Abstract

Fli-1 and Erg are closely related members of the Ets family of transcription factors. Both genes are translocated in human cancers, including Ewing's sarcoma, leukemia, and in the case of Erg, more than half of all prostate cancers. Although evidence from mice and humans suggests that Fli-1 is required for megakaryopoiesis, and that Erg is required for normal adult hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) regulation, their precise physiological roles remain to be defined. To elucidate the relationship between Fli-1 and Erg in hematopoiesis, we conducted an analysis of mice carrying mutations in both genes. Our results demonstrate that there is a profound genetic interaction between Fli-1 and Erg. Double heterozygotes displayed phenotypes more dramatic than single heterozygotes: severe thrombocytopenia, with a significant deficit in megakaryocyte numbers and evidence of megakaryocyte dysmorphogenesis, and loss of HSCs accompanied by a reduction in the number of committed hematopoietic progenitor cells. These results illustrate an indispensable requirement for both Fli-1 and Erg in normal HSC and megakaryocyte homeostasis, and suggest these transcription factors may coregulate common target genes.

The E-twenty-six specific (Ets) proteins are a family of more than 20 helix–loop–helix domain transcription factors that have been implicated in a myriad of cellular processes (1). Fli-1 and Erg are Ets proteins that share greater homology to each other than to other Ets family members. Fli-1 is mutated in a number of cancers, including Ewing's sarcoma and erythroleukemia (2, 3). Genetic manipulation in mice (4, 5) and mutations in humans (4, 6) have revealed multiple roles for Fli-1 in hematopoiesis including the production of megakaryocytes and platelets. Fli-1 is also implicated in the regulation of important stem cell genes, suggesting a role within the hematopoietic stem cell compartment (7, 8). Erg is also a proto-oncogene, translocated in Ewing sarcoma, leukemia, and prostate cancer (9–11). We recently reported a mouse model of Erg dysfunction, ErgMld2, in which an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced point mutation causes profound loss of Erg function. These mice revealed an indispensable requirement for Erg in definitive hematopoiesis with ErgMld2/Mld2 embryos dying at midgestation. Analyses of Erg+/Mld2 adult mice revealed that Erg is required for normal adult HSC homeostasis. HSCs are reduced in number in Erg+/Mld2 mice and unable to compete effectively with Erg+/+ cells to reconstitute irradiated transplant recipients (12).

In translocations driving Ewing's sarcoma, Fli-1 and Erg appear to be interchangeable; either Fli-1 or Erg can fuse with the gene encoding an RNA binding protein, EWS, and give rise to clinically indistinguishable disease (13). Moreover, in vitro data suggests that Fli-1 and Erg may heterodimerize to regulate sets of overlapping target genes (14, 15), raising the prospect that these proteins may, in part, be redundant. To explore the relationship between Fli-1 and Erg in a physiological setting, we analyzed mice heterozygous for mutations in both genes. We observed a profound genetic interaction between Fli-1 and Erg in hematopoiesis, with a specific requirement for both genes evident in the regulation of HSC number and function, and in the development of the megakaryocyte lineage.

Results

A Genetic Interaction Between Fli-1 and Erg.

To examine the relationship between Erg and Fli-1 at the genetic level, we crossed mice heterozygous for a targeted deletion of the Fli-1 C-terminal activation domain (5) with mice heterozygous for the ErgMld2 allele, which encodes a point mutation in the DNA-binding Ets domain of Erg. At weaning, Fli-1+/− Erg+/+ (hereafter referred to as Fli-1+/−) and Fli-1+/+ Erg+/Mld2 (hereafter referred to as Erg+/Mld2) mice were observed at the expected Mendelian ratios, however, only half the expected number of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice were present (observed/expected ratios were: Fli-1+/+ Erg +/+ 1.2:1, Fli-1+/− 1.1:1, Erg+/Mld2 1.1:1, and Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 0.6:1). Mice of all genotypes appeared outwardly healthy, and a histopathological survey of tissues in 8-week-old mice showed no gross abnormalities in the thymus, spleen, pancreas, lymph nodes, liver, kidney, bladder, small bowel, skin, or salivary gland. We then examined peripheral blood at 8 to 10 weeks of age. As described, Erg+/Mld2 mice exhibit a mild thrombocytopenia (12) (Table 1). The peripheral blood counts of Fli-1+/− mice were normal. In contrast, Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice exhibited severe thrombocytopenia (platelet counts ≈25% that observed in Erg+/Mld2 mice) and pancytopenia with deficits of 10–50% in red blood cells and white blood cells including lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes and eosinophils (Table 1 and Fig. 1A).

Table 1.

