Abstract

Dying cells often display a large-scale accumulation of autophagosomes and hence adopt a morphology called autophagic cell death. In many cases, it is agreed that this autophagic cell death is cell death with autophagy rather than cell death by autophagy. Here, we evaluate the accumulating body of literature that argues that cell death occurs by autophagy. We also list the caveats that must be considered when deciding whether or not autophagy is an important effector mechanism of cell death.

Cell death is associated with at least three morphologically distinct processes that have been named apoptosis, autophagic cell death (ACD) and necrosis (BOX 1). ACD is characterized by the large-scale sequestration of portions of the cytoplasm in autophagosomes, giving the cell a characteristic vacuolated appearance1. Autophagosomes can be identified by transmission electron microscopy as double-membraned vesicles that contain cytosol or morphologically intact cytoplasmic organelles (such as mitochondria or the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)). Autolysosomes, which arise from the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes, are defined by a single membrane that contains degenerating (and often unrecognizable) organelles that undergo degradation through the process of macroautophagy (called autophagy throughout this article)2.

Box 1 | Cell death modalities

The current nomenclature uses three terms to define morphologically distinct cell death modalities1,65.

Apoptosis

Also known as type 1 cell death, apoptosis is accompanied by a rounding up of the cell, retraction of pseudopods, reduction of cellular volume (pyknosis), chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation (karyorrhexis), few or no ultrastructural modifications of cytoplasmic organelles, and plasma membrane blebbing, but the integrity of the cell is maintained until the final stages of the process (see figure, part a). Hence, the term apoptosis should be applied exclusively to cell death events that occur while manifesting these morphological features66. The term programmed cell death (PCD) refers to death that occurs during development, and is not synonymous with apoptosis, as PCD can occur with non-apoptotic features. There are several distinct subtypes of apoptosis that, although morphologically similar, can be triggered through different biochemical routes (for example, through the intrinsic or the extrinsic pathway and with or without caspase activation). Furthermore, the apparent uniformity of apoptotic cell death might conceal heterogeneous functional aspects, such as whether or not dying apoptotic cells are recognized by the immune system1.

Autophagic cell death

Also known as type 2 cell death, autophagic cell death (ACD) is morphologically defined (especially by transmission electron microscopy) as a type of cell death that occurs in the absence of chromatin condensation but is accompanied by large-scale autophagic vacuolization of the cytoplasm (see figure, part b). Although the term ACD is a linguistic invitation to think that cell death is executed by autophagy, the term simply describes cell death with autophagy (FIG. 1).

Necrotic cell death or necrosis

Also known as type 3 cell death, necrotic cell death or necrosis is morphologically characterized by a gain in cell volume (oncosis), swelling of organelles and plasma membrane rupture and subsequent loss of intracellular contents (see figure, part c). Necrosis has traditionally been considered merely as an accidental, uncontrolled form of cell death that only occurs in pathological circumstances. However, evidence is accumulating that the execution of necrotic cell death might be finely regulated by a set of signal transduction pathways and catabolic mechanisms43,67. The term ‘necroptosis’ has been created to define regulated (rather than accidental) necrosis that involves signalling through the kinase RIP1 (REF. 68). Scale bars, 1 µm. Images reproduced, with permission, from Cell Death and Differentiation REF. 65 © (2007) Macmillan Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

Although there is no doubt that cells can manifest large-scale autophagy shortly before or during their death (referred to herein as cell death with autophagy), we share the opinion that autophagy is rarely, if ever, the mechanism by which cells actually die (referred to herein as cell death by autophagy) (FIG. 1). In this article, we will discuss whether the expression ACD, which is a linguistic invitation to think that cell death is executed by autophagy, is a misnomer.

