Abstract

Binding of type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) to cell surface urokinase (uPA) promotes inactivation and internalization of adhesion receptors (e.g., urokinase receptor (uPAR), integrins) and leads to cell detachment from a variety of extracellular matrices. In this report, we begin to examine the mechanism of this process. We show that neither specific antibodies to uPA, nor active site inhibitors of uPA, can detach the cells. Thus, cell detachment is not simply the result of the binding of macromolecules to uPA and/or of the inactivation of uPA. We further demonstrate that another uPA-inhibitor, protease nexin-1 (PN-1), also stimulates cell detachment in a uPA/uPAR-dependent manner. The binding of both inhibitors to uPA leads to the specific inactivation of the matrix-engaged integrins and the subsequent detachment of these integrins from the underlying extracellular matrix (ECM). This inhibitor-mediated inactivation of integrins requires direct interaction between uPAR and those integrins since cells attached to the ECM through integrins incapable of binding uPAR, do not respond to the presence of either PAI-1 of PN-1. Although both inhibitors initiate the clearance of uPAR, only PAI-1 triggers the internalization of integrins. However, cell detachment by PAI-1 or PN-1 does not depend on the endocytosis of these integrins since cell detachment was also observed when clearance of these integrins was blocked. Thus, PAI-1 and PN-1 induce cell detachment through two slightly different mechanisms that affect integrin metabolism. These differences may be important for distinct cellular processes that require controlled changes in the subcellular localization of these receptors.

Keywords: cell detachment, urokinase receptor, integrins, PAI-1, protease nexin-1, endocytosis

INTRODUCTION

The urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA):plasmin system has been implicated in the migration and invasion of cells (Andreasen et al, 2000), possibly because uPA binds to a receptor (uPAR; CD 87) on the cell surface where it catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin (Kjoller, 2002). However, the binding of uPA to uPAR also alters the conformation of the receptor (Mondino et al, 1999), and these changes in uPAR itself promote cell adhesion to vitronectin (VN) (Wei et al, 1994;Mondino et al, 1999;Wei et al, 2001)), lead to the formation of stable complexes between the receptor and a variety of integrins (Chapman and Wei, 2001;Tarui et al, 2001;Czekay et al, 2003), and induce the activation of signaling molecules important for uPA-induced cell migration ((Xue et al, 1997;Tang et al, 1998;Yebra et al, 1999;Nguyen et al, 2000;Nguyen et al, 1999;Aguirre Ghiso et al, 1999). The binding of uPA to uPAR may also modify the interaction between integrins and the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Wei et al, 2005). Thus, the uPA system not only mediates cell surface proteolysis but also may regulate cell adhesion and motility (for reviews see (Ossowski and Aguirre-Ghiso, 2000;Kjoller, 2002;Stefansson and Lawrence, 2003;Czekay and Loskutoff, 2004)).

The main physiological inhibitor of uPA is plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (reviewed in (Czekay and Loskutoff, 2004)). The binding of PAI-1 to receptor-bound uPA inactivates the uPA, and the resulting PAI-1:uPA:uPAR complexes are rapidly internalized by members of the LDL receptor gene family (i.e., LDL receptor-related protein; LRP (Nykjær et al, 1997;Heegaard et al, 1995;Czekay et al, 2001;Prager et al, 2004). It is now clear that PAI-1 also induces the internalization of integrins that are bound to uPAR, and that it does so through a similar LRP-dependent process (Czekay et al, 2003). The internalized receptors subsequently recycle back to the cell surface (Nykjær et al, 1997;Woods et al, 2004;Powelka et al, 2004), while PAI-1 and uPA are degraded.

Vitronectin is relatively unique among ECM proteins because cells can attach to it both through integrins and through uPAR (Wei et al, 1994;Deng et al, 1996), and because it binds to and stabilizes PAI-1 (Seiffert et al, 1994). The high affinity binding site for PAI-1 was localized to the somatomedin B (SMB) domain of VN (Seiffert et al, 1994). This site overlaps with the binding site for uPAR (Okumura et al, 2002), and both sites are adjacent to the single RGD sequence (i.e., integrin binding site) in the molecule. Because of its higher affinity for VN, PAI-1 can competitively block both uPAR- and integrin-dependent attachment of cells to VN (Deng et al, 1996;Deng et al, 2001;Stefansson and Lawrence, 1996;Kjoller et al, 1997;Waltz et al, 1997). The inhibitor can also competitively displace uPAR from VN, and thus can detach cells from this ECM if they are attached through uPAR alone (e.g., U937 cells; (Deng et al, 1996)). We recently demonstrated that PAI-1 also can detach cells from VN if they are bound to it through integrins (Czekay et al, 2003). In this case, the binding of PAI-1 to uPA:uPAR:integrin complexes on the cell surface somehow leads to the inactivation of VN-specific integrins (i.e., αVβ3, αVβ5) and their endocytic clearance by LRP. This PAI-1-mediated process also initiates cell detachment from a variety of other ECM proteins (i.e., fibronectin (FN), Type-1 collagen, etc.). The deadhesive properties of PAI-1 may decrease the adhesive strength of tumor cells and thus begin to explain why high PAI-1 levels are frequently associated with a poor prognosis in human metastatic disease (Foekens et al, 2000).

In this report, we examine the specificity of these deadhesive effects of PAI-1, and we investigate the role of integrin inactivation and clearance in this process. We show that another uPA inhibitor, protease nexin-1 (PN-1) can also detach cells from the ECM in a uPA/uPAR-dependent manner, and we provide evidence that cell detachment by both PAI-1 and PN-1 only depends on the selective inactivation of matrix-engaged integrins; it does not require their clearance. We provide further evidence that direct interaction between uPAR and integrins is required for the deadhesive effects of these uPA inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Protein G-agarose and Percoll were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ) and Biotin-XX was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon). Porcine trypsin, soy bean trypsin inhibitor, and CHAPS (3-[(3-chloromidopropyl) dimethylammunio]-1-propanesulfonate) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The BCA Protein Assay and the ECL detection system were from Pierce (Rockford, IL), and the ABC kit for detecting biotinylated proteins was from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from HyClone (Logan, UT), RPMI and DME cell culture medium were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, California), and pAPMSF (p-amidinophenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) was from EMD Biosciences (La Jolla, CA). All other chemicals and buffers were of the highest analytical grade available.

Proteins

Active two-chain uPA (human) was purchased from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT), while soluble human uPAR was a gift from Dr. Douglas Cines (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The recombinant stable active form of PAI-1 (14-1b, (Berkenpas et al, 1995)) was expressed and purified as previously described (Kamikubo et al, 2002), and a mutant form of PAI-1 (R76→E) which binds normally to uPA but poorly to LRP (Stefansson et al, 1998), was supplied by Dr. Dan Lawrence (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). PN-1 was a gift from Dr. Denis Monard (Friedrich-Miescher Institute, Basel Switzerland). Receptor-associated protein (RAP) was expressed and purified as a GST fusion protein (Herz et al, 1991), while VN was purified from human plasma (Yatohgo et al, 1988). Human FN was purchased from Becton Dickinson Labware (Franklin Lakes, NJ)). A recombinant, biotinylated fragment of FN consisting of the three type-III repeats (bFN9/11) (Ramos and DeSimone, 1996) was a gift from Dr. Mark Ginsberg (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA). Serum-free conditioned medium containing heterotrimeric laminin-5 (LN-5) (Goldfinger et al, 1998), as well as a 17-mer α3β1 integrin-derived peptide (a325; (Wei et al, 2001)) and an inactive, scrambled variant of this peptide (sca325) were all gifts from Dr. Harold Chapman (University of California at San Francisco, CA).

Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against human αVβ5 (P1F6) and α3β1 (MAB1992) integrins were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). The function blocking mAb against human α5β1 integrin (PB-1) was a gift from Dr. Mark Ginsberg, while polyclonal antibodies (pAb) against a recombinant soluble fragment of human uPAR (i.e., uPAR1-274) and against human LRP, were supplied by Dr. Marilyn Farquhar (University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA). An activity blocking mAb (#394) against the human uPA B-chain, a non-inhibitory mAb against human uPA (#3689), and a mAb (#3936) against human uPAR were from American Diagnostica (Stamford, CT).

Methods

Cell culture

The human fibrosarcoma cell line (HT-1080) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and cultured in DME supplemented with 10% FBS as previously described (Czekay et al, 2001). Two mouse kidney epithelial cell lines deficient in α3-integrin expression were provided by Dr. Harold Chapman. The first was transfected with both human uPAR and human α3-integrin, while the second was transfected with human uPAR and a mutant form of human α3-integrin (α3H245A) (Wang et al, 2001;Zhang et al, 2003). Both cells lines were cultured in DME medium as described (Zhang et al, 2003).

Acid treatment of cells

Unless otherwise indicated, cultured cells were acid-treated (Cubellis et al, 1989;Czekay et al, 2003) to remove endogenous uPA from uPAR, thus making available a more consistent pool of surface uPAR for subsequent binding studies. Briefly, the cells were incubated in glycine buffer at pH 4.0 for 3 min at 4°C, and then neutralized by incubation in 0.05 M TRIS buffer at pH 7.4 for 10 min at 4°C. The acid-treated cells were washed twice in RPMI medium and then employed in the various assays. They responded to the addition of uPA plus various inhibitors in a similar but more dramatic manner compared to control cells which were not acid washed (Czekay et al, 2003).

Cell detachment and reattachment experiments

To perform cell detachment experiments, microtiter plates were coated with 100 μl of various ECM proteins including VN (5 μg/ml), FN (5 μg/ml), and LN-5 containing conditioned medium (diluted 1:100 in PBS) for 18 h at 4°C. After blocking the wells by incubating them in 7.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 2 h at room temperature, cells (1.5×105) in RPMI containing 20 mM Hepes and 0.02% BSA (RPMI/BSA) were added to each well and allowed to attach for 1.5 h at 37°C. The monolayers were acid-treated as described above, and then incubated in the absence or presence of uPA (50 nM) for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound uPA was removed by washing in RPMI/BSA at 4°C, and then the inhibitors (i.e., either PAI-1 or PN-1; all at 40 μg/ml) were added to the cells for 30 min at 4°C in RPMI/BSA. In some cases, additional molecules (e.g., PAI-1R76E, anti-LRP IgG, pAPMSF, synthetic peptides, or the IgG fraction of various antibodies to uPA) were added as indicated together with uPA at 4°C. The microtiter plates were incubated for 5 min at 37°C, agitated twice for 1 min (Molecular Devices Vmax Plate Reader) at room temperature and then gently washed with PBS. The number of cells that remained attached to the wells after these treatments were analyzed by quantitation of crystal violet staining (Czekay et al, 2003).

To perform reattachment experiments, the cells were detached from either FN or LN-5 coated culture dishes, washed by centrifugation at 4°C, and then allowed to reattach to LN-5 coated 96-well microtiter plates at 4°C. The extent of reattachment was determined by crystal violet staining.

Binding of biotinylated FN9/11 to cells in suspension

HT-1080 cells (1.5×105) in RPMI/BSA were added to FN or LN-5 coated wells and allowed to attach for 1.5 h at 37°C. The monolayers were acid-treated, and then the cells were detached by sequential incubation with uPA and either PAI-1 or PN-1 in RPMI/BSA at 4°C as described above. Control cells, treated in parallel with buffer or with uPA alone, were released by incubation with trypsin (0.25%) at 4°C, washed, and then incubated with 0.25% soy bean trypsin inhibitor for 5 min to neutralize the trypsin. All detached cells were washed by centrifugation and then incubated with biotinylated FN9/11 (bFN9/11) for 1 h at 4°C in the absence or presence of MnCl2 (2 mM). In some experiments, the cells were incubated with MnCl2 in the presence of a mAb against α5β1 (PB-1; 10 μg/ml). In all cases, the cells were washed in RPMI/BSA, extracted into detergent (10 mM CHAPS), and then fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Biotinylated FN9/11 was detected in blotting experiments using the ABC kit followed by ECL. The amount of cell bound bFN9/11 was determined by densimetric analysis of the exposed films.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cell lysates were prepared by extracting cells into 10 mM CHAPS in buffer HB (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2). The cell lysates were then incubated for 18 h at 4°C in the presence of protein G-agarose beads together with the IgG fraction of mAbs against either αVβ5 (P1F6; 3 μg/ml), α3β1 (MAB1992; 3 μg/ml) or uPAR (#3936; 3 μg/ml). The beads were washed, extracted into reducing sample buffer, and then the extracts were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-uPAR pAb as described previously (Czekay et al, 2001). Biotinylated proteins were detected as above.

Internalization of integrins and uPAR

Acid washed and surface biotinylated HT-1080 cells (Czekay et al, 2001) were incubated with uPA (50 nM) for 1 h at 4°C, washed with RPMI, and then incubated in RPMI/BSA in the presence of either PAI-1 or PN-1 (all at 40 μg/ml) for 1 h at 18°C. Incubation at 4°C prevents the internalization of surface proteins, whereas incubation at 18°C allows surface derived proteins to be internalized and accumulate in early endosomes (EE). In some cases, the incubations were performed in the presence of blocking antibodies against LRP (200 μg/ml). The treated cells were then subjected to cell fractionation by centrifugation at 4°C through 20% Percoll (Czekay et al, 2001). Gradient fractions containing plasma membranes (PM) or EE were pooled separately, and then analyzed for the presence of biotinylated αVβ5, α3β1, and uPAR by immunoprecipitation as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Unless indicated otherwise, results are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three different experiments done in duplicate or triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t tests. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Specificity of cell detachment

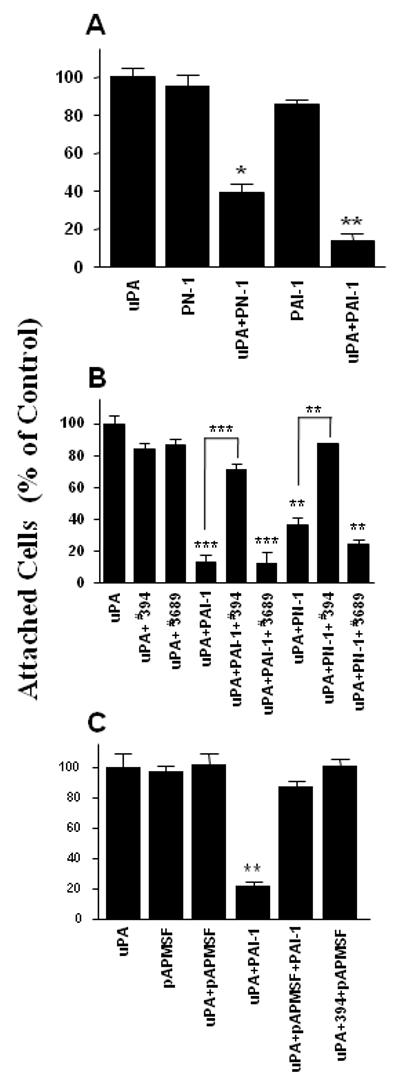

We previously showed that PAI-1 can initiate the detachment of several cell types from a variety of ECM proteins, and that this activity depends on the binding of the inhibitor to uPA on the cell surface (Czekay et al, 2003). Experiments were performed to determine whether PN-1, another uPA inhibitor, could also initiate cell detachment from the ECM (Fig. 1). Control experiments revealed that little or no detachment was observed when the cells were incubated with PN-1 alone compared with the control cells treated with uPA alone (Fig. 1A). However, if the cells were first preincubated with uPA, the subsequent addition of PN-1 (or PAI-1) resulted in the detachment of a significant number of cells. Thus, PAI-1 is not unique in its ability to initiate cell detachment.

