Abstract

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common chronic rheumatic disease in children and an important cause of short-term and long-term disability. Gene changes in the immune system can predispose to JIA and regulation of the immune system is crucial in the pathogenesis. The goal of therapy is complete disease control using disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS). Activated T-cells may play a role in the immunopathology of JIA. Therefore, targeting T-cell activation is a rational approach for the treatment of JIA. Abatacept (ABA), a selective co-stimulation modulator, has been shown to be effective in treating all JIA subtypes and is generally safe and well tolerated in JIA. Neutralizing antibodies were found in 6/9 (67%) of seropositive patients, but anti-ABA antibodies did not appear to be associated with disease flare, serious adverse events, acute infusional adverse events, hypersensitivity, autoimmune disorders, or low ABA serum concentrations. Anti-ABA antibodies were more frequent when ABA concentrations were below therapeutic levels. Although information on ABA in JIA is still limited, available data suggest a potential role in difficult to treat JIA patients previously treated with other biologic agents and for non-responders to TNF-blockade.

Keywords: abatacept, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), biologics

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common chronic rheumatic disease in children and an important cause of short- and long-term disability in childhood. The incidence of JIA in Europe and North America is estimated to be 10 to 19 cases per year for every 100,000 children (Andersson Gare 1999). JIA is not a single disease but encompasses all subtypes of idiopathic arthritis in childhood with disease onset prior to age 16, and persistence for more than 6 weeks (Ravelli and Martini 2007). The 2004 International League of Associations for Rheumatalogy (ILAR) classification differentiates 7 distinct JIA subtypes: systemic arthritis, oligoarthritis (persistent oligoarthritis, extended polyarticular), polyarthritis rheumatoid factor (RF) positive, polyarthritis RF negative, psoriatic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, and undifferentiated arthritis (Petty et al 2004) (Table 1).

Table 1.

International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) classification for Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

| Classification | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Systemic arthritis | Arthritis in one or more joints, onset with fever, rash, or other systemic symptoms |

| Oligoarthritis | Arthritis affecting 1 to 4 joints for the first months of disease |

| Persistent oligoarthritis | |

| Extended polyarticular | |

| Polyarthritis | Arthritis affecting 5 or more joints in the first 6 months of disease; negative rheumatoid factor |

| Rheumatoid factor negative | |

| Polyarthritis | Arthritis affecting 5 or more joints in the first 6 months of disease; positive rheumatoid factor |

| Rheumatoid factor positive | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Psoriasis in child or first degree relative, or dactylitis, nail pitting, oncholysis |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | HLA-B27 related; formerly called spondylarthropathy |

| Undifferentiated arthritis | Arthritis that fulfills criteria in no categories or in 2 or more of the above categories |

Derived from Petty 2004.

Treatment of JIA has changed fundamentally over the past 20 years. Less toxic and more efficacious therapies including methotrexate (MTX) and leflunomide were introduced for the treatment for JIA. Novel technologies and ground-breaking basic science research in immunology have identified key factors involved in inflammation in JIA. These immune mediators and cell surface receptors are novel targets in children with refractory disease.

Pathophysiology of JIA

The etiology of JIA remains poorly understood. Both genetic and environmental factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of JIA (Ravelli and Martini 2007). A single causative gene defect for all JIA subtypes appears very unlikely, since the distinct clinical entities are minimally overlapping. A genome-wide scan in affected families suggested that several genes are associated with the development of JIA (Thompson et al 2004).

Susceptibility to JIA, and incidence and disease severity were shown to vary among ethnicities. Genetic polymorphisms of cytokines and their receptors may predispose for disease susceptibility. Distinct single-nuclear polymorphisms (SNPs) were found in systemic JIA patients, suggesting a pivotal role for mutations in regulatory elements of cytokine genes such as IL-6 (Fishman et al 1998; De Benedetti et al 2003).

Adaptive immune system

Both the innate and the adaptive immune system are important in the pathogenesis of JIA. Certain HLA-DR patterns are associated with particular JIA subtypes, suggesting a central role for the adaptive immune system in the etiology of JIA (Gattorno et al 2005; Martini et al 2005).

