Abstract

The effect of increased light intensity and heat stress on heat shock protein Hsp60 was examined in two coral species using a branched coral and a laminar coral, selected for their different resistance to environmental perturbation. Transient Hsp60 induction was observed in the laminar coral following either light or thermal stress. Sustained induction was observed when these stresses were combined. The branched coral exhibited comparatively weak transient Hsp60 induction after heat stress and no detectable induction following light stress, consistent with its susceptibility to bleaching in native environments compared to the laminar coral. Our observations also demonstrate that increased light intensity and heat stress exhibited a greater negative impact on the photosynthetic capacity of environmentally sensitive branched coral than the more resistant laminar coral. This supports a correlation between stress induction of Hsp60 and (a) ability to counter perturbation of photosynthetic capacity by light and heat stress and (b) resistance to environmentally induced coral bleaching.

Keywords: Heat shock protein, Hsp60, Light stress, Heat stress, Coral species

Introduction

Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and valuable marine ecosystems on earth (Costanza et al. 1997). Coral bleaching, which results in massive death of coral beds, is currently a major international concern. This phenomenon can be triggered by a range of environmental conditions (Brown 1997). Among the different causes of coral bleaching, thermal stress from global warming and the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is thought to be a likely major contributor to coral damage (Brown 1997; Stone et al. 1999; Bruno et al. 2001). The most widespread coral bleaching incidence has been associated with thermal stress of corals by ENSO that resulted in an increase in seawater temperature over a broad geographic area (McPhaden 1999; Saxby et al. 2003).

In response to environmental stresses, organisms induce heat shock proteins (Hsps) that play important roles in cellular repair and protective mechanisms (Arya et al. 2007; Lanneau et al. 2008). Hsps are crucial in facilitating proper protein folding and complex assembly (Bukau and Horwich 1998). They prevent protein aggregation and regulate stress-induced apoptosis. Sublethal stress, sufficient to induce Hsps, causes cells to acquire cytoprotection that enables them to survive stressful conditions that are normally lethal (Kregel 2002).

In the present investigation, we examine Hsp60 in corals, selecting for study two species that exhibit marked differences in their ability to survive stressful environmental conditions, namely the sensitive branched coral Stylophora pistillata and the more resistant laminar coral Turbinaria reniformis (Riegl and Velimirov 1991; Loya et al. 2001). Investigations of Hsps in most organisms have not examined increased light intensity as a stressful stimulus, whereas there have been frequent studies on the effect of temperature elevation. However, bright light has been shown to be a damaging agent in the rat retina, and prior whole body hyperthermia and intravitreal injection of Hsp70 confer protection against light damage of the retina (Barbe et al. 1988; Yu et al. 2001). The observation that light intensity affects the health of coral beds (Hoegh-Guldberg and Smith 1989; Lesser and Farrell 2004) and a recent report demonstrating the effect of light on heat shock protein Hsp60 homologs in cyanobacteria (Kojima and Nakamoto 2007) influenced the design of our present coral investigation that focuses on Hsp60 and includes, as stressful conditions, both light stress and elevation of water temperature.

Materials and methods

Collection and maintenance of corals

S. pistillata (Sty, a branched coral) and T. reniformis (Tur, a laminar coral), collected from the Red Sea, were maintained under laboratory culture conditions. Nubbins (coral tips, n = 48 for each species) were cultured for 3 weeks prior to experimentation. Salinity and pH of sea water in aquarium tanks were kept constant. Normal temperature was set at 27°C (precision ±0.1°C), logged at 10-min intervals using a Seamon temperature recorder. Halide lamps (400 W, Philips, HPIT) provided a photosynthetically active radiation irradiance (Ferrier-Pagès et al. 2007) of 200 ± 20 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (photoperiod 12:12 h), measured using a 4π quantum sensor (Li-Cor, LI-193SA).

