Abstract

Oral clearance of lamotrigine, an antiepileptic drug commonly used in pregnant women, is increased in pregnancy by unknown mechanisms. In this study, we show that 17β-estradiol (E2) up-regulates expression of UDP glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A4, the major enzyme responsible for elimination of lamotrigine. Endogenous mRNA expression levels of UGT1A4 in estrogen receptor (ER) α-negative HepG2 cells were induced 2.3-fold by E2 treatment in the presence of ERα expression. E2 enhanced transcriptional activity of UGT1A4 in a concentration-dependent manner in HepG2 cells when ERα was cotransfected. Induction of UGT1A4 transcriptional activity by E2 was also observed in ERα-positive MCF7 cells, which was abrogated by pretreatment with the antiestrogen fulvestrant (ICI 182,780). Analysis of UGT1A4 upstream regions using luciferase reporter assays identified a putative specificity protein-1 (Sp1) binding site (–1906 to –1901 base pairs) that is critical for the induction of UGT1A4 transcriptional activity by E2. Deletion of the Sp1 binding sequence abolished the UGT1A4 up-regulation by E2, and Sp1 bound to the putative Sp1 binding site as determined by a electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Analysis of ERα domains using ERα mutants revealed that the activation function (AF) 1 and AF2 domains but not the DNA binding domain of ERα are required for UGT1A4 induction by E2 in HepG2 cells. Finally, E2 treatment increased lamotrigine glucuronidation in ERα-transfected HepG2 cells. Together, our data indicate that up-regulation of UGT1A4 expression by E2 is mediated by both ERα and Sp1 and is a potential mechanism contributing to the enhanced elimination of lamotrigine in pregnancy.

Human pregnancy is accompanied by various physiological changes, including a dramatic increase in the production of female hormones, i.e., estrogen and progesterone. Blood levels of these hormones rise up to 100-fold by term (Cunningham, 2005). At this high concentration, female hormones manifest functions different from those of their conventional role as gonadal hormones. As a result, various clinical symptoms associated with pregnancy occur, e.g., delayed gastric emptying or intrahepatic cholestasis. Clinical evidence suggests that pregnancy also alters the rate and extent of hepatic drug metabolism (Anderson, 2005; Hodge and Tracy, 2007). Hepatic metabolism is a major elimination route of drugs, and altered drug metabolism during pregnancy can lead to increased drug toxicity or decreased drug efficacy, adversely affecting both the mother and fetus. However, mechanisms underlying altered hepatic drug metabolism in pregnancy are poorly understood.

Lamotrigine is widely prescribed for seizure control in women with child-bearing potential (Sabers et al., 2004; EURAP Study Group, 2006). Of clinical importance to its use during pregnancy, the apparent clearance of lamotrigine increases by 50 to 90% in pregnancy, requiring dosage adjustment to prevent exacerbation of seizures (de Haan et al., 2004; Harden, 2007; Pennell et al., 2008). Lamotrigine is rapidly and completely absorbed from the intestine and undergoes extensive metabolism by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A4 and UGT2B7, with minimal renal excretion (<10%) (Linnet, 2002; Rowland et al., 2006). Because lamotrigine is a low hepatic extraction ratio drug, its clearance is determined by hepatic enzyme activity and plasma protein binding (Rambeck and Wolf, 1993). The intermediate level of plasma protein binding of lamotrigine (∼50%) suggests a minor role of protein binding, but a significant role of intrinsic hepatic enzyme activity, in causing the increase in oral clearance in pregnancy. A recent study reporting an increased ratio of lamotrigine glucuronide metabolite to lamotrigine concentration in pregnancy further supports increased glucuronidation of lamotrigine in pregnancy (Ohman et al., 2008). It is interesting to note that elimination of lamotrigine is similarly increased by use of oral contraceptives (Sabers et al., 2003; Christensen et al., 2007), especially estrogen-based contraceptives (Reimers et al., 2005). This finding suggests that estrogen may be involved in regulating the expression or function of UGT1A4 and/or UGT2B7.

17β-Estradiol (E2), the major estrogen in humans, has been reported to control the expression of several drug-metabolizing enzymes. For example, E2 up-regulates expression of CYP2A6, CYP1B1, and UGT2B15 (Tsuchiya et al., 2004; Harrington et al., 2006; Higashi et al., 2007). In addition, E2 up-regulates Cyp2b10 expression by activating constitutive androstane receptor in mouse (Kawamoto et al., 2000; Mäkinen et al., 2003).

The biological effects of estrogen are mediated through two cognate nuclear receptors, estrogen receptor (ER) α and β. In the liver, ERα is the major subtype expressed (Kuiper et al., 1997). Estrogen binding to ER activates the receptor, leading to interaction with cis-regulatory elements of target genes either by direct binding to estrogen response element (ERE) or by tethering to other transcription factors such as activation protein-1 (AP-1) or specificity protein-1 (Sp1) (Björnström and Sjöberg, 2005). The transactivation by AP-1 or Sp1 has been shown to mediate ERE-independent activation of many estrogen target genes (Safe and Kim, 2008).

