Abstract

PURPOSE

Effective methods of serial epithelial sampling to measure breast-specific biomarkers will aid the rapid evaluation of new preventive interventions. We report here a proof-of-principle Phase 2 study to assess the utility of ductal lavage (DL) to measure biomarkers of tamoxifen action.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

We enrolled women with a 5-year breast cancer risk estimate >1.6%, or the unaffected breast of women with T1a or T1b breast cancer. After entry DL, participants chose tamoxifen or observation, and underwent repeat DL six months later. Samples were processed for cytology and immunohistochemistry for ERα, Ki-67, and COX-2.

RESULTS

Of 182 women recruited, 115 (63%) underwent entry and repeat DL; 85 (47%) had sufficient cells for analysis from ≥ 1 duct at both time-points; in 78 (43%) were sufficient from ≥ 1 matched ducts. Forty-six women chose observation and 39 chose tamoxifen. We observed greater reductions in the tamoxifen than in the observation groups for Ki-67 (adjusted p=0.03), ERα_(adjusted p=0.07), but not in COX-2 (adjusted p=0.4) labeling Cytologic findings showed a trend towards improvement in the tamoxifen compared to the observation group. Inter-observer variability for cytologic diagnosis between two observers showed good agreement (κ=0.44).

CONCLUSIONS

Using DL, we observed the expected changes in tamoxifen-related biomarkers; however, poor reproducibility of biomarkers in the observation group, the 53% attrition rate of subjects from recruitment to biomarker analyses, and the expense of DL, are significant barriers to the use of this procedure for biomarker assessment over time.

INTRODUCTION

Ductal lavage (DL) is a minimally invasive technique that allows sampling of breast ductal epithelium in healthy high risk women with a significantly better cell yield compared to nipple aspirate fluid 1-3. This allows the possibility of monitoring response to prevention agents by serial sampling of epithelial cells, using biomarkers relevant to the agent being tested. Thus, DL is a potentially attractive tool for assessing effects of chemoprevention agents 1.

To establish the principal that biomarkers of chemoprevention agents can be monitored using DL, we initiated a Phase 2, non-randomized trial using tamoxifen, the gold-standard breast cancer chemoprevention agent 4. We reasoned that the efficacy of tamoxifen in the prevention of estrogen receptor (ER) positive breast cancer has been clearly demonstrated and a study utilizing tamoxifen as the preventive intervention should enable the efficient evaluation of DL as a tool for repeat epithelial sampling in Phase 2 prevention studies. Furthermore, since tamoxifen does not prevent all breast cancer, if markers of tamoxifen efficacy could be identified it may be possible to target therapy to those most likely to benefit from it.

We now report the final results of this trial, having recruited 182 women, of whom 85 were evaluated for biomarker results at two time-points. We present a comparative analysis of women who accepted tamoxifen therapy following baseline DL, and those who declined. In addition, we address an aspect of DL that adds to the complexity and cost of this technique of biomarker monitoring; i.e., whether there is an advantage to analyzing each duct separately or whether averaging duct samples from the same woman provides similar information. We have therefore reported data for individual ducts, as well as for women (an average of all ducts lavaged during a single procedure). We report here our findings on cytology, as well as cell number and other immunohistochemical biomarkers (ERα, Ki-67, and COX-2), for the 39 women in the tamoxifen group and 46 in the observation group.

METHODS

Study Design

Subjects were recruited between March 1, 2003, and March 31, 2006, from the Bluhm Family Program for Breast Cancer Early Detection and Prevention and the Lynn Sage Breast Center at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, IL. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University, and all participants signed a document of informed consent.

Potential subjects completed a questionnaire regarding breast cancer risk factors at their first visit and a 5 year breast cancer risk estimate was calculated using statistical models 5;6. Eligible women aged 35-60 years were at increased risk for breast cancer (5 year risk estimate of >1.6%), or had completed local therapy for unilateral estrogen receptor positive duct carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer <1cm in size and did not require chemotherapy. Baseline DL was performed by one of two operators (SAK or MB). In premenopausal women, the DL procedure was not timed to a specific menstrual phase, but information regarding the last menstrual period and the onset of the next period was recorded. Participants were counseled regarding the cytological findings from the DL samples, and the risks and benefits of tamoxifen therapy, and were allowed to choose tamoxifen therapy or observation. Subjects underwent repeat lavage six months later. As much as possible, follow-up DL in premenopausal women was performed in the same phase of the cycle as the first DL procedure.

Ductal Lavage Procedure

The details of the DL procedure have been described previously 1. Briefly, this involved application of a topical anesthetic cream, warming and massage of the breast, use of an aspirator cup (Cytyc Corp.) to elicit nipple aspirate fluid (NAF), and cannulation of fluid yielding and (when possible) non-fluid yielding ducts using a microcatheter (Cytyc Corp.) and a physiological buffer solution (Plasmalyte; Baxter Healthcare Corporation). The lavage effluent was collected in Cytolyte® (Cytyc Corp.). The location of the lavaged duct(s) was noted on an 8×8 nipple grid, and the duct orifice was identified with a knotted piece of prolene suture. The 12 o’clock axis of the areola was marked with a skin pen, and the nipple photographed. When women returned for repeat DL, every attempt was made to cannulate ducts that had been previously lavaged (matched ducts). New fluid yielding ducts were also lavaged if any were identified.