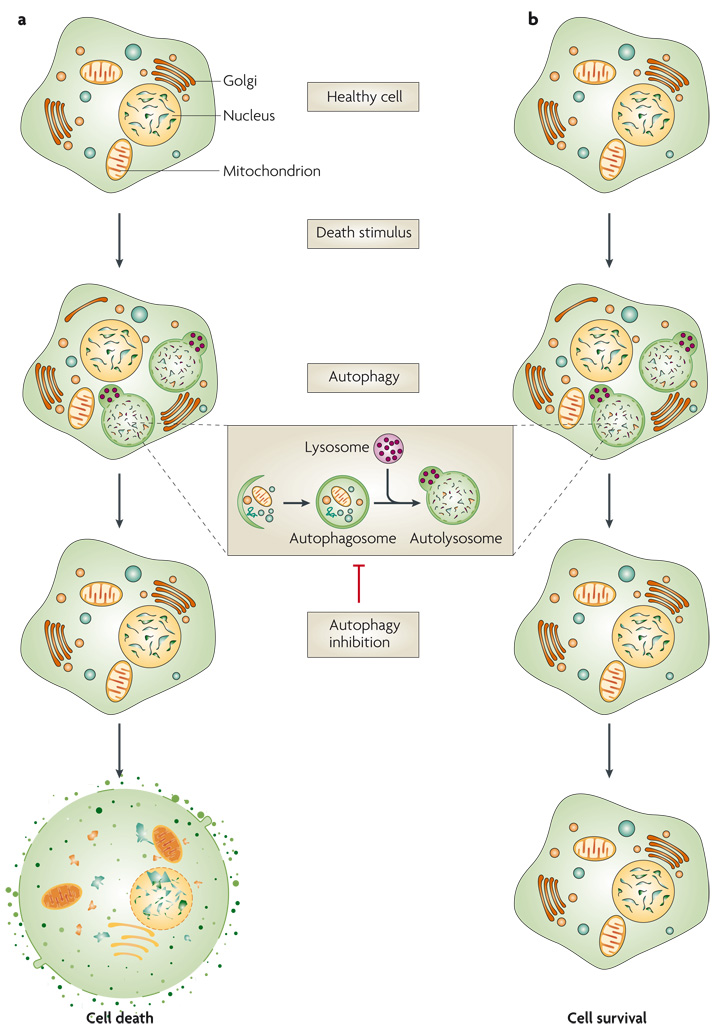

Figure 1. ‘cell death with autophagy’ versus ‘cell death by autophagy’.

In both scenarios, a death stimulus results in morphological features of autophagy, and in both cases, pharmacological or genetic inhibitors of autophagy block these morphological features. a | In cell death with autophagy, the inhibition of autophagy does not alter the fate of the cell (that is, cell death), although it might change the kinetics of this fate and the morphological appearance of the dying cell, as well as the read-outs of some assays used to measure cell death, the type of cell death pathway used by the cell and/or the rate of degradation of the cell. If inhibition of autophagy accelerates cell death, autophagy is considered to be a pro-survival pathway in the dying cell. b | If cell death were to occur by autophagy, the inhibition of autophagy would alter the fate of the cell and result in long-term cellular survival. Note that the blockade of autophagy only leads to the disappearance of autophagosomes if it intervenes at the level of autophagosome formation.

A brief history of ACD

Richard Lockshin coined the expression programmed cell death (PCD) more than 40 years ago, when he described the developmental cell death process in the intersegmental muscles of silk moths3. Remarkably, this first example of PCD had the morphology of ACD. However, apoptosis was regarded as the principal cell death mechanism following its initial description by Wyllie and Kerr4 and the discovery of the apoptotic machinery in Caenorhabditis elegans5 and caspases in mammals6 in the 1980s. After this eclipse by apoptosis, the notion of ACD regained momentum in the 1990s, prompted by the discovery of the autophagy-related (ATG) genes7 and the increasing realization that cell death can occur in a caspase-independent manner, with a non-apoptotic morphology8.

Some of the renewed momentum of ACD came from observations that, on further consideration, had explanations unrelated to ACD. For example, some researchers in the cell death field interpreted as ACD the autophagic vacuolization that is observed in degenerative muscle and neuronal diseases, such as Danon disease (vacuolar skeletal myopathy and cardiomyopathy) and Parkinson’s disease9,10. However, it is now well accepted that this increased autophagic vacuolization reflects defects in autophagosomal maturation and, hence, decreased, rather than increased, autophagy2 (TABLE 1). Further, Kuchino and co-workers reported that spontaneously regressing neuroblastomas died from non-apoptotic cell death while exhibiting “ultrastructural features of autophagic generation” that could be mimicked by transfecting activated Ras into cancer cell lines11. However, later studies showed that activated Ras triggers death in glioblastoma cells by hyperstimulation of macropinocytosis rather than by autophagy12 (TABLE 1). Moreover, several anticancer drugs, such as temozolomide13 and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid14, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, were reported to induce ACD in glioblastoma cells, although later discoveries indicated that autophagy induced by these agents exerts cytoprotective rather than cytotoxic effects15,16.

Table 1.

Difficulties in assessing the contribution of autophagy to cell death

| Category | Examples | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Misdiagnosed ‘autophagy’ | Ras-induced vacuolization of glioblastoma cells, which was initially interpreted as a sign of autophagy, actually results from large-scale macropinocytosis |

11,12 |

| Discrepancy in results of different assays used to measure cell death |

A partial inhibition of plasma membrane permeabilization by knockdown of ATG genes is not accompanied by an inhibition of DNA degradation |

35 |

| Increased numbers of autophagosomes might represent increased or decreased autophagy |

Accumulation of autophagosomes in the muscle from patients with Danon disease,in Lamp2−/− mice or after chloroquine intoxication; this accumulation is due to the failure to remove autophagosomes (through fusion with lysosomes) and hence reflects an inhibition of autophagy |

80,81 |

| Quantitative discrepancy between the magnitude of autophagy inhibition and cell death inhibition |

Complete inhibition of signs of autophagy (such as Lc3 lipidation and GFP–Lc3 aggregation in cytoplasmic dots) leads to only partial inhibition of cell death |

18,32,33 |

| Lack of specificity of autophagy inhibitors |

Pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy are nonspecific, whereas specific knockout or knockdown of ATG genes can affect autophagy-unrelated functions |

46,50,52 |

| Autophagy for optimal corpse clearance by phagocytes |

Failure to provide engulfment signals causes dying autophagy-deficient cells to persist in tissues, owing to inefficient clearance by phagocytic cells; lack of tissue regression can be misinterpreted as a block in cell death |

36 |

| Autophagy inhibition results in changes in morphology or rate of degradation of dead cells |

Genetic inactivation of ATG genes in Drosophila melanogaster results in the persistence of vacuolated salivary gland cell fragments with active caspase-3 and DNA fragmentation |

20 |

ATG, autophagy-related; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

In 2004, Lenardo and colleagues17 reported that, in U937 monocytoid cells and L929 fibro sarcoid cells, non-apoptotic cell death induced by caspase-8 inhibition is blocked by RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of two essential ATG genes, Becn1 (which encodes beclin-1 and is also called Atg6) or Atg7. During the same year, Tsujimoto and colleagues18 reported that, in response to etoposide or staurosporine, Bax−/−Bak−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) undergo non-apoptotic cell death accompanied by large-scale autophagic vacuolization, which can be reduced by knockdown of Atg5 or Becn1. Subsequently, many additional studies have been published that show a reduction or alteration in cell death following ATG knockdown in vitro8, and a few studies have reported similar findings in vivo19–21 (TABLE 2).

