Abstract

This study examined associations between televised news regarding risk for future terrorism and youth outcomes and investigated the effects of training mothers in an empirically based approach to addressing such news with children. This approach—Coping and Media Literacy (CML)—emphasized modeling, media literacy, and contingent reinforcement and was compared via randomized design to Discussion as Usual (DAU). Ninety community youth (aged 7−13 years) and their mothers viewed a televised news clip about the risk of future terrorism, and threat perceptions and state anxiety were assessed preclip, postclip, and postdiscussion. Children responded to the clip with elevated threat perceptions and anxiety. Children of CML-trained mothers exhibited lower threat perceptions than DAU youth at postclip and at postdiscussion. Additionally, CML-trained mothers exhibited lower threat perceptions and state anxiety at postclip and postdiscussion than did DAU mothers. Moreover, older youth responded to the clip with greater societal threat perception than did younger youth. Findings document associations between terrorism-related news, threat perceptions, and anxiety and support the utility of providing parents with strategies for addressing news with children. Implications and research suggestions are discussed.

Keywords: terrorism, anxiety, threat, media, children

Terrorist events over the past 15 years (e.g., on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, the U.S.S. Cole, the World Trade Center, and the Pentagon, as well as attacks in Egypt, Russia, Kenya, India, London, Iraq, the Philippines, Madrid, and Riyadh, among others) have substantially altered the ecology within which the development of modern youth unfolds. The goal of terrorism (defined in Title 22 of the U.S. Code, Section 2656f[d] as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against non-combatant targets by sub-national groups. . .intended to influence an audience”; U.S. Department of State, 2005) is by design grander in scope than simply causing physical injury and destruction of property. Indeed, research documents that contact with terrorism is associated with psychological distress, traumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Comer & Kendall, 2007; Hoven et al., 2005; La Greca, 2007; La Greca & Silverman, 2006; Pfefferbaum et al., 1999; Schuster et al., 2001).

The majority of empirical work on terrorism and youth has investigated youth who have come into proximal contact with a terrorist attack (i.e., those located in a city under terrorist attack and/or those who lost a loved one in an attack). This literature suggests that a substantial proportion of such youth evidences a wide array of clinical needs and functional impairments months after an attack (e.g., Brown & Goodman, 2005; Hoven et al., 2005; Pfefferbaum et al., 2003).

Terrorists seek to communicate threat to the widest possible audience, and much has been written about their use of mass media (see Nacos, 2003). Technological advances and new trends in mass media provide a stage unlike any in history—a stage from which terrorist acts can reach a truly enormous audience. Given the large amount of time youth spend consuming media (e.g., American youth aged 8−14 years old watch >3 hr of TV/day; 20% of youth aged 2−17 watch >35 hr of TV/week; Gentile & Walsh, 2002; Roberts, Henriksen, & Foehr, 2004), it is not surprising that youth proximal and distal to an attack are exposed to an enormous amount of attack-related media (Hoven et al., 2005; Schuster et al., 2001). Research that has examined media-based contact with terrorist events suggests that such contact can have great effects upon children's emotional functioning, for example, PTSD symptoms, behavioral withdrawal, anxiety, and sleep problems (Hoven et al., 2005; Otto et al., 2007; Pfefferbaum et al., 2003; Phillips, Prince, & Schiebelhut, 2004; Schuster et al., 2001).

To examine the impact of terrorism on the psychological adaptation of youth, it is critical that we not only examine proximal and media-based contact with actual terrorist events but also examine the subsequently changed social ecology after terrorism has been perpetrated. Media presentations are now dominated by the recasting of daily social, cultural, and political events and decisions within the threat of future acts of terrorism. Since the 2001 attacks, U.S. televised news has increasingly covered terror threats, the issue of “future attacks,” and our potential vulnerabilities. Given the enormous amount of time youth spend watching television, a substantial proportion of youth are being exposed to this ongoing broadcast message of threat and alert.

Statistically, it is unlikely that the vast majority of American youth will ever come into proximal contact with a terrorist attack. However, within this climate of heightened awareness about terrorism and elevated vigilance, the vast majority of youth are at risk for exposure to “second-hand terrorism” (Comer & Kendall, 2007), in which disproportionate media presentations of the possibility (rather than probability) of being a direct victim of terrorism sets the stage for omnipresent threat and insecurity, countless false alarms, and pervasive anxiety. Second-hand terrorism may be particularly concerning in regard to youth, given that they are still developing a sense of security about their world and may have little control over the media they consume.

Given that a disproportionate cognitive emphasis upon the possibilities (rather than probabilities) of unwanted events lies at the heart of childhood anxiety disorders (Daleiden & Vasey, 1997), it is surprising that empirical work has yet to examine the impact of such media presentations on youth. Research unrelated to terrorism in the communications literature has suggested that televised news can have deleterious effects on children's global perceptions of threat and vulnerability. Gerbner and colleagues (Gerbner & Gross, 1976; Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1994; see also Morgan & Shanahan, 1997) examined TV's portrayal of a world more dangerous than the one in which the average viewer inhabits. That is, heavy TV viewing cultivates distorted perceptions of the world as more dangerous and threatening than it actually is for the average viewer. Indeed, research shows news exposure is associated with perceptions of problematic crime, even after controlling for crime rates in viewers’ neighborhoods (Romer, Jamieson, & Aday, 2003; Smith & Wilson, 2002).

Researchers have yet to examine how adults can best help youth process that which they see on television regarding future terrorism possibilities. Data indicate that television-viewing is very much a social family activity (Krosnic, Anand, & Hartl, 2003; Kubey & Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; St. Peters, Fitch, Huston, Wright, & Eakins, 1991). Numerous professional associations have offered guidelines for talking to youth about media presentations of terrorism possibilities, but the efficacy of these guidelines in reducing children's anxiety has not been examined empirically. Research unrelated to terrorism from the fields of clinical child psychology and communications may provide some direction. First, parents can serve as models of either fear or coping. Data support the contribution of modeling in the acquisition of fear and coping (Field, 2006; Gerull & Rapee, 2002; Kliewer et al., 2006; Menzies & Clarke, 1993; Muris, Steerneman, Merckelbach, & Meesters, 1996; Ollendick & King, 1991), and empirically supported family interventions for childhood anxiety disorders emphasize parental modeling in effecting change (Barrett, Dadds, & Rapee, 1996; Howard, Chu, Krain, Marrs-Garcia, & Kendall, 1999). Second, parents can offer commentary to guide youth inferences and help children to make sense of that which is portrayed on TV. Research supports the beneficial impact that skeptical parental commentary regarding televised images (e.g., “this is fake,” “no one could really get away with that”) can have upon children's comprehension of televised aggression (Collins, Sobol, & Westby, 1981; Nathanson, 1999). Similarly, parental promotion of children's media literacy (e.g., educating children about the media and the lack of proportionality inherent in brief TV news pieces, explaining the dramatic nature attached to televised news, introducing positive and hopeful aspects of the world situation not addressed in time-constrained news pieces) may help children better attend to the probability (as opposed to possibility) of personal terrorism victimization. Further, although the economic incentives for the media to report threat-related news have been noted (Klite, Bardwell, & Salzman, 1997), this is something with which youth are rarely familiar. Discussing with youth the news media's heavy reliance on dramatic coverage may help them distinguish the security of the world portrayed by the news from the likely security of their actual world.

