SYNOPSIS

Objectives.

We estimated the prevalence of self-reported diabetes in Hispanic subgroup (Puerto Rican, Mexican, Mexican American, Cuban, Dominican, Central and South American, and other Hispanic), non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic white populations aged 20 years and older.

Methods.

Using the National Health Interview Survey 1997–2005, we limited these analyses to 272,041 records of adults aged 20 years and older, including 46,749 records for Hispanic respondents. We used logistic regression to assess the strength of the association between race/ethnicity and self-reported diabetes before and after adjusting for selected characteristics.

Results.

Compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, Mexican American (odds ratio [OR] = 2.02; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.75, 2.34), Mexican (OR=1.52; 95% CI 1.31, 1.91), Puerto Rican (OR=1.53; 95% CI 1.23, 1.91), other Hispanic (OR=2.08; 95% CI 1.68, 2.58), and non-Hispanic black (OR=1.47; 95% CI 1.35, 1.61) respondents had greater odds of reporting diabetes. When compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, Mexican American respondents with less than a high school diploma had the lowest odds of reporting diabetes, while those with at least a college degree had greater odds of reporting diabetes. However, Puerto Rican respondents with less than a high school education, Mexican respondents with at least some college education, and other Hispanic respondents with at least a high school diploma/general equivalency diploma had greater odds of reporting diabetes.

Conclusions.

Although Hispanic respondents bear a greater burden of diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents, this burden is unevenly distributed across subgroups. These findings call attention to data disaggregation whenever possible for U.S. racial/ethnic populations classified under categories considered homogeneous.

Diabetes mellitus is a major public health problem in the United States.1 Recent data on prevalence of diabetes suggest that non-Hispanic black (14.5%) and Mexican American (15.0%) adults exhibited higher age-adjusted prevalence than non-Hispanic white adults (8.8%).2 By presenting information for Mexican American adults only, these national estimates fail to distinguish the heterogeneity in diabetes prevalence across subgroups within the Hispanic population. For example, data from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES, 1982–1984) show that the prevalence of diabetes was higher for Mexican American (23.9%) and Puerto Rican (26.1%) respondents than for Cuban respondents (15.8%).3

Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System show variations in the age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes among Hispanic people for selected states populated with different Hispanic subgroups, i.e., California (10.9%), Texas (10.5%), Puerto Rico (10.0%), New York/New Jersey (8.0%), and Florida (7.2%).4 Although this report did not present estimates specific to Hispanic subgroups residing in those states, U.S. Census data suggest that Mexican American people are more likely to reside in California and Texas, Puerto Rican people in New York and New Jersey, and Cuban people in Florida.5 Given the continuous growth and diversity of the Hispanic population, studies presenting information on Hispanic subgroups are imperative to expand our understanding of the Hispanic population's health.

The availability of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the only national data available on several racial/ethnic groups and subgroups, affords the opportunity to ascertain the prevalence of self-reported diabetes in Hispanic subgroups (e.g., Puerto Rican, Mexican, Mexican American, Cuban, Dominican, Central and South American, and other Hispanic) and non-Hispanic (black and white) adults aged 20 years or older before and after adjusting for selected characteristics for the years 1997–2005.

METHODS

NHIS is a national survey that uses a three-stage stratified cluster probability sampling design to conduct annual face-to-face household interviews of the U.S. noninstitutionalized civilian population. A complete description of the survey, plan, and design has been provided elsewhere.6,7 NHIS contains a core set of questions (repeated yearly) and supplemental questions/modules. For this study, we extracted data from the Public-Use Person and Sample Adult files for the years 1997–2005 for records of adults aged 18 years and older, yielding a sample of 289,707. The Person file includes a wide range of information asked to an adult in the household on behalf of all members of the household, while the Adult file includes more specific information (e.g., health and health-related information) obtained from a randomly chosen adult aged 18 years or older in the household. The response rates ranged from 86.1% (1999 and 2005) to 90.3% (1997) for the Person sample and 69.0% (2005) to 80.4% (1997) for the Adult sample.

