Abstract

Background: Several genome-wide association studies have identified novel loci (KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB) that are associated with HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Of the environmental factors that determine HDL cholesterol, high-carbohydrate diets have been shown to be associated with low concentrations.

Objective: The objective was to evaluate the associations of 8 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located within the KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB loci with lipids and their potential interactions with dietary carbohydrates.

Design: KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB SNPs were genotyped in 920 subjects (441 men and 479 women) who participated in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study. Biochemical measurements were made by using standard procedures. Dietary intakes were estimated by using a validated questionnaire.

Results: For the SNPs KCTD10_i5642G→C and MVK_S52NG→A, homozygotes for the major alleles (G) had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations than did carriers of the minor alleles (P = 0.005 and P = 0.019, respectively). For the SNP 12inter_108466061A→G, homozygotes for the minor allele (G) had higher total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol concentrations than did AG subjects (P = 0.030 and P = 0.034, respectively). Conversely, homozygotes for the major allele (G) at MMAB_3U3527G→C had higher LDL-cholesterol concentrations than did carriers of the minor allele (P = 0.034). Significant gene-diet interactions for HDL cholesterol were found (P < 0.001–0.038), in which GG subjects at SNPs KCTD10_i5642G→C and MMAB_3U3527G→C and C allele carriers at SNP KCTD10_V206VT→C had lower concentrations only if they consumed diets with a high carbohydrate content (P < 0.001–0.011).

Conclusion: These findings suggest that the KCTD10 (V206VT→C and i5642G→C) and MMAB_3U3527G→C variants may contribute to the variation in HDL-cholesterol concentrations, particularly in subjects with high carbohydrate intakes.

INTRODUCTION

Low concentrations of HDL cholesterol have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) (1). Of the environmental factors that determine plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations, high-carbohydrate diets have been shown to be associated with lower concentrations (2–4). However, not all individuals exposed to similar environmental factors have low HDL-cholesterol concentrations, reinforcing the possibility that variation in genetic susceptibility may influence HDL-cholesterol concentrations. In this regard, family and twin studies have shown that 50% of the variation in HDL-cholesterol concentrations is genetically determined (5, 6). Therefore, the variation in HDL cholesterol depends on the joint action of genetic and environmental factors and their interaction.

Recent genome-wide association analyses (GWAS) have discovered novel loci at chromosome 12q24, which includes the genes MVK (murine mevalonate kinase), MMAB [methylmalonic aciduria (cobalamin deficiency) cbIB type], and KCTD10 (potassium channel tetramerization domain-containing 10), all of which influence HDL-cholesterol concentrations (7, 8). The importance of this region in influencing lipid concentrations has also been reported by other linkage studies (9–11). In particular, 2 neighboring genes—MVK and MMAB—participate in metabolic pathways associated with HDL metabolism (12). Mevalonate kinase, encoded by MVK, catalyzes an early step in cholesterol biosynthesis. In humans, homozygosity for milder MVK mutations produces hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome, which is characterized by fever and increased concentrations of immunoglobulins D and A. In agreement with GWAS findings (7, 8), patients with hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome have low HDL-cholesterol concentrations. In humans, deficiency of cob(I)alamin adenosyltransferase, an enzyme encoded by MMAB, results in methylmalonic aciduria (13). Although the role of MMAB in cholesterol metabolism remains unclear, one study showed a negative correlation between urinary methylmalonic acid and red blood cell membrane cholesterol concentrations in patients with schizophrenia (14). In close proximity to the MVK and MMAB genes, the KCTD10 gene has been shown to have membership in a gene network perturbed by loci contributing to the susceptibility of obesity, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (15). Because there remains some discrepancy about which genes direct the associations with HDL-cholesterol concentrations, it is important to assess the association of different markers, each of which represents distinct regions of linkage disequilibrium (LD).

