Abstract

Objective

To describe red blood cell (RBC) transfusion practices and evaluate the association between patient-related factors and pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration in acute lung injury (ALI).

Design

Secondary analysis of prospectively collected data

Setting

9 intensive care units (ICUs) in 3 teaching hospitals in Baltimore, MD

Patients

249 consecutive, mechanically ventilated ALI patients

Interventions

None

Measurements and Main Results

Simple and multiple linear regression analyses were used to evaluate the association between the nadir hemoglobin concentration on the day of initial RBC transfusion and 20 patient-level demographic, clinical and ICU treatment factors as well as ICU type. Of 249 ALI patients, 47% received a RBC transfusion in the ICU without evidence of active hemorrhage or acute cardiac ischemia. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) nadir hemoglobin on the day of first transfusion was 7.7 (1.1) g/dL with 67%, 36%, 15%, and 5% of patients transfused at >7, >8, >9, and >10g/dL, respectively. Transfused patients received a mean (SD) of 5 (6) RBC units from ALI diagnosis to ICU discharge. Pre-hospital use of iron or erythropoietin and platelet transfusion in the ICU were independently associated with lower pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentrations. No patient factors were associated with higher hemoglobin concentrations. Admission to a surgical (vs. medical) ICU was associated with a 0.6 g/dL (95% CI: 0.1, 1.1 g/dL) higher pre-transfusion hemoglobin.

Conclusions

ALI patients commonly receive RBC transfusions in the ICU. The pre-transfusion hemoglobin observed in our study was lower than earlier studies, but a restrictive strategy was not universally adopted. Patient factors do not explain the gap between clinical trial evidence and routine transfusion practices. Future studies should further explore ICU- and physician-related factors as a source of variability in transfusion practice.

Keywords: blood transfusion, erythrocyte indices, respiratory distress syndrome, adult, intensive care units, outcome and process assessment (health care)

Introduction

Over the last decade, clinical research has demonstrated that a restrictive strategy for the transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) should be used for critically ill patients who are not hemorrhaging or experiencing active cardiac ischemia. Specifically, a large multi-center randomized study, the Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care (TRICC) trial, found that transfusing for a hemoglobin <7g/dL was at least as effective as a liberal strategy (transfusing for a hemoglobin <10g/dL) when considering patient mortality.(1) Moreover, RBC transfusion is associated with increased complications including nosocomial infections(2–6) and acute lung injury.(7–11) Despite this research evidence, 3 large population-based observational studies, conducted 1 – 3 years after the TRICC trial publication, demonstrated that mean transfusion thresholds (8.2 – 8.6 g/dL) remain above the level recommended by this trial.(12–14)

In patients with acute lung injury (ALI), a restrictive transfusion strategy may be especially important. Liberal RBC transfusion does not improve ventilator-free days for mechanically ventilated patients.(15) Furthermore, each RBC unit transfused is independently associated with a 6 – 10% greater odds of death.(16, 17) Understanding transfusion practices in ALI patients and the factors associated with variations in transfusion thresholds may help in developing strategies to improve evidence-based practice. Consequently, we sought to describe recent RBC transfusion practices in a cohort of ALI patients and to evaluate what factors were associated with the pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration in those patients receiving a transfusion in the intensive care unit (ICU) after ALI onset.

Material and Methods

Study Setting

Nine ICUs (3 medical, 4 surgical, and 2 trauma) at 3 teaching hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland provided data for this analysis. All MICUs in the study have a dedicated ICU team solely responsible for patient care. All SICU study sites utilize a co-management model with all patients being managed by the dedicated ICU team as well as the patient’s primary surgical team. RBC transfusions in the study site ICUs are prescribed by a variety of clinicians (e.g., attending, fellow and resident physicians, and nurse practitioners). None of the ICUs have a written protocol for transfusion practices or routinely document the indication for transfusion when ordered.