Table 2.

Removal of ATG genes for cell death avoidance in vivo

| Species | Cell type and death inducer |

Experimental removal of ATG genes that affects cell death |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Caenorhabditis elegans |

Neurons that degenerate as a result of uncontrolled ion fluxes through mutated channel proteins (MEC-4 and DEG-2) |

Mutation of atg-1 and RNAi of bec-1 (the orthologue of ATG6 (yeast) and BECN1 (mammals)), atg-8 (the orthologue of mammalian LC3) and atg-18 |

19 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | Transgenic expression of AtG1 in larval salivary glands |

RNAi of atg12 | 20 |

| Mus musculus | Neonatal hippocampal neurons dying after ligation of the carotid artery and transient hypoxia |

Neuron-specific knockout of Atg7 (Atg7flox/flox and nestin–cre) strongly reduces autophagy, caspase-3 activation, pyknosis, TUNEL-positivity and neuronal loss |

21 |

ATG, autophagy-related; DEG-2, degenerin-2; MEC-4, mechanosensory protein-4; RNAi, RNA interference.

In parallel with the growth in research on autophagy and cell death, there has been an explosion of research on autophagy and cell survival. The ability of autophagy to recycle nutrients, maintain cellular energy homeostasis and degrade toxic cytoplasmic constituents (and microbial intruders) helps to keep cells alive during nutrient and growth factor deprivation and other stressful conditions7. In cultured mammalian cells, ATG knockout or knockdown accelerates or enhances cell death that is induced by starvation, growth factor withdrawal, infectious agents and cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents8. Moreover, ATG genes have been shown to be essential for organismal survival during starvation in diverse eukaryotic organisms2,7.

Based mostly on the growing evidence that autophagy exerts cytoprotective effects, several investigators have proposed an operational definition of ACD that would clearly distinguish it from autophagy per se or from cell death with autophagy22–26. The under-lying principle of this operational definition is that ACD is not only accompanied by the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, but also involves an increase in autophagy that contributes to cell death. In other words, specific inhibition of autophagy should avoid irreversible loss of cellular functions and keep the cell alive.

Rescue from cell death: loopholes

The operational definition of ACD implies that suppression of autophagy reduces cell death. However, this definition fails to define what constitutes a biologically significant level of cell death suppression (in the setting of nearly complete inhibition of autophagy). It also fails to define whether abolition of autophagic features in dying cells without avoidance of cell death constitutes suppression of autophagic cell death, and whether the altered death kinetics in autophagy-inhibited dying cells signifies a role of autophagy as a lethal effector mechanism. We propose that these issues comprise quantitative and qualitative loopholes in the operational definition of ACD that allow most authors to ‘correctly’ use the term ACD, although, in many cases, the true role of autophagy in cell death remains uncertain.

Quantitative loopholes

In several studies, inhibition of autophagy results in partial inhibition of cell death27–34. In many cases, some early signs of cell death (such as plasma membrane permeabilization) are inhibited, whereas others (such as DNA degradation) are not35. This is commonly interpreted as evidence that there is both autophagy-dependent cell death (for example, as measured by assays that detect plasma membrane permeabilization) and autophagy-independent cell death (for example, as measured by the quantification of cells in which DNA has been degraded). An important alternative interpretation, that autophagy inhibition might selectively affect some of the ‘markers’ of cell death, is rarely considered. For example, one marker of apoptotic cell death is phosphatidylserine exposure on the plasma membrane and, at least in a mouse embryonic developmental model system, this process requires ATG-dependent ATP production in dying cells36. It is theoretically possible that autophagy inhibition could alter other more general markers of cell death, such as changes in plasma membrane permeabilization.

A related important concept is that autophagy inhibition might alter the kinetics of one marker compared with another marker of cell death, without altering the eventual percentage of cells that die. Unfortunately, most studies in the ACD literature fail to perform kinetic analyses of cell death at serial time points to confirm that cell death — not just one marker of cell death at one time point — is truly blocked, and few studies assess the effects of autophagy inhibition on clonogenic survival, which is often considered to be the gold standard for proving that an intervention has blocked cell death37. Results of kinetic studies often show delayed, rather than fully inhibited, cell death, and it is unclear how important the role of autophagy is in such cell death. Furthermore, results from clonogenic survival studies, although statistically significant, have been of unclear biological importance. For example, knockdown of Atg5 or Becn1 results in <10% clonogenic rescue in Bax−/−Bak−/− MEFs that have been treated with staurosporine or etoposide18, or in human lung cancer cells that are irradiated in the presence of a caspase inhibitor29. This type of partial inhibition of cell death poses a dilemma. On the one hand, one might argue that the experimental abolition of autophagy (down to baseline levels) should lead to complete avoidance of cell death if autophagy is responsible for cell death. On the other hand, one might argue, as is commonly done in the literature, that multiple cell death pathways operate concurrently, and that partial inhibition of cell death by autophagy inhibition reflects the coexistence of multiple death pathways. In this case, one would expect to see only a decrease in the total fraction of cell death that is truly autophagic following autophagy inhibition, except in scenarios in which autophagy is thought to lie upstream of apoptotic or necrotic cell death (see below).

