Dear Editor,

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare disease, characterised by thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. Under normal circumstances, unusually large multimers (UL) of von Willebrand factor (VWF) are released by activated endothelial cells and subsequently rapidly proteolysed by ADAMTS-13 into smaller, less active forms. In TTP, the released ULVWF persist in the circulation due to a lack of ADAMTS-13, prompting the formation of micro-thrombi and micro-vascular obstruction [1]. Although the primary defect underlying TTP is presumed to be a deficiency of ADAMTS-13, the deficiency on its own seems not sufficient for the disease to become clinically apparent [2].

In an attempt to gain more insight into the mechanism of TTP, we recently evaluated ADAMTS-13 activity and plasma VWF multimer distribution patterns, expressed as VWF:Collagen binding/VWF:Antigen (VWF:CB/VWF:Ag) ratio, in relation to platelet treatment–response patterns during the first 14 days of plasma exchange (PE) in 26 disease episodes in 21 patients with idiopathic TTP consecutively admitted at our institution from 1994 to 2006. The observations are explained in a model in which acute thrombotic episodes in TTP are triggered by a mechanism of platelet activation besides endothelial cell activation.

All patients followed a uniform treatment scheme including daily plasma exchange (PE) with fresh frozen plasma replacement (50 ml/kg/day) in combination with prednisone 1.5 mg kg/day/p.o. for 2–3 weeks followed by a tapering scheme of 10 mg reduction per 2 days to stop. After normalisation of the platelet count (>140 × 109/l for three consecutive days), PE was tapered to stop within 2 weeks (first week 3 and second week 2 PE's). Patients' informed consent was obtained at a recent outpatient visit or by telephone if discharged from follow-up. ADAMTS-13 activity (detection limit 3%) was measured as described [3, 4]. Anti-ADAMTS-13 IgG auto-antibodies were detected with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (American Diagnostica Inc., Stamford CT, USA, normal range 2.1–12.8, mean 7.2, SD 3.6, n = 9) and in some cases with mixing experiments. VWF:Ag and VWF:CB were measured with an in-house sandwich ELISA [5, 6]. For analysis of the proteolytic fragments of VWF, blood samples were reduced, separated by gel electrophoresis and visualised as described [7, 8]. IgG (MW 150 kD) and IgE (MW 196 kD), visualised in untreated plasma, were used as internal molecular weight standards by identification of the VWF fragments. The relative amount of the proteolytic VWF fragments was measured using Image Quant 5.2 by calculating the area under the peak. The biological variability between normal donors for the 225-kD VWF subunit, the 176- and 189-kD proteolytic fragments was 80.0 ± 6.3%, 17.8 ± 6.3% and 1.6 ± 0.9%, respectively (n = 14).

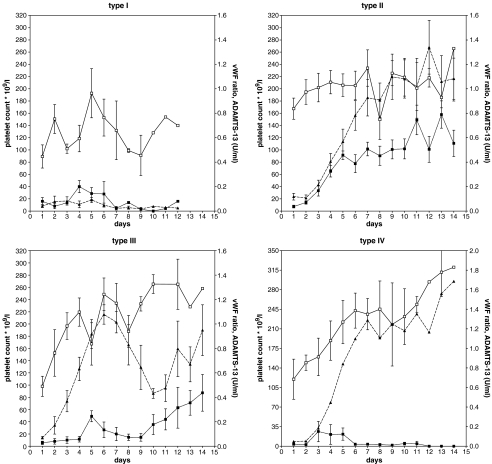

Four different platelet–treatment response patterns were discerned (types I–IV, Table 1 and Fig. 1). Of special interest are the response patterns II and III which can be distinguished by a normal VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio and a normal amount (as determined in three patients) of the 176-kD proteolytic VWF fragments in type II from that of type III with a reduced VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio and increased amounts (37.1 ± 20.0%, n = 3) of 176-kD VWF cleavage fragments at diagnosis. The increased amount of the 176-kD VWF cleavage fragments points to increased proteolysis of VWF by ADAMTS-13 [9]. Type IV is distinguished from types II and III by persistently decreased ADAMTS-13 due to the presence of auto-antibodies.