The outcome, self-reported diabetes (hereafter referred to as “diabetes”), was collected using the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” For women, the phrase “other than during pregnancy” was added prior to this question to exclude cases of gestational diabetes. The main independent variable was race/ethnicity. We established ethnicity using the question, “Do any of these groups represent (Person)'s national origin or ancestry?” with Hispanic as a yes/no choice for the years 1997 and 1998 and, “Do you consider yourself Hispanic/Latino?” with choices of yes/no for the years 1999–2005. In addition, for participants who answered “yes” to the ethnicity question, a follow-up question was asked to query about the group that represents the participants' country of origin or ancestry. The following choices were offered: multiple Hispanic, Puerto Rican, Mexican-Mexicano, Mexican American (including Chicano), Cuban/Cuban American, other Latin American, other Spanish, other—specify (recoded by NHIS as Hispanic/Spanish non-specific type, Hispanic/Spanish type refused, Hispanic/Spanish type not ascertained, Hispanic/Spanish type don't know), and not Hispanic/Spanish origin. Starting in 1999, the following choices were added: Dominican (Republic) and Central and South American.

We determined race using the question, “What race do you consider yourself to be?” The choices were further categorized as white, black/African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, other, and multiple races. For these analyses, we defined race/ethnicity as Puerto Rican, Mexican, Mexican American, Cuban, Dominican, Central and South American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic white. We kept Mexican and Mexican American respondents as separate groups in the analyses because their identification as two distinct groups may represent issues associated with acculturation/assimilation to U.S. society through ethnic identity, country of birth, and Mexican culture ownership or attachment, regardless of whether they were born in the U.S. or Mexico. The analytical sample size comprised 272,041 records of adults aged 20 years and older, including 46,749 records for Hispanic respondents.

We included variables considered to be risk factors or potential confounders for diabetes8 in these analyses. We included gender (male/female) and U.S. region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) in the analysis as collected by NHIS. We included age in the analysis as continuous and categorical (20–44 years, 45–64 years, and 65–85 years, as 85 years was adjudicated to those aged 85 years or older). We specified marital status as married, divorced, widowed, or single. We categorized nativity status or country of birth as U.S.-born (individuals born in the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia) and island/foreign-born (individuals born in Puerto Rico, Guam, and other outlying territories of the U.S., as well as people not born in the U.S.). The island/foreign-born respondents were asked how long they had been in the U.S., with categories ranging from less than one year to 15 years or more. For analytical purposes, we created a variable combining nativity status and length of stay in the U.S. and coded it as island/foreign-born with less than five years in the U.S., island/foreign-born with five to nine years in the U.S., island/foreign-born with 10 or more years in the U.S., and U.S.-born. To adjust for any potential differences in diabetes prevalence during the nine years of the aggregated data, we created a variable for survey year and included it in the analysis.

Health insurance data were collected using a detailed question regarding multiple sources of insurance and coded as private, public, and noncoverage. Education was collected as a continuous variable, and based on its distribution in the study population, was categorized as less than high school, high school graduate or general equivalency diploma (GED), some college, and college graduate and higher. Income was collected by asking each participant to select his/her total annual income from 12 categories (ranging from $0 to $75,000 and higher, as well as a refusal category) and was adjusted to the year 1997 income using the inflation calculator developed by the Consumer Price Index.9 Specifically, the incomes in NHIS 1997–2005 were adjusted to the equivalent dollar amount in NHIS 1997, with income categorized as <$20,000, $20,000 to $34,999, $35,000 to $54,999, and ≥$55,000. Due to the large number of missing values for this variable, we used NHIS multiple imputation income files for these analyses.10 Using the U.S. Census,11 occupation was recoded into six categories: (1) executive, managerial, and professional; (2) technical, sales, and administrative support; (3) services; (4) farming, forestry, and fishing; (5) precision production, craft, and repair; and (6) operators, fabricators, and laborers.

Body mass index (BMI) in kilograms/meter squared (kg/m2), calculated using self-reported weight and height by NHIS, was included in the analysis as continuous and categorical (<25.0 kg/m2 for underweight and healthy weight and >25.0 kg/m2 for overweight, including obese).12,13 Leisure-time physical activity, defined as vigorous activities for at least 10 minutes that cause heavy sweating or large increases in breathing or heart rate, was categorized as: no more than five times a week, six or more times a week, never, and unable to do physical activity. Smoking status (current, former, or never) and alcohol consumption in the past year (current, former, or lifetime abstainer) were included in the analysis as collected by NHIS.