Finally, research suggests that parental responses to children's anxiety can serve to maintain it (e.g., Barrett, Rapee, Dadds, & Ryan, 1996; Dadds, Barrett, Rapee, & Ryan, 1996). A child's perception of high personal vulnerability to a terrorist attack will likely persist if the child's parents support terrorism-related avoidance (e.g., mother saying, “That's a good point—it might be a bad idea to go to the ballgame”). In contrast, a child whose parents praise the child's more positive and adaptive statements (e.g., “I'm really proud of you; that's a great way to think of things”) may have an easier time coping. Although the literature suggests that modeling confidence, promoting media literacy, praising children for generating positive thoughts, and challenging children's anxious thoughts may be useful strategies for reducing youth anxiety and threat perceptions following televised presentations of terrorism possibilities, these strategies have yet to be evaluated against an appropriate control condition.

In the present study we examined associations between televised news regarding risk for future terrorism and children's anxiety and threat perceptions, and we investigated the effects of training mothers in an empirically based approach, coping and media literacy (CML), to addressing such news content with their children. CML was compared to undirected discussion as usual (DAU). Mother– child dyads together viewed a selected televised news clip about risk of future terrorism. Threat perceptions and state anxiety were assessed at preclip (T1), postclip (T2), and postdiscussion period (T3). It was hypothesized that youth whose mothers received CML training would fare better than DAU youth. In addition, half of the CML-trained mothers discussed the news clip after it was presented and half did not (CML-ND), affording examination of the relative importance of verbal versus nonverbal communications in guiding youth reactions to the news clip. Given work from the communications literature suggesting that older children are more likely than younger children to comprehend, as well as be frightened by, televised news (e.g., Smith & Wilson, 2002), it was hypothesized that age would be positively associated with increases in child state anxiety and threat perceptions.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 90 youth (7−13 years old; M = 10.8, SD = 2.0; 43 girls) from the Philadelphia area and their mothers. To assess the effects of CML and DAU for youth in the general public, we recruited a community sample from media advertisements and school-based outreach. As Philadelphia is a major metropolitan area with several potential terrorist targets (e.g., the Liberty Bell, Independence Hall), recruiting from this community afforded an appropriate sample. Forty-eight percent of the sample was Caucasian, 48% African-American, and 4% were reported as “other.“ Regarding total household income, 4.6% of the sample earned less than $9,999, 6.9% earned $10,000–$19,999, 6.9% earned $20,000–$29,999, 14.9% earned $30,000–$39,999, 12.6% earned $40,000–$49,999, 13.8% earned $50,000–$59,999, 6.9% earned $60,000–$69,999, 13.8% earned $70,000–$79,999, and 19.5% earned over $80,000. Participants were compensated $50 for their time. Participants had to be English-speaking, as the news clip shown to participants was in English. In addition, mothers were asked in a phone screening whether they allow their child to view televised news. Mothers who did not were not eligible for this study, ensuring that the study did not expose children to anything their parents would not otherwise permit them to see (the screener ruled out 4 mothers).

Measures

Child state anxiety

The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (Spielberger, 1973) is a 20-item child self-report of transitory perceptions of tension and apprehension and was administered at T1, T2, and T3. Respondents rate each item on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all; 4 = very much so). Item scores are summed, and scores range from 20 to 80. The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children–State has demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties and the ability to detect change in samples similarly aged to the present sample (see Silverman & Ollendick, 2005; Silverman & Rabian, 1999). Internal consistency was strong in the present sample (α = .83).

Maternal state anxiety

The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1970) is a 20-item adult self-report of transitory perceptions of tension and apprehension and was administered at T1, T2, and T3. Respondents rate each item on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all; 4 = very much so). Item scores are summed, and total scores range from 20 to 80. The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory–State has evidenced strong reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change (e.g., Barnes, Harp, & Jung, 2002; Kendall, Finch, Auerbach, Hooke, & Mikulka, 1976; Spielberger et al., 1970). Internal consistency was excellent in the present sample (α = .92).

Child threat perception

Consistent with methodology employed in the literature on child subjective probability judgment (e.g., Dalgleish et al., 1997), children were asked to rate the likelihood of future terror attacks on 7-point Likert scales (0 = definitely will not happen, 6 = definitely will happen). A visual aid was used to assist children's comprehension. Children were asked to provide two estimates on these Likert scales of the likelihood that (a) a terrorist attack will occur in the United States over the next year (terror threat [societal]) and that (b) a terrorist attack will directly affect them or their family (terror threat [personal]). Given evidence that personal and societal threat perceptions do not always respond uniformly to threat-related news (Romer et al. 2003), we examined the child's personal and societal estimates separately. To assess the specificity of study findings to terrorism-related threat perceptions, we collected parallel estimates at T1, T2, and T3 to assess the child's perceived likelihood of a major hurricane or flood occurring in the United States over the next year (hurricane/flood threat [societal]) or directly affecting them or their family (hurricane/flood threat [personal]).

Maternal threat perception

Consistent with methodology employed in the adult subjective probability judgment literature (e.g., Windschitl & Weber, 1999), mothers were asked to provide two percentages indicating their subjective estimation of likelihood of future terror attacks (i.e., “What do you think the likelihood is that a terrorist attack will occur in the US over the next year? There is a __ % chance”; “What do you think the likelihood is that a terrorist attack will directly affect you or your loved ones over the next year? There is a __ % chance”). Analyses examined societal and personal terror threat estimates separately. To assess the specificity of study findings to terrorism-related threat perceptions, we collected parallel estimates at T1, T2, and T3 to assess mothers’ perceived likelihood of a major hurricane or flood occurring in the United States over the next year (i.e., societal threat) or directly affecting their family (i.e., personal threat).

