Abstract

Although previous research has identified various child-specific and contextual risk factors associated with externalizing behaviors, there is a dearth of literature examining child × context interactions in the prospective prediction of externalizing behaviors. To address this gap, we examined autonomic functioning as a moderator of the relation between contextual factors (i.e., neighborhood cohesion and harsh parental behaviors) and externalizing behaviors. Participants were an ethnic minority, inner-city sample of first through fourth grade children (N = 57, 50% male) and their primary caregivers who participated in two assessments approximately 1 year apart. Results indicated that baseline sympathetic functioning moderated the relation between (a) neighborhood cohesion and externalizing behaviors and (b) harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors. Post-hoc probing of these interactions revealed that higher levels of neighborhood cohesion prospectively predicted (a) higher levels of externalizing behaviors among children with heightened baseline sympathetic functioning, and (b) lower levels of externalizing behaviors among children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning. In addition, among children with heightened baseline sympathetic functioning, higher levels of harsh parental behaviors prospectively predicted higher levels of externalizing behaviors.

Keywords: externalizing behaviors, neighborhood, parenting, autonomic functioning

Childhood externalizing behavior problems, which include hostile, aggressive, oppositional, and defiant behaviors, are associated with numerous negative sequelae, including low academic achievement, internalizing symptoms, and poor interpersonal relationships (Campbell, Spieker, Burchinal, Poe, NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2006; MacDonald & Achenbach, 1999). Thus, much research has been devoted to identifying factors that may confer risk for externalizing behaviors, which can have implications for etiological and preventative models. Contextual factors, such as neighborhood characteristics and parenting behaviors, and child-specific factors (e.g., autonomic functioning) consistently have been related to increased rates of childhood externalizing symptoms. For example, research has demonstrated that children who are impoverished and live in dangerous neighborhoods are at increased risk for externalizing problems (Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994; Schonberg & Shaw, 2007). However, there is a paucity of research that concurrently addresses contextual and child-specific factors and potential child × context interactions in the prediction of externalizing behaviors. This is unfortunate given that children likely differ in their sensitivity to contextual factors based on biological and cognitive processes (Belsky, 2005; Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 2000). Therefore, consideration of child variables is critical for understanding the relations between contextual factors and externalizing behaviors.

We used a developmental psychopathology perspective in the present study to address several gaps in the literature. Specifically, we considered (a) factors that can be arranged from more distal to more proximal to the child, (b) child × context interactions, and (c) potential risk and protective factors (Brofenbrenner, 1979; Cicchetti, 1993; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). In terms of the distal to proximal factors, we considered broader contextual variables (i.e., neighborhood characteristics), family variables (i.e., parenting behaviors), and child-specific variables (i.e., autonomic functioning). Because children likely have transactional relations with multiple systems, we examined child × context interactions to explore the conditions under which children may differ in their sensitivity to parenting and neighborhood characteristics. We also chose to include contextual factors that may be associated with increased risk for or resilience to externalizing behaviors (harsh parental behaviors and neighborhood cohesion, respectively). Furthermore, because of a limited body of work examining child × context interactions among impoverished samples, and the finding that children of ethnic minority descent are more likely to reside in impoverished neighborhoods in urban areas (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004), we examined these interactions among an ethnic minority sample of children residing in the inner city. Our primary objective was to evaluate whether children’s autonomic functioning moderated the relations between (a) neighborhood cohesion and externalizing problems and (b) harsh parental behaviors and externalizing problems using a prospective design in an inner-city sample.

