Abstract

Rapid and accurate measurement of biomarkers in tissue and fluid samples is a major challenge in medicine. Here we report the development of a new, miniaturized diagnostic magnetic resonance (DMR) system for multiplexed, quantitative and rapid analysis. By using magnetic particles as a proximity sensor to amplify molecular interactions, the handheld DMR system can perform measurements on unprocessed biological samples. We show the capability of the DMR system by using it to detect bacteria with high sensitivity, identify small numbers of cells and analyze them on a molecular level in real time, and measure a series of protein biomarkers in parallel. The DMR technology shows promise as a robust and portable diagnostic device.

A number of new diagnostic platforms have been developed to measure biomolecule abundance with high sensitivity1, enable early disease detection2 and gain valuable insights into biology at the systems level3. Some examples include nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) with hyperpolarized gas4, nanowire5 and nanoparticle6 sensors, surface plasmon resonance devices7 and mass spectrometry8. Many of these devices and techniques, however, requiring time-consuming purification of samples typically followed by a set of amplification strategies6, may lack the ability for the multiplexed measurements that are desirable in identifying complex diseases1,9 or may not be amenable for easy point-of-care translation.

Here we report a chip-based DMR system for rapid, quantitative and multichanneled detection of biological targets. Using readily available magnetic nano- and microparticles as a proximity sensor to amplify molecular interactions10, the DMR system can perform highly sensitive (up to 1 × 10−12 M) and selective measurements on small volumes of unprocessed biological samples. As proof of concept, we show sensitive detection of bacteria, profiling of circulating cells and multiplexed identification of different cancer biomarkers. If implemented with standard microfabrication technology, the DMR system will be a high-throughput, low-cost and portable platform for large-scale sensing.

The DMR sensor strategy is based on a self-amplifying proximity assay using magnetic nanoparticles10. When a few magnetic nanoparticles bind their intended molecular target through affinity ligands, they form soluble nanoscale clusters, which leads to a corresponding decrease in the bulk spin-spin relaxation time (T2) of surrounding water molecules. Notably, because the assay uses NMR techniques for signal detection, measurements can be performed in turbid samples (for example, blood, sputum and urine) with few or no preparation steps. Data can be acquired electronically without relying on bulky optical components, and the sensing procedure is faster than that with surface structure–based devices whose operation relies on molecular diffusion of targets to sensing elements11. These advantages render the proximity assay ideal for fast, simple and high-throughput sensing operations, especially in miniaturized device format. To date, however, measurements have relied primarily on clinical or benchtop NMR systems requiring large sample volumes and complex data acquisition. We hypothesized that with standard microfabrication technology, a chip-based NMR system could be implemented to perform measurements on small sample volumes in a multiplexed fashion. Miniaturizing an entire NMR system, including the source of external magnetic fields, was technically challenging, mainly owing to the low NMR signal level intensity coming from the small sample volume and low magnetic field strength. We have overcome these limits by optimizing the design of the NMR system and by introducing microfluidics onto the NMR chip12–14.