Peripheral blood counts

| Fli-1+/+Erg+/+n = 16 | Fli-1+/−n = 16 | Erg+/Mld2n = 16 | Fli-1+/−Erg+/Mld2n = 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets (× 106/mL) | 1146 ± 162 | 986 ± 163 | 898 ± 138† | 202 ± 130* |

| Erythrocytes (× 109/mL) | 9.8 ± 0.9 | 10.6 ± 0.5ϕ | 10.4 ± 1.1 | 8.7 ± 0.7* |

| Hematocrit, % | 47.8 ± 5.5 | 52.4 ± 2.3ϕ | 50.7 ± 5.3 | 44.1 ± 4.6* |

| Leukocytes (× 106/mL) | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 1.9 | 2.9 ± 1.4* |

| Neutrophils (× 106/mL) | 0.78 ± 0.45 | 0.46 ± 0.20 | 0.60 ± 0.43 | 0.21 ± 0.14* |

| Lymphocytes (× 106/mL) | 4.4 ± 2.2 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.3* |

| Monocytes (× 106/mL) | 0.37 ± 0.59 | 0.21 ± 0.27 | 0.16 ± 0.14 | 0.07 ± 0.12 |

| Eosinophils (× 106/mL) | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.01* |

Peripheral blood counts from 8- to 10-week-old mice. Data represent mean ± SD.

P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ with that of Fli-1+/− mice.

P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Fli-1+/+Erg+/+ with that of Erg+/Mld2 mice.

P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Erg+/Mld2 with that of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

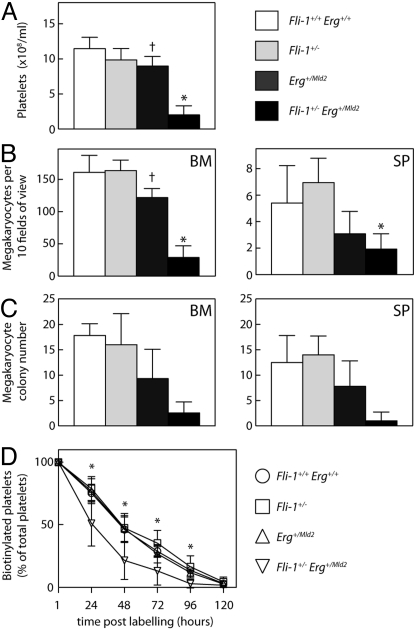

Fig. 1.

Decreased megakaryopoiesis in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice. (A) Peripheral blood platelet counts from 8- to 10-week-old mice demonstrate mild thrombocytopenia in Erg+/Mld2 mice and severe thrombocytopenia in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice (n = 16 mice per genotype). (B) Number of megakaryocytes in histological sections of bone marrow (BM) and spleen (SP) per 10 high powered fields of view (×200) (n = 4–7 mice per genotype). (C) Number of megakaryocyte colonies from 2.5 × 104 nucleated bone marrow (BM) or 1.0 × 105 nucleated spleen (SP) cells cultured with stem cell factor, IL-3, and erythropoietin [n = 6–7 mice per genotype (BM) or 4–5 mice per genotype (SP)]. (D) Peripheral blood samples were taken from mice 1, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h after injection of biotin (n = 10–12 mice per genotype). Data represent mean ± SD. †, P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ with that of Erg+/Mld2 mice. *, P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Erg+/Mld2 with that of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice.

Fli-1 and Erg Are Required for Normal Megakaryopoiesis.

To establish whether a defect in platelet production was responsible for the observed thrombocytopenia, we examined megakaryopoiesis. Normal numbers of megakaryocytes were observed in the bone marrow of Fli-1+/− mice. Compared with wild-type controls, the bone marrow of Erg+/Mld2 mice demonstrated a modest but significant reduction in the number of megakaryocytes, consistent with their mild thrombocytopenia. In contrast, the number of megakaryocytes in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 bone marrow was <25% that seen in Erg+/Mld2 mice and a similar trend was also observed in the spleen (Fig. 1B). The number of megakaryocyte progenitor cells in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 bone marrow and spleen was reduced to a greater extent than that of megakaryocytes. A more modest reduction in megakaryocyte progenitor cells was evident in the tissues of Erg+/Mld2 mice, as described in ref. 12. In Fli-1+/− mice, the numbers of these cells was normal (Fig. 1C and Table 2). Normal levels of TPO were detected in the serum of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice, suggesting that a deficit in production of the major cytokine regulator of steady-state megakaryopoiesis could not account for the defective megakaryopoiesis observed in these mice.

Table 2.

