Abstract

The expression of heat-shock protein 60 (also known as chaperonin 60, Cpn60) in experimental acute pancreatitis (AP) is considered to play an active role in the prevention of abnormal enzyme accumulation and activation in pancreatic acinar cells. However, there are controversial results in the literature regarding the relationship between the abnormality of Cpn60 expression and AP onset and development. The purpose of this study was to investigate the alternations of Cpn60 expression and the relationship between the abnormal expression of Cpn60 and AP progression in rat severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) models. In this report, we induced SAP in Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats by reverse injection of sodium deoxycholate into the pancreatic duct, and examined the dynamic changes of Cpn60 expression in pancreatic tissues from different time points and at different levels with techniques of real-time PCR, western blotting, and immunohistochemistry. At 1 h after SAP induction, the expression of Cpn60 mRNA in the AP pancreatic tissues was higher than those in the sham-operation group and normal control group, but decreased sharply as the time period was extended, and there was a significant difference between 1 h and 10 h after SAP induction (p < 0.05). In the AP process, Cpn60 protein expression showed transient elevation as well, and the increased protein expression occurred predominantly in affected, but not totally destroyed, pancreatic acinar cells. As AP progressed, the pancreatic tissues were seriously damaged, leading to a decreased overall Cpn60 protein expression. Our results show a complex pattern of Cpn60 expression in pancreatic tissues of SAP rats, and the causality between the damage of pancreatic tissues and the decrease of Cpn60 level needs to be investigated further.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, Chaperonin 60 (Cpn60), Pancreatic tissue, Experimental study

Introduction

Heat-shock proteins (HSPs) are a group of highly conserved proteins; and in a number of cases, they can be stimulated by stress to initiate or to boost production. HSPs not only constitute the important component of the cell response to stress, but also participate in a variety of physiological functions of the cell, such as participation in protein synthesis, degradation, folding, and transport (Deocaris et al. 2006; Horwich et al. 2001; Lu and Li 2007). HSP60, also known as chaperonin 60 (Cpn60), a molecular chaperone in the HSPs family, is encoded by nuclear genes, and mainly functions to assist newly formed peptides to fold or assemble correctly (Levy-Rimler et al. 2002; Schafer and Williams 2000).

In normal pancreatic tissue, Cpn60 is expressed to a certain extent. It not only exists in the mitochondria of pancreatic acinar cells, but also presents in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), in Golgi body (G), in zymogen granules (ZG), and in the secretory pathway of pancreatic enzymes in acinar cells (Li et al. 2003; Cechetto et al. 2000). It is thought that Cpn60 residing in the mitochondria plays a different role from that of the protein located in the RER–G–ZG (Soltys and Gupta 2000; Keskin et al. 2002). Studies have found that along the secretory pathway, there is a quantitative correlation between Cpn60 and pancreatic enzymes such as lipase, amylase, and trypsin (Bruneau et al. 2000; Li et al. 2003).

Moreover, studies reported that the induced high expression of Cpn60 by a variety of experimental methods offered a certain degree of protection for pancreatic tissues and reduced the inflammation in the pancreas (Takacs et al. 2002; Hennequin et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2000). However, due to the variety of replication methods for the acute pancreatitis (AP) animal model, the pathogenesis varies, as do the changes of HSPs and Cpn60 (Ethreidge et al. 2000; Rakonczay et al. 2002a; Tashiro et al. 2002; Krueger et al. 2001). In our earlier work, we found that in the severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) rat model induced by retrograde injection of sodium deoxycholate into the pancreatic duct, the amount of Cpn60 protein was significantly lower in the RER, Golgi, and ZG of pancreatic acinar cells at 5 h after SAP replication, while the levels of pancreatic chymotrypsin and lipase remained high. We hypothesized that Cpn60 may have an important protective function during the AP process, and the resultant imbalance between the pancreatic enzymes and Cpn60 may play a role in the intracellular activation of the enzymes and digestive damage of pancreatic tissues (Li et al. 2003; Li and Bendayan 2005). These fresh but controversial results have prompted interest in further studies on the relationship between Cpn60 expression and AP onset and development. Here, we replicated SAP in rats and observed the expression of Cpn60 in rat pancreatic tissue from different time points and at different levels, using procedures of real-time PCR, immunohistochemistry, and western blotting, with the objective to investigate the alternations of Cpn60 expression and the possible relationship between the abnormal expression of Cpn60 and AP progression in rat SAP models.