Study Participants

Consecutive mechanically ventilated patients diagnosed with ALI using American-European Consensus Conference criteria(18) were enrolled from October 2004 to July 2006.(19) Exclusion criteria for the cohort study included: (1) pre-existing ALI for >24 hours before transfer to a study site ICU; (2) >5 days of mechanical ventilation prior to eligibility; (3) a limitation in care (e.g., no vasopressors) at eligibility; or (4) a pre-existing condition with a life expectancy <6 months. A convenience sample of 249 consecutive patients enrolled in the ongoing cohort study was used for this secondary data analysis. Consistent with the TRICC trial eligibility criteria, we excluded patients from the study cohort who had active blood loss (defined as a diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding or hemorrhagic shock at ICU admission, or transfusion of >3 RBC units on the day of first transfusion) or had acute cardiac disease (defined as a diagnosis of acute myocardial ischemia at ICU admission or an elevated troponin on the day of first transfusion).(1)

Outcome

The primary outcome for this study was the nadir hemoglobin concentration (g/dL) on the day of first RBC transfusion in the ICU after ALI diagnosis.

Exposure

Based on published literature and expert opinion, we prospectively collected data on patient characteristics potentially associated with RBC transfusion.(1, 12, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21) In addition to demographic data (age, sex, and race), 11 patient clinical characteristics were measured: comorbid conditions (Charlson comorbidity index(22) and cardiac disease), routine pre-hospital use of medications which may influence hematopoiesis (iron, erythropoietin, folate, and vitamin B12), primary ICU admitting diagnosis, severity of illness at ICU admission (Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation [APACHE] II score(23)), ALI risk factor, severity of lung injury at ALI onset (Lung Injury Score [LIS], calculated based on chest radiograph, hypoxemia, and positive end expiratory pressure [PEEP] data(24)), and organ dysfunction on the day of transfusion (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA]).(25)

Additionally, 6 exposure variables related to a patient’s ICU course were evaluated: ICU admission source (emergency department or ward at the study site hospital, or transfer from an outside hospital) and potentially relevant ICU interventions occurring from ALI onset through the day of first RBC transfusion (platelet transfusion, iron administration, erythropoietin administration, continuous hemodialysis, and intermittent hemodialysis). Finally, ICU type (medical or surgical) was evaluated as an organizational factor potentially associated with transfusion practices.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported using mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous data and proportions for categorical data. Continuous data and proportions were compared using the Student’s t-test and chi-square test, respectively. Exposures were modeled based upon published literature. When such information was not available, we examined a scatterplot of the exposure and outcome variable using a locally weighted linear regression (LOWESS) to determine appropriate modeling of the exposure.(26)

Simple linear regression was used to evaluate the association of each exposure variable with the nadir hemoglobin the day of RBC transfusion. Exposures with an association of p ≤0.15 were included in a subsequent multiple linear regression model. This analysis adjusted for potential clustering of outcome data within each ICU (i.e. ICU-specific effect on transfusion practices) using a fixed effects model with robust variance estimation. Variance inflation factors were used to confirm that collinearity was not present among exposure variables in the final model. Diagnostic plots (e.g., residual vs. fitted values) were used to confirm that the final model did not violate any assumptions required for linear regression.

All analyses were performed using STATA version 10.0 (College Station, TX). A 2-sided p-value <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The Institutional Review Boards at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and all participating sites approved the study.

