Abstract

Purpose

Ductal lavage has been used for risk stratification and biomarker development and to identify intermediate endpoints for risk-reducing intervention trials. Little is known about patient characteristics associated with obtaining nipple aspirate fluid (NAF) and adequate cell counts (≥10 cells) in ductal lavage specimens from BRCA mutation carriers.

Methods

We evaluated patient characteristics associated with obtaining NAF and adequate cell counts in ductal lavage specimens from the largest cohort of women from BRCA families yet studied (BRCA1/2 = 146, mutation-negative = 23, untested = 2). Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate categorical variables; Wilcoxon nonparametric test was used to evaluate continuous variables associated with NAF or ductal lavage cell count adequacy. Logistic regression was used to identify independent correlates of NAF and ductal lavage cell count adequacy.

Results

From 171 women, 45 (26%) women had NAF and 70 (41%) women had ductal lavage samples with ≥10 cells. Postmenopausal women with intact ovaries compared with premenopausal women [odds ratio (OR), 4.8; P = 0.03] and women without a prior breast cancer history (OR, 5.2; P = 0.04) had an increased likelihood of yielding NAF. Having breast-fed (OR, 3.4; P = 0.001), the presence of NAF before ductal lavage (OR, 3.2; P = 0.003), and being premenopausal (OR, 3.0; P = 0.003) increased the likelihood of ductal lavage cell count adequacy. In known BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, only breast-feeding (OR, 2.5; P = 0.01) and the presence of NAF (OR, 3.0; P = 0.01) were independent correlates of ductal lavage cell count adequacy.

Conclusions

Ductal lavage is unlikely to be useful in breast cancer screening among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers because the procedure fails to yield adequate specimens sufficient for reliable cytologic diagnosis or to support translational research activities.

Introduction

Ductal lavage is a technique developed to collect breast epithelial cells from the breast duct lining using a small catheter inserted into a breast nipple ductal orifice. It was aimed at increasing the numbers of epithelial cells collected from breasts for use in early detection of invasive and noninvasive breast cancer, assessing breast cancer risk and developing biomarkers and intermediate endpoints for risk-reducing intervention trials (1). Several other techniques are available, including nipple aspirate fluid (NAF), breast ductal endoscopy, and random periareolar fine-needle aspiration, although the former yields very few cells and the latter two are relatively invasive procedures (1–3). Nonetheless, cellular atypia in NAF and random periareolar fine-needle aspirate specimens has been associated with an increased risk of noninvasive and invasive breast cancer (2–4). Reliably obtaining NAF from all or most women studied, and acquiring samples with cell counts adequate for cytologic evaluation (>10 evaluable cells) from ductal lavage specimens, has been a challenge (1, 5–12). Atypia has been detected in both NAF-yielding and non-NAF-yielding ducts from women at high risk of breast cancer (7, 10, 13, 14). Neither NAF production nor 5-year Gail risk >1.7% (15) predicted atypia in ductal lavage specimens from high-risk women (7, 16). Whether women with atypia detected by ductal lavage will show an increased prospective risk of breast cancer is unknown, and there is increasing evidence that reproducibility of cytologic diagnoses in benign duct epithelial specimens and in specimens with atypia found on ductal lavage is fair to poor (9, 11, 17).

Women who inherit a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation have an estimated lifetime breast cancer risk of 45% to 82% (18–21). Annual mammography and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly employed in the early detection of breast cancer in genetically predisposed women who do not undergo prophylactic mastectomy (22–27). Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, which lowers the risk of breast (as well as ovarian) cancer in BRCA mutation carriers (28–30), and tamoxifen-based chemoprevention are often considered as breast cancer risk-reducing strategies for these women (26, 28, 31–33). However, chemoprevention is neither widely used nor definitively proven effective in mutation carriers.

Several groups have reported their experience in obtaining NAF and performing ductal lavage in small numbers of women with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (13, 14, 34).We now report key patient variables associated with the ability to obtain NAF and adequate cell counts (>10 cells per sample) in ductal lavage samples in the largest cohort of women from families with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations yet studied.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We studied 204 women drawn from one of two institutional review board-approved National Cancer Institute protocols: “Breast Imaging Screening Studies in Women at High Genetic Risk of Breast Cancer: Annual Follow-up Study” (01-C-0009; n = 200) or Multidisciplinary Characterization of Individuals at High Risk of Breast/Ovarian Cancer (02-C-0212; n = 4; ref. 35). All participants received an annual mammogram, breast MRI, clinical breast examination, transvaginal ultrasound, CA-125, and ductal lavage. This report is a summary of the baseline ductal lavage experience of those subjects enrolled between June 2002 and February 2007.