Materials and methods

Animals

Sixty-three Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (220–250 g each) of both sexes were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Fudan University (Shanghai, China). The animals were housed for 1 week under standard conditions with free access to water and lab chow. Prior to the experiment, the rats fasted overnight with only water allowed, and were randomly divided into a SAP group (n = 27), a sham-operated group (sham, n = 27) and a normal control group (control, n = 9). The experimental procedures for rats below were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Tongji University, Shanghai, China. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals in the experiments.

The experimental models were prepared as follows: SAP models were replicated based on a slightly modified procedure of the method reported by Li et al. (2003). Under aseptic conditions, the rats were injected intraperitoneally with 3% sodium pentobarbital for anesthesia (0.1 ml/100 g body weight). The abdominal cavity of the rats was then opened with a 3-cm epigastric median incision, and 3% sodium deoxycholate (0.1 ml/100 g body weight) was retrogradely injected via the pancreatic-duct opening at the duodenum into the pancreas with injection velocity 0.2 ml/min. Meanwhile, the common bile duct was clipped near the hepatic portal. After the injection, the point of injection was pressed for 1–2 min to avoid bleeding and leakage, followed by a lifting of the blocked bile duct and a stratified closing of the abdominal incision. The rats in the sham group proceeded with the same surgery procedure but without the retrograde injection of sodium deoxycholate.

Tissue collection

At 1-, 5-, 10-h intervals after the surgery, nine rats from the SAP group and the sham group, and nine normal rats were sacrificed with overdosed anesthetics (the nine normal rats were sacrificed together with the rats of 1 h SAP group). The tail part of the pancreas was quickly removed from each rat through the abdominal incision and used in the following experiments: routine pathological examination, real-time PCR, western blot, and immunohistochemical detection for Cpn60 expression. The blood samples from rats were collected by cardiac puncture and centrifuged, and the serum samples were used for amylase assay.

Measurement of amylase activity in serum

The assay of amylase activity in the samples of the serum was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol of the amylase assay kit (Jiancheng Technology, China).

Pathological examination

The pancreatic tissue was fixed in 10% formalin, freeze-sliced, paraffin-embedded, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE staining). The slides were observed under a light microscope for pathological changes, and scored for semi-quantitative assessment using reported literature (Schmidt et al. 1992).

Real-time PCR detection of Cpn60 mRNA expression

After removal from the rats, the pancreatic tissues were immediately put into a homogenizer filled with liquid nitrogen and ground into white powders while fresh liquid nitrogen was continuously added in order to minimize the RNA degradation. Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) was then added (approximately 75 mg tissue per milliliter Trizol) and total RNA was extracted from these homogenized tissues following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. The RNA was then measured on a spectrophotometer for purity and quantity, and electrophoresed on formaldehyde agarose gel for integrity. Total RNA (3 µg each) from every RNA preparation was used as a template for reverse transcription to cDNA with Reverse Transcription System (Promega, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommended procedure, with the addition of primer. Since mRNAs in pancreatic tissues, especially during pancreatitis, are extremely vulnerable for degradation, 0.7 µl oligo dT plus 0.3 µl random primer were used such that partially degraded mRNA might be reverse-transcribed as well.