Only one of the previous studies that examined this chromosomal region with chosen variants has investigated the effects of MVK_S52NG→A polymorphism on HDL-cholesterol concentrations (16), but the contribution of dietary components was not assessed. Furthermore, diet was not considered in the GWAs described above (7, 8). Therefore, the aims of the present study were first to assess the association of several polymorphisms at the KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB genes with lipids, particularly with HDL cholesterol. Second, we investigated whether these genetic variants interact with dietary carbohydrates to modulate HDL-cholesterol concentrations.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study population (n = 920) consisted of 441 men and 479 women aged 49 ± 16 y who participated in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study. Participants were recruited from 3-generational pedigrees from 2 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study field centers (Minneapolis, MN, and Salt Lake City, UT) (17). The study population was homogeneous with regard to ethnic background, ie, all individuals were of European origin. The detailed design and methodology of the study were described previously (18). The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Alabama, the University of Minnesota, the University of Utah, and Tufts University. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Data collection

For GOLDN participants, clinical examinations at the baseline visit included anthropometric and blood pressure (BP) measurements. Weight was measured with a beam balance and height with a fixed stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kg) divided by the square of height (in m). BP was measured twice with an oscillometric device (Dinamap Pro Series 100; GE Medical Systems Information Technologies and Critikon Company, LLC, Tampa, FL) while the subjects were seated after having rested for 5 min. Reported systolic and diastolic BP values were the mean of 2 measurements. Questionnaires were administered to assess demographic and lifestyle information, medical history, and medication use. Physical activity was considered starting from an activity 2 times/wk during a minimum of 2 h.

Habitual dietary food intake was assessed by using the Diet History Questionnaire developed by the National Cancer Institute (19). It consists of 124 food items and included portion size and dietary supplement questions. Two studies have confirmed its validity (20, 21).

Laboratory methods

Blood samples were drawn after the subjects had fasted overnight. Fasting glucose was measured by using a hexokinase-mediated reaction, and total cholesterol was measured by using a cholesterol esterase cholesterol oxidase reaction on a Hitachi 911 autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The same reaction was used to measure HDL cholesterol after precipitation of non-HDL cholesterol with magnesium/dextran. LDL cholesterol was measured by using a homogeneous direct method (LDL Direct Liquid Select Cholesterol Reagent; Equal Diagnostics, Exton, PA). Triglycerides were measured with a glycerol-blanked enzymatic method on the Roche COBAS FARA centrifugal analyzer (Roche Diagnostics).

Genetic analyses

DNA was extracted from blood samples and purified by using commercial Puregene reagents (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer's instructions. Eight single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB loci (KCTD10_V206VT→C, rs2302706; KCTD10_i5642G→C, rs10850219; 12inter_108466061A→G, rs731178; MMAB_3U3527G→C, rs2241201; MVK_m751T→C, rs12314392; MVK_i851G→T, rs3759387; MVK_S52NG→A, rs7957619; and 12inter_108521796T→G, rs9888325) were genotyped. SNPs were selected on the basis of 2 criteria: bioinformatics functional assessment (18) and LD structure. Assessment of the LD structure at the KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB loci with the use of data from the CEU (western European ancestry) population facilitated the selection of tag SNPs representing different LD blocks using an inclusion criterion of r2 > 0.8. Intronic SNPs were also analyzed with MAPPER (22) to uncover potential allele-specific transcription factor binding sites and were manually checked for altered mRNA splice donor and acceptor sites and transversions affecting the poly-pyrimidine tract near splice acceptors. Genotyping was performed by using TaqMan assays with allele-specific probes on the ABIPrism 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to routine laboratory protocols (23). (See Supplemental Table 1 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for a description of SNPs and ABI assay-on-demand ID identifiers.) The pairwise LD between SNPs was estimated as a correlation coefficient (R) in unrelated subjects by using the Helixtree software package (Golden Helix Inc, Bozeman, MT).

Statistical analyses

SPSS software (version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analyses. Differences in mean values were assessed by using analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni to test for group differences. Categorical variables were compared by using Pearson's chi-square or the Fisher's exact tests. Potential confounding factors were age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking habit (current compared with never and past smokers), alcohol consumption (current compared with never and past drinkers), medication use (treatment of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia and hormone treatment by women), prior CHD, and family relationships. Potential interactions between polymorphisms and dietary carbohydrates for HDL-cholesterol concentrations (as continuous variables) were tested by using the analysis of variance after further adjustment for total energy intake (in kcal). Corrections for multiple comparisons were made by using the Bonferroni technique so that P values were multiplied by the number of analyses performed. As a measure of the goodness-of-fit of the models, the square of the correlation coefficient among macronutrients was calculated. We further adjusted the models for intakes of saturated fat, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and protein (as continuous variables). Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as means ± SDs for continuous variables and as frequencies or percentages for categorical variables.