Results

Design of the DMR system

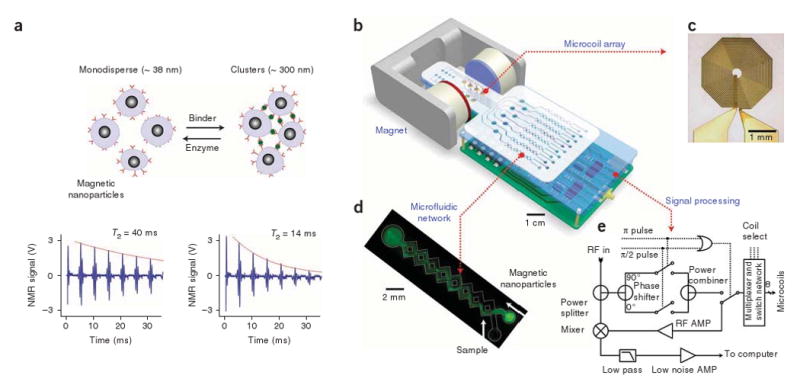

Conceptually, the DMR system consists of four major components (Fig. 1): a microNMR (μNMR) chip containing microcoils, a microfluidic network for sample handling, on-board NMR electronics and a small permanent magnet. For multichanneled detection, we chose to arrange multiple planar microcoils in an array rather than implement field gradient coils, as the former method scales down favorably with device miniaturization. The microfluidic system facilitates control and manipulation of small volumes of liquid and can provide additional magnetic separation and concentration of targets from a complex parent specimen. For tight control of temperature, heating elements with temperature sensors can be incorporated into the microfluidic system. Because the sensing components are small, portable permanent magnets can be used to generate polarizing magnetic fields, B0 = 0.1–0.5 T. The whole DMR system, therefore, can be designed as a self-contained and portable device. The on-board electronics can be integrated in a single complementary metal oxide semiconductor transceiver chip, further reducing the device size.

Figure 1.

Principle of the assay and structure of the DMR system. (a) Principle of proximity assay using magnetic particles. When monodisperse magnetic nanoparticles cluster upon binding to targets, the self-assembled clusters become more efficient at dephasing nuclear spins of many surrounding water protons, leading to a decrease in spin-spin relaxation time (T2). The bottom panel shows an example of the proximity assay measured by the DMR system. Avidin was added to a solution of biotinylated magnetic nanoparticles, causing T2 to decrease from 40 ms to 14 ms. (b) Schematic diagram of the DMR system. The system consists of an array of microcoils for NMR measurements, microfluidic networks for sample handling and mixing, miniaturized NMR electronics and a permanent magnet to generate a polarizing magnetic field. The entire setup can be packaged as a handheld device for portable operation (for clarity, the structure of the magnet is simplified). (c) High resolution image of an actual microcoil. The microcoil generates radio frequency (RF) magnetic fields to excite samples and receives the resulting NMR signal. To reduce electrical resistance and hence thermal noise, the metal lines were electroplated with copper. (d) Example of a microfluidic network. Effective mixing between magnetic particles and the target analytes is achieved by generating chaotic advection through the meandering channels. The channel also helps confine the mixture in the most sensitive region of the microcoils, increasing filling factors. (e) Schematic of the NMR electronics. The circuit is designed to perform T2 and T1 measurements via CPMG and inversion-recovery pulse sequences, respectively. AMP, amplifier.

In our first prototype, we implemented a DMR system that can perform eight-multiplexed measurements in 5–10-μl sample volumes. A μNMR chip containing a 2 × 4 planar microcoil array was fabricated on a glass substrate using standard microfabrication technology (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1 online). The microcoils were used for both radio frequency excitation and NMR signal detection. When a direct current is applied, the microcoils can also be used to environmentally heat samples and to concentrate magnetically labeled targets by forming magnetic traps15. We tuned the sensor (Supplementary Fig. 2 online) to operate at B0 = 0.5 T (21.3 MHz), generated by a portable permanent magnet. Custom-made NMR electronics provided pulse sequences to measure the longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times (Fig. 1e). We measured the T1 relaxation time using inversion recovery pulse sequences; for T2 measurements, we used Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) spin-echo pulse sequences (see Fig. 1a for example) to compensate for the inhomogeniety of the polarizing magnetic field (∼8 × 10−5 T). We determined the pulse widths for 90° and 180° flip of nuclear spins by generating nutation curves for each microcoil (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3 online).

