Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Multi-Professional Triage Teams (MPTTs) were created to reduce the caseload of hospital orthopaedic clinics and this prospective study evaluated referrals made to a district general hospital orthopaedic department from a lower limb MPTT clinic.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Over 9 months, 277 referrals to a lower limb hospital orthopaedic clinic were assessed. The temporal delay to hospital clinic review between patients seen at the MPTT clinic and those referred directly by their general practitioner (GP) was analysed using an ANOVA test. A qualitative assessment of diagnoses given to patients reviewed at the MPTT clinic was performed.

RESULTS

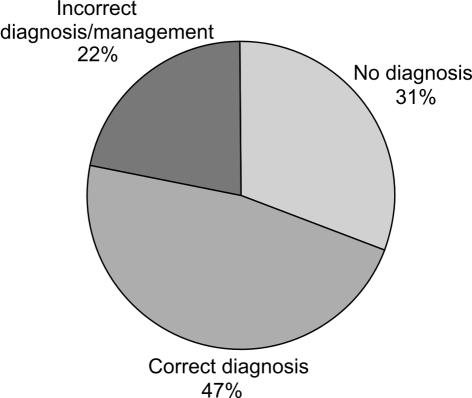

The 132 patients initially reviewed at the MPTT clinic and subsequently referred to a hospital consultant waited significantly longer (140 days compared to 62 days by direct GP referral; P < 0.05) to see an orthopaedic consultant. Over three-quarters of this patient cohort incorrectly identified the healthcare professional conducting their consultation at the MPTT clinic. One-third of cases (31%) had no diagnosis made and 22% were assessed as having an incorrect diagnosis.

CONCLUSIONS

Time delays, patient confusion regarding professional roles and diagnostic indecision are significant problems for patients referred to hospital orthopaedic clinics from MPTT clinics. This risks sub-optimal patient care and may lead to future medicolegal implications.

Keywords: General Practitioner with Special Interest (GPwSI), Referral, Outcome, Multi-Professional Triage Team (MPTT)

The NHS Plan formalised the concept of General Practitioners with Special Interests (GPwSI), proposing that by 2006 ‘at least 1 million more out-patient appointments will take place in the community rather than hospital’.1,2 This extended role was also introduced for other healthcare professionals including physiotherapists, nurses and podiatrists. Within the field of musculoskeletal medicine, the extended role for GPwSIs and physiotherapists were combined to create Multi-Professional Triage Teams (MPTTs). These clinics were developed within the primary care setting and aimed to reduce the quantity, but improve the quality, of referrals made to hospital-based orthopaedic care.

The development of GPwSI clinics, such as the MPTT clinic, has gained considerable momentum through policy rhetoric rather than a substantive evidence base for their introduction. To our knowledge, no published studies have assessed the temporal delays and perception of patients reviewed and subsequently referred by an MPTT clinic. This prospective study evaluated consecutive referrals made to a district general hospital orthopaedic department from a lower limb MPTT clinic over a 9-month period.

Patients and Methods

Patients initially consulting their GP were allowed to choose being referred to the MPTT clinic, staffed by GPwSIs and physiotherapists, or referral directly to a hospital clinic. Patients assessed at the MPTT clinic were either investigated and referred for physiotherapy or referred on to an orthopaedic consultant for a further opinion.

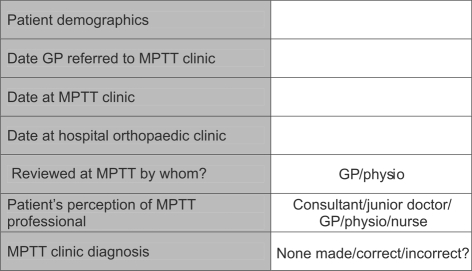

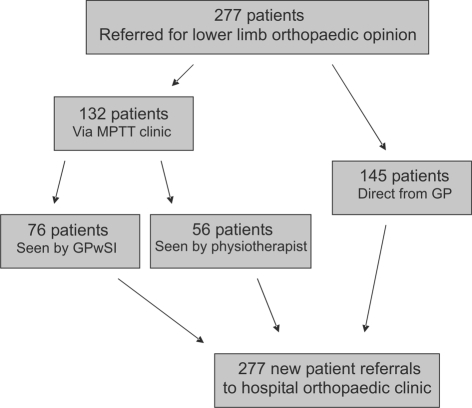

Over 9 months, a survey was performed of 277 consecutive patients referred to a lower limb orthopaedic clinic at a district general hospital. None of the patients referred to hospital clinics were triaged by either the senior author or other clinicians. A proforma (Fig. 1) was completed for 132 patients referred via the MPTT clinic and 145 patients referred directly from their GP (Fig. 2). For every patient initially reviewed at the MPTT clinic, it was recorded whether a diagnosis was made and if it was correct, as assessed by the senior author.