In terms of neighborhood factors, neighborhood violence may confer risk for externalizing behaviors (Schwartz & Proctor, 2000), whereas neighborhood cohesion (i.e., active involvement, friendship, and supportive relations with peer and adult neighbors) may serve a protective function or buffer children from the development of externalizing behaviors (Silk, Sessa, Morris, Steinberg, & Avenevoli, 2004). Higher levels of neighborhood cohesion are thought to facilitate the collective socialization and supervision of neighborhood children (Jencks & Mayer, 1990), which, in turn, may provide higher levels of emotional support for the child (Silk et al., 2004). Despite its potential protective influence, neighborhood cohesion has received little attention relative to neighborhood danger and violence. Given that cohesion may be more prevalent within neighborhoods that are composed predominantly of ethnic minority families (Seidman et al., 1998), and given that ethnic minority families are disproportionately represented in inner-city neighborhoods (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004), researchers examining externalizing behaviors among inner-city children would do well to consider neighborhood cohesion.

Several family-level factors, such as interparental conflict, parental alcohol and substance use, parental psychopathology, and harsh parental behaviors, also are associated with the development of childhood externalizing problems (El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, 2001; Shannon, Beauchaine, Brenner, Neuhaus, & Gatzke-Kopp, 2007). We focused on the relation between harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors for several reasons. First, parental rejecting and harsh discipline strategies are concurrently and prospectively associated with externalizing behaviors (Bender et al., 2007; Côté, Vaillancourt, Barker, Nagin, & Tremblay, 2007; Knutson, DeGarmo, Koeppi, & Reid, 2005). Second, harsh parental behaviors may be less strongly related to the development of externalizing behaviors among ethnic minority (particularly African-American), as compared to European-American, samples (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Hill & Bush, 2001). This discrepancy suggests that ethnic minority children may differ in their sensitivity to harsh parental behaviors; thus, we evaluated harsh parental behaviors given our goal of examining child × context interactions in the prediction of externalizing behaviors among ethnic minority children.

To understand why contextual factors place some, but not all, children at risk for the development of externalizing behaviors, various researchers have recommended examining endogenous biological factors concurrently with contextual factors (Belsky, 2005; Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 2000). This line of research suggests that exposure to stressful environments in childhood heightens stress reactivity, which increases the capacity to detect and respond to environmental dangers. Furthermore, children experiencing heightened stress reactivity or an increased biological sensitivity to context are hypothesized to (a) be at risk for negative psychological and health outcomes under conditions of adversity, and (b) experience positive outcomes under conditions of support (Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2008). Given our focus on an inner-city sample who likely experience contextual adversity and given that autonomic functioning discriminates between children with high and low levels of stress reactivity (Ellis, Essex, & Boyce, 2005), we examined whether two potential markers of increased biological sensitivity (i.e., sympathetic and parasympathetic functioning) affect the relations between contextual factors and externalizing behaviors.

As a brief overview, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) controls basic visceral functions of the body, such as cardiovascular activity and metabolism, and is composed of two divisions, the parasympathetic (PNS) and sympathetic (SNS) nervous systems. Generally speaking, the SNS regulates involuntary reactions to stress (e.g., increased heart and breathing rates, stimulation of sweat glands) and prepares the body for action in the context of stressors. The PNS, in contrast, promotes growth and restorative processes. Sympathetic activation is indexed by pre-ejection period (PEP), and shorter PEPs are associated with sympathetic activation. Parasympathetic cardiac influences are indexed by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), or the waxing and waning of heart rate across the respiratory cycle (Porges, 1995). RSA typically is used as an estimate of vagal tone because it is a proxy for regulatory processes that cannot readily be measured non-invasively. In terms of the relation between RSA and vagal tone, RSA results from decreases in vagal efference during inhalation, which increase heart rate, and increases in vagal efference during exhalation, which decrease heart rate (Beauchaine, 2001). Measurement of PEP and RSA at rest appear to reflect temperamental reactivity and emotionality (Beauchaine, 2001), whereas measurement during challenge or in response to a stressor indexes reactivity and self regulation (Porges, Doussard-Roosevelt, Portales, & Greenspan, 1996). We used PEP and RSA at both baseline and the change from baseline to task (hereafter “reactivity”) to index autonomic functioning.