The microfluidic network in the DMR system provides vital functions in the sensing process, including handling of biological fluids, reproducible mixing of magnetic nanoparticles with samples, distribution of aliquots to different coils for parallel sensing and confining samples to the most sensitive region of a given microcoil. Figure 1d shows one specific, simplified example of a microfluidic system that consists of a cylindrical chamber and two meandering, three-dimensional channel networks16. The chamber was placed on top of a planar microcoil to contain samples in close proximity to the coil. We optimized the radius and the height of the chamber for maximal NMR signal detection with minimal sample volume (Supplementary Fig. 4 online). The microfluidic channels provided effective fluid mixing through chaotic advection between different input fluids. For fast prototyping, we fabricated microfluidic systems by patterning polymethylmethacrylate substrates using a CO2 laser. Depending on specific experiment purposes, different microfluidic systems can be integrated on top of the microcoils.

System benchmarking and detection limit

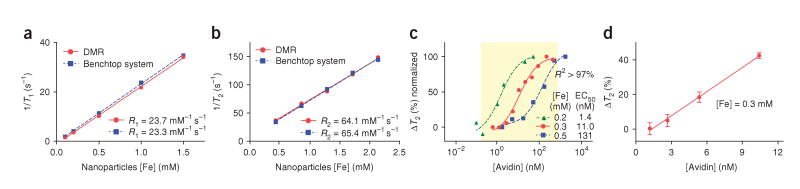

We determined the accuracy of the DMR system by comparing its performance to a large benchtop NMR relaxometer that measures T1 and T2 at a similar B0 (0.47 T, 20 MHz). The observed longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxivities (relaxation rate per iron concentration) of water containing magnetic nanoparticles showed excellent agreement (Fig. 2a,b). The benchtop system requires sample volumes of >300 μl and is able to process one specimen at a time. For the DMR system, the sample volume per coil is ∼5 μl, and many coils can independently perform measurements in a multiplexed fashion; the number of simultaneous measurements is theoretically limited by the number of coils per chip.

Figure 2.

Accuracy and sensitivity of the DMR system. (a,b) The accuracy of the DMR system for T1 (a) and T2 (b) measurements was benchmarked against a commercial benchtop relaxometer. The measured values show excellent agreements. (c) Biotinylated magnetic nanoparticles were incubated with different amounts of avidin, which resulted in the avidin concentration–dependent change of T2. By varying the concentration of magnetic nanoparticles, four orders of dynamic ranges were achieved. Data were fitted to sigmoidal curves (R2 > 97%). EC50, effective concentration for half-maximal response. (d) The DMR system showed greatly enhanced mass sensitivity over the benchtop relaxometer, detecting ∼1.0 ng (15 fmol, 3 nM) avidin in a 5-μl sample in this particular experiment. The improved mass sensitivity comes from the device miniaturization, which enables stronger radio frequency field generation with increased filling factors in small volumes of samples. By switching from magnetic nanoparticles to micrometer-sized particles and other amplification means, detection thresholds of ∼1 pM have been achieved (Supplementary Methods). All data are shown as means ± s.e.m.

We characterized the detection sensitivity of the DMR system using avidin-biotin interactions. We added increasing amounts of avidin to biotinylated magnetic nanoparticles, which led to the formation of larger clusters and concomitant decreases in the T2 of the surrounding water. By varying the concentration of magnetic nanoparticles, we achieved detection dynamic ranges spanning up to four orders of magnitude (Fig. 2c). Compared to the benchtop relaxometer, the DMR system showed a mass detection limit improved by two orders of magnitude; the benchtop relaxometer was able to detect ∼80 ng (1.2 pmol, 4 × 10−9 M) of avidin, whereas the DMR system had a detection limit of ∼1.0 ng (15 fmol, 3 × 10−9 M), a more than 80-fold increase in mass sensitivity (Fig. 2d). Of note, other assay configurations using the same DMR device can yield much higher detection sensitivities both on mass and on concentration. For example, with micrometer-sized magnetic particles, we were able to achieve detection limits of ∼1 × 10−12 M (mouse IgG to Tag peptide)17, similar to or surpassing detection limits by ELISA (Supplementary Methods online).

