Abstract

Sensory experience and the resulting synaptic activity within the brain are critical for the proper development of neural circuits. Experience-driven synaptic activity causes membrane depolarization and calcium influx into select neurons within a neural circuit, which in turn trigger a wide variety of cellular changes that alter the synaptic connectivity within the neural circuit. One way in which calcium influx leads to the remodeling of synapses made by neurons is through the activation of new gene transcription. Recent studies have identified many of the signaling pathways that link neuronal activity to transcription, revealing both the transcription factors that mediate this process and the neuronal activity–regulated genes. These studies indicate that neuronal activity regulates a complex program of gene expression involved in many aspects of neuronal development, including dendritic branching, synapse maturation, and synapse elimination. Genetic mutations in several key regulators of activity-dependent transcription give rise to neurological disorders in humans, suggesting that future studies of this gene expression program will likely provide insight into the mechanisms by which the disruption of proper synapse development can give rise to a variety of neurological disorders.

Keywords: activity-regulated transcription, synapse development, synaptic plasticity, CREB, MEF2, c-fos

INTRODUCTION

While intrinsic genetic programs play a critical role in shaping both early and postnatal neural development, extrinsic sensory cues are essential for the proper development of neural circuitry during early postnatal life. In addition to their role during early postnatal development, sensory experiences can lead to the formation of long-lasting memories and other adaptations in adult organisms. Both in infancy and in old age, the memories and adaptations that humans make in response to sensory experiences are ultimately mediated by experience-driven changes in neural connectivity. These changes are central to our everyday lives and are tragically disrupted in numerous psychiatric, neurological, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Complex Behaviors Are Altered by Sensory Experience Both During Development and in Adulthood

The acquisition of language provides an excellent example of the importance of sensory experience during development. Many studies examining the correlation between age and the ability to acquire new language skills have suggested that this ability progressively declines after early adolescence (reviewed in Doupe & Kuhl 1999). This observation prompted researchers to propose that there is a developmental critical period during which exposure to language is necessary for proper language development. Evidence for a critical period in vocal learning is supported by studies that have directly tested this hypothesis in songbirds. In many species, male songbirds learn one song during development and continue to sing only this song throughout their lives. In these cases, there is also a critical period during which the bird must hear its song to reproduce it properly as an adult (reviewed in Brainard & Doupe 2002). For example, white-crowned sparrows raised in isolation and subsequently exposed to recordings of their native song (after 100 days of age) never learn to sing the correct song.

Although many additional instances can be cited in which experience alters behavior most effectively when it occurs during early postnatal development, other adaptations that organisms make in response to sensory experience may remain quite plastic and reversible through adulthood. One clear example is the entrainment of circadian rhythms by light exposure. Neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)of the hypothalamus exhibit periodic oscillations in their firing rates (with cycles close to 24 h) that persist even when these cells are grown in dissociated cultures (reviewed in Reppert & Weaver 2002). In the intact brain, these cells coordinate their cycles with the solar cycle by receiving synaptic inputs from retinal ganglion neurons that detect light primarily with the photopigment melanopsin. In response to light, these retinal inputs alter the electrical activity of SCN neurons, thereby setting their pacemaking activity. Although we do not know yet how SCN neurons go on to orchestrate complex circadian behaviors, the importance of sensory input in setting the clock is well established.

Experience Can Alter Neural Circuitry Both During Early Postnatal Development and in Adulthood

These examples and many others illustrate the now well-accepted fact that humans and other organisms routinely alter their behaviors in response to experience. Ever since the pioneering work of Drs. David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel was published more than 40 years ago, neuro-biologists have appreciated that experience also plays an essential role in shaping neural connectivity. Specifically, a large number of studies have provided evidence that neuronal activity plays a critical role in (a) dendritic outgrowth, (b) synaptic maturation/potentiation, (c) synapse elimination, and (d ) synaptic plasticity in adult organisms.

Dendritic outgrowth

Dendrite elaboration is one of the first key steps in defining the synaptic inputs that a neuron will receive. Many distinct neuronal cell types in the brain have unique dendritic arbors that are suited to their function. Although we have known for quite some time that environmental stimuli can alter dendritic outgrowth, recent advances in fluorescent imaging have made it possible to examine in greater detail the interplay between environmental stimuli and dendritic growth. The Cline laboratory utilized in vivo time-lapse imaging in the tadpole Xenopus laevis to examine dendritic development in tectal neurons, which receive synaptic inputs from retinal ganglion cells. They noted that the dendritic arbors of these neurons elaborate as synapses begin to form onto tectal cells (Rajan & Cline 1998). As has been observed in other mammalian cell types, these experiments show that dendritic outgrowth is a highly dynamic process: Dendrites commonly sprout new branches and extend or retract existing branches. Blockade of N-methyl-d-aspartate subtype glutamate receptors (NMDARs), the predominant glutamate receptor in developing tectal neurons, slows both new dendritic branch addition and branch extension (Rajan & Cline 1998), whereas block-ade of either NMDARs or α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors (AMPARs) in more mature tectal cells (where both types of glutamate receptors can be found) destabilizes existing branches (Haas et al. 2006). Most strikingly, visual stimulation of young tadpoles, which increases synaptic activity onto tectal neurons, causes an increase in new branch addition and extension in an NMDA receptor– dependent manner (Sin et al. 2002). These experiments, which are supported by additional in vitro data (Redmond et al. 2002), suggest that synaptic activity promotes dendritic outgrowth.

Synapse maturation

As the dendrites of a neuron begin to elaborate, synapses form on these branches and then undergo an extensive maturation process. Although neuronal activity is not absolutely required for synapse formation (Verhage et al. 2000), sensory experience and synaptic activity are important for the subsequent maturation of synapses. On the presynaptic side of the neuromuscular junction and other synapses, this maturation involves the arborization and elaboration of the axon (Antonini & Stryker 1993, Sanes & Lichtman 1999). On the postsynaptic side, synapse maturation can be detected electrophysiologically as an increase in synaptic current. At central nervous system (CNS) synapses, such as the retinogeniculate synapse (the synapse made by retinal ganglion cell axons onto thalamic neurons), the AMPAR-mediated current is the predominant component of the postsynaptic response that is strengthened (Chen & Regehr 2000). A recent study of this synapse demonstrated that both spontaneous retinal activity and visual activity after eye opening are critical for the strengthening of the AMPAR-mediated current (Hooks & Chen 2006).

Synapse elimination

Although neuronal activity is critical for synapse maturation, in most circuits an excess of synapses initially forms, and only a subset of those synapses are strengthened while others are eliminated. This elimination process depends on sensory experience and synaptic activity. Drs. Hubel and Wiesel and others showed that in adult mammals the terminal axonal arbors of thalamic neurons that receive innervation from the retinal ganglion cells of the two eyes segregate from one another in layer IV of the primary visual cortex, forming ocular dominance columns (ODCs) (reviewed in Wiesel 1982). However, early in development, these axonal arbors overlap with one another. During early postnatal development these inputs segregate in a neuronal activity– dependent manner owing to the loss of synapses in the overlapped areas. Monocular deprivation in one eye causes inputs from the other eye to maintain more territory in layer IV, whereas blockade of input activity altogether by tetrodotoxin infusion into both eyes prevents ODC refinement (LeVay et al. 1980, Stryker & Harris 1986). A similar observation has also been made for retinogeniculate projections (Penn et al. 1998).

The role of synaptic activity in synapse elimination has been especially well characterized at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), the synapse made by motor neurons onto muscle cells. At the time of birth, individual muscle fibers are typically innervated by multiple motor neuron axons. However, during the first weeks of postnatal development, multiply innervated muscle fibers are converted to singly innervated fibers as a result of synapse elimination. This process occurs gradually, with many inputs decreasing in synaptic strength as a single input increases its strength (Colman et al. 1997). A similar skewing in synaptic inputs has been detected during the development of the retinogeniculate synapse and other CNS synapses (Chen & Regehr 2000). Preventing individual motor neuron axons from activating postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors leads to the elimination of that input, suggesting that axons must be effective in depolarizing the muscle in order to be maintained (Buffelli et al. 2003). A number of studies have also shown that blockade of synaptic activity throughout an entire junction prevents synapse elimination, whereas increasing activity accelerates the process (reviewed in Sanes & Lichtman 1999). In addition, driving synchronous activity in all the fibers that innervate a single NMJ prevents synapse elimination, indicating that the unequal ability of axons to activate the muscle is essential for developmental input elimination (Busetto et al. 2000).

