Abstract

We used a large panel of pedigreed, genetically admixed house mice to study patterns of recombination rate variation in a leading mammalian model system. We found considerable inter-individual differences in genomic recombination rates and documented a significant heritable component to this variation. These findings point to clear variation in recombination rate among common laboratory strains, a result that carries important implications for genetic analysis in the house mouse.

THE rate of recombination—the amount of crossing over per unit DNA—is a key parameter governing the fidelity of meiosis. Recombination rates that are too high or too low frequently give rise to aneuploid gametes or prematurely arrest the meiotic cell cycle (Hassold and Hunt 2001). As a consequence, recombination rates should experience strong selective pressures to lie within the range defined by the demands of meiosis (Coop and Przeworski 2007). Nonetheless, classical genetic studies in Drosophila (Chinnici 1971; Kidwell 1972; Brooks and Marks 1986), crickets (Shaw 1972), flour beetles (Dewees 1975), and lima beans (Allard 1963) have shown that considerable inter-individual variation for recombination rate is present within populations. Recent studies examining the transmission of haplotypes in human pedigrees have corroborated these findings (Broman et al. 1998; Kong et al. 2002; Coop et al. 2008).

Here, we use a large panel of heterogeneous stock (HS) mice to study variation in genomic recombination rates in a genetic model system. These mice are genetically admixed, derived from an initial generation of pseudorandom mating among eight common inbred laboratory strains (DBA/2J, C3H/HeJ, AKR/J, A/J, BALB/cJ, CBA/J, C57BL/6J, and LP/J), followed by >50 generations of pseudorandom mating in subsequent hybrid cohorts (Mott et al. 2000; Demarest et al. 2001). The familial relationships among animals in recent generations were tracked to organize the mice into pedigrees. In total, this HS panel includes ∼2300 animals comprising 85 families, 8 of which span multiple generations. The remainder consists of nuclear families (sibships) that range from 1 to 34 sibs, with an average of 9.6 sibs (Valdar et al. 2006) (Table 1). Additional details on the derivation and history of these HS mice are provided elsewhere (see Mott et al. 2000; Demarest et al. 2001; Shifman et al. 2006).

TABLE 1.

Heterogeneous stock mouse pedigrees

| Pedigree | Pedigree class | No. of nonoverlapping sibships in the pedigree | No. of retained sibships | No. of meioses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Multigenerational | 17 | 17 | 464 |

| 2 | Multigenerational | 27 | 20 | 728 |

| 3 | Multigenerational | 23 | 19 | 602 |

| 4 | Multigenerational | 14 | 9 | 254 |

| 5 | Multigenerational | 11 | 9 | 242 |

| 6 | Multigenerational | 5 | 3 | 68 |

| 7 | Multigenerational | 4 | 3 | 100 |

| 8 | Multigenerational | 2 | 1 | 16 |

| 9 | Sibshipa | 2 | 1 | 20 |

| 32–85 | Sibship | 51 | 1146 | |

| Total | 180 | 132 | 3640 |

This family was composed of two sibships sharing a common mother but with different fathers.

With the exception of several founding individuals, most of these HS mice have been genotyped at 13,367 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome (available at http://gscan.well.ox.ac.uk/). Although the publicly available HS genotypes have passed data quality filters (Shifman et al. 2006), we took several additional measures to ensure the highest possible accuracy of base calls. First, data were cleansed of all non-Mendelian inheritances, and genotypes with quality scores <0.4 were removed. Genotypes that resulted in tight (<10 cM in sex-specific distance) double recombinants were also omitted because strong positive crossover interference in the mouse renders such closely spaced crossovers biologically very unlikely (Broman et al. 2002). A total of 10,195 SNPs (including 298 on the X chromosome) passed these additional quality control criteria; the results presented below consider only this subset of highly accurate (>99.98%) and complete (<0.01% missing) genotypes. The cleaned data are publicly available (at http://cgd.jax.org/mousemapconverter/).

We used the chrompic program within CRI-MAP (Lander and Green 1987; Green et al. 1990) to estimate the number of recombination events in parental meioses. The algorithm implemented in chrompic first phases parent and offspring genotypes using a maximum-likelihood approach. Next, recombination events occurring in the parental germline are identified by comparing parent and offspring haplotypes across the genome (Green et al. 1990). For example, a haplotype that first copies from one maternal chromosome and then switches to copying from the other maternal chromosome signals a recombination event in the maternal germline.