After completion of the reverse transcription reaction, the cDNA reaction mixture was diluted 100 times, and applied in real-time PCR using SYBR Primix Ex TaqTM Kit (Takara, Japan). The real-time PCR reaction contained diluted cDNA template, 10 μl, 2× reaction mixture, 12.5 μl, Cpn60 primer mixtures 1 μl (10 pmol each primer; Invitrogen, USA), with DEPC-treated H2O added to total volume of 25 μl. Reactions were performed in a Quantitative PCR Instrument (Rotor Gene™, USA) with a “hot start” program: 95°C × 10 s incubation; followed by 40 cycles 95°C × 5 s, 60°C × 15 s, 72°C × 15 s. GAPDH was included in each reaction as an internal standard. Cpn60 forward primer sequence was 5′-ggctatcgctactggt-3′ and reverse primer 5′-gcaagtcgctcgttca-3′, resulting in a 237-bp amplicon fragment; GAPDH forward primer sequence was 5′-accacagtccatgccatcac-3′ and reverse primer 5′-tccaccaccctgttgctgta-3′, resulting in a 452-bp amplicon fragment. The relative expression of Cpn60 mRNA was represented as the percentage of normal control with the individual ratio of the Cpn60 amplified cycle threshold (CT) value against the respective GAPDH-amplified CT value.

The detection of Cpn60 protein expression by western blotting

One milliliter protein lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA, 1 μl/ml β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to some 100 mg pancreatic tissue on a homogenizer, and the tissue was triturated meticulously and left on ice for 1 h until completion of the lysis reaction. The lysis mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected and measured for protein content using Protein Quantitative Detection Kit (Bio-Rad, USA). An appropriate amount of protein was mixed with loading buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1% phenol blue), heated at 95°C for 5 min, and put on standby on ice. Samples (50 µg each) were then electrophoresed in 4–12% NuPAGE Novex Bis–Tris Gels (Invitrogen, USA) at 100 V until the dye phenol blue reached the bottom (about 50 min). The gel was then transferred by electroblotting to nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman, USA). After blotting was completed, the membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST for 1 h, incubated with anti-Cpn60 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:8,000 dilution; product number: SPA-829, Stressgen, Canada) at 4°C overnight, washed several times with 1× TBST, and incubated again with 1:3,000 horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immuno Co., USA) at room temperature for 1 h, TBST washed, and visualized with ECL reagent (Santa Cruz, USA). For internal reference, a monoclonal mouse anti-rat GAPDH antibody (1:5,000 dilution; Abcam, UK) was used. Gel-Pro analyzer 4.0 image analysis system (Chuangmei Co., China) was applied for analysis of the optical density of the protein bands. The relative expression quantity of Cpn60 protein was illustrated as the percentage of the optical density (OD) of Cpn60, adjusted with the corresponding GAPDH OD versus that of the normal control.

The in situ detection of Cpn60 protein expression by immunohistochemistry

Using the SP method, conventional paraffin sections with rat pancreatic tissues were dewaxed in water and microwave-heated for antigen repairing. One hundred microliters of 3% H2O2/methanol was added onto each slide and incubated for 30 min at room temperature to remove endogenous peroxidase activity. The slides were then blocked at 37°C with goat serum for 30 min in a humidified chamber, and the mouse anti-Cpn60 monoclonal antibody (1:1,000 diluted) was dropped onto the tissues and incubated overnight at 4°C. Biotin-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG working fluid 50 μl (Jinqiao Bio. Co. Ltd., China) was then applied onto each slide, and the slides were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by incubation with HRP-labeled streptavidin working solution 50 μl at 37°C for 30 min. There were at least three PBS rinses between incubations. Finally, slides were DAB-stained, and, after a complete tap-water rinse, were nuclear re-stained with hematoxylin, conventionally dehydrated, and mounted. In a negative control, PBS was used to replace the primary antibody.

Image analysis was accomplished by semi-quantification using digital Motic Med 6.0 image analysis system (Motic, Germany). Five non-overlapping views were selected from each slide for observation (100× amplification), and average optical density represented the positive staining intensity.

Statistical analysis

All data, represented by mean ± standard deviation, were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA; SPSS 12.0 software) unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was assessed as p < 0.05 (significant) or p < 0.01 (very significant).

