Abstract

Background:

HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome is strongly associated with antiretroviral treatment in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Niacin is thought to affect hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) expression in peripheral and intra-abdominal fat (IAF).

Objective:

This study investigated the effect of extended-release niacin (ERN) on adipose HSL and LPL expression in patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome.

Methods:

Changes in IAF and peripheral fat content and HSL and LPL expression were examined in 4 HIV-infected patients recruited from a prospective study treated with ERN. Patients underwent limited 8 slice computerized tomography abdominal scans, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans, and skin punch biopsies of the mid-thigh at baseline and after 12 weeks of ERN. All subjects were on stable highly active antiretroviral therapy prior to and during the study. Changes in body habitus were self-reported.

Results:

Normalized HSL expression decreased in 3 patients and normalized LPL expression increased in all 4 patients when comparing pre- and post-ERN treated samples. All subjects showed a decrease in total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) levels.

Conclusions:

Preliminary analysis suggests ERN may induce changes in HSL and LPL expression. This method is a feasible approach to identify changes in adipose RNA expression involved with lipolysis.

Keywords: extended-release niacin, HIV, lipodystrophy syndrome, hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), lipoprotein lipase (LPL)

Introduction

The significant reduction in morbidity and mortality associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection seen with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy has been accompanied by an increase in adverse effects. One of the most common complications is HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome, which is observed in 30%–60% of patients treated with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and/or protease inhibitors (Bodasing and Fox 2003). This syndrome is characterized by changes in body fat distribution including an increase in centralized fat in the abdomen and cervicodorsal region and a decrease in fat in the face, buttocks, and upper and lower limbs (Carr 2003). Although it is not clear whether peripheral lipoatrophy poses any health risk, central fat accumulation has been associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients (Behrens et al 2003). These changes in body shape are psychologically disturbing to patients, as they are often perceived as visible indicators of their HIV status (Fernandes et al 2007). There is presently no standard therapy to treat HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome (Schambelan et al 2002).

Fessel et al (2002) reported more than a 25% reduction of intra-abdominal fat (IAF) in patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy treated with ERN. Niacin has long been used in the treatment of dyslipidemias, especially hypertriglyceridemia, and has been considered as a treatment for HIV-associated lipodystrophy. Niacin is thought to inhibit hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and enhance lipoprotein lipase (LPL) expression in peripheral fat. Conversely, it inhibits LPL and enhances HSL expression in intra-abdominal fat (IAF) (Farmer and Gotto 1996). HSL is associated with fat mobilization, especially in peripheral adipose tissue, while LPL has been linked to visceral fat storage (Reynisdottir et al 1997). The objective of this study was to identify changes in RNA expression of HSL and LPL in relation to clinical and laboratory results and imaging measurements. Of interest is the RNA expression of HSL and LPL in subcutaneous fat in HIV-infected patients reporting lipodystrophy treated with ERN.

Methods

Patients were recruited from a prospective pilot study examining the safety and tolerability of ERN on HIV-infected individuals with hypertriglyceridemia (Souza et al 2002). Patients were eligible if they had self-reported body habitus changes confirmed by their physician. Patients had to have received stable potent antiretroviral therapy for at least 12 weeks prior to study entry and during the study. The only exclusion criterion was pregnancy. Informed consent was obtained from all participating patients as per guidelines approved by the Committee on Human Studies of the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Eligible patients were started on ERN at 500 mg once daily at bedtime. The dose of ERN was increased by 500 mg every 4 weeks to a maximum dose of 1500 mg once daily, which was continued for the remainder of the study. Patients underwent limited 8 slice computerized tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen to estimate the amount of IAF content (Smith et al 2001), dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans to determine peripheral fat content, and skin punch biopsies of the mid-thigh to determine RNA expression of HSL and LPL at baseline and after 12 weeks of ERN therapy. The study was completed after 24 weeks of ERN therapy.

A 3-mm skin punch biopsy was performed on the upper lateral thigh at entry and 12 weeks after the initiation of ERN treatment. Follow-up biopsies at the end of the study were obtained adjacent to the initial baseline biopsy. Subcutaneous fat tissue was removed from the rest of the biopsy specimen using a scalpel and forceps and stored in tissue-freezing medium and RNA-Later for nucleic acid extraction at −80 °C. RNA was extracted from the fat tissue using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit for RNA extraction (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of the RNA was assessed using UV spectrophotometry and reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) of the cDNA with β-globin primers.

cDNA was synthesized from the total cellular RNA using the GeneAmp Gold RNA PCR Reagent Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR with β-globin primers (5’-GAA GAG CCA AGG ACA GGT AC-3’ and 5’-CAA CTT CAT CCA CGT TCA CC-3’) was performed using the following reaction mix: nuclease free water, 10 × Taq buffer with MgCl2, 1.25 dNTP, 10% DMSO, 5’ and 3’ β-globin primers, and Taq polymerase. 2.0 μL of cDNA was added to the reaction mixture. 1.0 μL of peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNA was used as a positive control and the negative control consisted of the reaction mixture with no added DNA. The reaction conditions were: an initial extension of 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 3 min in a PE9700 Thermalcycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT, USA). 10.0 μL of each reaction was resolved on a 1.5% agarose/1.0% NuSieve gel.