RESULTS

Compared with women, men had higher systolic and diastolic BP measurements. As expected, HDL-cholesterol concentrations were lower in men than in women, whereas triglycerides were higher in men. Men had a higher prevalence of CHD and were more likely to receive treatment for hyperlipidemia than were women. No significant differences in other variables were observed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and biochemical characteristics of men and women in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study (n = 920)

| Men (n = 441) | Women (n = 479) | P | |

| Age (y) | 49 ± 161 | 49 ± 16 | 0.8142 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6 ± 4.8 | 28.3 ± 6.4 | 0.3142 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 119 ± 14.9 | 113 ± 197.9 | <0.0012 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 71 ± 8.9 | 66 ± 9.1 | <0.0012 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.95 ± 0.99 | 5.00 ± 1.07 | 0.4352 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.22 ± 0.78 | 3.13 ± 0.86 | 0.0692 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.07 ± 0.25 | 1.35 ± 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.68 ± 0.91 | 1.40 ± 0.81 | 0.0012 |

| Current smokers [n (%)] | 37 (8) | 41 (9) | 0.9183 |

| Current alcohol drinkers [n (%)] | 219 (50) | 229 (48) | 0.6443 |

| Treatment of diabetes [n (%)] | 20 (5) | 23 (5) | 0.8773 |

| Treatment of hypertension [n (%)] | 87 (20) | 80 (17) | 0.2663 |

| Treatment to lower lipids [n (%)] | 24 (5) | 13 (3) | 0.0433 |

| Hormone treatment [n (%)] | — | 96 (20) | <0.0013 |

| Prior coronary heart disease [n (%)] | 43 (10) | 11 (2) | <0.0013 |

Mean ± SD (all such values).

ANOVA.

Chi-square test.

For all studied polymorphisms, there was no departure from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.05). (See Supplemental Table 2 under “Supplemental data” in the online issue for a presentation of the pairwise LD estimates expressed as correlation coefficients for all 8 SNPs.) Given that the SNP 12inter_108466061A→G was in strong LD (>0.9) with 12inter_108521796T→G, the latter SNP was excluded from further analyses. Because of the low genotype frequencies of homozygotes for the minor alleles, we analyzed 5 SNPs (KCTD10_V206VT→C, KCTD10_i5642G→C, MMAB_3U3527G→C, MVK_i851G→T, and MVK_S52NG→A) using 2 genotype categories (dominant model). The other 2 SNPs were analyzed by using 3 genotype categories (additive model). Considering the homogeneity between sex-specific genotype groups, men and women were pooled together for subsequent analyses.

For the SNPs KCTD10_i5642G→C and MVK_S52NG→A, homozygotes for the major allele (G) had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations than did carriers of the minor alleles (P = 0.005 and P = 0.019, respectively) (Table 2). After Bonferroni correction, homozygotes for the i5642G allele still had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations (P = 0.015), whereas differences between genotypes were marginally significant for the SNP MVK_S52NG→A (P = 0.057). For the SNP 12inter_108466061A→G, homozygotes for the minor allele (G) had higher total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol concentrations than did AG subjects (P = 0.024 and P = 0.029, respectively), whereas no significant differences for these variables were found in homozygotes for the major allele (A) (P > 0.2 for both). For SNP MMAB_3U3527G→C, homozygotes for the major allele (G) had higher LDL-cholesterol concentrations than did those carriers of the minor allele (P = 0.034). No other significant associations were found between these studied SNPs and lipids. These differences between genotypes were no longer significant after Bonferroni correction for total cholesterol (P = 0.090) and LDL cholesterol (P = 0.102) (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms and fasting lipid profiles in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study population (n = 920)1

| TT | TC + CC | GG | GC + CC | AA | AG | TC | CC | GT + TT | AA + AG | P | |

| KCTD10_V206VT→C | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.96 ± 0.01(634) | 5.01 ± 0.05 (286) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.488 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.16 ± 0.02 (634) | 3.21 ± 0.04 (286) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.348 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.22 ± 0.01 (634) | 1.22 ± 0.01 (286) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.954 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.57 ± 0.04 (634) | 1.45 ± 0.07 (286) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.185 |