Televised News Clip

A 12-min news clip addressing risks of future terrorism was selected from a 2005 CNN special entitled “Defending America” (Cable News Network, 2005), a homeland security special geared toward consuming adults, which initially aired at 7 p.m. The clip was selected for its discussion of American vulnerabilities without implication of particular ethnic groups as likely to carry out terrorist acts, and for its discussion of future, rather than previous, attacks. Topics covered included nuclear threat, airport and rail security (with consideration of specific vulnerabilities to terrorism), and schools as potential targets of terrorism. In one segment, a reporter leaves bags unattended in New York City and Philadelphia train stations, as footage documents a prolonged lack of security response to the unattended bags. The clip concludes with a dramatization of a hypothetical scenario in which terrorists acquire and smuggle nuclear material into the United States. The destruction and loss of human life that could subsequently result is considered. Among four clips, this clip was unanimously selected by 4 child anxiety experts as most likely to elevate children's anxiety, without resulting in extended distress.

Discussion Conditions

CML (N = 60)

In CML, mothers were instructed to use a combination of modeling, social reinforcement, psychoeducation, and Socratic probing strategies to address the news clip. Mothers were directed to model confidence in their security, to offer praise when their child offered coping statements (e.g., “that's a great way to think of things; I'm really proud of you”), to help their child challenge dysfunctional statements, and not to express their own terrorism fears to their children. CML mothers were instructed to educate their children about the media and the lack of proportionality inherent in brief TV news pieces. Without trivializing the actual risks, mothers were instructed to help their child understand the precise probability (as opposed to possibility) of personal terrorism victimization, to explain the time constraints and dramatic nature attached to such news pieces, and to introduce positive and hopeful aspects of the world situation not addressed in the clip. Thirty CML-trained mothers discussed the video for 10 min with their children. For the other half of the CML-trained mothers (CML-ND; n = 30), there was no discussion: Mothers and children were placed in separate rooms for 10 min (the duration of the discussion period) following the clip. Study personnel who were located in another room watching CML-ND youth and mothers on monitors noted that the majority of youth spent the 10 min “looking around the room,” “sitting there,” or “drawing on a piece of paper they found in the room.” Personnel noted that the majority of CML-ND mothers “just sat there.”

DAU (N = 30)

DAU mothers did not receive CML and were instructed to react to the news clip with their child as they typically would at home. Including such a condition afforded a comparison of CML to the existing community standard of parent–child discussion following exposure to news of terrorism possibilities.

Procedure

All study procedures were conducted under the approval of and in compliance with the Temple University Institutional Review Board. Interested mother– child dyads contacted study personnel and underwent a brief phone screening. Qualifying mothers along with their children were scheduled for a 2-hr appointment. At their appointment, written informed consent and assent were obtained from mothers and children, respectively, and mothers and children then completed T1 assessments in separate rooms. Child forms were completed with the assistance of a graduate student. Mothers then participated in a 1-hr preparation for the condition to which they and their child were randomly assigned (see Discussion condition training for mothers) while the graduate student played games with the child in a separate room. After the mother was prepared, mother and child watched the news clip together. To ensure that all children received the same “dose” of news contact during presentation of the clip, and to afford systematic examination of the relative importance of verbal versus nonverbal communications in guiding youth reactions to the news clip, dyads were instructed to refrain from speaking to one another during the news clip presentation. Study personnel who were located in another room watching dyads on monitors during the presentation of the news clip confirmed that all dyads did indeed refrain from speaking during this time. The mother and child then separately completed T2 assessments. CML mothers were reminded to take the lead in accordance with their CML training; DAU mothers were reminded to react to the news clip the way in which they typically would if they were to see it at home. Mothers in CML and DAU were then reunited with their children. They were given 10 min together for discussion and then separately completed T3 assessments. In contrast, CML-ND mothers and youth were instructed to remain in their separate rooms until the experimenters were ready for the next task. After a 10-min period, mothers and children, still in separate rooms, completed T3 assessments. After T3, CML-ND mothers were reunited with their children and were then given 10 min to process the news clip. Consequently, no children left the experiment without the opportunity to process the clip with their mothers. Dyads received financial compensation and were debriefed at the end of their participation.

Discussion condition training for mothers

Prior to viewing the news clip, each mother individually received 60 min of preparation for the discussion condition to which she and her child were randomly assigned. Mothers were informed that they were about to watch a news clip with their children about terrorism and that they were being asked to react to the clip with their children for a period of 10 min following the clip according to specific instructions. CML and DAU training both consisted of three phases: (a) didactics (given via a self-administered Power Point presentation with a recorded voice and moving visual images), (b) role-playing, and (c) testing to ensure that mothers were sufficiently prepared for the condition to which they were assigned.

CML training

Mothers assigned to CML and CML-ND received CML training. Didactics entailed educating mothers on the principles of modeling, operant conditioning, and cognitive restructuring via a self-administered Power Point presentation; mothers were provided with examples of how to address various child statements and concerns from a CML standpoint (e.g., to help generate coping thoughts: “let's think—how many times has there been an attack in the last year?”; to reward coping thoughts: “that's a great way to look at it—I'm proud of you”). CML mothers were also educated about the media and provided with direction as to how to promote media literacy in children (a script of the CML didactic training presentation is available upon request). The CML didactic presentation was interspersed with video clips of child actors asking questions about the likelihood of future attacks. Clips included an actor playing the part of a parent responding to the child's concerns in accordance with CML training.

Following didactics, mothers participated in a series of role-playing exercises in which an undergraduate assistant played the part of a child voicing concerns about terrorism. The undergraduate assistant asked a series of questions about the risks of terrorism (e.g., “Could my school be attacked?”). Mothers were instructed to react to the assistant in accordance with the CML approach just learned. As they role-played, feedback was provided to correct the mother each time she strayed from the CML condition. Following these exercises, mothers were administered a 10-item multiple-choice test to ensure that they were sufficiently prepared. Each test item presented a hypothetical child concern about terrorism; response options reflected potential parental responses. Mothers were instructed to choose the response that best matched the CML condition. If a mother scored ≥80% she was considered ready for the next stage of participation (i.e., trained to criterion). If a mother scored <80%, there was discussion with her about how her incorrect answers did not conform to CML, and an alternate test form was administered. All mothers achieved the 80% criterion on the first attempt.

DAU training

Didactics for DAU entailed a self-administered Power Point presentation about the diversity of parenting styles and parental reactions to content viewed on television, without specifying any in particular as most helpful (a script of the DAU didactic training presentation is available upon request). The presentation was interspersed with a series of video clips of child actors asking questions about the likelihood of future attacks. In DAU, clips did not include an actor playing the part of a parent responding to the child's concerns. Instead, mothers were instructed to consider how they would react if this were their child and to write this down. Instead of completing a trained-to-criterion test, DAU mothers were given 10 min to write down what they tended to do when the topic of terrorism comes up with their child.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Participants did not differ significantly across conditions on age, F(2, 87) = 0.25, p = .78; gender, χ2(2, N = 90) = 1.69, p = .43; ethnicity–race, χ2(4, N = 90) = 5.13, p = .27; or household income, χ2(16, N = 90) = 17.12, p = .38. Means and standard deviations of all measures are presented in Table 1. At T1, conditions did not significantly differ according to any study variables (all ps >.05). To determine the effectiveness of the selected news clip in producing expected elevations in dependent variables (i.e., manipulation check), we analyzed T1 and T2 data via one-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs). The news clip was effective in producing elevations in children's societal terrorism-related threat perception, F(1, 89) = 7.58, p = .01, personal terrorism-related threat perception, F(1, 89) = 25.35, p < .0001, and state anxiety, F(1, 89) = 26.78, p < .0001.

