Abstract

We calculate the statistics of diffusion-limited arrival-time distribution by a Monte Carlo method to suggest a simple statistical resolution of the enduring puzzle of nanobiosensors: a persistent gap between reports of analyte detection at approximately femtomolar concentration and theory suggesting the impossibility of approximately subpicomolar detection at the corresponding incubation time. The incubation time used in the theory is actually the mean incubation time, while experimental conditions suggest that device stability limited the minimum incubation time. The difference in incubation times—both described by characteristic power laws—provides an intuitive explanation of different detection limits anticipated by theory and experiments.

In recent years, reports from various leading research groups1, 2, 3, 4 have suggested the possibility of subfemtomolar detection of biomolecules by nanowire (NW) and nanotube (NT) biosensors. Subsequent theoretical analysis, however, have been only partially valid in interpreting the experimental results and this absence of an experimentally validated theoretical framework have made it difficult to compare results from different laboratories and have frustrated rapid optimization of the technology. In general, theoretical models based on diffusion-limited capture of analyte molecules do suggest that the “geometry of diffusion” makes cylindrical NWs superior to planar field-effect transistor sensors in their ability to respond to low analyte density.5 Given the specific dimension of the sensors used in experimental demonstration of “femtomolar detection” and given reported incubation times of a few minutes, the scaling law suggests a theoretical lower limit of detection of ρs∼1 pM—with no obvious explanation of the gap between theory and experiments.

In this paper, we offer a statistical interpretation to resolve this puzzle (see Fig. 1). The classical models of biosensors5, 6, 7 consider the response of an asymptotically large system (e.g., a NW of infinite length) and as such, the predicted theoretical response time is relevant for practical nanobiosensors only in the sense of an ensemble average, i.e., time when ∼50%, for sensors in a large sensor array registers the presence of the analytical molecule. In practice, the finite size of NW sensors dictates that some element of the ensemble (sensor) would respond before the others, i.e., the response time will be statistically distributed. Given the number of sensors in an array is finite and their lifetime in harsh fluid environment limited2 (see Section B of Ref. 8 for a detailed discussion of the stability-limited response time), the reported response times could actually be the minimum response time of the system—representing the tail of a broad arrival-time distribution. Figure 1 shows that for a given incubation time, the requirement that only one or few sensors respond compared to that of requirement that 50% of the sensors respond could lead to significantly different detection limits for a given technology.

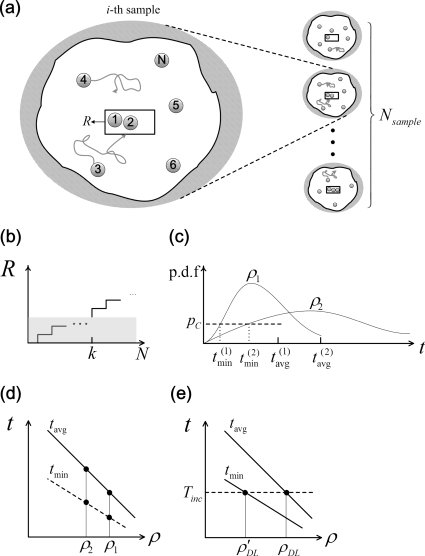

Figure 1.

(a) The generalized model of nanobiosensors: absorbing box inside a domain captures diffusing particles, (b) generates a detection signal once a minimum of k particles has been captured. Robust positive detection is indicated when Nc such sensors (out of a total of Nsample) captures at least k particle each. The shadowed region indicates a noise of the signal. (c) The population distribution of the response times for different molecular densities: ρ1>ρ2. One can correspondingly define their minimum response time (tmin) as being the Ncth-smallest one among those Nsample response times. pc indicates the PDF for t=tmin whose corresponding CDF is Nc∕Nsample. (d) The statistical nature of diffusion process makes the minimum response time (dotted line) significantly different from the ensemble-average time (solid line). (e) For a given incubation time Tinc, the detection limit based on minimum arrival time (ρDL)′ is significantly lower than that based on the classical ensembled average detection limit, ρDL.

Consider a cylindrical NW sensor surrounded by a static analyte solution. The specific receptors for the target molecules are immobilized on the surface of the sensor. In the reaction-diffusion (RD) model,9 the conjugation dynamics of target molecules to their receptors is described by

| (1) |

where Ns is the density of conjugated receptors, N0 is the density of receptors on the sensor surface, and kf and kr are the capture and dissociation constants. The concentration of molecules at the sensor surface at a given time t, ρs(t), is determined by RD model as well as by the diffusion of target molecules set by the concentration gradient at the sensor surface which is given by the diffusion equation

| (2) |

where D is the diffusion coefficient of target molecules in the solution. The classical solution of Eqs. 1, 2 provides “ensembled-averaged” response time of biosensors In the following discussion, we assume that the sensor is described by a perfectly absorbing boundary condition (kf→∞, kr=0). This assumption implies that transport is diffusion limited (Damkohler number>1) and that the biosensor response time at a particular concentration (to be defined below) is shorter than the reaction limited saturation time (i.e.,t<tS[=1∕(kr+kfρ)]). The validity of both these assumptions are confirmed in Sections B and C of Ref. 8.