chrompic is very memory intensive and cannot handle the multigenerational pedigrees and the large sibships included in the HS panel. To circumvent these computational limitations, several modifications to the data were implemented. First, the eight multigenerational pedigrees were split into 102 nonoverlapping sibships, retaining grandparental information when available (Table 1). Two of these sibships shared a common father, but had different mothers. Combined with the 77 single-generation families in the HS panel, this data set then comprised a total of 180 sibships (one single-generation family consisted of two sibships with a common mother but different fathers). Second, we eliminated 35 of the 180 sibships for which neither parent was genotyped, and 13 additional families that featured only one genotyped parent and fewer than seven offspring (Table 1). These filters were implemented to avoid overestimating crossover counts (Cox et al. 2009). Finally, large sibships were subdivided: sibships with >13 progeny were split into two groups: those with >26 progeny were split into three groups and those with >39 sibs were split into four groups. Partitioning large sibships by units of 10, 11, or 12, rather than 13, had no effect on the estimation of crossover counts, suggesting that the estimates were robust to the unit of subdivision. These subdivided families were used only for haplotype inference; all other analyses treated whole sibships as focal units. In total, we analyzed 132 nonoverlapping sibships, ranging in size from 2 to 48 sibs (mean = 13.9). This data set encompassed 3640 meioses—300–2000% more meioses than previously studied human pedigrees (Broman et al. 1998; Kong et al. 2002; Coop et al. 2008)—providing excellent power to detect recombination rate variation among individuals.

The recombination rate for the maternal (or paternal) parent of a given sibship was estimated as the average number of recombination events in the haploid maternal (or paternal) genomes transmitted to her (or his) offspring. Our analyses treat males and females separately, as previous observations in mice (Murray and Snell 1945; Mallyon 1951; Reeves et al. 1990; Dietrich et al. 1996; Shifman et al. 2006; Paigen et al. 2008), along with findings from this study, point to systematically higher recombination rates in female than in male mice (this study: P < 2.2 × 10−16, Mann–Whitney U-Test comparing autosomal crossover counts in the 131 HS females to those in the 131 HS males).

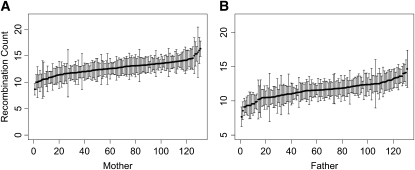

There is considerable recombination rate heterogeneity among the 131 mothers and 131 fathers in the HS pedigrees (Figure 1). The female with the highest recombination rate had an average of nearly twice as many crossovers per meiosis compared with the lowest (female range: 9.0–17.3; mean = 13.3; SD = 3.28). Similarly, the least actively recombining male had only 55% the amount of recombination as the male with the highest recombination rate (male range: 7.7–14.7; mean = 11.7; SD = 2.76). These average values are similar to previously reported recombination counts in house mice, determined using both cytological (Dumas and Britton-Davidian 2002; Koehler et al. 2002) and genetic (Dietrich et al. 1996) approaches. Note that the recombination rates that we report reflect the number of exchange events visible in genetic data. Under the assumption of no chromatid interference, the expected number of crossovers that occur at meiosis is equal to twice these values.

Figure 1.—

Variation in recombination frequency in HS mice. The mean number of recombination events per transmitted gamete in each mother (A; n = 131) and father (B; n = 131) was inferred by comparing parent and offspring genotypes at >10,000 autosomal and X-linked markers using the CRIMAP chrompic computer program. Error bars span ±2 SEs.

To test for variation in recombination within the HS females and within the HS males, we performed a one-way ANOVA using parental identity as the factor and the recombination count for a single haploid genome transmission on the pedigree as the response variable. Significance of the resultant F-statistic was empirically assessed by randomizing parental identity with respect to individual recombination counts, recomputing the F-statistic on the permuted data set, and determining the quantile position of the observed F-statistic along the distribution of 106 F-statistics derived from randomization. There is highly significant variation for genomic recombination rate among HS females (F = 1.7842, P < 10−6; Figure 1A) and males (F = 2.3103, P < 10−6; Figure 1B).

We next examined patterns of recombination rate inheritance using the eight complex families to test for heritability of this trait. We fit a polygenic model of inheritance using the polygenic command within SOLAR v.4, accounting for the uneven relatedness among individuals through a matrix of pairwise coefficients of relatedness (Almasy and Blangero 1998). Sex was included as a covariate in the model to account for the well-established differences between male and female recombination rates in mice (Murray and Snell 1945; Mallyon 1951; Reeves et al. 1990; Dietrich et al. 1996; Shifman et al. 2006; Paigen et al. 2008). Recombination rates show significant narrow-sense heritability (h2 = 0.46; SE = 0.20; P = 0.008), indicating that variation for recombination rate among HS mice is partly attributable to additive genetic variation. This result agrees with previous evidence for genetic effects on recombination rate variation in the house mouse (Reeves et al. 1990; Shiroishi et al. 1991; Koehler et al. 2002).