Table 1.

Means (and SDs) of Child and Mother Study Measures

| CMLa |

DAUa |

CML-NDa |

Full sampleb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Tl | T2 | T3 | Tl | T2 | T3 | Tl | T2 | T3 | Tl | T2 | T3 |

| Child | ||||||||||||

| Terror threat, S | 2.9 (2.0) | 2.9 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.9) | 4.2 (1.8) | 3.8 (1.7) | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.9) | 2.8 (1.9) | 3.3 (1.8) | 3.1 (1.7) |

| Terror threat, P | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.8) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.8) | 1.5 (1.5) |

| Hurricane/flood threat, S | 2.8 (1.9) | 3.0 (1.7) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.9) | 3.6 (1.7) | 3.1 (1.9) | 2.4 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.9) | 2.5 (2.0) | 2.7 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.8) |

| Hurricane/flood threat, P | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.4) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.8) | 1.7 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.5) |

| STAIC | 29.1 (4.9) | 31.8 (7.9) | 29.1 (6.8) | 27.0 (4.2) | 32.7 (8.7) | 28.6 (5.1) | 28.5 (3.6) | 32.2 (7.3) | 30.4 (5.9) | 28.2 (4.3) | 32.2 (7.9) | 29.4 (6.0) |

| Mother | ||||||||||||

| Terror threat, S | 32.0 (24.1) | 25.5 (24.7) | 28.5 (25.0) | 49.0 (29.0) | 57.5 (29.0) | 53.0 (29.3) | 37.6 (24.1) | 29.4 (23.7) | 31.9 (28.3) | 39.5 (26.5) | 37.5 (29.3) | 37.8 (29.4) |

| Terror threat, P | 24.3 (23.0) | 14.8 (19.4) | 12.2 (16.9) | 30.6 (28.3) | 36.6 (29.3) | 27.2 (27.8) | 26.2 (25.8) | 15.9 (18.9) | 13.5 (20.3) | 27.0 (25.6) | 22.4 (24.9) | 17.7 (22.9) |

| Hurricane/flood threat, S | 50.1 (30.4) | 40.0 (30.4) | 39.8 (31.5) | 49.5 (23.3) | 54.8 (24.1) | 51.8 (27.4) | 45.4 (28.4) | 39.0 (29.1) | 37.0 (29.1) | 48.3 (27.3) | 44.6 (28.7) | 42.9 (29.8) |

| Hurricane/flood threat, P | 16.7 (18.8) | 11.3 (16.2) | 11.67 (16.8) | 18.6 (21.2) | 27.4 (24.7) | 23.2 (21.8) | 17.5 (21.1) | 13.9 (22.3) | 13.1 (20.7) | 17.5 (21.1) | 17.6 (22.3) | 13.1 (20.7) |

| STAI | 29.1 (7.7) | 32.3 (9.5) | 27.8 (7.6) | 31.3 (8.5) | 42.5 (11.1) | 36.9 (9.3) | 28.2 (9.1) | 31.2 (10.1) | 26.5 (7.2) | 29.5 (8.5) | 35.3 (11.4) | 30.5 (9.3) |

Note. CML = coping and media literacy; DAU = discussion as usual; CML-ND = coping and media literacy-no discussion; Tl = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; S = societal; P = personal; STAIC = State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

n = 30.

N = 90.

CML training manipulation was checked in multiple ways. Testing conducted at the conclusion of CML training indicated that CML mothers were sufficiently trained to criterion (mean score = 99.00%, SD = 4.03). At the conclusion of CML training, mothers were asked to rate the extent to which the CML approach was typical of how they would tend to speak to their child at home about frightening news. Seventy percent of CML mothers indicated that the CML approach was not at all or only somewhat like how they typically would speak to their child at home about frightening news, suggesting that the majority of CML-trained mothers believed the approach to be different from their usual discussion approach at home. Mothers were asked at the conclusion of the study to rate the extent to which they believed that the manner in which they approached the news clip with their child during the discussion period was typical of how they would tend to react at home with their child. Whereas 90% of DAU mothers reported that the approach they took was very much like how they typically would speak to their child at home about frightening news, only 50% of CML mothers reported that the approach they took was very much like how they would speak to their child at home, χ2(2, N = 90) = 16.70, p < .001.

Cohort Effects Check

World events that occurred during the data collection phase of the study (e.g., terrorist attacks) could have exerted an influence upon the measures. Participants’ ID numbers were assigned consecutively and sequentially; participant ID did not correlate with any study variables (all ps > .05), indicating that study findings are not related to external (i.e., nonstudy) events occurring over the time frame of the study.

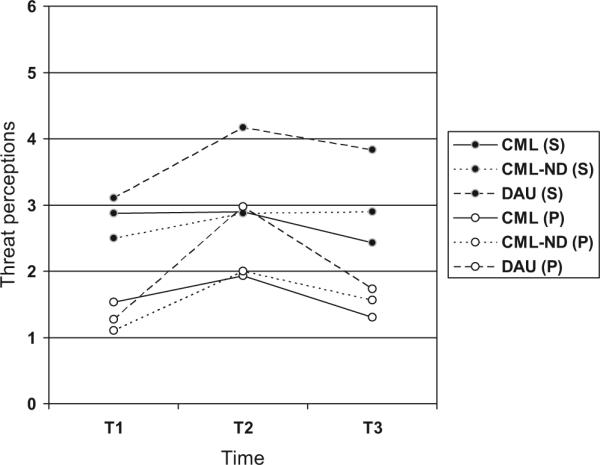

Evaluating CML: Child Outcomes

Two-way mixed ANOVAs examining condition differences across time were conducted. Specifically, we conducted 3 (Time, within-subjects) × 3 (Condition, between-subjects) factorial ANOVAs. Table 2 presents significance tests and effect sizes for time and Time × Condition interactions for each dependent variable. Table 3 presents the details of single degree of freedom contrasts of group differences. To account for multiple comparisons (i.e., three tests per family of tests), a family-wise alpha rate of .017 was applied to all single degree of freedom contrasts. Analyses examining societal terrorism-related threat perception revealed a significant interaction effect, such that the effect of time on societal terrorism-related threat perceptions varied across conditions (see Figure 1). Although societal threat perceptions did not differ across groups at T1, F(2, 87) = 0.78, p > .05, η2 = .02, they did differ across groups at T2, F(2, 87) = 5.59, p < .008, η2 = .11, and at T3, F(2, 87) = 5.52, p < .01, η2 = .11. Applying a family-wise alpha rate of .017, post hoc comparisons (see Table 3) revealed that at T2, DAU youth reported significantly higher societal terrorism-related threat perceptions than both CML and CML-ND youth. CML-ND youth (whose mothers received CML training) did not differ from CML youth at T2. DAU youth continued to report greater societal threat perceptions at T3 than CML youth.