Figure 1.

Effect of various uPA inhibitors on cell detachment from VN. HT-1080 cells were seeded onto VN-coated wells in serum-free medium for 1.5 h, acid washed, and then incubated as indicated. In some experiments, the cells were incubated with uPA alone, or with uPA followed by PAI-1 or PN-1 (Panel A), either in the absence or presence of inhibitory (#394) or non-blocking (#3689) mAbs against uPA (Panel B), or in the absence or presence of pAPMSF (Panel C). After incubation, the wells were vigorously agitated, the floating cells were removed by washing, and the number of remaining attached cells was determined. Each column is expressed as a percentage of control (acid washed plus uPA; 100%) ± SD. Statistical differences were measured by comparison with cells only incubated with uPA. In Panel B, cells incubated with uPA+inhibitor were also compared to cells exposed to inhibitor+antibodies. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

PAI-1 and PN-1 bind to uPA and irreversibly inhibit its active site. Since both inhibitors also initiate cell detachment, we performed experiments to determine whether cell detachment requires the inactivation of the uPA. Thus, we examined the deadhesive properties of two mAbs directed against different epitopes in uPA. The first (#394) is a function blocking antibody which binds to an epitope close to the active site in uPA (Kobayashi et al, 1994). The second is a non-blocking antibody (#3689) which binds to uPA at a site distant from its active center. Figure 1B shows that neither antibody was able to detach the uPA-pretreated cells. However, the neutralizing mAb #394 (but not mAb #3689) did prevent PAI-1 and PN-1 from subsequently detaching the cells. This last observation demonstrates that the neutralizing antibody had bound to the uPA on the cell surface and blocked access of the inhibitors to the active site. Although not shown, ELISA experiments demonstrated that the neutralizing mAb also prevented the binding of PAI-1 and plasminogen to uPA. Taken together, these observations indicate that cell detachment in this system is not simply induced by protein:protein interaction with uPA per se but requires the binding of specific proteins, e.g. its inhibitors PAI-1 and PN-1) to the active site in uPA.

Experiments were performed to test the hypothesis that the critical step in the inhibitor-mediated cell detachment process is the irreversible inactivation of the uPA bound to its receptor on the cell surface. In these experiments, the effect of pAPMSF (a compound that irreversibly inhibits serine proteases (e.g., uPA) by binding directly to their active center (Laura et al, 1980)) on cell detachment was evaluated. Figure 1C shows that the addition of pAPMSF to uPA-treated cells did not promote cell detachment. Thus, inhibition of the active site of uPA is, in itself, not sufficient to detach cells. The observation that the pAPMSF-treated cells could no longer be detached by PAI-1 (Fig. 1C) or PN-1 (not shown) indicates that the uPA on the cell surface was indeed inactivated by this treatment and thus was no longer available for the inhibitors. Finally, no cell detachment was observed when uPA-pretreated cells were incubated with both pAPMSF and the blocking mAb (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these observations raise the possibility that the ability to detach cells may be a unique property of these uPA inhibitors.

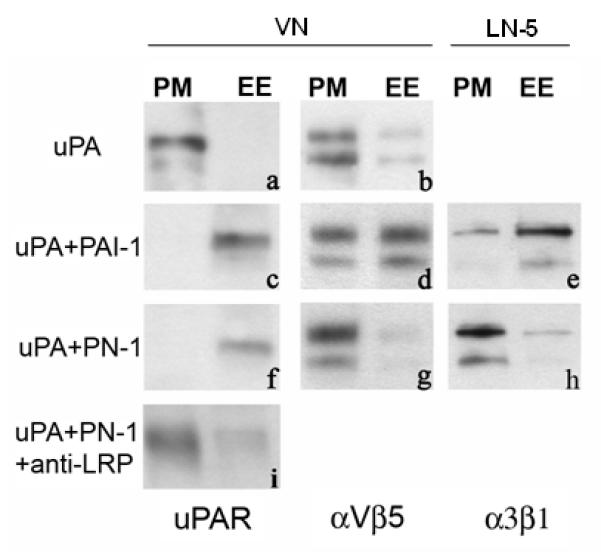

Effect of PN-1 on the subcellular localization of uPAR and integrins

We previously demonstrated that the PAI-1-initiated detachment of cells from VN was associated with the internalization of uPAR and integrins (i.e., αVβ3 and αVβ5) into EE by LRP (Czekay et al, 2003). Experiments were performed to determine whether cell detachment by PN-1 is also associated with the endocytosis of these adhesion receptors into EE. To address this question, surface biotinylated, uPA-pretreated HT-1080 cells were incubated with PN-1 or PAI-1 for 1 h at 18°C. Cell lysates were prepared and fractionated on Percoll gradients, and the fractions containing the PMs and EE were analyzed for the presence of biotinylated uPAR and integrins. Figure 2 shows that when the cells were incubated with uPA alone, the majority of the biotinylated uPAR (panel a) and αVβ5 (panel b) was detected in PM containing fractions. Thus, these adhesion receptors remain at the cell surface following treatment with uPA alone. In agreement with our previous studies (Czekay et al, 2003), subsequent addition of PAI-1 to the uPA pretreated cells induced a significant shift of both molecules from the PM into the EE (panels c, d). Unexpectedly, although PN-1 also detached the cells (Fig. 1) and induced a shift of uPAR from PM into EE (Figure 2, panel f), it did not initiate the internalization of αVβ5 (panel g). The PN-1-induced endocytosis of uPAR appears to be mediated by LRP since a polyclonal antibody that blocks the binding of uPA-inhibitor complexes to LRP (Czekay et al, 2003) also blocked the PN-1 mediated clearance of uPAR (Fig. 2, panel i).

Figure 2.

Effect of uPA inhibitors and anti-LRP antibodies on subcellular distribution of uPAR and αVβ5 and α3β1 integrins. HT-1080 cells were acid washed, surface biotinylated, and incubated as indicated with uPA for 1 h at 4°C either alone, or followed by incubation (1 h, 18°C) with either PAI-1, PN-1 or blocking anti-LRP pAbs. Postnuclear supernatants were prepared and fractionated by centrifugation. Fractions containing either plasma membrane (PM) or early endosomes (EE) were pooled, and pooled fractions were analyzed for the presence of biotinylated αVβ5 or α3β1 integrins or uPAR by immunoprecipitation and blotting as described in Methods.