Analysis of Cells

Samples were processed as previously described 1. Briefly, the lavage effluent was centrifuged and the cell pellet resuspended in 20mL of Preservcyt (Cytyc Corp.) solution. A ThinPrep slide (Cytyc Corp.) was prepared from ¼ of the cell suspension and stained using the Papanicolaou technique 7. Cytology was evaluated by two observers (RN and SM) and categorized as insufficient cellular material for cytologic diagnosis (ICMD), benign, mild atypia, severe atypia, or malignant, as described previously, using consensus criteria developed for interpretation of ductal lavage samples. 3. Discordant diagnoses were resolved for the final analysis by joint review. In the analysis by woman, the worst cytologic diagnosis was used; i.e., if two ducts showed benign cytology but a third duct showed mild atypia, the woman was designated as having mild atypia for that procedure. A second aliquot was used for immunohistochemical (IHC) evaluation of ERα , using heat antigen retrieval (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and a 1:200 dilution of Clone SP1 (Lab Vision Corporation, Fremont, CA). A third aliquot was used for double IHC staining of the nuclear protein Ki-67 and the cytoplasmic protein COX-2 1. Mouse monoclonal antibodies Ki-67, clone MIB-1 (DakoCytomation) diluted 1:200 and COX-2 (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI) diluted 1:100 were used sequentially, followed by color development (3,3′-diaminobenzidine for ER-α and COX-2 and Vector red for Ki-67. The validity of the double-staining procedure was established in MCF-7 cells, using single-label staining for Ki-67 and COX-2 compared to the results of dual-staining. There was excellent correspondence of the fraction of labeled cells in single and dual-stained slides over three separate experiments. The labeling index (LI) for each marker was calculated by counting positively and negatively stained epithelial cells (average of 1,000 cells per slide). A colocalisation index (colocalisation LI) was calculated as cells expressing both COX-2 and Ki-67. The intra-observer variability was assessed by blinded repetition of counts on 20 random IHC slides each for ER-α and Ki-67-COX-2.

A minimum of 100 cells per slide (average 1000 cells) was counted and the labeling index (LI) for each marker was calculated per duct as the number of positive cells divided by the total epithelial cell number. For each duct, the number of epithelial cells on all slides was summed to generate the total cell number per duct. The total cell number per woman was the sum of epithelial cells from all ducts lavaged during a single procedure; a woman had sufficient cellularity for analysis if she had at least one cellular duct at both timepoints. Total epithelial cell number was categorized as insufficient (<100 cells), borderline (100-399 cells), sufficient (400-999 cells), moderate (1000-4999 cells), and abundant (5000 or more cells). The biomarker indices were generated per woman as the sum of the number of positive cells from all ducts divided by the sum of the number of epithelial cells from all ducts, expressed as a percentage.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done both by woman and by matched duct. Subject age and 5 year breast cancer risk estimates were compared between the tamoxifen and observation groups using the independent sample t-test. Race and menopausal status was compared between the groups using Fisher’s exact test. Cell yield and cytology were categorized into five ordinal categories before analysis. Ordinal data were compared between the baseline and six month lavage using the weighted kappa statistic and 95% confidence interval. Spearman correlations and accompanying t-test for zero correlation were used to correlate baseline and six month markers measured in the same woman. Median biomarker levels were compared between the groups using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. When analyses were done by matched duct, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for clustered samples was used 8. Cytology was compared between groups using the Fisher’s exact test by woman and by duct. When adjusting for multiple ducts within a woman, cytology was analyzed using the test for proportions accounting for such clustering as described by Donner and Klar 9. Patients with missing data were excluded from the individual analysis for which the data was missing.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

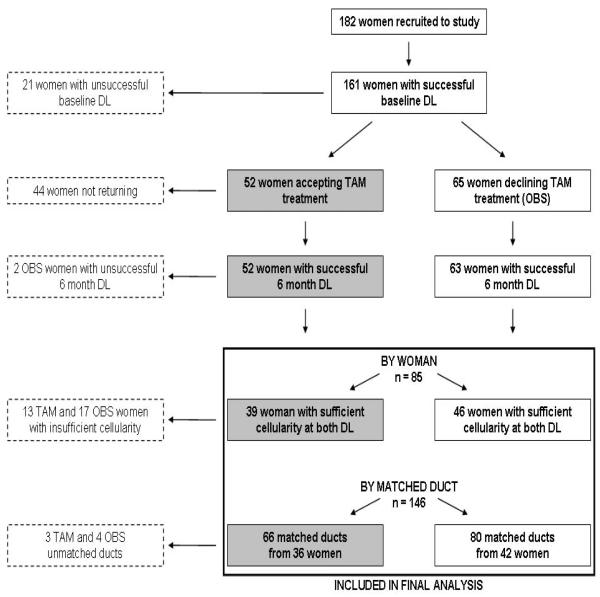

The success of ductal lavage (DL) procedures on the 182 women recruited to the study is presented in Figure 1. Of the total study population, 161 women (88%) had at least one duct lavaged at baseline; 117 women (64%) had sufficient cellularity for analysis at baseline. Women who underwent baseline DL were asked to return for a repeat lavage at six months. Of 161 women, 44 (27%) did not return for reasons including difficulty with travel and work schedule; only 4 women stated that their unwillingness to return was due to pain of the procedure. Tamoxifen acceptance by the 117 women with sufficient cellularity for analysis at baseline was good: 52 (44%) chose tamoxifen treatment and the remaining 65 (56%) chose observation.