Results

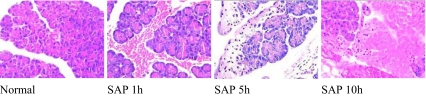

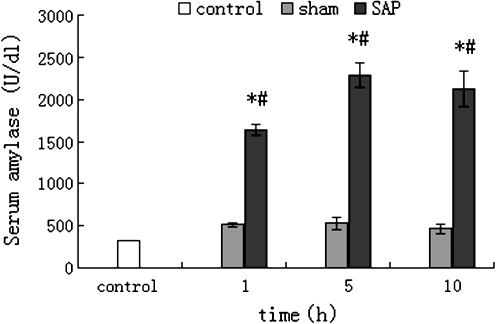

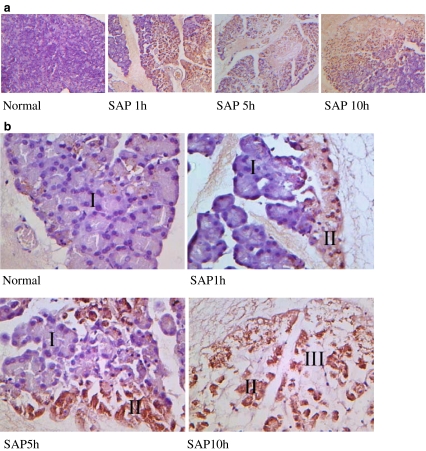

After 1 h of SAP development, the pancreatic acini of rats swelled to various degrees and the pancreatic tissues showed necrosis, bleeding, and inflammatory cell infiltration. These changes worsened as time passed. The pathological changes were graded at 1 h, 5 h, 10 h as 6, 10, 13 scores, respectively (Fig. 1). The parallel assay of amylase activity in SAP rat serum showed that, compared with that in normal control serum of rat and with that in sham groups, respectively, the enzyme activity increased significantly (p < 0.01), and, in the experimental observation period, sustained at high levels (Fig. 2). Taken together, these results indicated that the development of SAP in rats was successful

Fig. 1.

The pathological changes of pancreatic tissue in rat SAP model (HE, ×400). The pancreas of rats were removed at either 1, 5, or 10 h, fixed, paraffin-embedded, sliced, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for microscopic observation, as described in “Materials and methods”. The pancreatic acini of SAP rats swelled to various degrees and the pancreatic tissues showed necrosis, bleeding, and inflammatory cell infiltration. These changes worsened as time passed with pathological scores 6, 10, 13 at 1, 5, 10 h, respectively

Fig. 2.

Amylase activity in serum of rats (mean±SD, n = 9; U/dl). The amylase test was performed as described in the section of “Materials and methods”. The serum samples of rats were collected at 1, 5, and 10 h after SAP induction or sham operation, respectively; *p < 0.01 compared with normal control group, #p < 0.01 compared with sham group at the same time point

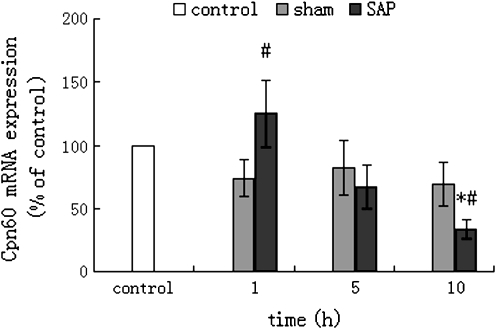

The change of Cpn60 mRNA expression in the pancreatic tissue of SAP rats showed that the Cpn60 mRNA expression in the SAP group increased significantly at the 1 h time point (p < 0.05), compared to that of the sham group at the same time point. However, as time elapsed, the Cpn60 mRNA expression decreased progressively in the 5 and 10-h SAP groups. The expression of Cpn60 mRNA in the 10-h SAP group was significantly lower, compared to that of the sham group at the same time point and that of the control group (p < 0.05). The expression of Cpn60 mRNA in the sham group at different time points decreased slightly compared to that of the control group, but the difference was of no statistical significance (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Expression of Cpn60 mRNA in rat pancreatic tissue by real-time PCR (mean±SD, n = 6). The total RNAs of rat pancreatic tissue were extracted using Trizol reagent and were used as templates for reverse transcription reactions into cDNA with Superscript™ II RT Kit, followed by real-time PCR using SYBR Primix Ex TaqTM kit. The relative expression of Cpn60 mRNA was represented as the percentage of normal control with the individual ratio of the Cpn60 amplified cycle threshold (CT) value against the respective GAPDH-amplified CT value; *p < 0.01 compared with normal control group; #p < 0.05 compared with sham group at the same time point