Results

Patient Characteristics

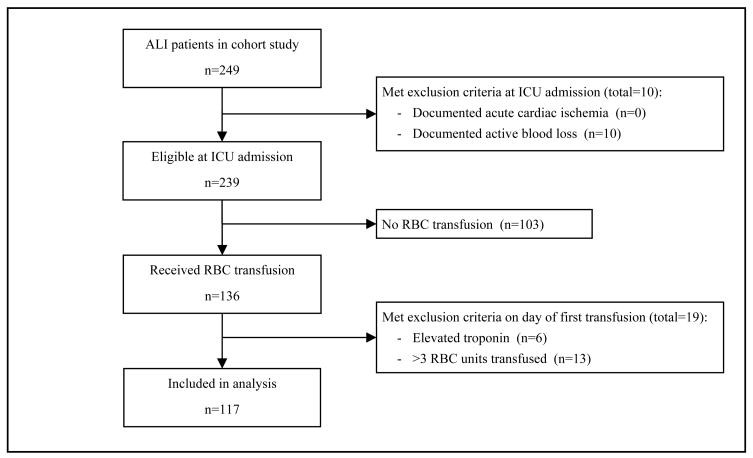

Of the 249 patients enrolled in the cohort study, 117 (47%) received a RBC transfusion without evidence of active blood loss or acute cardiac disease (Figure 1). Only 1 such patient received care in a trauma ICU and, for the purposes of this analysis, was categorized with surgical ICU patients at the same hospital. The characteristics of these transfused patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 54 (16) years and comorbid cardiac disease was documented in 18% of patients. Pulmonary diagnoses (including pneumonia) accounted for 57% of ICU admitting diagnoses. ALI was attributed to pulmonary risk factors (e.g., aspiration and pneumonia) for 48% of patients. Most patients (79%) were admitted to a medical ICU.

Figure 1.

Enrollment of study participants

ALI, acute lung injury; RBC, red blood cell

Table 1.

Characteristics of 117 patients with acute lung injury receiving red blood cell transfusion in the ICU

| Exposure Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Patient Demographic Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 54 (16) |

| Male, % | 52 |

| Caucasian, % | 51 |

| Patient Clinical Characteristics | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 2 (2) |

| Comorbid cardiac disease, % | 18 |

| Routine iron use prior to hospitalization, % | 8 |

| Routine erythropoietin use prior to hospitalization, % | 5 |

| Routine folate use prior to hospitalization, % | 7 |

| Routine vitamin B12 use prior to hospitalization, % | 1 |

| Primary ICU admitting diagnosis, % | |

| Pulmonary (including pneumonia) | 57 |

| Non-pulmonary sepsis and infectious disease | 15 |

| Gastrointestinal | 9 |

| Cardiovascular | 6 |

| Other | 12 |

| APACHE II at ICU admission, mean (SD) | 25 (8) |

| Pulmonary ALI risk factor, % | 48 |

| Lung Injury Score at ALI onset, mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.7) |

| SOFA score on day of first transfusion, mean (SD) | 9.3 (3.9) |

| Patient ICU Course Characteristics | |

| ICU admission source, % | |

| Emergency department | 39 |

| Ward | 51 |

| Outside hospital | 10 |

| Platelet transfusiona, % | 21 |

| Iron administrationa, % | 10 |

| Erythropoietin administrationa, % | 9 |

| Continuous hemodialysisa, % | 20 |

| Intermittent hemodialysisa, % | 9 |

| ICU type, % | |

| Medical | 79 |

| Surgical | 21 |

ICU, intensive care unit; SD, standard deviation; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Proportion of patients receiving the ICU intervention at any time from the day of ALI onset through the day of first red blood cell transfusion

Transfusion Practices

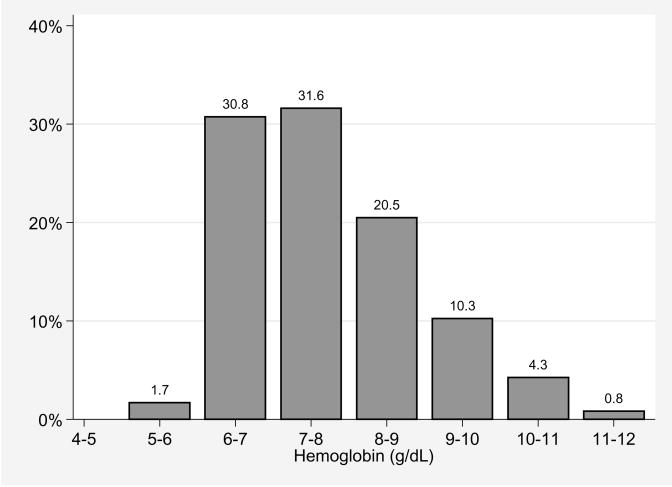

The mean (SD) nadir hemoglobin on the day of first transfusion was 7.7 (1.1) g/dL, with 67%, 36%, 15%, and 5% of patients transfused for a nadir hemoglobin ≥7, ≥8, ≥9, and ≥10 g/dL, respectively (Figure 2). The mean (SD) time to first transfusion after ALI diagnosis was 3 (5) days with 41%, 48%, and 11%, of patients receiving 1, 2, and 3 RBC units on this day, respectively. From ALI diagnosis to ICU discharge, each patient received an average (SD) of 5 (6) RBC units.

Figure 2.