Eligibility Criteria

Women were eligible if they were ages ≥25 years (Multidisciplinary Characterization of Individuals at High Risk of Breast/Ovarian Cancer) or between ages 25 and 56 years (“Breast Imaging Screening Studies in Women at High Genetic Risk of Breast Cancer: Annual Follow-up Study”) and (1) carried a known deleterious BRCA1/2 mutation, or (2) were first- or second-degree relatives of individuals with a deleterious BRCA1/2 mutation, or (3) were first- or second-degree relatives of individuals with BRCA-associated cancers in families with documented BRCA mutations. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or lactation within 6 months of enrollment, abnormal CA-125 level, breast cancer (bilateral, stage IIB or worse), or ovarian cancer unless relapse-free for 5 years before the time of enrollment (both breast and ovarian cancer). Participants with a personal history of ductal carcinoma in situ, stage I and II breast cancer were eligible provided that at least 6 months had elapsed from the completion of primary therapy (surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy). Participants with a personal history of ductal carcinoma in situ, stage I and II breast cancer plus a local relapse after primary treatment were eligible only if they were relapse-free for ≥5 years before enrollment. Other reasons for exclusion included a personal history of other invasive cancer unless relapse-free for ≥5 years before enrollment (except for nonmelanoma skin cancer or cervical carcinoma in situ), previous bilateral mastectomy or bilateral breast radiation therapy, weight >136 kg, or allergy to gadolinium. The following conditions excluded participants from ductal lavage: allergy to lidocaine or bupivacaine; subareolar or other surgery involving the breast to be studied, which might disrupt the ductal systems; a breast implant or prior silicone injections in the breast to be studied; prior radiation of the breast to be studied; and active infection or inflammation in a breast to be studied.

Participants were ascertained through various referral mechanisms: 44 of 204 (22%) from the historic National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics Human Genetics Program Familial Cancer Registry and 160 of 204 (78%) from various healthcare providers primarily in response to mailed recruitment letters. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Of the 204 women, ductal lavage was attempted on 171 women from 127 separate, unrelated families. Reasons for ductal lavage exclusion included physician cancellation (n = 13), being ineligible (n = 4), refusing (n = 5), and suspension of ductal lavage from the protocol in May 2006 (n = 11).

Duct Lavage Procedure

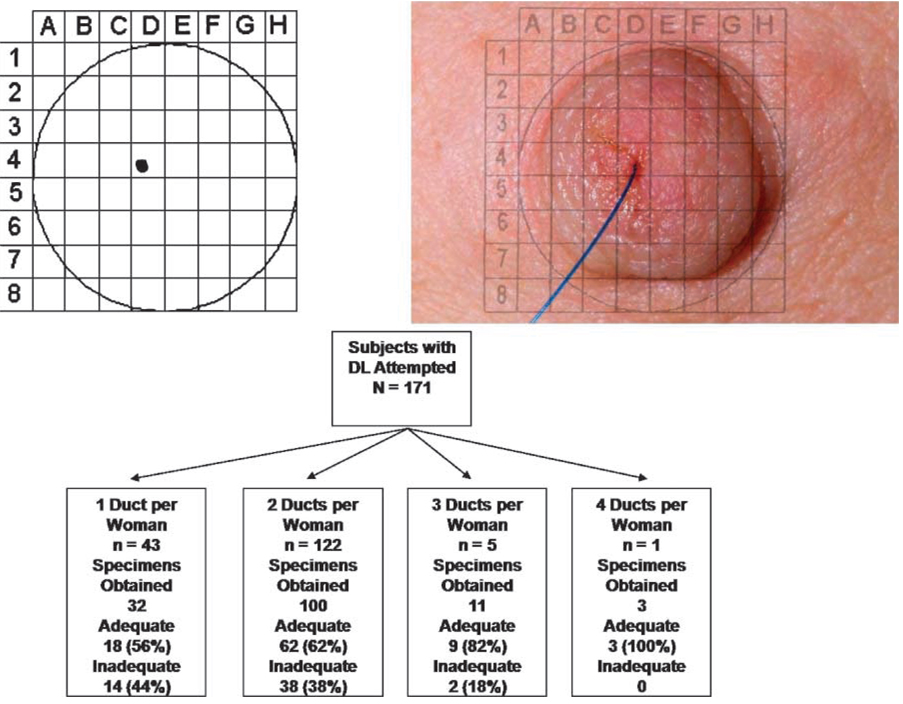

Participants’ nipples/areolae were anesthetized topically with EMLA cream (AstraZeneca) applied 60 min before the procedure. Warm packs were applied to the breasts and breast massage was done by the operators. Nuprep (B.O. Weaver and Co.) was used to dekeratinize the surface of the nipple before NAF collection. Nipple aspiration was done using a nipple aspirator (First-Cyte; Cytyc Health) to identify all fluid-yielding ducts. Regardless of NAF fluid status, attempts were made to cannulate visually identifiable ducts with a microdilator followed by catheterization (First-Cyte; Cytyc Health). If catheter insertion was successful, 1% lidocaine (3–5 mL) was infused into the duct, followed by ~20 mL sterile normal saline, in incremental 5 mL aliquots. After each 5 mL aliquot was infused, breast massage was done, and ductal fluid was collected via the lavage catheter. After catheter removal, the location of the lavaged duct was recorded by threading a blue suture into the ductal orifice and photographing the breast (Fig. 1). The position of the lavaged duct was recorded by mapping its location on a two-dimensional grid, which was entered into the participant’s permanent medical record. The ductal lavage procedure was done by three clinicians working together in pairs (J.T.L., adult nurse practitioner; R.G., medical oncologist; and L. Roderiquez, surgical oncologist) trained in the same methods as published by Dooley et al. (1).