Populations of highly activated, possibly autoreactive T-cells can be detected in the synovium of JIA patients, suggesting a possible regulatory T-cell defect. Regulatory T-cells (Tregs) were shown to prevent the expansion of autoreactive T-cells. Children with oligoarticular JIA and long symptom-free intervals were found to have higher proportions of both synovial and peripheral Tregs (de Kleer et al 2004). The intracellular transcription factor FOXP3 is a characteristic marker of Tregs. FOXP3 expression is detectable in 40% of peripheral T cells in JIA patients. Higher levels of FOXP3 positive Tregs in the peripheral blood and synovial fluid of children with oligo JIA were shown to be associated with a more favorable disease course (de Kleer et al 2004).

B-cells are also important in JIA, as indicated by positive antinuclear antibody titers. In JIA, high B-cell numbers were found in the inflammatory synovial infiltrate (Gregorio et al 2007). Faber et al (2006) demonstrated a characteristic receptor editing of synovial B-cells.

Innate immune system

Major advances have been made towards understanding the actions of the innate immune system in inflammation. Distinct molecular activation patterns, the pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) and damage associated molecular pattern (DAMPS) were recently characterized (Fall et al 2007). PAMPS and DAMPS both bind to pattern recognition receptors. The activation of the inflammatory cascade might play an essential role in the pathogenesis of JIA. Distinct activation molecular patterns were more commonly found in children with systemic JIA (Fall et al 2007). The inflammasome is a protein complex present in macrophages and neutrophilic granulocytes. PAMPS and DAMPS have been shown to activate the inflammasome ultimately leading to activation of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Mutations of genes coding structures within the inflammasome are suggested to be a possible cause of systemic onset JIA (Woo et al 2005; Yokota et al 2005; Lequerre et al 2008). Infections can trigger flares in JIA possibly through PAMPS (Massa et al 2002).

Pro-inflammatory cytokines play a central role in JIA, which is also reflected in the efficacy and use of biologic agents. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonists are used in RF negative polyarthritis and blockers of IL-1 and IL-6 are used in systemic JIA (Woo et al 2005; Yokota et al 2005; Lequerre et al 2008).

Treatment of JIA

The treatment of JIA is specifically targeted to each JIA subtype. The management of JIA encompasses pharmacological interventions, physical and occupational therapy, and also psychosocial support (Ilowite 2002; Hashkes and Laxer 2005).

The aim of JIA treatment is to achieve disease control, preserve the physical and psychological integrity of the child, and to prevent any long-term sequelae of disease or therapy.

Prior to 1990, JIA treatment was based on the pyramid approach, initially using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids and gradually advancing to DMARDS. However, recent studies have indicated that previous assumptions on the benign course and outcome of JIA were incorrect. Radiological joint damage was thought to occur late in the disease course only. In fact, Wallace and Levinson reported that most children with systemic arthritis and polyarthritis have evidence of radiological joint damage within 2 years of disease (Wallace and Levinson 1991; Levinson and Wallace 1992). In a review on the medical treatment of JIA, Hashkes and Laxer (2005) found that most children never achieve a long-term remission, and concluded that the burden of disease to the patient, family, and society is large.

Subsequently, the JIA treatment paradigms changed: health care providers treat JIA patients earlier and consider novel, biologic therapy options in order to achieve disease control and prevent damage.

Standard therapy in JIA

The pharmacological treatment of JIA includes antiinflammatory and immuno-modulatory medications plus additional corticosteroid joint injections. None of these available drugs is thought to have curative potential (Hashkes and Laxer 2005).

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are commonly first-line therapy for JIA patients. They are considered a symptomatic treatment option, reducing pain, morning stiffness, and fever associated with systemic arthritis. Only in a minority of patients with oligoarthritis are NSAIDs alone sufficient to control the disease (Giannini and Cawkwell 1995).

MTX and leflunomide

Since its introduction in the early 1990s, MTX remains the treatment cornerstone for most children with polyarthritis (Niehues et al 2005). In systemic JIA, MTX seems to be less effective (Niehues et al 2005; Hashkes and Laxer 2006). Leflunomide is the alternative to MTX. It has been shown to produce similar response rates in patients with polyarticular JIA. Leflunomide is an option for patients who fail MTX or discontinue MTX because of side effects (Silverman et al 2005).