Distribution of nadir hemoglobin on the day of first RBC transfusion for 117 acute lung injury patients

RBC, red blood cell

Factors Associated with Pre-transfusion Hemoglobin Concentration

Nine exposure variables were associated (p ≤0.15) with the mean nadir hemoglobin concentration on the day of first RBC transfusion using simple linear regression (Table 2). Higher mean nadir hemoglobin concentrations were associated with age, Caucasian race, a gastrointestinal primary ICU admitting diagnosis, and admission to a surgical (versus medical) ICU. Five factors were associated with a lower mean nadir hemoglobin concentration: a higher Charlson comorbidity index, routine use of iron prior to hospital admission, routine use of erythropoietin prior to hospital admission, greater Lung Injury Score, and platelet transfusion in the ICU.

Table 2.

Crude association of individual patient characteristics and ICU type with pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration

| Exposure Variable | Mean Change (95% CI) in Nadir Hemoglobina, g/dL | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age | 0.01 (0.0, 0.03) | 0.06 |

| Male | −0.1 (−0.6, 0.3) | 0.49 |

| Caucasian | 0.3 (−0.1, 0.7) | 0.14 |

| Patient Clinical Characteristics | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.0) | 0.03 |

| Comorbid cardiac disease | 0.3 (−0.2, 0.8) | 0.28 |

| Routine iron use prior to hospitalization | −0.6 (−1.4, 0.2) | 0.15 |

| Routine erythropoietin use prior to hospitalization | −1.0 (−1.9, −0.1) | 0.03 |

| Routine folate use prior to hospitalization | −0.3 (−1.1, 0.5) | 0.48 |

| Routine vitamin B12 use prior to hospitalization | 0.5 (−1.8, 2.8) | 0.66 |

| Primary ICU admitting diagnosis | ||

| Pulmonary (including pneumonia) | Reference | - |

| Non-pulmonary sepsis and infectious disease | 0.005 (−0.6, 0.6) | 0.99 |

| Gastrointestinal | 0.8 (−0.0, 1.5) | 0.04 |

| Cardiovascular | 0.5 (−0.4, 1.4) | 0.25 |

| Other | 0.05 (−0.6, 0.7) | 0.87 |

| APACHE II at ICU admission | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.04) | 0.29 |

| Pulmonary ALI risk factor | −0.1 (−0.5, 0.4) | 0.79 |

| Lung Injury Score at ALI onset | −0.2 (−0.5, 0.05) | 0.10 |

| SOFA score on day of first transfusion | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.09) | 0.23 |

| Patient ICU Course Characteristics | ||

| ICU admission source | ||

| Emergency department | Reference | - |

| Ward | 0.01 (−0.4, 0.5) | 0.97 |

| Outside hospital | −0.3 (−1.0, 0.5) | 0.45 |

| Platelet transfusionb | −0.6 (−1.1, −0.1) | 0.02 |

| Iron administrationb | −0.02 (−0.7, 0.7) | 0.96 |

| Erythropoietin administrationb | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.6) | 0.61 |

| Continuous hemodialysisb | 0.01 (−0.5, 0.5) | 0.98 |

| Intermittent hemodialysisb | −0.1 (−0.8, 0.6) | 0.78 |

| Surgical (vs. Medical) ICU | 0.8 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.002 |

ICU, intensive care unit; CI, confidence interval; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ALI, acute lung injury; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; SD, standard deviation

Mean change in nadir hemoglobin concentration on day of first red blood cell transfusion associated with each 1 unit increase in continuous exposure variables (e.g., age) or each categorical exposure variable (e.g., comorbid cardiac disease) versus its reference category as calculated using simple linear regression.

Proportion of patients receiving the ICU intervention at any time from the day of ALI onset through the day of first red blood cell transfusion.

The 9 variables crudely associated with pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration were evaluated in the multiple linear regression model (Table 3). This analysis demonstrated that three patient-related factors were independently associated with lower pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentrations. Routine iron use prior to hospitalization, routine erythropoietin use prior to hospitalization, and platelet transfusion in the ICU were respectively associated with 0.5 g/dL (95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.1 to 1.0 g/dL), 0.8 g/dL (CI: 0.3 to 1.4 g/dL), and 0.5 (CI: 0.005 to 0.9 g/dL) lower pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration. No patient-related factors were significantly associated with a higher hemoglobin concentration. The type of ICU was a significant factor, with patients admitted to a surgical ICU being transfused at a mean nadir hemoglobin concentration 0.6 g/dL (CI: 0.1 to 1.1 g/dL) higher than patients admitted to a medical ICU.