Myeloid progenitor cell numbers.

| Colony Number | Genotype |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fli-1+/+Erg+/+ | Fli-1+/− | Erg+/Mld2 | Fli-1+/−Erg+/Mld2 | |

| Bone marrow (per 25,000 cells) | ||||

| Blast | 12 ± 2 | 12 ± 3 | 6 ± 2† | 1 ± 1* |

| Granulocyte | 12 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | 8 ± 2 | 3 ± 2* |

| Mixed granulocyte/macrophage | 15 ± 3 | 17 ± 6 | 9 ± 5 | 3 ± 3 |

| Macrophage | 15 ± 4 | 10 ± 2 | 6 ± 3† | 3 ± 2 |

| Eosinophil | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

| Megakaryocyte | 18 ± 2 | 16 ± 6 | 9 ± 6 | 3 ± 2 |

| Total | 72 ± 11 | 67 ± 15 | 39 ± 17† | 13 ± 7* |

| Spleen (per 100,000 cells) | ||||

| Blast | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0.2 ± 0.4 |

| Granulocyte | 1 ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed granulocyte/macrophage | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Macrophage | 2 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Eosinophil | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Megakaryocyte | 13 ± 5 | 14 ± 4 | 8 ± 5 | 1 ± 2 |

| Total | 18 ± 6 | 19 ± 3 | 9 ± 4† | 1 ± 2* |

Cells from 8- to 10-week-old mice were cultured for 7 d with stem cell factor, IL-3 and erythropoietin. n = 6–7 mice per genotype for bone marrow cultures and 4–5 mice per genotype for spleen cultures. Data represent mean ± SD.

P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ with that of Erg+/Mld2 mice.

P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Erg+/Mld2 with that of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Increased Platelet Clearance in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 Mice.

Because thrombocytopenia can be caused by changes in platelet life span and/or clearance, we examined these parameters by labeling platelets and tracking their survival in vivo. Absolute platelet life span—defined as the time for which we could detect the presence of labeled platelets in the circulation—was unchanged in Fli-1+/− and Erg+/Mld2 mice (Fig. 1D). In Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 animals, a small but statistically significant reduction in platelet life span was observed. Furthermore, an increase in the rate of platelet clearance—indicated by the shape of the curve—was evident (Fig. 1D). To determine whether these changes were due to factors intrinsic to platelets or the environment in which they circulated, we performed adoptive transfers of wild-type or Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 platelets into wild-type recipients. No significant difference in platelet life span or platelet clearance was observed [see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A]. We then performed the reciprocal experiment, and found that upon transfer into Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 recipients, wild-type platelets were cleared more quickly than when transferred into wild-type recipients (Fig. S1B). The kinetics of platelet clearance closely resembled that seen in unmanipulated Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice. Taken together, these data suggest that although defective megakaryocyte production is the dominant factor, a mildly increased platelet clearance rate in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice due to changes extrinsic to platelets, may contribute to the observed thrombocytopenia.

Ultrastructural Abnormalities in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 Megakaryocytes.