In summary, we have shown that HS mice differ significantly in their genomic recombination rates and have demonstrated that this variation is heritable. These findings indicate that interstrain variation for genomic average recombination rate exists among at least two of the eight progenitor strains of the HS stock, mirroring observations of significant variation among inbred laboratory strains for many other quantitative characters (Grubb et al. 2009). Indeed, cytological analyses have already revealed significant differences in recombination frequencies between A/J and C57BL/6J males (Koehler et al. 2002), two of the HS founding strains.

This interstrain variation in genomic recombination rate carries important practical implications for genetic analysis in the house mouse. Most notably, crosses using inbred mouse strains with high recombination rates will provide higher mapping resolution than crosses using strains with reduced recombination rates. However, the strategic use of high-recombination-rate strains will not necessarily expedite the fine mapping of loci. The distribution of recombination events in mice is not uniform across chromosomes and appears to be strain specific (Paigen et al. 2008; Grey et al. 2009; Parvanov et al. 2009).

The history of the classical inbred mouse strains as inferred from pedigrees (Beck et al. 2000), sequence comparisons to wild mice (Salcedo et al. 2007), and genomewide phylogenetic analyses (Frazer et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2007) suggests that much of the interstrain variation for recombination rate arises from genetic polymorphism among Mus domesticus individuals in nature. However, many other factors have likely shaped recombination rate variation among the classical strains, including inbreeding, artificial selection, and hybridization with closely related species (Wade and Daly 2005). These aspects of the laboratory mouse's history challenge comparisons between recombination rate variation in the HS panel and human populations and provide strong motivation for studies of recombination rate variation in natural populations of house mice.

Although we find a strong genetic component to inter-individual variation in recombination rate, a large fraction (∼54%) of the phenotypic variation for recombination is not explained by additive genetic variation alone. Sampling error and other forms of genetic variation (e.g., dominance and epistasis) likely combine to account for some of the residual variation. In addition, micro-environmental differences within the laboratory setting (Koren et al. 2002) and life history differences among families, including parental age (Koehler et al. 2002; Kong et al. 2004), might contribute to variation in recombination rates among the HS mice.

Identifying the genetic loci that underlie recombination rate differences among the HS mice (and hence in the eight founding inbred strains) presents a logical next step in the research program initiated here. The complicated pedigree structure, relatively small number of animals with recombination rate estimates (n = 262), and potentially sex-specific genetic architecture of this trait (Kong et al. 2008; Paigen et al. 2008) will pose challenges to this analysis. Nonetheless, dissecting the genetic basis of recombination rate variation is a pursuit motivated by its potential to lend key insights into several enduring questions. Why do males and females differ in the rate and distribution of crossover events? What are the evolutionary mechanisms that give rise to intraspecific polymorphism and interspecific divergence for recombination rate? What are the functional consequences of recombination rate variation? Alternative experimental approaches, including those that combine the power of QTL mapping with immunocytological assays for measuring recombination rates in situ (Anderson et al. 1999), promise to offer additional clues onto the genetic mechanisms that give rise to variation in this important trait.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Flint for helpful feedback.This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM074244 (to K.W.B.) and HG004498 (to B.A.P.) and a National Science Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship (to B.L.D.).

References

- Allard, R. W., 1963. Evidence for genetic restriction of recombination in the lima bean. Genetics 48 1389–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasy, L., and J. Blangero, 1998. Multipoint quantitative trait-linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 62 1198–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L. K., A. Reeves, L. M. Webb and T. Ashley, 1999. Distribution of crossing over on mouse synaptonemal complexes using immunofluorescent localization of MLH1 protein. Genetics 151 1569–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J. A., S. Lloyd, M. Hafezparast, M. Lennon-Pierce, J. T. Eppig et al., 2000. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat. Genet. 24 23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman, K. W., J. C. Murray, V. C. Sheffield, R. L. White and J. L. Weber, 1998. Comprehensive human genetic maps: individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63 861–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman, K. W., L. B. Rowe, G. A. Churchill and K. Paigen, 2002. Crossover interference in the mouse. Genetics 160 1123–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, L. D., and R. W. Marks, 1986. The organization of genetic variation for recombination in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 114 525–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnici, J. P., 1971. Modification of recombination frequency in Drosphila. I. Selection for increased and decreased crossing over. Genetics 69 71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop, G., and M. Przeworski, 2007. An evolutionary view of human recombination. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop, G., X. Wen, C. Ober, J. K. Pritchard and M. Przeworski, 2008. High-resolution mapping of crossovers reveals extensive variation in fine-scale recombination patterns among humans. Science 319 1395–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, A., C. Ackert-bicknell, B. L. Dumont, Y. Ding, J. Tzenova Bell et al., 2009. A new standard genetic map for the laboratory mouse. Genetics 182 1335–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest, K., J. Koyner, J. McCaughran, L. Cipp and R. Hitzemann, 2001. Further characterization and high-resolution mapping of quantitative trait loci for ethanol-induced locomotor activity. Behav. Genet. 31 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewees, A. A., 1975. Genetic modification of recombination rate in Tribolium castaneum. Genetics 81 537–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, W. F., J. Miller, R. Steen, M. A. Merchant, D. Damron-Boles et al., 1996. A comprehensive genetic map of the mouse genome. Nature 380 149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, D., and J. Britton-Davidian, 2002. Chromosomal rearrangements and evolution of recombination: comparison of chiasma distribution patterns in standard and Robertsonian populations of the house mouse. Genetics 162 1355–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, K. A., E. Eskin, H. M. Kang, M. A. Bogue, D. A. Hinds et al., 2007. A sequence-based variation map of 8.27 million SNPs in inbred mouse strains. Nature 448 1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, P., K. Falls and S. Crooks, 1990. CRI-MAP Documentation, version 2.4. http://linkage.rockefeller.edu/soft/crimap.