Figure 1.

Ductal lavage photograph and specimen adequacy by number of ducts cannulated per woman.

Cytologic Examination

Ductal lavage fluid volume was measured, and a 20% aliquot was placed in a ThinPrep vial for cell count and cytologic analysis; the remaining specimen was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm. The supernatant and pellet were separated and frozen for future research studies. Two experienced cytologists (A.D.A. and A.C.F.) trained and mentored (in the early phase of this study) in interpretation of ductal lavage specimens (as described in the multicenter ductal lavage study; ref. 1) analyzed the ductal lavage cellular specimens prepared from the ThinPrep vials for adequacy, cytologic abnormalities, and cell counting following published guidelines (36). Cytology diagnostic categories used were similar to the 1997 consensus criteria for breast fine-needle aspiration biopsy samples reported by the National Cancer Institute (37). Cytopathologists employed a cell counting technique, which resulted in five diagnostic categories: inadequate cellular material for diagnosis (samples with <10 epithelial cells per sample), negative for malignant cells, atypia (mild, moderate and severe), suspicious for malignancy, and malignant as described previously (38). When any cytologic atypia was identified, a consultation with a breast surgeon (D.D.) was obtained. Repeat clinical and cytologic evaluation was done within 3 to 6 months after finding atypia.

Data Collection

Ductal lavage and clinical data were collected using study-specific questionnaires at the time of the annual visit and from history and physical examination forms. The ductal lavage cell counts were abstracted from the cytology report. All data were entered into an electronic database created using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft).

Postmenopausal status was defined as having had no menstrual cycles in the 12 months before enrollment or a history of bilateral oophorectomy. Premenopausal was defined as having menstrual cycles at regular intervals. One woman, status post-hysterectomy/unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, had premenopausal hormone levels.

Hormonal medication use status at the time of ductal lavage performance included the current use of oral contraceptive pills (OCP) or nonoral hormonal contraceptives (transdermal contraceptive patches and vaginal contraceptive rings), menopausal hormone therapy (MHT; combination estrogen, progesterone, estrogen-testosterone, or estrogen only), and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM), such as raloxifene or tamoxifen. Each type of hormonal medication was analyzed separately.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described in terms of mean/SD and median/range (for continuous variables). First, we examined associations with NAF; then, associations with ductal cell yield adequacy (defined as ≥10 cells per sample) were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon nonparametric test for continuous variables. Correlates of NAF and adequate ductal lavage cell yield were identified among all subjects from a multivariate logistic regression model, using backward selection procedure, retaining covariates with P ≤ 0.10. The same analysis was repeated among mutation carriers only. The following potential correlates were examined: age, menopausal status, race/ethnicity, BRCA1/2 mutations status, parity, body mass index, current use of MHT, OCP (or other hormonal contraceptives), SERM use, NAF status, and having a prior history of breast-feeding, breast cancer, ovarian surgery, breast surgery, or chemotherapy. We also identified correlates of ductal cell count using linear regression backward selection; the natural logarithmic transformation was applied to the predicted variable.

As an alternative to logistic regression models (which assume independence between subjects), we performed cluster analyses taking into account family membership by means of generalized estimating equations. Forty-three percent (73 of 171) of the study population had more than one member from the same family enrolled in the study, including 21 families of two, 4 families of three, 2 families of four, 1 family of five, and 1 family of six. Because we identified identical correlates of NAF and ductal lavage cell count adequacy, only results from logistic and linear regressions are presented thereafter. All statistical analyses were done using SAS statistical software (version 9.1; SAS Institute). All statistical tests were two-sided; P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Between June 1, 2002 and May 31, 2007, 204 women were enrolled in the study, of whom 171 underwent a ductal lavage attempt. Of these, 146 were BRCA mutation carriers (BRCA1 = 90 and BRCA2 = 56), 23 were mutation-negative, and 2 were untested. Twenty-one women had a prior personal history of breast cancer and 2 had a prior history of ovarian cancer. Twenty-five women had a prior breast surgery resulting in only one breast being evaluable. For the group of 171 who underwent a ductal lavage attempt, the average age at enrollment was 40.3 years (SD, 8.4; median, 40.7; range, 23–57), and average body mass index was 26.3 kg/m2 (SD, 5.6; median, 24.5; range, 15.6–50). Ninety-three (54.4%) women were premenopausal, 10 (6%) women were postmenopausal with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), and 68 (39.6%) women were postmenopausal without BSO. In this group of women, 18 (10.5%) were current users of MHT, 24 (14.0%) were current users of an OCP, and 13 (7.6%) were current users of a SERM. One hundred one (59%) of the 171 women who underwent a ductal lavage attempt were parous and 87 (50.9%) had previously breast-fed.