Figure 1.

Study Outline

In the subsequent analyses in this report, the “by woman” analyses focus on the 85 women with sufficient cellularity at both time-points (i.e., ≥100 cells in at least one duct at both time-points), of whom 39 accepted tamoxifen therapy and 46 declined. In 78 of these 85 women, a total of 146 ducts could be recannulated and lavaged again at the six month time-point (designated “matched” ducts). These are included in the “by matched duct” analyses because the lavaged ducts were identical between baseline and repeat lavage. In the remaining 7 women, the ducts lavaged at baseline and six months were different, and therefore these 7 women are not included in the “matched duct” analysis. The median number of ducts lavaged at each time point was similar in the tamoxifen and observation groups, as was the number of ducts yielding more that 100 epithelial cells on at least one slide. The demographic characteristics of the 85 women with sufficient cellularity for analysis are presented in Table 1, which also shows the number of lavaged ducts and the biomarker values at baseline for the whole study population and the two analytic groups.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics

| All Women (n = 85) |

Tamoxifen (n = 39) |

Observation (n = 46) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Range) | Mean (Range) | Mean (Range) | p* | ||

| Age (years) | 50 (33-64) | 51 (42-63) | 49 (33-64) | 0.10 | |

|

| |||||

| 5 Year Risk Estimate | 3.0 (0.6-6.9) | 3.1 (1.7-6.9) | 3.0 (0.6-5.6) | 0.64 | |

|

|

|||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p ** | ||

|

| |||||

| Cancer Diagnosis | |||||

| DCIS | 6 (7) | 5 (13) | 1 (2) | 0.09 | |

| Invasive† | 9 (11) | 5 (13) | 4 (9) | 0.73 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 69 (81) | 35 (90) | 34 (74) | 0.09 | |

| Other | 16 (19) | 4 (10) | 12 (26) | ||

| Menopausal Status (b/6)‡ | |||||

| Pre/Pre | 32 (38) | 10 (26) | 22 (48) | 0.04 | |

| Post/Post | 41 (48) | 19 (49) | 22 (48) | 0.99 | |

| Pre/Post | 12 (14) | 10 (26) | 2 (4) | 0.01 | |

|

|

|||||

| Baseline | Biomarker | Median(Mean) | Median(Mean) | Median(Mean) | p *** |

|

|

|||||

| ER | 24.59(25.26) | 27.98(29.23) | 19.88(21.88) | 0.002 | |

| Ki67 | 0.11(0.59) | 0.32(0.57) | 0.11(0.50) | 0.30 | |

| Cox2 | 40.00(42.43) | 46.15(44.97) | 36.64(38.14) | 0.10 | |

|

No. lavaged ducts

per woman |

|||||

| All | 3.0(2.98) | 2.0(2.72) | 3.0(3.2) | 0.05 | |

| Cell counts ≥100 | 2.0(2.46) | 2.0(2.44) | 2.0(2.48) | 0.47 | |

|

| |||||

| 6 Month | Biomarker | ||||

| ER | 22.17(22.88) | 23.86(24.25) | 20.14(21.43) | 0.18 | |

| Ki67 | 0.00(0.31) | 0.00(0.20) | 0.08(0.42) | 0.25 | |

| Cox2 | 38.91(39.25) | 35.09(38.88) | 31.67(35.51) | 0.71 | |

|

Median lavaged

ducts per woman |

|||||

| All | 3.0(3.04) | 3.0(2.92) | 3.0(3.13) | 0.23 | |

| Cell counts ≥100 | 2.0(2.29) | 2.0(2.18) | 2.0(2.39) | 0.13 | |

p-value from two-sided independent sample t- test

p-value from two-sided Fisher’s exact test

p-value from Wilcoxon signed-rank test

T 1a/b carcinoma in contralateral breast

self-reported at baseline (b) and 6 month (6) DL

Menstrual Cycle Phase

Forty-four women were premenopausal at study entry and were menstruating regularly. Baseline DL was performed in the follicular phase in 24 women, and in the luteal phase in 20 women (Table 2). Our study design stipulated that the second DL procedure be performed in the same phase as the entry procedure, but despite all attempts to achieve this, the phase at the two time-points was discordant in 12 women because some women who were premenopausal at entry developed irregular periods or ceased menstruation during the six months following study entry (Table 1). This was more frequent in the tamoxifen group (p=0.01).

Table 2.