Statistical analysis

We calculated prevalence of diabetes for selected characteristics by race/ethnicity. We determined significant differences by using Chi-square statistics for multiple comparisons. We used logistic regression to assess the strength of the association between race/ethnicity and self-reported diabetes before and after adjusting for selected characteristics. Specifically, we were interested in examining the contribution of demographic characteristics, health-related factors, as well as socioeconomic indicators and access to care to the association of interest. Thus, the following models were specified: (1) crude odds ratios (crude ORs); (2) ORs adjusted for age, gender, marital status, survey year, U.S. region of residence, and nativity status/length of stay in the U.S. (Model 1); (3) ORs additionally adjusted for BMI (continuous), physical activity, and smoking (Model 2); and (4) ORs additionally adjusted for health insurance, education, income, and occupation (Model 3).

To determine whether the strength of the association observed between race/ethnicity and self-reported diabetes differed according to gender, education, and income, we tested interaction terms in a separate, fully adjusted model. In addition, because nativity status has been found to be associated with diabetes,14,15 we tested an interaction term between race/ethnicity and nativity status. The number of records available for the multivariable logistic regression varied according to the covariates included in the model.

We carried out all data management procedures using SAS® software.16 We conducted statistical analyses using SUDAAN17 because of its ability to take into account the complex sampling design in calculating unbiased standard error (SE) estimates. In addition, to account for the population size across the NHISs included in the analyses, we first combined data from the nine survey years and then created a new weight variable to calculate the mean of the population size across the nine years.6 Sample sizes presented in Table 1 were unweighted, but all other estimates (proportions, SEs, and ORs with their 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were weighted.

Table 1.

Prevalence of diabetesa for selected characteristics among Hispanic subgroup, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic white populations: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2005

aUnadjusted prevalence and standard errors

bAll p-values for stratum-adjusted Chi-square tests were <0.01 with the exception of gender. All p-values for stratum-specific Chi-square statistics within Hispanic subgroups and non-Hispanic groups were <0.05 with the exception of gender for Puerto Rican (p=0.11), Mexican American (p=0.57), Cuban (p=0.81), Dominican (p=0.42), Central and South American (p=0.53), and other Hispanic (p=0.97) respondents; marital status for Dominican respondents (p=0.06); region for the Puerto Rican (p=0.24) and Cuban (p=0.66) groups; nativity status for Dominican (p=0.06) and Central and South American (p=0.33) people; and income for Puerto Rican (p=0.72), Mexican (p=0.71), Mexican American (p=0.87), Cuban (p=0.78), Central and South American (p=0.62), other Hispanic (p=0.76), and non-Hispanic black (p=0.60) respondents.

GED = general equivalency diploma

RESULTS

The overall unadjusted prevalence of diabetes was 7.4% (SE=0.07, data not shown), with Puerto Rican (11.0%), Mexican American (10.2%) and non-Hispanic black (10.2%) respondents exhibiting the highest prevalence, and Mexican (6.2%), Dominican (5.2%), and Central and South American (4.0%) respondents reporting the lowest prevalence (Table 1). Regardless of their race/ethnicity, NHIS survey respondents who were older, widowed, had less than a high school education, had public insurance, were overweight/obese, were former smokers and drinkers, and were physically inactive had a higher prevalence of self-reported diabetes. Men reported a higher prevalence of diabetes than women with the exception of Mexican, Dominican, and non-Hispanic black men. U.S.-born individuals, regardless of their race/ethnicity, reported a higher prevalence of diabetes than island/foreign-born respondents. However, this was not true for Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican respondents: island-born individuals reported a higher prevalence of diabetes than those born in the U.S.