The ANS is thought to provide the physiological states necessary to support different classes of social behaviors and emotion regulation. Specifically, vagal influence is hypothesized to support social engagement behaviors (i.e., calming, self-soothing; Porges, 2007). Consistent with this possibility, increased vagal tone is associated with children’s social engagement (Fox & Field, 1989) and social competence (Eisenberg et al., 1995). Vagal withdrawal is hypothesized to support mobilization behaviors, such as fight and flight, and moderate vagal withdrawal has been associated with higher levels of positive social behaviors and lower levels of behavioral problems (Porges, 2007). Vagal deficiencies (i.e., decreased RSA at baseline and lower levels of RSA modulation) have been related to externalizing behaviors among children and adolescents in ethnically diverse samples (Beauchaine, Katkin, Strassberg, & Snarr, 2001; Crowell et al., 2006; Mezzacappa et al., 1997; Pine et al., 1998) and this relation appears to develop between preschool and middle childhood (Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, 2007). Given that both SNS and PNS contribute to patterns of cardiac activity and the potential for concurrent sympathetic and parasympathetic dysregulation (Beauchaine, 2001), we also considered measures of sympathetic functioning (i.e., PEP). Attenuated SNS measures, including baseline and reactivity measures, are associated with externalizing behaviors across various developmental periods (preschool, middle childhood, and adolescence; Beauchaine et al., 2007).

Physiological measures also have been related to a number of contextual factors, including neighborhood and parenting characteristics. For instance, contextual disadvantage, as indexed by neighborhood quality or SES, is related to elevated psychophysiological stress (i.e., increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure) among impoverished and ethnic minority children and adolescents (Evans & English, 2002; Wilson, Kliewer, Plybon, & Sica, 2000). To date, however, research often examines broader measures of psychophysiological stress (e.g., blood pressure) and has not examined whether child-specific factors moderate the relation between neighborhood characteristics, more specifically, and externalizing problems. Thus, it remains unclear whether SNS and PNS make independent contributions to the relation between neighborhood factors and externalizing behaviors or whether children differ in their sensitivity to neighborhood characteristics.

As would be hypothesized based on theories of biological sensitivity to contextual influences, PNS functioning and vagal tone indices have been found to moderate the relation between parental variables and externalizing behaviors. For example, higher resting RSA and RSA reactivity among children exposed to marital conflict, marital hostility, or parental problem drinking may protect these children from increased externalizing problems (El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh et al., 2001; Katz & Gottman, 1995), suggesting that not all children exposed to negative familial variables are at increased risk for externalizing behaviors. Little work has examined sympathetic functioning as a moderator of relations between contextual factors and externalizing behaviors. However, Ellis and colleagues (2005) reported that children exposed to high levels of adversity have higher levels of SNS reactivity than children experiencing low and moderate levels of adversity. Coupled with arguments that children with heightened biological sensitivity who experience stress are at greater risk for negative outcomes (Boyce & Ellis, 2005), we might expect that contextual risk factors (e.g., harsh parental behaviors) would be associated with externalizing behaviors among children with high levels of SNS functioning (i.e., baseline and reactivity). Alternatively, given evidence that attenuated SNS functioning is associated with externalizing behaviors (Beauchaine et al., 2007), one also could predict that children with high levels of SNS functioning may have lower levels of externalizing behaviors as compared to those with attenuated SNS functioning. A more specific examination of the potential moderating role of contextual factors is necessary to examine these alternative possibilities.