Heat and light stress of corals

Nubbins were subjected to the following conditions: (a) control (27°C, low light [LL; 200 μmol photon m−2 s−1]), (b) high light (HL; 27°C, high light [400 μmol photon m−2 s−1]), (c) heat shock (HS) at 32°C under LL, and (d) HS under HL. Three nubbins of each species were then collected after 24 and 48 h, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Photosynthetic efficiency measurement

Maximal quantum yield (dark adapted Fv/Fm), a parameter for photosynthetic efficiency, was measured at each condition on six nubbins using a DIVING PAM (Walz, Germany) as previously described (Ferrier-Pagès et al. 2007) after either 24 or 48 h of stress treatment. Initial fluorescence (F0) was measured by applying a weak pulsed red light (LED 650 nm, 0.6 kHz, 3 μs). A saturating pulse of bright actinic light (8,000 μmol photons m−2 s−1, width 800 ms) was then applied to give the maximal fluorescence value (Fm). Variable fluorescence (Fv) was calculated as Fm − F0 and maximal quantum yield as Fv/Fm.

Coral sample preparation

Nubbins were reduced to a powder by grinding under liquid nitrogen, weighed, and proteins extracted in 20 μl/g of cold buffer containing 500 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.8), 10% l-ascorbic acid, 20 mM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride, and 10 mg/ml protease inhibitor cocktail. Skeleton fragments were removed by centrifugation on a nylon mesh (1,000×g, 10 min, 4°C) and extracted proteins were freeze-dried.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis

Samples were solubilized in Laemmli buffer and boiled for 20 min, before centrifugation for 15 s at 13,000 rpm to remove insoluble particles. Lowry assay was performed for protein concentration quantification (Peterson 1977). Equal loadings of 50 μg of protein per lane were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using the Mini-PROTEAN 3 Electrophoresis Module Assembly (Bio-Rad) with a stacking gel of 4%, using the standard buffer system of Laemmli, before transferring to nitrocellulose membranes. Antibody specific for Hsp60 (SPA-807) was obtained from StressGen Biotechnologies (BC, Canada). Western blots representative of three experimental repeats are shown. Results were substantiated using a second Hsp60 antibody (SPA-805, StressGen). Optical densities representations of bands were determined by Alpha Innotech FluorChem imaging software. Equal protein loading in each lane was confirmed by Ponceau S staining of Western blots (data not shown).

Sequence and structural analysis of HSP60/GroEL sequences

Protein structure and sequence of GroEL were obtained from Protein Data Bank (PDB id: 1GRU). Viewed by PyMol (http://www.pymol.org), the apical, hinge, and equatorial domains were color annotated on the protein sequence. Hsp60 amino acid sequences for human, sea anemone, and plant (Arabidopsis thaliana) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, with sequence ids P10809, AAR88509, and NP_189041, respectively. They were aligned against GroEL sequence, using ClustalW multiple sequence alignment (http://align.genome.jp/).

Statistical analysis

Comparison of Fv/Fm between treatments was tested using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results