Although both PAI-1 and PN-1 can initiate the LRP-mediated endocytic clearance of uPAR from the cell surface, only PAI-1 can initiate the endocytic clearance of integrins by LRP (Fig. 2). However, these differences between PAI-1 and PN-1 are not unique to VN-specific integrins. We performed experiments in which HT-1080 cells were cultured on LN-5-coated wells, and thus engaged the matrix predominantly through α3β1 integrins. When these cells were incubated with uPA alone, uPAR and integrins remained at the cell surface (data not shown). However, when they were incubated subsequently with uPA and PAI-1, the majority of the biotinylated uPAR (not shown) and α3β1 (Fig. 2, panel e) was shifted into EE. In contrast, when PN-1 was added to the uPA pretreated cells, uPAR was shifted into EE (not shown) but α3β1 was not (Fig. 2, panel h).

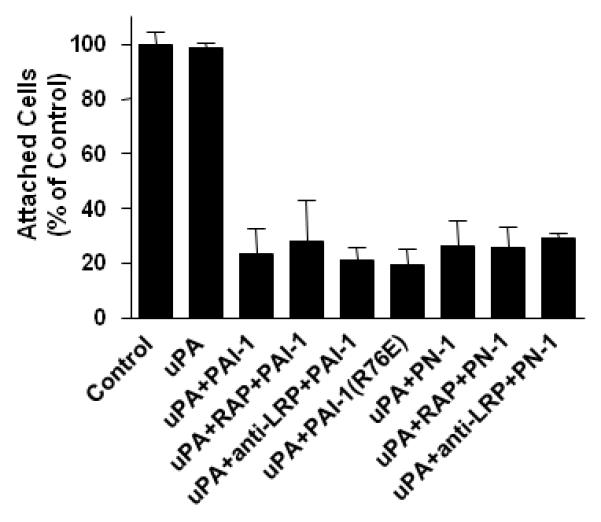

Endocytosis of uPAR:integrin complexes is not required for cell detachment

The observation that PN-1 detaches cells from the ECM but does not cause the internalization of integrins, raises the possibility that endocytosis of adhesion receptors may not be required for cell detachment by PAIs. Figure 3 suggests that this is the case. For example, the cells were still detached by PAI-1 and PN-1 when the experiment was performed in the presence of molecules previously shown to block the binding of the uPA:PAI-1 (Czekay et al, 2001) and uPA:PN-1 (Conese and Blasi, 1995) complexes to LRP (i.e., RAP; inhibitory antibodies). The cells were also detached when the non-LRP-binding form of PAI-1 (i.e., PAI-1R76E) was employed (Fig. 3), even though PAI-1R76E did not induce endocytosis of uPAR and integrins into EE (data not shown). Taken together, these observations demonstrate that the actual clearance of uPAR and integrins (i.e., αVβ5) is not required for cell detachment by uPA inhibitors.

Figure 3.

LRP mediated endocytosis is not required for cell detachment by uPA inhibitors. HT-1080 cells attached to VN-coated wells were incubated sequentially with uPA and then either PAI-1, PAI-1(R76E), or PN-1 in the absence or presence of RAP or anti-LRP pAb. The wells were vigorously agitated, and the remaining attached cells were quantitated as described (see Methods). Each column is expressed as a percentage of control (acid washed only; 100%) ± SD. Statistical analysis revealed that in all experiments the results were significantly (P<0.05) different when compared to cells treated with uPA alone.

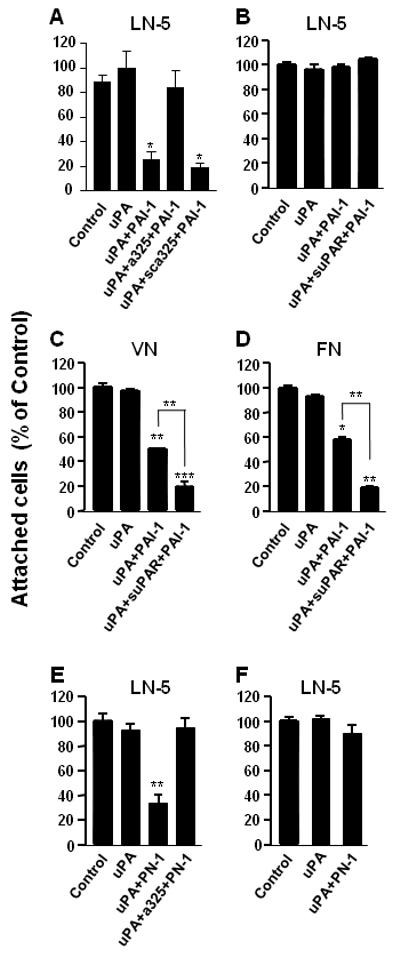

The interaction between uPAR and integrins is required for cell detachment

The observation that the LRP-mediated clearance of adhesion receptors is not required for cell detachment (Fig. 3) raised the possibility that the binding of uPA:uPAR complexes to integrins might not be required as well. To address this possibility, we took advantage of a peptide (a325), which has the same sequence as the binding site in α3 integrins recognized by uPAR. This peptide was previously shown to block the binding of uPA:uPAR complexes to α3 integrins (Wei et al, 2001). In this experiment (Fig. 4), mouse kidney epithelial cells expressing human α3 integrins and human uPAR were allowed to attach to LN-5. Under these conditions, the matrix should be specifically engaged by the α3β1 integrins expressed by these cells (Xue et al, 1997). After acid washing the cells, they were incubated with uPA and PAI-1 in the presence or absence of a325 or its scrambled form. As shown in Fig. 4A, the active peptide completely blocked PAI-1-mediated cell detachment while the inactive scrambled peptide had no effect. Thus, a direct interaction between occupied uPAR and integrins seems to be required for cell detachment by PAI-1.

Figure 4.

Cell detachment by PAI-1 and PN-1 requires the binding of uPAR to integrins. Mouse kidney epithelial cells expressing both human uPAR and either human wild-type α3-integrins (Panels A, E) or mutant (α3H245A) α3-integrins (Panels B, C, D, F) were allowed to attach to LN-5 (Panels A, B, E, F), VN (Panel C), or FN (Panel D) coated wells as described in the legend to Figure 1. After acid washing, the cells were incubated in RPMI/BSA with uPA alone, or with uPA followed by incubation with PAI-1 or PN-1 at 4°C and in the absence or presence of either peptide a325 or its inactive, scrambled form (sca325). In some experiments (Panels B, C, D) cells expressing mutant α3-integrin were also incubated in the presence of soluble uPAR (suPAR). After incubation, the wells were agitated vigorously, and the remaining attached cells were quantified. Statistical differences were measured by comparison with cells only incubated with uPA. In Panels C and D, cells incubated with uPA+inhibitor were also compared to cells exposed to inhibitor+suPAR. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

The importance of the uPAR/integrin interaction for cell detachment was also demonstrated in a second but very different experiment. In this experiment, we used a kidney epithelial cell line from α3-integrin-deficient mice that had been transfected with both human uPAR and a variant of human α3 integrin (α3H245A). This variant resembles the wild-type integrin in that it binds to LN-5; however, it cannot bind to uPAR. We hypothesized that because the matrix-engaged integrin (α3H245A) could not bind to uPAR, the cells would not be detached by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1, and this was indeed the case (Fig. 4B). We also predicted that if these same cells were attached to a matrix that does not engage α3 integrins (e.g., VN or FN which predominantly engage αV and α5 integrins, respectively), they would be detached by PAI-1, and this was also true (Fig. 4C, 4D). We showed previously that uPAR was essential for PAI-1-mediated cell detachment (Czekay et al, 2003). Thus, the observation that the efficiency of cell detachment by PAI-1 was enhanced by the addition of soluble uPAR (Fig. 4C, 4D) suggests that the cells produce low levels of endogenous uPAR and that it may be limiting in these experiments. Taken together, these observations suggest that PAI-1-induced cell detachment not only requires the presence of uPA:uPAR complexes on the cell surface, but also depends on the formation of complexes between integrins and the occupied uPAR. These data further suggest that uPAR mediates the de-adhesive activity of PAI-1 by preferentially binding to matrix-engaged integrins.