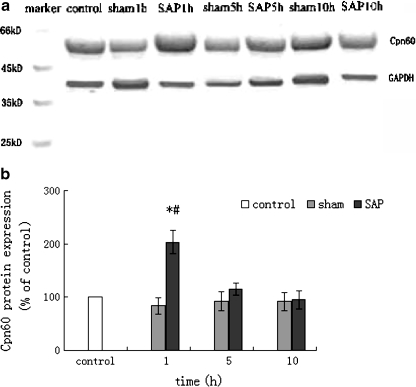

The protein expression of Cpn60 in the rat pancreatic tissue was shown in Fig. 4a and b. The amount of Cpn60 protein expression in the SAP group and sham groups was presented as the percentage of that in normal rat pancreatic tissue (control group), with the individual ratio of the optical density (OD) of the Cpn60 band versus the OD of the corresponding GAPDH. Compared to that of control group, the expression of Cpn60 protein showed no significant change in the sham group, but demonstrated an initial increase followed by a decrease thereafter in the SAP group. At 1 h, the expression of Cpn60 protein in SAP rats reached to 203.5 ± 22.3% of control group (p < 0.01), but the difference decreased as the SAP induction time progressed. At 5 h and 10 h of SAP induction, the expression of Cpn60 protein was no different from that of the control group. Compared to corresponding time points in the sham group, the expression of Cpn60 protein at 1 h, 5 h, 10 h SAP induction accounted for 203.5 ± 22.3% (vs. 83.8 ± 15.4% in the sham group; p < 0.05), 114.4 ± 11.3% (vs. 92.6 ± 17.6% in the sham group; p > 0.05), and 94.9 ± 16.3% (vs. 91.8 ± 16.4% in the sham group; p > 0.05), respectively. The expression of Cpn60 protein in different time points in the sham group showed no significant difference.

Fig. 4.

Expression of Cpn60 protein in rat pancreatic tissue by western blot (mean±SD, n = 6). a Western blot profiling of Cpn60 protein expression in rat pancreatic tissue. b Densitometric quantification of Cpn60 protein in rat pancreatic tissue, expressed as the percentage of normal control with the individual ratio of the optical density (OD) of the protein band versus the OD of corresponding GAPDH. *p < 0.01 compared with normal control group and sham group at different time points; #p < 0.05 compared with SAP group at 5 h and 10 h time point

Just as in the change of Cpn60 mRNA expression, so too did the Cpn60 protein expression in the pancreatic tissues of SAP rats decrease as time passed. The decline of Cpn60 expression in the SAP group was sharper: there was a three-fold decrease in Cpn60 expression in the mRNA level, and a 2.2-fold decrease in protein level from 1 to 10-h time points (Figs. 3 and 4b).

The change of Cpn60 protein expression in pancreatic tissues by in situ immunohistochemical detection was shown by the fact that in the field with low magnification, the positive staining was obscure in specimens of normal rat pancreatic tissue, but evident (brown) at all time points in samples of rats from the SAP group (Fig. 5a). Under a high magnification microscope (Fig. 5b), it was found that in normal regions from both the normal tissues and the SAP tissues in which some parts were not yet involved, the pancreatic acinar cells showed structural integrity, lined up neatly with normal nuclear morphology, and brown granules were observed only in the cytoplasm of a small number of cells (region I in Fig. 5b). In the area where the pancreatic acini were damaged, acinar cells shrank, and the cell nuclei showed different changes with chromatin margination, pyknosis, fragmentation, etc., the positive staining was mostly seen and a large number of brown granules concentrated in the cytoplasm (region II in Fig. 5b). In zone III, of Fig. 5b, pancreatic acinar cells completely dissolved, hence, the decline in positive staining.