We previously showed that UGT2B7 mRNA expression is not influenced by E2 in HepG2 cells (Jeong et al., 2008), ruling out potential up-regulation of UGT2B7 expression by E2. In the present study, we report that E2 activates UGT1A4 expression and the induction of UGT1A4 is mediated by ERα and Sp1. This study presents a potential mechanistic basis for the enhanced elimination of lamotrigine in pregnancy and in oral contraceptive users.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents. 17β-Estradiol was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ICI 182,780 and mithramycin were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO) and BIOMOL Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA), respectively. Lamotrigine and lamotrigine 2N-glucuronide were generous gifts from GlaxoSmithKline (Chapel Hill, NC). Formic acid (ACS grade) and methanol (Optima grade) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Plasmids. ERα expression plasmid (pcDNA3-ER) was previously constructed in our laboratory (Jeong et al., 2008). β-Galactosidase expression plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. William T. Beck (Ee et al., 2004). pGL3-ERE3 is an E2-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid and contains three copies of the ERE from Xenopus vitellogenin A2, located immediately upstream of the thymidine kinase (tk) promoter fused to the luciferase gene (Catherino and Jordan, 1995).

To construct the pGL3-UGT1A4 plasmid, the upstream region of UGT1A4 (–2399 to +28) was PCR-amplified using human genomic DNA (Biochain, Hayward, CA) as the template and a pair of primers: forward and reverse primers of 5′-TGCCTACCACAGACACTAAG-3′ and 5′-TCAGCAGAAGCCACCGAC-3′. The PCR product and NcoI-digested pGL3-basic (Promega, Madison, WI) were blunt-ended by treatment with T4 DNA polymerase and were further digested by HindIII restriction enzyme. The resulting PCR product was cloned into the pGL3-basic vector, yielding pGL3-UGT1A4.

To construct luciferase vectors for deletion assays, three different 5′-flanking regions of UGT1A4 (–2399 to –1643, –1667 to –863, or –862 to +28) were PCR-amplified using pGL3-UGT1A4 as a template and cloned into pGL3tk plasmid that contains the tk promoter fused to the luciferase gene. Additional luciferase reporter plasmids were constructed as follows. Upstream regions of UGT1A4 (–1922 to +28, –1886 to +28, –1835 to +28, –1645 to +28, –1130 to +28, –1074 to +28, and –976 to +28) were PCR-amplified using pGL3-UGT1A4 as a template and each PCR product was cloned into pGL3-basic plasmid that contains promoterless luciferase gene. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Four plasmids expressing different types of mutant ERα were kindly provided by Dr. Doug Harnish (Harnish et al., 1998). These were 1) a mutant with deletion of activation function (AF) 1, 2) a mutant containing nonfunctional AF2 by point mutations, 3) a mutant containing nonfunctional DNA binding domain by point mutations, and 4) a mutant ERα with both deletion of AF1 and point mutations in AF2.

pGL3-UGT1A4-Sp1 Del, where –1905 to –1901 of UGT1A4 was deleted, was constructed by using a QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol, using pGL3-UGT1A4 as the template. All sequences were confirmed by sequencing.

Cell Culture. HepG2 cells from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were cultured in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (MediaTech, Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, Woodland, CA), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 1% minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids. MCF7 cells from American Type Culture Collection were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 6 ng of bovine insulin/ml, 100 units of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 1% minimal essential medium nonessential amino acids. The media were changed 3 days before each experiment to estrogen-free media, i.e., complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing charcoal/dextran-stripped fetal bovine serum (Gemini) and no phenol red.

Luciferase Reporter Assays. HepG2 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml (day 0) and transfected on the next day (day 1) with 0.3 μg of a luciferase construct, 0.3 μg of pcDNA3-ER or control vector (pcDNA3), and 0.1 μgof β-galactosidase expression plasmid using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Sciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h (day 2), the cells were treated with E2 (1 μM) or the ethanol vehicle (0.1%). After a 24-h incubation (day 3), cells were harvested for determination of both luciferase and β-galactosidase activities using assay kits from Promega. MCF7 cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml (day 0) and transfected on the next day (day 1) with a luciferase construct and β-galactosidase expression plasmid using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent. At 3 to 8 h after transfection, the cells were treated with ICI 182,780 (50 μM) or ethanol vehicle. After 24 h (day 2), the cells were treated with E2 (1 μM) or ethanol vehicle. On day 3, the cells were harvested and analyzed for both luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. In all cases, the luciferase activity was normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (unless indicated otherwise) and repeated on at least two separate occasions. Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR. Total RNAs were isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and used as a template for cDNA synthesis with Superscript II (Invitrogen). Using the cDNA as template, qRT-PCR was performed using a Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and SYBR Green PCR MasterMix (Applied Biosystems). The following primers were used: 5′-GAGAGAGGTGTCAGTGGTGGATCT-3′ and 5′-AACAGCCACACGGATGCATA-3′ for UGT1A4, 5′-GTCACGCCCTCCCAGTGT-3′ and 5′-CGAACGGTGTCGTCGAAAC-3′ for pS2, and 5′-ATCCTGGCCTCGCTGTCC-3′ and 5′-CTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACAT-3′ for β-actin. The PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. Amplified products were monitored by measuring the increase of fluorescence intensity from the SYBR Green dye that binds to the double-stranded (ds) DNA amplification product. The dissociation curves for each reaction were examined to ensure amplification of a single PCR product in the reaction. The -fold change in mRNA levels by drug treatment was determined after normalizing the gene expression levels by those of β-actin (2–ΔΔCt method) (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays. 5′-Biotinylated sense and antisense oligonucleotides (–1918 to –1888; CTGTGCAGCCCAGGCCCCTCCTCATCTCCA) harboring the putative Sp1 binding sequence of UGT1A4 (underlined) were annealed to generate the dsDNA probe. The labeled dsDNA probe (0.5 pmol) was incubated with 430 ng of recombinant Sp1 protein (Promega) in 10 μl of reaction buffer [12.5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 6.25 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, 5 μM ZnSO4, 50 mM KCl, and 50 μg/ml bovine serum albumin] (Pascal and Tjian, 1991). To determine the specificity of the binding to the DNA, competition experiments were conducted by coincubation with unlabeled competitors or mithramycin. After a 1-h incubation at room temperature, protein-DNA complexes were separated on 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel at 4°C, transferred onto a nylon membrane, and visualized using streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase and chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Determination of Lamotrigine Glucuronide Concentration. Concentrations of lamotrigine 2N-glucuronide in cell culture media were determined by using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (3200 QTRAP system; Applied Biosystems) equipped with an electrospray ion source. Separation was performed with a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C8 column (4.6 × 50 mm, 3.5 μm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The following linear gradient of the mobile phase, consisting of water [0.1% (v/v) formic acid] and methanol, was used for separation: 15% methanol at time 0 increased to 90% at 7 min. Lamotrigine glucuronide was detected in the positive ion mode by examining an ion pair of 432.2/256.0. Midazolam 4-hydroxide was used as an internal standard (ion pair of 341.9/324.0). The limit of quantification was approximately 1 ng/ml.