Correlates of NAF Production

Overall, NAF was obtained from 45 of 171 (26%) women. Mutation-negative women (Fisher P = 0.04) and older subjects (Wilcoxon P = 0.04) were more likely to yield NAF in univariate analysis (Table 1). There was no difference in yield between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (P = 0.31). None of the women (all BRCA1/2 mutation carriers) currently taking a SERM yielded NAF (0 of 13 versus 45 of 158) among nonusers (P = 0.02).

Table 1.

Correlates of obtaining NAF

| Predictor | NAF not obtained (n = 126) | NAF obtained (n = 45) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||

| Premenopausal | 71 (76.3) | 22 (23.7) | 0.49 |

| Postmenopausal | 55 (70.5) | 23 (29.5) | |

| BRCA1/2 mutation status, n (%) | |||

| Noncarrier (excluding 2 untested) | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 0.06 among all 3 categories |

| Carrier BRCA1 | 67 (74.4) | 23 (25.6) | 0.04 carriers vs noncarriers |

| Carrier BRCA2 | 46 (82.1) | 10 (17.9) | 0.31 among carriers only |

| Parity, n (%) | |||

| Nulliparous | 56 (80.0) | 14 (20.0) | 0.16 |

| Parous (≥1 births) | 70 (69 .3) | 31 (30.7) | |

| Breast-feeding, n (%) | |||

| Never breast-fed | 65 (77.4) | 19 (22.6) | 0.30 |

| Ever breast-fed | 61 (70.1) | 26 (29.9) | |

| Personal history of breast or ovarian cancer, n (%) | |||

| No | 106 (71.6) | 42 (28.4) | 0.14 |

| Yes | 20 (87.0) | 3 (13.0) | |

| Prior ovarian surgery, n (%) | |||

| Never, unilateral oophorectomy | 76 (73.8) | 27 (26.2) | 1.00 |

| Bilateral oophorectomy | 50 (73.5) | 18 (26.5) | |

| Prior breast surgery, n (%) | |||

| None | 105 (71.9) | 41 (28.1) | 0.32 |

| Mastectomy or lumpectomy | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Prior chemotherapy, n (%) | |||

| No | 111 (72.1) | 43 (27.9) | 0.24 |

| Yes | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Prior radiation, n (%) | |||

| No | 113 (72.0) | 44 (28.0) | 0.12 |

| Yes | 13 (92.9) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Current MHT use, n (%) | |||

| No | 114 (74.5) | 39 (25.5) | 0.57 |

| Yes | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | |

| Current OCP use, n (%) | |||

| No | 108 (85.7) | 39 (86.7) | 0.87 |

| Yes | 18 (14.3) | 6 (13.3) | |

| Current SERM use, n (%) | |||

| No | 113 (71.5) | 45 (28.5) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 13 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Age, mean (y) | 39.5 | 42.5 | 0.04 |

| Body mass index, mean (kg/m2) | 26.0 | 27.2 | 0.30 |

When multivariate methods were used to identify correlates of NAF, no prior personal history of breast cancer [odds ratio (OR), 5.2; P = 0.04] and being naturally postmenopausal compared with premenopausal (OR, 4.8; P = 0.03) increased the likelihood of obtaining NAF. Women who became postmenopausal after BSO were as likely to produce NAF as were the premenopausal women (OR, 1.3; P = 0.45).

Correlates of Ductal Lavage Results

Results per Duct

Of the 171 women in whom ductal lavage was undertaken, 44 had unilateral and 127 had bilateral ductal lavage attempted. In women who had only one breast attempted, 25 were ineligible to have a second breast examined due to prior breast surgery [lumpectomy (n = 17) and mastectomy or other breast surgery (reconstruction; n = 8)] and 19 were not attempted due to patient refusal, time constraints, or clinician decision. The ductal lavage procedure was attempted on 306 successfully cannulated ducts and produced 145 specimens (47% of all ducts attempted), of which only 92 (63% of all samples and 30% of all ducts) were adequate for cytologic diagnosis.

Results per Subject

Ductal lavage was attempted on 171 women and produced specimens from 107 women, 70 of whom had adequate cell yield (65% of women yielding a sample and 41% of all women attempting ductal lavage). Women in whom multiple ducts were cannulated were more likely to yield one or more adequate ductal lavage specimens (Fig. 1). The mean number of ducts cannulated per women was 0.86 (SD, 0.80; median, 1; range, 0–3), and the mean number of ducts with adequate ductal cell counts >10 per woman was 0.54 (SD, 0.75; median, 0; range, 0–3).

Cell Counts per Duct

The mean ductal cell yield from the 70 women with samples adequate for cytologic review was 12,361 (SD, 25,076), with a median of 1,885 (range, 20–148,564). The ductal cell count obtained from NAF-yielding ducts (mean, 7,934; SD, 18,506; median, 1,254; range, 20–72,620) and non-NAF-yielding ducts (mean, 15,142; SD, 28,293; median, 3,300; range, 100–148,564) were not significantly different (Wilcoxon P = 0.20).