Table 2.

Main and Interactive Effects of Time and Time × Condition

| Time |

Time × Condition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | F | dfs | η2 | F | dfs | η2 |

| Child threat perception | ||||||

| Terrorism, S | 4.38* | 4, 174 | .05 | 2.87* | 4, 174 | .06 |

| Terrorism, P | 17.37*** | 4, 174 | .17 | 2.70* | 4, 174 | .06 |

| Hurricane/flood, S | 1.16 | 2, 174 | .02 | 0.61 | 2, 174 | .01 |

| Hurricane/flood, P | 13.34*** | 2, 174 | .13 | 0.70 | 2, 174 | .02 |

| State anxiety |

20.75*** |

2, 174 |

.19 |

1.24 |

4, 174 |

.03 |

| Mother threat perception | ||||||

| Terrorism, S | 0.62 | 1.8, 157.3 | .01 | 3.56** | 3.6, 157.3 | .08 |

| Terrorism, P | 7.99*** | 1.8, 158.6 | .08 | 2.59* | 3.7, 158.6 | .06 |

| Hurricane/flood, S | 5.37** | 4, 174 | .06 | 4.37** | 4, 174 | .09 |

| Hurricane/flood, P | 0.55 | 2, 174 | .01 | 3.74** | 4, 174 | .08 |

| State anxiety | 29.95*** | 1.8, 158.4 | .26 | 6.46*** | 3.7, 158.4 | .13 |

Note. S = societal; P = personal.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Details of Single Degree of Freedom Contrasts

| Parameter |

SE |

ta |

95% CI (lower, upper) |

η2 |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DV1 | DV2 | DV3 | DV1 | DV2 | DV3 | DV1 | DV2 | DV3 | DV1 | DV2 | DV3 | DV1 | DV2 | DV3 |

| CML vs. DAU at T1 | −0.23 | 0.27 | 2.1 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 1.2 | −0.47 | 0.73 | 1.7 | −1.2, 0.76 | −0.5, 1.0 | −0.3, 4.4 | .00 | .01 | .05 |

| CML vs. CML-ND at T1 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 1.1 | 0.75 | 1.10 | 0.48 | −0.61, 1.3 | −0.35, 1.2 | −1.7, 2.8 | .01 | .02 | .00 |

| DAU vs. CML-ND at T1 | 0.60 | 0.17 | −1.5 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 1.0 | 1.27 | 0.47 | −1.52 | −0.35, 1.5 | −0.54, 0.87 | −3.6, 0.49 | .03 | .00 | .04 |

| CML vs. DAU at T2 | −1.3 | −1.0 | −.87 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 2.1 | −2.8** | −2.3** | −0.41 | −2.2, −0.36 | −1.9, −0.13 | −5.1, 3.4 | .12 | .08 | .00 |

| CML vs. CML-ND at T2 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.37 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 2.0 | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.19 | −0.84, 0.90 | −0.99, 0.85 | −4.2, 3.6 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| DAU vs. CML-ND at T2 | 1.3 | 0.97 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 2.1 | 2.93** | 2.01* | 0.24 | 0.41, 2.2 | 0.01, 1.9 | −0.36, 4.6 | .13 | .07 | .00 |

| CML vs. DAU at T3 | −1.4 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 1.6 | −3.52** | −1.18 | 0.32 | −2.2, −0.60 | −1.2, 0.30 | −2.6, 3.6 | .18 | .02 | .00 |

| CML vs. CML-ND at T3 | −0.47 | −0.27 | −1.3 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 1.6 | −1.09 | −0.71 | −0.79 | −1.3, 0.39 | −1.0, 0.48 | −4.6, 2.0 | .02 | .01 | .01 |

| DAU vs. CML-ND at T3 | 0.93 | 0.17 | −1.8 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 1.4 | 2.04* | 0.43 | −1.27 | 0.02, 1.9 | −0.61, 0.94 | −4.6, 1.0 | .07 | .00 | .03 |

| IC1: T1, T2 × CML, DAU | −1.0 | −1.3 | 2.9 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 2.0 | −2.23** | −2.70** | 1.50 | −1.9, −0.11 | −2.3, −0.34 | −0.99, 6.9 | .08 | .11 | .04 |

| IC2: T1, T2 × CML, CML-ND | −0.33 | −0.50 | 0.90 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 1.7 | −0.93 | −1.07 | 0.52 | −1.1, 0.38 | −1.4, 0.44 | −2.6, 4.4 | .01 | .02 | .00 |

| IC3: T1, T2 × DAU, CML-ND | 0.70 | 0.80 | −2.0 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 2.0 | 1.57 | 1.72 | −1.03 | −0.19, 1.6 | −0.13, 1.7 | −6.0, 1.9 | .04 | .05 | .02 |

| IC4: T2, T3 × CML, DAU | −0.13 | 0.60 | −1.4 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 1.5 | −0.33 | 1.45 | −.94 | −0.95, 0.68 | −0.23, 1.4 | −4.3, 1.5 | .00 | .03 | .02 |

| IC5: T2, T3 × CML, CML-ND | −0.50 | −0.20 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 1.4 | −1.62 | −0.57 | 0.67 | −1.1, 0.12 | −0.91, 0.51 | −1.8, 3.7 | .04 | .01 | .01 |

| IC6: T2, T3 × DAU, CML-ND | −0.37 | −0.80 | 2.3 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 1.5 | −0.97 | −2.06* | 1.53 | −1.1, 0.39 | −1.6, −0.02 | −0.72, 5.3 | .02 | .07 | .04 |

Note. Details of contrasts for hurricane/flood-related threat perceptions and for mother variables are available by request from Jonathan S. Comer. Coping and media literacy-no discussion (CML-ND) mothers received coping and media literacy (CML) training but were not permitted to discuss the clip with their child between Time 2 (T2) and Time 3 (T3). DV1 = terrorism threat perception (societal); DV2 = terrorism threat perception (personal); DV3 = state anxiety; IC = interaction contrast; DAU = discussion as usual; T1 = Time 1.

dfError = 58 for all t tests in table.

p < .05.

p < .017 (alpha-adjusted family-wise error rate).