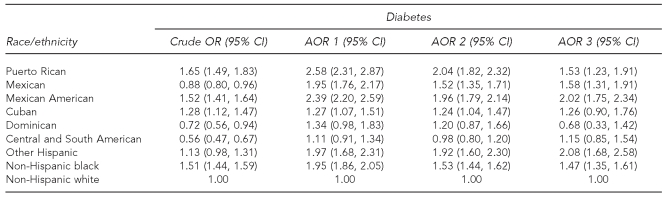

In the unadjusted analysis, compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, Puerto Rican (OR=1.65; 95% CI 1.49, 1.83), Mexican American (OR=1.52; 95% CI 1.41, 1.64), and non-Hispanic black (OR=1.51; 95% CI 1.44, 1.59) respondents had greater odds of reporting diabetes (Table 2). In contrast, the odds of diabetes were lower for Mexican (OR=0.88; 95% CI 0.80, 0.96), Dominican (OR=0.72; 95% CI 0.56, 0.94), and Central and South American (OR=0.56; 95% CI 0.47, 0.67) respondents. After adjusting for selected covariates including income and education, these associations remained significant for Puerto Rican (OR=1.53; 95% CI 1.23, 1.91), Mexican American (OR=2.02; 95% CI 1.75, 2.34), and non-Hispanic black (OR=1.47; 95% CI 1.35, 1.61) respondents. Moreover, the association was reversed for Mexican respondents (OR=1.58; 95% CI 1.31, 1.91) and emerged for other Hispanic respondents (OR=2.08; 95% CI 1.68, 2.58).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios (95% CI)a for diabetes among Hispanic subgroup and non-Hispanic adults: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2005

aCrude association between race/ethnicity and self-reported diabetes (crude OR); ORs adjusted for age, gender, marital status, survey year, U.S. region, and nativity status/length in the U.S. (AOR 1); additionally adjusted for body mass index (continuous), physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking (AOR 2); and additionally adjusted for health insurance, education, income, and occupation (AOR 3).

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

The association between race/ethnicity and diabetes differed with education (p<0.02; Table 3). When compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, the odds of reporting diabetes was greater in Mexican American and non-Hispanic respondents regardless of education. However, among Mexican American respondents, those with less than a high school diploma had the lowest odds of diabetes (OR=1.58), while those with at least a college degree had the greater odds of having diabetes (OR=2.69). Compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, the odds of diabetes was greater for Puerto Rican respondents with less than a high school education, Mexican respondents with at least some college education, and other Hispanic respondents with at least a high school diploma/GED. We observed no interaction effects between race/ethnicity and each of the following variables: gender, income, and nativity status.

Table 3.

Adjusted oddsa for diabetes among Hispanic subgroup and non-Hispanic adults according to educational attainment: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2005

aORs adjusted for age, gender, marital status, survey year, U.S. region, nativity status/length in the U.S., body mass index (continuous), physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, health insurance, income, and occupation.

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

GED = general equivalency diploma

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to report national estimates for prevalence of diabetes for Hispanic subgroups other than Mexican American people since the HHANES (1982–1984).3 Our findings suggest that there is noticeable variation in diabetes not only across Hispanic subgroups, but also as compared with non-Hispanic white respondents. Although Puerto Rican, Mexican, Mexican American, and other Hispanic populations had greater odds of diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents, the strength of these associations differed by group, with the stronger ones observed for Mexican American and other Hispanic respondents. Moreover, these associations varied with education: Puerto Rican respondents with less than a high school diploma/GED, Mexican respondents with at least some college, and other Hispanic respondents with at least a high school diploma/GED exhibited greater odds of diabetes. However, when compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, the odds of diabetes was greater for Mexican American and non-Hispanic black respondents regardless of their education.

Data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994) and NHANES 1999–2002 suggest that Mexican American respondents have a higher prevalence of diabetes than non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black adults.18–20 However, the existing estimates on prevalence of diabetes are only relevant to Mexican American respondents, and they ignore the growing diversity of the Hispanic population. Existing data on prevalence of diabetes from the HHANES (1982–1984) for Mexican American (23.9%), Puerto Rican (26.1%), and Cuban (15.8%) respondents do suggest variation across Hispanic subgroups.3 Thus, our results concur with HHANES estimates, indicating greater odds of having diabetes for Mexican American respondents represented by those self-identifying as Mexican American and Mexican compared with non-Hispanic white. Additionally, our analyses indicated that Puerto Rican respondents and those identified as other Hispanic also have greater odds of diabetes compared with non-Hispanic white respondents. Moreover, this variation could translate to differential mortality outcomes across Hispanic subgroups. In fact, a recent study observed variation for diabetes-related mortality, with Mexican American adults (251/100,000) exhibiting higher age-adjusted rates than Puerto Rican (204/100,000) and Cuban (101/100,000) adults.21