Results

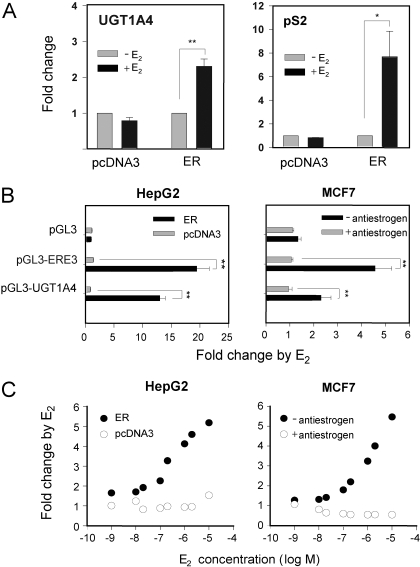

Induction of UGT1A4 Expression by E2. To examine the effect of E2 on the expression of UGT1A4, we initially used ERα-negative HepG2 cells transfected with a plasmid expressing ERα (pcDNA3-ER) or an empty plasmid (pcDNA3). Upon treatment of cells with E2, mRNA levels of UGT1A4 were determined by qRT-PCR. The expression level of pS2, a known estrogen-responsive gene (Barkhem et al., 2002), was determined as a positive control. In ERα-transfected HepG2 cells (called HepG2/pcDNA3-ER), pS2 expression was increased 7-fold by E2 treatment compared with vehicle treatment, confirming that our model system is responsive to E2 (Fig. 1A). In the same cells, UGT1A4 expression was increased significantly by E2 treatment (>2-fold) compared with that in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 1A), whereas no induction was observed in cells transfected with pcDNA3. These results indicate that E2 induces UGT1A4 expression through an ERα-mediated mechanism.

Fig. 1.

Effect of E2 on UGT1A4 expression. A, HepG2 cells were seeded onto a 12-well plate at 1.5 × 105 cells/ml, and on the next day they were transfected with 0.6 μg of pcDNA3-ER or control vector (pcDNA3) using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent. After 16 to 18 h, the cells were treated with E2 (1 μM) or vehicle control (ethanol). After a 72-h incubation, mRNA levels of pS2 and UGT1A4 were determined by qRT-PCR and normalized by those of β-actin. Results represent -fold change relative to the vehicle control (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. B, HepG2 cells were transfected with luciferase constructs (pGL3-basic, pGL3-ERE3, or pGL3-UGT1A4) and pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3), along with the β-galactosidase expression plasmid (for normalization of transfection efficiency). MCF7 cells were transfected with the luciferase constructs and β-galactosidase expression plasmid and subsequently were treated with the antiestrogen ICI 182,780 (or ethanol). The transfected HepG2 or MCF7 cells were treated with 1 μME2 (or ethanol) for 24 h, and luciferase assays were performed (see Materials and Methods). Results represent -fold change relative to vehicle control (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). **, p < 0.01. C, HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pGL3-UGT1A4, pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3), and a β-galactosidase expression plasmid. MCF7 cells were transfected with pGL3-UGT1A4 and the β-galactosidase expression plasmid and subsequently were treated with ICI 182,780 (or ethanol). The transfected cells were treated with E2 in different concentrations, and a luciferase assay was performed. Data presented are the mean of results obtained from a duplicate experiment.

Transcriptional activation of UGT1A4 by E2 was further examined by using a luciferase reporter system. We constructed a reporter plasmid pGL3-UGT1A4, which carries an upstream region of UGT1A4 (from –2399 to +28) fused to a luciferase reporter gene. ERα-negative HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pGL3-UGT1A4 and pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3), and ERα-positive MCF7 cells were transfected with pGL3-UGT1A4. Each cell line was also transfected with pGL3-ERE3 as a positive control for estrogen responsiveness (see Materials and Methods) and pGL3-basic empty vector as a negative control. The transfected cells were then treated with either E2 or vehicle control, and luciferase activity was determined.