Correlates of Cell Count Adequacy

Univariate analyses (Table 2) identified the following factors as positively associated with obtaining adequate cell counts: being mutation-negative, having had at least one child, a prior history of breast-feeding, obtaining NAF, and no current SERM use.

Table 2.

Correlates of obtaining adequate ductal lavage cell count (n = 171)

| Predictor | Inadequate sample (n = 101) | Adequate sample (n = 70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||

| Premenopausal | 49 (52.7) | 44 (47.3) | 0.064 |

| Postmenopausal | 52 (66.7) | 26 (33.3) | |

| BRCA1/2 mutation status, n (%) | |||

| Noncarrier (2 untested excluded) | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | 0.048 among all 3 categories |

| Carrier BRCA1 | 50 (55.6) | 40 (44.4) | 0.11 carriers vs noncarriers |

| Carrier BRCA2 | 40 (71.4) | 16 (28.6) | 0.080 between BRCA1/2 |

| Parity, n (%) | |||

| Nulliparous | 48 (68.6) | 22 (31.4) | 0.041 |

| Parous (≥1 births) | 53 (52.5) | 48 (47.5) | |

| Breast-feeding, n (%) | |||

| Never breast-fed | 59 (70.2) | 25 (29.8) | 0.005 |

| Ever breast-fed | 42 (48.3) | 45 (51.7) | |

| NAF obtained, n (%) | |||

| No | 83 (65.9) | 43 (34.1) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 18 (40.0) | 27 (60.0) | |

| Prior breast cancer, n (%) | |||

| No | 85 (56.7) | 65 (43.3) | 0.10 |

| Yes | 16 (76.2) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Prior ovarian surgery, n (%) | |||

| Never or unilateral oophorectomy | 57 (55.3) | 46 (44.7) | 0.27 |

| Bilateral oophorectomy | 44 (64.7) | 24 (35.3) | |

| Prior breast surgery, n (%) | |||

| None | 82 (56.2) | 64 (43.8) | 0.079 |

| Mastectomy or lumpectomy | 19 (76.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Prior chemotherapy, n (%) | |||

| No | 88 (57.1) | 66 (42.9) | 0.19 |

| Yes | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Prior radiation, n (%) | |||

| No | 90 (57.3) | 67 (42.7) | 0.16 |

| Yes | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Current MHT use, n (%) | |||

| No | 87 (56.9) | 66 (43.1) | 0.13 |

| Yes | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Current OCP use, n (%) | |||

| No | 88 (59.9) | 59 (40.1) | 0.66 |

| Yes | 13 (54.2) | 11 (45.8) | |

| Current SERM use, n (%) | |||

| No | 89 (56.3) | 69 (43.7) | 0.016 |

| Yes | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Age (y), mean | 40.6 | 39.7 | 0.39 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean | 26.1 | 26.6 | 0.88 |

In multivariate analyses (Table 3A), a prior history of breast-feeding (OR, 3.4; P = 0.001), whether NAF was obtained before ductal lavage (OR, 3.2; P = 0.003), and being premenopausal as opposed to postmenopausal (OR, 3.0; P = 0.003) were associated with a greater likelihood of obtaining an adequate ductal lavage sample in all patients combined. Whether women became postmenopausal naturally or after BSO did not modify the likelihood of ductal lavage cell count adequacy.

Table 3.

Multivariate correlates of adequate ductal lavage cell count

| Predictor retained from univariate model |

OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| (A) All subjects undergoing ductal lavage (n = 171) | ||

| Menopausal status (pre vs post) | 3.0 (1.4–6.1) | 0.003 |

| Breast-feeding (ever vs never) | 3.4 (1.7–7.0) | 0.001 |

| NAF obtained (yes vs no) | 3.2 (1.5–6.7) | 0.003 |

| (B) BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (n = 146) | ||

| Breast-feeding (ever vs never) | 2.5 (1.2–5.2) | 0.01 |

| NAF obtained (yes vs no) | 3.0 (1.3–7.0) | 0.01 |

| No current MHT use (no vs yes) | 3.1 (0.9–10.8) | 0.07 |

| No SERM use (no vs yes) | 7.1 (0.9–58.0) | 0.07 |

Multivariate methods were then used to examine the same variables and the likelihood of obtaining an adequate ductal lavage sample in the women who were known BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (n = 146; Table 3B). Having a prior history of breast-feeding (OR, 2.5; P = 0.01) and whether NAF was obtained before ductal lavage (OR, 3.0; P = 0.01) increased the likelihood of obtaining an adequate ductal lavage sample; menopausal status was not a significant correlate in this population.

We verified that correlates of NAF and ductal lavage cell count adequacy remained unchanged after we took into account the clustering of subjects resulting from family membership (data not presented).

Finally, linear regression was used to model the correlates of higher mean cell count (n = 70) with all the variables considered in the multiple logistic regression models. Only a prior history of BSO was significantly associated with lower mean cell counts (mean, 6,343 in BSO subjects versus 15,502 in non-BSO subjects; P = 0.04).