Figure 1.

Patient proforma for survey.

Figure 2.

Flow chart detailing the number of patients referred to a hospital orthopaedic clinic directly or via an MPTT clinic. Patients referred via an MPTT clinic were assessed by either a GP with a special interest (GPwSI) or a specialist physiotherapist.

Comparative statistical analysis of the temporal differences between the two groups was performed using an ANOVA (SPSS v.11.5; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)

Results

A total of 191 patients were seen in the MPTT clinic with 132 (69.1%) referred on to the hospital lower limb orthopaedic clinic. Over half of the patients referred on were assessed by a general practitioner with a special interest (76 out of 132), the remainder were reviewed by a specialist physiotherapist (Fig. 2). During the study period, a total of 277 new referrals were seen in the hospital clinic.

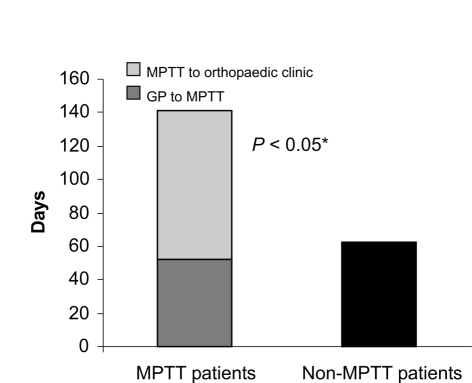

Figure 3 demonstrates the temporal delays for patients referred directly to a hospital orthopaedic clinic or patients initially assessed at an MPTT clinic. Patients were seen in the MPTT clinic a mean of 52.6 days (range, 19–135 days) following their GP referral and subsequently seen in the orthopaedic clinic 88.4 days (range, 18–255 days) later. This delay was significantly longer (P < 0.05) than the mean 62.4 days (range, 17–176 days) identified for patients referred directly by their GP to the hospital orthopaedic clinic.

Figure 3.

Referral time to hospital orthopaedic clinic. Comparison of delay from initial GP referral to hospital orthopaedic clinic review for patients seen either via an MPTT clinic or referred direct. *ANOVA statistical analysis.

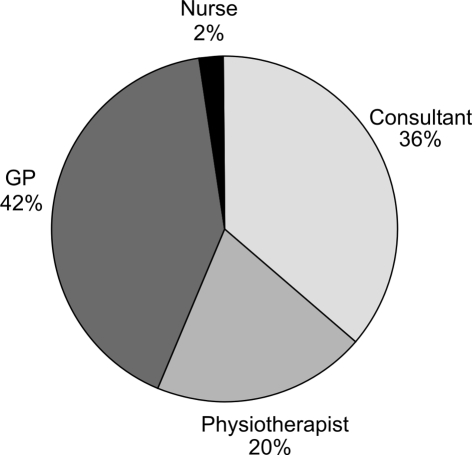

Figure 4 shows which healthcare professional each of the 132 patients assessed at the MPTT clinic thought they had seen. Over one-third of these patients reported they had previously seen an ‘orthopaedic consultant’ at the MPTT clinic when they had in fact been seen by a physiotherapist or GPwSI. Overall, 84% of this cohort of patients incorrectly identified the healthcare professional conducting their consultation at the MPTT clinic.

Figure 4.

Chart demonstrating which healthcare professional the patients attending an MPTT clinic believed they had seen.

Figure 5 shows the proportion of patients seen at the MPTT clinic that had the correct diagnosis, no diagnosis or the incorrect diagnosis made. The diagnosis made by the MPTT clinic agreed with that made by the orthopaedic consultant in 47% of cases. One-third of cases (31%) referred from the MPTT clinic had no diagnosis made and 22% were assessed as having an incorrect diagnosis.