The high mass sensitivity of the DMR system can be attributed to the microcoil, which produces strong radio frequency magnetic fields per unit electrical currents12, the microfluidic systems which place the target samples in the most sensitive regions around the microcoils, increasing the filling factor (Supplementary Fig. 4), and the miniaturization of the NMR probe that permits the decrease in sample volumes to be tested18. The DMR system is thus well suited to detect analytes in mass-limited biological samples and to preserve expensive analytes. Our ongoing efforts to further improve the detection sensitivity include optimization of the geometry and reducing the electrical resistance of the microcoils, monolithic integration of the signal detection circuitry in a single integrated circuit chip19 to reduce external interferences and signal losses, development of new magnetic nanoparticles with higher R2 relaxivity20, and design and construction of new permanent magnet assemblies21,22 to increase the strength of the polarizing magnetic field (B0) for enhanced NMR signal level.

Rapid detection of bacteria

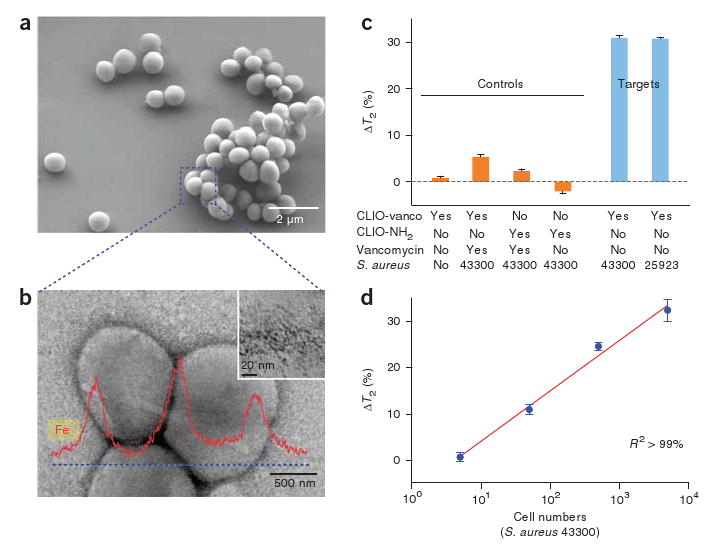

One of the compelling applications of the DMR system is the rapid detection and characterization of infectious agents including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Robust and miniaturized diagnostics tools for infection could have a high impact not only on basic biomedical and pharmaceutical research23 but also on global healthcare, especially in developing countries24. As proof of concept, we determined the sensitivity of DMR for detecting bacteria, using Staphylococcus aureus (Fig. 3a) as a model organism. Magnetic nanoparticles derivatized with vancomycin, which binds d-alanyl-d-alanine moieties in the bacterial cell wall25, served as a sensor. After incubation with bacteria, we found the nanoparticles attached to the bacterial cell wall in dense, clustered sheets (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5 online). Indeed, we observed concentration-dependent T2 decreases in samples with different S. aureus strains (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Table 2 online). With its high mass sensitivity and its use of small sample volume, the DMR system was able to detect as few as ten bacteria in a 10-μl sample, with the detection ranges spanning at least three orders of magnitude (Fig. 3d). Notably, the DMR measurements were markedly faster (< 15 min) and simpler than cultivation- or nucleic acid–based analytic methods. By modifying the clustering analytes on the magnetic nanoparticles, one could use the DMR to selectively detect different infectious agents in various media, for example, mycobacterium in sputum26, enterotoxic bacteria in water supplies27 or respiratory pathogens28 in point-of-care settings. These advantages make the DMR an ideal diagnostic tool for fast identification of pathogens especially in resource-limited settings.

Figure 3.