| KCTD10_i5642G→C | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 4.98 ± 0.03 (599) | 4.97 ± 0.05 (321) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.820 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 3.18 ± 0.03 (599) | 3.16 ± 0.04 (321) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.633 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.20 ± 0.01 (599) | 1.26 ± 0.01 (321) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.005 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.55 ± 0.04 (599) | 1.50 ± 0.06 (321) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.602 |

| 12inter_108466061A→G | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 5.12 ± 0.06 (209)2 | — | 4.97 ± 0.06 (217) | 4.92 ± 0.04 (494) | — | — | — | — | 0.030 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 3.29 ± 0.05 (209)2 | — | 3.16 ± 0.05 (217) | 3.13 ± 0.03 (494) | — | — | — | — | 0.034 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.19 ± 0.02 (209) | — | 1.23 ± 0.01 (217) | 1.22 ± 0.01 (494) | — | — | — | — | 0.254 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.64 ± 0.08 (209) | — | 1.53 ± 0.08 (217) | 1.49 ± 0.05 (494) | — | — | — | — | 0.304 |

| MMAB_3U3527G→C | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 5.03 ± 0.04 (482) | 4.92 ± 0.04 (438) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.075 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 3.22 ± 0.03 (482) | 3.12 ± 0.03 (438) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.034 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.21 ± 0.01 (482) | 1.23 ± 0.01 (438) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.342 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.59 ± 0.05 (482) | 1.47 ± 0.05 (438) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.161 |

| MVK_m751T→C | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.02 ± 0.05 (312) | — | — | — | — | — | 4.93 ± 0.04 (441) | 5.02 ± 0.07 (167) | — | — | 0.406 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.19 ± 0.04 (312) | — | — | — | — | — | 3.14 ± 0.03 (441) | 3.22 ± 0.05 (167) | — | — | 0.468 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.21 ± 0.01 (312) | — | — | — | — | — | 1.23 ± 0.01 (441) | 1.21 ± 0.02 (167) | — | — | 0.556 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.60 ± 0.06 (312) | — | — | — | — | — | 1.49 ± 0.05 (441) | 1.52 ± 0.09 (167) | — | — | 0.476 |

| MVK_i851G→T | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 5.00 ± 0.04 (513) | — | — | — | — | — | 4.94 ± 0.04 (407) | — | 0.327 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 3.20 ± 0.03 (513) | — | — | — | — | — | 3.14 ± 0.03 (407) | — | 0.282 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.21 ± 0.01 (513) | — | — | — | — | — | 1.23 ± 0.01 (407) | — | 0.452 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.52 ± 0.05 (513) | — | — | — | — | — | 1.55 ± 0.06 (407) | — | 0.672 |

| MVK_S52NG→A | |||||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 4.98 ± 0.03 (725) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4.97 ± 0.06 (195) | 0.898 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 3.19 ± 0.02 (725) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3.12 ± 0.05 (195) | 0.287 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.21 ± 0.01 (725) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.26 ± 0.02 (195) | 0.019 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | — | — | 1.54 ± 0.04 (725) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.52 ± 0.08 (195) | 0.894 |

All values are means ± SEs; n in parentheses. Differences in mean values were assessed by ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons. Multivariate P values were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking habit, alcohol consumption, medication use, prior coronary heart disease, and family relationships.

Significantly different from AG, P < 0.05 (Bonferroni post hoc test).