The HepG2 and MCF7 cells transfected with control plasmids, pGL3-basic, and pGL3-ERE3, respectively, displayed the expected response to E2 (Fig. 1B). Upon treatment with E2, HepG2/pcDNA3-ER and MCF7 cells transfected with pGL3-UGT1A4 exhibited increased luciferase activity (Fig. 1B): a 13-fold increase in HepG2/pcDNA3-ER cells and a 2.5-fold increase in MCF7 cells compared with vehicle-treated cells. Induction of UGT1A4 transcriptional activity in MCF7 cells was abrogated by treatment with an ERα-degrading antiestrogen, ICI 182,780 (Osborne et al., 2004) (Fig. 1B), further supporting the notion that ERα mediates the up-regulation of UGT1A4 expression by E2. In both HepG2/pcDNA3-ER and MCF7 cells, E2 increased UGT1A4 transcriptional activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). No significant induction by E2 was observed in HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3 and MCF7 cells treated with the antiestrogen. Taken together, these results demonstrate that E2 up-regulates UGT1A4 expression, and this induction requires ERα.

Identification of a cis-Regulatory Element Required for UGT1A4 Induction by E2. Because induction of UGT1A4 expression by E2 required the presence of ERα (Fig. 1), we analyzed the transcriptional regulatory region of UGT1A4 for existence of potential EREs using Dragon ERE Finder and Possum programs that can also identify putative AP-1 and Sp1 binding sites (Bajic et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2004). Indeed, this analysis retrieved multiple putative EREs as well as AP-1 and Sp1 binding sites within the ∼2.4-kilobase transcriptional regulatory region of UGT1A4.

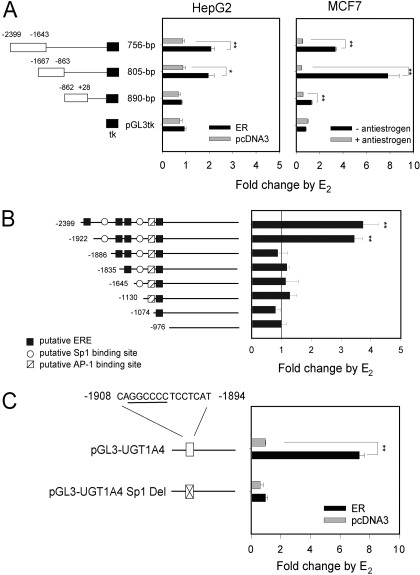

To approximately map E2-responsive regulatory regions of UGT1A4, we analyzed the 2.4-kilobase upstream region of UGT1A4 by using a luciferase reporter system. A DNA fragment (2399 to –1643, –1667 to –863, or –862 to +28) that contains varying numbers of ERE or binding sites for AP-1 or Sp1 was fused to a constitutive tk promoter linked to the luciferase gene (Fig. 2A). These luciferase constructs were transiently transfected into HepG2 (along with pcDNA3-ER) and MCF7 cells, and E2-responsiveness was determined. As shown in Fig. 2A, the –2399 to –863 of UGT1A4 transcription regulatory region was found to be responsible for the induction of UGT1A4 expression by E2. This region contains four putative EREs, one AP-1, and two Sp1 binding sites (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional regulatory region mediating UGT1A4 induction by E2. A, luciferase constructs containing different segments of the UGT1A4 5′-flanking region proximal to the tk promoter were cotransfected into HepG2 cells with pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3) and β-galactosidase expression plasmid. pGL3tk is a luciferase vector containing the tk promoter only. MCF7 cells were transfected with the luciferase constructs and β-galactosidase expression plasmid and treated with ICI 182,780 (or ethanol). The transfected HepG2 or MCF7 cells were treated with 1 μME2 (or ethanol) for 24 h, and the luciferase assay was performed. Results represent -fold change relative to vehicle control (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. B, HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3-ER (or pcDAN3), 5′-nested deletion constructs of pGL3-UGT1A4, and β-galactosidase expression plasmid. The transfected HepG2 cells were treated with 1 μME2 (or ethanol) for 24 h, and the luciferase assay was performed. Results represent -fold change relative to vehicle control (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). **, p < 0.01 versus ethanol-treated group. C, HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3), β-galactosidase expression plasmid, and pGL3-UGT1A4-Sp1 Del, where the putative Sp1 binding site (underlined) of pGL3-UGT1A4 was deleted. The transfected cells were treated with 1 μME2 (or ethanol) for 24 h, and the luciferase assay was performed. Results represent -fold change relative to vehicle control (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). **, p < 0.01.