Sensitive detection of bacteria. Potential application of the DMR system as a simple, rapid diagnostic tool for infectious pathogens is shown with S. aureus as a model organism and magnetic nanoparticles derivatized with vancomycin (CLIO-vanco) as sensors. (a) Scanning electron micrograph of S. aureus. (b) Transmission electron micrograph of S. aureus. Magnetic nanoparticles (CLIO-vanco) formed dense clusters on the bacterial cellular membrane (inset). Element analysis by energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (along the dotted line) further confirmed the binding of the nanoparticles to the bacteria. (c) Bacteria detection by the DMR system. Whereas the control samples with composition shown in the matrix did not show significant T2 changes, consistent decreases in T2 were observed with different strains of S. aureus. CLIO-NH2, unmodified magnetic nanoparticle. (d) Changes of T2 with varying number of bacteria. The DMR system in this configuration had a detection sensitivity of about one colony-forming unit per microliter with dynamic ranges over three orders of magnitude. DMR measurements were markedly faster (< 15 min) than culture- (days) or nucleic acid (hours)-based molecular techniques. ΔT2 is shown as mean ± s.e.m.

Analysis of mammalian cells and the measurement of biomarkers

Another key potential application of the DMR system is the profiling of mammalian cells and the multichanneled detection of protein biomarkers in native biological samples. Detecting multiple biomarkers and circulating cells in human body fluids is an especially crucial task for diagnosis and prognosis of complex diseases such as cancer and metabolic disorders9. To evaluate the efficacy of the DMR system as a probing tool for complex diseases, we addressed whether mammalian cells could indeed be detected in serum samples, whether tumor cells could be profiled by targeting surface receptors and whether it would be feasible to perform multiplexed measurements in a screening mode.

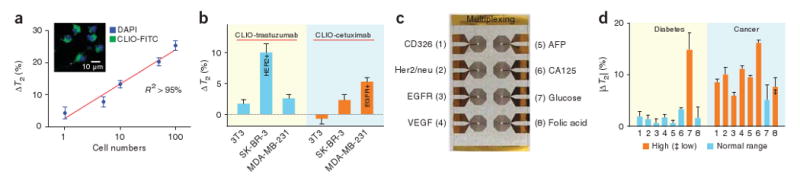

We first explored the detection limit of mammalian cells using mouse macrophages (RAW 264.7) as a model cell line. We incubated the cells with magnetic nanoparticles to exploit the efficient phagocytosis of this cell line as a means of labeling (Fig. 4a). After washing off unbound magnetic particles, we resuspended cells and counted them. Samples with different cell concentrations were prepared by serial dilution and T2 was measured on 10-μl volumes. As expected, we observed more prominent T2 changes as the cell number increased (Fig. 4a). Most notably, a single cell could be detected (P < 0.0001), which indicates that the DMR system could be applied toward identifying rare cells such as circulating tumor cells, stem cells or immune cells in blood29.

Figure 4.

Profiling of mammalian cells. (a) Mouse macrophages (RAW 264.7) were incubated with magnetic nanoparticles (CLIO-FITC; inset) to determine cellular detection thresholds. A single cell in a 10- μl sample volume could be detected. (b) Cancer cell profiling by targeting cell surface markers. Magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with monoclonal antibodies to target Her2/neu and EGFR (CLIO-trastuzumab and CLIO-cetuximab, respectively) were incubated with breast cancer cells (positive control) or fibroblast cells (3T3, negative control). A larger decrease in T2 was observed with cell lines that overexpressed the targeted surface makers (SK-BR-3 for Her2/neu and MDA-MB-231 for EGFR). The measurements were performed on ∼1 × 104 cells in a 10-μl sample volume. (c,d) Detection of multiple biomarkers. A prototype microcoil array was designed for eight multiplexed measurements and detection targets were assigned (c). Magnetic nanoparticles for each target were conjugated with the corresponding antibodies or proteins. Normal, diabetic and cancer sera were prepared by adding the relevant markers to serum (Supplementary Table 4). Analysis of sera (d) shows the detection of abnormally high amounts of biomarkers in the samples; abnormally low amount of folic acid was detected in cancer serum as indicated by ‡. ΔT2 is shown as mean ± s.e.m. VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; AFP, α-fetoprotein; CA125, cancer antigen-125.