Figure 1.

Interactions of Time × Condition on children's terrorism-related threat perceptions. Coping and media literacy-no discussion (CMLND) mothers received coping and media literacy (CML) training but were not permitted to discuss the clip with their child between Time 2 (T2) and Time 3 (T3). T1 = Time 1; DAU = discussion as usual; S = societal threat perceptions; P = personal threat perceptions.

Analyses of personal terrorism-related threat perception also showed a significant interaction effect: The effect of time on personal terrorism-related threat perceptions varied across conditions (see Figure 1). Tests revealed that although personal threat perceptions did not differ across groups at T1, F(2, 87) = 0.69, p > .05, η2 = .02, youth threat perceptions did differ across groups at T2, F(2, 87) = 3.11, p < .05, η2 = .07. Post hoc comparisons (see Table 3) revealed that at T2, DAU youth reported higher personal terrorism-related threat perceptions than CML youth. CML-ND youth (whose mothers received CML training) did not differ from CML youth at Time 2. Youth reports of personal threat perceptions did not differ at T3, F(2, 87) = 0.67, p > .05, η2 = .02.

Analyses of child state anxiety showed a significant time effect. Across conditions, youth at T2 had higher state anxiety than youth at T1, F(1, 87) = 26.93, p < .0001, η2 = .23, and youth at T3 had lower state anxiety than at T2, F(1, 87) = 23.11, p < .0001, η2 = .21. Analyses did not show an interaction effect of Time × Condition. Youth across conditions exhibited a significant increase in state anxiety from T1 to T2 and then a significant decrease in state anxiety from T2 to T3.

A main effect for time was found for children's personal, but not societal, hurricane/flood threat perceptions. Across conditions, children's perceptions of personal vulnerability to hurricanes and floods increased from T1 to T2, F(1, 87) = 24.86, p < .001, η2 = .22; perceptions did not change from T2 to T3, F(1, 87) = 3.05, p > .05, η2 = .03. Time × Condition interaction effects were nonsignificant.

Evaluating CML: Mother Outcomes

Mauchly's test indicated that the assumption of sphericity (as is common in repeated-measures analyses) had been violated, χ2(2, N = 90) = 9.00, p < .01 (see Huynh & Mandeville, 1979, for a full discussion on repeated-measures sphericity); therefore, we corrected degrees of freedom for these repeated-measures analyses using Greenhouse–Geisser estimates of sphericity (ε = .91; see Jaccard & Ackerman, 1985, for a discussion on ε-based adjustment procedures). Our analyses of societal terrorism threat perception in mothers revealed a significant interaction, such that the effect of time on maternal societal terrorism-related threat perceptions varied across conditions. Tests revealed that although societal terrorism threat perceptions did not differ in mothers across groups at T1, societal threat perceptions did differ at T2, F(2, 87) = 13.66, p < .001, η2 = .24, and at T3, F(2, 87) = 6.92, p < .01, η2 = .14. Focused contrasts that applied a .017 error rate revealed that at T2, and again at T3, DAU mothers reported higher societal threat perceptions than both CML and CML-ND mothers.

Regarding personal threat perception of mothers, analyses again revealed a significant interaction, such that the effect of time on maternal personal threat perceptions varied across conditions. Tests revealed that although personal terrorism threat perceptions did not differ in mothers across groups at T1, personal threat perceptions did differ at T2, F(2, 87) = 8.53, p < .001, η2 = .16, and at T3, F(2, 87) = 4.25, p < .02, η2 = .09. Focused contrasts that applied a .017 error rate revealed that at T2, DAU mothers reported higher personal terrorism threat perceptions than did both CML and CML-ND mothers. CML-ND mothers (who received CML training) did not differ from CML mothers at T2. At T3, DAU mothers continued to report greater personal terrorism threat perception than CML mothers, but not CML-ND mothers.

Regarding mother state anxiety, Mauchly's test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated, χ2(2, N = 90) = 7.61, p < .05; therefore, degrees of freedom for these repeated-measures analyses had to be corrected using Greenhouse–Geisser estimates of sphericity (ε = .92). Analyses revealed a significant interaction: The effect of time on maternal state anxiety varied across conditions. Tests revealed that, although maternal state anxiety did not differ across groups at T1, F(2, 87) = 1.10, p > .05, η2 = .03, maternal state anxiety did differ across groups at T2, F(2, 87) = 11.18, p < .001, η2 = .20, and at T3, F(2, 86) = 14.82, p < .001, η2 = .26. At T2, DAU mothers reported greater state anxiety than both CML and CML-ND mothers. CML-ND mothers (who received CML training) did not differ from CML mothers at T2. At T3, DAU mothers continued to report greater state anxiety than CML and CML-ND mothers. At T3, CML-ND and CML mother differences were nonsignificant.

Analyses of maternal hurricane/flood threat perceptions showed significant Time × Condition interaction effects for both societal and personal perceptions. Although maternal threat perceptions did not differ across groups at T1, groups differed on personal and societal perceptions at T2, F(2, 87) = 4.91, p < .01, η2 = .10, and F(2, 87) = 3.02, p < .05, η2 = .07, respectively, and on personal perceptions at T3, F(2, 87) = 7.02, p < .05, η2 = .07. At T2, DAU mothers reported higher personal and societal hurricane/flood-related threat perceptions than both CML mothers and CML-ND mothers. At T3, DAU mothers reported higher personal hurricane/flood-related threat perceptions than both CML and CML-ND mothers. CML-ND mothers (who received CML training) did not differ from CML mothers.

Child Age

Analyses examined child age as a continuous predictor of youth response to the news clip (i.e., changes from T1 to T2). In predicting each dependent variable, we controlled (via dummy codings) for the effect of condition. In accordance with analytic conventions offered by Judd, Kenny, and McClelland (2001) for examining predictors of repeated measures, each dependent variable's mean change score was regressed on age, which was centered. In the prediction of the news clip's effect on societal terrorism threat perception, group condition did provide a significant contribution, F(2, 87) = 3.10, p < .05, and child age added a significant contribution, F(3, 86) = 4.32, p < .01; ΔR2 = .07; B = −0.22, SE(B) = 0.09, β = .26, t(87) = −2.54, p < .01. In the prediction of the news clip's effect on personal terrorism threat perception, group condition again provided a significant contribution, F(2, 87) = 3.87, p = .025, but child age did not add a significant contribution, F(3, 86) = 2.61, p > .05; B = −0.04, SE(B) = 0.10, β = −.05, t(84) = −.44, p > .05. In the prediction of the news clip's effect on child state anxiety, condition did not provide a significant contribution, F(2, 87) = 1.26, p > .05. Similarly, child age did not add a significant contribution, F(3, 86) = 0.85, p > .05; B = −0.10, SE(B) = 0.39, β = −.03, t(87) = −.25, p > .05.