Induction of Hsp60 in two coral species by light and thermal stresses

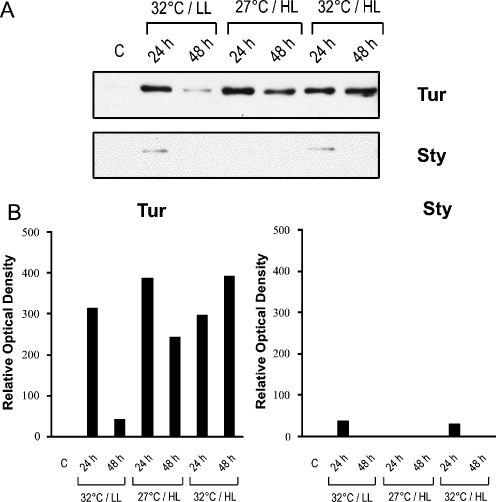

The branched coral (Sty) and the laminar coral (Tur) were subjected either to heat stress (32°C), light stress (HL), or combined heat and light stresses (32°C, HL). Hsp60 expression under these stress paradigms was compared to control conditions (C; 27°C and LL) by Western blotting. A single specific 60-kDa band was detected in the stressed coral samples (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Effect of light and thermal stresses on induction of heat shock protein Hsp60 in the laminar coral T. reniformis (Tur) and the branched coral S. pistillata (Sty). a Immunoblotting demonstrated a robust transient induction of Hsp60 in Tur at 24 h in response to heat stress (32°C) or high light conditions (HL; 400 μE). A more sustained Hsp60 induction at 48 h was observed after heat stress in the presence of high light. Sty exhibited a slight transient induction of Hsp60 at 24 h in response to heat stress but not after increased light intensity. Hsp60 signal was not detected at control conditions (C; 27°C and low light [LL; 200 μE]). b Relative optical density of the Western blot

Transient induction of Hsp60 was detected in the laminar coral (Tur) after temperature elevation from 27°C to 32°C, with a robust expression observed at 24 h followed by a decrease at 48 h (Fig. 1). Transient Hsp60 induction was also observed after an increase in light intensity alone. In contrast to the transient nature of induction triggered by a single stress, the combination of heat and light stresses induced a sustained expression of Hsp60 at 48 h in Tur. A very different response was observed for the branched coral (Sty). A weak Hsp60 induction was noted in Sty at 24 h after temperature elevation, but no detectable induction was apparent after light stress (Fig. 1). Following the combined stress of heat plus light, a weak signal was detected in Sty at 24 h but not at 48 h. These observations were substantiated using a second antibody specific for Hsp60 (SPA-805 from StressGen as listed in “Materials and methods”; data not shown). The two coral species were specifically selected because they exhibit marked differences in their ability to survive stressful conditions in the natural environment, with the laminar coral (Tur) being more resistant to environmental perturbations than the branched coral (Sty; Riegl and Velimirov 1991; Loya et al. 2001).

Effect of light and heat stress on photosynthetic activity of the two coral species

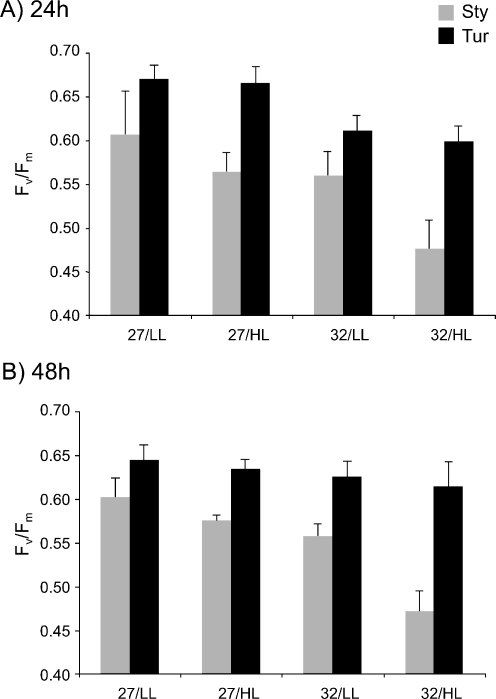

In their natural environment, coral species must engage in photosynthetic activity to survive. Light stress and heat stress decreased photosynthetic efficiency in Sty at 24 h (Fig. 2a), and these effects were still apparent at 48 h (Fig. 2b). Combination of both stresses enhanced the negative impact on photosynthetic activity (Fig. 2b; significance values indicated in Table 1). Heat stress, but not light stress, decreased photosynthetic efficiency at 24 h in Tur (Fig. 2a; Table 1). However, by 48 h, Tur had recovered and exhibited control values of photosynthetic activity, whereas Sty did not show recovery (Fig. 2b; Table 1). Hence, the laminar coral (Tur) that has been reported to better tolerate adverse conditions in the natural environment compared to the branched coral (Sty), demonstrated an enhanced ability to induce Hsp60 in response to light and heat stress, and its photosynthetic apparatus demonstrated the ability to withstand these stressful conditions more effectively.

