Abstract

Objective

It is important to find ways to predict response to treatments as this may inform treatment planning. We examined rapid response in obese patients with BED who participated in a randomized placebo-controlled study of orlistat administered with cognitive behavioral therapy delivered by guided self-help (CBTgsh) format.

Methods

Fifty patients were randomly assigned to 12-week treatments of either orlistat+CBTgsh or placebo+CBTgsh, and were followed in double-blind fashion for three months after treatment discontinuation. Rapid response, defined as 70% or greater reduction in binge-eating by the fourth treatment week, was determined by receiver operating characteristic curves, and was then used to predict outcomes.

Results

Rapid response characterized 42% of participants, was unrelated to participants’ demographic features and most baseline characteristics, and was unrelated to attrition from treatment. Participants with rapid response were more likely to achieve binge eating remission and 5% weight loss. If rapid response occurred, the level of improvement was sustained during the remaining course of treatment and the 3-month period after treatment. Participants without rapid response showed a subsequent pattern of continued improvement.

Conclusion

Rapid response demonstrated the same prognostic significance and time course for CBTgsh as previously documented for individual CBT. Among rapid responders, improvements were well-sustained, and among non-rapid responders, continuing with CBTgsh (regardless of medication) led to subsequent improvements.

Keywords: rapid response, binge eating disorder, obesity, cognitive behavior therapy, orlistat, guided self-help

1. Introduction

Binge eating disorder (BED), a research category in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 1994), is characterized by recurrent binge eating without inappropriate weight control behaviors. BED is a prevalent (Hudson et al., 2007), stable problem (Pope et al., 2006) associated with heightened medical (Johnson, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) and psychological problems (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001a; White & Grilo, 2006). Not only do obese persons with BED have significantly greater eating and psychological disturbances than obese persons without BED (Allison, Grilo, Masheb, & Stunkard, 2005), new evidence suggests that BED represents a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals (Hudson et al., 2006). Although effective treatments have been identified for BED (National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2004; Wilson, Grilo, & Vitousek, 2007), even in studies with the best outcomes, a substantial proportion (a third to a half) of patients do not achieve abstinence from binge eating and most clinical trials have reported little to no weight loss (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005; Wilfley et al., 2002). Thus, it is important to find ways to predict response to treatments as this may both inform treatment planning and lead to more effective decision-making about treatment prescriptions for patients with BED.

Finding reliable patient predictors of treatment outcome for BED and other eating disorders has proven to be difficult (Wilson et al., 2007). One promising predictor may be initial treatment response. Studies of bulimia nervosa (BN) have identified rapid response to treatment as a significant predictor of positive treatment outcome (Agras et al., 2000; Fairburn, Agras, Walsh, Wilson, & Stice, 2004; Wilson et al., 1999; Wilson et al., 2002). More broadly, these findings regarding the predictive value of rapid response in treatment for BN echo those of the emerging literature on “sudden gains” as a predictor of outcomes in depression across different interventions, including psychological (Hardy et al., 2005; Tang & DeRubeis, 1999; Tang, Luborsky, & Andrusyna, 2002) and antidepressant (Taylor et al., 2006) treatments.

In the first such study with BED, Grilo and colleagues (2006) found that patients characterized by rapid response (defined as 65% or greater reduction in binge eating by the fourth week of treatment) were more likely to achieve binge eating remission, had greater improvements in eating disorder psychopathology, and had greater weight loss than patients without rapid response. Grilo and colleagues (2006) also found that rapid response had different prognostic significance and distinct time courses for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and medication treatments. If rapid response occurred in CBT, the level of improvement was sustained or improved further during the remaining course of treatment, whereas if it occurred with medication, there was a trend for some of the improvement to be subsequently lost. Importantly, among non-rapid responders to treatment, those receiving CBT showed a subsequent pattern of continued improvement whereas those receiving medication were unlikely to derive any further benefit from continuing that medication. These findings for BED (grilo et al., 2006) have some interesting parallels in the “sudden gains” literature for depression. Tang and colleagues (2002) reported that sudden gains in CBT for depression were significantly more robust than those for an alternative psychological therapy. Collectively, these findings highlight the need for research on rapid response across different treatment methods.

CBT is currently considered the best established treatment for BED (NICE 2004; Wilson et al., 2007). CBT, however, requires specialized training and resources and is not readily available in many clinical settings (Crow et al., 2004). Recent research has supported the clinical utility of CBT delivered using guided self-help methods (e.g., Carter & Fairburn, 1998; Grilo & Masheb, 2005). Such promising findings have led to treatment guidelines (NICE 2004) suggesting that while CBT is currently considered the best established treatment for BED (NICE 2004; Wilson et al., 2007), CBT delivered in a self-help format may in fact be the most practical first-line treatment for the disorder.

Research on rapid response in “first-line” treatments such as guided self-help CBT is important for various reasons. First, it is important to ascertain whether the robust rapid response findings observed for CBT delivered more intensively via individual sessions are observed for CBTgsh delivered with less clinician/therapeutic contact. One study with depression, for example, found that sudden gains in response to CBT delivered in busy routine clinical settings were less stable and robust than those reported in clinical trials using intensive standardized CBT (Hardy et al., 2005). Second, it is important to determine whether the lack of an early rapid response to guided self-help CBT should signal immediate consideration of alternative treatments. For example, two studies of antidepressant medications have found that patients with BED (Grilo et al., 2006) and with BN (Walsh, Sysko, & Parides, 2006) who fail to show a rapid response are very unlikely to show a subsequent response and should therefore be switched to another treatment, whereas patients receiving individual CBT who do not have a rapid response should not be switched because they are quite likely to show a subsequent improvement (Grilo et al., 2006). Third, it is important to determine whether rapid response to CBTgsh, if it occurs, is durable and this has yet to be studied with any treatment for BED. Studies of sudden gains in CBT for depression have produced mixed findings, with one report indicating good durability (Tang et al., 2002) and one report suggesting poor prognosis (Vittengl et al., 2005).