In sum, this investigation represents the first study to test whether children’s autonomic functioning moderates the relation between (a) neighborhood cohesion and externalizing problems and (b) harsh parental behaviors and externalizing problems, using a prospective design in an inner-city sample. We examined these relations among young children as our goal was to identify factors that are associated with externalizing behaviors at a point when these processes may be amenable to intervention, and prior to the development of additional negative sequelae. In addition, we examined these processes among inner-city children because children residing in impoverished neighborhoods are at elevated risk for externalizing problems (Attar et al., 1994; Evans & English, 2002). Given work by Beauchaine and colleagues (2007), we expected that children with longer PEP scores at baseline and decreased PEP reactivity would have higher levels of externalizing behaviors than children with shorter PEP scores at baseline and increased PEP reactivity. Given previous findings (El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh et al., 2001; Katz & Gottman, 1995), in terms of moderation, we expected that heightened baseline RSA and RSA reactivity (i.e., vagal withdrawal) would attenuate the relation between harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors. In addition, we expected that higher levels of harsh parental behaviors would be associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors among children with shorter PEP scores at baseline and increased PEP reactivity. Last, we hypothesized that baseline RSA and RSA reactivity, as well as baseline PEP and PEP reactivity, would moderate the relation between neighborhood cohesion and externalizing behaviors. However, given the dearth of literature examining relations among RSA, PEP, neighborhood factors, and externalizing behaviors, we did not make directional hypotheses about these relations.

Method

Participants

Participants were 57 children (M = 7.77 ±1.08 years old; 50% male, 94% African-American, 6% Latino/a) and their primary caregivers (84% biological mothers) from three elementary schools in North Philadelphia. The neighborhoods from which families were drawn can be characterized as an inner city area, with high levels of crime, poverty, and homogeneity in terms of ethnic minority status. In terms of family configurations, 47.6% of children lived in single-parent households, 31.7% lived in intact (i.e., two-biological parent) households, 9.5% lived in blended homes, and 8% lived in other family configurations (grandparental, adoptive). In terms of annual family income, 64% of families earned less than $20,000, 21% earned from $20,000–$30,000, and 15% earned over $30,000. Sixty-seven percent of the children lived in families receiving public assistance. Fifty-three percent of the primary caregivers had completed high school, 29% less than high school, and 18% beyond high school.

Children and their primary caregivers were assessed at two time points, on average 10.7 (± 1.3) months apart. In the present analyses, we examined children who participated at both time points. Children who participated at both time points did not differ (all ps > .05) from those who completed only the initial visit (N = 88) in terms of age, t(76) = .52; sex, χ2(1) =.06; ethnicity, χ2(1) = .07; family configuration, χ2(4) = 1.44; or income, t(71)= 1.39 (all ps > .05).

Procedure

The present study was part of a larger research program designed to follow contextually at-risk children and their caregivers over time. The study was approved by a University Institutional Review Board. The project director obtained permission from the principals of three elementary schools to send information regarding the project to primary caregivers (hereafter “parents”) of first- through third-grade children. The families were mailed a description of the study, parental consent form, and a self-addressed, stamped postcard. The description stated that we were interested in children’s social, physical, and emotional adjustment. Parents interested in participating in the project either returned a self-addressed stamped postcard or called to make an appointment. The sample characteristics (i.e., ethnicity, sex, family SES) reflect the schools from which the families were drawn; nevertheless, due to confidentiality requirements, no information was available to compare those who self-selected into the project and those that did not.

At the first time point (Time 1), parents and their children were invited to our research lab for 2 visits, each lasting approximately 2.5 hours. Parents and children provided consent and assent, respectively, prior to participation. Parents completed questionnaires related to their child and family. The child participated in a protocol designed to measure autonomic functioning and reported on neighborhood factors. Approximately 9 months after their initial visit, parents were sent a cover letter inviting them to participate in the project again, a consent form, and self-addressed stamped postcard. As with Time 1, parents could either return the postcard or call to make an appointment. Parents and their children were invited to our research lab for 1 visit, lasting approximately 2.5 hours (Time 2). Parents completed questionnaires regarding the child’s externalizing behaviors. At both time points, parents were paid for their participation and reimbursed for transportation, children received a small gift, and a donation was made to the school for every child who participated.

Measures

Demographics

Parents provided information about their child’s sex and household income at Time 1. Household income was measured on a scale from 1 (0 to $9,999) to 5 (Over $40,000).