Table 1.

Platelet treatment–response types in relation to ADAMTS-13 activity and plasma von Willebrand factor (VWF) multimer distribution (expressed as VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio) in 26 disease episodes of idiopathic TTP

| Platelet response type | Number of episodesa | Days to platelets >140 × 109/l (from start PE, median, range) | Disease outcome | ADAMTS13 activity (%), mean (range) at | VWF ratio mean (range) at | Anti-ADAMTS13 IgG (μg/ml), mean (range) at | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Platelets >140 × 109/lb | Diagnosis | Diagnosis | Platelets >140 × 109/lb | ||||

| I | 4 | n.a. | All patients died of refractory disease on median day 9 from start PE | <10 (<3–9) | n.a. | 0.49 (0.26–0.54) | 196 (18–434) | 31 (14–62) |

| II | 13 | 7 (5–30) | Remissiond | <10 (<3–10) | 52 (25–113) | 0.89 (0.28–1.44) | 134 (11–800) | 16 (11–26) |

| III | 6 | 5 (3–6) | Remissiond preceded by a short-lasting normalisation of the platelet counte | <10 (<3–5) | 13 (4–29) | 0.48 (0.27–0.65) | 47 (31–61) | 21 (13–30) |

| IV | 3 | 5 (2–8) | Remissionf | <3 | <10 | 0.75 (0.48–0.89) | 51 (42–59) | Presentgh |

n.a. not applicable, PE plasma exchange

aTwenty-one episodes are newly diagnosed and five are first relapses, all occurring after a relapse-free interval of ≥1 year

bData represent the mean of two or three measurements on the first three consecutive days of platelets >140 × 109/l

cAnti-ADAMTS13 IgG levels in last plasma sample before death

dContinuing during follow-up of ≥1 year

eShort-lasting normalisation of the platelet count: platelets >140 × 109/l for≤10 days

fIn two episodes lasting >1 year, in one episode relapse after 6 months

gPersisting during follow-up of ≥1 year

hMeasured as anti-ADAMTS13 inhibitory activity

Fig. 1.

Mean values of ADAMTS-13 activity (filled square), VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio (empty square) and platelet count (filled triangle) during the first 2 weeks from the start of PE in four different treatment–response types in 26 treatment episodes in 21 patients with idiopathic TTP

The treatment of type I patients was unsuccessful without normalisation of the platelet count, ADAMTS-13 activity and VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio. In types II, III and IV patients, platelet counts rose rapidly after initiation of treatment, eventually resulting in continuing remissions during the follow-up period of ≥1 year. Two of the five relapse episodes (all being first relapses occurring after a relapse-free interval of ≥1 year) showed the same response pattern as before whereas in the other three relapse episodes, a different response pattern was observed. Remarkably, durable remissions in type III responses were preceded by a short-lasting normalisation of the platelet count (>140 × 109/l) during which ADAMTS-13 activity was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than in type II responses at the same stage of treatment. The occurrence of an early drop in platelet count in type III might have been triggered by the tapering (according to protocol) of PE at a moment when the platelet count was already restored but ADAMTS-13 activity was still very low. This may implicate a need for prolonging PE treatment in patients in whom a type III response pattern is identified.

The significant correlation (Pearson R2 = 0.9289, P = 0.0019) between the rise of the (log) platelet count and the increase of ADAMTS-13 activity which was noticed in type II during the first 6 days of PE treatment (Fig 1), suggests decreasing microthrombi formation, thereby supporting the model in which ADAMTS-13 directly regulates the formation of micro-thrombi [10]. In contrast, during the first 6 days of treatment in type III, the rise of the (log) platelet count did not correlate with the ADAMTS-13 activity but was significantly correlated with the rise of the VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio (Pearson, R2 = 0.7269, P = 0.031). The response pattern suggests that in type III, PE primarily influences the interaction between VWF and platelets, rather than that it supplies deficient or non-functional ADAMTS-13.