Thus, in the present study, we examined rapid response in obese patients with BED who participated in a randomized placebo-controlled study testing the effectiveness of orlistat administered with CBT delivered by guided self-help (CBTgsh) (Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005). We aimed to: (a) examine whether rapid response previously documented for CBT (Grilo et al., 2006) also occurs in CBTgsh; (b) determine whether rapid response prospectively predicts treatment outcomes; (c) examine the course of patients with rapid response to determine whether the improvements are well-sustained during treatment and persist after treatment; and (d) examine the course of patients without rapid response to determine whether the lack of an early response to CBTgsh should signal consideration of alternative treatments.

2. Methods

Subjects

Participants were 50 consecutively evaluated adult patients who met DSM-IV research criteria for BED and participated in a randomized placebo-controlled study of orlistat administered with guided-self-help CBT (CBTgsh). A detailed description of the aims, design, methods, and outcomes of this study has been reported elsewhere (Grilo, Masheb, & Salant, 2005) but is briefly described here. Inclusion criteria included: 35–60 years of age, body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater, and DSM-IV research criteria for BED. Exclusionary criteria included: concurrent treatment for eating, weight, or psychiatric illness; medical conditions (diabetes or thyroid problems) that influence weight or eating; severe current psychiatric conditions requiring different treatments (psychosis, bipolar disorder); and pregnancy or lactation. The study received full human subjects review and approval by the Human Investigation Committee and IRB at the Yale University School of Medicine.

Fifty individuals who met eligibility requirements and completed baseline assessment procedures were randomized to one of two treatment conditions (orlistat+CBTgsh or placebo+CBTgsh as described below) based on the order in which they were accepted into the study. The 50 participants were aged 35 to 58 years (mean=47.0, SD=7.0), 88% (N=44) were female, and 82% (N=41) attended or finished college. The group was 88% (N = 44) Caucasian, 6% (N=3) African American, and 6% (N=3) Hispanic American. Mean body mass index (BMI; weight (kg) divided height (m2)) was 36.0 (SD=4.7).

Diagnostic Assessment and Outcome Measures

Diagnostic and assessment procedures were performed by trained and monitored doctoral-level research-clinicians. DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorder diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; First et al., 1996). Inter-rater reliability for BED (kappa = 1.0) and axis I diagnoses (kappa 0.60 to 1.0) was good.

The Eating Disorder Examination Interview - 12th Edition (EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) was administered at baseline to assess the specific features of eating disorders in addition to confirming the BED diagnosis derived on the SCID-I/P. The EDE was re-administered at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up assessments, and was the primary method for determining outcome of binge eating and eating disorder psychopathology. Patients and researchers were blind to medication assignment during the 12-week treatment and throughout the 3-month follow-up period.

The EDE, an investigator-based interview, is the best-established method for assessing eating disorder psychopathology (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001b; Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2001c) and has established reliability with BED (Grilo et al., 2004). Except for diagnostic items, the EDE focuses on the previous 28 days. The EDE assesses the frequency of different forms of overeating, including objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; i.e., binge eating defined as unusually large quantities of food with a subjective sense of loss of control). The EDE is also comprised of four subscales (dietary restraint, eating concern, weight concern, and shape concern) and a global total score. Items are rated on 7-point forced-choice scales (0–6); higher scores reflect greater severity or frequency. Inter-rater reliability for the EDE was assessed using approximately 20% (N=32) of interviews conducted at baseline, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up. Kappa coefficient for diagnosis of BED was 1.0. Intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient for OBE episodes was .97 and ranged from .86 to .97 for the four EDE subscales.

Self-monitoring

Overeating behaviors, including OBEs, were assessed prospectively throughout the course of treatment by self-monitoring using daily record sheets (Grilo et al., 2001b, 2001c; Wilson & Vitousek, 1999). Each daily record inquired whether participants had any OBEs and, if so, how many episodes. The daily record contained the definition of OBEs (using the EDE definition) that was reviewed with participants at the start of treatment. Participants were provided with stapled packets of seven blank daily record sheets for each week. Research clinicians met briefly with participants every other week to collect the self-monitoring records and to check them for accuracy and completeness. Participants were reminded each time of the importance of doing the self-monitoring on a daily basis.

Randomization to Treatment Conditions

Subjects were randomly assigned (without any restriction) by a computer-generated table to one of two12-week treatment conditions: orlistat+CBTgsh (N=25) or placebo+CBTgsh (N=25). Treatment assignment was done after the completion of all assessments and was performed independently from the investigators by a research pharmacist at a separate Yale facility. To ensure concealment of the randomization, medication (orlistat and placebo) was prepared in identical appearing capsules.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – Guided Self-Help (CBTgsh)

The CBT was administered individually using a guided self-help (CBTgsh) approach following the guidelines of previous trials with BED (Carter & Fairburn, 1998; Grilo & Masheb, 2005). Participants were provided with a copy of Overcoming Binge Eating (Fairburn, 1995), which is the self-help CBT patient manual step-by-step version of the therapist manual (Fairburn et al., 1993) used in previous trials (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005). The self-help program consists of six steps that address how to assess and change eating behaviors (including binge eating) and other associated features. The six steps are additive and designed to be followed sequentially, such that some progress on one step is required prior to moving on.