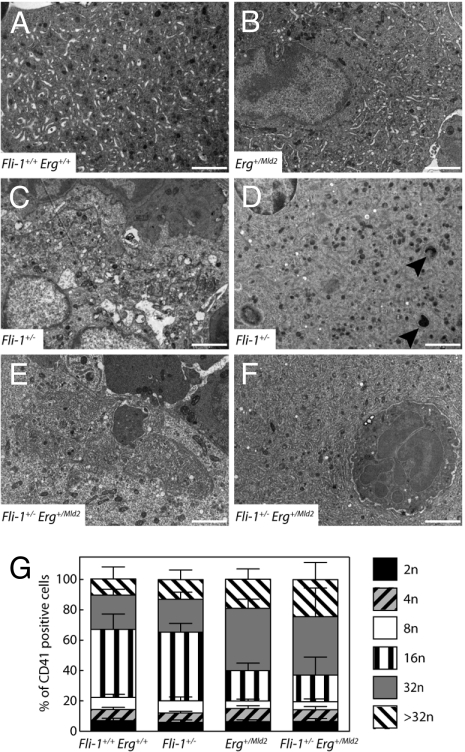

Fetal liver derived Fli-1−/− megakaryocytes were reported to exhibit ultrastructural defects (4) similar to those found in bone marrow megakaryocytes from Paris Trousseau Syndrome (PTS) patients (16), the latter characterized by hemizygous deletion of a region of chromosome 11 that contains Fli-1. We used transmission electron microscopy to explore the relative contribution of Fli-1 and Erg to megakaryocyte morphology. Consistent with previous observations, Fli-1+/− bone marrow megakaryocytes displayed a disorganized demarcation membrane system (DMS), vacuolization and examples of fused α granules similar to that reported in PTS patients (Fig. 2 C and D). In contrast, no obvious ultrastructural defects were observed in Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes (Fig. 2B). Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes however, demonstrated striking abnormalities. The DMS was distributed unevenly in some cells and in those with abundant DMS, it rarely formed platelet territories (Fig. 2 E and F). Emperipolesis (the transit of smaller cells through megakaryocytes) was also observed at a very high frequency: 0/19 of megakaryocytes in wild-type bone marrow compared with 3/27 in Fli-1+/− 2/14 in Erg+/Mld2, and 7/17 in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 marrow (Fig. 2 E and F). Megakaryocytes showing signs of apoptosis or necrosis were not observed in mice of any genotype. Whereas the DNA ploidy profiles of Fli-1+/− megakaryocytes were indistinguishable from wild-type, with the majority of megakaryocytes observed in the 16N ploidy class, both Erg+/Mld2 and Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice exhibited a modal megakaryocyte ploidy of 32N (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice exhibit abnormal megakaryocyte maturation. Electron micrographs of megakaryocytes from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ (A) and Erg+/Mld2 (B) bone marrow revealed normal morphology with a mature cytoplasm containing numerous granules and well ordered DMS. A proportion of Fli-1+/− megakaryocytes contained large vacuoles and a disorganized DMS (C) and others contained giant granules, indicated by arrowheads (D). Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes exhibited a disorganized DMS (E and F) and a high frequency of emperipolesis (F). (Original magnification 10,000×; Scale bar, 2 μm). (G) Megakaryocyte ploidy distribution profiles of CD41+ bone marrow cells are normal in Fli-1+/− mice but altered in Erg+/Mld2 and Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice (n = 13–15 mice per genotype).

Fli-1 and Erg Are Required for Adult HSC Homeostasis.

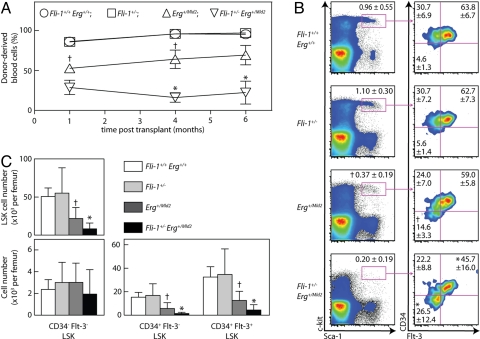

The deficiency in megakaryocyte colony forming cells (CFC) in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice was accompanied by reduced numbers of blast cell colony forming cells and progenitor cells of all myeloid lineages (Table 2). This reduction was significantly greater than the approximate 50% deficiency observed in Erg+/Mld2 mice (12) (Table 2). As observed for other myeloid and megakaryocyte progenitors, analysis of erythroid progenitor cell numbers by methylcellulose culture of bone marrow and spleen cells demonstrated low numbers of blast forming unit–erythroid (BFU-E) in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice, particularly in the spleen. (Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ 19 ± 4 BFU-E per 104 bone marrow cells and 9 ± 4 BFU-E per 105 spleen cells, Fli-1+/− 24 ± 2 and 20 ± 5, Erg+/Mld2 13 ± 2 and 6 ± 1, Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 7 ± 4 and 1 ± 0, n = 2–4 mice per genotype). In Erg+/Mld2 mice, reduced progenitor cell number was associated with reduced stem cell function (12). To explore HSC function in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice, we performed transplantation experiments, in which unfractionated bone marrow was injected into irradiated wild-type recipients. Bone marrow from Erg+/Mld2 mice, as reported in ref. 12, exhibited a reduced capacity to contribute to hematopoiesis over several months in transplant recipients, whereas bone marrow from Fli-1+/− mice had wild-type activity (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, the ability of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 marrow to reconstitute irradiated recipients was profoundly impaired, with activity approximately 30% that of Erg+/Mld2 donors (Fig. 3A). Enumeration of Lin−, Sca-1+, c-Kit+ cells (LSK), which are enriched for early hematopoietic progenitor cells, revealed that in contrast to Erg+/Mld2 mice, which exhibit a decrease in LSK cells, both as a proportion of the bone marrow and absolute number, Fli-1+/− mice had normal numbers of LSK cells (Fig. 3 B and C). However, when the Fli-1 and Erg mutations were combined, we observed a significant reduction in the absolute number of LSK cells to just 16% of wild-type and ≈40% of Erg+/Mld2 numbers (Fig. 3 B and C).

Fig. 3.

