Abstract

Objective To compare the risk of acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with rosiglitazone and pioglitazone.

Design Retrospective cohort study.

Setting Ontario, Canada.

Participants Outpatients aged 66 years and older who were started on rosiglitazone or pioglitazone between 1 April 2002 and 31 March 2008.

Main outcome measure Composite of death or hospital admission for either acute myocardial infarction or heart failure. In a secondary analysis, each outcome was also examined individually.

Results 39 736 patients who started on either pioglitazone or rosiglitazone were identified. During the six year study period, the composite outcome was reached in 895 (5.3%) of patients taking pioglitazone and 1563 (6.9%) of patients taking rosiglitazone. After extensive adjustment for demographic and clinical factors and drug doses, pioglitazone treated patients had a lower risk of developing the primary outcome than did patients treated with rosiglitazone (adjusted hazard ratio 0.83, 95% confidence interval 0.76 to 0.90). Secondary analyses revealed a lower risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio 0.86, 0.75 to 0.98) and heart failure (0.77, 0.69 to 0.87) with pioglitazone but no significant difference in the risk of acute myocardial infarction (0.95, 0.81 to 1.11). One additional composite outcome would be predicted to occur annually for every 93 patients treated with rosiglitazone rather than pioglitazone.

Conclusions Among older patients with diabetes, pioglitazone is associated with a significantly lower risk of heart failure and death than is rosiglitazone. Given that rosiglitazone lacks a distinct clinical advantage over pioglitazone, continued use of rosiglitazone may not be justified.

Introduction

Diabetes affects approximately 200 million people worldwide, including more than a quarter of those aged 65 and above in developed countries.1 Although diet and exercise are first line treatments, many patients need treatment with oral hypoglycaemic drugs or insulin with the goal of improving glycaemic control and preventing microvascular and macrovascular complications. Drugs that act as insulin sensitisers have particular appeal because most patients with type 2 diabetes show some degree of insulin resistance.2

The thiazolidinediones rosiglitazone and pioglitazone are insulin sensitising agents that improve glycaemic control and a variety of other surrogate outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, weight gain, fluid retention, and heart failure have been reported with both drugs.3 4 The mechanism is incompletely understood, but these effects seem to result at least in part from stimulation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs), the primary physiological mechanism by which these drugs improve glycaemic control. In the nephron, activation of PPARγ promotes expression of epithelial sodium channels, increasing the absorption of salt and water.5 6 Rosiglitazone and pioglitazone have both been associated with heart failure in case reports, observational studies, and randomised trials. Consequently, the overall cardiovascular safety of these drugs has been questioned.3 7 8

In addition to concerns about heart failure, a recent meta-analysis of 42 randomised trials comparing rosiglitazone with placebo or active treatment found an increased risk of acute myocardial infarction and a trend towards increased mortality with the drug.9 However, many of the trials included in the study were unpublished, the number of outcomes was relatively low, and a Bayesian analysis of the original data found no significant increase in the risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death during treatment with rosiglitazone.10 A subsequent meta-analysis concluded that, compared with either placebo or treatment with other oral hypoglycaemic agents, use of rosiglitazone was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and heart failure but not cardiovascular mortality.11

Concerns about the safety of rosiglitazone prompted an unplanned interim analysis of the Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiac Outcomes and Regulation of Glycaemia in Diabetes (RECORD) trial, which showed an increased risk of heart failure with the drug but no increase in the death from cardiac causes or all cause mortality.12 However, the design, results, and interpretation of this trial have been heavily criticised.13

The cardiovascular risks of rosiglitazone thus remain incompletely characterised, and whether the adverse effects of thiazolidinediones are a “class effect” is also unclear. Both drugs seem to be capable of precipitating heart failure, but limited evidence indicates that pioglitazone may be associated with a lower risk of cardiac events. It has more favourable effects on serum lipids than does rosiglitazone,14 15 and a large randomised trial of patients with existing macrovascular disease suggested that treatment with pioglitazone prevents cardiovascular events.16 A subsequent meta-analysis reached similar conclusions, in contrast to the meta-analyses involving rosiglitazone,17 and another meta-analysis indicated that pioglitazone might carry a lower risk of heart failure than does rosiglitazone but with no difference in death from cardiovascular causes.18 Several observational studies have provided conflicting conclusions about the cardiovascular safety of the thiazolidinediones, and the Food and Drug Administration has issued boxed warnings for both drugs.18 19 20 21 22 23

Given the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes, as well as the uncertainty as to whether rosiglitazone and pioglitazone carry differential cardiovascular risks and the impracticability of a head to head trial of the two drugs, we explored the relative cardiovascular safety of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone in a population of approximately 1.6 million older outpatients.