PCR amplification of the cDNA was performed using HSL primers (5’-CCC ATC ATC TCC ATC GAC TA-3’ and 5’-CTT AAC TCC A-3’) and LPL primers (5’-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA ATA GGG-3’ and 5’-GTG CCA TAC A-3’) (Montague et al 1998). The reaction mix contained: nuclease free water, 10 × Taq buffer with MgCl2, 1.25 dNTP, 10% DMSO, 5’ and 3’ HSL and LPL primers, and Taq polymerase. The cycling conditions were the same as mentioned above, with the exception of an adjusted annealing temperature of 57 °C for the HSL primers and 52 °C for the LPL primers. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5%/1.0% agarose/NuSieve gel. For the control amplified product (β-globin) and HSL/LPL products, the gels were scanned by a densitometer. The ratio of the measured gene (HSL or LPL) to the β-globin was calculated from the pre- and post-ERN subcutaneous fat tissues to determine the relative changes in HSL and LPL expression.

Results

Four out of 10 patients enrolled in the prospective pilot study reported lipodystrophy and were eligible for this study. The baseline characteristics of the subjects are displayed in Table 1. None of the patients had significant adverse effects and all were able to tolerate 1500 mg of ERN (Souza et al 2002). Viral load prior to initiating therapy was undetectable in 3 patients and 205 copies/mL in the 4th patient. CD4+ count ranged from 413 to 619 cells/mm3 with a mean of 502 cells/mm3.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HIV-infected individuals with lipodystrophy treated with extended-release niacin

| Patient | Age (yrs) | Gender | Weight (kg) | Triglyceride (mg/dL) | IAF content (kg) | Bilateral leg fat (kg) | CD4 count (cells/mm3) | Viral load (copies/mm3) | Current ART regimen | HDL (mg/dL) | Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | M | 93.2 | 1146 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 426 | 205 | lamivudine, lopinavir/ritonavir, stavudine | 34 | 311 |

| 2 | 58 | M | 98.6 | 300 | 8.2 | 10.3 | 413 | <50 | zidovudine/ lamivudine, nelfinavir mesylate | 37 | 220 |

| 3 | 43 | M | 85.5 | 1264 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 619 | <50 | efavirenz, lopinavir/ritonavir | 28 | 317 |

| 4 | 47 | M | 64.0 | 1189 | NA | NA | 550 | <50 | indinavir sulfate, lamivudine, stavudine | 26 | 248 |

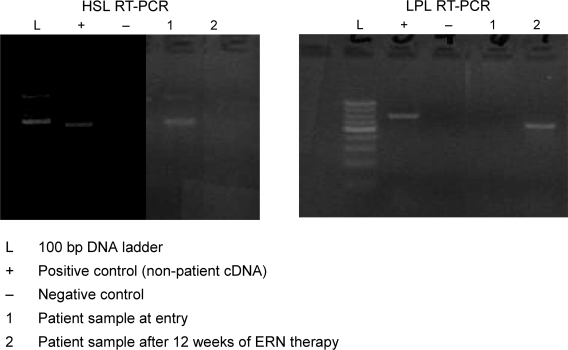

After 12 weeks of ERN therapy, skin biopsies for HSL and LPL were performed. No complications from the skin biopsies were encountered. RT-PCR analysis showed all 8 samples were positive for β-globin. Densitometry readings of the RT-PCR products resulted in pixel densities (light units) for each value (β-globin, HSL, LPL RNA expression). HSL and LPL RNA expression values were then divided by the respective β-globin RNA expressions, which normalized each valued as a ratio. This approach permitted comparisons between individual samples for each patient where each patient was his/her own control. Three of the 4 specimens showed a decrease in normalized HSL expression when comparing pre- and post-ERN treated samples through RT-PCR analysis. An increase in normalized LPL expression was observed in all 4 specimens. Representative samples of HSL and LPL assays are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

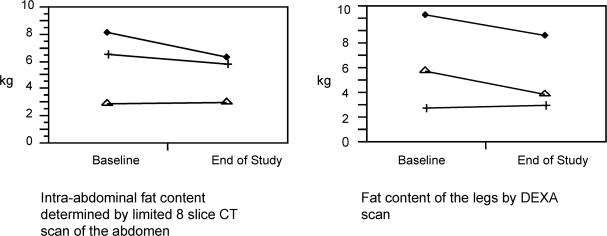

Changes in intra-abdominal fat and peripheral fat content of HIV-infected individuals with lipodystrophy treated with extended-release niacin.

After 24 weeks of ERN therapy, all patients showed a decrease in TC and TG levels as seen in Table 2. The mean change in TG level was −385 mg/dL. The mean change in TC level was −34 mg/dL. Three of the 4 patients completed CT and DEXA scans. The changes in IAF of each patient determined by the limited 8 slice abdominal CT scans are shown in Figure 2. The mean percent change in IAF at the end of the study from baseline was −9.8%. The changes in fat content of both legs of each patient determined by DEXA are also shown in Figure 2. The mean percent change in leg fat from baseline was −14.0%.