We next profiled cancer cells by targeting the epidermal growth factor receptors EGFR and Her2/neu (Fig. 4b). Magnetic nanoparticles, derivatized with the corresponding monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab for EGFR, trastuzumab for Her2/neu), were incubated for 30 min with breast cancer cells (SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-231; positive control) and fibroblasts (negative control). After washing off unbound magnetic nanoparticles and suspending the cells in serum, we measured T2 in 10-μl samples containing ∼1 × 104 cells. We were able to selectively detect both cell surface markers (Her2/neu in SK-BR-3 and EGFR in MDA-MB-231; Fig. 4b). Compared to the single-cell detection experiment described above (Fig. 4a), a larger number of cells was required to detect measurable changes in T2, possibly because the number of nanoparticles bound per cell was lower. We anticipate achieving further increases in measurement sensitivity by using alternative magnetic particles of different sizes and compositions and with higher R2 relaxivity20.

We next showed the potential application of the DMR system for multiplexed screening with a 2 × 4 microcoil array. We assigned eight detection markers, one per each microcoil (Fig. 4c). We prepared magnetic nanoparticles conjugated with corresponding antibodies or proteins (Supplementary Table 3 online) and concocted serum specimens mimicking those from healthy individuals, individuals with diabetes and individuals with cancer by adding relevant markers into normal serum (Supplementary Table 4 online). The results (Fig. 4d) illustrate how different serum conditions can be identified from the multiplexed screening.

Discussion

We have developed a miniaturized DMR platform consisting of planar microcoils, microfluidic channels and a portable magnet. The microcoils were arranged in an array format for parallel, multiplexed detection; the microfluidic channels were optimized to generate maximal NMR signal with small sample volumes (5–10 μl). Using this DMR prototype, we were able to achieve high mass-detection sensitivity compared to a benchtop relaxometer (>80,000% improvement). We have shown the utility and exquisite sensitivity of the DMR system by detecting a few bacteria, profiling cancer cells and identifying protein biomarkers in a multiplexed fashion (summarized in Supplementary Table 5 online).

The described DMR system represents a distinctive combination of two core technologies: device miniaturization through microfabrication and molecular proximity assays using magnetic nanoparticles. Device miniaturization enables a considerable reduction in the sample volume, leading to the marked increase in detection sensitivity. Multiplexed measurements can also be performed for the fast and accurate screening of complex diseases. Because the DMR system is implemented through standard microfabrication, it can be readily mass produced as a low-cost, disposable unit. The use of magnetic nanoparticles brings inherent signal amplification (that is, detection of T2 changes in billions of water molecules adjacent to a single clustered nanoparticle) and the ability to detect signal in opaque biological media that are transparent to magnetic fields.

In an effort to further improve the detection sensitivity of the DMR system, we have begun to synthesize new classes of water-soluble magnetic particles with higher magnetization. These particles are expected to be more efficient at dephasing water protons, resulting in increased detection sensitivity17. Additional advances have been made in the miniaturization of the device. For example, we have recently integrated the entire NMR electronics in a single complementary metal oxide semiconductor chip30. Finally, efforts are under way to fabricate larger detector arrays (>100 microcoils) for high-throughput assays. We anticipate the resulting DMR systems will be broadly applicable to sensing different biomarkers and biological species with enhanced sensitivity and specificity, and will be a truly portable, easy-to-use and low-cost device for point-of-care use.

Methods

Construction of the nuclear magnetic resonance system

We used standard microfabrication techniques, including photolithography and electroplating, to build microcoil arrays. We chose glass wafers as a substrate to minimize signal loss. Coil patterns were lithographically defined and then electroplated with copper to reduce electrical resistance (Supplementary Fig. 1). The outer diameter of each microcoil was 2 mm and the distance between two adjacent coils in each array was 2 mm. After fabrication was completed, the wafer was diced into chips containing 2 × 4 microcoils. Patterns of microfluidic channels were directly cut through on a polymethylmethacrylate sheet with a laser (Boston Lasers). To construct the mixing channel (Fig. 1d), we aligned and bonded two fluidic channel layers and a cover layer. The microfluidic system was then attached on top of the microcoil array chip.