Novel biologic therapies

With the introduction of biologics, the treatment options for JIA have changed and improved markedly (Hashkes and Laxer 2006). Biologics are genetically engineered drugs that work by either selectively blocking the effects of cytokines or interfering with biological pathways directly and affecting immunologic effectors.

Cytokines are important signaling molecules that orchestrate host defense. They may act pro- or anti-inflammatory (Wilkinson et al 2003). Currently only the TNF blockers etanercept and adalimumab have been approved in many countries for the treatment of refractory, polyarticular JIA in children age 4 to 17 years. Controlled and uncontrolled studies provide consistent evidence on the general efficacy of etanercept in JIA. TNF blockade also seems to be highly effective in enthesitis-related arthritis and polyarthritis but less effective in patients with systemic arthritis (Kimura et al 2005; Hashkes and Laxer 2006).

However, several biologics have also been linked to rare but severe adverse events such as lymphoma, serious infections, demyelinations, and hepatotoxiticity (Gartlehner et al 2006).

Limitation of standard therapy

About 50% of children with JIA do not achieve remission despite treatment and require further rheumatological care as adults (Minden et al 2000). Treatment-resistant courses of JIA result in joint destruction and growth retardation, which lead to major functional limitations. Specifically, patients with polyarticular onset have the poorest prognosis, with a remission rate of only 15% over 10 years (Minden et al 2000). Therefore development of new approaches and evaluation of new therapeutic options are warranted. In addition to blocking the action of cytokines, targeting T-cell function is a promising approach. While T-cell depletion by anti-CD4 therapy was not effective in JIA (Horneff 1995), modulation of T-cell function may have a therapeutic impact.

Targeting T-cells in JIA as a therapeutic option

There is increasing evidence suggesting that activated T-cells may play a fundamental role in the immunopathology of JIA either by directly influencing other cell types through cell-to-cell contact or by producting immunomodulatory cytokines (Niehues et al 2008). One of the initial steps in T-cell activation is antigen recognition through the T-cell receptor. Following antigen recognition, T-cells require co-stimulation to become fully activated. One of the best-characterized costimulatory pathways is the engagement of CD 80/CD86 on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) with CD 28 on T-cells (Figure 1a). This produces a positive costimulatory signal and promotes full T-cell activation (Smolen and Steiner 2003). While naive T-cells are classically thought to be more dependent on a costimulatory signal than activated T-cells, there is evidence that autoimmune effector T-cells also require a costimulatory signal for their maintenance (Schweitzer and Sharpe 1998; Chang et al 1999). There are several very important pathways involved in T-cell activation, some of which optimize T-cell activity and some of which cause down-regulation. The most important ligand is CTLA-4, a well-defined down-regulator of T-cell activation, which has a much higher binding affinity for CD80/CD86 than CD28. Its expression is increased on the T-cell surface 24 to 48 hours after T-cell activation. Abatacept (ABA) is a novel biologic agent, targeting CD28/B7 interaction (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Abatacept modulates T-cell reaction by co-stimulation.

Focus of review

The focus of this review is to summarize available data on ABA targeting T-cells and its potential role in refractory JIA. A phase III multicenter, multi-national, randomized withdrawal study, which was performed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of ABA in children and adolescents with active juvenile rheumatoid arthritis/JIA (JRA/JIA), will be reviewed in detail (Ruperto et al 2008).

Abatacept-history

Abatacept or CTLA-4 Ig is a fully human, soluble recombinant fusion protein comprising the extracellular domain of human CTLA-4 and a fragment of the Fc- domain of human IgG-1, which has been modified to prevent complement fixation. ABA competes with the high binding avidity of CTLA-4 for CD80/CD86 on APCs to competitively bind CD80/CD86. This prevents these molecules from engaging CD 28 on T-cells and selectively modulates these costimulatory pathways, preventing full T-cell activation. ABA shows linear pharmakokinetic characteristics, only limited inter-individual variability, and has a serum-half-life of 14.7 days (Abrams et al 1999). ABA has been tested and has shown efficacy in preclinical studies involving many animal models of autoimmune disease (Finck et al 1994; Webb et al 1996) and allograft rejection (Lin et al 1993).