Atypia Findings on Cytology

Of the 92 adequate samples examined, mild atypia was detected in 5 (5.4%), each representing a different subject. The cell counts for samples with atypia ranged from 500 to 43,326. Three of the specimens with atypia were from non-NAF-bearing ducts, and three were obtained from BRCA1- or BRCA2-positive women. All 5 women were evaluated by a breast surgeon and underwent repeat ductal lavage (n = 2), ductal endoscopy (n = 2), or breast imaging (n = 1) within 6 months. None of the women with atypia had a prior personal history of breast cancer nor have any subsequently developed breast cancer during an average of 48 months of prospective follow-up.

Prevalent Breast Cancer

Before Study Enrollment

Twenty-one women had a personal history of breast cancer, which preceded their study enrollment; an evaluable ductal lavage sample was obtained from the contralateral breast in 9 (43%) women. None had cytologic atypia on their baseline ductal lavage sample. Ductal lavage specimens were not obtained from the remaining 12 women: 2 patients refused and 10 were unsuccessful cannulation.

As a Consequence of the Baseline Examination

Six study participants (all mutation carriers) were diagnosed with a breast cancer and one study participant was diagnosed with lobular neoplasia as a result of the baseline evaluation (Table 4). Ductal lavage was attempted in all seven women, but successful duct cannulation and specimen collection was achieved in only one, whose cytology was normal.

Table 4.

Characteristics of breast cancers detected by baseline screening exam

| Case | Age at diagnosis |

Morphology | Grade | Palpable mass |

Prognostic markers |

Detection method |

Ductal lavage cell count |

Vital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | Infiltrating ductal and lobular carcinoma | Grade III, poorly differentiated | No | ER+ PR+ HER+3, FISH 8.8 | Mammography, MRI | 0 | Alive |

| 2 | 29 | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | Grade or cell type not determined, not stated, or N/A | No | ER+ PR+ | Mammography | 0 | Alive |

| 3 | 37 | Lobular neoplasia | N/A | No | N/A | MRI | 0 | Alive |

| 4 | 48 | Lobular carcinoma | Grade or cell type not determined | No | ER+ PR- HER-2 IHC+2 | Mammography | 6,039 | Alive |

| 5 | 51 | Intraductal carcinoma, noninfiltrating | Grade IV, undifferentiated, anaplastic | No | ER+ PR+ HER+3, FISH 8.8 | MRI | 0 | Alive |

| 6 | 37 | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | Grade IV, undifferentiated, anaplastic | Yes | Unavailable | Mammography, MRI | 0 | Alive |

| 7 | 41 | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | Grade III, poorly differentiated | No | ER- PR- HER-2 IHC+2 | Mammography, MRI | 0 | Alive |

Discussion

Our NAF and ductal lavage experience among women from BRCA mutation-positive families represents the largest analyzed series to date, with 874 person-years of observation. In the current study, we identified significant positive multivariate correlations between ductal lavage cell count adequacy and premenopausal status, having breast-fed, and the presence of NAF for all women combined. When evaluating mutation carriers separately, only having breast-fed and the presence of NAF were positively associated with cell count adequacy. Prior BSO was associated with significantly lower cell counts. We also identified univariate correlates of successfully obtaining NAF, which included older age (≥40 years), mutation-negative status, and absence of SERM exposure. In multivariate analysis, being postmenopausal, when compared with being premenopausal, was the only significant predictor of success obtaining NAF. Being postmenopausal and having prior salpingo-oophorectomy lowered the odds of having NAF when compared with postmenopausal women with intact ovaries (OR, 1.3 versus 4.8).

Compared with previous reports of ductal lavage in women with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, our findings differ in several important aspects. First, ours is the largest series of ductal lavage results in mutation-positive women, which should produce more stable estimates regarding associations of interest. Overall, the women in our study were ~3 years younger (40 versus 43 in two prior studies; refs. 13, 14) than previous reports. They were less likely to have had breast and/or ovarian cancer (14% versus 40% and 35%; refs. 13, 14) and more likely to be nulliparous (41% versus 15% and 29%; refs. 13, 14). Our postmenopausal subjects were somewhat more likely to have undergone prior BSO (87% versus 84% and 70%; refs. 13, 14). The number of women who yielded NAF shows the variability in the growing NAF experience (26% versus 13%, 52%, and 60%) as part of the ductal lavage procedure (8, 13, 14) in women with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

Our univariate analysis confirmed earlier findings that NAF expression correlates positively with cellular yield on ductal lavage (13, 14) and further identified a prior history of breast-feeding, having at least one live birth, and no current use of a SERM as positively associated with obtaining an adequate ductal lavage cell count.