Methods

Setting

We did a population based retrospective cohort study of Ontario residents aged 66 years or above who started treatment with either rosiglitazone or pioglitazone between 1 April 2002 and 31 March 2008. These people have universal access to hospital care, physicians’ services, and prescription drug coverage.

Data sources

We examined the computerised prescription records of the Ontario Public Drug Benefit Program, which contains comprehensive records of prescription drugs dispensed to Ontario residents 65 years of age or older. We did not study patients during their first year of eligibility for prescription drug coverage (age 65) to avoid incomplete drug records. We identified hospital visits from the national ambulatory care reporting system database and the Canadian Institute for Health information discharge abstract database, which contain detailed diagnostic and procedural information on hospital admissions. We used the Ontario health insurance plan database to identify claims for inpatient and outpatient physician services and the Ontario diabetes database to determine the duration of diabetes in each patient.24 Basic demographic information, including date of death, came from the registered persons database, which contains a unique entry for all Ontario residents ever issued a health card. These databases are routinely linked for the purposes of studying drug safety,25 26 27 and we linked them in an anonymous fashion by using encrypted 10 digit health card numbers.

Design and analysis

We defined the index date as the date when either rosiglitazone or pioglitazone was first prescribed. To include only patients naive to thiazolidinediones, we excluded people who had received a prescription for either of these drugs in the year before the index date. We also excluded patients who had received a prescription for insulin during the same interval, because the addition of a thiazolidinedione to insulin treatment is generally contraindicated and because we anticipated that patients started on a thiazolidinedione while on insulin were likely to be systematically different from patients not receiving insulin. We included patients who switched between low and high doses of the same drug, but we censored those who switched from one thiazolidinedione to the other, as well as those who stopped receiving prescriptions for rosiglitazone or pioglitazone, defined by the date of their final prescription plus 1.5 times the prescription days’ supply to avoid excluding patients who died or were admitted to hospital during treatment. Finally, we censored after three years of total observation or at the end of the study period (31 March 2008), whichever occurred first.

The primary outcome was a composite of death from any cause or admission to hospital or visit to an emergency department for either acute myocardial infarction or heart failure. Secondary analyses explored each of these outcomes individually. We identified the date of death by using the registered persons database and hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction and heart failure by using ICD-10 (international classification of disease and related health problems, 10th revision) codes I20, I21, I22 (for acute myocardial infarctions), and I50 (for heart failure). The date of death or admission served as the outcome date in all analyses. We considered only the first admission for a study outcome in patients who had multiple admissions during the study period.

We compared patients’ baseline characteristics between treatment groups by using standardised differences—the difference in means divided by a pooled estimate of the standard deviation of the variable. In contrast to significance testing, standardised differences are not influenced by sample size; values lower than 0.10 suggest negligible differences in the mean value of the characteristic between groups.28 We did time to event analyses for the primary outcome with rosiglitazone as reference because its risks, although incompletely understood, are better characterised than those of pioglitazone. The analysis incorporated a dose-response assessment by considering low dose pioglitazone (15 mg), high dose pioglitazone (30 mg and 45 mg), low dose rosiglitazone (2 mg and 4 mg), and high dose rosiglitazone (8 mg) as time dependent covariates in the regression model, with high dose rosiglitazone as the reference group.

We constructed Kaplan-Meier curves to characterise survival over time among patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone and made extensive adjustments for demographic and clinical variables (see web appendix) by using Cox proportional hazards regression. We verified the proportional hazards assumption by using visual inspection of the estimated log(−log) survival curves and by testing the statistical significance of a covariate that allowed treatment to have a time varying effect.