Synaptic plasticity

Although there are many examples where experience shapes neural connectivity specifically during a critical period in development, it is clear that experience can also alter neural connectivity in the adult brain. Much of this evidence comes from studies of associative learning, including Pavlovian fear conditioning, a paradigm in which an electrical shock to the foot is administered to an animal shortly after an auditory tone is presented. After several repetitions, animals learn that the tone and shock are paired and display a fear response (involving freezing, etc.) when presented with the tone even in the absence of the electrical shock. Recordings from the dorsolateral nucleus of the amygdala (dLA), which receives direct inputs from the auditory system and is required for this form of learning, have shown that neurons in this area have an increased firing rate in response to the tone after associative learning has occurred (reviewed in Maren & Quirk 2004). This increase in firing rate is likely due to alterations in synaptic connectivity because it shares many characteristics with long-term potentiation (LTP), an activity-dependent model for synaptic strengthening that can be induced by high-frequency stimulation of the afferents to the dLA in a slice preparation (reviewed in Maren 2005). The mechanisms underlying LTP at this synapse and others (most notably the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse in the hippocampus) have been studied in great detail and involve the activity-dependent insertion of AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic membrane as well as the growth of new dendritic spines, which serve as the sites of most excitatory CNS synapses (Engert& Bonhoeffer 1999, Malinow & Malenka 2002). In contrast, long-term depression (LTD), an activity-dependent model for synaptic weakening in ma-ture neural circuits, involves removing AMPA receptors from the cell membrane and deconstructing existing dendritic spines (Nagerl et al. 2004).

Activity-Dependent Gene Expression: Importance in the Development of Neural Connectivity and Human Neurological Development

The cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie these experience-driven changes in neural connectivity have been the subject of intense investigation in recent years. Sensory experience results in neurotransmitter release at synapses within a neural circuit, which in turn leads to membrane depolarization and calcium influx into individual neurons. This action then triggers a wide variety of cellular changes within these neurons, which are capable of altering the synaptic connectivity of the circuit. Some of these changes, such as the activation of calcium-sensitive signaling cascades, which lead to posttranslational modifications of proteins, or the regulation of mRNA translation, resulting in the production of new proteins, occur locally at the sites of calcium entry and play critical roles in altering synaptic function in a synapse-specific manner (reviewed in Malinow & Malenka 2002, Sutton & Schuman 2006).

In addition to these local effects, calcium influx into the postsynaptic neuron can alter cellular function by activating new gene transcription. Calcium influx activates a number of signaling pathways that converge on transcription factors within the nucleus, which in turn control the expression of a large number of neuronal activity-regulated genes. Recent work has revealed a number of the signaling pathways that mediate activity-dependent transcription and has identified their roles in experience-dependent neural development and plasticity. The remaining portion of this review discusses the signal transduction pathways by which neuronal activity regulates the activity-dependent gene expression program and summarizes recent findings that have clarified the function of this signaling network.

The work reviewed here, together with recent advances in human genetics, has revealed links between the signaling networks that control activity-dependent transcription and human neurological disorders, such as mental retardation and autism-spectrum disorders. The identification of these links highlights the importance of this subject and raises the possibility that future studies in this field will not only provide insights into the mechanisms that control activity-dependent brain development but may also enhance our understanding of how the disruption of proper brain development can lead to a wide variety of neurological disorders.

CHARACTERIZATION OF THE NEURONAL ACTIVITY-REGULATED GENE EXPRESSION PROGRAM

Early Insights: c-fos as the Prototypical Immediate Early Gene

The observation that extracellular stimuli can trigger rapid changes in gene transcription came from studies of quiescent fibroblasts stimulated by growth factors to reenter the cell cycle. The addition of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) or other growth factors to quiescent 3T3 fibroblasts led to the extremely rapid induction of the c-fos proto-oncogene (Greenberg & Ziff 1984). The increased transcription of c-fos and other genes, termed immediate early genes (IEGs), occurs rapidly (in the case of c-fos, within ∼5 min) and transiently (for c-fos, undetectable ∼30 min later) and does not require new protein synthesis. A separate group of extracellular stimuli-responsive genes (discussed below) is induced with slower kinetics, often showing peak transcriptional activity several hours after stimulation.

The importance of stimulus-induced transcription in neuronal cells was first suggested by the observation that c-fos transcription could be induced in response to a number of different stimuli in neuronal cell types. In the rat pheochromocytoma cell line PC12, activation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, as well as an increase in the concentration of extracellular potassium chloride that leads to membrane depolarization and calcium influx via l-type voltage-gated calcium channels (l-VGCCs), triggers c-fos transcription (Greenberg et al. 1986). Upregulation of c-fos in neurons of the intact brain was subsequently observed in specific brain regions in response to seizures and a wide range of physiological stimuli (Morgan et al. 1987). For instance, neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord show increased Fos immunoreactivity in response to various modes of tactile sensory stimulation (Hunt et al. 1987), whereas neurons in the SCN show increased Fos expression upon visual stimulation (Rusak et al. 1990). In fact, the expression of c-fos and other IEGs is now routinely used to mark neurons that have been recently activated. These studies indicate that IEGs are induced in individual neurons in response to physiological levels of neurotransmitter release.

The observation that the c-fos mRNA is robustly induced by synaptic activity resulting from sensory experience raised the possibility that the Fos protein, which together with Jun family members comprises the AP-1 transcriptional complex, is critical for the adaptive responses that organisms make in response to experience. Indeed, analyses of mice harboring a brain-specific deletion of the c-fos gene have shown that these animals display deficits in synaptic plasticity as well as defects in several forms of learning and memory (Fleischmann et al. 2003). Loss of Fos-dependent transcription can give rise to additional behavioral deficits because mice lacking the gene encoding the fos family member FosB display a defect in nurturing behaviors, as well as altered sensitivity to drugs of abuse, such as cocaine (Brown et al. 1996, Hiroi et al. 1997). Because the presence of a newborn pup induces FosB expression in the preoptic area of the mother’s hypothalamus, while chronic cocaine administration induces FosB expression in the striatum, it is possible that the lack of an appropriate transcriptional response in these brain circuits in FosB null mice leads to altered behavioral responses in these animals.

The Activity-Regulated Gene Expression Program in Neurons: Genes that Directly Regulate Synaptic Function

Since the discovery of c-fos induction, many additional activity-regulated genes have been discovered (Bartel et al. 1989, Nedivi et al. 1993, Saffen et al. 1988, Yamagata et al. 1993). However, because of technical limitations, a genome-wide analysis of activity-dependent gene expression has only recently become possible. High-density oligonucleotide microarrays and differential analysis of library expression (DAzLE) have been used to identify genes in cortical and hippocampal neurons whose expression is acutely altered in response to membrane depolarization, NMDA application, LTP induction, and seizure induction (Altar et al. 2004, Hong et al. 2004, Li et al. 2004, Park et al. 2006). These experiments confirm the presence of several hundred neuronal activity-regulated genes in these cells. Although many neuronal activity-regulated genes, such as c-fos, encode transcription factors, a large number of these genes encode proteins that have important functions in dendrites and synapses and are likely to regulate circuit connectivity directly. Detailed studies investigating the functions of a few of these neuronal activity-regulated genes have yielded insights into how this activity-regulated transcriptional program controls neuronal development.

Candidate plasticity gene 15 (Cpg15)

A number of neuronal activity-regulated genes encode cell surface proteins or secreted proteins that are transported to dendrites and synapses. Several of these proteins promote both dendritic outgrowth and synapse maturation. For instance, expression of cpg15 (also called neuritin) enhances dendritic outgrowth, presynaptic axonal elaboration, and AMPA receptor insertion in Xenopus tectal neurons (Cantallops et al. 2000, Nedivi et al. 1998). In these experiments, dendritic outgrowth and synapse maturation were enhanced in neurons adjacent to those overexpressing CPG15. Because CPG15 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein, its maturation-promoting effects are likely mediated by intercellular interactions.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

The activity-regulated gene bdnf encodes a neurotrophin that is secreted at synapses in an activity-dependent manner and can bind to tyrosine kinase receptor B (trkB) and p75 neurotrophin receptors located in both pre-and postsynaptic membranes. Like CPG15, the induction of BDNF promotes both dendritic outgrowth and synapse maturation, but recent evidence suggests that the effects of BDNF are more complex. Bath application of BDNF to organotypic cortical slices has cell type–specific effects on dendritic outgrowth: Where as BDNF application enhances dendritic outgrowth in layer II/III and layer IV neurons, it can inhibit outgrowth in layer VI neurons (McAllister et al. 1995, 1997; Niblock et al. 2000). Similar seemingly contradictory results can be found within a single cell. Retinal ganglion cells in Xenopus display enhanced dendritic outgrowth when BDNF is applied to the distal tips of their axons and decreased dendritic outgrowth when BDNF is applied locally to the dendrites (Lom et al. 2002). These results suggest that BDNF secreted from different sources might signal differently (either via a different receptor or different downstream effectors) to elicit different effects. Given that the expression and secretion of BDNF are normally tightly controlled in neurons, bath application of BDNF might not recapitulate the effects of endogenous BDNF. Nevertheless, studies of a bdnf conditional knockout mouse confirm that BDNF regulates dendritic outgrowth in layer II/III cortical neurons (Gorski et al. 2003). Moreover, a decrease in dendritic complexity was also observed in a bdnf knock-in mouse designed to carry a valine-to-methionine amino acid substitution at valine-66 (val66met) in the BDNF protein (Chen et al. 2006). Because a single nucleotide polymorphism found in the human bdnf gene, resulting in the val66met substitution, confers susceptibility to memory deficits and other neurological and psychiatric disorders (Bath & Lee 2006), these data suggest that abnormalities in neural connectivity may underlie the neurological deficits found in patients carrying the val66met polymorphism.