Summary of Cellular Markers by Menstrual Status at Baseline Ductal Lavage

| By Woman (n = 85) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Premenopausal (n = 44) |

Postmenopausal (n = 41) | ||

| Follicular (n = 24) | Luteal (n = 20) | ||

| Median (IQ range) | Median (IQ range) | Median (IQ range) | |

| ER LI | 25 (18-38) | 17 (13-29) | 25 (19-34) |

| Ki-67 LI | 0.14 (0.04-1.07) | 0.17 (0.04-0.58) | 0.11 (0-0.50) |

| COX-2 LI | 44 (29-53) | 44 (21-49) | 37 (30-60) |

| Cell No | 21782 (13782-36816) | 11635 (6796-23074) | 12087 (6518-22713) |

|

|

|||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| |||

| Cytology | |||

| ICMD | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| Benign | 10 (42) | 11 (55) | 27 (66) |

| Atypia | 13 (54) | 9 (45) | 12 (29) |

| By Duct (n = 209) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Premenopausal (n = 120) |

Postmenopausal (n = 89) | ||

| Follicular (n = 71) | Luteal (n = 49) | ||

| Median (IQ range) | Median (IQ range) | Median (IQ range) | |

| ER LI | 24 (16-35) | 17 (10-25) | 25 (17-34) |

| Ki-67 LI | 0.09 (0-0.97) | 0.09 (0-0.66) | 0.10 (0-0.47) |

| COX-2 LI | 40 (28-56) | 34 (18-46) | 40 (28-60) |

| Cell No | 6531 (4831-11599) | 4655 (1841-9217) | 6366 (2920-11875) |

|

|

|||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

| |||

| Cytology | |||

| ICMD | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) |

| Benign | 45 (63) | 39 (80) | 62 (70) |

| Atypia | 24 (34) | 10 (20) | 23 (26) |

IQ, interquartile range

ICMD, insufficient cellular material for diagnosis

Cytology, cell number, and biomarker expression at baseline lavage were examined descriptively by menstrual cycle phase in the 85 women and 209 ducts lavaged at baseline (Table 2). The frequency of cytologic atypia was similar across menstrual phase and was observed in 54% and 45% of women in the follicular and luteal phases, respectively, and was lower in postmenopausal women (29%). When analyzed by duct, the proportion of samples exhibiting cytologic atypia was similar between follicular phase, luteal phase, and postmenopausal women (34, 20, and 26%, respectively, Fisher’s exact p=0.97). Cell number (when summed across ducts) was higher in follicular phase than in luteal phase samples, and was similar between luteal phase and postmenopausal samples. In agreement with published studies, there was a trend for ERα LI to be lower, in women who underwent DL during the luteal phase, compared to the follicular phase 10-12. There was no difference in the Ki-67 or COX-2 LI between women undergoing DL in the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. By woman, cellular atypia was positively correlated with epithelial cell number (p<0.0001), as was cellular atypia with Ki-67 LI (p=0.01). By duct, epithelial cell number was positively correlated with atypia (p<0.0001).

Reproducibility of Cellular Parameters in the Observation Group

Cytologic diagnosis, the number of epithelial cells obtained, and the ERα, Ki-67, and COX-2 labeling indices (LIs) were compared across time-points in the observation group to assess the reproducibility of these measures (Table 3). There was a decline in the total number of epithelial cells obtained between the baseline and six month lavage. There was good correlation between the ERα LI at both time-points by woman (r=0.49, p=0.0008) and by matched duct (r=0.25, p=0.04). The correlation was borderline for COX-2 by woman (r=0.31, p=0.05) and significant by matched duct (r=0.27, p=0.03). The correlation between Ki-67 LI at both time-points was non-significant by woman (r=0.18, p=0.26) and by matched duct (r=0.10, p=0.40), as shown in Table 3. The Kappa statistic (95% confidence interval) for agreement of cytological diagnosis between time points in the observation group was 0.10 (-0.15, 0.35) by woman and 0.05 (-0.16, 0.26) by matched duct.

Table 3.

Reproducibility of Cellular Markers at Baseline and Six Month Ductal Lavage Samples in the Observation Group

| By Woman (n = 46) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER LI | Ki-67 LI | COX-2 LI | Cell No | |

| Women | 44 | 41 | 41 | 46 |

| Baseline Median | 20 | 0.11 | 37 | 13324 |

| 6 Month Median | 20 | 0.08 | 32 | 8118 |

| Spearman Correlation | 0.49 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.43 |

| p | 0.0008 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.003 |

| By Matched Duct (n = 80) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER LI | Ki-67 LI | COX-2 LI | Cell No | |

| Matched Ducts | 71 | 71 | 71 | 80 |

| Baseline Median | 20 | 0.08 | 36 | 6599 |

| 6 Month Median | 20 | 0 | 36 | 3406 |

| Spearman Correlation | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| p | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.47 |

r, Spearman correlation coefficient

Choice of tamoxifen therapy

Of the 85 women who had sufficient cells for analysis at two time points, 39 accepted tamoxifen therapy and 46 declined. Tamoxifen users were not significantly older than non-users (mean age 51 years versus 49 years, p=0.136). The fraction of tamoxifen users who demonstrated cytological atypia at baseline DL (15/39, 39%) was similar to those who declined tamoxifen (18/46 or 39%). A diagnosis of DCIS or T1a or T1b carcinoma in the contralateral breast was more frequent among tamoxifen users than in the observation group (26% vs. 11%) but not significantly so. Of those participants who did not have a history of breast cancer, the mean 5-year breast cancer risk estimate was 3.1 for the tamoxifen users, compared to 3.0 for those who declined (p=0.625).