To specifically identify E2-responsive cis-elements within the –2399 to –863 region of UGT1A4, we systematically deleted the potential binding sites of ER, AP-1, or Sp1 from the pGL3-UGT1A4 and checked for a loss of E2 responsiveness (Fig. 2B). A 5′-nested deletion construct of pGL3-UGT1A4 was transiently transfected into HepG2 cells along with pcDNA3-ER, and E2 responsiveness was determined. Deletion of a region containing the most distal ERE, –2399 to –1923, caused almost no change in E2-mediated induction of luciferase activity. However, subsequent deletion of a region carrying a putative Sp1-binding site, –1922 to –1887, led to a complete loss of E2 responsiveness (Fig. 2B). The essential role of the putative Sp1 binding site in UGT1A4 regulation by E2 was further verified by using another luciferase reporter, pGL3-UGT1A4-Sp1 Del. This plasmid harbors the UGT1A4 transcriptional regulatory region (–2399 to +28) that lacks the Sp1 binding site (Fig. 2C). HepG2 cells transfected with pGL3-UGT1A4-Sp1 Del exhibited no response to E2, in contrast to those transfected with pGL3-UGT1A4 that contains the intact transcriptional regulatory region. Taken together, these results suggest that the DNA sequence between –1922 and –1887, containing a putative Sp1 binding site, is required for the induction of UGT1A4 transcriptional activity by E2.

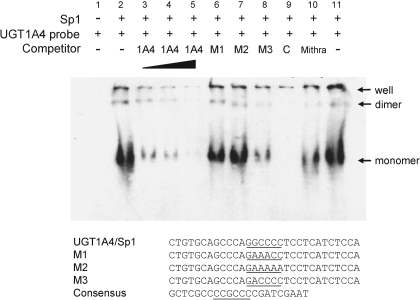

Sp1 Protein Binds to the Putative Sp1 Binding Site. We next investigated whether Sp1 binds to the putative Sp1 binding site of UGT1A4 (called UGT1A4/Sp1). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed using recombinant Sp1 and a DNA fragment (–1918 to –1888) containing UGT1A4/Sp1 as a probe. As reported previously (Pascal and Tjian, 1991), we observed multiple shifted bands that appear to represent homomultimeric complexes of Sp1 (Fig. 3). Direct binding of Sp1 to the UGT1A4/Sp1 was indicated by 1) the appearance of mobility-shifted bands (lane 2), 2) the disappearance of the bands upon competition by a unlabeled UGT1A4/Sp1 probe (lanes 3–5) or a DNA probe containing a known consensus Sp1-binding site (lane 9), 3) the inability of M1 and M2 probes (each containing a mutated version of the UGT1A4/Sp1 sequence) to compete for Sp1 binding (lanes 6–7), and 4) the partial blockade of the interaction by mithramycin (lane 10), a known inhibitor of Sp1 binding to DNA.

Fig. 3.

Binding of Sp1 to the putative Sp1 binding site in the UGT1A4 upstream region. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed using recombinant Sp1 protein and a biotinylated probe (–1918 to –1888) containing UGT1A4/Sp1. Upon observing multiple bands on the gel (see text for more details), we used an electrophoresis running time long enough to release unbound (free) DNA from the gel to better resolve the bands (thus, free DNA probes are not visible on the gel). Unlabeled UGT1A4/Sp1 probe was used as competitors at 5-, 10-, and 40-fold molar excess (lanes 3–5). In addition, unlabeled UGT1A4/Sp1 probes containing the mutated Sp1 binding sequences (M1, M2, and M3; lanes 6–8) or unlabeled DNA probe containing consensus Sp1 binding sequence (C, lane 9) were used as competitors at 40-fold molar excess. Mithramycin, a known inhibitor of Sp1 binding to DNA, was added to the binding reaction at 100 nM (lane 10). Underlined sequences are putative or consensus Sp1 binding sites of probes. The antisense strand of consensus Sp1 binding sequence is shown for better visualization of sequence homology to UGT1A4/Sp1.

The M3 probe differed from the sequence of the original UGT1A4/Sp1 probe at a single nucleotide position and bound Sp1 with lower affinity (lane 8). These observations, together with results obtained from the luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 2C), suggest that direct binding of Sp1 is required for up-regulation of UGT1A4 expression by E2.

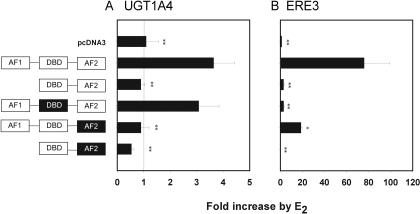

DNA Binding Domain of ERα Is Not Required for UGT1A4 Regulation by E2. To investigate the role of ERα in up-regulation of UGT1A4 transcription by E2, we used plasmid constructs containing one of the following mutated versions of ERα: 1) ERα with deletion of AF1, 2) ERα with point mutations in the DNA binding domain, 3) ERα with point mutations in the C-terminal AF2, and 4) ERα with deletion of AF1 and point mutations in AF2. The point mutations result in loss of functionality in the relevant domains (Harnish et al., 1998). HepG2 cells cotransfected with pGL3-UGT1A4 and one of the ERα mutants were examined for E2-responsiveness. HepG2 cells cotransfected with pGL3-ERE3 and one of the ERα mutants served as controls.

Deletion of the AF1 domain and/or mutation of the AF2 domain completely abolished the E2 responsiveness of UGT1A4 (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the E2 responsiveness of UGT1A4 was retained when the DNA binding domain of ERα was nonfunctional (Fig. 4A). The same mutation led to a complete loss of E2 responsiveness in the cells transfected with pGL3-ERE3 (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the AF1 and AF2 domains of ERα, but not the DNA binding domain, play a critical role in up-regulation of UG1A4 expression by E2.

Fig. 4.