To estimate the absolute risk of cardiovascular harm for rosiglitazone relative to pioglitazone, we used the fitted Cox proportional hazards model to derive a marginal estimate of the number needed to treat to harm.29 From the fitted regression model, we calculated the predicted probabilities of the primary outcome and each secondary outcome at 365 days for each patient, assuming treatment with rosiglitazone. We then determined the mean of these probabilities across the sample; this is the marginal (or population average) probability of an event within 365 days, assuming that all patients received rosiglitazone. We repeated this exercise assuming that all patients received pioglitazone. We then calculated the difference between the two marginal probabilities, assuming that all patients were exposed to rosiglitazone and then that all were exposed to pioglitazone. This is the marginal risk difference between rosiglitazone and pioglitazone at 365 days, and the inverse of this represents the number needed to treat to harm. If no patients in the sample experienced the event of interest on day 365, we used linear interpolation to estimate the risk of the event on that date by using the two event times closest to 365, with one event time preceding and one event time following day 365.

Results

During the 72 month study period, we identified 39 736 patients who started treatment with a thiazolidinedione, of whom 22 785 (57.3%) started rosiglitazone treatment and 16 951 (42.7%) started on pioglitazone. We followed patients on rosiglitazone for a median of 292 (interquartile range 124-448) days and those on pioglitazone for a median of 294 (87-487) days. Collectively, we followed patients for a total of 38 752 person years of treatment. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients. Overall, patients starting treatment with rosiglitazone and pioglitazone were highly similar in terms of demographics, medical illnesses, comorbidity measures, and concomitant drug use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Pioglitazone (n=16 951) | Rosiglitazone (n=22 785) | Standardised difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (interquartile range) age (years) | 72 (68-77) | 72 (68-77) | 0.01 |

| Age group (years): | |||

| 66-75 | 11 637 (68.7) | 15 744 (69.1) | 0.01 |

| 76-85 | 4 785 (28.2) | 6 349 (27.9) | 0.01 |

| ≥86 | 529 (3.1) | 692 (3.0) | 0.00 |

| Male sex | 8 839 (52.1) | 12 094 (53.1) | 0.02 |

| Duration of diabetes (years): | |||

| <2 | 1 179 (7.0) | 1 367 (6.0) | 0.04 |

| 2-5 | 1 921 (11.3) | 2 430 (10.7) | 0.02 |

| >5 | 13 851 (81.7) | 18 988 (83.3) | 0.04 |

| Cardiovascular admissions and procedures in previous 5 years: | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 591 (3.5) | 927 (4.1) | 0.03 |

| Congestive heart failure | 260 (1.5) | 401 (1.8) | 0.02 |

| Angina | 962 (5.7) | 1 426 (6.3) | 0.02 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 482 (2.8) | 697 (3.1) | 0.01 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 447 (2.6) | 684 (3.0) | 0.02 |

| Coronary angiography | 1 478 (8.7) | 2 168 (9.5) | 0.03 |

| Charlson score: | |||

| 0 | 4 704 (27.8) | 6 322 (27.7) | 0.00 |

| 1 | 2 909 (17.2) | 4 041 (17.7) | 0.02 |

| ≥2 | 3 472 (20.5) | 4 978 (21.8) | 0.03 |

| Not available | 5 866 (34.6) | 7 444 (32.7) | 0.04 |

| History of drug use in previous year: | |||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 10 252 (60.5) | 14 414 (63.3) | 0.06 |

| Angiotensin receptor antagonists | 5 248 (31.0) | 6 260 (27.5) | 0.08 |

| Aspirin | 2 993 (17.7) | 3 846 (16.9) | 0.02 |

| Other antiplatelet drugs | 793 (4.7) | 1 108 (4.9) | 0.01 |

| β adrenergic antagonists | 5 518 (32.6) | 7 665 (33.6) | 0.02 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 6 797 (40.1) | 8 842 (38.8) | 0.03 |

| Nitrates | 1 950 (11.5) | 2 769 (12.2) | 0.02 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 4 052 (23.9) | 5 595 (24.6) | 0.02 |