Fli-1 and Erg are required for adult HSC homeostasis. (A) Percent nucleated peripheral blood cells derived from donor bone marrow in myeloablated Ly51/2 recipient mice injected with 2 × 106 unfractionated bone marrow cells from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ (circles), Fli-1+/− (squares), Erg+/Mld2 (upright triangle), or Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 (inverted triangle) mice (n = 4 donors per genotype; and 3 recipients per donor, assessed 1, 4, and 6 months after transplantation). (B) Flow cytometry of viable, lineage-negative cells (Left) and LSK cells (Right) in unfractionated bone marrow from mice of the genotype indicated. The gate used to identify the LSK populations is outlined. A representative plot is shown with numbers in quadrants indicating percent events in each gated area (mean ± SD; n = 11–12 mice per genotype). Fewer events are presented for Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice as a result of reduced LSK number. (C) Absolute numbers of Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+, Fli-1+/−, Erg+/Mld2 or Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 LSK cells (Upper), and CD34– Flt3– LSK cells (LT-HSCs) (Lower Left), CD34+ Flt3– LSK cells (ST-HSCs), and CD34+ Flt3+ LSK cells (MPPs) (Lower Right) per mouse femur (mean ± SD; n = 11–12 mice per genotype). †, P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+ with that of Erg+/Mld2 mice. *, P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Erg+/Mld2 with that of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice.

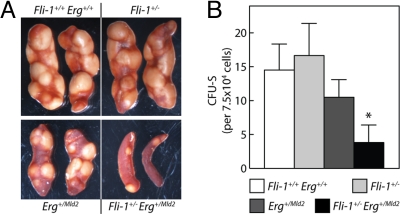

To further dissect the LSK defect, we examined bone marrow populations enriched in long-term repopulating HSCs (LT-HSC) (CD34− Flt3− LSK), short-term repopulating HSCs (ST-HSC) (CD34+ Flt3− LSK), and multipotent progenitor cells (MPP) (CD34+ Flt3+ LSK) (17). No alterations in the distribution or absolute numbers of LSK subsets were evident in Fli-1+/− bone marrow; however, in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice we observed an exacerbation of the reduction in the absolute number of ST-HSC and MPP apparent in Erg+/Mld2 mice (Fig. 3C). Consistent with a functional defect within multipotent progenitor cells, bone marrow from Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice contained fewer colony forming unit-spleen cells (CFU-S) than Erg+/Mld2 mice. In addition, the colonies produced by Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 donor bone marrow appeared smaller (Fig. 4). There was no reduction in the size or number of colonies formed by Fli-1+/− bone marrow.

Fig. 4.

Reduced CFU-S in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice. (A) Representative examples of macroscopic spleen colonies (CFU-S) from wild-type irradiated recipients injected with 7.5 × 104 unfractionated bone marrow cells from Fli-1+/+ Erg+/+, Fli-1+/−, Erg+/Mld2, or Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice as indicated. (B) Colonies were counted 11 days after transplantation. Data represent mean ± SD; n = 3–5 donors, 3 recipients per donor. *, P < 0.05 for comparison of data from Erg+/Mld2 with that of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice.

Discussion

The phenotypes of mice homozygous for mutations in Fli-1 or Erg suggest distinct roles for these factors in embryonic development. Although both genes are essential for life beyond midgestation, Fli-1−/− mice succumb to the effects of defective angiogenesis (4, 5, 12) whereas mice homozygous for a loss of function Erg allele show little sign of vascular defects, but a failure of definitive hematopoiesis (12). Mice heterozygous for these alleles survive to adulthood; defects in hematopoiesis have not been reported for Fli-1+/− mice, but Erg+/Mld2 animals have significant hematopoietic stem cell defects and mild deficiencies in specific mature lineages (4, 5, 12). To explore the genetic interaction between Fli-1 and Erg in the regulation of hematopoiesis, we compared the phenotypes of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 double heterozygotes with those of Fli-1+/− or Erg+/Mld2 mice. Our analyses have identified distinct and overlapping actions of these related Ets family transcription factors.

In the blood, the most obvious effect of heterozygosity of both Fli-1 and Erg mutations was severe thrombocytopenia. Some component of the reduction in platelet count can probably be ascribed to a modest increase in platelet clearance rate; however, the major factor is a dramatic reduction in megakaryopoiesis. We observed profound reductions in the number of megakaryocytes and their committed progenitor cells in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mice. Platelet numbers are clearly sensitive to Erg gene dosage, with mild thrombocytopenia observed in Erg+/Mld2 mice (12). Our analyses of Fli-1+/− animals revealed no anomaly in megakaryocyte or platelet numbers. Increased numbers of megakaryocyte progenitor cells were reported in 1 study of Fli-1−/− fetal liver (4); however, an independent study reported a reduction in the number of Fli-1−/− fetal liver CFU-mix (5) and cultured Fli-1−/− aorta-gonad-mesonephros region (AGM) produced fewer megakaryocytes than wild-type AGM (18), consistent with a potential deficit of committed megakaryocyte progenitors (5). Our data are consistent with regulation of megakaryocyte progenitor cell number by Fli-1 in concert with Erg.