The role of BDNF in synapse maturation is also complex. Numerous studies have reported that application of recombinant BDNF to neurons can lead to an increase in synaptic strength (Kang & Schuman 1995, Kovalchuk et al. 2002, Lohof et al. 1993). Investigators have reported both short- and long-term effects (minutes vs. hours) of BDNF application on synaptic strength and have suggested that both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms underlie the strengthening process. In addition, in several instances, BDNF application strengthens only select synapses or synapses that have been recently activated (Kovalchuk et al. 2002, Schinder et al. 2000). The reasons for these synapse-specific differences are not yet clear, although a better understanding of the complexity of BDNF processing and signaling may eventually provide an answer. Analyses of bdnf knockout animals demonstrated a decrease in basal synaptic transmission in some genetic backgrounds and a deficit in tetanus-induced LTP at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse in the hippocampus in several backgrounds (Korte et al. 1995, Patterson et al. 1996). However, synapse and LTP deficits in a total knockout mouse could arise from earlier developmental abnormalities, such as altered dendritic outgrowth or neuronal survival.

For this reason, a recent study of a trkB receptor conditional knockout mouse provides some additional insight into the importance of neurotrophins for synaptic development. Deletion of TrkB receptors after synaptic development has no effect on the number of synapses in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, but deletion of TrkB earlier leads to clear deficits in synaptic development that arise within the first weeks after birth (Luikart et al. 2005). Presy-naptic loss of TrkB decreases the density of axon varicosities and presynaptic markers, whereas postsynaptic loss of TrkB decreases the density of dendritic spines and postsynaptic markers and leads to clear electrophysiological defects. These results suggest that BDNF has both pre-and postsynaptic modes of action, although in interpreting these results, one must consider that neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) also binds to the TrkB receptor and BDNF has additional receptors, such as p75.

In fact, recent experiments suggest that BDNF may promote synapse weakening by a TrkB-independent mechanism. The BDNF protein is initially synthesized as a precursor protein, termed proBDNF, which is proteolytically cleaved to form mature BDNF (mBDNF). Both forms of BDNF appear to be secreted from neurons, from either pre- or postsynaptic sites (Hartmann et al. 2001, Kohara et al. 2001), but they bind different receptors: proBDNF acts through the p75 receptor, whereas mBDNF signals via the TrkB receptor (Teng et al. 2005). The studies discussed above utilized mBDNF application and TrkB deletion and support a role for this signaling pathway in synaptic strengthening. However, application of proBDNF to neurons enhances LTD (Woo et al. 2005). In addition, hippocampal neurons in p75 receptor knockout mice display an increase in dendritic spine density, a phenotype opposite to the TrkB knockout animals (Zagrebelsky et al. 2005). These results support the idea that a proBDNF-p75 signaling pathway may negatively regulate excitatory synapse development, though this possibility needs to be further explored.

Class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules

In addition to the proBDNF-p75 signaling pathway, a separate group of neuronal activity-regulated signaling molecules have been suggested to restrict synapse number. Corriveau et al. (1998) identified a cDNA encoding class I MHC antigen in a screen for activity-regulated genes in the visual system, and subsequent experiments showed that mice with reduced levels of surface class IMHC display deficits in retinogeniculate eye-specific layer refinement, a process that involves synapse loss (Huh et al. 2000). Because MHC molecules have been studied primarily in the immune system, the molecular mechanisms by which the MHC proteins control synapse number are not yet clear. However, recent work in cultured hippocampal neurons suggests that class I MHC proteins are present in postsynaptic membranes and also negatively regulate excitatory synaptic function in these neurons (Goddard et al. 2007).

Homer1a and serum-inducible kinase (SNK)

Further studies of the activity-regulated gene expression program in hippocampal neurons have revealed that, in addition to cell membrane and secreted proteins, neuronal activity induces the expression of genes whose products regulate intracellular signaling pathways in the postsynaptic compartment. Two recent reports highlight the ability of the activity-regulated gene expression program to destabilize synapses by regulating postsynaptic signaling. Although studies have not yet shown that these molecules mediate synapse elimination in vivo, they represent good candidates that may regulate this process. The first report describes studies of Homer1a, an activity-regulated gene product produced by the homer1 gene locus. Studies of this gene revealed a special feature of activity-regulated transcription. In addition to promoting the transcription of the homer1 gene, calcium influx causes a switch in homer1 pre-mRNA processing. This switch promotes the use of a premature polyadenylation site in the fifth intron of the homer1 gene, which results in the activity-dependent production of a truncated mRNA encoding only the N-terminus of Homer1 (Bottai et al. 2002). Whereas full-length Homer1 proteins that are present in the absence of neuronal activity form dimers via their C-terminal coiled-coil domains and act as scaffolding molecules, bridging synaptic molecules that bind to their N-terminal EVH domains, Homer1a encodes only the EVH domain. This truncated protein interferes with full-length Homer1’s function and thereby disrupts synaptic protein complexes and reduces synapse number (Sala et al. 2003). A second report describes the characterization of another activity-regulated gene product, the serum-inducible kinase (SNK). SNK phosphorylates SPAR, a postsynaptic signaling molecule that promotes dendritic spine growth. Phosphorylation of SPAR leads to its ubiquitylation, which in turn promotes SPAR degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome complex (Pak & Sheng 2003). The loss of SPAR results in the desta-bilization of synapses. Thus, SNK induction triggers SPAR phosphorylation and degradation, leading to a decrease in synapse number.

Activity regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc)

Activity-regulated gene products can alter synaptic function not only by promoting synapse loss but also by directly regulating the number of AMPA receptors inserted in the postsynaptic membrane. Studies of the activity-regulated gene product Arc have shown that this protein interacts with endophilins and promotes the internalization of AMPA receptors, thus inhibiting the number of functional glutamatergic synapses formed onto neurons (Chowdhury et al. 2006, Rial Verde et al. 2006, Shepherd et al. 2006). In contrast with many mRNAs, the subcellular localization of the arc mRNA is tightly controlled. After arc mRNA expression is induced by increased levels of synaptic activity, arc mRNAs are localized or stabilized specifically at synapses that were activated (Steward et al. 1998). Although this effect is quite striking, this property of the arc mRNA has not yet been related to the Arc protein’s ability to promote AMPA receptor internalization. However, AMPA receptor internalization is likely enhanced only at synapses where arc mRNAs are localized and translated. Although these results suggest a mechanism by which the regulation of the subcellular localization of mRNAs produced in response to activityregulated transcription can lead to the modification of specific synapses, additional experiments will be required to determine not only the effect of neuronal activity on arc mRNA localization but also whether the increased presence of arc mRNAs at synapses correlates with an increase in Arc protein and an increase in AMPAR internalization.

MicroRNA-134 (miR-134)

Additional studies of the activity-regulated transcriptional program have recently uncovered a new mechanism by which calcium-dependent gene induction alters the function of specific synapses. This work stems from the observations that the translation of select mRNAs can occur at individual synapses (Sutton & Schuman 2006). One way in which this might work is through the actions of microRNAs (miRNAs), which are small RNAs known to inhibit the translation of mRNAs that have nucleotide sequences closely matching the miRNA. The level of miR-134 is increased by neuronal activity (Schratt et al. 2006). In neurons, miR-134 expression restricts excitatory synapse development, whereas its inhibition promotes dendritic spine growth. Because miR-134 localizes to dendrites and synapses, it may act locally to control mRNA translation and thereby control circuit development. Indeed, miR-134 represses the translation of the limk1 mRNA at synapses until exposure of synapses to BDNF relieves miR-134-dependent repression. Therefore, although the activity-dependent transcription of miR-134 and other miRNAs likely results in miRNA expression throughout the cell, if the mRNA target of the miRNA is localized to synapses, then the miRNA could be a component of the local mRNA translation machinery that allows proteins to be translated in a synapse-specific manner.