Fig. 5.

Expression of Cpn60 protein in rat pancreatic tissue by immunohistochemical staining (SP) in situ. a 100× magnification: normal pancreatic tissue displays no obvious positive staining while tissues in rats of the SAP group show obvious positive staining (brown granules). b 400× magnification: in area I, pancreatic acinar remains structurally intact with very few brown granules. Area II has strong positive staining with intracytoplasmic large brown granules and damaged pancreatic acinar structures, and abnormity of the cell nuclei including chromatin margination, pyknosis, fragmentation, or absence, indicating that necrosis occurred in these acinar cells. Area III shows complete necrosis and diminished positive staining

The immunohistochemically positive signals were measured semi-quantitatively and the average optical density (OD) represented the positive staining intensity. The results showed that Cpn60 protein expression was increased in the SAP group at different time points, compared with that in normal group (p < 0.01; Table 1).

Table 1.

Expression of Cpn60 protein in rat pancreatic tissues—semi-quantitative analysis (±SD)

| Group | N (slides read) | OD |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | 10 | 0.0102 ± 0.0023 |

| SAP1h | 11 | 0.1985 ± 0.0061*, ** |

| SAP5h | 15 | 0.2267 ± 0.0096* |

| SAP10h | 15 | 0.2172 ± 0.0085* |

Expression of Cpn60 protein in pancreatic tissues of SAP rats by immunohistochemical staining (SP) in situ. Image analysis was accomplished by semi-quantification using digital Motic Med 6.0 image analysis system (Motic, Germany). Results are expressed as mean ± SD for three independent experiments using three rats at least. The average optical density (OD) represents the positive staining intensity.

*p < 0.01, compared with the normal control group

**p < 0.05, compared with the subgroup of SAP 5 h or SAP 10 h

Discussion

Experimental studies reveal that there are changes in levels of HSPs in acute pancreatitis (AP) because of bodily and pancreatic stress (Takacs et al. 2002; Hennequin et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2000). It was found that caerulein heightens the mRNA expression of HSPs, and lessens the HSPs protein expression in rats with AP (Strowski et al. 1997). By contrast, different results have also been reported (Ethridge et al. 2000; Rakonczay et al. 2002b; Tashiro et al. 2002; Li et al. 2003). This lack of agreement may be caused by the use of different AP models resulting in a variety of lesions, e.g., sodium taurocholate (TC) and arginine often induce acute necrotizing pancreatitis, while caerulein causes edema pancreatitis. The different time points of observation and sampling may be also responsible for the inconsistent results because of the dynamic changes of HSPs in the process of AP. In this study, the authors employed the SAP replication rat model and observed the Cpn60 expression in rat pancreatic tissue at different times. The results demonstrate that the expression of Cpn60 in rats with SAP, at the mRNA level, is higher than that in rats of a sham group at 1 h observation time point, and also higher than that in control rats. The expression of Cpn60 subsequently decreases sharply, as the AP course extends, and there is a significant difference in the decline between the SAP 1 h and 10 h subgroup. At the protein level, the expression of Cpn60 in the pancreatic tissues of rats increases at 1 h SAP induction also, and decreases sharply in rats of the SAP group with longer AP induction. In SAP rats with 5 or 10 h SAP induction, the expression of Cpn60 is slightly higher than those of the sham group at the same time points, but shows no significant difference compared to that of the control group. From the results of these experiments, the stress of operation did not generate a substantial change of Cpn60 expression in the pancreatic tissues of rats, as demonstrated in the sham groups, in which the expression of Cpn60 showed no significant change. However, the expression of Cpn60 changes significantly in the SAP group, increases rapidly at both mRNA and protein levels with 1 h AP induction, and decreases with 5 h or 10 h SAP induction. Noticeably, the diminishing Cpn60 expression in rats of the SAP group is obvious.