Table 3.

Adjusted association of individual patient characteristics and ICU type with pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration.

| Exposure Variablea | Mean Change (95% CI) in Nadir Hemoglobinb, g/dL | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Demographic Characteristic | ||

| Age | 0.002 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.74 |

| Caucasian | −0.06 (−0.4, 0.3) | 0.76 |

| Patient Clinical Characteristics | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | −0.05 (−0.1, 0.0) | 0.20 |

| Routine iron use prior to hospitalization | −0.5 (−1.0, 0.1) | 0.03 |

| Routine erythropoietin use prior to hospitalization | −0.8 (−1.4, −0.3) | 0.005 |

| Primary ICU admitting diagnosis Gastrointestinal | 0.5 (−0.3, 1.3) | 0.20 |

| Lung Injury Score at ALI onset | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.2) | 0.38 |

| Patient ICU Course Characteristics | ||

| Platelet transfusionc | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.005) | 0.048 |

| ICU Type | ||

| Surgical (vs. Medical) ICU | 0.6 (0.1, 1.1) | 0.02 |

ICU, intensive care unit; CI, confidence interval; ALI, acute lung injury

Exposure variables presented are those from Table 2 which were associated with a change in mean nadir hemoglobin on the day of first transfusion at p ≤ 0.15.

Mean change in nadir hemoglobin concentration on day of first red blood cell transfusion associated with each 1 unit increase in continuous exposure variables (e.g., age) or each categorical exposure variable (e.g., routine iron use prior to hospitalization) as calculated using multiple linear regression with a random effect to account for clustering of the data within the 3 participating hospitals.

Proportion of patients receiving the ICU intervention at any time from the day of ALI onset through the day of first red blood cell transfusion.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of 249 ALI patients, 47% received a RBC transfusion in the ICU without evidence of active hemorrhage or acute cardiac ischemia. Transfused patients received an average of 5 RBC units in the ICU. The mean nadir hemoglobin on the day of first transfusion of 7.7 g/dL with 15% of patients transfused at a hemoglobin concentration >9g/dL. Despite evaluating 20 patient-related factors, none were independently associated with a higher pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration. However, admission to a surgical (vs. medical) ICU was independently associated with a 0.6 g/dL higher pre-transfusion hemoglobin.

The transfusion practices we observed can be compared to several prior studies. Our observed frequency of transfusion and mean number of RBC units transfused appears similar to other observational studies of general ICU patients.(4, 12–14, 27) Gong and colleagues reported more frequent transfusions with ARDS (61%) than non-ARDS ICU patients (49%).(16) In their cohort of 248 consecutive ALI patients, Netzer and colleagues observed a higher 83.5% transfusion rate; however, this includes RBC transfusions during the patients’ entire hospital course.(17)

Two prior publications observed a pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration similar to our study (7.6 and 7.8 g/dL, respectively).(4, 28) This transfusion threshold is lower than earlier observations by Vincent (8.5 g/dL) and Corwin (8.6 g/dL).(12, 14) Moreover, a recent multi-center randomized trial demonstrated mean pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentrations of 8.0 g/dL and 8.2 g/dL in the placebo and epoetin alfa groups, respectively.(29) Hence, clinical practice appears to be moving toward a more restrictive transfusion strategy since publication of the TRICC trial in 1999.(29)

Literature examining the relationship between patient-related factors and transfusion practices is limited. In a survey of Canadian critical care physicians, Hébert and colleagues presented a variety of clinical scenarios and inquired about clinicians’ transfusion thresholds.(20) They found significant associations between older age and a higher APACHE II score with selection of a transfusion threshold >7 g/dL. Although patient age had a positive association with transfusion threshold in our simple linear regression, it was not independently associated with nadir hemoglobin in our multiple regression model.