To calculate distribution of response∕registration times—not simply their ensemble average—one must determine sample-specific response of biosensor at a given analyte density by solving Eqs. 1, 2 stochastically by Monte Carlo (MC) method.10 The direct Monte Carlo solution is computationally intractable—explaining why no such calculation has ever been reported in the literature despite its broad interest and obvious relevance for large class of stochastic biological problems (e.g., Refs. 11, 12, 13). Instead of using a direct Monte Carlo method, we use the following variant of the MC technique—the so-called “table-based MC (TMC) approach”14, 15—to analyze the problem. The basic idea of TMC is to use the MC method to numerically calculate and tabulate the capture time distributions for particles injected at various starting position, i.e., to numerically precalculate and store the Green’s function11 from any random starting point to the sensor surface. For example, the (i,j)th element of the table, Gi,j≡G(ri,tj) describes the probability that a particle injected at location ri at time t=0 is captured by the sensor at time tj=jΔt. For the calculation proper, a sample S is first created by specifying the initial positions of the particles consistent with a specific density of analyte, ρM. For each particle from , its capture time by the sensor is stochastically chosen to be consistent with the precalculated arrival-time distribution from that point, Gi,(.)≡G(ri…). The process is repeated for all M analyte molecules of the sample S to obtain a sorted list of arrival times, ts,m; m=1…M. If k is the number of particles required for an observable sensor response, then ts,m=k is the initial response time for this sensor. The process is repeated for large number of samples (N∼1000 s) to establish an kth arrival-time distribution at a particular density of analytes {ts=1…N;k}. The ensemble average of {ts=1…N;k} coincides with the continuum solution of Eqs. 1, 2, as expected. We have also independently verified that this approach correctly reproduces the analytical results for many-particle capture dynamics for simplified cases of one-dimensional diffusion (see Section E in Ref. 8).

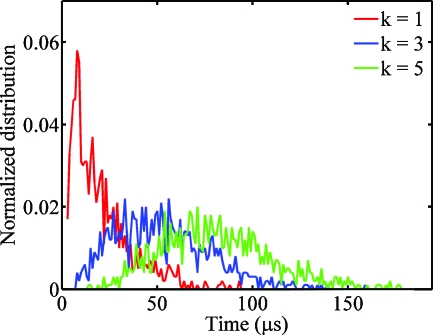

For an illustrative example (see Figs. 23), we consider a NW of radius 50 nm,1 the length 1 μm, diffusion coefficient D∼10−6 cm2∕s (for a summary of various geometrical and physical parameters, see Table I in Ref. 8), simulation lattice size Δx=20 nm and simulation time increment Δt is 1 μs. Figure 2 shows the normalized distributions of the kth arrival times (k=1,3,5) for an ensemble of 2000 NW-based biosensors (N=2000). Specifically, the red line indicates PDF of arrival times for those sensors sensitive enough to register the presence of analyte by the capture of k molecules. Several features of the distribution are obvious. First, for all PDFs, the average arrival time (∼50% of the sensors indicating the presence of analyte) is significantly larger compared to the corresponding minimum arrival time when—for example—5%–10% of the sensors indicate the presence of the analyte, promising a resolution of the “theory-experiment” gap discussed in the introduction. Second, the ratio of tk,min∕tk,avg reduces with k—in other words, the more sensitive the sensor (k∼smaller), the larger is the gap between tk,min and tk,avg. Finally, the minimum of the kth arrival times exhibit different scaling laws from the average arrival time because the statistical probability of k molecules being placed close to the sensors is different from average response that is dictated by distribution of all samples.

Figure 2.

Population distributions of the first (k=1), third (k=3), and fifth (k=5) arrival time for a NW biosensor at a molecular concentration ρ=53 nM. k=1 implies sensors capable of single-molecule detection, while k>1 implies less sensitive sensors that requires multiple analyte capture for positive detection above the noise floor.

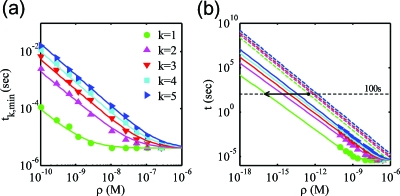

Figure 3.

(a) The scaling relationship of both the minimum and average of the kth arrival time with respect to the molecular concentration for a NW-based biosensor. The distributions of arrival times are obtained by collecting the kth arrival times from 2000 samples of biosensor, i.e., Nsample=2000. Note that NC=20, corresponding to 1% tail of the PDF (see Section D of Ref. 8 for responses for other definitions of the tail of the PDF). (b) From an extrapolated curve of the first arrival time (k=1, solid green curve), the minimum detection limit corresponding to a given incubation time decreases by about three orders of magnitude. Dotted curves indicate the average response times for k=1…5.