In parallel, we performed the experiments shown in panels 4C and 4D with PN-1 and in the presence of peptide a325. In these experiments (Panel 4E) cell detachment from LN-5 by PN-1 was blocked (Panel E), and cells expressing the mutant integrin did not respond to the presence of PN-1 (Panel 4F) suggesting that PN-1 induced cell detachment requires also interaction between uPAR and integrins.

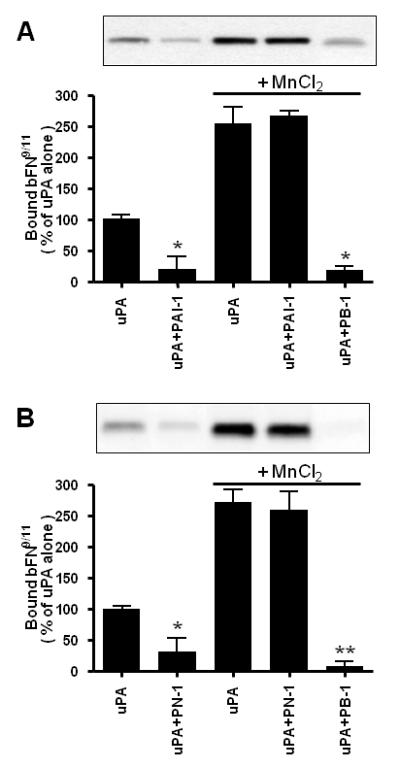

Sequential incubation with uPA and PN-1 can also lead to the inactivation of fibronectin-specific integrins

When HT-1080 cells were detached from VN by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1, they could not reattach to VN-coated wells or bind soluble VN (Czekay et al, 2003). Thus, VN-engaged integrins (i.e., αVβ3 and αVβ5) were inactivated by this treatment. Wei and coworkers (Wei et al, 2005) recently demonstrated that when these same cells were detached from FN by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1, they were unable to bind a biotinylated fragment of FN (i.e., bFN9/11). This fragment only binds to those α5β1 integrins which are in a high activity state for ligand binding (Ramos and DeSimone, 1996). Figure 5A shows that the sequential addition of uPA and PAI-1 led to a 75% decrease in the amount of bFN9/11 bound to HT1080 cells, thus confirming the above observations (Wei et al, 2005). This figure also shows that the presence of MnCl2 (known to activate integrins) increased the amounts of bFN9/11 bound to uPA treated as well as uPA plus PAI-1 treated cells to similar levels. Thus, while the level of active α5β1 integrins on the cell surface is dramatically reduced by treatment with uPA and PAI-1, there is no change in the total pool of these integrins. These results indicate that PAI-1 treatment leads to the reversible inactivation of these integrins. Finally, control experiments were performed to confirm that the binding of bFN9/11 to the surface of HT-1080 cells was mediated exclusively by the FN receptor, α5β1. In these experiments, uPA-treated cells were released by treatment with trypsin, and then were incubated with a specific α5β1-integrin-blocking mAb (i.e., PB-1). The presence of this mAb completely blocked the binding of bFN9/11 to the MnCl2 treated cells (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

α5β1 integrins are inactivated by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1 or PN-1. HT-1080 cells attached to FN-coated wells were acid washed and then incubated in RPMI/BSA in the absence or presence of uPA. The wells were washed to remove unbound uPA, and then incubated in the absence or presence of either PAI-1 (Panel A) or PN-1 (Panel B). Cells directly detached after incubation with uPA and either of the inhibitors were collected by centrifugation. Cells not treated with the inhibitors were detached by incubation with trypsin and also collected. All released cells were washed in RPMI/BSA and then incubated with biotinylated FN9/11 in the absence or presence of either MnCl2 or of a specific blocking monoclonal anti—α5β1 integrin antibody, PB-1. The boxed areas at the top of each panel are representative blots showing the amount of bound biotinylated FN9/11 as determined by SDS-PAGE and subsequent blotting with avidin-HRP followed by ECL, while the histograms show the quantitation of these results by densitometry from three experiments presented as mean ± S.D. Statistical differences were measured by comparison with cells exposed to uPA alone and in the presence or absence of MnCl2. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

Figure 5B shows that similar results are obtained when PN-1 was employed instead of PAI-1 (i.e., that when cells are attached to FN, the sequential addition of uPA and PN-1 leads to the inactivation of the FN-specific integrin, α5β1). Thus, these effects on the activity state of α5β1 are not specific for PAI-1. These observations, when considered together with our observation that VN-specific integrins are inactivated when cells are detached from VN (Czekay et al, 2003), suggest that treatment of cells with uPA inhibitors can lead to the inactivation of different pools of integrins. The specific class of integrins inactivated in this process seems to be determined by the composition of the underlying matrix.

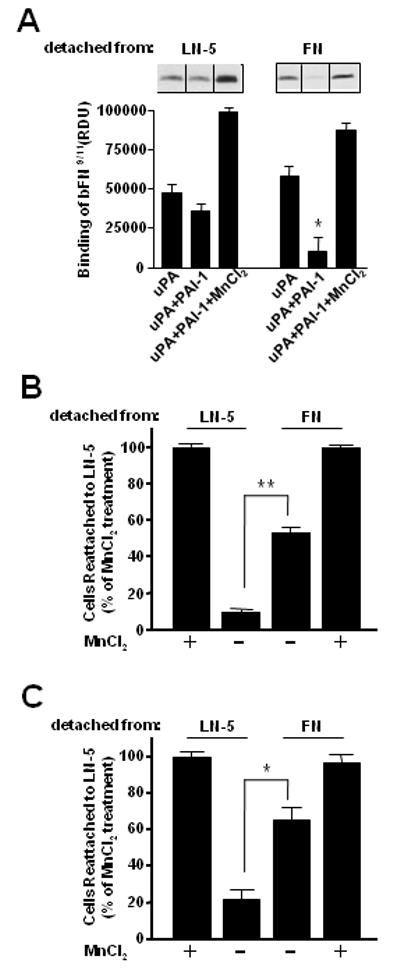

PAI-1 induced cell detachment specifically targets matrix-engaged integrins

Although cells express a variety of integrins, they adhere to their substratum through only a subset of these integrins (i.e., matrix-specific integrins). We designed experiments to test whether the uPA inhibitors target all classes only the matrix-engaged integrins or also cell surface integrins that are not actively engaged to the provided matrix.