The guided self-help protocol included six brief individual meetings (15–20 minute sessions) during the 12-week period by doctoral research-clinicians. The research clinicians focused primarily on (a) maintaining and enhancing motivation; (b) correcting any misunderstanding of the information; (c) addressing difficulties with relevant skill-building exercises in the manuals; and (d) reinforcing the necessity for self-monitoring and record keeping. Research clinicians received intensive training and weekly supervision throughout the course of treatments from the investigators.

Pharmacological Treatment With Orlistat

Orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, is a non-centrally acting medication that produces a dose-dependent reduction in dietary fat absorption, with a maximum 30% reduction accomplished with dosing of 120 mg three times per day (Drent & van der Veen, 1993). This dosing has consistently demonstrated efficacy for weight loss in obese patients (O’Meara et al., 2004).

Pharmacological treatments were administered in double-blind placebo-controlled fashion. Participants received either orlistat (120 mg 3 times a day) or pill placebo (3 times a day) during the 12-week treatment. The blinded medication regimen was fixed-dose throughout the study. The pharmacological treatment consisted of basic clinical management procedures modified for the use of Orlistat (Davidson et al., 1999). Participants were instructed to take the medication three times each day with breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals. Patients were given a once-daily multivitamin containing fat-soluble vitamins and were instructed to take it two hours prior to the study medication at dinner.

The clinical management involved brief individual meetings (less than 15 minutes and averaging 10 minutes) held weekly during the first four weeks and monthly thereafter. Meetings focused on the medication regimen, including: nature of the medication and rationale for its use; adherence and compliance with the dosing (direct interview and pill counts); problem-solving issues of non-compliance, if needed; assessment of side effects; and – if present – methods for coping with side effects. Participants were instructed to adhere to the following guidelines: (a) eat three meals and 2–3 snacks per day; (b) aim for modest balanced calorie diet with goals of 1200 kcal/day for women and 1500 kcal/day for men; (c) limit fat to less than 30% of intake; and (d) follow USDA Food Guide Pyramid to aid in balanced food choices and portion sizes.

Three-Month Follow-up Period

The double-blind of the medication condition was broken after completion of all assessments at the end of the 3-month follow-up visit. No treatment (either CBTgsh or orlistat) was provided during the 3-month follow-up period after completing the 12-week treatments. During this period of time, it is possible (and clinically desirable) that participants utilized the principles or techniques of the CBT they learned during the course of CBTgsh. Participants were encouraged not to seek orlistat prescriptions or begin treatments before the 3-month follow-up without notifying the investigators for assistance with treatment-planning or referrals. During the follow-up assessments, questioning revealed no cases in which orlistat had been obtained or other treatments had been initiated. There were a few cases of non-completers for whom such follow-up data could not be obtained. Our primary analytic method (intent-to-treat analyses using the baseline-carried-forward-method) minimizes the likelihood of confounds in those few cases impacting the results.

Statistical Analyses

Defining Rapid Response

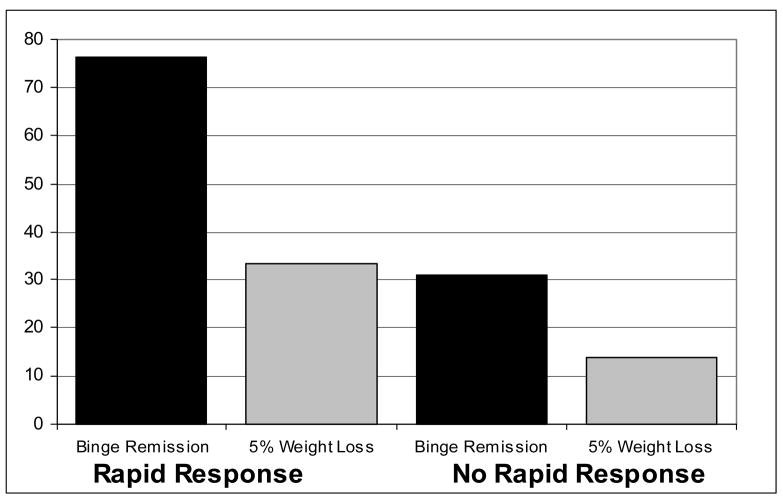

The definition of rapid response was informed by previous studies on rapid response using variants of signal detection methods in patients with BED and BN. Following the study by Grilo and colleagues (2006), we constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using the percentage of reduction in binge eating during the first four weeks to predict the primary post-treatment outcome of remission from binge eating. The percentage reduction in binge eating from baseline at each week (determined using daily self-monitoring) was calculated along with the total percentage reduction from baseline observed during the first four weeks (i.e., month 1, given the possibility of weekly fluctuations in binge eating). The ROC curves, a form of signal detection, serve as a hypothesis-generating working definition of rapid response. ROC curves allow testing the accuracy of the different measures (percentage reductions in binge eating based on self-monitoring during the early stages of treatment) for correctly predicting the post-treatment outcome of binge eating remission (based on the Eating Disorder Examination). These ROC curves are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves Predicting Binge Remission.

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves predicting binge remission post-treatment based on percentage reduction in binge eating observed at weeks 1 to 4 and for total of weeks 1 through 4 (month 1). ROC curve for month 1 is most predictive and is in bold.

The ROC curve for month 1 emerged as most predictive overall based on overall area under the curve (AUC) and also specifically on the portion of the curves of most interest (i.e., lower false positive rates)(Streiner & Cairney, 2007). The area under this curve equaled .78 (SE=.07), with the 95% confidence interval [CI] = .65 –.90; p<.001 for the null hypothesis that true area =0.5. AUC between .70 and .90 are generally viewed to reflect moderate accuracy (Streiner & Cairney, 2007). Inspection of this ROC revealed that a reduction of 70% or greater in binge eating by the fourth week maximized sensitivity and 1-specificity (.64 and .20, respectively) (McFall & Treat, 1999). These results are consistent with the findings reported by Grilo and colleagues (2006) previously for BED.