Abatacept in adult rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Efficacy and safety of ABA in the treatment of RA were first evaluated using ABA as monotherapy in a dose-finding pilot study in patients with active early RA refractory to DMARDS (Moreland et al 2002). It led to a dose-dependent response as measured by percentages of RA patients meeting the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20% improvement criteria. A subsequent phase IIb trial compared combination therapy of ABA plus methotrexate (MTX) with MTX alone in patients with active RA. Combination therapy effectively controlled the signs and symptoms of RA and improved patients’ physical function and health-related quality of life. Trials in adult RA have shown that ABA induces improvement in disease and health-related quality of life, and inhibits progression of structural damage in patients who did not respond to other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or anti-TNF therapy (Kremer et al 2003, 2006). A 2-year follow up of RA patients with difficult-to-treat disease showed sustained improvement of signs and symptoms of RA, physical function, and health-related quality of life after 6 months (Genovese et al 2008).

Weinblatt et al (2006) reported that the combination of ABA and etanercept in RA patients was associated with an increase in serious adverse events (SAEs) with only limited clinical benefit. Subsequently the authors advised against the use of ABA in combination with etanerecpt for the treatment of RA (Weinblatt et al 2007).

Abatacept in JIA

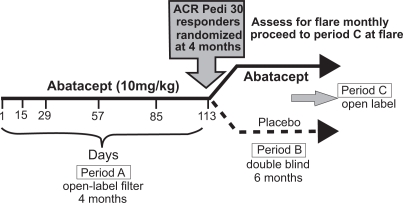

A randomized controlled trial of ABA in JIA (Ruperto et al 2008) was a phase III, double-blind, randomized, controlled withdrawal trial in children with JIA including extended oligoarticular, polyarticular, positive or negative for rheumatoid factor, or systemic JIA without systemic manifestations. The aim of the study was to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept compared with placebo in children, who had active JIA and either inadequate response, or intolerance to at least one DMARD, including some patients who had failed anti-TNF therapy. The study included children ages 6 to 17 years, with current active arthritis in at least 5 joints, 2 with limitation of motion and failure to treatment with at least 1 DMARD including biologic therapy. All patients received ABA 10 mg/kg to a maximum of 1000 mg (iv infusion) on day 1, 15, and every 28 days thereafter in the 4-month open-label (OL) lead-in period. MTX was permitted at a dosage of 10 to 30 mg/m2/week and prednisone at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg/day. At the end of the OL lead-in period (day 113), response was assessed by ACR pediatric improvement criteria (ACR Pedi) 30, 50, 70, and 90. All ACR Pedi 30 responders were eligible for randomization. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either ABA 10 mg/kg or placebo for 6 months (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study design of the randomized double-blinded withdrawal trial of abatacept versus placebo for children with polyarticular course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) Adapted from Giannini et al 2006.

The primary endpoint was time to JIA flare defined as worsening of 30% or more in at least 3 of the 6 ACR core-response variables for JIA, and at least 30% improvement in no more than 1 variable during the double-blind period (Brunner et al 2002). Secondary objectives included the proportion of patients who had disease flare; the changes from baseline in each of the 6 ACR core variables; and assessment of safety and tolerability.

OL phase

A total of 190 patients with JIA were enrolled (Period A), 77% were Caucasian; 72% were female; the mean age was 12.4 years. Distribution of JIA subtypes: 64% were polyarticular JRA/JIA (20% RF positive), systemic JRA/JIA in 20%, extended oligoarticular in 14%, and surprisingly persistent oligoarticular JRA/JIA in 2%. Limited information is provided about the choices and duration of previous therapies. A total of 30% were previously treated with anti-TNF therapy, which was most commonly discontinued for lack of efficacy in 27%. Concomitant MTX was given to 74% of patients (140/190) at a mean dose of 13 mg/m2/week, similar in both groups.

Randomized phase

The lead-in period was completed by 170 patients (89%), of which 123 were responders (ACR Pedi 30 improvement) and 122 patients were randomized. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between the treatment group and placebo controls. The rates of ACR Pedi 30 responders were similiar across the subtypes of JIA: polyarticular–RF positive (26/38, 68%); polyarticular–RF negative (54/84, 64 %); systemic (24/37, 65%); oligoarticular extended (16/27, 59.3%); and persistent oligoarticular 2/2.