To distinguish between these possibilities, HT-1080 cells were allowed to attach to LN-5 coated wells. The cells were then detached by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1 at 4°C (to prevent clearance and recycling of integrins), washed, and tested for their ability to bind the biotinylated FN fragment, bFN9/11. Figure 6A (left panels) shows that the cells detached by PAI-1 still bind approximately the same amount of bFN9/11 as the control cells (i.e., treated with uPA alone and then released by trypsin). Thus, the FN-specific integrins at the cell surface which did not engage the LN-5 matrix (e.g., α5β1), were not inactivated by the binding of PAI-1 to uPA. In contrast, when the cells were detached from a FN matrix by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1, they bound considerably less bFN9/11 than the control cells (Fig. 6A, right panels; see also Fig. 5). In the presence of MnCl2, the cells released from either LN-5 or FN showed similar binding capabilities for bFN9/11 suggesting comparable numbers of FN-specific integrins on the surface of cells detached from LN-5 vs. FN.

Figure 6.

Inhibitor-induced cell detachment specifically targets matrix-engaged integrins. HT-1080 cells attached to FN- or LN-5-coated wells were acid washed, and then incubated in RPMI/BSA with uPA alone or with uPA followed by incubation with PAI-1 at 4°C. In some experiments, the uPA-treated cells were detached by addition of trypsin. In all cases, the detached cells were collected by centrifugation, washed in RPMI/BSA, and either incubated with biotinylated FN9/11 (Panel A) or allowed to reattach to LN-5 coated microtiter plates at 4°C (Panel B). The amount of bound FN9/11 was then determined. Figure 6A shows a representative result from several experiments. The results shown in figures 6B and 6C are presented as the percentage of control cells that were detached from LN-5 by PAI-1 and PN-1, respectively, and then allowed to reattach to LN-5 in the absence or presence of MnCl2, and represent the mean ± S.D. Statistical differences were measured by comparison with cells exposed to uPA (Panel A), and between cells detached from LN-5 and FN (Panels B, C). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01. (RDU, relative density units).

In related experiments, cells were again detached from LN-5 or FN by sequential incubation with uPA and PAI-1, and then they were allowed to reattach to LN-5 coated microtiter plates. Figure 6B shows that the cells detached from LN-5 reattached poorly to LN-5 (∼10% of control cells) compared to the cells detached from FN (∼50% of control cells). Again, in the presence of MnCl2, the two populations of cells reattached to LN-5 to the same extent. We then repeated these experiments but used PN-1 to detach uPA-pretreated cells. The result was very similar in that cells detached from LN-5 reattached poorly to LN-5, whereas cells detached from FN reattached to LN-5 matrix in significantly higher numbers (Panel 6C).

Taken together, the above observations suggest that exposure of uPA-treated cells to uPA inhibitors (i.e., PAI-1, PN-1) seems to specifically initiate the inactivation of matrix-engaged integrins (e.g., α3β1 integrins for cells on LN-5 matrix, α5β1 integrins for cells on FN matrix). This observation helps to explain our previous observations that PAI-1 can detach cells from a variety of different ECM proteins.

DISCUSSION

Cell migration is a critical component of many normal and pathological processes, and regulated changes in the affinity state of adhesion receptors (e.g., integrins and uPAR) are essential for optimal cell motility (Lauffenburger and Horwitz 1996). It is becoming increasingly apparent that interactions between uPA and uPAR, and between uPAR and integrins, can influence the migratory behavior of cells (reviewed in (Ossowski and Aguirre-Ghiso, 2000)), and that this process is further modulated by PAIs. In this regard, PAI-1 can prevent the uPAR- and integrin-mediated adhesion of cells to VN by binding to the SMB domain (Deng et al, 1996;Stefansson and Lawrence, 1996;Kjoller et al, 1997;Deng et al, 2001;Palmieri et al, 2002), while stable transfection of some cells with PAI-1 or PAI-3 was reported to stimulate cell adhesion (Palmieri et al, 2002). The latter effect was dependent on the PAI activity of these molecules, and was associated with altered expression of some integrins by the transfected cells. Finally, by binding to the uPA present in uPA:uPAR:integrin complexes on the cell surface, PAI-1 can also detach cells (i.e., reverse integrin-mediated cell attachment) from VN and a variety of other ECM proteins (e.g., FN and type-1 collagen) (Czekay et al, 2003). This cell detachment process does not require the endocytic clearance of both uPAR and integrins by the endocytic receptor LRP, but can represent a novel mechanism that associates regulation cell adhesion with other cellular processes.

The goal of the current study was to further define the multi-step process by which PAI-1 is able to reverse integrin-mediated adhesion and initiate cell detachment. Initially we asked whether the cell detachment process was specific for PAI-1. PN-1 resembles PAI-1 in that it can bind to and inhibit uPA, and Figure 1A shows that PN-1 can also detach cells from VN. This process appears to be uPA-dependent since incubation of the cells with PN-1 alone (i.e., in the absence of uPA) had no effect. These observations raise the possibility that cell detachment can be initiated by any molecule that simply binds to and/or inactivates uPA. This hypothesis is clearly an oversimplification since the binding of antibodies to uPA on the cell surface, whether close to or distal from the active site, did not induce cell detachment (Fig. 1B). It also is evident that simply blocking (Fig. 1B) or specifically inhibiting (Fig. 1C) the active site in uPA, is also not sufficient to induce cell detachment. These observations suggest that it is the combination of the binding of specific macromolecular inhibitors (i.e., PAIs) to the active site in uPA, and the formation of covalent complexes between these inhibitors and the protease, that initiates the changes that ultimately lead to cell detachment. The binding of such PAIs to uPA present in uPA:uPAR:integrin complexes, may trigger specific conformational changes in this complex, and these changes may, in turn, decrease the strength of the interaction between the complex and the ECM. For example, it is likely that the binding of PAI-1 to uPA in the complex alters the conformation of the bound uPAR (Mondino et al, 1999). These changes in uPAR may then be transmitted to the associated integrins, lowering their affinity for their specific matrix ligand (this interaction is conformation-dependent (Xiong et al, 2003)), and initiating cell detachment. Although this hypothesis remains to be tested, it is supported by the observation that the binding of uPAR to α5β1 integrins alters their conformation (Wei et al, 2005). Whether PAI-1 and PN-1 binding to uPA:uPAR:integrin complexes initiate similar conformational changes still has to be determined.

The detachment of cells from VN by PAI-1 does not require but is associated with the internalization of uPAR and αV-integrins into EE (Czekay et al, 2001). Figure 2 shows that when uPA pretreated HT-1080 cells were incubated with PN-1, uPAR was again internalized into EE (Fig. 2, panel f). However, and in contrast to PAI-1 (Fig. 2, panel d), PN-1 did not induce the internalization of αVβ5 integrins (Fig. 2, panel g), even though it detached the cells (Fig. 1A). This difference between the effects of PAI-1 and PN-1 on integrin redistribution was not unique for αV integrins since PAI-1 induced the internalization of the LN-5-specific integrin, α3β1 (Fig. 2, panel e), but PN-1 did not (Fig. 2, panel h). Since both PAI-1 (Fig. 4A) and PN-1 (Fig. 4E) detached uPA pretreated cells from LN-5, these observations again suggest that cell detachment does not require the actual clearance of integrins from the cell surface. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that cell detachment by PAI-1 and PN-1 was still observed in the presence of reagents which inhibit (i.e., RAP, anti-LRP antibodies) or do not induce (i.e., PAI-1R76E) LRP mediated endocytosis of uPAR and integrins (Fig. 3).