How important is autophagy as a death effector mechanism if it is only responsible for an acceleration of cell death that would still occur in its absence, or for a fraction of the cell death that occurs in response to a certain stimulus in a given population of cells? In the case of apoptosis, there are many clear examples in which cell death is unequivocally blocked when components of the core apoptotic machinery are inactivated. For example, Bax−/−Bak−/− mice have multiple developmental abnormalities that result from absent PCD, including the persistence of interdigital webs, an imperforate vaginal canal and excess cells in the nervous system and haematopoietic system38. Furthermore, cells derived from Bax−/−Bak−/− mice are resistant to death that is induced by growth factor deprivation, B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2) homology-3 (BH3)-domain-only proteins, ultraviolet radiation, chemotherapeutic agents and ER stress39,40. To our knowledge, there is no similar evidence that autophagy-deficient cells show a complete resistance to cell death.

Qualitative loopholes

Beyond these quantitative loopholes in the operational definition of ACD, there are important qualitative loopholes that pose equally perplexing dilemmas. One of the clearest examples is with the model organism Dictyostelium discoideum, a soil amoeba that lacks Bcl2 and caspases, and hence is an ideal model for studying non-apoptotic death pathways41. In a D. discoideum monolayer system, starvation induces autophagy, whereas starvation together with differentiation-inducing factor (Dif) induces cell death that is characterized as autophagic or vacuolar cell death. This offers a unique opportunity to dissociate autophagy (which is Dif-independent) and cell death (which is Dif-dependent). In conditions of cell death induction (that is, starvation plus DIF), disruption of the autophagy gene atg1 blocks signs of autophagy and vacuolization, but cell death still occurs and has a necrotic morphology42. These observations are interpreted as evidence that ACD is a bona fide mechanism of cell death. Parallel to the consequences of apoptosis inhibition in animal cell death21,43, disruption of ACD results in necrotic cell death in D. discoideum. It is not clear how to distinguish between this interpretation — that is, ACD is a bona fide mechanism of cell death — and the alternative interpretation that ACD is not a death mechanism because autophagy inhibition does not block cell death.

Other technical considerations

A further limitation in assessing the role of autophagy in ACD arises from the use of pharmacological agents or genetic manipulations that are designed to suppress autophagy. Most studies of cell death by autophagy convincingly show efficient autophagy suppression. However, the specificity of agents that inhibit autophagy is an issue.

The pharmacological agent most commonly used to suppress autophagy is 3-methyladenine (3-MA), which interferes with the formation of autophagosomes by inhibiting the class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) vPS34. However, 3-MA is used at millimolar concentrations and might affect other targets, including class I PI3K (which inhibits autophagy), lethal stress kinases (such as p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-JUN N-terminal kinase) and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (which regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), one of the decisive events of both apoptosis and necrosis)44,45. A similar critique applies to lysosomotropic agents, such as chloroquine. Although such agents increase the lysosomal pH and inhibit the action of lysosomal hydrolases and the fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes, they have multiple nonspecific effects on cellular function46. Thus, the observation that 3-MA or chloroquine modulate cell death cannot be used as proof that autophagy is involved in the lethal process.

Genetic manipulations that affect ATG genes might also be problematic. Small interfering (si)RNA-mediated knockdown of one gene usually affects thousands of transcripts, meaning that multiple non-overlapping siRNAs should be used independently from each other and that experiments should ideally be controlled by retransfection of the cells with a cDNA that is not affected in its expression by the siRNA47. These types of controls have been missing in all of the reports on ACD that we have observed. In addition, the inhibition of autophagy causes an increase in the proteasome-mediated turnover of proteins48 and this might elicit the upregulation of cyto-protective antioxidant enzymes49. Finally, many, if not all, of the ATG gene products have functions outside of the autophagy pathway (BOX 2). In particular, this applies to beclin-1 (which might have a broad role in vesicular trafficking50 and interacts with apoptosis-regulatory proteins, such as BCL2 and BCL-xL(REF. 51)) and to ATG5 (which can translocate to mitochondria and induce MOMP after calpain-mediated cleavage52). Hence, depletion of beclin-1 might augment cellular survival by affecting cellular signalling processes through its role in vesicular trafficking, and depletion of ATG5 might affect MOMP, which is viewed as one of the decisive events that mark the point of no return in lethal signalling.