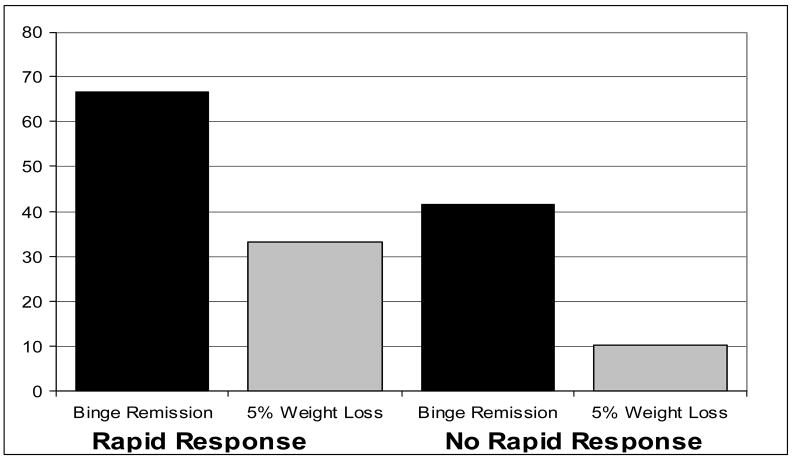

We constructed a second set of ROC curves in which the percentage reduction in binge eating from baseline at each week and for the first month were used to predict the occurrence of both binge eating remission and 5% weight loss at post-treatment. These ROC curves are shown in Figure 2. The ROC curve for month 1 emerged as most predictive overall (area under this curve equaled .78 (SE=.08), with the 95% confidence interval [CI] = .62 –.94; p<.009 for the null hypothesis that true area =0.5. Inspection of this ROC revealed that a 70% or greater reduction in binge eating maximized sensitivity and 1-specificity (.78 and .34, respectively).

Figure 2. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves Predicting Both Binge Remission and 5% Weight Loss.

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves predicting cases in which both binge remission and 5% weight loss occurred at post-treatment based on percentage reduction in binge eating observed at weeks 1 to 4 and for total of weeks 1 through 4 (month 1). ROC curve for month 1 is most predictive and is in bold.

Comparison of Participants with and without Rapid Response

Participants classified as rapid responders were compared to those without a rapid response on demographic variables, psychiatric co-morbidity, and clinical variables at baseline. Rapid response was then used to predict outcomes at post-treatment and at 3-month follow-up after discontinuation of treatment.

Treatment Outcomes

Analyses compared rapid responders and non-rapid responders on attrition and on the primary outcomes at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up using Intent-To-Treat (ITT)) analyses in which missing data were replaced by baseline values (i.e., baseline-carried-forward analysis). Primary treatment outcomes were: (a) “remission” from binge eating, which was defined as zero binges for the past month based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview assessment of OBEs; and (b) weight loss considered categorically as achieving a 5% weight loss from baseline weight. A weight loss of 5% is associated with improvements in most obesity-related medical consequences (Goldstein 1992), accurately predicts sustained improvements in weight and obesity-related factors (Rissanen et al., 2003), and has become a standard outcome (e.g., Davidson et al 1999).

3. Results

Rapid Response and Patient Characteristics

Of the 50 patients randomized to treatment, 21 (42%) showed a rapid response, defined in this study as 70% or greater reduction in binge eating by the fourth treatment week. Rapid responders did not differ significantly from participants not showing rapid response on demographic features (age, gender, ethnicity, education) or age of onset of BED as summarized in Table 1. Table 1 also shows that rapid responders did not differ from non-rapid responders in the overall frequency of axis I psychiatric disorders, mood disorders, or substance use disorders, although rapid responders did have a higher rate of anxiety disorders. As shown in Table 2, rapid responders did not differ significantly from participants not showing a rapid response on pretreatment levels of binge eating, eating disorder features (EDE subscales or global severity) or BMI.

Table 1.

Demographic and Psychiatric Characteristics of Participants With and Without a Rapid Response

| Rapid Response | No Rapid Response | Test Statistic | P value | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 21) | (N = 29) | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.0 (7.5) | 46.2 (7.1) | 0.01 | .92 ns | .00 |

| Female, No (%) | 18 (85.7) | 26 (89.7) | 0.18 | .67 ns | .06 |

| Ethnicity, No (%) | 2.48 | .29 ns | .19 | ||

| Caucasian | 20 (95.2) | 24 (82.8) | |||

| African-American | 1 (4.8) | 2 (6.9) | |||

| Hispanic-American | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.3) | |||

| Education, No (%) | 0.42 | .81 ns | .09 | ||

| College | 12 (57.1) | 15 (51.7) | |||

| Some college | 6 (28.6) | 8 (27.6) | |||

| High School | 3 (14.3) | 6 (20.7) | |||

| DSM-IV Dx, lifetime, No (%) | |||||

| Any Axis I psychiatric disorder | 12 (57.1) | 18 (62.1) | 0.12 | .73 ns | .05 |

| Mood disorders | 8 (38.1) | 17 (58.6) | 2.05 | .15 ns | .20 |

| Anxiety disorders | 9 (42.9) | 3 (10.3) | 7.06 | .008 | .38 |

| Substance use disorders | 2 (9.5) | 3 (10.3) | 0.01 | .92 ns | .01 |

| Age onset BED, mean (SD) | 26.2 (12.9) | 24.8 (13.4) | 0.14 | .71 ns | .00 |

Note: Test statistic = chi-square for categorical variables and ANOVAs for dimensional variables. P values are for two-tailed tests. SD = standard deviation. No = number. BED = binge eating disorder. Effect size measures are phi coefficients for categorical variables and partial eta-squared for dimensional variables.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics at Baseline of Participants With and Without a Rapid Response