We previously proposed that uPAR plays a central role in the PAI-1-mediated cell detachment process, and that it acts as a transmitter of the de-adhesive effects of PAI-1 toward integrins (Czekay et al, 2003). At the time, it was evident that the interaction between the occupied uPAR and cell surface integrins represented an important link between the inhibitor and the disengagement of integrins from the ECM. Our data (Fig. 4A) further emphasizes the importance of this interaction. When cells engaged a LN-5 matrix through α3β1 integrins, cell detachment by PAI-1 was completely blocked by a peptide (a325) which specifically inhibits the binding of uPAR to α3β1. An inactive, scrambled form of this peptide had no effect. The same results were recorded for PN-1. Cell detachment by PN-1 was completely blocked in the presence of a325 peptide (Fig. 4E). Together, these results suggest that the cell detachment process targets the matrix-engaged integrins (e.g., α3β1), and that direct binding of uPAR to those matrix-engaged integrins is essential for the subsequent detachment by PAI-1 and PN-1. The observation (Fig. 4B, 4F) that PAI-1 does not detach those cells expressing a mutant α3-integrin that cannot bind to uPAR (Zhang et al, 2003)), supports this conclusion.

The fact that cell detachment can be induced in the presence of inhibitors of LRP-dependent endocytosis (Fig. 3), suggests that cell detachment in this system results primarily from the inactivation of integrins and their disengagement from the matrix. Figure 5 confirms this hypothesis. For example, when uPA-pretreated HT-1080 cells were detached from FN by sequential incubation with either PAI-1 (Fig. 5A) or PN-1 (Fig. 5B), the detached cells showed a significantly reduced affinity for soluble FN (i.e., the ligand for active α5β1 integrins). Since these experiments were performed at 4°C to prevent integrin clearance, it is unlikely that the reduced binding resulted from depletion of the surface pool of α5β1 integrins. This conclusion is supported by the observation that reactivation of surface integrins by treatment with MnCl2 restored binding of soluble FN to these cells to same levels as to control cells. These results suggest that α5β1 integrins at the cell surface were reversibly inactivated by uPA/inhibitor treatment. These findings are very similar to previous results showing that αV-integrins (Czekay et al, 2003) and α5β1 integrins (Wei et al, 2005) show reduced activity in the presence of uPA and PAI-1.

PN-1, the second uPA inhibitor we tested, is as effective in detaching cells from various matrices as PAI-1, but we were unable to detect any integrin clearance during these PN-1 initiated events. Thus, we hypothesized that the underlying mechanism of cell detachment by these inhibitors seems to target the matrix-specific and matrix-engaged integrins for deactivation. If this is correct, then cells detached from one matrix by uPA/PAI-1 or uPA/PN-1 treatment should not be able to reattach to that same matrix, but would be able to attach to any other matrix as long as the cells express the required set of integrins. However, if uPA/inhibitor treatment should target all surface integrins for simultaneous inactivation to achieve cell detachment, then the detached cells should not reattach at all, despite the type of matrix protein they are exposed to afterwards. Our results shown in figure 6 seem to confirm the former option. Cells detached from LN-5 by uPA/PAI-1 treatment were unable to reattach to LN-5, but where able to bind FN. To the contrary, cells detached from FN by uPA/PAI-1 attached well to a LN-5 matrix but were unable to engage FN. Incubation with uPA/PN-1 produced the same results: cells detached from LN-5 attached to FN but did not reattach to LN-5, and vice versa. These results strongly support the hypothesis that uPA/inhibitor treatment leads to deactivation of matrix-specific/ matrix-engaged integrins. However, these processes do not necessarily require subsequent endocytic clearance of the receptors.

In summary, this report presents new insights into the mechanism of cell detachment by uPA inhibitors. It shows that this process is not unique to PAI-1 since PN-1, another uPA inhibitor, is also able to initiate uPA dependent cell detachment from several ECM proteins. We demonstrate that cell detachment requires the binding of the inhibitors to the active site in uPA, although inhibition of the active site per se is not sufficient. Finally, although integrins are rapidly endocytosed upon the addition of PAI-1, this mechanism of cell detachment by uPA inhibitors does not require an endocytic component since PN-1 initiates cell detachment but not endocytic clearance of integrins.

In this regard, it is important to note that the endocytic clearance of adhesion receptors and their subcellular redistribution could however play a role in other cellular processes where cell detachment is a necessary prerequisite (i.e. cell migration, cell invasion). Our studies, and those of others (Palmieri et al, 2002) taken together suggest that the binding of PAIs to uPA/uPAR/integrin complexes may enhance the attachment-detachment-reattachment cycle of integrins (Stefansson and Lawrence, 2003), thus contributing to and promoting cell motility. Such a model may provide an explanation as to why high levels of PAI-1 (Andreasen et al, 2000;Foekens et al, 2000) are strongly correlated with a poor prognosis in patients with certain cancers. Why PN-1 treatment leads to cell detachment, most likely through deactivation of integrins, but fails to initiate endocytic clearance of these receptors as we observed with PAI-1, is still an open question. Since conformational changes throughout the uAP/uPAR/integrin complex regulate to a certain degree the activity states for uPAR (i.e. uPA binding increases affinity of uPAR for VN and integrins) and perhaps for integrins as well, the binding of PN-1 or PAI-1 to these complexes might affect their interactions in different ways. It is possible that PN-1 binding to uPA/uPAR/integrin may induce changes in uPAR that lower its affinity for integrins resulting in separation of these receptors that is not observed upon incubation with PAI-1. Further studies beyond the scope of this paper are required to address this in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Scott Curriden for helpful discussions, and Marcia McRae for invaluable and outstanding assistance in preparing the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant HL31950 and is TSRI Manuscript No. 17383-CB.

This work was supported by NIH grant HL31950 and is TSRI Manuscript No. 17383-CB.