Overall system design

We mounted the assembled NMR probe on a printed circuit board that contained impedance-matching capacitors and multiplexing circuits. We installed the printed circuit board and a permanent dipole magnet (PM1055-050N, Metrolab) on a custom-made plastic platform. The NMR electronics (Fig. 1e) were constructed with discrete components (for example, AD9830 for radio frequency generation and AD604 for NMR signal amplification; Analog Device). We connected the NMR electronics to a computer through a plug-in card (NI PCI-6042E, National Instruments) to generate pulse sequences and to acquire data.

Preparation of magnetic nanoparticles

We used cross-linked iron oxide (CLIO) as the main magnetic nanoparticle for molecular and cellular measurements. The hydrodynamic diameter of CLIO in aqueous solution, measured by dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer 1000HS; Malvern Instruments), was 38 nm. The R1 and R2 relaxivities were 21 mM−1 s−1 and 62 mM−1 s−1, respectively (Minispec mq20; Bruker) at 40 °C and 0.47 T. We used primary amine groups on the nanoparticle surface for conjugation to different molecules or antibodies: biotin (target, avidin), vancomycin (S. aureus), glucose (glucose), folic acid (folic acid) and the corresponding antibodies (to EGFR, Her2/neu, CD326, vascular endothelial growth factor, cancer antigen-125, and α-fetoprotein). For RAW cell detection, we used the amine-terminated CLIO without any modification. Detailed protocols on particle preparation are available in the Supplementary Methods.

Relaxation measurement

We performed T2 measurements on 5–10-μl samples using CPMG pulse sequences with the following parameters: echo time, 4 ms; repetition time, 1 s; the number of 180° pulses per scan, 36; the number of scans, 64. For mammalian cell detection, we increased the number of 180° pulses to 250 with a repetition time of 6 s to accommodate longer T2. We carried out all measurements at room temperature (20 °C) in triplicate (quintuplicate for RAW cell detection). Data were displayed as mean ± s.e.m. In the multiplexed detection mode, we performed measurements (pulsing a microcoil and monitoring the subsequent NMR signal) in series for each microcoil. The on-board multiplexer controlled by a computer selected a specific microcoil. One microcoil was connected to the NMR electronics at any given moment, reducing signal bleed-through between coils. The total measurement time for an eight-microcoil array was < 10 min. Assay conditions for each target (Fig. 4c,d) are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Additional methods

Details on device fabrication, synthesis and derivation of magnetic particles, and experimental protocols are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge N. Sergeyev for synthesizing CLIO, K. Kelly, K. Kristof and S. Thomas for cell culture and I. Koh for help in magnetic microparticle–based assay. We especially thank L. Josephson, J. Bradner and M. Cima for many helpful suggestions, R.M. Westervelt for generous support in device fabrication and D.S. Yun and A. Belcher for assistance in imaging bacteria with a transmission electron microscope.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Medicine website.

Author Contributions: H.L. designed the device, built the DMR prototype, obtained measurements, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. E.S. performed all chemical modifications of magnetic nanoparticles and assisted in measurements and data analysis. D.H. collaborated in the development of the NMR electronics of discrete components. R.W. conceived the project, provided overall guidance, designed experiments and targeted nanoparticles, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Competing Interests Statement: The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the full-text HTML version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/naturemedicine/.