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS UNDERLYING THE TRANSCRIPTIONAL CONTROL OF ACTIVITY-REGULATED GENES

Only a small number of the activity-regulated genes have been studied at the level of detail described above. Additional work will be necessary to reveal the neuronal functions of the large number of uncharacterized activity-regulated gene products. Nonetheless, the studies carried out so far demonstrate that this transcriptional program is critical in coordinating both dendritic and synaptic remodeling. Because this program is important for neuronal development and function, the transcriptional mechanisms that control the expression of these genes have been intensely investigated. These mechanistic studies have focused primarily on a limited number of activity-regulated genes, including c-fos and bdnf. We review the key discoveries that revealed how calcium influx leads to the transcription of these and other genes. In addition to uncovering the mechanisms underlying activity-dependent transcription, these studies have identified the transcription factors that coordinate the expression of numerous activity-regulated genes.We also discuss research aimed at understanding the functions of these transcriptional regulators in neuronal development.

Lessons from c-fos: The Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP) Response Element Binding Protein (CREB) in Activity-Regulated Transcription

To understand how calcium influx leads to an increase in the transcription of c-fos, bdnf, and other genes, investigators first identified cis-acting regulatory elements in the proximal promoters of these genes. The discovery of the key regulatory elements paved the way for the identification of the transcription factors that bind these elements, as well as the upstream signaling cascades that lead to the calcium-dependent modification of these factors. This approach, which essentially traces the calcium-regulated signaling pathway in reverse, has elucidated many of the signaling mechanisms that link calcium influx through the neuronal cell membrane to transcriptional activation within the nucleus. As many of these pathways have now been uncovered, more recent experiments aimed at characterizing these transcriptional networks have involved genomic and proteomic approaches that were previously unavailable.

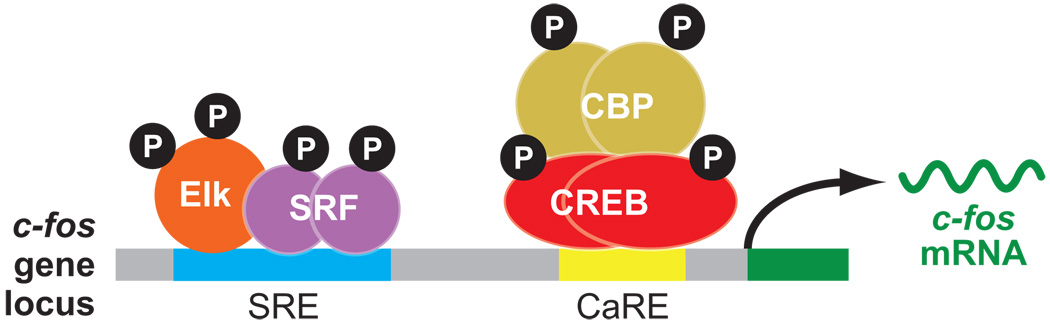

The first cis-acting regulatory element that was shown to regulate calcium-dependent transcription is located within 100 base pairs of the c-fos transcriptional start site and was termed the calcium response element (CaRE) (Figure 1). The CaRE in the c-fos promoter is similar in sequence and function to the cAMP response element (CRE) initially identified in the somato-statin gene promoter (Montminy et al. 1986). DNA affinity chromatography was used to purify the nuclear protein that bound to the CRE of somatostatin, which subsequently allowed investigators to clone the cDNA encoding CREB and demonstrate that this transcription factor binds to the CRE and mediates transcription in response to elevated cAMP levels (Gonzalez et al. 1989, Montminy & Bilezikjian 1987).

Figure 1.

Regulatory mechanisms that control calcium-dependent c-fos transcription in neurons. At least two separate cis-acting regulatory elements are critical for calcium-dependent c-fos transcription: the CaRE and the SRE. These elements, as well as the protein complexes that are recruited to each of these elements, are shown. The transcribed region (dark green) and the c-fos mRNA produced by the c-fos gene (dark green) are also shown.

c-fos promoter deletion analysis in PC12 cells identified the CaRE in the c-fos promoter as the first regulatory element capable of conferring calcium-dependent gene activation (Sheng et al. 1988). Purification of the transcription factor that binds to the c-fos CaRE revealed that this protein is identical to CREB and led to the conclusion that CREB mediates both calcium- and cAMP-dependent transcription within the nucleus (Sheng et al. 1990). A mechanism for cAMP/calcium-dependent transcription was suggested by the finding that elevated levels of cAMP lead to CREB phosphorylation at serine-133 and mutation of this site abolishes CREB-dependent reporter gene activation (Gonzalez & Montminy 1989). Membrane depolarization-induced calcium influx into PC12 cells also causes CREB serine-133 phosphorylation, and phosphorylation of this residue is required for calcium-dependent CREB activation; however, the kinase that phosphorylates CREB is likely different in this case (Sheng et al. 1991). The identity of the CREB serine-133 kinases has been the subject of many studies. Although an exhaustive review of this literature is not possible here (reviewed in Lonze & Ginty 2002), protein kinase A likely mediates cAMP-dependent phosphorylation, and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinases (CamKs), ribosomal S6 kinases (RSKs), and mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinases (MSKs) likely mediate calcium-dependent phosphorylation. Importantly, the development of antisera that recognize the CREB protein only when phosphorylated at serine-133 allowed investigators to show that CREB is phosphorylated in neurons in the brain in response to physiological levels of neurotransmitter release (Ginty et al. 1993).

The discovery of CREB binding to the c-fos CaRE and to CaREs within the regulatory regions of other activity-regulated genes prompted researchers to investigate the function of the CREB protein in neuronal development. It is important to note that investigating the function of a transcription factor represents an approach that is distinct from examining the function of a single activity-regulated gene. Alterations in CREB levels (either loss- or gain-of-function) will likely alter the expression of its numerous activity-regulated target genes and reveal the function(s) of this transcriptional program as a whole.

These experiments have revealed a role for CREB in both dendritic outgrowth and synaptic potentiation. Consistent with the Xenopus work described above, membrane depolarization-induced calcium influx or stimulation with other agents that enhance synaptic activity leads to an increase in dendritic outgrowth in cultured cortical or hippocampal neurons (Redmond et al. 2002, Wayman et al. 2006). In these cases, both CaMK activation and CREB activation are required for activity-dependent dendritic outgrowth. The CREB targets that mediate this effect likely include cpg15, bdnf, miR-132, and wnt-2, although many more likely remain to be discovered (Fujino et al. 2003, Tao et al. 1998, Vo et al. 2005, Wayman et al. 2006).

Evidence supporting a role for CREB in synaptic potentiation originally comes from work in the snail Aplysia californica (reviewed in Kandel 2001). In mature snails, a physical touch to the siphon activates sensory neurons that innervate motor neurons, which trigger a defensive response where the animal withdraws its gill. This gill withdrawal reflex is enhanced when the tail of the animal is shocked before the siphon is touched. This process, called sensitization, is mediated by serotonergic inputs to the sensory neurons that are activated by the shock to the tail. Sensitization presumably allows the organism to amplify its withdrawal response under stressful environmental conditions. When the tail is shocked a single time, sensitization lasts only for minutes or hours. However, when the tail is shocked four or five times, sensitization can last for days or weeks. Whereas short-term sensitization involves a protein synthesis–independent increase in neuronal excitability caused by serotonin release onto the sensory neurons, long-term sensitization (caused by repeated serotonin release onto the sensory neurons)requires new gene transcription and protein synthesis and involves increased arborization and synaptic growth in sensory neurons (Bailey & Chen 1983, Montarolo et al. 1986). Studies utilizing CRE oligonucleotide injections have suggested that Aplysia CREB-1, which is activated in sensory neurons when the tail is stimulated repeatedly, is required for synaptic growth and long-term sensitization (Dash et al. 1990, Kaang et al. 1993).

Because Aplysia sensitization can be studied in a cell culture model of this circuit, Martin et al. (1997) tested the axonal branch specificity of long-term sensitization. When a sensory neuron extends two branches and innervates two separate motor neurons, it is possible to apply serotonin repeatedly to one branch of the sensory neuron and mimic long-term sensitization. This protocol leads to long-term synaptic strengthening along the stimulated branch (also called long-term facilitation) but has no effect on synapses along the other branch. However, when a single pulse of serotonin on the second branch (which normally elicits only a short-term response) is paired with long-term facilitation of the first branch, both branches display a long-term response. Thus, the induction of long-term facilitation at one synapse converts a short-term response at a separate synapse to a long-term response. Because this process requires new gene transcription, activity-regulated gene products are likely distributed throughout the cell but utilized only at synapses that have been stimulated with serotonin. This process, termed synaptic capture, also occurs during synapse-specific LTP of synaptic inputs formed onto CA1 pyramidal neurons in the mammalian hippocampus (Frey & Morris 1997).