Outcome

Flare rate

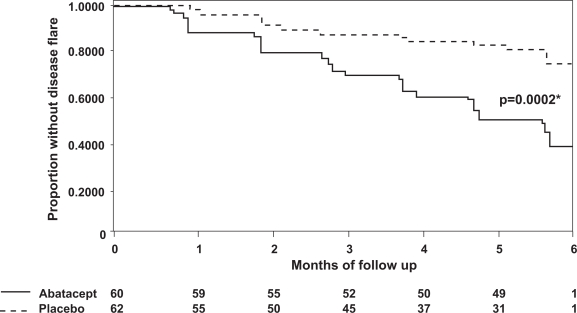

A significantly higher flare rate was observed in placebo-treated patients than ABA-treated patients over 6 months. A total of 33/62 (53%) placebo-treated patients flared and were switched to open-label ABA. In contrast, only 12/60 (20%) ABA-treated patients flared (p = 0.002, Figure 3). In the ABA group, 49/60 completed the 6-month randomized phase, whereas only 31/62 placebo treated children did. Unfortunately, no information is provided about the JIA subtypes that either had sustained responses or disease flares.

Figure 3.

Flare-free survival of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) treated with either abatacept or placebo. The graph demonstrates the proportion of patients without disease flare during the 6-month double-blind period. P value represents the comparison of the time to disease flare between the abatacept and placebo groups. Adapted from The Lancet, 372, Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization; Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. 2008. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial, 383–91, Copyright © 2008 with permission from Elsevier.

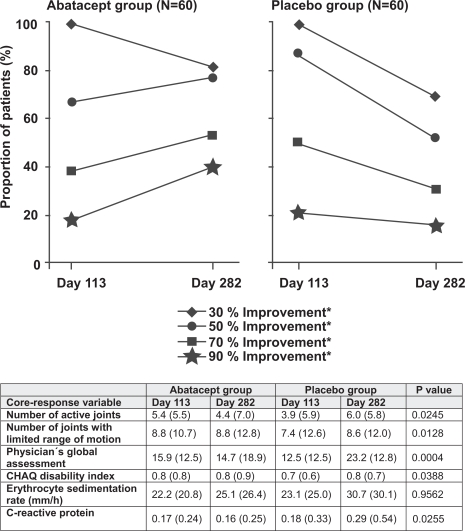

ACR pediatric 30, 50, 70 responses

In the open label phase, ABA was efficacious in patients of all JIA subtypes. In the randomized phase the overall ACR pediatric 30 response rate was not significantly different between ABA and placebo (82% for ABA vs 67% for placebo; p = 0.17). The ACR pediatric 50 response rate was significantly different (77% for ABA vs 52% for controls; p = 0.007). ACR pediatric 70 rate were also significantly different (53% for ABA vs 31% for controls p = 0.019). Within the ACR pediatric core set the number of active joints (ABA: 5.4–4.4 at 6 months, placebo 3.9–6.0 at 6 months), the number of joints with limited range of motion (ABA 8.0–8.0, placebo 7.4–8.6 at months), physician global assessments scale, the Child Health Assessment Questionnaire, and C-reactive protein showed statistically significant differences between the groups at 6 months. In contrast patient-derived measures and erythrocyte sedimentation rate did not differ between treatment and control groups (Figure 4). The distribution of response among JIA subtypes is not reported in the publication.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of abatacept: Rate of responders during the double-blinded withdrawal of abatacept versus placebo in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Adapted from The Lancet, 372, Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization; Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. 2008. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial, 383–91, Copyright © 2008 with permission from Elsevier.

Safety

Adverse events were reported in 70% of abatacept-treated patients during the open-label period and in 62% in the double-blind period. Mild infusion reactions were seen in 4%. During the lead-in period 6 patients had serious adverse events; 3 were related to the underlying JIA. The others were varicella zoster infections, ovarian cysts, and acute lymphocytic leukemia. The safety data are summarized in Table 2 (Ruperto et al 2008).

Table 2.