Neighborhood cohesion

Given that a child’s perception of contextual factors influences context-outcome relations (Boyce et al., 1998) and to minimize mono-rater, mono-method biases, we used a puppet interview to obtain children’s reports of neighborhood cohesion at Time 1. This 11-item subscale was part of a larger puppet interview that has been shown to be a reliable and valid assessment instrument for children (Sessa, Avenevoli, Steinberg, & Morris, 2001; Silk et al., 2004). The puppet interview is administered to children individually, and children’s responses are videotaped for later coding by trained research assistants (κs range from .98 to 1.00). Children are presented with two puppets that offer opposing statements and are asked to pick which puppet is more like them (Silk et al., 2004). Responses were scored as 0 or 1, where 1 indicated the presence of cohesion. The mean of the summed items was used to create a neighborhood cohesion score (α = .72). Sample items include, “We talk to our neighbors/we do not talk to our neighbors” and “I talk to the grown-ups in my neighborhood/I do not talk to the grown-ups in my neighborhood.” Previous research (Silk et al., 2004) indicates good internal consistency and convergent validity, as children’s reports of cohesive neighborhoods were associated with greater adult presence in the neighborhood and lower levels of poverty.

Harsh parental behaviors

Parents completed the Parenting Measure (Sessa et al., 2001) at Time 1, which asks parents to endorse items related to how they have parented their child during the previous month on a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). The subscale measuring harsh parental behaviors was used in the present study (5 items, α = .62). Sample items include, “I snap at my child when s/he gets on my nerves,” “When s/he upsets me, I lose my patience and punish him/her more severely,” and “When my child does something wrong, I sometimes threaten him/her.” Previous studies using ethnically and socioeconomically diverse samples have demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α =.68) and expected convergent and divergent validity with other indices of parental behaviors (Sessa et al., 2001; Silk et al., 2004).

Autonomic functioning

Autonomic functioning was measured at Time 1 using Bio-Impedance Technology’s HIC-2000 (Chapel Hill, NC, n.d.), a noninvasive instrument for detecting and monitoring bioelectric impedance signals. An external electrocardiographic (ECG) cable was added to the HIC-2000 to increase the flexibility for electrode positioning and ease of detecting the ECG signal. The HIC-2000 recorded RSA and PEP with a constant 5 V potential across 7 electrodes that were pre-gelled and had a circular contact area with a 1cm diameter. Disposable spot electrodes were attached to the child’s neck, back, stomach, and shoulder (Qu, Zhang, Webster, & Tompkins, 1986). Cardiac signals were monitored by and interfaced to a PC-based computer.

Both RSA and PEP were measured during tasks chosen to provide a range of stressors (i.e., social, cognitive, physical, and emotional; Alkon et al., 2003; Bubier & Drabick, 2008). The protocol has been shown to be a reliable and valid method for examining sympathetic and parasympathetic responses to challenge among children (Alkon et al., 2003). For each child, the order of the tasks was as follows: social (3 min), cognitive (3 min), physical (1 min), and emotional (3 min). The social challenge was designed to engage the child in conversation and included questions about the child’s school, family, and interests. In the cognitive challenge, the child repeated a list of 2 to 6 numbers presented orally by the experimenter. In the physical challenge, the child was asked to taste and identify several drops of lemon juice that were placed on his or her tongue by the experimenter. The emotional challenge consisted of two brief video clips designed to evoke emotional reactions (i.e., fear and sadness). The “fear” video depicts a young boy who is frightened during a thunderstorm and the “sadness” video depicts a child and her mother addressing the loss of the child’s pet bird (Alkon et al., 2003; Eisenberg et al., 1988). Age-appropriate books were read to the child before and after the challenge tasks to obtain baseline measures of resting autonomic functioning. During baseline and each of the tasks, the child’s behavior and physiological reactions (i.e., heart rate, RSA, and PEP) were monitored. This standardized protocol took approximately 20 min to administer.