Our study did not identify patient-related factors which would account for why two-thirds of non-hemorrhaging ALI patients without active cardiac ischemia are transfused above the threshold recommended by clinical trial evidence. We did observe that pre-hospital iron or erythropoietin use and platelet transfusion in the ICU were associated with a lower pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration. We believe these factors may be markers for a subset of patients with some element of bone marrow suppression in whom clinicians are willing to tolerate a greater degree of anemia prior to transfusion. Future research is required to confirm this hypothesis and understand if pancytopenia is an important factor in the RBC threshold in transfused patients.

Interestingly, our study observed that the pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration was associated with the type of ICU (surgical vs. medical) in which a patient received care. This finding was present after excluding patients with potential bleeding as the cause of transfusion and is independent of the 20 factors related to patients’ demographics, clinical characteristics and ICU course. The observed difference may reflect provider and/or organizational factors influencing transfusion practices, such as the different ICU physician staffing models in surgical versus medical ICUs at our study site hospitals. Alternatively, as with all observational research, our finding may also be influenced by residual or unmeasured confounding by patient-related factors (e.g., incompletely excluding bleeding patients). In their survey of transfusion practices, Hébert and colleagues found that physicians spending a greater proportion of clinical time in the ICU were more likely to chose a restrictive transfusion threshold.(20) Hence, perhaps systematic differences in provider knowledge, attitudes or beliefs(30) regarding the risks and benefits of RBC transfusions in surgical versus medical ICUs may be the underlying explanation for this finding.

Although studies have reported the benefit of instituting policies and protocols on evidence-based transfusion practices,(31, 32) it appears that the many US hospitals, including those participating in our study, have not yet adopted such relatively simple quality improvement strategies.(33) Future studies should further explore barriers and related solutions for improving evidence-based transfusion practice and the potential influence of physician and ICU organizational factors (e.g., transfusion protocols and clinician level of training) on transfusion practices and patient outcomes. Specifically, study designs that employ qualitative or mixed methods may be helpful to understand clinician attitudes and beliefs regarding transfusion thresholds.

There are potential limitations of our study. First, we determined the pre-transfusion hemoglobin based on the nadir hemoglobin on the day of first transfusion. This approach may bias our pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration to be lower than the actual value prompting transfusion in these patients, thus inflating our observed compliance with a restrictive transfusion strategy. Second, by restricting our analysis to the subset of patients who received a RBC transfusion, we could not evaluate factors relevant to the decision regarding whether or not to transfuse a patient. Third, we did not examine the effect of these transfusions on patient outcomes such as mortality. Future studies with greater statistical power and different analytical methodologies will be needed to evaluate patient outcomes. Finally, although this study captures data from 9 ICUs at three different hospitals, generalization of our findings to non-ALI patient populations, other geographic regions, or non-academic medical centers may be limited. However, since the transfusion practices we observed were similar to large studies of general ICU patient populations from both academic and community hospitals across U.S and Europe, this limitation may be minimized.

Conclusion

Approximately half of acute lung injury patients, without bleeding or cardiac ischemia, receive a red blood cell transfusion in the ICU. The observed mean pre-transfusion hemoglobin concentration of 7.7 g/dL is lower than earlier studies, but two-thirds of patients were still transfused above the 7.0 g/dL target hemoglobin concentration suggested by the TRICC trial. Patient factors do not appear to explain this gap between clinical trial evidence and routine practice. Patients admitted to a surgical versus medical ICU were transfused at a hemoglobin concentration that was 0.6 g/dL higher, suggesting that physician behavior or ICU organizational factors may be a greater determinant of the transfusion threshold than patient-related variables.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Acute Lung Injury SCCOR Grant (P50HL73994). Dr. Murphy is supported by an institutional training grant from the NIH (T32 HL007534). Dr. Sevaransky is supported by a Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award from the NIH (KM GM071399). Dr. Netzer is supported by a Clinical Research Career Development Award form the NIH (K12RR023250). Dr. Needham is supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