| Other diuretics | 3 156 (18.6) | 4 461 (19.6) | 0.02 |

| Spironolactone | 414 (2.4) | 566 (2.5) | 0.00 |

| Statins | 12 168 (71.8) | 16 300 (71.5) | 0.01 |

| Digoxin | 743 (4.4) | 1 030 (4.5) | 0.01 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 6 996 (41.3) | 9 178 (40.3) | 0.02 |

| Median (interquartile range) No of distinct drugs in previous year | 10 (7-13) | 10 (7-13) | 0.03 |

| Other oral hypoglycaemic agents in previous year: | |||

| Metformin | 13 677 (80.7) | 18 496 (81.2) | 0.01 |

| Sulphonylureas | 11 628 (68.6) | 15 710 (68.9) | 0.01 |

| Acarbose | 1 005 (5.9) | 1 152 (5.1) | 0.04 |

| Meglitinides | 159 (0.9) | 176 (0.8) | 0.02 |

| History of renal disease in previous 5 years | 575 (3.4) | 867 (3.8) | 0.02 |

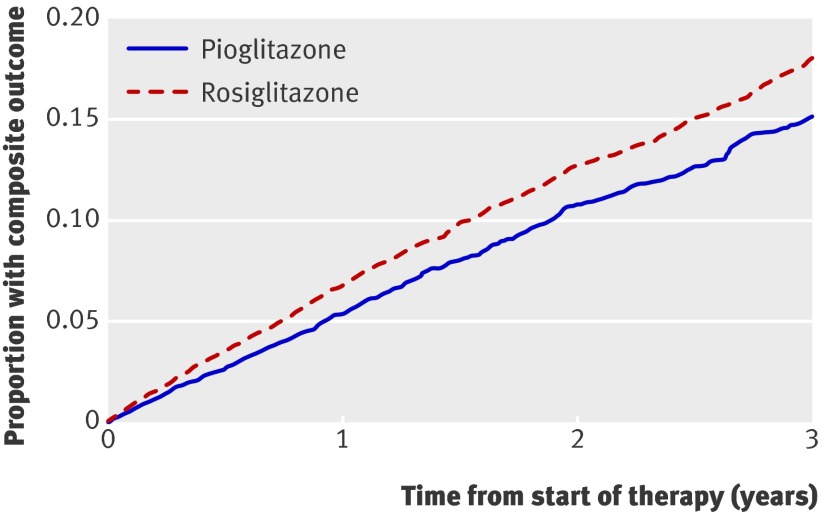

In total, 1563 (6.9%) patients receiving rosiglitazone and 895 (5.3%) receiving pioglitazone reached the primary composite outcome of death or admission to hospital for either acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure (fig 1). After extensive adjustment for potential confounding factors, we found that pioglitazone was associated with a significantly lower risk of the primary outcome compared with rosiglitazone (adjusted hazard ratio 0.83, 95% confidence interval 0.76 to 0.90). In terms of absolute risk, we estimate that approximately one additional composite outcome would be expected to occur annually for every 93 patients treated with rosiglitazone rather than pioglitazone.

Fig 1 Survival curves for primary outcome (composite of death or hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction or heart failure) from start of treatment with pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, adjusted for factors outlined in web appendix