Regarding the mechanism of the different treatment–response patterns in types II and III, one can only speculate. Key roles seem to be reserved for activation of the endothelial cell (type II) or the platelets (type III). Endothelial cell activation stimulates excretion of ULVWF, thereby promoting shear dependent micro-thrombi formation by VWF–platelet GPIbα interaction. This process is independent of platelet activation but is enhanced by reduced proteolytic degradation of the ULVWF multimers because of deficient ADAMTS-13 activity [1]. By consequence, no excess of VWF proteolytic fragments is detected, as was the case in the type II responses that were examined.

Micro-thrombi may also be formed as the result of interaction of plasma VWF with platelet GPIIb/IIIa (αIIbβ3), activated by still unknown factors. Insufficient feedback of microthrombi formation by plasma ADAMTS-13, which has been shown to affect the size of microthrombi, may cause microvascular thrombosis of TTP [11]. Type III (and possibly also types I and IV) responses are examples of increased interaction of plasma VWF with platelets. Platelet-ADAMTS-13 which is released after platelet activation and which is less susceptible to inhibition by plasma anti-ADAMTS-13 antibodies [12, 13], might elicit low-grade degradation of VWF-thrombi as shown by an increase of 176-kD proteolytic VWF fragments in plasma in the examined cases.

Whether these or other mechanisms, besides lack of ADAMTS-13 activity, play a role in triggering clinical manifestations of TTP remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Lämmle B, Kremer Hovinga JA, Alberio L (2005) Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost 3:1663–1675. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01425.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Desch KC, Motto DG (2007) Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in humans and mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27:1901–1908. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145797 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gerritsen HE, Turecek PL, Schwarz HP, Lämmle B, Furlan M (1999) Assay of von Willebrand factor (vWF)-cleaving protease based on decreased collagen binding affinity of degraded vWF: a tool for the diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Thromb Haemost 82:1386–1389 [PubMed]

- 4.Loof A, van Vliet HHDM, Kappers-Klunne MC (2001) Low activity of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease is not restricted to patients suffering from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol 112:1087–1088. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02622-5.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cejka J (1982) Enzyme immunoassay for FVIII-related antigen. Clin Chem 28:1356–1358 [PubMed]

- 6.Brown JE, Bosak JO (1986) An ELISA test for the binding of von Willebrand factor antigen to collagen. Thromb Res 43:303–311. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(86)90150-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Brosstad F, Kjonniksen I, Ronning B, Stormorken H (1986) Visualization of von Willebrand factor multimers by enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies. Thromb Haemost 55:276–278 [PubMed]

- 8.Fisher BE, Thomas KB, Schlokat U, Dorner F (1998) Triplet structure of human von Willebrand factor. Biochem J 331:483–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Dent JA, Berkowitz SD, Ware J, Kasper CK, Ruggeri ZM (1990) Identification of a cleavage site directing the immunochemical detection of molecular abnormalities in type IIA von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:6306–6310. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.16.6306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dong JF, Moake JL, Nolasco L, Bernardo A, Arceneaux W, Shrimpton CN, Schade AJ, McIntire LV, Fujikawa K, López JA (2002) ADAMTS-13 rapidly cleaves newly secreted ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers on the endothelial surface under flowing conditions. Blood 100:4033–4039. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-05-1401 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Donadelli R, Orje JN, Capoferri C, Remuzzi G, Ruggeri ZM (2006) Size regulation of von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet thrombi by ADAMTS13 in flowing blood. Blood 107:1943–1950. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-07-2972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Suzuki M, Murata M, Matsubara Y, Uchida T, Ishihara H, Shibano T, Ashida S, Soejima K, Okada Y, Ikeda Y (2004) Detection of von Willebrand factor cleaving protease (ADAMTS-13) in human platelets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313:212–216. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.111 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Liu L, Choi H, Bernardo A, Bergeron AL, Nolasco L, Ruan C, Moake JL, Dong JF (2005) Platelet-derived VWF-cleaving metalloprotease ADAMTS-13. J Thromb Haemost 3:2536–2544. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01561.x [DOI] [PubMed]