Figure 5.

Assessment of diagnoses made for the cohort of patients initially assessed at the MPTT clinic.

Discussion

The introduction of GPwSIs and clinics such as the MPTT clinic was born out of the laudable goal of improving patient services as well as a broader shift in care toward the primary care sector.2,3 Few studies have considered the effects of this significant change, the majority being produced from researchers in a primary care setting analysing short-term general health measures.4 Baker et al.5 showed that short-term health outcomes, quantified using the SF-36 health survey, are similar for patients assessed at a GPwSI clinic as those referred directly to hospital clinics. That study, conducted entirely from a primary care perspective, made no assessment of the temporal delays involved or the diagnoses made.

In this study, patients seen by the MPTT clinic and subsequently referred to hospital had to wait significantly longer to see an orthopaedic consultant (140 days versus 62 days; P < 0.05) than those patients referred directly to a hospital clinic by their GP.

The diagnostic accuracy of the lower limb MPTT clinic assessed in this study (Fig. 5) is subjective and, therefore, potentially open to bias. With 22% of cases referred from the MPTT clinic deemed to have an incorrect diagnosis and one-third with no diagnosis, this may represent the case-load complexity inherent in lower limb musculoskeletal medicine or evidence of the learning curve of the MPTT clinicians. However, many patients seen in the MPTT clinic had the same diagnosis made by both the initial referring GP and the hospital consultant, suggesting the GPwSI clinic was a superfluous tier of care for this patient cohort.

It is unlikely that these results would be replicated within the setting of an upper limb MPTT clinic. Several common upper limb conditions (e.g. carpel tunnel syndrome and tennis elbow) are amenable to rapid diagnosis and initial treatment in a GPwSI-led clinic, prior to referral to a hospital consultant.

Furthermore, in this study, patients reviewed and referred via a MPTT clinic were generally unsure of the healthcare professional that had previously assessed them (Fig. 4). The resulting uncertainty can lead to mixed messages, heightened patient concerns and unrealistic expectations.

The delay to secondary care, the patient confusion regarding professional roles and the diagnostic indecision may not only have a detrimental effect on the standard of patient care, but may well have future medicolegal implications. Further, the benefits of the recent reduction in waiting list times to less than 6 months is not achieved for patients referred to the MPTT clinic and who subsequently require surgery due to the inherent delay.

Examples of avoidable delays include long-standing degenerative changes in the knee being over investigated when joint replacement was more appropriate and a symptomatic and undiagnosed lateral discoid meniscus.

There is variation in the organisation of GPwSI-led clinics, some running concurrently with consultant clinics affording the opportunity for a more consensual professional opinion and mutual education. Pearce et al.6 showed that, although an extended role for physiotherapists is generally acceptable to patients, 81% of cases required consultant input and 76% of dissatisfied patients had not seen a consultant. Currently, no competency framework exists for GPs with a special interest in musculoskeletal medicine and no on-going appraisal of patient outcomes.7

Conclusions

No comprehensive evidential support exists detailing the clinical outcome of patients seen at GPwSI-led clinics, such as a MPTT clinic. This study highlights concerns regarding patients referred on for a consultant opinion; however, the outcome of patients seen in these clinics and not referred to an orthopaedic consultant is unknown. In view of the data presented, this may be of concern and should necessitate further evaluation and audit.

References

- 1.Department of Health. The NHS Plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: The Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Improvement, expansion and reform – the next 3 years: priorities and planning framework 2003–2006. London: The Stationery Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Royal College of General Practitioners. Implementing a scheme for General Practitioners with Special Interests. London: The Stationery Office; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kernick D, Mannion R. Developing an evidence base for intermediate care delivered by GPs with a special interest. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:908–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker R, Sanderson-Mann J, Longworth S, Cox R, Gillies C. Randomised controlled trial to compare GP-run orthopaedic clinics based in hospital outpatient departments and general practices. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:912–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearse EO, Maclean A, Ricketts DM. The extended scope physiotherapists in orthopaedic out-patients – an audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:653–5. doi: 10.1308/003588406X149183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay EM, Campbell A, Linney S, Wise E. Development of a competency framework for general practitioners with a special interest in musculoskeletal/rheumatology practice. Rheumatology. 2007;46:360–2. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]