To the Editor: Older adults are less likely than younger adults to participate in research. It remains unclear, however, whether this difference is due to recruitment issues, consent processes, eligibility criteria, participant burden or other factors.1,2 Each of these issues may affect research design, sample representativeness and, ultimately, the ability to generalize research findings to an older adult population.

In an effort to understand contemporary factors that may influence decisions to participate in minimal risk research, we systematically reviewed 59 clinical investigations published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society over a 6-month period (August 2006-January 2007). Our goals in conducting this literature review were: 1) to estimate the proportion of older adults that were invited, but refused to participate in minimal-risk research; 2) to determine what factors reportedly were associated with refusal to participate.

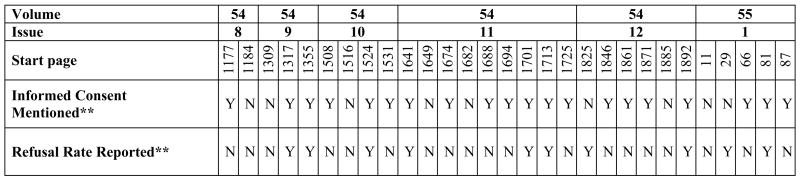

Of the 59 articles considered, 29 met criteria for review (see Table 1); that is, the studies were conducted in the U.S., required consent/assent and were minimal risk. Retrospective and anonymous survey studies were excluded. Studies were most often excluded because they were conducted outside of the U.S. Two independent raters (RV and JM) completed a structured abstraction form to identify level of risk (minimal versus greater than minimal risk, based on current National Institutes of Health guidelines).3

We attempted to abstract rates of participant refusal and reasons for refusal from the articles as well. Refusals were coded separately from other non-participation factors, such as ineligibility, “failure to contact” or withdrawal after consent. Unfortunately, refusal information was seldom explicitly stated, resulting in a low inter-rater agreement (50%) between reviewers. That difficulty was resolved by using a 3-person consensus panel (RV, JM, JK) to re-evaluate all studies.

About one-third of the articles reported refusal rates and none of the articles described actual reasons for refusal. When reported, the average refusal rate across studies was 29% (SD=17%). Seven articles referenced other published sources for more detailed methodological information, but only two of these secondary sources provided additional information on participant refusals. Participants and refusers were compared in 10% (n=3) of articles, and these studies found that a) African-Americans, and/or older potential participants were less likely to participate, or b) there were no apparent differences between consenters and non-consenters.2,4,5

To develop insight into how the research topic might impact participation, the 3-person panel categorized studies by type of outcome: 1) functional status (i.e., basic/instrumental activities of daily living, n=11); 2) health and healthcare related outcomes (i.e., specific diagnoses, healthcare utilization, dietary supplements, n=16); and 3) subjective/opinion studies (i.e., perceptions of care quality, patient opinions, n=2). When compared, there were no statistical differences in refusal rates across study types. However, studies of functional status tended to report refusal rates more often (55%) than studies of health and healthcare (19%). Functional status studies had higher actual refusal rates (34%) than health related studies (21%).

Basic information on human subjects issues (e.g., informed consent, institutional review board approval) was also abstracted. Strikingly, we found that “informed consent” was mentioned in only 69% (n=20) of articles despite explicit instructions to authors6 to include this information in the Methods section of submitted papers.

DISCUSSION & RECOMMENDATIONS

While refusal information is customarily included in the reporting of randomized controlled trials and survey research, the minimal risk studies reviewed were unlikely to report refusal rates. Among studies that did report refusal rates, more than one in four potential participants refused. Most articles reported no detailed information about reasons for refusals, characteristics of those who refused to participate or about the consent process.

While we recognize that reporting extensive detail on participant refusal and human subjects issues may not be feasible or desirable, we believe that the proportion of eligible participants who refuse to participate and the most common reasons for refusal should be briefly stated in all research reports. In addition, we respectfully recommend that all authors follow the published instructions and report the acquisition of informed consent in their papers. By making information on refusal rates and other human subjects issues available, researchers may be able to address barriers to participation and facilitate more formalized research on these topics. These measures could be achieved within a participant flow diagram or in a brief section of text, perhaps referencing more detailed electronic information. The model already exists and is used in other journals, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association.7 We recommend that The Editor and our colleagues embrace this approach.

Figure 1.

Reporting of consent processes and refusal rates in 29 published research articles on minimal risk studies. *

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by: NIA K23 AG028452 (Martin); UCLA Claude Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Career Development Award (Martin; P60 AG010415; PI Reuben), Archstone Foundation Grant 05-01-01 (Vivrette); the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, and Research Service of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. The authors report conflicts of interest.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding sources had no influence on the study concept or design, the analysis or interpretation of data or the conclusions drawn.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sugarman J, McCrory DC, Hubal RC. Meaningful informed consent from older adults: a structured literature review of empirical reserach. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Boykin MJ, et al. The relationship between sociodemographic factosr and oral health-related quality of life in dentate and edentulous community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1701–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (online) Code of Federal Regulations: 45 CFR 46.102(i) [Accessed 10/26/2007]; Available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/45cfr46.htm#46.102.

- 4.Sanford JA, Griffiths PC, Richardson P, Hargraves K, Butterfield T, Hoenig H. The effects of in-home rehabilitatino on self-efficacy in mobility impaired adults: a randomized, clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1641–1648. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert SM, Bear-Lehman J, Burkhardt A. Disparities between ambient, standard lighting and retinal acuities in community-dwellnig older people; implications for disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1713–1718. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Instructions to authors. [Accessed 11/16/2007];Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (online) Available at http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/submit.asp?ref#0002-8614&site=1.

- 7.JAMA instructions for authors. [Accessed 10/26/07];Journal of the American Medical Association (online) Available at http://jama/ama-assn.org/misc/ifora.dtl#ManuscriptFileFormats.