Adverse events in juvenile idiopathic arthritis ( JIA) patients treated with either abatacept or placebo

| 4-month open-label period | 6-month double-blind period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abatacept (N = 190) | Abatacept (N = 60) | Placcbo (N = 62) | p value* | |

| Total serious adverse events | 6 (3%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0.50 |

| Total adverse events† | 133 (70%) | 37 (62%) | 34 (55%) | 0.47 |

| Infections and infestations | 68 (36%) | 27 (45%) | 27 (44%) | 1.00 |

| Influenza | 7 (4%) | 5 (8%) | 4 (7%) | 0.74 |

| Bacteriuria | 3 (2%) | 4 (7%) | 0 | 0.06 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 11 (6%) | 4 (7%) | 3 (5%) | 0.72 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 14 (7%) | 4 (7%) | 5 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 (0.5%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0.36 |

| Sinusitis | 6 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 0.68 |

| Rhinitis | 8 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (7%) | 0.36 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 66 (35%) | 10 (14%) | 9 (15%) | 0.81 |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0.36 |

| Nausea | 19 (10%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (7%) | 0.68 |

| Diarrhea | 17 (9%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.00 |

| Upper abdominal pain | 10 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0.49 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 26 (14%) | 4 (7%) | 9 (15%) | 0.24 |

| Pyrexia | 12 (6%) | 4 (7%) | 5 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Nervous system disorders | 30 (16%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 0.68 |

| Headache | 25 (13%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0.36 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 32 (17%) | 6 (10%) | 3 (5%) | 0.50 |

| Cough | 17 (9%) | 0 | 2 (3%) | 0.50 |

*Fisher’s test used to test the difference between groups given abatacept and placebo in the double-blind phase.

Adverse events that occurred in at least 5% of patients in the open-label and double-blind phases.

Adapted from The Lancet, 372, Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization; Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. 2008. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial, 383–91, Copyright © 2008 with permission from Elsevier.

Immunogenicity of abatacept (Sigal et al 2007)

ABA-specific antibodies against the entire ABA molecule or the CTLA-4 portion were measured by ELISA. Specificity of antibodies was defined using a competition assay. Neutralizing activity was evaluated in a cell-based bioassay. Of the 188 patients evaluated in the trial, 40 (21.3%) were seropositive at least once, 1.2% (2/162) had ABA-specific antibodies, 20.7% (39/188) had anti-CTLA-4-specific antibodies, and 1 patient had both. Most patients did not have antibodies at 2 or more consecutive visits. Seropositivity did not appear to be associated with disease flare, SAE, acute infusional AE, hypersensitivity, autoimmune disorders, or low through ABA serum concentrations. Anti-ABA-antibodies were more frequent when ABA concentrations were below therapeutic levels. Of seropositive patients evaluated, 6/9 (67%) had neutralizing antibodies.

Summary of phase III multicenter randomized withdrawal study

In this study, treatment with abatacept significantly reduced disease activity in JIA. After the lead-in open label phase, 65% (123/190) reached an ACR Pedi 30, 47% an ACR Pedi 50 (90/190), and 29% (55/190) an ACR Pedi 70. A significant difference was noted in responder rates between patients previously treated with biologic therapies and biologics-naive JIA patients. Responder-rates of biologics-naive JIA patients were twice as high as those seen in pre-treated JIA patients.

The enrichment design of the trial then only included ACR Pedi 30 responders into the randomized phase. At the end of the double-blinded randomized phase (day 169) the ACR pediatric 50 responder rate increased from 67% to 77% in the ABA group, while the rate decreased from 87% to 52% in the controls. Similarly the rate of ACR Pedi 70 responders further increased in the ABA group from 38% to 53%, while it dropped from 50% to 31% in controls (Figure 4) (Ruperto et al 2008).

ABA was generally safe and well tolerated. The overall incidence of AE was similar in the ABA and placebo groups. No discontinuation of therapy because of adverse events was noted. Antibodies to ABA were more frequently seen in patients with protocol-defined therapy interruption than in patients on continuous therapy. The transient seropositivity did not appear to be associated with decreased clinical efficacy. ABA-specific antibodies appeared to be of no clinical significance.

Conclusions

JIA is a common, chronic illness of childhood associated with major long-term disability. Basic science research advances have provided insights into the pathogenesis of JIA, identifying key factors and crucial mechanisms that perpetuate inflammation. T-cells play a pivotal role predominantly mediated through cell–cell interactions facilitated through co-stimulatory molecules such as CTLA-4 and its ligands.