Important differences are also worth noting. First, when compared with non-Hispanic white respondents, the odds of diabetes were stronger for Mexican American respondents than for those identifying as Mexican in NHIS. Mexican respondents (85.7%) were more likely to be foreign-born than Mexican American respondents (16.5%, data not shown). Foreign-born status has been associated with lower levels of acculturation22 and, thus, less diabetes-related risk behaviors (e.g., diet, physical inactivity). For instance, it is possible that Mexican respondents may have been less likely to be exposed to a Western lifestyle, which has been associated with an increased risk for diabetes among Mexican American respondents. Second, the odds of diabetes for Puerto Rican respondents were similar to those observed for non-Hispanic black respondents. The latter may reflect the similarities of these two groups in terms of education, income, employment status, poverty, and segregation levels.23,24 These similarities also may be related to less favorable health profiles and may explain the differences in the greater odds of diabetes observed for these Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic black respondents relative to non-Hispanic white respondents.

Previous studies have found an inverse association between educational attainment and diabetes.25–28 Moreover, these studies have examined the role of gender,26 race/ethnicity25,28 or a combination of both27 on this association.28 However, the studies examining race/ethnicity have focused on non-Hispanic black and white27 populations or non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic populations as a whole.28 For instance, Borrell et al.28 found an inverse association between education and diabetes in non-Hispanic white and Hispanic adults only. The discrepancies between previous studies and our study's findings may be the result of the disaggregation of the Hispanic population.

Our study found associations between race/ethnicity and diabetes at all levels of education. For instance, for Mexican American and non-Hispanic black respondents, although associations were observed at all levels of education, the associations were stronger for those with higher educational attainment (college degree or higher). For Puerto Rican respondents, we observed an association among those with less than a high school education/GED, whereas for Cuban respondents we observed an association among those with some college. For Mexican and other Hispanic respondents, this association was observed among those with at least a high school education/GED. Consistent with previous studies, these findings underscore that the benefit of education on health may vary across racial/ethnic groups and subgroups.29–31 Importantly, for Hispanic respondents, these findings suggest that the health advantage paradox32,33 for mortality outcomes, observed mostly in Mexican American respondents despite low socioeconomic status, may not fit all outcomes and all Hispanic subgroups and perhaps should be reexamined.

We did not find an interaction between race/ethnicity and nativity status. This finding contrasts with previous studies suggesting a health advantage for foreign-born people14,15 and loss of this advantage with years in the U.S., probably due to acculturation to Western society.22,34 This difference in findings could be explained by the disaggregation of the Hispanic population into subgroups, as there are certain groups with higher proportions of island/foreign-born people (e.g., Mexican, Cuban, Dominican, and Central and South American groups) than others (e.g., Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and other Hispanic groups). However, this variation is not apparent when data are presented for Hispanic people as a whole. Thus, disaggregate data should be presented whenever possible, not only for Hispanic respondents, but also for other heterogeneous racial/ethnic groups, such as Asian people.

Strengths and limitations

Among the strengths of this study were the use of nine years of a national representative sample using the same sampling and data collection methodology; the range of data on health outcomes, risk behaviors, and lifestyles available in NHIS; the large sample size, which allowed us to control for numerous potential confounders and examine interactions; and the availability of data collecting information on Hispanic subgroups in the U.S.

Important limitations included the cross-sectional nature of the data that precluded us from making inferences regarding cause and effect, as well as the self-reported nature of the data collection. However, self-reported data for diabetes are highly correlated with physicians' records.35,36 Moreover, the unadjusted prevalence reported in this study (7.4%) was higher than the recent unadjusted prevalence of diagnosed diabetes reported for NHANES 1999–2004 (7.0%).19 Thus, any underestimation that may have occurred in our study would have been negligible. Because Hispanic respondents, regardless of their subgroups, are less likely to have health insurance, misclassification in reporting diabetes may have occurred and it is likely to be differential and underestimate our results. Finally, individuals who agreed to participate in NHIS, regardless of their race/ethnicity, may be different from those who refused or chose not to participate. However, without knowing the race/ethnicity or diabetes status of those refusing to participate in the survey, this refusal may either result in nondifferential or differential bias leading the results toward or away from the null.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that Hispanic respondents bear a greater burden of diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents. However, this burden is not evenly distributed across Hispanic subgroups, with Mexican American and other Hispanic populations carrying the heavier load. Puerto Rican and Mexican respondents, although exhibiting greater odds of diabetes than non-Hispanic white respondents, had odds similar to non-Hispanic black people. These findings call attention to data disaggregation whenever possible to reduce and eventually eliminate health disparities in populations classified under categories considered as homogenous in the U.S.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant (R03DE017901 to Luisa Borrell), the Columbia University Diversity Initiative Award (to Luisa Borrell), and the Columbia Center for the Health of Urban Minorities (Natalie Crawford).