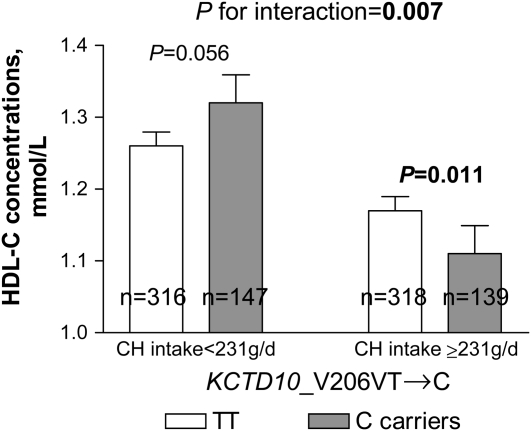

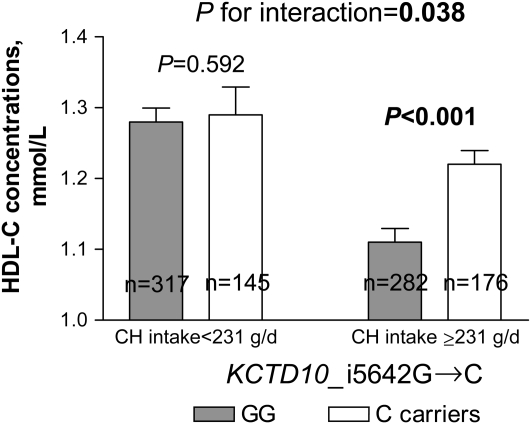

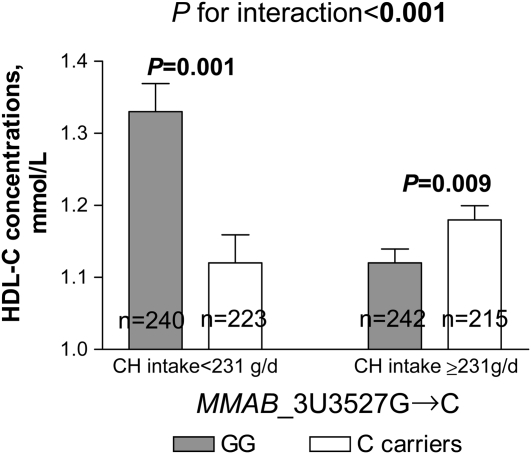

We next examined whether associations between SNPs and HDL-cholesterol concentrations were related to carbohydrate intake in this population. Because there were no significant differences in dietary intake according to genotype groups (data not shown), we investigated whether interactions between carbohydrate intake and genes (KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB) could modulate the observed associations with HDL-cholesterol concentrations. We dichotomized carbohydrate intake according to the median value (<231 compared with ≥231 g/d). A significant gene-diet interaction was found (P = 0.007); carriers of the C allele at SNP KCTD10_V206VT→C who consumed diets containing high amounts of carbohydrate had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations than did subjects homozygous for the T allele (P = 0.011), whereas a trend toward higher concentrations was observed in carriers of the C allele who consumed diets with low amounts of carbohydrate (P = 0.056) (Figure 1). A significant gene-diet interaction was also observed for the SNP KCTD10_i5642G→C (P = 0.038); GG subjects who consumed diets with high amounts of carbohydrate had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations than did carriers of the C allele (P < 0.001). However, no significant differences based on genotype were found among subjects who consumed diets with low amounts of carbohydrate (P > 0.5) (Figure 2). Finally, a significant gene-diet interaction was observed for the SNP MMAB_3U3527G→C (P < 0.001); GG subjects consuming diets with low amounts of carbohydrate had higher HDL-cholesterol concentrations than did carriers of the C allele (P = 0.001), whereas lower concentrations were seen in GG subjects who consumed diets with high amounts of carbohydrate (P = 0.009) (Figure 3). Because the carbohydrate intake was highly correlated with intakes from saturated fat, MUFAs, PUFAs, and protein (r = 0.752−0.841, P < 0.001), models were additionally adjusted for these nutrients. Further adjustment for these nutrients had little effect on gene-diet interactions for the SNPs MMAB_3U3527G→C and KCTD10_V206VT→C (P < 0.001 and P = 0.001, respectively), whereas these interactions were slightly stronger for the SNP KCTD10_i5642G→C (P = 0.033). A marginally significant gene-diet interaction was found for the SNP MVK_S52NG→A (P = 0.055); subjects homozygous for the S52NG allele had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations only if they consumed diets with high amounts of carbohydrate (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

Mean (±SE) effect of KCTD10_V206VT→C genotype on HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations by carbohydrate (CH) intake in Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study participants (n = 920). P values were adjusted by ANOVA.

FIGURE 2.

Mean (±SE) effect of KCTD10_i5642G→C genotype on HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations by carbohydrate (CH) intake in Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study participants (n = 920). P values were adjusted by ANOVA.

FIGURE 3.