- Grey, C., F. Baudat and B. de Massy, 2009. Genome-wide control of the distribution of meiotic recombination. PLoS Biol. 7 e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, S. C., T. P. Maddatu, C. J. Bult and M. A. Bogue, 2009. Mouse Phenome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 D720–D730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold, T., and P. Hunt, 2001. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell, M. G., 1972. Genetic change of recombination value in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Artificial selection for high and low recombination and some properties of recombination-modifying genes. Genetics 70 419–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, K. E., J. P. Cherry, A. Lynn, P. A. Hunt and T. J. Hassold, 2002. Genetic control of mammalian meiotic recombination. I. Variation in exchange frequencies among males from inbred mouse strains. Genetics 162 297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, A., D. F. Gudbjartsson, J. Sainz, G. M. Jonsdottir, S. A. Gudjonsson et al., 2002. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat. Genet. 31 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, A., J. Barnard, D. F. Gudbjartsson, G. Thorleifsson, G. Jonsdottir et al., 2004. Recombination and reproductive success in humans. Nat. Genet. 36 1203–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, A., G. Thorleifsson, H. Stefansson, G. Masson, A. Helgason et al., 2008. Sequence variants in the RNF212 gene associate with genome-wide recombination rate. Science 319 1398–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren, A., S. Ben-Aroya and M. Kupiec, 2002. Control of meiotic recombination initiation: A role for the environment? Curr. Genet. 42 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E. S., and P. Green, 1987. Construction of multilocus genetic linkage maps in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84 2363–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallyon, S. A., 1951. A pronounced sex difference in recombination values in the sixth chromosome of the house mouse. Nature 168 118–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott, R., C. J. Talbot, M. G. Turri, A. C. Collins and J. Flint, 2000. A method for fine-mapping quantitative trait loci in outbred animal stocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 12649–12654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. M., and G. D. Snell, 1945. Belted, a new sixth chromosome mutation in the mouse. J. Hered. 36 266–268. [Google Scholar]

- Paigen, K., J. P. Szatkiewicz, K. Sawyer, N. Leahy, E. D. Parvanov et al., 2008. The recombinational anatomy of a mouse chromosome. PLoS Genet. 4 e1000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvanov, E., S. H. S. Ng, P. M. Petkov and K. Paigen, 2009. Trans-regulation of mouse meiotic recombination hotspots by Rcr1. PLoS Genet. 7 e1000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, R. H., M. R. Crowley, B. F. O'Hara and J. D. Gearhart, 1990. Sex, strain, and species differences affect recombination across an evolutionary conserved segment of mouse chromosome 16. Genomics 8 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo, T., A. Geraldes and M. W. Nachman, 2007. Nucleotide variation in wild and inbred mice. Genetics 177 2277–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D. D., 1972. Genetic and environmental components of chiasma control. I. The response to selection in Schistocerca. Chromosoma 37 297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman, S., J. Tzenova Bell, R. R. Copley, M. S. Taylor, R. W. Williams et al., 2006. A high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism genetic map of the mouse genome. PLoS Biol. 4 e395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiroishi, T., T. Sagai, N. Hanzawa, H. Gotoh and K. Moriwaki, 1991. Genetic control of sex-dependent meiotic recombination in the major histocompatibility complex of the mouse. EMBO J. 10 681–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdar, W., L. C. Solberg, D. Gauguier, S. Burnett, P. Klenerman et al., 2006. Genome-wide genetic association of complex traits in heterogeneous stock mice. Nat. Genet. 38 879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade, C. M., and M. J. Daly, 2005. Genetic variation in laboratory mice. Nat. Genet. 37 1175–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H., T. A. Bell, G. A. Churchill and F. Pardo-Manuel de Villena, 2007. On the subspecific origin of the laboratory mouse. Nat. Genet. 39 1100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]