Effect of Tamoxifen Therapy on Cellular Parameters

In the 85 women (39 on tamoxifen and 46 who declined tamoxifen), the fraction of tamoxifen users who demonstrated cytological atypia at baseline DL (16/39, 41%) was similar to those who declined tamoxifen (18/46, 39%). In the tamoxifen group, 36% of women and 23% of matched ducts showed improvement in cytology, whereas in the observation group improved cytology was observed in 22% of women and 18% of matched ducts. There was also deterioration in cytology findings, from benign to mild atypia; in the tamoxifen group this occurred in 13% of women and 9% of matched ducts, compared to worsened cytology in 17% of women and 15% of matched ducts in the observation group. Thus improvement was more frequent than worsening of cytology in the tamoxifen group than in the observation group, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Reductions in ERα, Ki-67, and COX-2 from baseline to six months were observed in the tamoxifen group, and were significant for Ki-67 by woman (p=0.04) and by matched duct (p=0.002). When the analyses were adjusted for multiple ducts within women, the differences in Ki-67 were still significant (p=0.03; Table 4). However, these findings should still be considered tentative since the fraction of Ki-67 positive cells was very low. In the tamoxifen group, median Ki-67 LI went from 0.32 to 0, and in the observation group from 0.11 to 0.08. Additionally, there was a larger proportion of women in the tamoxifen group who had a history of early breast cancer. The decrease in ERα was also greater in the tamoxifen group, but was of borderline significance when the analyses were adjusted for multiple ducts per woman (p=0.07). For COX-2, there were no significant differences by woman or by matched duct.

Table 4.

Tamoxifen-Related Biomarker Changes* in Ductal Lavage Samples

| Median Difference* By Woman (n = 85) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER LI median (IQ range) |

Ki-67 LI median (IQ range) |

COX-2 LI median (IQ range) |

Cytology | ||

| Improved | Worsened | ||||

| Tamoxifen | -1.85 (-13.68, 5.09) | -0.16 (-0.65, 0.00) | -7.10 (-24.47, 8.04) | 36% (14/39) | 13% (5/39) |

| n | 37 | 36 | 36 | ||

| Observation | -0.62 (-6.52, 4.09) | 0.00 (-0.12, 0.21) | -2.35 (-14.90, 8.96) | 22% (10/46) | 17% (8/46) |

| n | 44 | 41 | 41 | ||

| Difference | -1.23 | -0.16 | -4.75 | ||

| p-value † | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.23¶ | 0.76¶ |

| Median Difference* By Matched Duct (n = 146) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER LI median (IQ range) |

Ki-67 LI median (IQ range) |

COX-2 LI median (IQ range) |

Cytology | ||

| Improved | Worsened | ||||

| Tamoxifen | -7.06 (-16.42, 6.63) | -0.11 (-0.43, 0.00) | -2.97 (-24.27, 8.01) | 23% (15/66) | 9% (6/66) |

| n | 58 | 59 | 59 | ||

| Observation | -0.49 (-8.74, 8.32) | 0.00 (-0.20, 0.30) | -3.02 (-13.33, 8.94) | 18% (14/80) | 15% (12/80) |

| n | 71 | 71 | 71 | ||

| Difference | -6.57 | -0.11 | 0.05 | ||

| p-value † | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.40 | 0.53¶ | 0.32¶ |

| adjusted p-value †† | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.45‡ | 0.27‡ |

six month lavage minus baseline lavage

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test comparing medians between observation and tamoxifen groups

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test comparing medians between observation and tamoxifen groups, adjusting for multiple ducts within women

Fisher’s exact test comparing proportions between observation and tamoxifen groups

Donner and Klar test comparing proportions between observation and tamoxifen groups, adjusting for multiple ducts within women

Inter-observer Correlations of Cytologic Diagnosis

We performed a comparative analysis of cytologic diagnosis to assess the reproducibility of results between two experienced cytopathologists (RN and SM). The results presented in Table 5 include all samples (baseline and six months) and indicate that there was good correlation between the two observers. Of the 306 ducts analyzed by both observers (RN and SM), cytologic diagnosis was concordant in 205 (67%) of samples: 144 were diagnosed with benign cytology by both observers; 20 ducts were diagnosed with mild atypia and 41 had insufficient cellular material for diagnosis; however, 101 samples (33%) were given discordant diagnoses of insufficient, benign or mild atypia. The weighted kappa statistic was 0.44 (95% CI=0.36-0.53).

Table 5.