These experiments have been influential in establishing a role for CREB in plasticity, as well as in learning and memory. However, CREB’s role in mammalian synaptic plasticity has been more controversial. The role of CREB and other factors in LTP at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse in the hippocampus has been the subject of considerable interest because plasticity at this synapse as well as others in the hippocampus is critical for the acquisition of certain types of long-lasting memories, including forms of spatial memory and episodic memory. Although some studies have reported a role for CREB in LTP at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse in the hippocampus (Bourtchuladze et al. 1994), subsequent studies have not reproduced this finding (Balschun et al. 2003, Gass et al. 1998). Moreover, any LTP deficit in a total knockout could be due to developmental defects caused by deletion of CREB family members, such as altered dendritic outgrowth or increased neuronal apoptosis. Nevertheless, one result that supports a role for CREB in mammalian plasticity comes from studies of a transgenic mouse expressing constitutively active CREB (VP16-CREB; Barco et al. 2002). In this animal, a stimulus that normally elicits a short-term form of LTP at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse leads to a long-lasting form of LTP. These results are consistent with the Aplysia work, suggesting that CREB activation specifically strengthens recently activated synapses.

Given evidence that CREB plays a role in neural circuit development and a wide range of other processes during mammalian development, additional experiments were carried out to determine the mechanism by which serine-133 phosphorylation enhances CREB tran-scriptional activity. These experiments identified additional transcriptional regulators that control activity-dependent gene expression. The CREB binding protein (CBP) was identified in a screen for proteins that bind specifically to phosphorylated CREB and was shown to be critical for stimulus-induced CREB activation (Chrivia et al. 1993). Although CBP and p300 (its close mammalian paralog) are ubiquitous transcriptional coactivators, the finding that mutations in the cbp gene in humans causes Rubenstein-Taybi syndrome, a severe form of mental retardation, suggests a unique role for CBP in the brain (Petrij et al. 1995). Like CREB, CBP itself undergoes calcium-dependent phosphorylation in neurons (Hu et al. 1999, Impey et al. 2002). However, it is unclear how phosphorylation affects CBP function.

CBP and p300 are large multidomain proteins that possess intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. Their recruitment to the CaRE in the c-fos promoter could promote c-fos transcription either by (a) recruiting general transcription machinery and RNA polymerase II to the c-fos promoter via their multiple protein-protein interaction domains or (b) promoting acetylation of the histone N-terminal tails, which is likely required for gene activation. Although both mechanisms likely occur, recent studies have provided compelling support for the acetylation hypothesis. First, several studies have shown that stimuli known to induce activity-dependent gene transcription lead to an increase in histone acetylation at the c-fos promoter and at other activity-regulated gene promoters (Tsankova et al. 2004). Second, in a transgenic mouse that expresses a mutant version of CBP rendered HAT-inactive by two point mutations, c-fos induction is impaired (Korzus et al. 2004). Expression of the transgene, which is predicted to act dominantly to interfere with endogenous CBP, is limited to neurons in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in this animal. These mice are also deficient in specific aspects of long-term memory. A particularly nice feature of this experiment is that the phenotypes can be reversed both by suppression of transgene expression (using a tetracycline-inducible system) or by treatment with the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA), suggesting that the phenotypes are due to the acute loss of activity-dependent histone acetylation rather than to developmental defects.

In contrast with CREB serine-133, which becomes phosphorylated upon exposure of neurons to a wide variety of extracellular stimuli, serines-142 and −143 of CREB are phosphorylated specifically in response to stimuli that induce calcium influx into neurons (Kornhauser et al. 2002). Mutations of CREB serine-142 and serine-143 to alanines significantly attenuate calcium-dependent CREB activation but not cAMP-dependent CREB activation.CREB phosphorylation at serine-142 inhibits CREB’s interaction with CBP, suggesting that phosphorylation of these residues in response to calcium influx might activate a novel CREB-dependent signaling pathway (Kornhauser et al. 2002). Generation of a knock-in mouse harboring a serine-to-alanine mutation at serine-142 demonstrates that phosphorylation of this site is important in vivo, as light entrainment of the mouse circadian cycle and expression of the clock gene mPer1(processes that require CREB activation in SCN neurons) are disrupted in this mutant (Gau et al. 2002). Assuming that CREB phosphorylated at serine-133 and serine-142 does not interact with CBP, it will be worthwhile to identify the cofactors that are recruited to CREB in response to this novel mode of activation.

Recently, a screen for additional activity-regulated transcription factors revealed other CREB- and CBP-interacting neuronal transcription factors. By fusing a cDNA library to the Gal4 DNA binding domain and testing pools of cDNAs for calcium-dependent activation of a Gal4-dependent reporter gene in primary neurons, several putative activity-regulated transcription factors were identified (Aizawa et al. 2004). Although the specific signaling pathways upstream of these factors, which include CREST, NeuroD2, and Lmo4, are not yet fully characterized, CREST is known to interact with CBP and Lmo4 interacts with CREB (Aizawa et al. 2004; Kashani et al. 2006). Analyses of the knockouts for these three factors indicate that they play important roles in neuronal circuit development (Aizawa et al. 2004, Ince-Dunn et al. 2006, Kashani et al. 2006).

Lessons from c-fos : Serum Response Factor (SRF) in Activity-Regulated Transcription

Work on the CaRE in the c-fos promoter has yielded a significant amount of information regarding the mechanisms underlying activity-dependent transcription and its importance in circuit development. In addition to the CaRE, however, promoter deletion analyses identified a second regulatory element in the c-fos promoter, termed the serum response element (SRE), which mediates the c-fos transcriptional response to serum application (Greenberg et al. 1987, Treisman 1985) (Figure 1). Subsequent experiments showed that the SRE is also required for calcium-dependent c-fos transcription (Misra et al. 1994). DNA affinity chromatography yielded the purification of the serum response factor (SRF) and allowed for the subsequent cloning of its cDNA (Norman et al. 1988, Treisman 1987). However, eventually studies found that more than one protein binds to the SRE. A separate DNA affinity purification resulted in the identification of a ternary complex containing the SRE, SRF, and a separate protein later named Elk-1 (Shaw et al. 1989). Closer analysis of the SRE showed that it consists of an inner DNA sequence required for SRF binding, as well as a 5′ sequence dispen-sible for SRF binding but necessary for Elk-1 binding. Elk-1 interacts with SRF and requires the presence of both SRF and its own DNA binding site to form a stable ternary complex. In addition to Elk-1, several other related factors (known as ternary complex factors, all of which contain Ets-domain DNA binding domains) were identified that also form a stable ternary complex with the SRE and SRF (Posern & Treisman 2006). Both SRF and a ternary complex factor must bind to the SRE to induce a maximal transcriptional response upon calcium influx into neurons, though binding of SRF alone can confer some calcium-dependent activation (Xia et al. 1996).

Calcium influx into neurons leads to the phosphorylation of both SRF and Elk-1. Phosphorylation of SRF at serine-103 by RSKs and CamKs enhances binding of SRF to the c-fos promoter (Rivera et al. 1993). Elk-1 phosphorylation by extracellular signal-related kinases (ERKs) is critical for glutamate-mediated c-fos activation, although the mechanism(s) by which phosphorylation activates Elks remains unclear (Xia et al. 1996). In addition, serum stimulation activates SRF via a unique signaling pathway in which Rho GTPases promote actin polymerization, followed by the recruitment of a distinct set of ternary complex factors to SRF (Posern & Treisman 2006). Although the relevance of this signaling pathway to neuronal activity-dependent gene expression remains unclear, actin polymerization in dendritic spines could signal to the nucleus through this type of pathway. The finding that a large number of cofactors work together with SRF indicates that SRF may mediate neuronal responses to a variety of different stimuli.

Examination of the role of SRF in synapse development and function has recently been facilitated by the generation of mice carrying conditional deletions of the srf gene. Although these studies support a role for SRF in the activity-dependent transcription of c-fos and other activity-regulated genes, experiments aimed at dissecting the biological function of SRF have yielded conflicting results. Whereas a specific deficit in LTP at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapse in the hippocampus was reported in one strain, a separate study indicated that srf conditional knockouts have deficits in both LTP and LTD at this synapse (Etkin et al. 2006, Ramanan et al. 2005). The interpretation of these results is complicated by the fact that these animals may also have axonal targeting defects in the hippocampus (Knoll et al. 2006). These studies indicate an important role for SRF in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, but further studies will be necessary to clarify the function of SRF and its cofactors in neural circuit development and plasticity.

Lessons from bdnf : Multiple Promoters, Late Transcriptional Response, and Calcium Specificity

The transcription of c-fos and many other IEGs increases in many cells of the body in response to extracellular factors that induce proliferation or differentiation of the cells. These IEGs mediate cellular responses to changes in the cell’s environment that vary depending on the cell’s developmental history. In the nervous system, c-fos and other IEGs likely play specific roles in neuronal differentiation as well as in synaptic development and plasticity.