Ultrastructural abnormalities similar to those observed in bone marrow megakaryocytes of PTS patients with hemizygous deletion of 11q (where Fli-1 is located), have been reported in Fli-1−/− fetal liver derived megakaryocytes (4). Our observation that a heterozygous mutation of Fli-1 is sufficient to replicate these abnormalities in bone marrow megakaryocytes supports an essential role for Fli-1 in the morphological differentiation of these cells. The observed defects in cytoplasmic maturation suggest Fli-1 regulates the later aspects of megakaryocyte maturation, consistent with increasing levels of Fli-1 expression throughout megakaryocyte development (19). Whereas no morphological abnormalities were observed in Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes, the defects in cells from the double heterozygotes were more severe than in Fli-1+/− cells. These data suggest that both Fli-1 and Erg are required for the production of megakaryocytes and their correct morphological differentiation.

Excessive emperipolesis was observed in both Fli-1+/− and Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes and this phenotype was exacerbated in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes, suggesting that Erg may also contribute to DMS maturation, as megakaryocyte emperipolesis has been reported in humans and mice with DMS-related pathologies (20). However, because emperipolesis is also a means for hematopoietic cells to transit from bone marrow to the blood stream and is known to occur more frequently in mice subjected to hematopoietic stresses (20), the increased frequency of emperipolesis observed in Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 megakaryocytes may be an indirect reflection of compromised hematopoiesis in these mice.

Previous data have established that Erg is required for normal HSC homeostasis (12). In addition to an ≈50% reduction in the absolute number of bone marrow LSK cells, Erg+/Mld2 HSCs are out-competed by their wild-type counterparts in transplantation assays (12). Fli-1, along with Scl and Gata2, has been proposed to play a role in the specification of HSCs in the embryo (7, 8); however, in adult Fli-1+/− mice, we observed no changes in LSK number, nor in the capacity of HSCs to reconstitute hematopoiesis. In contrast, in mice with mutations in both Fli-1 and Erg, HSC defects were more severe than in Erg+/Mld2 animals. We observed a profound defect in the ability of Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 bone marrow to reconstitute irradiated recipients, which was at least partially attributable to a reduction in the numbers of cells within the LSK population, in particular ST-HSCs and MPPs. In addition, CFU-S assays revealed decreased colony size indicative of a functional defect within multipotent progenitor cells. Thus, our data demonstrate that Fli-1, via a genetic interaction with Erg, is also critical for normal HSC number and function.

Our results establish that Erg and Fli-1 have overlapping functions in hematopoiesis, in particular in the regulation of megakaryopoiesis and HSC homeostasis. Although it is possible that they do so via distinct genetic pathways, published data suggest Fli-1 and Erg might regulate common target genes. Fli-1 and Erg have highly homologous DNA binding (Ets) domains, which recognize an identical Ets binding site (EBS) and in ChIP studies and reporter assays in cell lines, both are able to bind and transactivate promoters/enhancers of genes encoding the Ig heavy chain and endoglin, although it is not known whether binding of Fli-1 and Erg to regulator elements occurs simultaneously (15, 21, 22). Although current evidence suggests that Ets proteins bind DNA as monomers, the ability of Fli-1 and Erg to heterodimerize may serve as a mechanism to simultaneously target Erg and Fli-1 to distinct EBSs within the same region of common target genes, many of which have multiple EBSs. In cell line studies, Fli-1 has been shown to bind a transcriptional enhancer element in the Scl gene (8), a master regulator of hematopoietic specification, and analysis of fetal hematopoiesis suggests that Scl and Fli-1 may participate in a genetic network important in hematopoietic development (7). Microarray analysis of Erg+/Mld2 LSK cells suggests that Erg target genes relevant for HSC regulation may include genes not previously associated with HSC function, such as Mmp2 and Igfr2 (12). Future studies comparing the transcriptional profiles of hematopoietic cells from double Fli-1+/− Erg+/Mld2 mutants with this existing data will further refine the list of candidate Fli-1/Erg target genes in hematopoietic regulation, allowing a focused functional dissection of physiologically regulated targets.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Erg+/Mld2 mice (12) and Fli-1+/− mice (5) have been described previously. All animal experiments were approved by the Melbourne Health Research Directorate Animal Ethics Committee or Walter and Eliza Hall Institute Animal Ethics Committee.

Hematology.

Automated cell counts were performed on blood collected from the retroorbital plexus into Microtainer tubes containing EDTA (Becton Dickinson and Company) using an Advia 2120 analyser (Siemens). Megakaryocytes were enumerated in sections of sternum and spleen stained with hematoxylin and eosin with a minimum of 10 high power fields (200×) analyzed. Hematopoietic cells were clonally cultured as described in ref. 23. Briefly, cultures of 2.5 × 104 nucleated adult bone marrow cells or 105 adult spleen cells in 1 mL of 0.3% (wt/vol) agar in DMEM supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) newborn calf serum were stimulated with mouse stem cell factor (100 ng/mL), mouse interleukin (IL)-3 (10 ng/mL), and human erythropoietin (4 units/mL). Alternatively 104 nucleated adult bone marrow cells or 105 adult spleen cells were cultured in 1 mL MethoCult with cytokines (Stemcell Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cultures were incubated for 7 d at 37 °C in a fully humidified atmosphere of 10% CO2 (vol/vol) in air. Agar cultures were fixed with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, stained for acetylcholinesterase and with Luxol fast blue and hematoxylin. The cellular composition of each colony was determined at a magnification of 100× to 400×. Methylcellulose cultures were stained with 2,7-diaminofluorene (DAF).