Inter-observer Variability of Cytological Diagnosis for 306 Ducts Analyzed by Two Observers

| First Observer (RN) | Second Observer (SM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICMD | Benign | Mild Atypia | Severe Atypia | Total | |

| ICMD | 41 | 32 | 6 | 0 | 79 |

| Benign | 3 | 144 | 41 | 1 | 189 |

| Mild Atypia | 0 | 16 | 20 | 0 | 36 |

| Severe Atypia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 44 | 192 | 69 | 1 | 306 |

ICMD, insufficient cellular material for diagnosis

Shaded cells depict samples with concordant diagnoses by two observers

Weighted κ for all ducts: Good (0.44; 95% CI: 0.36, 0.53)

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that DL samples can be used for the measurement of biomarkers and that sufficient cellularity for analysis at the initial lavage was obtained from 70% of woman 1. Here we report the results of serial monitoring of breast epithelium, comparing women treated with tamoxifen therapy to women who chose observation. We chose a six-month interval for the assessment of biomarker modulation since this is frequently employed in Phase II prevention studies 13;14; and demonstration of biomarker stability at the six-month time-point would be a good starting point for future studies. Additionally, we intended to assess the modulation of cytologic atypia by tamoxifen, and it appeared unlikely that a shorter interval of therapy would achieve this. A longer interval may have affected compliance for return lavage and would have increased the duration and therefore the expense of the study.

We found that sufficient numbers of epithelial cells for biomarker analysis were obtained in only 47% (85/182) of women at both time-points due to attrition of the study population at several levels (see Figure 1). In the tamoxifen group, we saw the expected declines in the widely used biomarkers that we chose to study, selected for their expected response to tamoxifen therapy (cytologic atypia, ERα and Ki-67); however, the attrition of the sample size and the resulting decrease in power, along with a high level of variability in cytologic and immunohistochemical parameters in the observation group, rendered it difficult to identify statistically significant changes between the tamoxifen and observation groups. We saw trends towards improvement in cytologic findings and ERα expression. The Ki-67 labeling index was substantially lower in our DL samples than the ∼2% value reported for normal breast samples obtained by random fine needle aspiration or core biopsy. This may be related to the fact that the luminal cells that are presumably exfoliated and collected during a DL procedure have lower proliferation rates. However, we did see a significant decline in Ki-67 labeling indices between the tamoxifen and observation groups by woman (p=0.04) and by matched duct (p=0.002), and after adjustment for multiple ducts per subject (p=0.03). This was despite poor reproducibility of Ki-67 LI across the two time-points, suggesting a strong effect of tamoxifen on cell proliferation. The poor reproducibility of in IHC biomarkers may in part be attributed to the fact our cellularity threshold for inclusion of IHC slides was >100 epithelial cells, in contrast to studies utilizing random fine needle aspiration samples where Fabian et. al. have used a threshold of >500 epithelial cells. The higher threshold is more feasible for random FNA material, where 16-20 needle passes from two breasts are pooled, than for DL samples which are typically handled as separate samples for each individual duct. This consideration was partly what drove us to examine the question of whether or not maintaining separate duct samples has any advantage over pooling them (see below). Nevertheless, the mean number of cells on IHC slides in our study was 1000, and only 9% were in the 100-500 cell range.

When we designed our study in 2002-2003, there was significant interest in cytologic findings in DL samples. Cytologic atypia had been identified as a potential surrogate endpoint in Phase 2 prevention studies 15 and although its reversibility had never been demonstrated, we postulated that using DL to sample epithelial cells from the same ductal tree over time, it may be feasible to demonstrate reversal of cytologic atypia in a given duct. We did not restrict entry to women with atypical samples at baseline because we wanted to assess both aspects of variability in cytology: change from atypia to benign, and from benign to atypical. We report here that cytologic findings from the same duct were variable over time; however, in the tamoxifen group, changes were more likely in the direction of improvement from mild atypia to benign cytology (44% improvement) than in the observation group (16% improvement; Table 4). Although we did not see a statistically significant difference in the cytologic improvement between tamoxifen and observation groups, the relationships between atypia and other parameters were similar to those observed in previous studies of DL 16 and random fine needle aspiration 17 in healthy, high risk women. Thus, epithelial cell number was positively correlated with atypia (p<0.0001), as was cellular atypia with Ki-67 LI (p=0.01). In addition, as reported described 10;18, the ERα LI was lower, in women who underwent DL during the luteal phase when compared to women undergoing DL in the follicular phase. There has been some discussion regarding the possibility that mild atypia in DL samples may be non-specific and related to menstrual cycle changes. We did not find any specific differences in cytologic atypia rates by menstrual cycle phase or menopausal status.

Since the interpretation of cytology has a subjective component, we included a blinded review of cytologic diagnosis by an expert reference cytopathologist in our study design. This analysis showed that the variability of cytologic diagnosis is only partly related to inter-observer variability of interpretation, as suggested by the moderate kappa statistic of 0.44. This is very similar to our previous findings in women who underwent ductal lavage before mastectomy 1-3. Discordance in interpretation was mostly attributable to samples which exhibited benign or mildly atypical cytology. Similar results were documented in a pre-mastectomy DL study 19 where mild atypia constituted one-third of samples and was the most challenging and least reproducible diagnostic category. In another study of DL reproducibility, 14/69 women entered into the study underwent two DL procedures and the reproducibility of cellularity and cytology was very similar to that observed in our study 20.