| Rapid Response | No Rapid Response | F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 21) | (N = 29) | |||

| Binge Eating (OBEs), mean (SD) | ||||

| Binge days/month (EDE) | 13.7 (5.8) | 14.2 (6.5) | 0.08 | .78 ns |

| Binge episodes/month (EDE) | 13.9 (5.7) | 15.6 (8.5) | 0.68 | .41 ns |

| Eating disorder psychopathology, mean (SD) | ||||

| Dietary restraint (EDE) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.51 | .48 ns |

| Eating concern (EDE) | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.07 | .79 ns |

| Weight concern (EDE) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.8) | 0.05 | .83 ns |

| Shape concern (EDE) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.8) | 0.56 | .46 ns |

| Global Score (EDE) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) | 0.29 | .59 ns |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 35.6 (4.8) | 37.1 (4.8) | 1.11 | .30 ns |

Note: F is value for ANOVA. P values are for two-tailed tests. SD = standard deviation. EDE = Eating Disorder Examination interview. OBE = objective bulimic episodes.

Rapid Response and Primary Treatment Outcomes (Binge Remission and 5% Weight Loss)

Of the 50 randomized patients, 78% (N=39) completed treatments without differential drop-out between orlistat or placebo (χ2 (df = 1; N = 50) = 0.117, p = .733 ns). Rapid responders did not differ significantly from participants not showing rapid response on attrition from treatment (χ2 (df = 1; N = 50) = 1.256, p = .262 ns; phi coefficient (effect size measure for contingency table analyses) = .16).

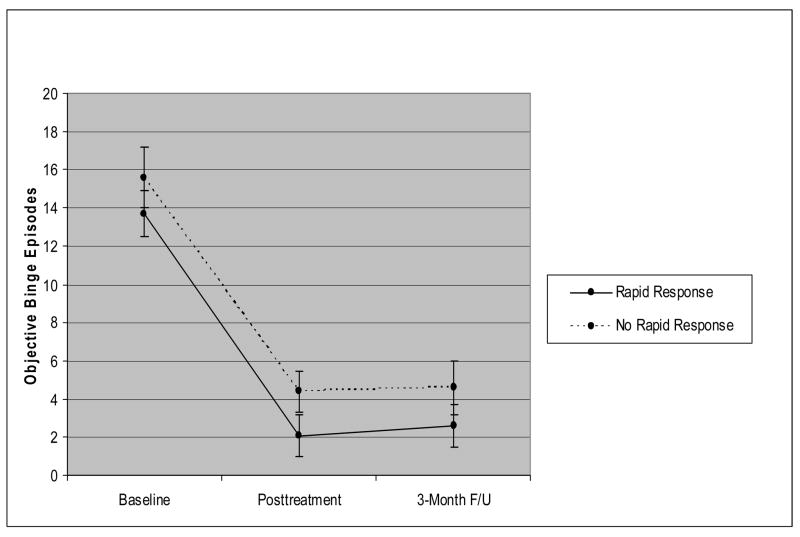

Figure 3 summarizes the proportion of participants with versus without a rapid response who achieved the two primary outcomes (remission from binge eating and 5% weight loss) at post-treatment. Participants with a rapid response were significantly more likely than those without a rapid response to achieve remission from binge eating (76.2% (n = 16 of 21) versus 31.0% (n = 9 of 29); χ2 (df = 1; N = 50) = 9.93, p = .002; phi coefficient = .45). Thirty-three percent (7 of 21) of participants with a rapid response versus 13.8% (4 of 29) of participants without a rapid response achieved at least 5% weight loss (χ2 (df = 1; N = 50) = 2.71, p = .10; phi coefficient = .23). When weight loss was considered dimensionally, participants with a rapid response had a statistically non-significant trend to have lost a greater percentage of weight than participants without rapid response (M=3.2 (SD=3.4) vs. M=1.8 (SD=2.5); F=2.95, p=.09; partial eta squared = .06). This translates to a rather modest difference; i.e., a mean of 3.3 kg vs 2.0 kg.

Figure 3. Rapid Response and Outcomes at Post-Treatment (N=50).

Percentage of patients achieving remission from binge eating and 5% weight loss from baseline to post-treatment shown separately for patients with rapid response versus without rapid response. Data are for all randomized patients (N=50) in intent-to-treat analyses (baseline carried forward method for non-completers). Rapid response is defined as 70% or greater reduction in frequency of binge eating episodes by the fourth treatment week based on daily prospective self-monitoring. Binge remission is defined as zero binge episodes for the past month based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview.

Figure 4 summarizes the findings between rapid response status and primary outcomes at follow-up three months after completing treatments. Sixty-seven percent (14 of 21) of patients with a rapid response versus 41.4% (12 of 29) of patients without a rapid response were binge remitters at 3-month follow-up (χ2 (df = 1; N = 50) = 3.12, p = .077; phi coefficient = .25). Patients with a rapid response were significantly more likely than those without a rapid response to have sustained a 5% weight loss three months after treatment (33.3% (n = 7 of 21) versus 10.3% (n = 3 of 29); χ2 (df = 1; N = 50) = 4.02, p = .045; phi coefficient = .28).

Figure 4. Rapid Response and Outcomes at 3-Month Follow-Up (N=50).

Percentage of patients achieving remission from binge eating and 5% weight loss from baseline to three-month follow-up shown separately for patients with rapid response versus without rapid response. Data are for all randomized patients (N=50) in intent-to-treat analyses (baseline carried forward method for non-completers). Rapid response is defined as 70% or greater reduction in frequency of binge eating episodes by the fourth treatment week based on daily prospective self-monitoring. Binge remission is defined as zero binge episodes for the past month based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview.