Sympathetic-linked cardiac activity was indexed by PEP, measured as the interval from the beginning of ventricular depolarization (ECG Q wave) to the onset of ventricular ejection (impedance cardiographic B wave; Sherwood et al., 1990). Waveforms were collected using the spot electrode configuration described above (Qu et al., 1986). PEP data were ensemble-averaged in Cop-Win 6.0 H software in 30 s epochs. It is important to note that shortened PEP scores are consistent with activation of the SNS. Parasympathetic cardiac activity was assessed using spectral analysis via Nevrokard’s Long-Term Heart Rate Variability (LT-HRV) software (Ljubljana, Slovenia, n.d.), which separates heart rate variability time series into component frequencies using fast-Fourier transformations (Berntson et al., 1997). High frequency spectral power (>.15 Hz) was extracted to measure RSA. This high frequency band is a better index of cardiac vagal control, as compared to low frequency (< .04 Hz) or midfrequency (.04 – .15 Hz) variability (Houtveen & Molenaar, 2001; Mezzacappa, Kindlon, Earls, & Saul, 1994). Spectral densities were calculated in 30 s epochs. The log of RSA was used to index parasympathetic functioning, which is a common transformation used to normalize spectral analytic data (Crowell et al., 2006). Mean scores for PEP and RSA were calculated at baseline and the difference score (mean across each of the four challenge tasks minus mean at baseline) was used as a measure of autonomic reactivity (Alkon et al., 2003; Bubier & Drabick, 2008). Therefore, reactivity refers to the shortening of PEP and vagal withdrawal. Participants were included in the analyses if they had at least 50% scorable epochs within each task and during baseline. This decision was made to maximize the number of participants included while maintaining an adequate number of epochs.

Externalizing behaviors

Parents rated externalizing behaviors at Time 2 using 11 items from the Child Symptom Inventory-4 (CSI-4; Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994, 2002), which is a screening instrument for behavioral symptoms of most Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) childhood disorders. Items were rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (almost always) (α = .92). Eight of these items reflect hostile, oppositional, and defiant behaviors (consistent with oppositional defiant disorder symptoms), and the remaining 3 aggressive items were drawn from the conduct disorder symptom category and include “bullies others,” “starts physical fights,” and “purposely destroys property.” The mean score was used. The validity of the CSI-4 has been examined in scores of studies and includes comparisons with dimensional rating scales, laboratory measures, chart diagnoses, and structured psychiatric interviews; comparisons between symptomatic and asymptomatic samples and between samples with specific behavioral syndromes; and response to behavioral and pharmacological interventions (Gadow & Sprafkin, 1994, 2002, 2006).

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate correlations were conducted to examine relations among study variables. Independent sample t-tests (boys vs. girls) were conducted to evaluate sex differences for each variable. To examine whether autonomic measures moderated the relation between (a) harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors and (b) neighborhood cohesion and externalizing behaviors, regression analyses were conducted for which externalizing behavior was the dependent variable. Child sex and family income were entered in the first step to account for these variables (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, & Aber, 1997). In the second step, a contextual factor (i.e., neighborhood cohesion or harsh parental behaviors), a measure of autonomic functioning (i.e., PEP or RSA), and the context × autonomic functioning cross-product interaction term were entered. Using a medium effect size as an estimate, with 3 predictors (contextual variable, autonomic measure, and context × autonomic functioning interaction term), a minimum sample of 55 is needed to attain sufficient power (.80; α = .05) when the predictors are reliable (Aiken & West, 1991). To minimize multicollinearity, the independent variables and their interactions were centered (M = 0) before inclusion in the regression equations (Aiken & West, 1991). For significant interaction terms, we conducted post-hoc probing of moderational effects using procedures outlined by Holmbeck (2002).