Table 2.

Changes in weight (kg), triglyceride, IAF, bilateral leg fat, and normalized HSL and LPL expression in HIV-infected individuals treated with extended-release niacin

| Patient | Δ in weight (kg) | Δ in triglyceride (mg/dL) | Δ in total cholesterol (mg/dL) | % Δ in IAF | % Δ in bilateral leg fat | Δ in HSL | Δ in LPL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.46 | –407 | –69 | –10.4 | 8.4 | –0.06 | 0.26 |

| 2 | –8.18 | –118 | –25 | –22.7 | –16.3 | –0.14 | 0.23 |

| 3 | 1.37 | –940 | –21 | 3.7 | –34.2 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

| 4 | –1.36 | –76 | –20 | NA | NA | –0.38 | 0.82 |

Figure 2.

Ethidium bromide stained gel of RT-PCR amplified samples using HSL (left) and LPL (right) primers.

Discussion

By controlling hypertriglyceridemia and moderating HSL and LPL expression, ERN may potentially decrease IAF and increase peripheral fat content. Although the changes in enzyme expression were not quantitated, semi quantitative analysis shows that LPL expression increased after treatment with ERN in all 4 patients, and HSL expression decreased in 3 patients. Only 2 patients demonstrated a loss of IAF and only 1 patient showed an increase in bilateral leg fat. There was no relationship between the change in weight of the patients and the change in either visceral or peripheral adipose tissue content.

A larger sample size and a control group may have produced a clearer effect. In addition, the skin punch biopsies were performed after only 12 weeks of ERN treatment. It is possible that 12 weeks were not sufficient for ERN to exert its full effect on enzyme expression, and therefore on lipolytic activity. This group had a selection bias, as patients self-reported body changes to be eligible to participate in this study, and as a result, may have impacted the results. Some of these individuals may have had mild body habitus changes and the changes from ERN treatment may have been too small to discern. The patients were used as their own controls, which does not allow for examination of the natural progression of lipodystrophy, and compliance was not measured. Furthermore, weight loss due to diet and exercise likely had a considerable impact on adipose changes, which were not controlled for nor quantified in this study.

The results of this pilot study show this method can be used to determine changes in adipose RNA expression of HSL and LPL in HIV-infected individuals treated with ERN. A larger definitive study is needed in the future to validate the use of ERN in HIV-infected individuals suffering from HIV-associated lipodystrophy.

Acknowledgments

This investigation/manuscript was supported by Research Centers in Minority Institutions award P20 RR11091 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Defense (DOD) Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC) award W81XWH-07-2-0073. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCRR/NIH and DOD.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Behrens GMN, Meyer-Olsen D, Stoll M, et al. Clinical impact of HIV-related lipodystrophy and metabolic abnormalities on cardiovascular disease. AIDS. 2003;17:S149–54. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodasing N, Fox R. HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome: description and pathogenesis. J Infect. 2003;46:149–54. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. HIV lipodystrophy: risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. AIDS. 2003;17:S141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer JA, Gotto AM. Choosing the right lipid-regulating agent: a guide to selection. Drugs. 1996;52:649–61. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes APM, Sanches RS, Mill J, et al. Lipodystrophy syndrome associated with antiretroviral therapy in HIV patients: considerations for psychosocial aspects. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem. 2007;15:1041–5. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692007000500024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel WJ, Follansbee SE, Rego J. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol is low in HIV-infected patients with lipodystrophic fat expansions: implications for pathogenesis of fat redistribution. AIDS. 2002;16:1785–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber MT, Mondy KE, Yarasheski KE, et al. Niacin in HIV-infected individuals with hyperlipidemia receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:419–25. doi: 10.1086/422144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton JR, Blazing MA, Hagar J, et al. Extended-release niacin vs gemfibrozil for the treatment of low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1177–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leow MKS, Addy CL, Mantzoros CS. Human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy-associated metabolic syndrome: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1961–76. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague CT, Prins JB, Sanders L, et al. Depot-related gene expression in human subcutaneous and omental adipocytes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1384–91. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J, Hegele RA. HIV-associated dyslipidaemia: pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:787–96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynisdottir S, Dauzats M, Thorne A, et al. Comparison of hormone-sensitive lipase activity in visceral and subcutaneous human adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:4162–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schambelan M, Benson CA, Carr A, et al. Management of metabolic complications associated with antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection: recommendations of an international AIDS society-USA panel. JAIDS. 2002;31:257–75. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200211010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza SA, Chow DC, Walsh E, et al. 2002. A 36-week safety and tolerability study of extended-release niacin (ERN) for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia (HT) in subjects with HIV [abstract] Fourth international workshop on adverse drug reactions and lipodystrophy in HIV, San Diego, CA, September 2002. Abstract 49. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Lovejoy JC, Greenway F, et al. Contributions of total body fat, abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments, and visceral adipose tissue to the metabolic complications of obesity. Metabolism. 2001;50:425–35. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.21693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]