Fig. 2.

Effect of light and heat stresses on coral photosynthetic activity. Photosynthetic efficiency of the branched coral (Sty) and the laminar coral (Tur) were measured after 24 (a) and 48 h (b) at 27°C or 32°C under low (LL) or high (HL) light intensity. Means and standard deviations of six nubbins are shown

Table 1.

Two-way ANOVA testing the effect of light and heat stresses on maximal photosynthetic efficiency of six nubbins of the branched coral (Sty) and the laminar coral (Tur) after 24 and 48 h of incubation

| After 24 h | After 48 h | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | |

| Sty | ||||

| Heat | 15.95 | 0.002 | 75.50 | <0.001 |

| Light | 13.67 | 0.003 | 43.19 | <0.001 |

| Heat + light | 1.32 | 0.270 | 12.34 | 0.004 |

| Tur | ||||

| Heat | 15.81 | 0.002 | 3.93 | 0.071 |

| Light | 0.34 | 0.568 | 1.11 | 0.312 |

| Heat + light | 0.07 | 0.795 | 1.34 | 0.365 |

Significant values are in bold

Sequence analysis of Hsp60

Comparative amino acid sequence analysis was performed to gain insights into features of Hsp60. GroEL, the Hsp60 bacterial homolog, has been the focus of extensive structural and functional studies compared to Hsp60 in other species (Feltham and Gierasch 2000; Ellis 2006). Amino acid sequence information for sea anemone, a closely related Cnidarian sessile marine animal, was employed since coral Hsp60 sequences are lacking in the literature.

The eight amino acids involved in polypeptide binding

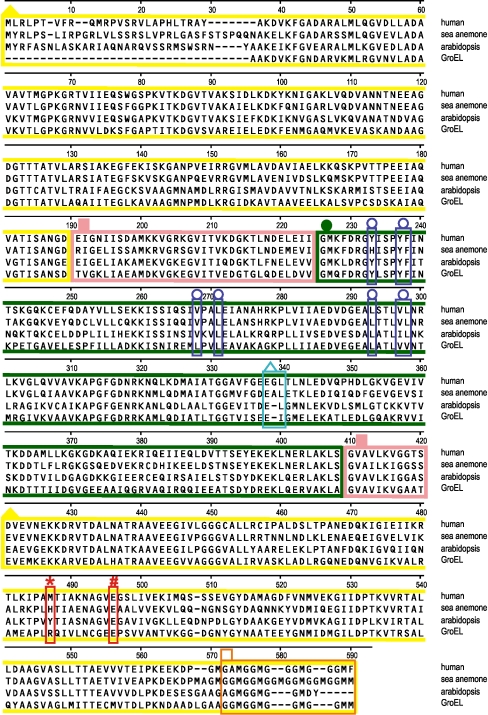

GroEL has two heptameric rings that are stacked back to back (Sigler et al. 1998). The interior wall of the cavity created by the GroEL complex displays hydrophobic amino acids, some of which interact with exposed hydrophobic patches of partially folded polypeptides (Sigler et al. 1998). GroEL mutagenesis has revealed eight hydrophobic amino acids required for polypeptide binding (Fenton et al. 1994). Hsp60 multiple sequence alignment for human, sea anemone, plant (Arabidopsis), and GroEL showed that seven of the eight aforementioned amino acids are either identical or similar in the four species compared (Fig. 3, blue boxes with open circle, alignment position 233 to 298). The exception is sea anemone, where Tyr is replaced by His at alignment position 233.