Abbreviations

- EE

early endosomes

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FN

fibronectin

- LN-5

laminin-5

- LRP

LDL receptor related protein

- PM

plasma membrane

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PN-1

protease nexin-1

- RAP

receptor associated protein

- SMB

somatomedin B

- uPA

urokinase type plasminogen activator

- uPAR

uPA receptor

- VN

vitronectin

Literature Cited

- Ghiso JA Aguirre, Kovalski K, Ossowski L. Tumor dormancy induced by downregulation of urokinase receptor in human carcinoma involves integrin and MAPK signaling. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:103. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Petersen HH. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:25–40. doi: 10.1007/s000180050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkenpas MB, Lawrence DA, Ginsburg D. Molecular evolution of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 functional stability. EMBO J. 1995;14:2969–2977. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman HA, Wei Y. Protease crosstalk with integrins: the urokinase receptor paradigm. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conese M, Blasi F. Urokinase/urokinase receptor system: internalization/degradation of urokinase-serpin complexes: mechanism and regulation. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1995;376:143–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubellis MV, Andreasen P, Ragno P, Mayer M, Dano K, Blasi F. Accessibility of receptor-bound urokinase to type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4828–4832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekay RP, Kuemmel TA, Orlando RA, Farquhar MG. Direct binding of occupied urokinase receptor (uPAR) to LDL receptor-related protein is required for endocytosis of uPAR and regulation of cell surface urokinase activity. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1467–1479. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekay R-P, Aertgeerts K, Curriden SA, Loskutoff DJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 detaches cells from extracellular matrices by inactivating integrins. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:781–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekay R-P, Loskutoff DJ. Unexpected role of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 in cell adhesion and detachment. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:1090–1096. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng G, Curriden SA, Hu G, Czekay R-P, Loskutoff DJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 regulates cell adhesion by binding to the somatomedin B domain of vitronectin. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:23–33. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng G, Curriden SA, Wang S, Rosenberg S, Loskutoff DJ. Is plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 the molecular switch that governs urokinase receptor-mediated cell adhesion and release? J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1563–1571. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foekens JA, Peters HA, Look MP, Portengen H, Schmitt M, Kramer MD, Brunner N, Janicke F, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Henzen-Logmans SC, van Putten WL, Klijn JG. The urokinase system of plasminogen activation and prognosis in 2780 breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60:636–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfinger LE, Stack MS, Jones JC. Processing of laminin-5 and its functional consequences: role of plasmin and tissue-type plasminogen activator. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:255–265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heegaard CW, Simonsen ACW, Oka K, Kjoller L, Christensen A, Madsen B, Ellgaard L, Chan L, Andreasen PA. Very low density lipoprotein receptor binds and mediates endocytosis of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-type- 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor complex. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20855–20861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz J, Goldstein JL, Strickland DK, Ho YK, Brown MS. 39-kDa protein modulates binding of ligands to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein/alpha 2-macroglobulin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21232–21238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikubo Y, Okumura Y, Loskutoff DJ. Identification of the disulfide bonds in the recombinant somatomedin B domain of human vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27109–27119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjoller L. The urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell motility. Biol Chem. 2002;383:5–19. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjoller L, Kanse SM, Kirkegaard T, Rodenburg KW, Ronne E, Goodman SL, Preissner KT, Ossowski L, Andreasen PA. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 represses integrin- and vitronectin-mediated cell migration independently of its function as an inhibitor of plasminogen activation. Exp Cell Res. 1997;232:420–429. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Gotoh J, Shinohara H, Moniwa N, Terao T. Inhibition of the metastasis of Lewis lung carcinoma by antibody against urokinase-type plasminogen activator in the experimental and spontaneous metastasis model. Thromb Haemost. 1994;71:474–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laura R, Robison DJ, Bing DH. p-Amidinophenyl)methanesulfonyl fluoride, an irreversible inhibitor of serine proteases. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4859–4864. doi: 10.1021/bi00562a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondino A, Resnati M, Blasi F. Structure and function of the urokinase receptor. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82(Suppl 1):19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DH, Catling AD, Webb DJ, Sankovic M, Walker LA, Somlyo AV, Weber MJ, Gonias SL. Myosin light chain kinase functions downstream of Ras/ERK to promote migration of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-stimulated cells in an integrin-selective manner. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:149–164. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DH, Webb DJ, Catling AD, Song Q, Dhakephalkar A, Weber MJ, Ravichandran KS, Gonias SL. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator stimulates the Ras/Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway and MCF-7 cell migration by a mechanism that requires focal adhesion kinase, Src, and Shc. Rapid dissociation of GRB2/Sps-Shc complex is associated with the transient phosphorylation of ERK in urokinase-treated cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19382–19388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909575199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjær A, Conese M, Christensen EI, Olson D, Cremona O, Gliemann J, Blasi F. Recycling of the urokinase receptor upon internalization of the uPA:serpin complexes. EMBO J. 1997;16:2610–2620. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura Y, Kamikubo Y, Curriden SA, Wang J, Kiwada T, Futaki S, Kitagawa K, Loskutoff DJ. Kinetic analysis of the interaction between vitronectin and the urokinase receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9395–9404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski L, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Urokinase receptor and integrin partnership: coordination of signaling for cell adhesion, migration and growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:613–620. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri D, Lee JW, Juliano RL, Church FC. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and -3 increase cell adhesion and motility of MDA-MB-435 Breast Cancer Cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40950–40957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powelka AM, Sun J, Li J, Gao M, Shaw LM, Sonnenberg A, Hsu VW. Stimulation-dependent recycling of integrin beta1 regulated by ARF6 and Rab11. Traffic. 2004;5:20–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager GW, Breuss JM, Steurer S, Olcaydu D, Mihaly J, Brunner PM, Stockinger H, Binder BR. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2-induced initial endothelial cell migration depends on the presence of the urokinase receptor. Circ Res. 2004;94:1562–1570. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000131498.36194.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos JW, DeSimone DW. Xenopus embryonic cell adhesion to fibronectin: position-specific activation of RGD/synergy site-dependent migratory behavior at gastrulation. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:227–240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffert D, Ciambrone G, Wagner NV, Binder BB, Loskutoff DJ. The somatomedin B domain of vitronectin: Structural requirements for the binding and stabilization of active type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2659–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson S, Lawrence DA. Old dogs and new tricks, proteases, inhibitors, and cell migration. Science’s stke4. 2003 doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.189.pe24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson S, Lawrence DA. The serpin PAI-1 inhibits cell migration by blocking integrin αvβ3 binding to vitronectin. Nature. 1996;383:441–443. doi: 10.1038/383441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson S, Muhammad S, Cheng X-F, Battey FD, Strickland DK, Lawrence DA. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 contains a cryptic high affinity binding site for the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6358–6366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Kerins DM, Hao Q, Inagami T, Vaughan DE. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor mediates tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18268–18272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarui T, Mazar AP, Cines DB, Takada Y. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (CD87) is a ligand for integrins and mediates cell-cell interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3983–3990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz DA, Natkin LR, Fujita RM, Wei Y, Chapman HA. Plasmin and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 promote cellular motility by regulating the interaction between the urokinase receptor and vitronectin. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:58–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI119521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liang X, Wu S, Murrell GA, Doe WF. Inhibition of colon cancer metastasis by a 3’- end antisense urokinase receptor mRNA in a nude mouse model. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:257–262. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200102)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1178>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Czekay R-P, Robillard L, Kugler MC, Zhang F, Kim KK, Xiong JP, Humphries MJ, Chapman HA. Regulation of α5β1 integrin conformation and function by urokinase receptor binding. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:501–511. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Eble JA, Wang Z, Kreidberg JA, Chapman HA. Urokinase receptors promote β1 integrin function through interactions with integrin α3β1. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2975–2986. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Waltz DA, Rao N, Drummond RJ, Rosenberg S, Chapman HA. Identification of the urokinase receptor as an adhesion receptor for vitronectin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32380–32388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods AJ, White DP, Caswell PT, Norman JC. PKD1/PKCmicro promotes alphavbeta3 integrin recycling and delivery to nascent focal adhesions. EMBO J. 2004;23:2531–2543. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Integrins, cations and ligands: making the connection. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1642–1654. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Mizukami I, Todd RF, III, Petty HR. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptors associate with beta1 and beta3 integrins of fibrosarcoma cells: dependence on extracellular matrix components. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1682–1689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatohgo T, Izumi M, Kashiwagi H, Hayashi M. Novel purification of vitronectin from human plasma by heparin affinity chromatography. Cell Struct Funct. 1988;13:281–292. doi: 10.1247/csf.13.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yebra M, Goretzki L, Pfeifer M, Mueller BM. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator binding to its receptor stimulates tumor cell migration by enhancing integrin-mediated signal transduction. Exp Cell Res. 1999;250:231–240. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Tom CC, Kugler MC, Ching TT, Kreidberg JA, Wei Y, Chapman HA. Distinct ligand binding sites in integrin alpha3beta1 regulate matrix adhesion and cell-cell contact. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:177–188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]