Box2 | Non-autophagic functions of ATG gene products

Several autophagy-related (ATG) proteins are known or are thought to have alternative, autophagy-independent functions. The Caenorhabditis elegans orthologue (UNC-51) and mammalian orthologue (ULK1) of ATG1 function in axonal elongation and branching69,70. ATG5 can be proteolytically activated to become a pro-apoptotic molecule that translocates to mitochondria and triggers mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization52, and the ATG5–ATG12 conjugate functions as a suppressor of innate immune signalling through interactions with the caspase recruitment domain of retinoic acid-inducible gene-1 (RIG1) and interferon-β promoter stimulator (IPS)71. Yeast Atg6, and perhaps its mammalian orthologue beclin-1, function in autophagy-independent vesicular trafficking pathways72. The BAX-interacting factor-1 (BIF1, also known as endophilin B1), which binds to beclin-1 through ultraviolet (UV) irradiation resistance-associated gene (UVRAG), is required for autophagy73 but was originally described as a pro-apoptotic factor74. UVRAG was originally discovered as a factor that affects UV sensitivity75 and is deficient in malformations of the left–right axis76. Beclin-1 has a B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2) homology-3 (BH3) domain77, which raises the theoretical possibility that it could function as a pro-apoptotic molecule. The knockout of AMBRA1 (activating molecule in beclin-1-regulated autophagy-1), another beclin-1 interactor, results in exencephaly78. Indeed, the knockout of ATG genes in mice results in rather distinct phenotypes that range from early embryonic to perinatal lethality or an increased incidence of tumours in adulthood2, which suggests that these genes have distinct functions outside of the autophagy-regulatory system. ATG16-like-1 (ATG16L1) might also have alternative functions, as a polymorphism in its non-conserved WD40 domain is associated with Crohn’s disease79, but is predicted not to affect its autophagy function.

Given the implication of ATG genes in cellular processes other than autophagy, it is an oversimplification to assume that the inhibition of cell death that results from the knockout or knockdown of one or a few ATG genes is due to suppression of the autophagic process. In this context, it is noteworthy that cytoprotective effects are mostly described for the knockout or knockdown of three genes — BECN1 (which encodes beclin-1 and functions in vesicle nucleation), ATG5 and ATG7 (which function in autophagosome elongation and completion). As noted above, at least two of these, ATG5 and BECN1, have been postulated to exert non-autophagic functions.

Death effector or corpse remover?

It was once postulated that high levels of autophagy might be considered as a ‘clean-up’ or ‘self-clearance’ mechanism in cells that are committed to die by apoptosis or necrosis53. This theory was originally developed to explain the clearance of apoptotic corpses in developmental settings, such as embryogenesis and insect metamorphosis, in which it was presumed that insufficient phagocytes were available for dead cell clearance. In such cases, dying cells would activate autophagy to target the contents of the cell for degradation by its lysosomes.

In 2007, the first evidence was published that indicated that autophagy is essential for the clearance of dying cells during developmental cell death, including in a mouse embryoid body cavitation model (which mimics the formation of the proamniotic cavity in early mammalian development)36 and in Drosophila melanogaster salivary gland regression20. In addition to the previously postulated cell-autonomous function of autophagy in the clearance of dead cells (which is the presumed mechanism in D. melanogaster salivary gland regression54), autophagy was found to have an unexpected function in signalling corpse removal by phagocytes.

Qu et al. 36 showed that autophagy-dependent ATP production is essential for the generation of engulfment signals in mouse embryoid bodies, including the ‘come-get-me’ signal (lysophosphatidylcholine secretion) and the ‘eat-me’ signal (phosphatidylserine exposure). Embryoid bodies derived from Atg5−/− or Becn1−/− embryonic stem cells displayed impaired phagocytic clearance of corpses that contain degraded (TUNEL-positive) DNA and impaired cavitation, and these defects were reversed by providing an external substrate for ATP generation. Moreover, lung and retinal tissues from Atg5−/− embryonic mice contained an increased number of apoptotic cells and showed ultrastructural evidence of impaired phagocytic removal of cell corpses. As the rate of cell death did not differ between wild-type and Atg5−/− or Becn1−/− embryoid bodies36, these results were interpreted to signify that the activation of autophagy in dying cells — at least in this developmental model system — is neither a pro-survival nor a pro-death mechanism; rather, it might be a means, in dying cells, of supplying energy for the emission of proper signals to ensure cell removal by neighbouring phagocytes.

Interestingly, Berry and Baehrecke reported similar findings with respect to the effects of autophagy inhibition on salivary gland degradation during D. melanogaster metamorphosis20. However, in this context, the role of autophagy in cellular degradation is thought to be cell autonomous54, and the authors interpreted these findings as “the first in vivo evidence that autophagy and atg genes are required for autophagic cell death”54. Transgenic expression of autophagy-inhibitory signalling molecules (such as DP110 (the active subunit of PI3K), AKT (also known as protein kinase B), activated RasV12 or the product of a dominant-negative, kinase-dead atg1 mutant) or removal of ATG genes (that is, loss-of-function mutation of either atg2, atg3, atg8 or atg18 or knockdown of either atg3, atg6, atg7 or atg12 by siRNA) caused the persistence of TUNEL-positive salivary gland cell fragments20. However, this persistence only gave rise to a delay of histolysis by ~24 hours. This delay could be prolonged by transgenic expression of the caspase inhibitor p35 (an inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein from baculovirus) or removal of either caspase activators (such as ARC, a D. melanogaster orthologue of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (APAF1) and CED4) or effector caspases (such as DRONC), indicating that both autophagy and apoptosis participate in the degradation of salivary gland cells20. However, it seems that salivary gland cells eventually disappear, even in conditions in which both autophagy and caspase activation are disabled, which suggests that both catabolic processes are dispensable for cell death to occur in this model. Furthermore, in a study by another group, the D. melano gaster APAF1 orthologue, DARK, was shown to be essential for salivary gland histolysis but dispensable for autophagy, which suggests that autophagy per se is not a ‘killing event’55.