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of Hsp60/GroEL. Corresponding sequences are shown for Hsp60 of sea anemone, human, plant (Arabidopsis), and bacterial GroEL. The represented color-coded annotation is based on GroEL protein structure (PDB id: 1GRU). The three major domains of GroEL are the equatorial domain (yellow boxes with solid triangle, alignment positions 1–189 and 421–590), the hinge domain (pink boxes with solid squares, alignment positions 190–224 and 410–420), and the apical domain (dark green box with solid circle, alignment positions 226–408). The two red boxes correspond to GroEL amino acids R452 (asterisk, alignment position 487) and E461 (number sign, alignment position 496) that take part in salt-bridge formation, which stabilizes the double-ring structure in GroEL. The six blue boxes (open circle, within alignment position 233 to 298) represent the eight hydrophobic amino acids that are required for the binding of the unfolded polypeptide to the interior wall of the cavity created by the GroEL–GroES complex. The insertion of a small amino acid at alignment position 339 is shown using a cyan box (open triangle, alignment positions 338–340; Gly insertion in human, Ala insertion in sea anemone). The Gly-Gly-Met repeats at the C-terminal of Hsp60 are shown in an orange box (open square, alignment positions 572–590)

The salt-bridge

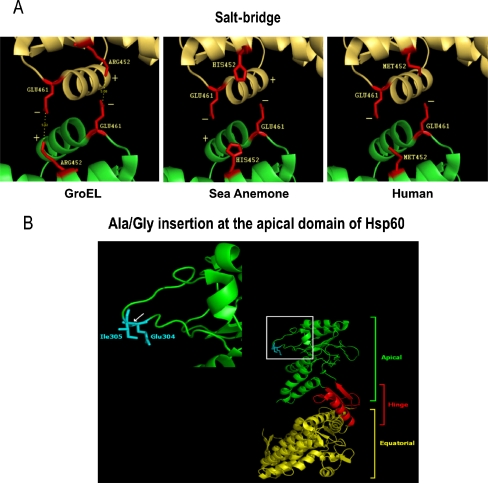

R452-E461 salt-bridge formation (Fig. 4a, GroEL) allows GroEL to exist as a double heptameric ring (Brocchieri and Karlin 2000). The salt-bridge forming Arg (GroEL amino acid R452) is replaced by Tyr in plant (Arabidopsis), Met in human, and His in sea anemone (Fig. 3, red box with asterisk, alignment position 487). Models for the equivalent GroEL R452-E461 salt bridge in sea anemone and human Hsp60 are shown in Fig. 4a. In human Hsp60, substitution of Arg by Met disrupts salt-bridge formation (Fig. 4a, human), resulting in a single ring structure (Viitanen et al. 1992; Levy-Rimler et al. 2002). Substitution of His in sea anemone (Fig. 4a, sea anemone) could enable adoption of either a single- or double-ring structure depending on environmental conditions (Choresh et al. 2004). At low pH, His acquires a net positive charge allowing sea anemone Hsp60 to mimic the GroEL double-ring structure; at high pH, basic groups of His remain uncharged and sea anemone Hsp60 could behave as its single-ringed human homolog.

Fig. 4.

a Salt bridges—GroEL, sea anemone Hsp60, and human Hsp60. Equatorial domain of upper subunit is shown in yellow and lower subunit in fluorescent green. The GroEL amino acids R452 and E461 which participate in the salt-bridge formation are shown in red, connected by dotted lines (GroEL). b Ala/Gly insertion in human and sea anemone Hsp60. A small amino acid (Gly in human, Ala in sea anemone) is inserted at the location indicated by a white arrow that corresponds to the apical domain of GroEL, between Glu (GroEL amino acid E304; signified as GLU304) and Ile (GroEL amino acid I305; signified as ILE305)

Ala/Gly insertion at the apical domain of Hsp60

Compared to plant (Arabidopsis) Hsp60 and GroEL, insertion of an extra amino acid in the apical domain was observed for sea anemone (Ala insertion) and human (Gly insertion; Fig. 3, cyan box with open triangle, alignment positions 338–340). The insertion corresponds to the apical domain of GroEL, between Glu (GroEL amino acid E304) and Ile (GroEL amino acid I305) as indicated by a white arrow (Fig. 4b).