References

- 1.Cheng MMC, et al. Nanotechnologies for biomolecular detection and medical diagnostics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wulfkuhle JD, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Proteomic applications for the early detection of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:267–275. doi: 10.1038/nrc1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hood L, Heath JR, Phelps ME, Lin B. Systems biology and new technologies enable predictive and preventative medicine. Science. 2004;306:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroder L, Lowery T, Hilty C, Wemmer D, Pines A. Molecular imaging using a targeted magnetic resonance hyperpolarized biosensor. Science. 2006;314:446–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1131847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng G, Patolsky F, Cui Y, Wang W, Lieber C. Multiplexed electrical detection of cancer markers with nanowire sensor arrays. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1294–1301. doi: 10.1038/nbt1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nam JM, Thaxton C, Mirkin C. Nanoparticle-based bio-bar codes for the ultrasensitive detection of proteins. Science. 2003;301:1884–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1088755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aslan K, Lakowicz JR, Geddes CD. Plasmon light scattering in biology and medicine: new sensing approaches, visions and perspectives. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry–based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidransky D. Emerging molecular markers of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:210–219. doi: 10.1038/nrc755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez JM, Josephson L, O'Loughlin T, Hogemann D, Weissleder R. Magnetic relaxation switches capable of sensing molecular interactions. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:816–820. doi: 10.1038/nbt720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair PR, Alam MA. Performance limits of nanobiosensors. Appl Phys Lett. 2006;88:233120–233123. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peck TL, Magin RL, Lauterbur PC. Design and analysis of microcoils for NMR microscopy. J Magn Reson B. 1995;108:114–124. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massin C, et al. Planar microcoil-based microfluidic NMR probes. J Magn Reson. 2003;164:242–255. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(03)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trumbull JD, Glasgow IK, Beebe DJ, Magin RL. Integrating microfabricated fluidic systems and NMR spectroscopy. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2000;47:3–7. doi: 10.1109/10.817611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H, Liu Y, Westervelt RM, Ham D. IC/microfluidic hybrid system for magnetic manipulation of biological cells. IEEE J Solid-State Circuits. 2006;41:1471–1480. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia HM, Wan SYM, Shu C, Chew YT. Chaotic micromixers using two-layer crossing channels to exhibit fast mixing at low Reynolds numbers. Lab Chip. 2005;5:748–755. doi: 10.1039/b502031j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh I, Hong R, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Sensitive NMR sensors detect antibodies to influenza. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:4119–4121. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson DL, Peck TL, Webb AG, Magin RL, Sweedler JV. High-resolution microcoil 1H-NMR for mass-limited, nanoliter-volume samples. Science. 1995;270:1967–1970. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boero G, de Raad Iseli C, Besse PA, Popovic RS. An NMR magnetometer with planar microcoils and integrated electronics for signal detection and amplification. Sens Actuators A. 1998;67:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JH, et al. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nat Med. 2007;13:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halbach K. Design of permanent multipole magnets with oriented rare earth cobalt material. Nucl Instrum Methods. 1980;169:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perlo J, Casanova F, Blumich B. Ex situ NMR in highly homogeneous fields: 1H spectroscopy. Science. 2007;315:1110–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1135499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dittrich PS, Manz A. Lab-on-a-chip: microfluidics in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:210–218. doi: 10.1038/nrd1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urdea M, et al. Requirements for high impact diagnostics in the developing world. Nature. 2006;444(suppl 1):73–79. doi: 10.1038/nature05448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barna JC, Williams DH. The structure and mode of action of glycopeptide antibiotics of the vancomycin group. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:339–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keeler E, et al. Reducing the global burden of tuberculosis: the contribution of improved diagnostics. Nature. 2006;444(suppl 1):49–57. doi: 10.1038/nature05446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci KA, et al. Reducing stunting among children: the potential contribution of diagnostics. Nature. 2006;444(suppl 1):29–38. doi: 10.1038/nature05443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim YW, et al. Reducing the global burden of acute lower respiratory infections in children: the contribution of new diagnostics. Nature. 2006;444(suppl 1):9–18. doi: 10.1038/nature05442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cristofanilli M, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:781–791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Sun N, Lee H, Weissleder R, Ham D. CMOS mini nuclear magnetic resonance system and its application for biomolecular sensing. ISSCC Dig Tech Papers. 2008;1:140–141. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.