Therapy of JIA has advanced substantially. With the introduction of MTX and leflunomide, two highly effective and less toxic DMARDS became available. TNF-alpha inhibitors increased the rate of children achieving disease control and remission on medication. Nevertheless, some patients do not respond to existing agents or may not be candidates for them, while others are unable to tolerate them.

Abatacept is the first of a novel class of therapies, the selective co-stimulation modulators. In the single pediatric trial available, ABA led to a 65% ACR Pedi 30 response rate despite including a highly selected population of severe polyarticular arthrits patients in the study. Children enrolled in the trial had previously failed TNF blockage and had ongoing disease activity despite concomitant DMARD therapy. These results suggest that abatacept could also be effective in patients who have failed previous treatment with anti-TNF agents. The safety profile was favorable. ABA may play an important role in the future treatment of children with refractory JIA primarily. Long-term studies are needed to assess sustained efficacy and safety of this novel therapy for JIA.

Abbreviations

- ABA

abatacept

- ACR

American College of Rheumatology

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- DAMP

damage associated molecular pattern

- DB

double blind

- DMARDS

disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- IL

interleukin

- ILAR

International League of Associations for Rheumatology

- JIA

juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MTX

methotrexate

- NLR

NOD proteins containing leucine-rich repeats

- NOD

nucleotide oligomerisation domain

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OL

open label

- PAMP

pathogen associated molecular pattern

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation endproducts

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- SAE

serious adverse event

- SNPs

single-nuclear polymorphisms

- TLR

toll-like receptors

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- Tregs

regulatory T-cells

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Abrams JR, Lebwohl MG, Guzzo CA, et al. CTLA4Ig-mediated blockade of T-cell costimulation in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1243–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Gare B. Juvenile arthritis – who gets it, where and when? A review of current data on incidence and prevalence. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:367–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner HI, Lovell DJ, Finck BK, et al. Preliminary definition of disease flare in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1058–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Shevach EM, Segal BM. Regulation of interleukin (IL)-12 receptor beta2 subunit expression by endogenous IL-12: a critical step in the differentiation of pathogenic autoreactive T cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:969–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. BMS-188667 in children and adolescents with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00095173?order=16

- De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Vivarelli M, et al. Functional and prognostic relevance of the –173 polymorphism of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene in systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1398–407. doi: 10.1002/art.10882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kleer IM, Wedderburn LR, Taams LS, et al. CD4+CD25bright regulatory T cells actively regulate inflammation in the joints of patients with the remitting form of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Immunol. 2004;172:6435–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber C, Morbach H, Singh SK, et al. Differential expression patterns of recombination-activating genes in individual mature B cells in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1351–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.047878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall N, Barnes M, Thornton S, et al. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood from patients with untreated new-onset systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis reveals molecular heterogeneity that may predict macrophage activation syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3793–804. doi: 10.1002/art.22981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck BK, Linsley PS, Wofsy D. Treatment of murine lupus with CTLA4Ig. Science. 1994;265:1225–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7520604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman D, Faulds G, Jeffery R, et al. The effect of novel polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene on IL-6 transcription and plasma IL-6 levels, and an association with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1369–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foell D, Wittkowski H, Roth J. Mechanisms of disease: a ‘DAMP’ view of inflammatory arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:382–90. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Jonas BL, et al. The comparative efficacy and safety of biologics for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2398–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattorno M, Prigione I, Morandi F, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterisation of CCR7+ and CCR7- CD4+ memory T cells homing to the joints in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R256–67. doi: 10.1186/ar1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese MC, Schiff M, Luggen M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the selective co-stimulation modulator abatacept following 2 years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:547–54. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.074773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini EH, Ruperto N, Prieur AM, et al. 2006Efficacy and safety of abatacept in children and adolescents with active juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): results of double-blind withdrawal phase [abstract] Presented at American College of Rheumatology Annual Scientific Meeting 2006Washington, DCNovember10–15Abstract L2(482). [Google Scholar]