The conserved Gly-Gly-Met motif

A series of conserved Gly-Gly-Met repeats appears at the C-terminal region of Hsp60 sequences (Fig. 3, orange box with open square, alignment positions 572–590). A higher number of Gly-Gly-Met repeats were apparent for sea anemone Hsp60 compared to the other species examined.

Discussion

In response to stressful stimuli, organisms induce Hsps that play major roles in cellular repair and protective mechanisms (Arya et al. 2007; Lanneau et al. 2008). The most widely studied inducer is temperature elevation (Kregel 2002). Other stressors, such as oxygen deprivation, heavy metals, and toxins, can also trigger the induction of Hsps (Morimoto et al. 1997). Light stress is known to adversely affect the health of coral beds (Hoegh-Guldberg and Smith 1989; Lesser and Farrell 2004), and a recent report has demonstrated an effect of light on Hsp60 homologs in cyanobacteria (Kojima and Nakamoto 2007).

The present report investigates the effect of elevation of light intensity and water temperature on Hsp60 synthesis in marine corals. Major differences in Hsp60 inducibility are apparent in the two coral species, selected for their different tolerances to environmental perturbation. The laminar coral demonstrated a robust transient induction of Hsp60 in response to both light and heat stress in contrast to the branched coral. This observation is consistent with the relative susceptibility of branched coral to bleaching triggered by environmental conditions resulting in the massive death of coral beds of this species (Riegl and Velimirov 1991; Loya et al. 2001). Our observations also demonstrate that increased light intensity and heat stress exhibited a greater negative impact on the photosynthetic capacity of environmentally sensitive branched coral than the more resistant laminar coral. Interestingly, an Hsp60 homolog has been proposed to protect photosynthetic apparatus from thermal denaturation through association with Rubisco activase (Salvucci 2008).

These results support a correlation between stress induction of Hsp60 and (a) ability to counter perturbation of photosynthetic capacity by light and heat stress and (b) resistance to environmentally induced coral bleaching. Sublethal light stress encountered at midday periods of peak light intensity could trigger Hsp60 synthesis in the laminar coral and protect it from adverse environmental conditions, whereas lack of Hsp60 induction in the branched coral could render it more sensitive to damage. We suggest that Hsp60 induction levels could be a potential indicator of resistance to stress-induced coral bleaching in diverse coral species. The mechanism of resistance may or may not involve the classical heat shock response and cytoprotection in the form of thermotolerance. Hsp60 could protect the photosynthetic machinery using a different mechanism other than thermotolerance.

Differential susceptibilities of corals to bleaching have been reported in various reefs systems in the world (Riegl and Velimirov 1991; Marshall and Baird 2000). In the Great Barrier Reef, preferential resistance of laminar over branched corals to bleaching was observed (Marshall and Baird 2000). In Red Sea reefs, where our samples were originally acquired, the branched coral (Sty) is one of the most susceptible coral species to tissue lost and damage (Riegl and Velimirov 1991).

Comparative amino acid sequence analysis was performed to gain insights into features of Hsp60. Amino acid sequence information was employed for sea anemone, a closely related sessile marine animal, since coral Hsp60 sequences are lacking in the literature. Both organisms are classified as Cnidarians. We identified interesting features of Cnidarian Hsp60 by comparing amino acid sequence of Hsp60 homologs. The Ala amino acid insertion in the apical domain of sea anemone Hsp60 is particularly interesting. As the apical domain is involved in polypeptide binding, it is possible that Cnidarian and human Hsp60 may have different protein substrate specificity when compared to other Hsp60 homologs. The higher number of C-terminal Gly-Gly-Met repeats observed for sea anemone Hsp60 is intriguing. The structure and function of this motif is not fully elucidated (Gupta 1995; Sanchez et al. 1999); however, it could potentially alter the internal cavity of the GroEL heptameric ring at the level of the equatorial domain (Saibil et al. 1993; Thiyagarajan et al. 1996). We also note the replacement of a conserved Tyr by His in one of the eight essential hydrophobic amino acids involved in polypeptide binding in sea anemone Hsp60. Although the physiological significance and potential benefits of these sequence variations in Cnidarian Hsp60 are not fully understood, changes in these critical domains could potentially affect the regulation and hence kinetics of Hsp60-mediated protein folding in corals.