Role of ERα domains in UGT1A4 induction by E2. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pGL3-UGT1A4 (A) or pGL3-ERE3 (B) along with β-galactosidase expression plasmid and one of plasmids containing ERα mutants (see text for details). The black box domain represents inactivation by point mutations. The transfected cells were treated with 1 μME2 (or ethanol), and the luciferase assay was performed. Results represent -fold change relative to vehicle control (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus cells transfected with wild-type ERα. DBD, DNA-binding domain.

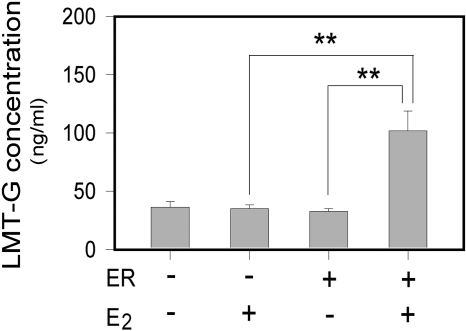

Correlation between UGT1A4 Transcription and Enzymatic Activity. The E2-mediated up-regulation of UGT1A4 expression was examined using lamotrigine as a UGT1A4 substrate. HepG2 cells transfected with pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3) were treated with E2 (or ethanol) for 48 h, and then lamotrigine was added to the culture media. After a 24-h incubation, the concentrations of lamotrigine 2N-glucuronide in the media were determined. As shown in Fig. 5, in HepG2/pcDNA3-ER cells, E2 treatment increased production of the glucuronide metabolite 3-fold compared with that in vehicle-treated cells. This result shows that the up-regulation of UGT1A4 transcription by E2 leads to increased UGT1A4 enzyme activity.

Fig. 5.

Effect of E2 on lamotrigine glucuronidation. HepG2 cells were seeded onto a 12-well plate at 1.5 × 105 cells/ml, and on the next day they were transfected with 0.6 μg of pcDNA3-ER (or pcDNA3) using FuGENE 6. After 3 to 8 h, the cells were treated with E2 (1 μM) or ethanol vehicle. After a 48-h incubation, the media were changed to contain lamotrigine at a final concentration of 40 μM. After a 24-h incubation, the media were collected and concentrations of lamotrigine 2N-glucuronide (LMT-G) in the media were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Data presented are concentrations of LMT-G in the media (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). **, p < 0.01.

Discussion

Clinical data show that oral clearance of lamotrigine increases in pregnancy by 50 to 90% (de Haan et al., 2004; Harden, 2007; Pennell et al., 2008). This increase may be attributed partially to fetal or placental expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Substantial enzyme activity has been observed in fetal liver microsomes for certain UGTs (de Wildt et al., 1999). However, the similar degree of increase in lamotrigine clearance in women during pregnancy and oral contraceptive use (Sabers et al., 2003; Christensen et al., 2007) suggests a prominent role of UGT1A4 and/or UGT2B7 activity in the maternal liver in contributing to the pregnancy-related changes.

We have previously shown that UGT2B7 mRNA expression is not influenced by E2 in HepG2 cells (Jeong et al., 2008), ruling out potential up-regulation of UGT2B7 expression by E2. In the present study, using HepG2 and MCF7 cells as our model systems, we show that E2 up-regulates UGT1A4 expression. We also attempted to use a more physiologically relevant system, freshly isolated human hepatocytes. However, we did not observe significant induction of UGT1A4 expression by E2 in primary human hepatocytes (data not shown). This discrepancy between results obtained in HepG2 cells and primary human hepatocyte is not uncommon. In fact, transcription of most UGT1A genes in human hepatocytes is not readily inducible by typical enzyme inducers, including rifampin (Soars et al., 2004). For example, although clinical findings indicate up-regulation of both CYP3A4 and UGT1A1 activities by rifampin, the -fold increase in UGT1A1 activities by rifampin was negligible (0.5–1.4-fold) compared with the significant increase in CYP3A4 activity (2–17-fold) in human hepatocytes (Soars et al., 2004). These results appear to suggest that to study up-regulation of UGT1A expression, there is a need for a model system other than primary hepatocytes.

To elicit the E2 response in HepG2 or MCF7 cells, we used a relatively high concentration of E2,1 μM (Fig. 1). This high concentration reflects physiological E2 levels attained in pregnancy and potential accumulation of E2 in the liver (Schleicher et al., 1998), the major site of E2 metabolism. It is interesting to note that even at this high concentration, maximal effects of E2 on ERα-mediated transactivation were not obtained in our experimental system (Fig. 1C). This finding is somewhat contrary to previous reports in which the maximal response to E2 of its target genes was shown at 1 to 10 nM in MCF7 cells (Wijayaratne et al., 1999). Although the underlying mechanism for this discrepancy is unclear, differences in experimental conditions, e.g., use of different batches of charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, may be responsible. It is noteworthy that our parallel study using pGL3-ERE3 exhibited a pattern of concentration dependence similar to that of pGL3-UGT1A4 (i.e., saturation not reached at 1 μM; data not shown) in HepG2/pcDNA3-ER cells, suggesting that the transcriptional regulatory region of UGT1A4 responds to E2 in a similar manner as the consensus ERE does, at least in our experimental system.