These studies raise the question of whether autophagy inhibition-dependent blockade (or delay) of the degradation of salivary gland cell fragments (which display nuclear DNA fragmentation) meets the operational definition of ACD. The answer might depend more on how cell death, rather than how ACD, is defined. If one considers cell death as the failure to retain vital cellular functions, of which the best examples are perhaps clonogenic survival in dividing cells or persistent metabolic activity in terminally differentiated cells, these studies would suggest that autophagy is a crucial mechanism for the efficient clearance of dying cells, but not for death per se. However, if one defines cell death as the entire linear process that begins with the signal to irreversibly commit a cell to die and ends with the disappearance of the dead cell, these findings indeed constitute an important in vivo demonstration of an essential role for ATG genes in ACD.

Accomplice or sole perpetrator?

Another interesting question relating to the definitions of death and ACD is whether autophagy constitutes a death effector mechanism if it is genetically upstream of other death pathways, such as apoptosis or necrosis. In 2006, Espert et al.56 published the first genetic evidence that autophagy lies upstream of apoptosis: they showed that siRNA against two ATG genes, BECN1 and ATG7, completely suppressed apoptosis in CD4+ T lymphocytes that is triggered by C-X-C chemokine receptor-4 engagement by the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Subsequently, knockdown or knockout of ATG genes has been shown to block apoptotic death in other settings, including in photoreceptors that are exposed to oxidative stress57, in murine embryonic fibroblasts that are exposed to ER stress58 and in p53-overexpressing osteosarcoma cells59.

As the mechanisms that link ATG genes to apoptotic cell death are still poorly defined, it is unclear whether these observations indicate essential roles of the autophagy pathway in triggering apoptosis or, rather, alternative functions of components of the autophagy machinery in apoptosis signalling or execution. In either case, the above studies suggest that, in many settings, even if autophagy somehow participates in cell death, it is an accomplice in apoptotic cell death rather than a sole perpetrator in autophagic cell death.

Autophagy might also serve a similar accomplice role in necrotic cell death. In C. elegans, a gain-of-function mutation in the mechanosensor MEC-4 (the mec-4d mutant) that causes uncontrolled Ca2+ influx into neurons leads to neurodegeneration with features of excitoxin-induced necrosis. This cell death (as well as cell death induced by a gain-of-function mutation in the acetylcholine receptor channel subunit gene deg-3) is accompanied by increased autophagy and is inhibited for at least several days by mutations that affect the nematode orthologues of ATG1 or by RNAi of the orthologues of yeast ATG6, ATG8 or ATG18 (REF. 19). How autophagy might have such an accomplice role is an open question. Autophagy might disrupt the pro-death–anti-death equilibrium, for instance by the selective removal of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase60.

Does autophagic cell death exist?

Based on the considerations discussed above, the question arises whether there are physiological situations in which autophagy truly kills cells that would otherwise manifest long-term survival. There are some examples in which experimental induction of excessive autophagy can kill cells in model organisms in vivo or in mammalian cells in vitro. For example, in D. melanogaster larvae, transgenic expression of a highly active atg1 mutant induces large-scale autophagy and premature degradation of salivary glands, which, although accompanied by an increase in apoptosis61, is prevented by atg12 knockdown but not a p35 (apoptosis-inhibitory) transgene20. In cultured mammalian cells, BECN1 mutants that escape physiological regulation by BCL2 induce excessive levels of autophagy and cell death that can be inhibited by siRNA against ATG5 (REF. 51). In many other studies, cell death associated with excessive autophagy activation in response to cytotoxic agents or other stress stimuli has been shown to be blocked by 3-MA8.

Although experimentally induced excessive autophagy can cause cell death in non-mammalian organisms and in cultured mammalian cells, we are not aware of any model system that convincingly shows that physiological (or even pathological) cell loss in mammalian cells in vivo is executed by autophagy. one report shows that neuron-specific knockout of Atg7 can block neuronal cell loss that is induced by neonatal ischaemia or reperfusion damage of the brain21. However, in this system, neuronal cell loss occurs through an apoptotic pathway that can be interrupted by pharmacological inhibition of caspases and by a hypomorphic mutation of the gene that codes for apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF)21,62. The absence of Atg7 abolishes all signs of apoptosis that affect hippocampal pyramidal neurons of wild-type mice: proteolytic maturation of caspase-3 and caspase-7, oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation, TUNEL-positivity and pyknosis21. These results suggest that Atg7 is involved in a signal transduction pathway that facilitates activation of an apoptotic programme of cellular self-destruction, perhaps (but not necessarily) by autophagy. Alternatively, sublethal cellular stress induced by deficient autophagy (which in Atg7−/− neurons causes severe neurodegeneration in early adulthood)48 might elicit neuro-protective mechanisms that are similar to those triggered by ischaemic preconditioning63. Thus, whether autophagy is really involved in cellular demise remains elusive.