Mean (±SE) effect of MMAB_3U3527G→C genotype on HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations by carbohydrate (CH) intake in Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study participants (n = 920). P values were adjusted by ANOVA.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted HDL-cholesterol concentrations by KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB loci and carbohydrate intake in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) Study population (n = 920)1

| Polymorphism | Carbohydrate intake <231 g/d | P | Carbohydrate intake ≥231 g/d | P | P for interaction |

| mmol/L | mmol/L | ||||

| 12inter_108466061A→G | |||||

| AA (n = 217) | 1.30 ± 0.03 | 0.051 | 1.17 ± 0.02 | 0.569 | 0.104 |

| AG (n = 494) | 1.30 ± 0.01 | 1.14 ± 0.01 | |||

| GG (n = 209) | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | |||

| MVK_m751T→C | |||||

| TT (n = 312) | 1.26 ± 0.02 | 0.342 | 1.15 ± 0.02 | 0.925 | 0.690 |

| TC (n = 441) | 1.30 ± 0.02 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | |||

| CC (n = 167) | 1.27 ± 0.03 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | |||

| MVK_i851G→T | |||||

| GG (n = 513) | 1.29 ± 0.01 | 0.640 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | 0.034 | 0.124 |

| T carriers (n = 407) | 1.27 ± 0.02 | 1.18 ± 0.01 | |||

| MVK_S52NG→A | |||||

| GG (n = 725) | 1.28 ± 0.03 | 0.811 | 1.13 ± 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.055 |

| A carriers (n = 195) | 1.29 ± 0.03 | 1.24 ± 0.02 |

All values are means ± SEs. Differences in mean values were assessed by ANOVA. Multivariate P values were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, physical activity, smoking habit, alcohol consumption, medication use, prior coronary heart disease, family relationships, and total energy intake.

DISCUSSION

This study provides the first evidence that genetic variation at KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB genes modulates plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations depending on dietary carbohydrates. Results indicate that homozygotes for major alleles at SNPs KCTD10_i5642G→C, MMAB_3U3527G→C and MVK (i851G→T and S52NG→A) displayed lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations than carriers of the minor alleles, only if they consumed diets rich in carbohydrates. A significant gene-diet interaction was observed for SNP KCTD10_V206VT→C; carriers of the minor allele showed lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations than did homozygotes for the major allele, only in subjects who consumed diets high in carbohydrates. Therefore, homozygotes for major alleles at these SNPs and carriers of the 206V allele showed an interaction with dietary carbohydrates, which lowers plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations, whereas carriers of the minor alleles and homozygotes for the V206 allele were resistant to carbohydrate-induced decreases in HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Overall, these findings suggest that dietary habits may modulate the contributions of KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB polymorphisms to the genetic susceptibility toward lowering HDL-cholesterol concentrations.

Significant associations were found between the SNPs 12inter_108466061A→G and MMAB_3U3527G→C and LDL-cholesterol concentrations. However, these associations were stronger for HDL-cholesterol concentrations; homozygotes for the major alleles at the SNPs KCTD10_i5642G→C and MVK_252NG→A had lower concentrations.

The MVK gene, which encodes the catalyst of an early step in cholesterol biosynthesis, has been implicated to affect HDL-cholesterol concentrations in 2 recent GWAS (7, 8), which supports our findings. However, others found no significant associations between the MVK_S52NG→A SNP and HDL-cholesterol concentrations (16). These discrepancies may be due to differences in age, HDL-cholesterol concentrations, and lifestyle (particularly smoking habit) across populations. In contrast, deficiency of cob(I)alamin adenosyltranferase, an enzyme encoded by MMAB, results in methylmalonic aciduria. Interestingly, a negative correlation between urinary methylmalonic acid and red blood cell membrane cholesterol concentrations was found in patients with schizophrenia (14). Consistently, we observed a significant association between MMAB_3U3527G→C and LDL-cholesterol concentrations. Although the role of MMAB in cholesterol metabolism is not well understood, its involvement in cholesterol synthesis through SREBP2 (24) may explain our findings. However, the exact functions of MVK and MMAB in lipid metabolism need to be clarified in future studies, which may reveal their potential as targets for intervention.

Murine Kctd10 has been implicated in a metabolic network significantly associated with a complex of linked genetic loci related to obesity-, diabetes-, and atherosclerosis-associated traits (15). In this study, coexpression networks were constructed from gene activity data derived from liver and adipose tissue collected from a segregating mouse population and identified several subnetworks associated with metabolic traits. Particularly, Kctd10 was included in a network enriched for expression traits supported as causal for ≥1 of the following 6 metabolic traits: abdominal fat mass, weight, plasma insulin concentrations, free fatty acids, total plasma cholesterol concentrations, and aortic lesion size. Therefore, by extension, the involvement of human KCTD10 in this metabolic network coupled with our results supports its association with HDL-cholesterol concentrations.