Most experimental results evinced elevated expression of HSPs in pancreatic tissue during stress, representing the cell adaptive protection response, as elevated HSPs have a protective effect on the pancreatic tissue and delay the onset, to some extent, of experimental AP (Wagner et al. 1996; Seo et al. 2005; Tashiro et al. 2002; Ethridge et al. 2000; Hennequin et al. 2001; Lee et al. 2000; Grise et al. 2000). Lee et al. (2000) have induced high expressions of Cpn60 by using flood stress, and have thus ameliorated the pancreatic edema of caerulein-induced AP, and prevented the activation of trypsin in acinar cells. Rakonczay Jr. has found that hot water immersion significantly increases HSP72 expression in rat pancreas, while cold water immersion significantly enhances Cpn60 expression. However, the high Cpn60 expression in rat pancreatic tissue provoked by pre-immersion in cold water can alleviate the pancreatic edema and increase serum enzymes in rats with TC-induced AP, while the elevated HSP72 expression stimulated by pre-immersion in hot water exhibits no evident effect on these indications (at 6 h after AP replication; Rakonczay et al. 2002a). Combined with our present results and the investigation of Strowski et al, the rapid drop of Cpn60 protein expression in pancreatic tissue during AP is the result of, and possibly a causative factor for, the pathogenesis and development of AP as well (Strowski et al. 1997). The pathological examination of pancreatic tissue in the study confirms that hemorrhage and necrosis were apparent 1 h after AP replication, and the scenario worsens as time passes, suggesting the possible correlation between the drop of Cpn60 protein and the severity of SAP progression. The causality, however, needs to be further investigated.

The immunohistochemical detection in this study showed that Cpn60 protein stains were obscure in normal pancreatic tissue, but unquestionably positive in specimens of SAP rats. It is obvious that the affected necrosing zones in the pancreatic acinar cells of SAP rats are the primary sites that stain positive for Cpn60. When acinar cells are severely damaged and disappear, light staining occurs. An interesting finding is that the expression of Cpn60 has been detected in normal rat pancreatic tissue by RT-PCR and western blotting, but very little by the immunohistochemical method. How should this be interpreted? In their study of the correlation of the membrane protein Ecto-F1-ATPase and MHC-I, Vantourout et al. recently reported that when MHC-I was expressed in sufficient quantity intracellularly, it formed a complex with Ecto-F1-ATPase and blocked antibody binding onto Ecto-F1-ATPase, resulting in negative staining of the protein (Vantourout et al. 2008). Our results may have a similar explanation, i.e., when Cpn60 is functioning as a normal chaperone, does it combine with pancreatic enzymes and shield the antigenic epitopes and, hence, the pseudo-negative staining?

In summary, during AP, the expression of both Cpn60 mRNA and protein showed a transient elevation in the pancreatic tissue of AP rats, predominantly in the affected, but not totally destroyed, pancreatic acinar cells. Thus, as AP progressed, pancreatic tissues were seriously damaged, leading to a decreased Cpn60 expression. The causality between the damage of pancreatic acinar cells and the decrease of Cpn60 level needs to be further investigated.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 30570845 and 30770978 to YY Li).

Footnotes

Xue-Li Li and Kun Li contributed equally to this work.