REFERENCES

- 1.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:405–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2007, with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Ezzati TM, Harris MI, Haynes SG, Juarez RZ, Knowler WC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in Mexican Americans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1982–1984. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:628–38. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.7.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics—selected areas, 1998–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(40):941–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman B. Census 2000 brief. Washington: Census Bureau (US); 2001. The Hispanic population. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. 2005 National Health Interview Survey: public use data release. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. [cited 2008 Sep 16]. Also available from: URL: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2005/srvydesc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Interview Survey: research for the 1995–2004 redesign. Vital Health Stat 2. 1999;(126) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association. Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;(27) Suppl 1:S11–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (US) Consumer price indexes, CPI inflation calculator. [cited 2007 Jul 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.bls.gov/bls/inflation.htm.

- 10.Schenker N, Raghunathan TE, Chiu P-L, Makue DM, Zhang G, Cohen AJ. Multiple imputation of family income and personal earnings in the National Health Interview Survey: methods and examples. 2006. [cited 2008 Jul 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/tecdoc.pdf.

- 11.Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (US) Standard occupational classification. [cited 2007 Jul 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.bls.gov/soc/soc_majo.htm.

- 12.NHLBI Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. J Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):S51–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Consultation on Obesity. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894(i-xii):1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dey AN, Lucas JW. Adv Data. 2006. Physical and mental health characteristics of U.S.- and foreign-born adults: United States, 1998–2003; pp. 1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh GK, Hiatt RA. Trends and disparities in socioeconomic and behavioural characteristics, life expectancy, and cause-specific mortality of native-born and foreign-born populations in the United States, 1979–2003. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:903–19. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SAS Institute Inc. SAS®/STAT: Version 9.1. Cary (NC): SAS Institute Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN: Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, Eberhardt MS, Goldstein DE, Little RR, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:518–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong KL, Cheung BM, Wong LY, Wat NM, Tan KC, Lam KS. Prevalence, treatment, and control of diagnosed diabetes in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Eberhardt MS, Flegal KM, Engelgau MM, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1263–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith CAS, Barnett E. Diabetes-related mortality among Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans in the United States. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;18:381–7. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005001000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mainous AG, III, Majeed A, Koopman RJ, Baker R, Everett CJ, Tilley BC, et al. Acculturation and diabetes among Hispanics: evidence from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:60–6. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrell LN. Racial identity among Hispanics: implications for health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:379–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amaro H, Zambrana RE. Criollo, mestizo, mulato, LatiNegro, indigena, white, or black? The US Hispanic/Latino population and multiple responses in the 2000 Census. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1724–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.11.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brancati FL, Whelton PK, Kuller LH, Klag MJ. Diabetes mellitus, race, and socioeconomic status. A population-based study. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:67–73. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang M, Chen Y, Krewski D. Gender-related differences in the association between socioeconomic status and self-reported diabetes. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:381–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robbins JM, Vaccarino V, Zhang H, Kasl SV. Socioeconomic status and type 2 diabetes in African American and non-Hispanic white women and men: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:76–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borrell LN, Dallo FJ, White K. Education and diabetes in a racially and ethnically diverse population. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1637–42. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams DR. Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: measurement and methodological issues. Int J Health Serv. 1996;26:483–505. doi: 10.2190/U9QT-7B7Y-HQ15-JT14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:173–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep. 1986;101:253–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hazuda HP, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Eifler CW. Effects of acculturation and socioeconomic status on obesity and diabetes in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:1289–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kehoe R, Wu SY, Leske MC, Chylack LT., Jr. Comparing self-reported and physician-reported medical history. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:813–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngo DL, Marshall LM, Howard RN, Woodward JA, Southwick K, Hedberg K. Agreement between self-reported information and medical claims data on diagnosed diabetes in Oregon's Medicaid population. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:542–4. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]