 0.95153 |

| X1 only | 3,212 | 3,312 | 0.00499 | 0.07575 | 0.0004 | 0.04844 |

| X2 only | 1,648 | 1,748 | 0.00299 | 0.00004 | 0.0000 | 0.00002 |

| X1 and X2 | 2,430 | 2,530 | 0.00002 | 0.00748 | 0.0000 | 0.00001 |

Abbreviation: tBW, target birth weight.

The example refers to babies with an observed birth weight between 2,200 and 2,300 g.

Appendix Table 2.

Calculateda and Empirical (95% Confidence Interval) Weight-specific Mortality Rates (per 10,000 Births) for Babies of Smokers and Nonsmokers Born at 38-42 Weeks (Estimated by Date of Last Menstrual Period)

| Weight, g | z Score | Calculated | Empirical | 95% Confidence Interval | Deaths, no. | No. |

| Smokers | ||||||

| 1,125 | −5.28 | 574.83 | 661.48 | 357.61, 965.35 | 17 | 257 |

| 1,375 | −4.73 | 403.85 | 450.98 | 270.87, 631.09 | 23 | 510 |

| 1,625 | −4.18 | 248.33 | 293.38 | 197.62, 389.14 | 35 | 1,193 |

| 1,875 | −3.62 | 138.03 | 136.05 | 98.60, 173.51 | 50 | 3,675 |

| 2,125 | −3.07 | 72.87 | 79.09 | 63.49, 94.69 | 98 | 12,391 |

| 2,375 | −2.52 | 38.46 | 34.37 | 28.81, 39.94 | 146 | 42,474 |

| 2,625 | −1.96 | 21.35b | 17.91 | 15.36, 20.46 | 189 | 105,554 |

| 2,875 | −1.41 | 13.11 | 13.07 | 11.63, 14.52 | 316 | 241,692 |

| 3,125 | −0.86 | 9.22 | 9.98 | 8.96, 11.00 | 367 | 367,901 |

| 3,375 | −0.31 | 7.42 | 7.23 | 6.38, 8.07 | 279 | 386,048 |

| 3,625 | 0.25 | 6.65 | 7.11 | 6.14, 8.08 | 206 | 289,814 |

| 3,875 | 0.80 | 6.48 | 7.06 | 5.78, 8.33 | 117 | 165,829 |

| 4,125 | 1.35 | 6.85 | 5.98 | 4.17, 7.79 | 42 | 70,255 |

| 4,375 | 1.91 | 8.13 | 6.79 | 3.89, 9.70 | 21 | 30,906 |

| 4,625 | 2.46 | 11.30 | 11.87 | 5.16, 18.58 | 12 | 10,113 |

| 4,875 | 3.01 | 18.08 | 15.86 | 1.97, 29.76 | 5 | 3,152 |

| Nonsmokers | ||||||

| 1,125 | −5.28 | 628.80 | 511.45 | 392.16, 630.75 | 67 | 1,310 |

| 1,375 | −4.73 | 566.83 | 509.28 | 410.03, 608.53 | 96 | 1,885 |

| 1,625 | −4.18 | 447.73 | 509.61 | 436.05, 583.17 | 175 | 3,434 |

| 1,875 | −3.62 | 286.18 | 316.35 | 280.52, 352.18 | 290 | 9,167 |

| 2,125 | −3.07 | 146.16 | 142.58 | 129.37, 155.80 | 441 | 30,929 |

| 2,375 | −2.52 | 64.72 | 61.61 | 57.07, 66.16 | 702 | 113,938 |

| 2,625 | −1.96 | 27.85b | 24.18 | 22.55, 25.82 | 840 | 347,357 |

| 2,875 | −1.41 | 13.07b | 12.19 | 11.52, 12.86 | 1,267 | 1,039,729 |

| 3,125 | −0.86 | 7.44 | 7.74 | 7.37, 8.12 | 1,623 | 2,095,936 |

| 3,375 | −0.31 | 5.34 | 5.53 | 5.26, 5.80 | 1,587 | 2,870,095 |

| 3,625 | 0.25 | 4.58b | 4.92 | 4.66, 5.19 | 1,348 | 2,738,139 |

| 3,875 | 0.80 | 4.36 | 4.11 | 3.83, 4.40 | 794 | 1,930,813 |

| 4,125 | 1.35 | 4.44 | 4.68 | 4.25, 5.10 | 459 | 981,709 |

| 4,375 | 1.91 | 4.86 | 5.46 | 4.80, 6.11 | 268 | 491,104 |

| 4,625 | 2.46 | 6.01 | 5.23 | 4.17, 6.29 | 94 | 179,774 |

| 4,875 | 3.01 | 8.71 | 9.20 | 6.75, 11.66 | 54 | 58,682 |

The calculated points were fitted at the midpoint of the 250-g birth weight interval, as reported in the table.

Data point falling outside the 95% confidence interval of the empirical rate.

References

- 1.Basso O, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR. Birth weight and mortality: causality or confounding? Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(4):303–311. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilcox AJ. Birth weight and perinatal mortality: the effect of maternal smoking. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(10):1098–1104. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez-Diaz S, Schisterman EF, Hernan MA. The birth weight “paradox” uncovered? Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1115–1120. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haig D. Meditations on birth weight: is it better to reduce the variance or increase the mean? Epidemiology. 2003;14(4):490–492. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000070402.42917.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcox AJ. On the importance—and the unimportance—of birthweight. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1233–1241. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalmers I. The search for indices. Lancet. 1979;2(8151):1063–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garner P, Kramer MS, Chalmers I. Might efforts to increase birthweight in undernourished women do more harm than good? Lancet. 1992;340(8826):1021–1023. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93022-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrimpton R. Preventing low birthweight and reduction of child mortality. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97(1):39–42. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yerushalmy J. Mother's cigarette smoking and survival of infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;88:505–518. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(64)90509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macmahon B, Alpert M, Salber EJ. Infant weight and parental smoking habits. Am J Epidemiol. 1965;82(3):247–261. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ananth CV, Platt RW. Reexamining the effects of gestational age, fetal growth, and maternal smoking on neonatal mortality [electronic article] BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph KS, Demissie K, Platt RW, et al. A parsimonious explanation for intersecting perinatal mortality curves: understanding the effects of race and of maternal smoking [electronic article] BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004;4(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platt RW, Joseph KS, Ananth CV, et al. A proportional hazards model with time-dependent covariates and time-varying effects for analysis of fetal and infant death. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(3):199–206. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klebanoff MA, Schoendorf KC. Invited commentary: what's so bad about curves crossing anyway? Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(3):211–212. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh203. discussion 215–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez-Diaz S, Wilcox AJ, Schisterman EF, et al. From causal diagrams to birth weight-specific curves of infant mortality. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(3):163–166. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcox AJ. Invited commentary: the perils of birth weight—a lesson from directed acyclic graphs. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(11):1121–1123. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj276. discussion 1124–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age [electronic article] Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E35. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilcox AJ, Russell IT. Birthweight and perinatal mortality. III. Towards a new method of analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1986;15(2):188–196. doi: 10.1093/ije/15.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lie RT. Invited commentary: intersecting perinatal mortality curves by gestational age—are appearances deceiving? Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(12):1117–1119. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.12.1117. discussion 1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]