We included pre- and post-menopausal women in this study because tamoxifen is effective in both groups. By design, we did not mandate the menstrual cycle phase for the entry lavage, since the optimal menstrual cycle phase for breast epithelial sampling in studies of risk and prevention is not known. Some investigators perform such sampling only in follicular phase 21 and others do not time sampling by phase 22. We have found in a previous case-control study utilizing breast biopsy samples that biomarkers differences may be more marked in the luteal than in the follicular phase 18. Additionally, fixing the sampling in a specific phase adds to the difficulty of scheduling and recruitment. We reasoned therefore that it would be optimal to allow the first sample to be collected in either follicular or luteal phase, but we would limit within-person variability by asking women to return for the repeat procedure in the same phase of the cycle as the initial lavage. We would then be able to explore the advantages of sampling in one phase over the other and apply the results to the design of future studies. However, women on tamoxifen developed irregular periods or ceased menstruation during the course of the study significantly more frequently, producing some variation in the endocrine status of women at the two time-points, which may contribute to the variability in the DL findings. Our experience highlights the importance of uniformity in menstrual phase and menopause status, and the difficulty of prevention trials designed in an age group which straddles menopause. Although the age group of 40-60 is the most appropriate for testing prevention agents in terms of breast cancer risk and motivation, the changing endocrine environment presents a challenge.

Although DL allows for the repeated sampling of the breast epithelium from the same duct over time, with an expected improvement in the reproducibility of biomarker findings, the analysis of several samples per procedure adds to the expense of the procedure, the expense of laboratory assays, and the complexity of statistical analysis. Our study is the first to assess the advantage of analyzing each duct separately versus averaging all duct samples from a single DL procedure. The descriptive analysis of cellular markers at baseline was similar whether examined by woman or by duct (Table 2). Furthermore, analyses of the reproducibility of cellular markers at both time-points in the observation group showed no advantage for the by matched duct analysis (Table 3) and the tamoxifen-related changes in biomarkers showed only a marginal advantage when analyzed by woman or by matched duct (Table 4). We conclude from this experience that pooling DL samples from different ducts would increase the efficiency of this sampling method.

We experienced high attrition rate in the study subjects related to a variety of factors; these included the inability to perform baseline DL (n=21), failure to return for a second lavage (n=44), inability to perform repeat lavage on subjects who returned (n=2), insufficient cellular material for analysis from both lavage procedures (n=30), and unmatched ducts yielding sufficient cells for analysis in (n=7). Thus, of 182 women recruited to the study, 85 (47%) had successful DL at both time-points with sufficient cellular material for analysis, and 78 (43%) had matched ducts with sufficient cellular material for analysis. The largest sources of subject attrition were failure to return (due to travel distance and work schedules) for the second DL procedure (44/182, 24%) and insufficient cells at two time-points (30/182, 16%). Our results are somewhat better than those reported in a previous smaller study of DL at two time points 22. In that study, a total of 67 women were recruited, 22 (32%) did not return for the second procedure, and DL could be repeated six months later on 19 women (28%)

Two previous small studies have compared DL to random fine needle aspiration at a single time-point in very similar study populations and have found DL to have low cellular yield 23;24. In the larger of these 23, 86 women were recruited. DL could be performed in 38 ducts and samples adequate for cytologic assessment were obtained in 27/86 (31%) of subjects. We used a higher threshold for adequacy (100 rather than 10 epithelial cells) and found a higher proportion of adequate samples at baseline (128/182 women, 70%) than in these studies; however, the high attrition rate discussed above, some of which is related to poorer cell yield at the second DL procedure, prevents us from endorsing DL as an improvement over existing tools for biomarker assessment in healthy high risk women since we do not see any improvement in reproducibility of biomarkers when the analyses are restricted specifically to ducts that were recannulated at two time-points.

In summary, we observed the expected trends in tamoxifen-related biomarkers using ductal lavage for breast epithelial sampling of the healthy, high risk breast. However, a 53% attrition rate of subjects from recruitment to biomarker analyses, the expense of the catheter, the time required for the procedure, and the analysis of multiple samples per woman at each time-point, renders ductal lavage an extremely expensive method of breast epithelial sampling. This high cost and the variability of findings over time in the observation group means that this procedure is of questionable utility for biomarker assessment over time in high risk women.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This work was supported by the Bluhm Family Program for Breast Cancer Early Detection and Prevention, and NIH/NCI P50 CA89018-02 (Avon Progress for Patients Supplement); HAL was supported by NCI grant R25 CA100600.