Of note, SERMs were used only by mutation carriers in our series (13 of 146); none of the noncarriers (0 of 23) were current or past SERM users. Only one mutation-negative woman was currently using MHT; all remaining 17 MHT users were carriers. Women not using either a SERM or MHT were more likely (OR, 7.09; P = 0.07 and OR, 3.14; P = 0.07, respectively) to have an adequate cell yield, although these findings were of borderline significance. This finding in relation to SERM use is consistent with the known antiestrogenic effect of SERMs on breast ductal epithelial proliferation. Women taking MHT in this group represented women who had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy to lower the risk of ovarian cancer. This suggests that the loss of estrogen’s proliferative effect on the breast is not reversed by the post-risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy administration of MHT.

Like other groups, we did detect cytologic atypia in ductal lavage fluid from both NAF-yielding and non-NAF-yielding ducts; however, our atypia rates were much lower (3% versus 28% and 21%) than those previously reported in mutation carriers (13, 14). Interobserver variability in cytology scoring can affect the reported prevalence of ductal lavage atypia. To reduce the interobserver variability in our series, all specimens were reviewed independently by two cytopathologists (A.D.A. and A.C.F.), who were both trained and mentored in evaluating ductal lavage specimens. Cytologic atypia in ductal lavage samples was not associated with any significant physical examination, mammography, or MRI abnormalities in any of our patients either at the time of ductal lavage or during up to 4 years of prospective follow-up. This experience is different from that of a prior report, which identified MRI “abnormalities” in six of seven breasts with ductal lavage-related cytologic atypia (34). Three of those seven women were BRCA mutation carriers, none of whom had documented neoplasia on follow-up of their imaging findings (34).

With respect to ductal lavage sample adequacy, despite obtaining 145 specimens for cytologic review (145 of 306 ducts attempted), only 92 specimens contained sufficient numbers of exfoliated breast epithelial cells to be considered adequate (31%) for cytologic review. This finding is similar to a recently reported 31% rate of adequate cell counts for cytologic review obtained by ductal lavage in 86 women at “high risk” of breast cancer when compared with 100% adequate cell counts obtained by random periareolar fine-needle aspiration (5). Several other groups have reported their experience with reduced NAF retrieval rates (8), low ductal lavage cell yields (6, 8, 9, 11), and low reproducibility of cytologic findings and participants’ return rates (6, 9, 11) and have concluded that, among women at high risk of breast cancer, ductal lavage is of limited clinical value for repeated sampling of the breast epithelium.

Other groups have reported higher rates of adequate cell counts in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (87% and 61% in 56 and 52 mutation carriers, respectively; refs. 13, 14). The differences in the characteristics of the group of women in the current study related to age, parity, and prior personal history of breast and ovarian cancer may explain these differences. The patients’ extended 2-day visit may have had an unexpected detrimental affect on the NAF and ductal lavage procedures. NAF and ductal lavage were attempted only once per annual clinical visit and were the last procedures of a 2-day breast and ovarian cancer screening visit. It is possible that, if time had permitted multiple attempts at NAF, our NAF and ductal lavage cellularity rates could have increased. It is also possible that patient fatigue or mild dehydration may have lowered the overall success rate. It is also possible that our sample size, which is nearly four times that of prior reports, has permitted us to make estimates of various NAF and ductal lavage parameters that are more precise and stable than those derived from smaller studies.

Strengths of our analysis include the size and geographical diversity (36 of the 50 states, one U.S. Territory, Bermuda, and Canada) of the study population, the large proportion of subjects who are BRCA mutation-positive, and its prospective design. In addition, the majority of study participants were unrelated to one another, unlike the more common scenario in tertiary care high-risk clinics, in which multiple members of the same family are more likely to be seen. Our study subjects represented 127 separate, unrelated families. Finally, a unique feature of this study was the deliberate enrollment of several mutation-negative women, which was intended to serve as a comparison group.

Based on the very high lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers would seem to be ideal candidates for ductal lavage. However, in our experience, 74% (126 of 171) of potential candidates did not yield NAF, 37% (64 of 171) could not have a duct cannulated, and 59% (101 of 171) did not yield a cytologically evaluable sample. Thus, we were able to acquire a cytologically evaluable sample in only 41% of all subjects considered for ductal lavage. Our experience suggests that ductal lavage is not likely to play a central clinical role in breast cancer screening among high-risk women, because women find it painful and are reluctant to undergo multiple ductal lavage examinations over time (11) and because the procedure fails to yield large enough numbers of exfoliated epithelial cells to permit reliable cytologic diagnosis or to support cell-based translational research activities. Systematic evaluation of alternative tissue acquisition strategies in large numbers of carefully studied BRCA mutation carriers remains a high priority research focus.

Acknowledgment

We thank Luz Roderiquez, M.D., and Ruth Foelber, R.N., for clinical support, Nicole Dupree, Beth Mittl, Jason Hu, and Usha Singh for help in data preparation, Hormuzd Kakti, Ph.D., for help with the generalized estimating equations analysis, and especially the women who contributed time and efforts to support this study.