Importantly, this is the first study to show an interaction between novel variants at the KCTD10 and MMAB genes with carbohydrate intake. The mechanism by which these polymorphisms may contribute to the observed interactions is unknown. Given that 3 of the analyzed SNPs map to noncoding regions and are members of large LD blocks, the likelihood that these SNPs represent a functional mutation is low. However, the presence of transcriptional enhancers and other regulatory elements, observed frequently in intronic regions (25), could explain our findings. Interestingly, Dixon et al (26) reported that the KCTD10_V206VT→C SNP was associated with KCTD10 mRNA concentrations in a white population. In particular, the minor allele (C) was associated with higher expression. Although no significant associations were found between this SNP and lipids, we found a significant gene-diet interaction; carriers of the 206V allele had lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations only if they had higher intakes of carbohydrates. This gene-diet interaction may have an important influence on regulation of KCTD10 expression. Therefore, it is plausible that carriers of the minor allele may be better suited to sensing levels of dietary carbohydrate and exhibit increased expression of KCTD10 and, accordingly, lower HDL-cholesterol concentrations.

It is well-established that diets higher in carbohydrates are associated with low HDL-cholesterol concentrations (4–6), elevated postprandial glucose and insulin concentrations, and decreased insulin sensitivity (27). Moreover, diets rich in carbohydrates are associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis through the insulin-mediated activation of the renin-angiotensin system, growth factors, and cytokines (28). Overall, our data support a synergistic relation between genes and diet by which tailored dietary recommendations targeted at increasing HDL-cholesterol concentrations may modulate the genetic expression of several KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB genetic variants. The potential mechanisms that underlie these gene-diet interactions may include dietary influences on HDL production and transport rates and catabolic processes. Of note, compared with dietary interventions, similar increases in HDL-cholesterol concentrations have been reported in patients with low HDL-cholesterol concentrations after drug therapy (5–20%). Therefore, the present study provides proof-of-concept for the potential application of genetics in the context of personalized nutritional recommendations for cardiovascular disease prevention (29).

Despite the evidence, our data should be interpreted with caution. The cross-sectional design of this study may weaken or distort any true relation between KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB and carbohydrate intakes. In this regard, large prospective studies with a long period of follow-up are required to clarify the directionality of these associations. Because carbohydrate intake is only part of a larger landscape of dietary intake, we further adjusted for intake of other macronutrients. Although these adjustments had little effect on the results, this adjustment was likely incomplete because of residual confounding by imprecisely measured dietary factors. The exploratory nature of the present study and the large number of comparisons necessitates further studies in other larger populations and ethnic groups, particularly those with low HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Consideration of the variability of minor allele frequencies of the examined SNPs compared with those reported from other populations with different ethnic backgrounds likely will reveal variants exerting a greater effect on HDL-cholesterol concentrations and/or a greater susceptibility to interactions with environmental factors. According to HapMap data, minor allele frequencies (MAFs) in our study population are higher for the 7 SNPs with data than for those reported in Chinese and Japanese populations and similar to those observed in Europeans. The Yoruba population from Africa presents MAFs similar to or greater than MAFs in our population. For example, the minor A allele of rs3759387 shows MAFs of 24% in European, 44% in African, and 15–17% in Asian populations, respectively.