The two GroEL heptameric rings are attached through contacts including a salt-bridge between Arg (GroEL amino acid R452) and Glu (GroEL amino acid E461; Sigler et al. 1998; Brocchieri and Karlin 2000). In sea anemone, substitution of this salt-bridge forming Arg (GroEL amino acid R452) by His could potentially cause Hsp60 to exist as either a single or double ring. As salt bridges may function to ensure inter-ring communication at contact sites for functional chaperone cycles and allow GroEL to act as a thermostat to distinguish physiological temperatures from heat stress (Sot et al. 2002), the ability to switch between single-/double-ring structure may enhance the ability of Cnidarian Hsp60 to mediate protein folding.

Hsp60 in sessile Cnidarian marine animals may exhibit adaptability to changing environmental conditions. GroEL mutational analysis has demonstrated that different protein substrates exhibit a preference for the single- or double-ring structure (van Duijn et al. 2007). Single-/double-ring interchangeability in sea anemone, a Cnidarian closely related to corals, could enable Hsp60 to cater for specific sets of binding substrates that may require protein conformational adjustments following stressful environmental conditions.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from (a) NSERC Canada to I.R.B. who also holds a Canada Research Chair and (b) Centre Scientifique de Monaco to C.F.-P. We thank Cecile Rottier for maintenance of corals and Erin Chang for assistance with Western blots.