Time Course of Rapid Response

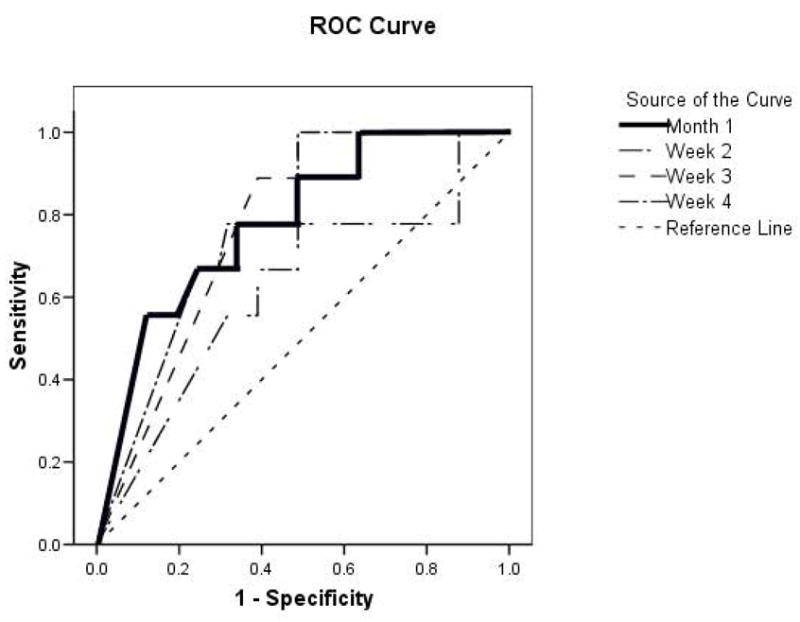

In terms of time course, Figure 5 shows the monthly frequency of binge eating by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response during the 12-week course of treatment. These data, which are based on daily prospective self-monitoring, are shown for treatment completers (n=39). At post-treatment when binge eating was considered dimensionally, patients with rapid response had significantly fewer OBEs than non-rapid responders (M=1.1 (SD=4.6) vs. M=4.5 (SD=5.4); F=5.99, p<.02, partial eta squared = .14). As is evident in Figure 5, the improvements in binge eating by the rapid responders are well-maintained throughout the remaining course of treatment. Among the patients without rapid response, a subsequent pattern of continued improvement is observed during the remaining course of treatment.

Figure 5.

Monthly frequency of binge eating by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response during the 12-week course of treatment. The data are based on daily prospective self-monitoring and are shown for treatment completers (n=39).

Figure 6 shows the monthly frequency of binge eating by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response at post-treatment and again at the follow-up assessment conducted three months after completing treatments. These data are based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview and are shown for all N=50 participants (ITT with baseline carried forward). As is evident in Figure 6, not only is rapid response well-maintained throughout the remaining course of treatment (consistent with the self-monitoring findings noted above) it is well-sustained at the 3-month follow-up. Importantly, among the patients without rapid response, the subsequent pattern of continued improvement observed during the remaining course of treatment is well sustained following the completion of treatment. Indeed, by 3-month follow-up, patients with versus without rapid response did not differ significantly in the mean frequency of OBEs (M=2.6 (SD=4.9) vs. M=4.6 (SD=7.4); F=1.09, p=.30).

Figure 6.

Monthly frequency of binge eating by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response at baseline, post-treatment, and again at the follow-up assessment conducted three months after completing treatments. The data are based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview and are shown for all N=50 participants (ITT with baseline carried forward).

Exploratory Analyses: Rapid Response, Medication Condition, and Primary Treatment Outcomes

Rapid response rates did not differ significantly in patients receiving CBTgsh+orlistat versus CBTgsh+placebo (N = 13 of 25 (52%) versus 8 of 25 (32%); C (df = 1; N = 50) = 2.05, p = .15 ns). Given the (non-significant) trend towards higher rapid response in CBTgsh+orlistat, we performed a series of logistic regression analyses to test the utility of rapid response and medication treatment condition (i.e., orlistat versus placebo conditions combined with CBTgsh). These analyses were purely exploratory in nature given the limited sample sizes.

In terms of achieving remission from binge eating, considered jointly, rapid response and medication condition significantly predicted remission at post-treatment (omnibus χ2 statistic (df = 2, N = 50) = 12.65, p < .002); rapid response (Wald statistic (df = 1) = 7.81, p < .005; Exp(B) = 0.155, 95% C.I. = 0.042 – 0.573) -- but not medication condition (Wald statistic (df = 1) = 2.27, p = .13; Exp (B) = 0.377, 95% C.I. = 0.106 – 1.341) -- made an independent significant contribution. At 3-month follow-up, rapid response showed a non-significant statistical trend as an independent predictor of binge remission (Wald statistic (df = 1, N = 50) = 3.157, p = .076; Exp(B) = 0.336, 95% C.I. = 0.101 – 1.119) when considered jointly with medication condition which was unrelated to binge remission (Wald statistic (df = 1, N = 50) = 0.142, p = .142; Exp(B) = 1.255, 95% C.I. = 0.386 – 4.078). In terms of achieving 5% weight loss, similar logistic regression analyses revealed that rapid response status did not make a statistically significant independent contribution when considered jointly with medication status.