Grant support: Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Cancer Institute and Westat support services contracts NO2-CP-11019-50 and N02-CP-65504.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Dooley WC, Ljung BM, Veronesi U, et al. Ductal lavage for detection of cellular atypia in women at high-risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1624–1632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.21.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrensch MR, Petrakis NL, King EB, et al. Breast cancer incidence in women with abnormal cytology in nipple aspirates of breast fluid. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:130–141. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabian CF, Kimler BF, Zelles CM, et al. Short-term breast cancer prediction by random periareolar fine-needle aspiration cytology and the Gail risk model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.15.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buehring GC, Letscher A, McGirr KM, et al. Presence of epithelial cells in nipple aspirate fluid is associated with subsequent breast cancer: a 25-year prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;29:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arun B, Valero V, Logan C, et al. Comparison of ductal lavage and random periareolar fine needle aspiration as tissue acquisition methods in early breast cancer prevention trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4943–4948. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carruthers DC, Chapleskie LA, Flynn MB, Frazier TG. The use of ductal lavage as a screening tool in women at high risk for developing breast carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2007;194:463–466. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson-Maddux A, Ashfaq R, Cler L, et al. Reproducibility of cytologic atypia in repeat nipple duct lavage. Cancer. 2005;103:1129–1136. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins SA, Matloff ET, Rimm DL, et al. Patterns of reduced nipple aspirate fluid production and ductal lavage cellularity in women at high risk for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;7:R1017–R1022. doi: 10.1186/bcr1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patil DB, Lankes HA, Nayar R, et al. Reproducibility of ductal lavage cytology and cellularity over a six month interval in high risk women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9861-8. Published online 2007 Dec 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P, Klemp JR, Simensen M, et al. Failure of high risk women to produce nipple aspirate does not exclude detection of cytologic atypia in random periareolar needle aspiration specimens. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;87:59–64. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000041582.11586.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visvanathan K, Santor D, Ali SZ, et al. The reliability of nipple aspirate and ductal lavage in women at increase risk for breast cancer—a potential tool for breast cancer risk assessment and biomarker evaluation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:950–955. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zalles CM, Kimler BF, Simonsen M, et al. Comparison of cytomorphology in specimens obtained by random periareolar fine needle aspiration and ductal lavage from women at high risk for development of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;97:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurian AW, Mills MA, Jaffee M, et al. Ductal lavage of fluid-yielding and non-fluid-yielding ducts in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and other women at high inherited breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1082–1089. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell G, Antill YC, Murray W, et al. Nipple aspiration and ductal lavage in women with a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;7:1122–1131. doi: 10.1186/bcr1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for White females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Euhus DM, Bu D, Ashfaq R, et al. Atypia and DNA methylation in nipple duct lavage in relation to predicted breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1812–1821. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabian CJ. Is there a future for ductal lavage? Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4655–4656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathanson DL, Wooster R, Weber BL. Breast cancer genetics: what we know and what we need. Nat Med. 2001;7:552–556. doi: 10.1038/87876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peto J. Breast cancer susceptibility—a new look at an old model. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:411–412. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1123. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King MC, Marks JH, Mandell JB, et al. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643–646. doi: 10.1126/science.1088759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner TM, Moslinger R, Langbauer G, et al. Attitude towards prophylactic surgery and effects of genetic counseling in families with BRCA mutations. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1249–1253. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meijers-Heijboer H, Brekelmans CT, Menke-Pluymers M, et al. Use of genetic testing and prophylactic mastectomy and oophorectomy in women with breast or ovarian cancer from families with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1675–1681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouchard L, Blancquaert I, Eisinger F, et al. Prevention and genetic testing for breast cancer: variations in medical decisions. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:77–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domcheck SM, Weber BL. Clinical management of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Oncogene. 2006;25:5825–5831. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE study group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1055–1062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl Med. 2002;346:1609–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rebbeck TR, Henry TL, Neuhausen SL, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616–1622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer J, Velazquez I, Chen BS, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy reduces breast cancer penetrance during prospective, long-term follow-up of BRCA 1 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8629–8635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metcalf K, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, et al. Contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2328–2335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narod SA, Brunet JS, Ghadirian P, et al. Tamoxifen and risk of contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: a case-control study. Lancet. 2000;356:1876–1881. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.King MC, Wieand S, Hale K, et al. Tamoxifen and breast cancer incidence among women with inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP-P1) Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2251–2256. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartman AF, Daniel BL, Kurian AW, et al. Breast magnetic resonance image screening and ductal lavage in women at high genetic risk for breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:479–489. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clinical Genetics Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics NCI, NIH, DHHS. [Accessed 2007 Jul];The breast imaging study. Available from: http://breastimaging.cancer.gov/

- 36.Abati A, Greene MH, Filie AC, et al. Quantification of the cellular components of breast ductal lavage samples. Diagn Ctyopathol. 2006;34:78–81. doi: 10.1002/dc.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NIH Consensus Conference. The uniform approach to breast fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Am J Surg. 1997;174:371–385. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danforth DN, Abati A, Filie A, et al. Combined breast ductal lavage and ductal endoscopy for evaluation of the high-risk breast: a feasibility study. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:555–564. doi: 10.1002/jso.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]