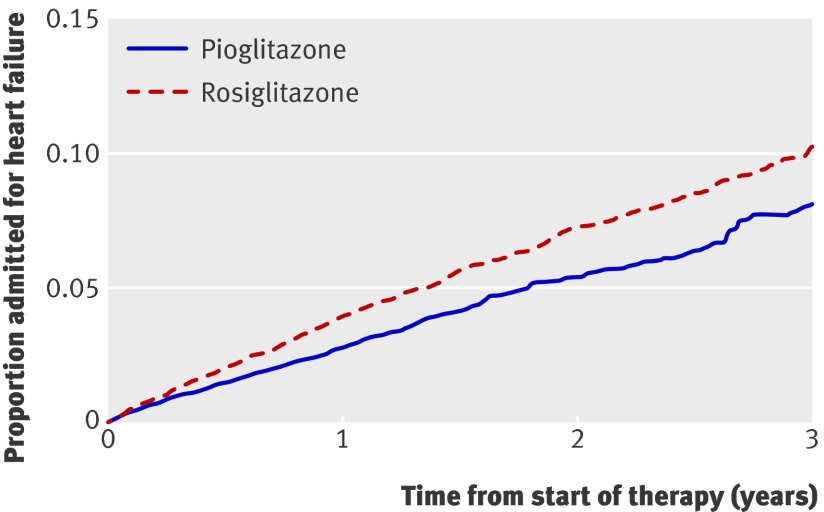

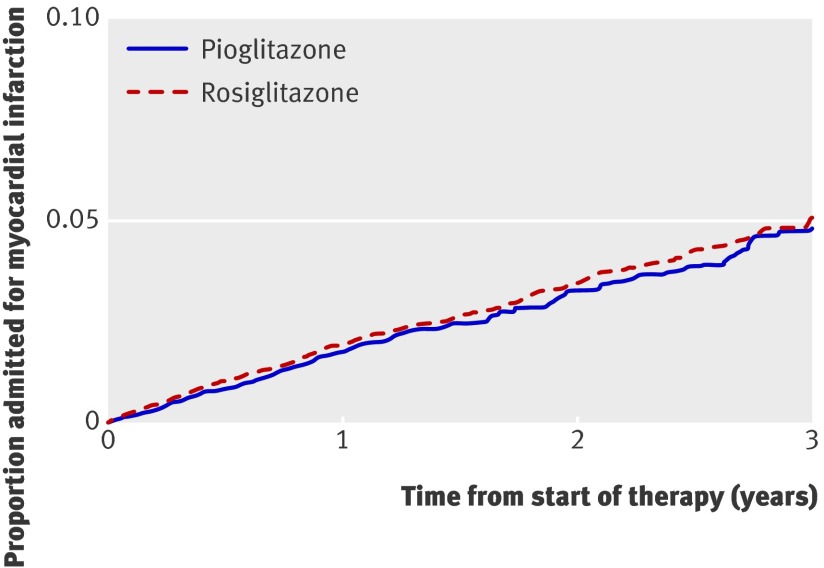

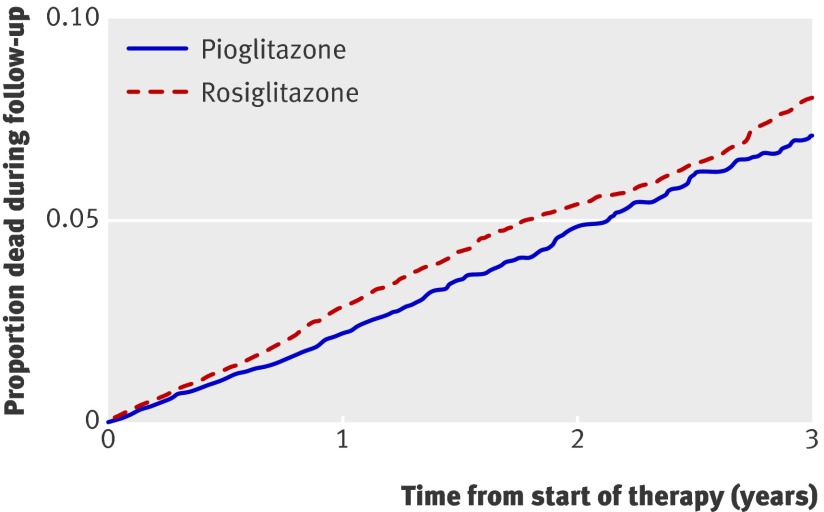

In the secondary analyses of each outcome individually, we studied 1330 admissions for heart failure, 698 admissions for acute myocardial infarction, and 1022 deaths (table 2). We found a lower risk of congestive heart failure during pioglitazone treatment compared with rosiglitazone treatment (adjusted hazard ratio 0.77, 0.69 to 0.87) (fig 2) but no significant difference in the risk of myocardial infarction (0.95, 0.81 to 1.11) (fig 3). Notably, patients treated with pioglitazone had a lower risk of death from all causes than did those treated with rosiglitazone (adjusted hazard ratio 0.86, 0.75 to 0.98) (fig 4). The estimated annual number needed to treat to harm for rosiglitazone compared with pioglitazone was 120 for congestive heart failure and 269 for death from any cause.

Table 2.