Conclusions and perspectives

As outlined above, the question of whether mammalian cell death can occur by autophagy cannot be answered definitively, although there are many examples of cell death with autophagy. In this sense, the term ACD should be considered to be a misnomer, and there are indeed overwhelming arguments (not discussed in this article) to suggest that autophagy has, above all, a role in protecting mammalian cells both in vitro and in vivo from nutrient stress, aggregates of misfolded proteins, organelle damage and microbes2,64. Importantly, at least some of the proteins that are essential for autophagy might also participate in signalling pathways that lead to autophagy-unrelated lethal processes (such as MOMP and caspase activation), and it will be important to distinguish between lethal signalling that depends on the expression of particular ATG gene products and true ACD in the future.

We propose two non-mutually exclusive approaches to tackle this problem: to develop specific genetic or pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy, or to inhibit autophagy by removing or depleting multiple ATG gene products and to provide solid evidence that autophagy inhibition (rather than off-target effects) has a major cytoprotective effect that leads to clonogenic survival or the permanent persistence of functional post-mitotic cells. Hence, investi gators working in the field should either redouble their efforts to provide unequivocal evidence for the existence of death by autophagy or avoid the term ACD if it only describes death with autophagy.

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene

Atg5 | Atg7 | Bak | Bax | Becn1

OMIM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM

Crohn’s disease | Danon disease | Parkinson’s disease

UniProtKB: http://www.uniprot.org

FURTHER INFORMATION

Guido Kroemer’s homepage: http://www.igr.fr/index.php?p_id=1072

Beth Levine’s homepage: http://www4.utsouthwestern.edu/idlabs/Levine/Levine_intro.htm

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by grants to B.L. from the National Institutes of Health, American Cancer Society and Ellison Medical Foundation, and to G.K. from Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Equipe labellisée), Agence Nationale de Recherche, Institut National du Cancer, Cancéropôle Île-de-France, the European Union (ApoSys, ChemoRes, DeathTrain, RIGHT) and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Contributor Information

Guido Kroemer, Institut Gustave Roussy, F-94805 Villejuif, France, Université Paris Sud, Paris 11, F-94805 Villejuif, France and INSERM, U848, F-94805 Villejuif, France.

Beth Levine, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Department of Internal Medicine and the Department of Microbiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, Texas 75390, USA.