Thrombopoietin Analysis.

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, allowed to coagulate at room temperature for 2 h, centrifuged at 5,500 rpm for 20 min, and serum collected. Thrombopoietin (TPO) levels were measured by ELISA using the Quantikine Mouse TPO Immunoassay kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Platelet Clearance Studies.

Platelet life span was analyzed as described in ref. 24. Briefly, mice were injected intravenously with 600 μg N-hydroxysuccinimidobiotin (NHS-biotin) (Sigma–Aldrich) in buffer containing 10% DMSO. For adoptive transfer experiments, blood obtained by cardiac puncture 1 h after injection of NHS-biotin, was mixed with 0.1 vol anticoagulant [85 mM sodium citrate dihydrate, 69 mM citric acid anhydrous, and 2% (wt/v) glucose] and then platelets isolated by multiple centrifugation steps (2 × 8 min, 125 × g followed by 2 × 5 min, 860 × g) in 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 12 mM sodium citrate, 10 mM glucose, and 12.5 mM sucrose, pH 6.0. Platelets were pooled and resuspended in 10 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4, before i.v. injection into recipient mice. At specific time points, 2 μL whole tail blood was stained with anti-CD41-FITC and streptavidin-PE (BD) and platelets analyzed by flow cytometry.

Megakaryocyte Ploidy Assays.

Bone marrow was harvested from 8–10-week-old mice into CATCH buffer [calcium and magnesium free Hank's buffered salt solution, 3% FCS (vol/vol), 3% BSA (wt/vol), 0.38% sodium citrate (wt/vol), 1 mM adenosine, and 2 mM theophylline] and centrifuged at 500 rpm for 5 min then stained with rat anti-CD41 (BD) and propidium iodide. Cells were washed, RNase treated, and analyzed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD).

Electron Microscopy.

After perfusion of mice with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (vol/vol) and 2% paraformaldehyde (vol/vol) in 0.1 M PBS (PBS, pH 7.4) via the descending dorsal aorta, femurs were removed, immersion-fixed overnight, and decalcified in 270 mM aqueous EDTA (pH 7.4) at 4 °C over 10 days. Bones were washed in 0.1 M PBS/5% sucrose (wt/vol), postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide (wt/vol) in 0.1 M PBS, and rinsed then dehydrated with graded concentrations of ethanol before infiltration and embedding in Spurr's resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with both methanolic uranyl acetate and lead citrate before viewing in a transmission electron microscope, JEOL 1011 at 60 kV. Images were collected using a Megaview-III CCD camera (Soft Imaging Systems) and ITEM acquisition software (ITEM Software).

Bone Marrow Transplantation.

Recipient mice 7–12 weeks of age were given 11 Gy of γ-irradiation. Unfractionated femoral donor bone marrow was suspended in a balanced salt solution (0.15 M NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, 0.8 mM K2HPO4, and 15 mM Hepes) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) bovine calf serum (Bovogen) and administered intravenously to recipient mice at the indicated doses in a volume of 200 μL. Chimerism in the blood was determined by flow cytometry utilising Ly5 polymorphisms between donor and recipient mice (25). For colony forming unit-spleen (CFU-S) assays, spleens were fixed in Carnoy's solution [60% ethanol (vol/vol), 30% chloroform (vol/vol), 10% acetic acid (vol/vol)], and macroscopic colonies counted.

Analysis of Hematopoietic Stem Cells.

Bone marrow from 8- to 10-week-old mice was incubated with rat monoclonal antibodies to the lineage markers CD3, CD19, B220, CD11b, Gr-1, CD2, CD8, and Ter119 (prepared in our laboratories) and stained with anti-rat Ig Alexa Fluor 680 (Alexis Biochemicals) to exclude lineage-positive cells. Cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies to Sca-1, c-Kit CD34, and Flt3 (BD) for analysis on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD).

Statistical Analyses.