4. Discussion

Rapid response demonstrated the same prognostic significance and time course for CBT delivered using guided self-help (CBTgsh) as previously documented for CBT delivered in traditional individual therapy sessions (Grilo et al., 2006). Rapid response was defined in this study as 70% or greater reduction in binge eating by the fourth week of treatment. This definition was informed by findings from ROC curves constructed to examine the relationship between percentage of reduction in binge eating during the first four weeks of treatment and achieving remission from binge eating at posttreatment. A second series of ROC curves predicting both primary outcomes considered jointly (both binge eating remission and 5% weight loss) showed essentially similar findings and supported the rapid response definition of 70% reduction in binge eating by the fourth week of treatment. Rapid response was observed in 42% of patients, was not significantly associated with attrition from treatment, but was significantly associated with primary treatment outcomes (higher rates of binge remission and 5% weight loss). Among rapid responders, improvements were well-sustained, and among non-rapid responders, continuing with CBTgsh (regardless of medication) led to subsequent improvements that were also well-sustained at 3-month follow-up.

These findings suggest the potential importance of rapid response for treatment decision making in BED. NICE (2004) suggests that a course of self-help CBT is an appropriate first step to consider for treating BED, a recommendation that was bolstered by additional recent findings (Grilo & Masheb 2005). In the case of CBTgsh, rapid response signals a high likelihood of eventual success. Importantly, patients who do not have a rapid response to CBTgsh appear to nonetheless show a subsequent pattern of continued improvement in binge eating that is similar to that achieved by the rapid responders. These findings, unlike those previously reported for pharmacotherapy for BED (Grilo et al., 2006) and BN (Walsh et al., 2006), suggest that continuing with CBTgsh a bit longer may prove beneficial. More broadly, even the binge remission rate of 41.4% observed for the non-rapid-responders at 3-months following treatment completion are higher than remission rates reported for all medication studies for BED (Appolinario et al., 2003; Arnold et al., 2002; Hudson et al., 1998; McElroy et al., 2000) except for topiramate (McElroy et al., 2003).

Participants with and without a rapid response did not differ in demographic factors or personal characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, or education), or severity of eating disorder psychopathology at baseline. Participants with and without a rapid response also differed little in psychiatric co-morbidity: overall, no differences were found for overall psychiatric disorders, mood disorders, or substance use disorders, although interestingly rapid responders were significantly more likely to have an anxiety disorder. Thus, as reported previously (Grilo et al., 2006) rapid response is not easily predicted in BED patients based on these characteristics. Three previous studies with depressed patients that attempted to profile patients who were rapid responders also reported that rapid response (i.e., sudden gains) during treatment for depression was generally unrelated to patient characteristics (Hardy et al., 2005; Kelly et al., 2005; Vittengl et al., 2005). While rapid response was unrelated to most patient characteristics, it is important to note that participants in this study had high levels of eating disorder psychopathology and psychiatric co-morbidity. Overall, 60% of the participants had at least one additional lifetime psychiatric disorder, with 42% meeting criteria for major depressive disorder and 24% for at least one anxiety disorder. These rates of psychiatric co-morbidity and levels of psychological distress (e.g., BDI scores) are similar to those in previous studies of psychological treatments for BED (Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005; Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Wilfley et al., 2002). In addition, these rates of psychiatric co-morbidity are comparable to some previous studies of medication treatments for BED (McElroy et al., 2003) but are substantially greater than most medication trials (Appolinario et al., 2003; Hudson et al., 1998). Thus, the findings regarding rapid response cannot be attributed to low severity or exclusion of poor prognosis patients due to psychiatric co-morbidity.

We note strengths and potential limitations of our study for context. Our methods involved complementary assessments with documented strengths (Grilo et al., 2001b). Importantly, since we used one method to determine rapid response and different methods to determine treatment outcome we reduced a potential method artifact or tautology that might occur by using the same measure to assess both initial response and later outcome. Rapid response was characterized using prospective self-monitoring of binge eating and the primary treatment outcomes relied on independent investigator-based EDE to establish binge eating and measured weights to establish 5% weight loss. A related issue concerning self-monitoring is its potential for producing reactivity. Self-monitoring, when used specifically in treatment, is thought to be an essential ingredient in CBT and hypothesized to account for a portion of the rapid effects of CBT for bulimia nervosa (Wilson & Vitousek, 1999). We can not determine from the present study whether some of the observed effects might simply reflect some degree of reactivity to self-monitoring. We emphasize that our outcomes persisted for three months after discontinuation of treatments.

In terms of limitations, we note that our findings pertain to CBTgsh given concurrently with medication (orlistat or placebo) and basic nutritional guidance and thus the findings may not fully generalize to CBTgsh without any additional intervention. Our relatively small study group size precluded meaningful analyses to test further our main predictive findings by medication condition (orlistat versus placebo given in addition to CBTgsh) and may have not allowed us to find smaller effects. We note that our exploratory logistic regression analyses revealed that the prognostic utility of rapid response for predicting remission from binge eating, but not 5% weight loss, was significant when considered jointly with medication condition. We also note that the amount of weight loss achieved in this brief trial was quite modest and finding ways to produce greater weight loss in this patient group remains a pressing need (Wilson et al., 2007).