- Giannini EH, Cawkwell GD. Drug treatment in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Past, present, and future. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42:1099–125. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)40055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio A, Gambini C, Gerloni V, et al. Lymphoid neogenesis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis correlates with ANA positivity and plasma cells infiltration. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:308–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashkes PJ, Laxer RM. Medical treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. JAMA. 2005;294:1671–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.13.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashkes PJ, Laxer RM. Update on the medical treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006:8450–8. doi: 10.1007/s11926-006-0041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilowite NT. Current treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics. 2002;109:109–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Pinho P, Walco G, et al. Etanercept treatment in patients with refractory systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:935–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JM, Westhovens R, Leon M, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T-cell activation with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1907–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JM, Genant HK, Moreland LW, et al. Effects of abatacept in patients with methotrexate-resistant active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med J. 2006;144:865–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequerre T, Quartier P, Rosellini D, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) treatment in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or adult onset Still disease: preliminary experience in France. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:302–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson JE, Wallace CA. Dismantling the pyramid. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1992;33:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Bolling SF, Linsley PS, et al. Long-term acceptance of major histocompatibility complex mismatched cardiac allografts induced by CTLA4Ig plus donor-specific transfusion. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1801–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini G, Zulian F, Calabrese F, et al. CXCR3/CXCL10 expression in the synovium of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R241–9. doi: 10.1186/ar1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa M, Mazzoli F, Pignatti P, et al. Proinflammatory responses to self HLA epitopes are triggered by molecular mimicry to Epstein-Barr virus proteins in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2721–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minden K, Kiessling U, Listing J, et al. Prognosis of patients with juvenile chronic arthritis and juvenile spondyloarthropathy. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2256–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JA, Paul-Clark MJ, Clarke GW, et al. Critical role of toll-like receptors and nucleotide oligomerisation domain in the regulation of health and disease. J Endocrinol. 2007;193:323–30. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland LW, Alten R, Van den Bosch F, et al. Costimulatory blockade in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot, dose-finding, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating CTLA-4Ig and LEA29Y eighty-five days after the first infusion. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1470–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehues T, Feyen O, Telieps T. [Concepts on the pathogenesis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis] Z Rheumatol. 2008;67:111–6. 118–20. doi: 10.1007/s00393-008-0276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehues T, Horneff G, Michels H, et al. Evidence-based use of methotrexate in children with rheumatic diseases: a consensus statement of the Working Groups Pediatric Rheumatology Germany (AGKJR) and Pediatric Rheumatology Austria. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:169–78. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization; Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Lancet. 2008;372:383–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60998-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer AN, Sharpe AH. Studies using antigen-presenting cells lacking expression of both B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) show distinct requirements for B7 molecules during priming versus restimulation of Th2 but not Th1 cytokine production. J Immunol. 1998;161:2762–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal LH, Manning J, Sinisi S, et al. Immunogenicity of abatacept during a double-blind randomized withdrawal study in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) ACR Abstract 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Silverman E, Mouy R, Spiegel L, et al. Leflunomide or methotrexate for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1655–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen JS, Steiner G. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:473–88. doi: 10.1038/nrd1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SD, Moroldo MB, Guyer L, et al. A genome-wide scan for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in affected sibpair families provides evidence of linkage. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2920–30. doi: 10.1002/art.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace CA, Levinson JE. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: outcome and treatment for the 1990s. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1991;17:891–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb LM, Walmsley MJ, Feldmann M. Prevention and amelioration of collagen-induced arthritis by blockade of the CD28 co-stimulatory pathway: requirement for both B7-1 and B7-2. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2320–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinblatt M, Combe B, Covucci A, et al. Safety of the selective costimulation modulator abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving background biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: A one-year randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2807–16. doi: 10.1002/art.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinblatt M, Schiff M, Goldman A, et al. Selective costimulation modulation using abatacept in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis while receiving etanercept: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:228–34. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson N, Jackson G, Gardner-Medwin J. Biologic therapies for juvenile arthritis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:186–91. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P, Wilkinson N, Prieur AM, et al. Open label phase II trial of single, ascending doses of MRA in Caucasian children with severe systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: proof of principle of the efficacy of IL-6 receptor blockade in this type of arthritis and demonstration of prolonged clinical improvement. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R1281–8. doi: 10.1186/ar1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S, Miyamae T, Imagawa T, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of humanized recombinant anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody in children with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:818–25. doi: 10.1002/art.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]