References

- Bruneau N, Lombardo D, Levy E, Bendayan M. Roles of molecular chaperones in pancreatic secretion and their involvement in intestinal absorption. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;49:329–345. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000515)49:4<329::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cechetto JD, Soltys BJ, Gupta RS. Localization of mitochondrial 60-kD heat shock chaperonin protein (Hsp60) in pituitary growth hormone secretary granules and pancreatic zymogen granules. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:45–56. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deocaris CC, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R. On the brotherhood of the mitochondrial chaperones mortalin and heat shock protein 60. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2006;11:116–128. doi: 10.1379/CSC-144R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethridge RT, Ehlers RA, Hellmich MR, Rajaraman S, Evers BM. Acute pancreatitis results in induction of heat shock proteins 70 and 72 and heat shock factor-1. Pancreas. 2000;21:248–256. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grise K, Kim F, McFadden D. Hyperthermia induces heat-shock expression, reduces pancreatic injury, and improves survival in necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2000;21:120–125. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennequin C, Collignon A, Karjalainen T. Analysis of expression of GroEL (Hsp60) of Clostridium difficile in response to stress. Microb Pathog. 2001;31:255–260. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwich AL, Fenton WA, Rapoport TA. Protein folding taking shape. Workshop on molecular chaperones. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:1068–1073. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskin O, Bahar I, Flatow D, Covell DG, Jernigan RL. Molecular mechanisms of chaperonin GroEL-GroES function. Biochemistry. 2002;41:491–495. doi: 10.1021/bi011393x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger B, Weber IA, Albrecht E, Mooren FC, Lerch MM. Effect of hyperthermia on premature intracellular trypsinogen activation in the exocrine pancreas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:159–165. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Bhagat L, Frossard JL, Hietaranta A, Singh VP, Steer ML, Saluja AK. Water immersion stress induces heat shock protein 60 expression and protects against pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:220–229. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Rimler G, Bell RE, Ben-Tal N, Azem A. Type I chaperonins: not all are created equal. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YY, Bendayan M. Alteration of chaperonin60 and pancreatic enzyme in pancreatic acinar cell under pathological condition. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7359–7363. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i46.7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YY, Gingras D, Londono I, Bendayan M. Expression differences in mitochondrial and secretory chaperonin 60 (Cpn60) in pancreatic acinar cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:287–294. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0287:EDIMAS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Li YY. The construction and function of Cpn60 and involvement in clinic. Journal of Tongji University, Medical Science. 2007;28:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rakonczay Z, Jr, Takacs T, Ivanyi B, et al. The effects of hypo- and hyperthermic pretreatment on sodium taurocholate-induced acute pancreatitis in rats. Pancreas. 2002;24:83–89. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakonczay Z, Jr, Takacs T, Ivanyi B, et al. Induction of heat shock proteins fails to produce protection against trypsin-induced acute pancreatitis in rats. Clin Exp Med. 2002;2:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s102380200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer C, Williams JA. Stress kinases and heat shock proteins in the pancreas: possible roles in normal function and disease. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1–9. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J, Rattner DW, Lewandrowski K, Compton CC, Mandavilli U, Knoefel WT, Warshaw AL. A better model of acute pancreatitis for evaluating therapy. Ann Surg. 1992;215:44–56. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SW, Koo HN, An HJ, et al. Taraxacum officinale protects against cholecystokinin-induced acute pancreatitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:597–599. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltys BJ, Gupta RS. Mitochondrial proteins at unexpected cellular locations: export of proteins from mitochondria from an evolutionary perspective. Int Rev Cytol. 2000;194:133–196. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strowski MZ, Sparmann G, Weber H, et al. Caerulein pancreatitis increases mRNA but reduces protein levels of rat pancreatic heat shock proteins. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G937–G945. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs T, Rakonczay Z, Jr, Varga IS, Ivanyi B, Mandi Y, Boros I, Lonovics J. Comparative effects of water immersion pretreatment on three different acute pancreatitis models in rats. Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;80:241–251. doi: 10.1139/o02-006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro M, Ernst SA, Edwards J, Williams JA. Hyperthermia induces multiple pancreatic heat shock proteins and protects against subsequent arginine-induced acute pancreatitis in rats. Digestion. 2002;65:118–126. doi: 10.1159/000057713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vantourout P, Martinez LO, Fabre A, Collet X, Champagne E. Ecto-F1-ATPase and MHC-class I close association on cell membranes. Molecular Immunology. 2008;45:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AC, Weber H, Jonas L, et al. Hyperthermia induces heat shock protein expression and protection against cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1333–1342. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]