We thank all participating patients, and the dedicated research staff who assisted with the study: Ms. Rachel Bell, Mr. Victor Dinglas, Ms. Carinda Feild, Dr. Kim Forde, Ms. Thelma Harrington, Dr. Praveen Kondreddi, Ms. Frances Magliacane, Ms. Stacey Murray, Dr. Kim Nguyen, Ms. Amy Scully, Dr. Shabana Shahid, Dr. Kimberly Spillman, and Ms. Elizabeth Miller. We also thank Dr. Eddy Fan for his comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duggan J, O’Connell D, Heller R, et al. Causes of hospital-acquired septicaemia--a case control study. Q J Med. 1993;86(8):479–483. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/86.8.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor RW, Manganaro L, O’Brien J, et al. Impact of allogenic packed red blood cell transfusion on nosocomial infection rates in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(10):2249–2254. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor RW, O’Brien J, Trottier SJ, et al. Red blood cell transfusions and nosocomial infections in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2302–2308. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000234034.51040.7F. quiz 2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shorr AF, Duh MS, Kelly KM, et al. Red blood cell transfusion and ventilator-associated pneumonia: A potential link? Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):666–674. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114810.30477.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shorr AF, Jackson WL, Kelly KM, et al. Transfusion practice and blood stream infections in critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;127(5):1722–1728. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zilberberg MD, Carter C, Lefebvre P, et al. Red blood cell transfusions and the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome among the critically ill: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11(3):R63. doi: 10.1186/cc5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler AA, Hamman RF, Good JT, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome: risk with common predispositions. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(5 Pt 1):593–597. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson LD, Milberg JA, Anardi D, et al. Clinical risks for development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(2 Pt 1):293–301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gajic O, Rana R, Mendez JL, et al. Acute lung injury after blood transfusion in mechanically ventilated patients. Transfusion. 2004;44(10):1468–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pepe PE, Potkin RT, Reus DH, et al. Clinical predictors of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Surg. 1982;144(1):124–130. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, et al. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(12):1499–1507. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French CJ, Bellomo R, Finfer SR, et al. Appropriateness of red blood cell transfusion in Australasian intensive care practice. Med J Aust. 2002;177(10):548–551. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Pearl RG, et al. The CRIT Study: Anemia and blood transfusion in the critically ill--current clinical practice in the United States. Critical Care Medicine. 2004;32(1):39–52. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104112.34142.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hebert PC, Blajchman MA, Cook DJ, et al. Do blood transfusions improve outcomes related to mechanical ventilation? Chest. 2001;119(6):1850–1857. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams P, et al. Clinical predictors of and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: potential role of red cell transfusion. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(6):1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165566.82925.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Netzer G, Shah CV, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Association of RBC transfusion with mortality in patients with acute lung injury. Chest. 2007;132(4):1116–1123. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Needham DM, Dennison CR, Dowdy DW, et al. Study protocol: The Improving Care of Acute Lung Injury Patients (ICAP) study. Critical Care (London, England) 2006;10(1):R9. doi: 10.1186/cc3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hebert PC, Fergusson DA, Stather D, et al. Revisiting transfusion practices in critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2005;33(1):7–12. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000151047.33912.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turgeon AF, Fergusson DA, Doucette S, et al. Red blood cell transfusion practices amongst Canadian anesthesiologists: a survey. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53(4):344–352. doi: 10.1007/BF03022497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Critical Care Medicine. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, et al. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1988;138(3):720–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Medicine. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stata Reference Manual: release 8. College Station, TX: Stata Corp; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao MP, Boralessa H, Morgan C, et al. Blood component use in critically ill patients. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(6):530–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh TS, Garrioch M, Maciver C, et al. Red cell requirements for intensive care units adhering to evidence-based transfusion guidelines. Transfusion. 2004;44(10):1405–1411. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Fabian TC, et al. Efficacy and safety of epoetin alfa in critically ill patients. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(10):965–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(15):1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller U, Exadaktylos A, Roeder C, et al. Effect of a flow chart on use of blood transfusions in primary total hip and knee replacement: prospective before and after study. Bmj. 2004;328(7445):934–938. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7445.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rana R, Afessa B, Keegan MT, et al. Evidence-based red cell transfusion in the critically ill: quality improvement using computerized physician order entry. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(7):1892. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000220766.13623.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hillyer CD, Blumberg N, Glynn SA, et al. Transfusion recipient epidemiology and outcomes research: possibilities for the future. Transfusion. 2008;48(8):1530–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]