Risk of adverse cardiovascular events among patients treated with pioglitazone or rosiglitazone

| Events in pioglitazone patients (n=16 951) | Events in rosiglitazone patients (n=22 785) | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | 895 | 1563 | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.87) | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.90) |

| Secondary outcomes: | ||||

| Heart failure | 461 | 869 | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.84) | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.87) |

| Myocardial infarction | 273 | 425 | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.06) | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.11) |

| Death | 377 | 645 | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.94) | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98) |

*Cox proportional hazards model estimates adjusted for age; sex; duration of diabetes; residence in long term care facility; socioeconomic status (estimated from median residential income fifth); year of cohort entry; Charlson comorbidity index; number of distinct drugs in year before cohort entry; history in previous five years of renal disease or hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction, angina, congestive heart failure, coronary angiography, coronary artery bypass grafting, or percutaneous coronary intervention; and receipt in year preceding cohort entry of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists, β adrenergic antagonists, aspirin, other antiplatelet drugs, nitrates, calcium channel antagonists, thiazide diuretics, spironolactone, other diuretics, hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), digoxin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, metformin, sulphonylureas, acarbose, or meglitinides.

Fig 2 Survival curves for hospital admission for heart failure from start of treatment with pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, adjusted for factors outlined in web appendix

Fig 3 Survival curves for hospital admission for acute myocardial infarction from start of treatment with pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, adjusted for factors outlined in web appendix

Fig 4 Survival curves for death from any cause from start of treatment with pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, adjusted for factors outlined in web appendix

To test the robustness of our conclusions, we did several additional analyses. In the dose-response analysis, compared with high dose rosiglitazone, low dose rosiglitazone was not associated with a significantly lower risk of the composite outcome (adjusted hazard ratio 0.94, 0.83 to 1.07), whereas both high dose pioglitazone (0.76, 0.66 to 0.88) and low dose pioglitazone (0.83, 0.70 to 0.97) were. We replicated our analyses after excluding patients with heart failure or acute myocardial infarction who were assessed in the emergency department but not subsequently admitted to hospital. The findings were consistent with those obtained by using the full cohort. We also found similar results when we replicated our analyses without censoring after three years of treatment. Finally, because the meta-analysis of Nissen and Wolski received considerable media attention and influenced thiazolidinedione prescribing trends,30 we repeated our analyses but terminated follow-up one year earlier (31 March 2007) to reduce any potential contamination of our findings by changes in practice resulting from publication of the meta-analysis. These findings were again consistent with those derived by using the original study interval.

Discussion

Using the population based healthcare records of approximately 40 000 patients who started treatment with a thiazolidinedione over a six year period, we found considerable differences in the risk of heart failure and death between users of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone but no significant difference in the risk of myocardial infarction. Our findings suggest clinically important differences in the cardiovascular safety profiles of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone in clinical practice.

Interpretation of findings

Adverse effects of a class of drugs (class effects) are common in clinical medicine, and recent studies highlighting the cardiovascular risks of rosiglitazone have naturally raised questions about the safety of pioglitazone. Consequently, patients and clinicians have been faced with difficult decisions on the use of these drugs, which are often prescribed to patients with type 2 diabetes whose response to other oral agents is suboptimal but who are reluctant to start insulin. Our study provides direct evidence in otherwise comparable patients that pioglitazone is associated with a lower risk of adverse cardiovascular events and death than is rosiglitazone.

Why pioglitazone might be safer than rosiglitazone is not fully understood, but the possibility is supported by converging lines of evidence. Pioglitazone has more favourable effects on serum lipids than does rosiglitazone,14 15 and some evidence suggests that it also imparts anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects.31 Rosiglitazone is a far more potent agonist of PPARγ than is pioglitazone,32 and activation of PPARγ in the kidney seems to be an important mechanism of thiazolidinedione induced salt and water retention.5 These observations may explain the higher risk of heart failure with rosiglitazone, and we speculate that they also underlie the increased risk of death in patients taking the drug. Unlike rosiglitazone, pioglitazone has been found to significantly reduce ischaemic cardiovascular outcomes in a large randomised trial and a corresponding meta-analysis.16 17 Furthermore, although observational studies have reached differing conclusions about the relative safety of the thiazolidinediones, no studies have suggested a safety advantage for rosiglitazone.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study is the possibility that patients who were prescribed rosiglitazone were at a higher baseline risk of heart failure and death than those prescribed pioglitazone. However, several observations make this an unlikely explanation for our findings. The two groups of patients were highly similar (table 1), and any discrepancies are too minor to be likely to explain the large effect sizes seen in our study. Our findings are supported by biological plausibility,5 and the adjusted and unadjusted hazard ratios were similar. Finally, if the increased risks of heart failure and death with rosiglitazone simply reflected increased cardiac risk at baseline, one would expect to see a similar increase in the risk of acute myocardial infarction. This was not the case.