In conclusion, the present study showed an interaction between novel variants in KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB genes and carbohydrate intake on plasma HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Understanding the effects of these polymorphisms on HDL cholesterol could help to modulate the risk of atherosclerosis in the general population, particularly in subjects consuming diets with a high carbohydrate content. Moreover, recognition of these gene-diet interactions offers the potential to identify lifestyle changes which, when implemented, may obviate the risk of CHD associated with specific KCTD10, MVK, and MMAB genetic variants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors' responsibilities were as follows—DKA and JMO: conception and design of the study; MYT, Y-CL, LDP, and MJ: provision of biochemical phenotypes and genotypes; MJ: collection and assembly of data; MJ, LDP, and JMO: analysis and interpretation of the data; EKK, IB, RJS, PA, and MP: statistical expertise; JMO, LDP, and MJ: writing of the manuscript draft; RJS, DKA, EKK, PA, C-QL, LDP, CES, and Y-CL: critical review of the manuscript; and DKA, JMO, and MJ: funding. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Castelli WP, Garrison RJ, Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Kalousdian S, Kannel WB. Incidence of coronary heart disease and lipoprotein cholesterol levels. The Framingham Study. JAMA 1986;256:2835–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Liu S. Glycemic index and serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration among US adults. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:572–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Y, Li Y, Chiriboga DE, et al. Association between carbohydrate intake and serum lipids. J Am Coll Nutr 2006;2:155–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culberson A, Kafai MR, Ganji V. Glycemic load is associated with HDL cholesterol but not with other components and prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Int Arch Med 2009;2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrap SB, Wong ZY, Scurrah KJ, Lamantia A. Genome-wide linkage analysis of population variation in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Hum Genet 2006;119:541–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goode EL, Cherny SS, Christian JC, et al. Heritability of longitudinal measures of body mass index and lipid and lipoprotein levels in aging twins. Twin Res Hum Genet 2007;10:703–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 2008;40:161–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet 2009;41:56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feitosa ME, Rice T, Borecki IB, et al. Pleiotropic QTL on chromosome 12q23-q24 influences triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: the HERITAGE family study. Hum Biol 2006;78:317–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosse Y, Chagnon YC, Despres JP, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan reveals multiple susceptibility loci influencing lipid and lipoprotein levels in the Quebec Family Study. J Lipid Res 2004;45:419–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch CL, Xia YR, Shechter I, et al. Genetic regulation of cholesterol homeostasis: chromosomal organization of candidate genes. J Lipid Res 1996;37:1406–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holleboom AG, Vergeer M, Hovingh GK, Kastelein JJP, Kuivenhoven JA. The value of HDL genetics. Curr Opin Lipidol 2008;19:385–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobson CM, Wai T, Leclerc D, et al. Identification of the gene responsible for the cbIB complementation group of vitamin B12-dependent methylmalonic aciduria. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11:3361–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozcan O, Ipcioglu OM, Gultepe M, Basogglu C. Altered red cell membrane compositions related to functional vitamin B(12) deficiency manifested by elevated urine methylmalonic acid concentrations in patients with schizophrenia. Ann Clin Biochem 2008;45:44–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Zhu J, Lum PY, et al. Variations in DNA elucidate molecular networks that cause disease. Nature 2008;452:429–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y, Dolle ME, Imholz S, et al. Multiple genetic variants along candidate pathways influence plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. J Lipid Res 2008;49:2582–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins M, Province M, Heiss G, et al. NHLBI Family Heart Study: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:1219–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junyent M, Arnett D, Tsai M, et al. Genetic variants at the PDZ-interacting domain of the scavenger receptor class B type I interact with dietary habits to influence the risk of metabolic syndrome in obese participants from the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study. J Nutr 2009;139:842–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan D. SAS/AFR, metadata and the National Cancer Institutes Diet History Questionnaire: how to build a computer-assisted interview. Western Users of SAS Software, Eleventh Annual Conference, San Francisco. 2003. Available from: http://www.biostat.wustl.edu/derek/sasindex.html (cited December 2008)

- 20.Thompson FE, Subar AF, Brown CC, et al. Cognitive research enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire reports: results of an experimental validation study. J Am Diet Assoc 2002;102:212–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1089–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marinescu VD, Kohane IS, Riva A. MAPPER: a search engine for the computational identification of putative transcription factor binding sites in multiple genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 2005;6:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak KJ. Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5′ nuclease assay. Genet Anal 1999;14:143–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy C, Murray AM, Meaney S, Gafvels M. Regulation by SREBP-2 defines a potential link between isoprenoid and adenosylcobalamin metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;355:359–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinjan DA, Seawright A, Childs AJ, van Heuningen V. Conserved elements in Pax6 intron 7 involved in (auto)regulation and alternative transcription. Dev Biol 2004;265:462–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon AL, Liang L, Moffatt MF, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet 2007;39:1202–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolever TM, Mehling C. Long-term effect of varying the source or amount of dietary carbohydrate on postprandial plasma glucose, insulin, triacylglycerol, and free fatty acid concentrations in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:612–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopp W. The atherogenic potential of dietary carbohydrate. Prev Med 2006;42:336–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ordovas JM. Genetic influences on blood lipids and cardiovascular risk: tools for primary prevention. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89(suppl):1509S–17S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.