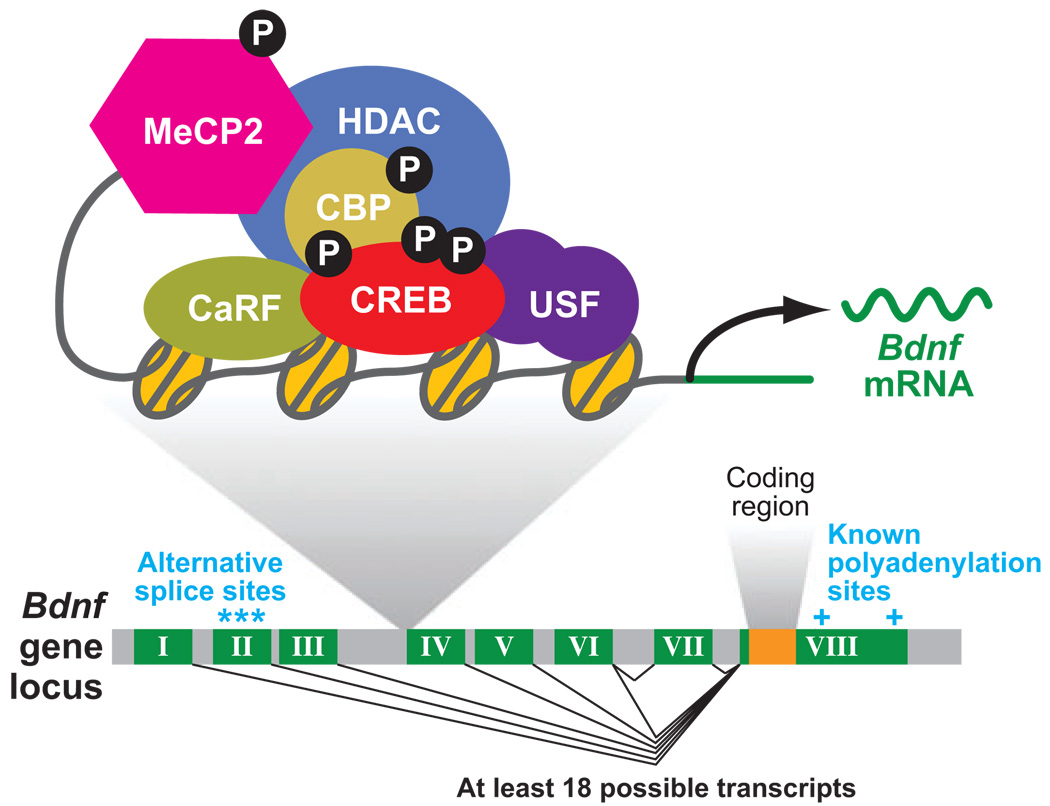

In contrast with c-fos and a variety of other IEGs that are induced in a wide range of cell types, recent studies have identified a subset of genes that is activated specifically in response to excitatory synaptic transmission that triggers calcium influx into the postsynaptic neuron. One gene whose expression is specifically induced by neuronal activity in neurons is bdnf, which encodes a neurotrophin that plays a critical role in many aspects of neural development (discussed above). The level of the bdnf mRNA increases in neurons in response to a variety of physiological stimuli, such as fear conditioning and seizure induction (Rattiner et al. 2004, Timmusk et al. 1993). As with c-fos, the induction of bdnf mRNA is likely due to an increase in transcription of the bdnf gene (Tao et al. 1998). However, unlike the c-fos gene, the genomic structure of bdnf is complex (Figure 2). To date, as many as nine distinct promoters in the mouse bdnf gene have been reported (Aid et al. 2007), six of which have been well characterized (Timmusk et al. 1993). Transcripts initiated at each of these promoters splice from their first exon to a common downstream exon, which contains the entire open reading frame encoding the BDNF protein. Because there are two polyadenylation sites in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the common bdnf exon and additional alternatively spliced exons, a large number of distinct bdnf transcripts can be produced. The biological importance of this diversity remains a mystery, though the fact that each of the bdnf transcripts encodes an identical protein suggests that the distinct 5′ and 3′ UTRs of bdnf mRNAs likely confer additional regulation of BDNF production beyond its transcriptional regulation. For instance, the distinct bdnf mRNAs could be localized to different subcellular compartments or translated into proteins under different cellular conditions. It is tempting to speculate that this diversity could explain how BDNF can control such a large number of distinct processes during nervous system development.

Figure 2.

The genomic structure and transcriptional regulation of bdnf. The genomic structure of the mouse bdnf gene is shown here. Exons are depicted in dark green and their numbers are indicated by roman numerals; introns are shown in gray. At least six alternative promoters can be clearly detected at this gene (although more may exist—see text for a more detailed explanation). Each of these promoters controls the expression of a unique mRNA that consists of one unique exon (numbered I through VI) that is directly spliced to a common exon (exon VIII), which contains the entire bdnf coding region (orange). The diversity of bdnf transcripts is made even greater because the second exon can be spliced from three alternative splice sites. Moreover, transcripts initiated at exon VI can sometimes include an additional exon (exon VII). Finally, two alternative polyadenylation sites can be utilized within the 3′ UTR. Thus the bdnf gene can produce a large number of bdnf mRNAs that differ only in their 5′ and 3′ UTRs. The regulatory elements that are critical for calcium-dependent transcription from bdnf promoter IV are shown along with the protein complexes known to assemble at this specific promoter.

CaREs 1–3

Studies of the mechanisms that regulate bdnf transcription have focused mostly on promoter IV (initially numbered promoter III), which is highly responsive to calcium influx both in vivo and in vitro. Promoter deletion studies identified a functional CRE in this promoter (also termed CaRE3) that binds CREB (Shieh et al. 1998, Tao et al. 1998). Expression of dominant-negative CREB mutants disrupts transcriptional activation driven by this promoter. However, bdnf mRNA induction occurs with a slower time course than that of several other CREB target genes, as the peak of bdnf transcriptional activation occurs at least one hour after stimulation (compared to a peak within minutes for both c-fos activation and CREB serine-133 phosphorylation; Tao et al. 1998). Moreover, although both calcium influx and elevated levels of cAMP induce CREB serine-133 phosphorylation and activation, bdnf promoter IV is activated only by calcium influx (Tao et al. 2002). Finally, whereas CREB activity can be induced in both primary neurons and PC12 cells, bdnf expression is induced only by calcium influx into neurons (Tao et al. 2002). These features of activity-dependent bdnf transcription suggested that the induction of this gene might involve a novel mechanism.

To clarify the mechanisms underlying calcium-dependent bdnf promoter IV transcription, two additional calcium-responsive elements (CaRE1 and CaRE2) were identified in bdnf promoter IV in close proximity to the CRE. Yeast one–hybrid experiments identified the upstream stimulatory factors (USFs) as the CaRE2 binding proteins (Chen et al. 2003b) and a novel calcium response factor (CaRF) as the CaRE1 binding protein (Tao et al. 2002). CaRF may confer at least part of the calcium-selective and neuronal-specific features of bdnf promoter IV transcription because reporter assays using a CaRE1 reporter gene or Gal4-CaRF together with a Gal4-dependent reporter gene show that CaRE1 responds specifically to calcium influx into neurons.

The methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2)

Although promoter deletion analyses were very useful early on to identify transcriptional activators that control calcium-dependent gene transcription, additional components of the regulatory network that are recruited to promoters by binding to special features of the chromatin, such as modified histone tails or methylated CpGs, were not identified by deletion analysis.To begin to identify additional activity-regulated gene regulators, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was employed using antibodies that recognize specific proteins that were hypothesized to bind the bdnf genomic locus. This method demonstrated that MeCP2 binds to methylated CpGs in bdnf promoter IV (Chen et al. 2003a, Martinowich et al. 2003). Mutations in the Mecp2 gene in humans lead to Rett syndrome, a severe neurological disorder that arises in girls within the first year of life (reviewed in Moretti & Zoghbi 2006). MeCP2 was initially identified as a repressor protein that binds to methylated CpGs. Once bound to DNA, MeCP2 recruits Sin3A, HDACs, and histone methyltransferases to DNA, leading to the formation of condensed chromatin. The prevailing view indicates that when MeCP2 is bound to DNA, the chromatin formed in the vicinity of MeCP2 is irreversibly silenced. However, in response to calcium influx into neurons, MeCP2 becomes phosphorylated at serine-421 with a time course that closely parallels that of bdnf induction (peaking at 30–60 min after membrane depolarization; Zhou et al. 2006). The loss of Mecp2 by genetic deletion leads to an increase in bdnf promoter IV expression in unstimulated cells (Chen et al. 2003a), whereas mutation of serine-421 to alanine partially blocks calcium-induced bdnf promoter IV expression (Zhou et al. 2006). These findings suggest that MeCP2 represses bdnf transcription and that MeCP2 phosphorylation at serine-421 leads to derepression or some other switch in MeCP2 function. Consistent with the features of bdnf promoter IV activation, MeCP2 phosphorylation at serine-421 is highly enriched within the brain and is induced specifically by extracellular stimuli that lead to calcium influx.