The two-tailed Welch's t test was used for all statistical analyses. P values were adjusted by the Bonferroni correction where multiple tests were performed on the same sample.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Katya Henley, Jason Corbin, Rachael Lane, and Stephen Asquith for excellent technical assistance; Kelly Trueman, Mathew Salzone, Shauna Ross, Chris Evans, Jackie Gilbert, and Melissa Smith for expert animal husbandry; and Nicos Nicola and Samir Taoudi for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a Program Grant (461219), Project Grant (516726), Fellowships (to D.J.H., W.S.A., B.T.K.) and Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme Grant (361646) from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, a Fellowship from the Australian Research Council (to B.T.K.), a Fellowship from the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation (to B.T.K.), the Carden Fellowship Fund of the Cancer Council - Victoria (D.M.), a University of Melbourne Scholarship (to E.A.K.), an Australian Department of Education, Science and Training Scholarship (to S.J.L.), a fellowship from the Swedish Research Council (to E.C.J.), a fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (to E.C.J.), the Australian Cancer Research Fund, and a Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0906556106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sharrocks AD, Brown AL, Ling Y, Yates PR. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:1371–1387. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delattre O, et al. Gene fusion with an ETS DNA-binding domain caused by chromosome translocation in human tumours. Nature. 1992;359:162–165. doi: 10.1038/359162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-David Y, Giddens EB, Bernstein A. Identification and mapping of a common proviral integration site Fli-1 in erythroleukemia cells induced by Friend murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1332–1336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart A, et al. Fli-1 is required for murine vascular and megakaryocytic development and is hemizygously deleted in patients with thrombocytopenia. Immunity. 2000;13:167–177. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spyropoulos DD, et al. Hemorrhage, impaired hematopoiesis, and lethality in mouse embryos carrying a targeted disruption of the Fli1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5643–5652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5643-5652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raslova H, et al. FLI1 monoallelic expression combined with its hemizygous loss underlies Paris-Trousseau/Jacobsen thrombopenia. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:77–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI21197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pimanda JE, et al. Gata2, Fli1, and Scl form a recursively wired gene-regulatory circuit during early hematopoietic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17692–17697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707045104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottgens B, et al. Establishing the transcriptional programme for blood: The SCL stem cell enhancer is regulated by a multiprotein complex containing Ets and GATA factors. EMBO J. 2002;21:3039–3050. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorensen PH, et al. A second Ewing's sarcoma translocation, t(21;22), fuses the EWS gene to another ETS-family transcription factor, ERG. Nat Genet. 1994;6:146–151. doi: 10.1038/ng0294-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu K, et al. An ets-related gene, ERG, is rearranged in human myeloid leukemia with t(16;21) chromosomal translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10280–10284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomlins SA, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loughran SJ, et al. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:810–819. doi: 10.1038/ni.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginsberg JP, et al. EWS-FLI1 and EWS-ERG gene fusions are associated with similar clinical phenotypes in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1809–1814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrere S, Verger A, Flourens A, Stehelin D, Duterque-Coquillaud M. Erg proteins, transcription factors of the Ets family, form homo, heterodimers and ternary complexes via two distinct domains. Oncogene. 1998;16:3261–3268. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera RR, Stuiver MH, Steenbergen R, Murre C. Ets proteins: New factors that regulate immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7163–7169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breton-Gorius J, et al. A new congenital dysmegakaryopoietic thrombocytopenia (Paris-Trousseau) associated with giant platelet alpha-granules and chromosome 11 deletion at 11q23. Blood. 1995;85:1805–1814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, et al. Identification of Lin(-)ScaI(+)kit(+)CD34(+)Flt3- short-term hematopoietic stem cells capable of rapidly reconstituting and rescuing myeloablated transplant recipients. Blood. 2005;105:2717–2723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawada H, et al. Defective megakaryopoiesis and abnormal erythroid development in Fli-1 gene-targeted mice. Int J Hematol. 2001;73:463–468. doi: 10.1007/BF02994008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pang L, et al. Maturation stage-specific regulation of megakaryopoiesis by pointed-domain Ets proteins. Blood. 2006;108:2198–2206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-019760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overholtzer M, Brugge JS. The cell biology of cell-in-cell structures. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:796–809. doi: 10.1038/nrm2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pimanda JE, et al. Endoglin expression in the endothelium is regulated by Fli-1, Erg, and Elf-1 acting on the promoter and a −8-kb enhancer. Blood. 2006;107:4737–4745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao VN, Ohno T, Prasad DD, Bhattacharya G, Reddy ES. Analysis of the DNA-binding and transcriptional activation functions of human Fli-1 protein. Oncogene. 1993;8:2167–2173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexander WS, Roberts AW, Nicola NA, Li R, Metcalf D. Deficiencies in progenitor cells of multiple hematopoietic lineages and defective megakaryocytopoiesis in mice lacking the thrombopoietic receptor c-Mpl. Blood. 1996;87:2162–2170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason KD, et al. Programmed anuclear cell death delimits platelet life span. Cell. 2007;128:1173–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen FW, et al. Cloning of Ly-5 cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7360–7363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.