Our luciferase assay results obtained from the tk promoter were slightly different from those obtained from an intact UGT1A4 promoter (Fig. 2, A and B). The UGT1A4 upstream region, –1666 to –863, exhibited E2-mediated induction in a tk promoter-based luciferase construct; an effect not verified using the native UGT1A4 promoter-based luciferase construct. This discrepancy probably arises from differential recruitment of transcription factors in the two different promoters, which can subsequently influence interaction with transcription factors bound to upstream enhancers (Thomas and Chiang, 2006). This observation emphasizes the importance of cross-validation of promoter assay results using native promoters.

Our data suggest that the UGT1A4-inducing activity of E2 is probably mediated by ERα and Sp1. Previous studies report the role of E2 as an inducer of the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes, including CYP1B1 and CYP2A6 (Tsuchiya et al., 2004; Higashi et al., 2007). Up-regulation of CYP1B1 and CYP2A6 by E2 is mediated by the classic mechanism of ERα action (Tsuchiya et al., 2004; Higashi et al., 2007); ERα, activated upon E2 binding, translocates into the nucleus and, subsequently, induces the expression of target genes by binding to ERE in their transcriptional regulatory regions. On the other hand, in this study, the E2 effect on UGT1A4 expression was found to be mediated by a nonclassic mechanism of ERα action. Our results show that the induction of UGT1A4 by E2 requires binding of Sp1 to a putative binding site within the transcriptional regulatory region of UGT1A4. Thus, Sp1, rather than ERα, is the likely factor directly binding to the UGT1A4 upstream sequence and activating UGT1A4 expression. Furthermore, the DNA binding domain of ERα is not required for induction of the UGT1A4 transcriptional activity by E2 (Fig. 4), whereas the AF1 and AF2 domains are necessary (Fig. 4). The AF1 and AF2 domains are known to be critical for ERα dimerization and ligand binding, as well as ERα interaction with other transcriptional regulators, such as Sp1, to form a transcriptional complex (Sun et al., 1998; Castro-Rivera et al., 2001). In fact, ERα was previously shown to enhance the formation and stability of the Sp1-DNA complex, although the direct formation of ternary ERα-Sp1-DNA complexes could not be detected (Safe and Kim, 2008). Likewise, in our study, it remains to be characterized how E2-activated ERα interacts with Sp1 in the cells and whether factors in addition to ERα are involved in the ERα-Sp1 interaction for regulation of UGT1A4 expression.

The transcription factor, Sp1, plays a critical role in cell differentiation and proliferation. Sp1 also mediates hormonal regulation of gene expression (Safe and Kim, 2008). It is interesting to note that many drug-metabolizing enzyme genes contain putative Sp1 binding sites in their transcriptional regulatory regions (K. Yang and H. Jeong, unpublished data), suggesting that possibly Sp1 is broadly involved in controlling the expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes.

In conclusion, we show that UGT1A4 is up-regulated by E2 in a manner requiring both ERα and Sp1. The results suggest that increased expression of hepatic UGT1A4 resulting from elevated E2 contributes to altered metabolism of UGT1A4 substrate drugs in pregnancy and provide a potential mechanistic basis for the increased lamotrigine clearance in pregnancy and in oral contraceptive users.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. William T. Beck and Stacy Shord for reading the manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and Dr. Hyunwoo Lee for critical suggestions and comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [Grant HD055313 and Fellowship K12HK055892]. The study was conducted in a facility constructed with support from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources [Grant C06-RR15482].

H.C. and K.Y. contributed equally to this work.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://dmd.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/dmd.109.026609.

ABBREVIATIONS: UGT, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase; E2, 17β-estradiol; ER, estrogen receptor; ERE, estrogen response element; AP1, activation protein-1; Sp1, specificity protein-1, ICI 182,780, fulvestrant; tk, thymidine kinase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; AF, activation function; qRT, quantitative real-time; ds, double-stranded.

References

- Anderson GD (2005) Pregnancy-induced changes in pharmacokinetics: a mechanistic-based approach. Clin Pharmacokinet 44 989–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajic VB, Tan SL, Chong A, Tang S, Ström A, Gustafsson JA, Lin CY, and Liu ET (2003) Dragon ERE Finder version 2: a tool for accurate detection and analysis of estrogen response elements in vertebrate genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 31 3605–3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkhem T, Haldosén LA, Gustafsson JA, and Nilsson S (2002) pS2 Gene expression in HepG2 cells: complex regulation through crosstalk between the estrogen receptor α, an estrogen-responsive element, and the activator protein 1 response element. Mol Pharmacol 61 1273–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björnström L and Sjöberg M (2005) Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol 19 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rivera E, Samudio I, and Safe S (2001) Estrogen regulation of cyclin D1 gene expression in ZR-75 breast cancer cells involves multiple enhancer elements. J Biol Chem 276 30853–30861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catherino WH and Jordan VC (1995) Increasing the number of tandem estrogen response elements increases the estrogenic activity of a tamoxifen analogue. Cancer Lett 92 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Petrenaite V, Atterman J, Sidenius P, Ohman I, Tomson T, and Sabers A (2007) Oral contraceptives induce lamotrigine metabolism: evidence from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia 48 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham FG (2005) Implantation, embryogenesis, and placental development, in Williams Obstetrics pp 70–82, McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division, New York.