Discussion

The present study supports the benefits of training parents in empirically based strategies for addressing terrorism-related news with their children. Children of CML-trained mothers exhibited lower threat perceptions following viewing of the terrorism-related news clip than did children of mothers encouraged to be themselves (i.e., DAU). Whereas previous work documents the role of parents in helping youth cope with portrayals of aggression (Collins et al., 1981; Nathanson, 1999, 2001), the present findings provide evidence of the utility of training parents to help their children cope with threat-related news. The present study also provides evidence of an association between terrorism-related news and youth threat perceptions and state anxiety: Children responded to the news clip with elevated societal threat perceptions, personal threat perceptions, and state anxiety. The present design affords pre- and postclip data and thus builds on previous correlational work in this area (e.g., Hoven et al., 2005; Pfefferbaum et al., 2003; Phillips et al., 2004; Schuster et al., 2001; see also Comer & Kendall, 2007), which cannot rule out the possibility that particular youth seek out more threat-related news (i.e., self-selection bias). Findings also underscore the potency of terrorism-related news, as our analyses showed the news clip to be associated with children's elevated perceptions of personal vulnerability to hurricanes and floods.

Giving mothers strategies for discussing the news with their children helped mothers themselves cope with the news, and training mothers in CML (i.e., CML and CML-ND mothers) resulted in lower maternal threat perceptions and state anxiety following news exposure and a discussion period than did encouraging mothers to be themselves when reacting to the news (i.e., DAU). Of mothers trained in CML, differences were not found between mothers given an opportunity to use CML strategies with their child (i.e., CML) and those not given an opportunity to use CML strategies with their child (i.e., CML-ND). Thus, in addition to helping youth cope, mothers trained to model confidence and to focus on the disproportionate nature of brief news clips coped better with threatening news than did mothers who were not provided with strategies for addressing the news regardless of whether they actually discussed the news with their child.

Immediately following the news clip (i.e., T2), children of CML-trained mothers evidenced lower threat perceptions than did children of DAU mothers. This finding highlights the importance of nonverbal communication in guiding youth reactions to televised news, as there had been no verbal communication between mothers and children by this point. Given that children take their emotional cues from their parents (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001; Izard & Harris, 1995; Kliewer et al., 2006; Zeidner, Matthews, Roberts, & MacCann, 2003), differences between children of CML-trained mothers and children of DAU mothers at T2 may be explained by differences across the groups in observable maternal displays and reactions to the news clip. DAU children may have been more affected by the news clip because their mothers exhibited less calm during the presentation of the clip. CML training emphasized modeling confidence, and as part of CML didactic training mothers were told, “Pay attention to your own emotions, and be aware of what ways . . .you may be communicating to your child that you are anxious.” Mothers were instructed to pay attention to subtle, nonverbal ways in which they might be communicating to their child that they themselves were fearful (e.g., a hand to mouth, a gasp). In addition, media literacy components of CML training may have prepared mothers to think more critically about the news clip, which may in turn have also affected their nonverbal behavior during the clip. Structured behavioral observations of mothers watching threat-related news with their children are needed to determine whether CML-trained mothers behave differently than DAU mothers during newscasts. Future work would also do well to examine youth perceptions of their mothers’ reactions to the news.

Results indicate that the ways in which parents typically react to terrorism-related news with their children are not sufficient in reducing child threat perceptions to levels comparable to those evidenced by children who viewed terrorism-related news with CML-trained parents. Future work is needed to examine the impact of CML-based parent–child discussions on youth who did not view the news clip with their parents.

Age predicted postclip elevations in children's societal threat perception— older children responded with greater elevation in societal threat perception than did younger children. This is consistent with findings that older children are more likely than younger children to comprehend, as well as be frightened by, TV news (Smith & Wilson, 2002). Future work should examine the effects of news on youth within the context of cognitive development. Threat perception requires the ability to mentally represent the future and a capacity to go beyond that which is observable and consider that which is possible (Vasey, Crnic, & Carter, 1994). As age was not related to changes in personal threat perception, it may be that the ability to mentally represent future threat to oneself emerges earlier than the ability to represent future threat to others.

Despite strengths related to the study's experimental design, internal validity, and socioeconomic and racially diverse sample, potential limitations warrant mention. The study used self-reports. Although youth may be as reliable as their parents in reporting their own internal states (e.g., Weems, Zaken, Costa, Cannon, & Watts, 2005), multi-informant (see Comer & Kendall, 2004; De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005) and/or multimodal (e.g., self-reports and physiological data) approaches may have offered more nuanced findings. The present study examined child age, but other factors may be predictive of youth response to terrorism-related news. Child trait anxiety and prior experiences with terrorism and other traumatic events may affect the impact of threat-related news as well as the efficacy of different parenting approaches. The extent to which parents typically process news with their children might also affect the impact of terrorism-related news on youth and the efficacy of different parental approaches to addressing such news. In addition, to afford causal conclusions about the effects of terrorism-related news on youth, there is a need for future work to examine associations between terrorism-related news and children's threat perceptions and anxiety in the context of a manipulation of the type of news clips presented to children (e.g., neighborhood-crime-related clips and neutral clips).

Generalizability to natural settings (e.g., in the home) cannot be assured. DAU mothers spent 60 min reflecting on what they would do if the topic of terrorism were to emerge. This procedure was included so that differences between groups could not be attributed to differences in amount of time mothers spent considering the news and its potential impact. In naturalistic settings, mothers might not spend such time considering their approach to reacting to the news with their child. In addition, to maximize internal validity and to ensure that all children received the same “dose” of news contact during presentation of the clip, dyads were instructed not to speak during the news clip. This, too, may differ from natural settings. In the context of the present experimental design, findings do not speak to children's reactions when parents help children process the material during news broadcasts (a practice recommended by several professional agencies). Future work should include an experimental manipulation in which some dyads are encouraged to talk during the clip and others are prohibited from doing so.