References

- Arya R, Mallik M, Lakhotia SC. Heat shock genes—integrating cell survival and death. J Biosci. 2007;32:595–610. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbe MF, Tytell M, Gower DJ, Welch WJ. Hyperthermia protects against light damage in the rat retina. Science. 1988;241:1817–1820. doi: 10.1126/science.3175623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocchieri L, Karlin S. Conservation among HSP60 sequences in relation to structure, function, and evolution. Protein Sci. 2000;9:476–486. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.3.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BE. Coral bleaching: causes and consequences. Coral Reefs. 1997;16:S129–S138. doi: 10.1007/s003380050249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno JF, Siddon CE, Witman JD, Colin PL, Toscano MA. El Nino related coral bleaching in Palau, Western Caroline Islands. Coral Reefs. 2001;20:127–136. doi: 10.1007/s003380100151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choresh O, Loya Y, Muller WE, Wiedenmann J, Azem A. The mitochondrial 60-kDa heat shock protein in marine invertebrates: biochemical purification and molecular characterization. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:38–48. doi: 10.1379/469.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R, dArge R, deGroot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, ONeill RV, Paruelo J, Raskin RG, Sutton P, vandenBelt M. The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 1997;387:253–260. doi: 10.1038/387253a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ. Protein folding: inside the cage. Nature. 2006;442:360–362. doi: 10.1038/442360a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltham JL, Gierasch LM. GroEL-substrate interactions: molding the fold, or folding the mold? Cell. 2000;100:193–196. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton WA, Kashi Y, Furtak K, Horwich AL. Residues in chaperonin GroEL required for polypeptide binding and release. Nature. 1994;371:614–619. doi: 10.1038/371614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier-Pagès C, Richard C, Forcioli D, Allemand D, Pichon M, Shick M. Effects of temperature and UV radiation increases on the photosynthetic efficiency in four scleractinian coral species. Biol Bull. 2007;213:76–87. doi: 10.2307/25066620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RS. Evolution of the chaperonin families (Hsp60, Hsp10 and Tcp-1) of proteins and the origin of eukaryotic cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O, Smith GJ. The effect of sudden changes in temperature, light and salinity on the population-density and export of Zooxanthellae from the reef corals Stylophora pistillata Esper and Seriatopora hystrix Dana. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1989;129:279–303. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(89)90109-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K, Nakamoto H. A novel light- and heat-responsive regulation of the groE transcription in the absence of HrcA or CIRCE in cyanobacteria. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1871–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregel KC. Heat shock proteins: modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2177–2186. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanneau D, Brunet M, Frisan E, Solary E, Fontenay M, Garrido C. Heat shock proteins: essential proteins for apoptosis regulation. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:743–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser MP, Farrell JH. Exposure to solar radiation increases damage to both host tissues and algal symbionts of corals during thermal stress. Coral Reefs. 2004;23:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s00338-004-0392-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Rimler G, Bell RE, Ben-Tal N, Azem A. Type I chaperonins: not all are created equal. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loya Y, Sakai K, Yamazato K, Nakano Y, Sambali H, Woesik R. Coral bleaching: the winners and the losers. Ecol Lett. 2001;4:122–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00203.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PA, Baird AH. Bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef: differential susceptibilities among taxa. Coral Reefs. 2000;19:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s003380000086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPhaden MJ. Genesis and evolution of the 1997–98 El Nino. Science. 1999;283:950–954. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5404.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI, Kline MP, Bimston DN, Cotto JJ. The heat-shock response: regulation and function of heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones. Essays Biochem. 1997;32:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson GL. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal Biochem. 1977;83:346–356. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegl B, Velimirov B. How many damaged corals in Red Sea reef systems? A quantitative survey. Hydrobiologia. 1991;216/217:249–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00026471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saibil HR, Zheng D, Roseman AM, Hunter AS, Watson GM, Chen S, Auf Der Mauer A, O'Hara BP, Wood SP, Mann NH, Barnett LK, Ellis RJ. ATP induces large quaternary rearrangements in a cage-like chaperonin structure. Curr Biol. 1993;3:265–273. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90176-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvucci ME. Association of Rubisco activase with chaperonin-60beta: a possible mechanism for protecting photosynthesis during heat stress. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:1923–1933. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez GI, Carucci DJ, Sacci J, Jr., Resau JH, Rogers WO, Kumar N, Hoffman SL. Plasmodium yoelii: cloning and characterization of the gene encoding for the mitochondrial heat shock protein 60. Exp Parasitol. 1999;93:181–190. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxby T, Dennison WC, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Photosynthetic responses of the coral Montipora digitata to cold temperature stress. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2003;248:85–97. doi: 10.3354/meps248085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sigler PB, Xu Z, Rye HS, Burston SG, Fenton WA, Horwich AL. Structure and function in GroEL-mediated protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:581–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sot B, Galan A, Valpuesta JM, Bertrand S, Muga A. Salt bridges at the inter-ring interface regulate the thermostat of GroEL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34024–34029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone L, Huppert A, Rajagopalan B, Bhasin H, Loya Y. Mass coral reef bleaching: a recent outcome of increased El Nino activity? Ecol Lett. 1999;2:325–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.1999.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiyagarajan P, Henderson SJ, Joachimiak A. Solution structures of GroEL and its complex with rhodanese from small-angle neutron scattering. Structure. 1996;4:79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijn E, Heck AJ, Vies SM. Inter-ring communication allows the GroEL chaperonin complex to distinguish between different substrates. Protein Sci. 2007;16:956–965. doi: 10.1110/ps.062713607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viitanen PV, Lorimer GH, Seetharam R, Gupta RS, Oppenheim J, Thomas JO, Cowan NJ. Mammalian mitochondrial chaperonin 60 functions as a single toroidal ring. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:695–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Kent CR, Tytell M. Retinal uptake of intravitreally injected Hsc/Hsp70 and its effect on susceptibility to light damage. Mol Vis. 2001;7:48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]