References

- 1.Kroemer G, et al. Classifications of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2008 Oct 10; doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockshin RA, Zakeri Z. Programmed cell death and apoptosis: origins of the theory. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:545–550. doi: 10.1038/35080097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyllie AH, Kerr JF, Currie AR. Cell death: the significance of apoptosis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1980;68:251–306. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan J, Horvitz HR. A first insight into the molecular mechanisms of apoptosis. Cell. 2004;116:S53–S56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson DW, et al. Identification and inhibition of the ICE/CED-3 protease necessary for mammalian apoptosis. Nature. 1995;376:37–43. doi: 10.1038/376037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine B, Klionsky JD. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maiuri C, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka Y, et al. Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature. 2000;406:902–906. doi: 10.1038/35022595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anglade P, et al. Apoptosis and autophagy in nigral neurons of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Histol. Histopathol. 1997;12:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitanaka C, et al. Increased Ras expression and caspase-independent neuroblastoma cell death: possible mechanism of spontaneous neuroblastoma regression. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:358–368. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overmeyer JH, Kaul A, Johnson EE, Maltese WA. Active Ras triggers death in glioblastoma cells through hyperstimulation of macropinocytosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008;6:965–977. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanzawa T, et al. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:448–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao Y, Gao Z, Marks PA, Jiang X. Apoptotic and autophagic cell death induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:18030–18035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408345102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katayama M, Kawaguchi T, Berger MS, Pieper RO. DNA damaging agent-induced autophagy produces a cytoprotective adenosine triphosphate surge in malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:548–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carew JS, et al. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr–Abl-mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2007;110:313–322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L, et al. Regulation of an ATG7-beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science. 2004;304:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1096645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu S, et al. Role of Bcl-2 family proteins in a non-apoptotic programmed cell death dependent on autophagy genes. Nature Cell Biol. 2004;6:1221–1228. doi: 10.1038/ncb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samara C, Syntichaki P, Tavernarakis N. Autophagy is required for necrotic cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:105–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koike M, et al. Inhibition of autophagy prevents hippocampal pyramidal neuron death after hypoxic-ischemic injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;172:454–469. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306:990–995. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1509–1518. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: dual roles in life and death? Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:505–510. doi: 10.1038/nrm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Another way to die: autophagic programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1528–1534. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroemer G, Jaattela M. Lysosomes and autophagy in cell death control. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:886–897. doi: 10.1038/nrc1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akar U, et al. Silencing of Bcl-2 expression by small interfering RNA induces autophagic cell death in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2008;4:669–679. doi: 10.4161/auto.6083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turcotte S, et al. A molecule targeting VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma that induces autophagy. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim KW, Moretti L, Lu B. a novel selective inhibitor of caspase-3 enhances cell death and extends tumor growth delay in irradiated lung cancer models. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rashmi R, Pillai SG, Vijayalingam S, Ryerse J, Chinnadurai G. BH3-only protein BIK induces caspase-independent cell death with autophagic features in Bcl-2 null cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:1366–1375. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang M, et al. A small molecule inhibitor of isoprenylcysteine carboxymethyltransferase induces autophagic cell death in PC3 prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18678–18684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarlatti F, Maffei R, Beau I, Codogno P, Ghidoni R. Role of non-canonical Beclin 1-independent autophagy in cell death induced by resveratrol in human breast cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1318–1329. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reef S, et al. A short mitochondrial form of p19ARF induces autophagy and caspase-independent cell death. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu ZX, et al. A plant triterpenoid, avicin D, induces autophagy by activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1948–1957. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, McMillan-Ward E, Kong J, Israels SJ, Gibson SB. Oxidative stress induces autophagic cell death independent of apoptosis in transformed and cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:171–182. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qu X, et al. Autophagy gene-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development. Cell. 2007;128:931–946. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorburn A. Studying autophagy’s relationship to cell death. Autophagy. 2008;4:391–394. doi: 10.4161/auto.5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindsten T, et al. The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bak and Bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zong WX, Lindsten T, Ross AJ, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB. BH3-only proteins that bind pro-survival Bcl-2 family members fail to induce apoptosis in the absence of Bax and Bak. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1481–1486. doi: 10.1101/gad.897601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei MC, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tresse E, Kosta A, Luciani MF, Golstein P. From autophagic to necrotic cell death in Dictyostelium. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2007;17:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kosta A, et al. Autophagy gene disruption reveals a non-vacuolar cell death pathway in Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48404–48409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golstein P, Kroemer G. Cell death by necrosis: towards a molecular definition. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xue L, Borutaite V, Tolkovsky AM. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition and release of cytochrome c by anti-apoptotic nucleoside analogues. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:441–449. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scarlatti F, Granata R, Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Does autophagy have a license to kill mammalian cells? Cell Death Differ. 2008 July 4; doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatterjee T, Muhkopadhyay A, Khan KA, Giri AK. Comparative mutagenic and genotoxic effects of three antimalarial drugs, chloroquine, primaquine and amodiaquine. Mutagenesis. 1998;13:619–624. doi: 10.1093/mutage/13.6.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McManus MT, Sharp PA. Gene silencing in mammals by small interfering RNAs. Nature Rev. Genet. 2002;3:737–747. doi: 10.1038/nrg908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsumoto N, et al. Comprehensive proteomics analysis of autophagy-deficient mouse liver. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;368:643–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao Y, Klionsky DJ. Physiological functions of Atg6/Beclin 1: a unique autophagy-related protein. Cell Res. 2007;17:839–849. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pattingre S, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yousefi S, et al. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2006;8:1124–1132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. Autophagy functions in programmed cell death. Autophagy. 2008;4:359–360. doi: 10.4161/auto.5575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akdemir F, et al. Autophagy occurs upstream or parallel to the apoptososome during histolytic cell death. Development. 2006;133:1457–1465. doi: 10.1242/dev.02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Espert L, et al. Autophagy is involved in T cell death after binding of HIV-1 envelope proteins to CXCR4. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2161–2172. doi: 10.1172/JCI26185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunchithapautham K, Rohrer B. Apoptosis and autophagy in photoreceptors exposed to oxidative stress. Autophagy. 2007;3:433–441. doi: 10.4161/auto.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding WX, et al. Differential effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy on cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;282:4702–4710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Crighton D, et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu L, et al. Autophagic programmed cell death by selective catalase degradation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4952–4957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511288103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott RC, Juhasz G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu C, et al. Apoptosis-inducing factor is a major contributor to neuronal loss induced by neonatal cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:775–784. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gidday JM. Cerebral preconditioning and ischaemic tolerance. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:437–448. doi: 10.1038/nrn1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galluzzi L, et al. Cell death modalities: classification and pathophysiological implications. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1237–1243. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kroemer G, et al. Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12 Suppl. 2:1463–1467. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Necrosis, a well-orchestrated form of cell demise: signalling cascades, important mediators and concomitant immune response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:1371–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Degterev A, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nature Chem. Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogura K, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2389–2400. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou X, et al. Unc-51-like kinase 1/2-mediated endocytic processes regulate filopodia extension and branching of sensory neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5842–5847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jounai N, et al. The Atg5-Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14050–14055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kametaka S, Okano T, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. Apg14p and Apg6/Vps30p form a protein complex essential for autophagy in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22284–22291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takahasi Y, et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ncb1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takahashi Y, et al. Loss of Bif-1 suppresses Bax/Bak conformational change and mitochondrial apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:9369–9382. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9369-9382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perelman B, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel human gene encoding a 63-kDa protein and its sublocalization within the 11q13 locus. Genomics. 1997;41:397–405. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iida A, et al. Identification of a gene disrupted by inv(11)(q13.5;q25) in a patient with left-right axis malformation. Hum. Genet. 2000;106:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s004390051038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maiuri C, et al. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-XL and the BH3 domain of Beclin-1. EMBO J. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601689. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fimia GM, et al. Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature. 2007;447:1121–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature05925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Massey D, Parkes M. Genome-wide association scanning highlights two autophagy genes, ATG16L1 and IRGM, as being significantly associated with Crohn’s disease. Autophagy. 2007;3:649–651. doi: 10.4161/auto.5075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bolanos-Meade J, et al. Hydroxychloroquine causes severe vacuolar myopathy in a patient with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2005;78:306–309. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nishino I. Autophagic vacuolar myopathy. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2006;13:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]