Our primary aim concerned prediction of outcomes and future larger studies should explore moderators and mediators of outcomes (Wilson et al., 2007). In addition, the CBTgsh was delivered by specialist doctoral-level research-clinicians and it remains uncertain whether similar outcomes would be achieved by generalist clinicians. The Carter and Fairburn (1998) CBTgsh study utilized non-specialist clinicians and observed good outcomes (based on self-report questionnaires) at post-treatment and 6-month follow-ups. The recent findings that CBTgsh administered to women with bulimia nervosa in primary care settings was ineffective (Walsh et al., 2004), however, suggests the need for future research to establish if CBTgsh can be effectively delivered by non-specialists. Our findings are also limited to treatment-seeking obese persons with BED who responded to advertisements for treatment studies at a medical school and thus may not generalize to BED patients who seek treatment at different types of clinics. It is also possible that obese patients with certain co-morbidities excluded from this study may not derive the same degree of benefit. Lastly, our findings pertain to acute treatment outcome and to short-term (i.e., 3-month) follow-up and the longer-term effect of the relatively brief 12-week interventions is unknown. We note that the CBTgsh has been reported to have good maintenance at 6-month follow-up (Carter & Fairburn 1998). Importantly, Rissanen et al (2003) demonstrated that weight loss of 5% or greater at 12-weeks accurately predicts sustained improvements in weight and major risk factors at two years. Our findings also converge with findings that early improvements (defined as start to 5 weeks) in eating behavior and weight predict subsequent weight loss in obese patients receiving very-low-calorie diets along with behavior therapy for obesity (Stotland & Larocque, 2005).

In summary, rapid response demonstrated the same prognostic significance and time course for CBTgsh as previously documented for CBT delivered in traditional individual therapy sessions (Grilo et al., 2006). Among rapid responders, improvements were well-sustained, and among non-rapid responders, continuing with CBTgsh (regardless of medication) led to subsequent improvements. Importantly, the 3-month follow-up period revealed the durability of CBTgsh as well as demonstrated that the prognostic significance and time courses persisted after discontinuation of treatments for both rapid responders and non-rapid responders. Future research should begin to explore the necessary ingredients and mechanisms for such therapeutic gains and compare the prognostic significance of rapid response for other psychological and behavioral treatments for BED.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (0256230T) and the National Institutes of Health (K24 DK070052) awarded to Dr. Grilo.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5. References

- Agras WS, Crow SJ, Halmi KA, Mitchell JE, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. Outcome predictors for the cognitive behavior treatment of bulimia nervosa: data from a multisite study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1302–1308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: a comparative study of disordered eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1107–1115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Appolinario JC, Bacaltchuk J, Sichieri R, Claudino AM, Gody-Matos A, Morgan C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sibutramine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:1109–1116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Welge JA, Bennett AJ, Keck PE. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63:1028–1033. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow S, Peterson CB, Levine AS, Thuras P, Mitchell JE. A survey of binge eating and obesity treatment practices among primary care providers. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:348–353. doi: 10.1002/eat.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MH, Hauptman J, DiGirolamo M, Foreyt JP, Halsted CH, Heber D, et al. Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:235–242. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drent ML, van der Veen EA. Lipase inhibition: a novel concept in the treatment of obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 1993;17:241–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Stice E. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2322–2324. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: a comprehensive treatment manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders - patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. International Journal of Obesity. 1992;6:397–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM. Self-help and guided self-help treatments for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2000;6:18–26. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL. Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2005a;57:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb CM, Wilson GT. Subtyping binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001a;69:1066–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001b;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obesity Research. 2001c;9:418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biological Psychiatry. 2005a;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Rapid response to treatment for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:602–613. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy GE, Cahill J, Stiles WB, Ispan C, Macaskill N, Barkham M. Sudden gains in cognitive therapy for depression: a replication and extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:59–67. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survery Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Berry JM, Pindyck LJ, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:313–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Raymond NC, Crow SJ, Keck PE, Jr, Carter WP, et al. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: multicenter placebo-controlled double-blind trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1756–1762. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Health problems, impairment and illness associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1455–1466. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MAR, Roberts JE, Ciesla JA. Sudden gains in cognitive behavioral treatment for depression: when do they occur and do they matter? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, Keck PE, Rosenthal NR, Karim MR, et al. Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:255–261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, Lake KA, Soutullo CA, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1004–1006. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall RM, Treat TA. Quantifying the information value of clinical assessments with signal detection theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:215–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) NICE Clinical Guideline No. 9. London: NICE; 2004. Eating Disorders – Core Interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, related eating disorders. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara S, Riemsma R, Shirran L, Mather L, ter Riet G. A systematic review of the clincal effectiveness of orlistat used for the management of obesity. Obesity Review. 2004;5:51–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2004.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Lalonde JK, Pindyck LJ, Walsh BT, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge eating disorder: a stable syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 163:2181–2183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2181. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen A, Lean M, Rossner S, Segal KR, Sjostrom L. Predictive value of early weight loss in obesity management with orlistat: an evidence-based assessment of prescribing deadlines. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27:103–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotland SC, Larocque M. Early treatment response as a predictor of ongoing weight loss in obesity treatment. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:601–614. doi: 10.1348/135910705X43750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL, Cairney J. What’s under the ROC? An introduction to receiver operating characteristics curves. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52:121–128. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ. Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:894–904. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TZ, Luborsky L, Andrusyna T. Sudden gains in recovering from depression: Are they also found in psychotherapies other than cognitive-behavioral therapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:444–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Geddes JR, Bhagwagar Z. Early onset of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant action. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1217–1223. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittengl JR, Clark LA, Jarrett RB. Validity of sudden gains in acute phase treatment of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:173–182. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Mickley D, Sysko R, Parides MK. Treatment of bulimia nervosa in a primary care setting. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:556–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BT, Sysko R, Parides MK. Early response to desipramine among women with bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:72–75. doi: 10.1002/eat.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Grilo CM. Psychiatric comorbidity in binge-eating disorder as a function of smoking history. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:594–599. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell EB, Cohen LR, Saelens BE, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Kraemer H. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: Time course and mechanisms of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatments of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;72:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Loeb KL, Walsh BT, Labouvie E, Petkova E, Lin X, Waternaux C. Psychological versus pharmacological treatments of bulimia nervosa: Predictors and processes of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:451–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Vitousek KM. Self-monitoring in the assessment of eating disorders. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:480–489. [Google Scholar]