Other limitations of our work merit emphasis. Our findings derive from patients aged 66 years and older, and the generalisability of our findings to younger patients is not known. Miscoding is a potential threat to the validity of all observational studies, but previous validation studies estimate the positive predictive value of heart failure and myocardial infarction in our databases at approximately 90%.33 34 Moreover, differential miscoding between users of rosiglitazone and pioglitazone would be implausible in this setting.

Our study was designed to explore the comparative safety of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone. We cannot provide an assessment of the safety of pioglitazone relative to other hypoglycaemic agents, and our findings should not be interpreted as evidence that pioglitazone is devoid of cardiovascular toxicity. As with rosiglitazone, good evidence exists to show that the drug can cause heart failure.16 17 35 Unlike for rosiglitazone, however, no evidence exists to show that pioglitazone increases ischaemic events, and some evidence indicates that it may reduce cardiovascular morbidity in high risk patients with diabetes.16 17 Further research is needed to fully characterise the safety profile and net benefits of pioglitazone in clinical practice.

Conclusions and policy implications

In a large cohort of older patients starting treatment with a thiazolidinedione, we found that pioglitazone was associated with a lower risk of adverse cardiovascular events and death than was rosiglitazone. Given the accumulating evidence of harm with rosiglitazone treatment and the lack of a distinct clinical advantage for the drug over pioglitazone, questioning whether ongoing use of rosiglitazone is justified in any circumstance is reasonable. Pending the availability of additional data on the benefits and harms of these drugs and a clarification of their role in the pharmacotherapy of type 2 diabetes, we believe that clinicians should re-evaluate the appropriateness of new or ongoing treatment with rosiglitazone.

What is already known on this topic

Rosiglitazone and pioglitazone have been associated with congestive heart failure, and rosiglitazone has also been associated with acute myocardial infarction

Whether clinically important differences exist in the cardiac safety profiles of these drugs remains unclear

What this study adds

Rosiglitazone is associated with a clinically significant higher risk of heart failure and death than is pioglitazone but with no major difference in the risk of acute myocardial infarction

Given the absence of a distinct clinical advantage over pioglitazone, continued use of rosiglitazone is difficult to advocate

The long term safety of pioglitazone compared with other oral hypoglycaemic drugs remains uncertain

We thank Baiju Shah and Donald Redelmeier for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript and Ashif Kachra for assistance with preparing the manuscript.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. TG collected the data, and all authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation. DNJ drafted the article; all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication. DNJ is the guarantor.

Funding: This project was supported by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, which had no role in the design, analysis, writing, or interpretation of the study. DNJ is supported by a new investigator award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. PCA is supported by a career investigator award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. LLL is supported by a clinician scientist award from the Canadian Diabetes Association and Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The research ethics board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre approved the study.

The opinions, results, and conclusions are those of the authors, and no endorsement by Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-term Care or by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences is intended or should be inferred.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b2942