Several lines of evidence suggest that MeCP2 serves an important function specifically within the brain. First, the conditional deletion of Mecp2 in the brain alone recapitulates several aspects of Rett Syndrome (Chen et al. 2001). In addition, deficits in synaptic connectivity have recently been reported in Mecp2 mutant mice, including impaired excitatory synaptic transmission and hippocampal LTP and LTD deficits (Dani et al.2005,Moretti et al. 2006, Nelson et al. 2006). The mechanisms underlying these deficits are unclear, though a recent study showed that reintroduction of the Mecp2 gene in immature or mature Mecp2 null animals that already display Rett-like phenotypes can reverse these neurological symptoms as well as the hippocampal LTP deficit (Guy et al. 2007). A separate study showed that MeCP2 overexpression (which serves as a model of Rett syndrome in cases where the disorder is caused by Mecp2 gene duplication) alters dendritic spine morphology in a manner that is dependent on its ability to be phosphorylated at serine-421 (Zhou et al. 2006). Therefore, activity-dependent modifications of MeCP2 may result in alterations in excitatory synaptic transmission, and disruption of this process may ultimately give rise to Rett syndrome.

A recent study addressed the issue of whether the Rett-like phenotypes found in mecp2 knockout mice are due to the deregulation of bdnf in these animals (Chang et al. 2006). BDNF protein levels are actually reduced in the brains of Mecp2 knockout mice. Although this seems to contradict the role of MeCP2 as a repressor of bdnf promoter IV transcription, a decrease in excitatory transmission in these animals may lead to an indirect decrease in BDNF production and secretion. Consistent with this possibility, transgenic expression of BDNF in Mecp2 knockout animals ameliorates several of the Rett-like phenotypes that the Mecp2 knockout mice display. However, the deregulation of yet-to-be-discovered activity-regulated target genes, in addition to bdnf, also likely contributes to Rett syndrome.

Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2)

Another approach that has recently yielded an additional regulator of bdnf and other activity-regulated genes involves the genome-wide identification of transcription factor target genes. MEF2 family members (A–D) regulate the expression of muscle-specific genes, as well as IEGs such as nur77 and c-jun, in diverse cell types (reviewed in McKinsey et al. 2002). However, a genome-wide screen conducted in our laboratory has also identified as MEF2 targets many neuronal activity-regulated genes, including arc, homer1a, and bdnf (Flavell et al. 2006; S.W. Flavell and M.E. Greenberg, unpublished observations). In the case of bdnf, MEF2 functions in an unusual manner, regulating the expression of each of the promoters so far tested at the bdnf genomic locus (i.e., promoter I, II, III, IV, etc.). These results are supported by the fact that changes in the levels of the mRNAs produced by each of these promoters can be detected as a result of MEF2 loss-and gain-of-function. Moreover, genome-wide mapping of MEF2D binding sites shows that there are several distinct sites of MEF2 binding at the bdnf gene locus.

MEF2 family transcription factors are activated by signaling pathways distinct from those that activate CREB. Class II HDACs, which act as corepressors by antagonizing HAT function, bind to MEF2 prior to membrane depolarization. Upon membrane depolarization and calcium influx, these HDACs are phosphorylated by CaMKs and exported from the nucleus, relieving MEF2 repression and allowing for the activation of MEF2-dependent transcription (Chawla et al. 2003, McKinsey et al. 2002). In addition to this mechanism of calcium-dependent MEF2 activation, calcium influx also leads to the calcium-dependent dephosphorylation (in contrast with CREB phosphorylation) of MEF2 proteins at several different serine residues, an effect that requires the calcium/calmodulin-regulated phosphatase calcineurin (Flavell et al. 2006, Shalizi et al. 2006).Although we do not know yet how MEF2 dephosphorylation leads to activation, inhibition of calcineurin activity prevents calcium-dependent MEF2 activation in neurons.

Reducing the expression of MEF2 in hippocampal neurons causes an increase in the number of excitatory synapses formed onto neurons, suggesting that activation of this factor restricts synapse number (Flavell et al. 2006) Some MEF2 target genes may actively disas-semble excitatory synapses formed onto MEF2-expressing neurons because acute transcriptional activation of MEF2 causes a decrease in synapse number. On the basis of their known functions, Arc and Homer1a are MEF2 targets that might mediate this effect. Arc induction by MEF2 could lead to AMPA receptor internalization, whereas Homer1a induction might lead to the deconstruction of scaffolding complexes at the synapse.

Although bdnf is also a target of MEF2 in neurons that are forming synapses, it is still unclear how BDNF mediates the MEF2-dependent restriction of synapse number. Because BDNF has been studied primarily in the context of synapse maturation, the finding that BDNF is a target of MEF2 might at first seem somewhat contradictory. However, as discussed above, more recent studies have shown that BDNF has diverse functions depending on its posttranscriptional processing and localization, as well as the receptor that it binds. Because MEF2 also regulates several activity-regulated genes whose products control BDNF cleavage from the proBDNF form to the mBDNF form (S.W. Flavell & M.E. Greenberg, unpublished observations), the MEF2 pathway might favor the production of proBDNF under certain circumstances, and under these conditions, proBDNF might contribute to the restriction of synapse number. Alternatively, BDNF and possibly some other MEF2 targets may be selectively deployed to a subset of synapses that will ultimately be retained rather than eliminated.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

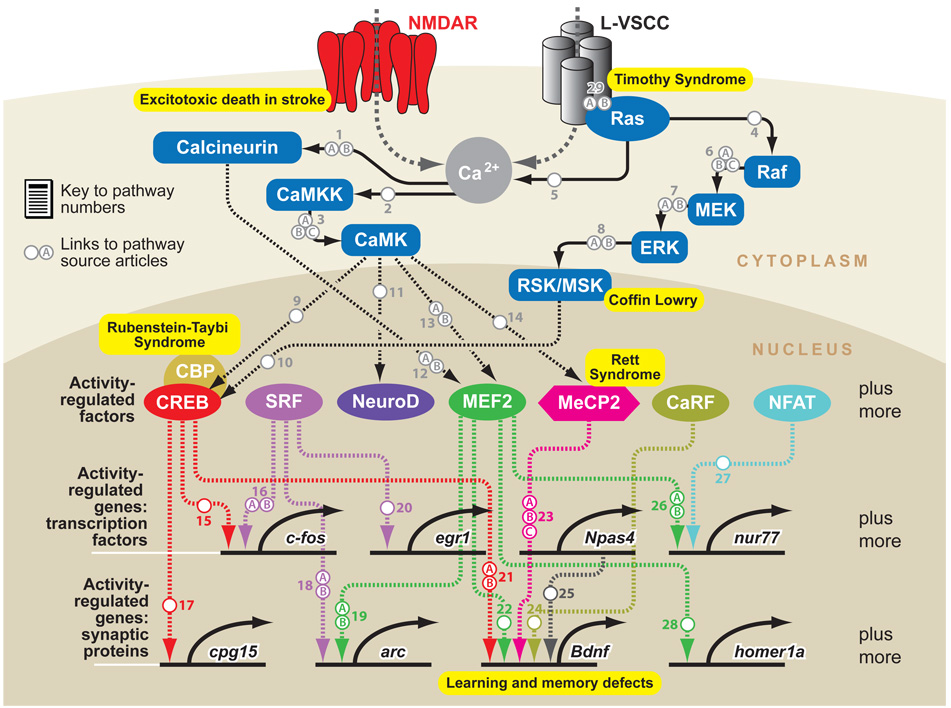

Studies of individual genes, as well as genomic approaches, have characterized an activity-regulated transcriptional program in CNS neurons that consists of hundreds of genes (Figure 3). These genes encode transcriptional regulators as well as proteins that function in dendrites and at synapses. The detailed examination of the biological functions of select genes has revealed that this transcriptional program is critical for neural circuit development and activity-dependent changes in the neural connectivity of adult organisms. Each of these genes contributes to dendritic and synaptic remodeling in a unique way. Whereas some activity-regulated genes encode secreted factors that act as retrograde signals to the presynaptic cell (e.g., bdnf ), others encode truncated, dominant-interfering forms of full-length proteins that function at the synapse (e.g., homer1a). Moreover, through the synaptic localization of activity-regulated mRNAs (e.g., arc) or through the activity-dependent transcription of miRNAs, which locally control mRNA translation (e.g., miR-134), this activity-regulated gene expression program may alter the function of specific synapses formed onto a neuron.