Footnotes

Disclosure regarding previous presentations of this work: Portions of this work were presented by the first author as an oral abstract at the 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, June 1-5, 2007, in Chicago, IL

Disclaimers: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhandare D, Nayar R, Bryk M, Hou N, Cohn R, Golewale N, Parker NP, Chatterton RT, Rademaker A, Khan SA. Endocrine biomarkers in ductal lavage samples from women at high risk for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2620–2627. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan SA, Wolfman JA, Segal L, Benjamin S, Nayar R, Wiley EL, Bryk M, Morrow M. Ductal Lavage Findings in Women with Mammographic Microcalcifications Undergoing Biopsy. Ann Surg. 2005;12:689–696. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan SA, Wiley EL, Rodriguez N, Baird C, Ramakrishnan R, Nayar R, Bryk M, Bethke KB, Staradub VL, Wolfman J, Rademaker A, Ljung BM, Morrow M. Ductal lavage findings in women with known breast cancer undergoing mastectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1510–1517. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N, Atkins J, Daly M, Wieand S, Tan-Chiu E, Ford L, Wolmark N. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, Mulvihill JJ. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD. Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer. 1994;73:643–651. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3<643::aid-cncr2820730323>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall PN. Papanicolaou staining--a review. Microsc. Acta. 1983;87:233–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosner B, Glynn RJ, Lee ML. Incorporation of clustering effects for the Wilcoxon rank sum test: a large-sample approach. Biometrics. 2003;59:1089–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2003.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donner A, Klar N. Methods for comparing event rates in intervention studies when the unit of allocation is a cluster. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994;140:279–289. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battersby S, Robertson BJ, Anderson TJ, King RJB, McPherson K. Influence of menstrual cycle, parity and oral contraceptive use on steroid hormone receptors in normal breast. Br J Cancer. 1992;4:601–607. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd M, Hildebrandt RH, Bartow SA. Expression of the estrogen receptor gene in developing and adult human breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;37:243–251. doi: 10.1007/BF01806506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams G, Anderson E, Howell A, Watson R, Coyne J, Roberts SA, Potten CS. Oral contraceptives (OCP) use increases proliferation and decreases oestrogen receptor content of epithelial cells in the normal human breast. Int J Cancer. 1991;48:206–210. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabian CJ, Kimler BF, Brady DA, Mayo MS, Chang CH, Ferraro JA, Zalles CM, Stanton AL, Masood S, Grizzle WE, Boyd NF, Arneson DW, Johnson KA. A Phase II Breast Cancer Chemoprevention Trial of Oral alpha-Difluoromethylornithine: Breast Tissue, Imaging, and Serum and Urine Biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3105–3117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabian CJ, Kimler BF, Zalles CM, Khan QJ, Mayo MS, Phillips TA, Simonsen M, Metheny T, Petroff BK. Reduction in proliferation with six months of letrozole in women on hormone replacement therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Shaughnessy JA, Kelloff GJ, Gordon GB, Dannenberg AJ, Hong WK, Fabian CJ, Sigman CC, Bertagnolli MM, Stratton SP, Lam S, Nelson WG, Meyskens FL, Alberts DS, Follen M, Rustgi AK, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Scardino PT, Gazdar AF, Wattenberg LW, Sporn MB, Sakr WA, Lippman SM, Von Hoff DD. Treatment and prevention of intraepithelial neoplasia: an important target for accelerated new agent development. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:314–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cazzaniga M, Severi G, Casadio C, Chiapparini L, Veronesi U, Decensi A. Atypia and Ki-67 expression from ductal lavage in women at different risk for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 2006;15:1311–1315. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan QJ, Kimler BF, Clark J, Metheny T, Zalles CM, Fabian CJ. Ki-67 expression in benign breast ductal cells obtained by random periareolar fine needle aspiration. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:786–789. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan SA, Rogers MA, Khurana KK, Meguid MM, Numann PJ. Estrogen receptor expression in benign breast epithelium and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:37–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.37. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brogi E, Robson M, Panageas KS, Casadio C, Ljung BM, Montgomery L. Ductal lavage in patients undergoing mastectomy for mammary carcinoma: a correlative study. Cancer. 2003;98:2170–2176. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visvanathan K, Santor D, Ali SZ, Hong IS, Davidson NE, Helzlsouer KJ. The importance of cytologic intrarater and interrater reproducibility: the case of ductal lavage. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 2006;15:2553–2556. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabian CJ, Kimler BF, Zalles CM, Klemp JR, Kamel S, Zeiger S, Mayo MS. Short-Term Breast Cancer Prediction by Random Periareolar Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology and the Gail Risk Model. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.15.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visvanathan K, Santor D, Ali SZ, Brewster A, Arnold A, Armstrong DK, Davidson NE, Helzlsouer KJ. The reliability of nipple aspirate and ductal lavage in women at increased risk for breast cancer--a potential tool for breast cancer risk assessment and biomarker evaluation. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 2007;16:950–955. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arun B, Valero V, Logan C, Broglio K, Rivera E, Brewster A, Yin G, Green M, Kuerer H, Gong Y, Browne D, Hortobagyi GN, Sneige N. Comparison of ductal lavage and random periareolar fine needle aspiration as tissue acquisition methods in early breast cancer prevention trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:4943–4948. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zalles CM, Kimler BF, Simonsen M, Clark JL, Metheny T, Fabian CJ. Comparison of cytomorphology in specimens obtained by random periareolar fine needle aspiration and ductal lavage from women at high risk for development of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]