Let us now examine the minimum and average of the arrival times among 2000 biosensor requiring at least five molecules to register an output signal (i.e., PDF of tN=2000;k=5 with k=5) and measure the variations of minimum response times with respect to various analyte concentrations. Remarkably, analogous to the scaling law for average response time or equivalently ,5 Fig. 3 suggests the following simple scaling law of the minimum response time for detecting k molecules:

| (3) |

where αk is the power exponent of the minimum time to detect target molecules.

Figure 3a shows that for biosensors with single-molecule sensitivity (k=1), the minimum arrival time increases much more slowly compared to the average response. This difference of response time with ρ0 is easy to understand. As the concentration of analyte molecules is reduced, the average distance of molecules from the sensor increases rapidly and so does the average response time. At subnanomolar concentration, the minimums of the kth arrival times (k≥1) increases with the same-power exponent (∼1) as the average response time since the probability that multiple molecules are populated very next to the sensor surface decrease as rapidly as the average distance of molecules away from the sensor surface. This implies that the ratio of the minimum to the average of the kth arrival times at a low density,

| (4) |

where tk,avg indicates the average response time to detect k target molecules derived from the scaling law. We find that c(k) increases rapidly at the low arrival order but increases slowly at the high arrival order, and eventually it could approach 1 when the arrival order goes to infinity, as expected. The observed value of c(k) from Fig. 3 ∼10−2–10−3 for low values of k(≤3) indicates that the theoretically calculated average arrival time reported in the literature could differ from the experimentally relevant minimum arrival time by a two to three orders of magnitude. Since αk∼1∕MD∼1, the difference in arrival time directly translates into the difference in minimum detection limits. Specifically, in Fig. 3b, we find that the minimum detection limit corresponding to typical incubation time of ∼100 s decreases by more than three orders of magnitude when one compares the minimum and average response time curves for k=1. This provides a simple resolution of the gap between previous theoretical results (approximately picomolar) and experimental demonstrations (approximately femtomolar). Obviously, the gap reduces rapidly at higher density—explaining why such an issue has not been dominant for older classical sensors. In general, Eq. 4 may be used to simply estimate the minimum response time for molecular detection first using the scaling law of the average response time, , and then multiplying the ratio c(k) to the average response time.

Given the difference between minimum and average incubation times and corresponding difference in detection limits, it is important to provide technology-specific context of such limits. For example, for a sensors network widely dispersed in a battlefield to signal the presence of a single bioagent (i.e., nerve gas), the specification of minimum response time is relevant because the registration of the molecules with first few sensors is sufficient to trigger system-wide response. On the other hand, for sensor arrays involving in proteomic and geomonic applications, all the sensors must complete bindings before the experiment is terminated. In this case, the relevant incubation time is much larger than even average response time at that concentration. Therefore, the minimum response time is an irrelevant indicator of promise∕utility of the biosensor technology for such technological applications.

To conclude, we have developed a comprehensive model describing the statistical distributions of response time for an ensemble of cylindrical NW∕NT biosensors. Our numerical studies suggest that the minimum and average response are both characterized by respective power laws, which provide a framework for interpretation of experimental detection at femtomolar concentration, thereby providing an plausible explanation of an important puzzle in the biosensor literature.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pradeep R. Nair for detailed discussions. This work was supported by funds from the Network for Computational Nanotechnology (NCN) and National Institute of Health (NIH).

References

- Hahm J. and Lieber C. M., Nano Lett. 4, 51 (2004). 10.1021/nl034853b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stern E., Klemic J. F., Routenberg D. A., Wyrembak P. N., Turner-Evans D. B., Hamilton A. D., LaVan D. A., Fahmy T. M., and Reed M. A., Nature (London) 445, 519 (2007). 10.1038/nature05498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M., Cuda G., Bunimovich Y. L., Gaspari M., Heath J. R., Hill H. D., Mirkin C. A., Nijdam A. J., Terracciano R., Thundat T., and Ferrari M., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 10, 11 (2006). 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Agarwal A., Trigg A. D., Singh N., Fang C., Tung C., Fan Y., Buddharaju K. D., and Kong J., Anal. Chem. 79, 3291 (2007). 10.1021/ac061808q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P. R. and Alam M. A., Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 233120 (2006). 10.1063/1.2211310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Squires T. M., Messinger R. J., and Manalis S. R., Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 417 (2008). 10.1038/nbt1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan P. E. and Whitman L. J., Nano Lett. 5, 803 (2005). 10.1021/nl050298x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See EPAPS supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3176017 E-APPLAB-95-027928for the detailed discussions validating the present article.

- Avraham D. B. and Havlin S., Diffusion and Reactions in Fractals and Disordered Systems (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Redner S., A Guide to First-Passage Processes (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Condamin S., Benichou O., Tejedor V., Voituriez R., and Klafter J., Nature (London) 450, 77 (2007). 10.1038/nature06201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benichou O. and Voituriez R., Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 168105 (2008). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.168105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuss Z., Singer A., and Holcman D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 16098 (2007). 10.1073/pnas.0706599104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M. A. and Lundstrom M., Appl. Phys. Lett. 67, 512 (1995). 10.1063/1.114553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butt N. Z., Yoder P. D., and Alam M. A., IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 54, 2363 (2007). 10.1109/TNS.2007.910204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]