A limited time frame was studied, and long-term follow-up assessments were not included, and the present study did not examine the cumulative effects of repeated news exposure. Comer and Kendall (2007) noted that a substantial proportion of youth are exposed to second-hand terrorism, that is, the ongoing broadcast of threat and alert in which daily social, cultural, and political events and decisions are recast within the threat of future terrorism. Empirical work investigating sensitization and habituation effects is needed to examine the impact of repeated news exposure, and the efficacy of different parental approaches to addressing such repetition. Findings may not generalize to youth in regions marked by more frequent terrorism, and thus research is needed in regions beset by recurrent terrorist attacks (e.g., Iraq, Israel). Future work is also needed to investigate the impact of news pieces about natural disasters, child abductions, and school shootings, as well as the optimal ways for parents to address such news.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a Graduate Student Research Grant awarded to Jonathan S. Comer from Division 53 of the American Psychological Association, by a Presidential Fellowship awarded to Jonathan S. Comer from Temple University, and by National Institutes of Health Grants 59087 and 64484 awarded to Philip C. Kendall. The authors wish to thank Anne Marie Albano, Lauren Alloy, Deborah Drabick, James P. Hambrick, Richard G. Heimberg, Brian P. Marx, and Daniel Romer for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

References

- Barnes LLB, Harp D, Jung WS. Reliability and generalization of scores on the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Education and Psychological Measures. 2002;62:603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM, Dadds MR, Rapee RM. Family treatment of childhood anxiety: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:333–342. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM, Rapee RM, Dadds MR, Ryan S. Family enhancement of cognitive style in anxious and aggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:187–203. doi: 10.1007/BF01441484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Goodman RF. Childhood traumatic grief: An exploration of the construct in children bereaved on September 11. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:248–259. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable News Network [April 28, 2008];Defending America [transcript] 2005 from http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0501/19/se.02.html.

- Collins WA, Sobol BL, Westby S. Effects of adult commentary on children's comprehension and inferences about a televised aggressive portrayal. Child Development. 1981;52:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Kendall PC. A symptom-level examination of parent-child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:878–886. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000125092.35109.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Kendall PC. Terrorism: The psychological impact on youth. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2007;14:179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Barrett PM, Rapee RM, Ryan S. Family process and child anxiety and aggression: An observational analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:715–734. doi: 10.1007/BF01664736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daleiden EL, Vasey MW. An information-processing perspective on childhood anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17:407–429. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish T, Taghavi R, Neshat-Doost H, Moradi A, Yule W, Canterbury R. Information processing in clinically depressed and anxious children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for future study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, et al. Mother's emotional expressivity and children's behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children's regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP. Is conditioning a useful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:857–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, Walsh DA. A normative study of family media habits. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23:157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbner G, Gross L. Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication. 1976;26:173–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1976.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, Signorielli N. Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, editors. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gerull FC, Rapee RM. Mother knows best: Effects of maternal modeling on the acquisition of fear and avoidance behaviour in toddlers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:279–287. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Lucas CP, Wu P, Mandell DJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Psychopathology among New York City public school children 6 months after September 11. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:545–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard B, Chu BC, Krain AL, Marrs-Garcia AL, Kendall PC. Cognitive-behavioral family therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual. 2nd ed. Workbook Publishing; Ardmore, PA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh H, Mandeville GK. Validity conditions in repeated measures designs. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:964–973. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Harris P. Emotional development and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 1. Theory and methods. Wiley; New York: 1995. pp. 467–503. [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Ackerman L. Repeated measures analysis of means in clinical research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA, McClelland GH. Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-subject designs. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:115–134. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Finch AJ, Auerbach SM, Hooke, Mikulka PJ. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: A systematic evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1976;44:406–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.44.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Parrish KA, Taylor KW, Jackson K, Walker JM, Shivy VA. Socialization of coping with community violence: Influences of caregiver coaching, modeling, and family context. Child Development. 2006;77:605–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klite P, Bardwell RA, Salzman J. Local TV news: Getting away with murder. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics. 1997;2:102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnic JA, Anand SN, Hartl SP. Psychosocial predictors of heavy television viewing among preadolescents and adolescents. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2003;25:87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kubey R, Csikszentmihalyi M. Television and the quality of life: How viewing shapes everyday experience. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM. Understanding the psychological impact of terrorism on youth: Moving beyond posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2007;14:219–223. [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK. Children and adolescents, disasters and terrorism. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. pp. 356–382. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies RG, Clarke JC. The etiology of childhood water phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:499–501. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90131-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M, Shanahan J. Two decades of cultivation research: An appraisal and a meta-analysis. Communication Yearbook. 1997;20:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Steerneman P, Merckelbach H, Meesters C. The role of parental fearfulness and modeling in children's fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:265–268. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacos BL. The terrorist calculus behind 9−11: A model for future terrorism? Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. 2003;26:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Identifying and explaining the relationship between parental mediation and children's aggression. Communication Research. 1999;26:124–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI. Factual and evaluative approaches to modifying children's responses to violent television. Journal of Communication. 2001;54:331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ. Origins of childhood fears: An evaluation of Rachman's theory of fear acquisition. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1991;29:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(91)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M, Henin A, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Pollack MH, Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms following media exposure to tragic events: Impact of 9/11 on children at risk for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:888–902. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, Nixon S, Krug R, Tivis R, Moore V, Brown J, et al. Clinical needs assessment of middle and high school students following the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1069–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, Seale TW, Brandt EN, Pfefferbaum RL, Doughty DE, Rainwater SM. Media exposure in children one hundred miles from a terrorist bombing. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;15:1–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1023293824492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D, Prince S, Schiebelhut L. Elementary school children's responses 3 months after the September 11 terrorist attacks: A study in Washington, DC. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:509–528. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DF, Henriksen L, Foehr UG. Adolescents and media. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2nd ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. pp. 487–521. [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Jamieson KH, Aday S. Television news and the cultivation of fear of crime. Journal of Communication. 2003;53:88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1507–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Ollendick TH. Evidence-based assessment of anxiety and its disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:380–411. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Rabian B. Rating scales for anxiety and mood disorders. In: Shaffer D, Lucas CP, Richters JE, editors. Diagnostic assessment in child and adolescent psychopathology. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 127–166. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SJ, Wilson BJ. Children's comprehension of and fear reactions to television news. Media Psychology. 2002;4:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. STAI manual. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- St. Peters M, Fitch M, Huston AC, Wright JC, Eakins DJ. Television and families: What do young children watch with their parents? Child Development. 1991;62:1409–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of State [April 28, 2008];Country Reports on Terrorism 2004. 2005 from http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/45313.pdf.

- Vasey MW, Crnic KA, Carter WG. Worry in childhood: A developmental perspective. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1994;18:529–549. [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Zaken AH, Costa NM, Cannon MF, Watts SE. Physiological response and childhood anxiety: Association with symptoms of anxiety disorders and cognitive bias. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:712–723. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windschitl PD, Weber EU. The interpretation of “likely” depends on the context, but “70%” is 70%—right? The influence of associative processes on perceived certainty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1999;25:1514–1533. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.6.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidner M, Matthews G, Roberts RD, MacCann C. Development of emotional intelligence: Towards a multi-level investment model. Human Development. 2003;46:69–96. [Google Scholar]