Figure 3.

Signal transduction networks mediating neuronal activity-dependent gene expression. Calcium influx through either neurotransmitter receptors or voltage-gated calcium channels leads to the activation of many calcium-regulated signaling enzymes, which sets in motion several signal transduction cascades. These pathways converge on preexisting transcription factors in the nucleus and lead to their activation through direct posttranslational protein modifications. Several of the activity-regulated genes encode transcriptional regulators, which in turn promote the transcription of additional activity-regulated genes. Many other activity-regulated genes encode proteins that function in dendrites or at synapses and thereby coordinate activity-dependent dendritic and synaptic remodeling within the neuron. Genetic mutations in the genes that encode several of these signaling molecules give rise to neurological disorders in humans ( yellow boxes). Only a subset of the signaling pathways that mediate activity-dependent transcription are shown here.

Because this gene expression program is important for brain development, the signaling mechanisms that link calcium influx to transcription have been extensively investigated. These studies have elucidated many of the mechanisms underlying activity-dependent transcription and have identified many of the transcription factors that coordinate the expression of activity-regulated genes. Investigation of each of these factors reveals that they too have quite specific functions. Whereas CREB is critical for dendritic outgrowth and synaptic potentiation, MEF2 plays a role in restricting excess synapses from forming onto a single neuron. Thus, each of these factors coordinates the expression of a group of target genes that likely act together to accomplish specific aspects of neural circuit development. In the future, the genome-wide definition of each of these subsets of the activity-regulated gene expression program will reveal important information regarding how these processes are controlled by activity.

Human genetic studies have revealed that the disruption of the activity-regulated gene expression program in humans gives rise to neurological disorders. Mutations in key regulators of this gene expression program have been identified as causing or conferring susceptibility to different types of mental retardation and autism-spectrum disorders. These mutations can be found in genes encoding the channels that mediate calcium influx in response to membrane depolarization [the l-VGCC subunit Ca(V)1.2 is disrupted in Timothy syndrome; Splawski et al. 2004], the calcium-regulated signaling enzymes that signal to the nucleus (the gene encoding the CREB serine-133 kinase Rsk2 is mutated in Coffin-Lowry syndrome; Hanauer & Young 2002), the tran-scriptional regulators that mediate gene induction (cbp mutations cause Rubenstein-Taybi syndrome and mecp2 mutations lead to Rett syndrome; Moretti & Zoghbi 2006, Petrij et al. 1995), and the activity-regulated genes themselves (a polymorphism in the bdnf gene confers susceptibility to memory deficits; Bath & Lee 2006). Future studies of this gene expression program will therefore not only provide insight into the mechanisms by which neuronal activity controls neural circuit development and function, but might also reveal how the disruption of activity-dependent brain development gives rise to severe neurological disorders in humans.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Studies examining the functions of neuronal activity-regulated genes provide compelling evidence for the involvement of this activity-regulated transcriptional program in dendritic outgrowth, synaptic maturation/strengthening, synapse elimination, and synaptic plasticity in adult organisms.

Genome-wide analyses have revealed that several hundred activity-regulated genes can be detected in neurons. The functions of only a few of these genes are well described. Owing to the technical limitations of these genomic experiments, many additional activity-regulated genes likely remain to be discovered.

Not all neuronal activity-regulated genes are alike. They are activated with distinct kinetics (fast response vs. slow response) and different stimulus specificity (growth factor– and calcium-responsive vs. calcium-specific) and are often expressed in different cell types (ubiquitous expression vs. brain specific).

Studies of c-fos, bdnf, and other model genes have revealed several molecular mechanisms by which calcium influx can lead to new gene transcription in neurons. Mechanisms for activity-dependent transcription commonly involve the calcium-dependent modification of a transcription factor, increasing its transcriptional activity.

Elucidation of the mechanisms controlling activity-dependent transcription has identified several transcription factors that coordinate the expression of the neuronal activity-regulated genes. Because each factor acts through a distinct cis-acting regulatory sequence, each of these proteins regulates a distinct (but overlapping) set of target genes. Functional experiments have uncovered important roles for many of these factors in dendritic and synaptic remodeling.

Identifying the signaling pathways that mediate calcium-dependent transcription in neurons has also revealed that several of these genes are commonly disrupted by mutations in the human population. These mutations cause or confer susceptibility to neurological disorders, such as mental retardation and autism-spectrum disorders.

FUTURE ISSUES TO BE RESOLVED.

Genome-wide approaches have detected hundreds of activity-regulated genes in neurons. These numbers are likely to be underestimates because they do not include the analysis of noncoding RNAs (such as miRNAs) and are not optimized to detect activity-regulated changes in splicing, polyadenlyation, etc. The complete definition of the activity-regulated gene expression program is therefore incomplete, though this should now be possible through more recent advances in genomic technologies. It also remains unknown which of these genes are targets of which activity-regulated transcription factor.

It is now clear that several activity-regulated transcription factors bind to unique cis-acting regulatory elements. Each of these transcription factors is activated through a distinct signaling mechanism; in some cases, an individual factor can be activated through more than one mechanism. However, it remains unclear which patterns of endogenous neuronal activity favor the activation of which transcription factors (e.g., CREB vs. MEF2) and which mechanisms of activation are utilized in these different physiological contexts (e.g., serine-133 vs. serine-142 CREB phosphorylation).

How this gene expression program coordinates complicated developmental processes such as dendritic branching and the strengthening/elimination of specific synaptic inputs is still unknown. Each of these processes occurs concurrently in a given neuron while the activity-regulated gene expression program is being dynamically activated. Which target genes are utilized for which aspects of development and how these processes are coordinated within the cell are complex problems that remain to be understood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Greenberg lab for critical reading of the manuscript and J. Zieg for help with figures. Our apologies to authors whose work could not be cited or discussed here because of space limitations. Work on this subject in our laboratory is supported by the F.M. Kirby Foundation, as well as Mental Retardation Developmental Disabilities Research Center grant HD18655 and NIH grant NS048276.

Abbreviations

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)

ionotropic glutamate receptors that regulate gene expression and synaptic plasticity by mediating glutamate-and depolarization-dependent calcium influx

- α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor (AMPAR)

ionotropic glutamate receptors that mediate fast synaptic transmission their trafficking to the postsynaptic membrane is tightly controlled during development/plasticity

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- LTD

long-term depression

- Immediate early gene (IEG)

a gene whose expression is increased rapidly and transiently in a protein synthesis–independent manner in response to extracellular stimuli

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- MicroRNA (miRNA)

small noncoding RNAs (∼19–24 base pairs in length) that control the translation or degradation of target mRNAs

- Proximal promoter

the sequence immediately surrounding the transcriptional start site of a gene commonly contains the primary regulatory elements that control gene expression

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CaRE

calcium response element

- CRE

cAMP response element

- CREB

CRE binding protein

- CBP

CREB binding protein

- SRF

serum response factor

- MeCP2

methyl CpG binding protein 2

- MEF2

myocyte enhancer factor 2

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any biases that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:525–535. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H, Hu SC, Bobb K, Balakrishnan K, Ince G, et al. Dendrite development regulated by CREST, a calcium-regulated transcriptional activator. Science. 2004;303:197–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1089845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, Laeng P, Jurata LW, Brockman JA, Lemire A, et al. Electroconvulsive seizures regulate gene expression of distinct neurotrophic signaling pathways. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2667–2677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5377-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A, Stryker MP. Development of individual geniculocortical arbors in cat striate cortex and effects of binocular impulse blockade. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:3549–3573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03549.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CH, Chen M. Morphological basis of long-term habituation and sensitization in Aplysia. Science. 1983;220:91–93. doi: 10.1126/science.6828885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balschun D, Wolfer DP, Gass P, Mantamadiotis T, Welzl H, et al. Does cAMP response element-binding protein have a pivotal role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity and hippocampus-dependent memory? J. Neurosci. 2003;23:6304–6314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06304.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barco A, Alarcon JM, Kandel ER. Expression of constitutively active CREB protein facilitates the late phase of long-term potentiation by enhancing synaptic capture. Cell. 2002;108:689–703. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP, Sheng M, Lau LF, Greenberg ME. Growth factors and membrane depolarization activate distinct programs of early response gene expression: dissociation of fos and jun induction. Genes Dev. 1989;3:304–313. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath KG, Lee FS. Variant BDNF (Val66Met) impact on brain structure and function. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2006;6:79–85. doi: 10.3758/cabn.6.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottai D, Guzowski JF, Schwarz MK, Kang SH, Xiao B, et al. Synaptic activity-induced conversion of intronic to exonic sequence in Homer 1 immediate early gene expression. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:167–175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00167.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]