References

- 1.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haffner SM, D’Agostino R Jr, Mykkanen L, Tracy R, Howard B, Rewers M, et al. Insulin sensitivity in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Relationship to cardiovascular risk factors: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes Care 1999;22:562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stafylas PC, Sarafidis PA, Lasaridis AN. The controversial effects of thiazolidinediones on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Int J Cardiol 2009;131:298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kermani A, Garg A. Thiazolidinedione-associated congestive heart failure and pulmonary edema. Mayo Clin Proc 2003;78:1088-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan Y, Hao C, Cha DR, Rao R, Lu W, Kohan DE, et al. Thiazolidinediones expand body fluid volume through PPARgamma stimulation of ENaC-mediated renal salt absorption. Nat Med 2005;11:861-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Zhang A, Kohan DE, Nelson RD, Gonzalez FJ, Yang T. Collecting duct-specific deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma blocks thiazolidinedione-induced fluid retention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:9406-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zinn A, Felson S, Fisher E, Schwartzbard A. Reassessing the cardiovascular risks and benefits of thiazolidinediones. Clin Cardiol 2008;31:397-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solomon DH, Winkelmayer WC. Cardiovascular risk and the thiazolidinediones: deja vu all over again? JAMA 2007;298:1216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2457-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond GA, Kaul S. Rosiglitazone and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2007;357:938-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Loke YK, Furberg CD. Long-term risk of cardiovascular events with rosiglitazone: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2007;298:1189-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Jones NP, et al. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes—an interim analysis. N Engl J Med 2007;357:28-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Psaty BM, Furberg CD. The record on rosiglitazone and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2007;357:67-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle PJ, King AB, Olansky L, Marchetti A, Lau H, Magar R, et al. Effects of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone on blood lipid levels and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective review of randomly selected medical records. Clin Ther 2002;24:378-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg RB, Kendall DM, Deeg MA, Buse JB, Zagar AJ, Pinaire JA, et al. A comparison of lipid and glycemic effects of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1547-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the proactive study (prospective pioglitazone clinical trial in macrovascular events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:1279-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lincoff AM, Wolski K, Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE. Pioglitazone and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 2007;298:1180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lago RM, Singh PP, Nesto RW. Congestive heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes given thiazolidinediones: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2007;370:1129-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerrits CM, Bhattacharya M, Manthena S, Baran R, Perez A, Kupfer S. A comparison of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone for hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:1065-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipscombe LL, Gomes T, Levesque LE, Hux JE, Juurlink DN, Alter DA. Thiazolidinediones and cardiovascular outcomes in older patients with diabetes. JAMA 2007;298:2634-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margolis DJ, Hoffstad O, Strom BL. Association between serious ischemic cardiac outcomes and medications used to treat diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:753-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen CJ. The rosiglitazone story—lessons from an FDA Advisory Committee meeting. N Engl J Med 2007;357:844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karter AJ, Ahmed AT, Liu J, Moffet HH, Parker MM. Pioglitazone initiation and subsequent hospitalization for congestive heart failure. Diabet Med 2005;22:986-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care 2002;25:512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, Kopp A, Austin PC, Laupacis A, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the randomized aldactone evaluation study. N Engl J Med 2004;351:543-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mamdani M, Rochon P, Juurlink DN, Anderson GM, Kopp A, Naglie G, et al. Effect of selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors and naproxen on short-term risk of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park-Wyllie LY, Juurlink DN, Kopp A, Shah BR, Stukel TA, Stumpo C, et al. Outpatient gatifloxacin therapy and dysglycemia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1352-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, Normand SL, Streiner DL, Austin PC, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 2005;330:960-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin PC. Absolute risk reductions, relative risks, relative risk reductions, and numbers needed to treat can be obtained from a logistic regression model. J Clin Epidemiol 2009. Feb 18 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Shah BR, Juurlink DN, Austin PC, Mamdani MM. New use of rosiglitazone decreased following publication of a meta-analysis suggesting harm. Diabet Med 2008;25:871-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfutzner A, Marx N, Lubben G, Langenfeld M, Walcher D, Konrad T, et al. Improvement of cardiovascular risk markers by pioglitazone is independent from glycemic control: results from the pioneer study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1925-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young PW, Buckle DR, Cantello BC, Chapman H, Clapham JC, Coyle PJ, et al. Identification of high-affinity binding sites for the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone (BRL-49653) in rodent and human adipocytes using a radioiodinated ligand for peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998;284:751-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DS, Donovan L, Austin PC, Gong Y, Liu PP, Rouleau JL, et al. Comparison of coding of heart failure and comorbidities in administrative and clinical data for use in outcomes research. Med Care 2005;43:182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J 2002;144:290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jamieson A, Abousleiman Y. Thiazolidinedione-associated congestive heart failure and pulmonary edema. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:571-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]