- de Haan GJ, Edelbroek P, Segers J, Engelsman M, Lindhout D, Dévilé-Notschaele M, and Augustijn P (2004) Gestation-induced changes in lamotrigine pharmacokinetics: a monotherapy study. Neurology 63 571–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wildt SN, Kearns GL, Leeder JS, and van den Anker JN (1999) Glucuronidation in humans: pharmacogenetic and developmental aspects. Clin Pharmacokinet 36 439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ee PL, Kamalakaran S, Tonetti D, He X, Ross DD, and Beck WT (2004) Identification of a novel estrogen response element in the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) gene. Cancer Res 64 1247–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EURAP Study Group (2006) Seizure control and treatment in pregnancy: observations from the EURAP epilepsy pregnancy registry. Neurology 66 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden CL (2007) Pregnancy and epilepsy. Semin Neurol 27 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnish DC, Evans MJ, Scicchitano MS, Bhat RA, and Karathanasis SK (1998) Estrogen regulation of the apolipoprotein AI gene promoter through transcription cofactor sharing. J Biol Chem 273 9270–9278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington WR, Sengupta S, and Katzenellenbogen BS (2006) Estrogen regulation of the glucuronidation enzyme UGT2B15 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 147 3843–3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi E, Fukami T, Itoh M, Kyo S, Inoue M, Yokoi T, and Nakajima M (2007) Human CYP2A6 is induced by estrogen via estrogen receptor. Drug Metab Dispos 35 1935–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge LS and Tracy TS (2007) Alterations in drug disposition during pregnancy: implications for drug therapy. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 3 557–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Choi S, Song JW, Chen H, and Fischer JH (2008) Regulation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 by progesterone and its impact on labetalol elimination. Xenobiotica 38 62–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto T, Kakizaki S, Yoshinari K, and Negishi M (2000) Estrogen activation of the nuclear orphan receptor CAR (constitutive active receptor) in induction of the mouse Cyp2b10 gene. Mol Endocrinol 14 1897–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Häggblad J, Nilsson S, and Gustafsson JA (1997) Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors α and β. Endocrinology 138 863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnet K (2002) Glucuronidation of olanzapine by cDNA-expressed human UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and human liver microsomes. Hum Psychopharmacol 17 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkinen J, Reinisalo M, Niemi K, Viitala P, Jyrkkärinne J, Chung H, Pelkonen O, and Honkakoski P (2003) Dual action of oestrogens on the mouse constitutive androstane receptor. Biochem J 376 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman I, Beck O, Vitols S, and Tomson T (2008) Plasma concentrations of lamotrigine and its 2-N-glucuronide metabolite during pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia 49 1075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CK, Wakeling A, and Nicholson RI (2004) Fulvestrant: an oestrogen receptor antagonist with a novel mechanism of action. Br J Cancer 90 (Suppl 1): S2–S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal E and Tjian R (1991) Different activation domains of Sp1 govern formation of multimers and mediate transcriptional synergism. Genes Dev 5 1646–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell PB, Peng L, Newport DJ, Ritchie JC, Koganti A, Holley DK, Newman M, and Stowe ZN (2008) Lamotrigine in pregnancy: clearance, therapeutic drug monitoring, and seizure frequency. Neurology 70 2130–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambeck B and Wolf P (1993) Lamotrigine clinical pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 25 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers A, Helde G, and Brodtkorb E (2005) Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations. Epilepsia 46 1414–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland A, Elliot DJ, Williams JA, Mackenzie PI, Dickinson RG, and Miners JO (2006) In vitro characterization of lamotrigine N2-glucuronidation and the lamotrigine-valproic acid interaction. Drug Metab Dispos 34 1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabers A, Dam M, A-Rogvi-Hansen B, Boas J, Sidenius P, Laue Friis M, Alving J, Dahl M, Ankerhus J, and Mouritzen Dam A (2004) Epilepsy and pregnancy: lamotrigine as main drug used. Acta Neurol Scand 109 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabers A, Ohman I, Christensen J, and Tomson T (2003) Oral contraceptives reduce lamotrigine plasma levels. Neurology 61 570–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S and Kim K (2008) Non-classical genomic estrogen receptor (ER)/specificity protein and ER/activating protein-1 signaling pathways. J Mol Endocrinol 41 263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher F, Täuber U, Louton T, and Schunack W (1998) Tissue distribution of sex steroids: concentration of 17β-oestradiol and cyproterone acetate in selected organs of female Wistar rats. Pharmacol Toxicol 82 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD and Livak KJ (2008) Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 3 1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soars MG, Petullo DM, Eckstein JA, Kasper SC, and Wrighton SA (2004) An assessment of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase induction using primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos 32 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Porter W, and Safe S (1998) Estrogen-induced retinoic acid receptor α1 gene expression: role of estrogen receptor-Sp1 complex. Mol Endocrinol 12 882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S, Han H, and Bajic VB (2004) ERGDB: Estrogen Responsive Genes Database. Nucleic Acids Res 32 D533–D536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MC and Chiang CM (2006) The general transcription machinery and general cofactors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 41 105–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y, Nakajima M, Kyo S, Kanaya T, Inoue M, and Yokoi T (2004) Human CYP1B1 is regulated by estradiol via estrogen receptor. Cancer Res 64 3119–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayaratne AL, Nagel SC, Paige LA, Christensen DJ, Norris JD, Fowlkes DM, and McDonnell DP (1999) Comparative analyses of mechanistic differences among antiestrogens. Endocrinology 140 5828–5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]