Results

Bivariate correlations, means, standard deviations, and ns for study variables are presented in Table 1. Bivariate correlations indicated that harsh parental behaviors were associated with longer PEP scores at baseline (r = .44, p < .01) and higher levels of externalizing behaviors (r = .45, p < .01). Independent sample t-tests indicated that boys were rated as having higher levels of externalizing behaviors, t(55) = 2.09, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .59. In addition, boys exhibited greater PEP reactivity, t(40) = 2.88, p < .01, d = 1.31. The sex difference for harsh parental behaviors tended toward significance, with parents of boys reporting higher levels of harsh parental behaviors than parents of girls, t(54) = 1.99, p < .10, d = .54.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family income | - | |||||||

| 2. PEP Baseline | .17 | - | ||||||

| 3. PEP Reactivity | .26 | .18 | - | |||||

| 4. RSA Baseline | −.00 | −.09 | −.17 | - | ||||

| 5. RSA Reactivity | −.02 | .11 | .23 | −.76** | - | |||

| 6. Neighborhood cohesion | .15 | −.05 | .12 | −.08 | .15 | - | ||

| 7. Harsh parental behaviors | .08 | .44** | .18 | −.13 | .19 | −.02 | - | |

| 8. CSI-4 externalizing behaviors | .07 | .29† | .03 | −.15 | .11 | −.04 | .45** | - |

| M | 2.20 | 97.87 | .95 | 4.02 | .41 | .75 | 1.88 | .50 |

| SD | 1.25 | 12.55 | 2.56 | .41 | .69 | .21 | .50 | .52 |

| n | 55 | 43 | 42 | 37 | 36 | 57 | 56 | 57 |

Note. PEP = pre-ejection period (index of sympathetic nervous system), RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia (index of parasympathetic nervous system), CSI-4 = Child Symptom Inventory-4.

p < .01,

p < .10.

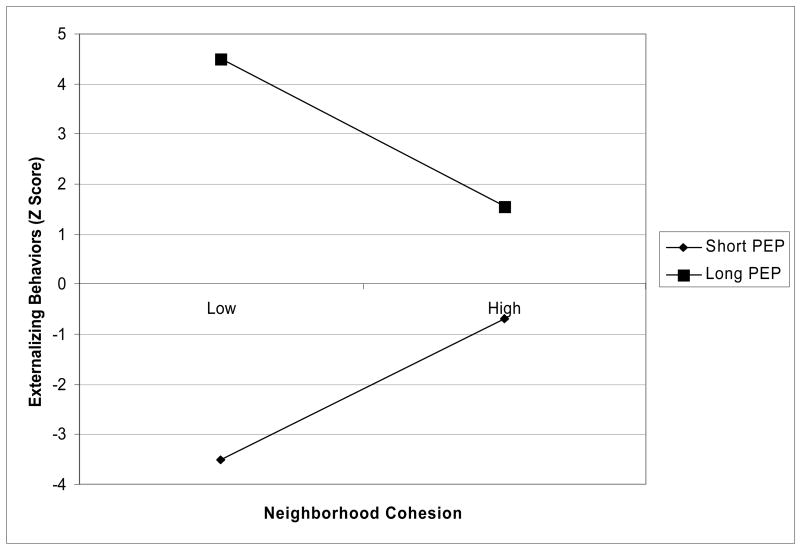

Regression analyses indicated that, after controlling for child sex and family income, the cohesion × PEP baseline interaction term predicted externalizing behaviors (Table 2). Following procedures described by Aiken and West (1991) and Holmbeck (2002) for probing and graphing significant interactions, we computed two new conditional moderator variables (± 1 SD from the mean of PEP baseline) and new interactions that incorporated the conditional variables. We then ran two post-hoc regressions, each of which involved simultaneous entry of neighborhood cohesion, one of the conditional PEP baseline variables, and the neighborhood cohesion × conditional PEP baseline variable (Holmbeck, 2002). From these analyses, we derived unstandardized betas (slopes) and a regression equation for children experiencing short (1 SD below the mean) and long (1 SD above the mean) PEP scores at baseline (Figure 1). The slope was significantly different from zero for short (B = 3.14, t(39) = 2.41, p < .05, d = .93) and long (B = −3.29, t(39) = −2.45, p < .05, d = .96) PEP scores at baseline, indicating that the effect of short and long PEP scores at baseline on externalizing behaviors differed for children with low vs. high neighborhood cohesion. Examination of Figure 1 indicates that for children with long PEP scores at baseline, high neighborhood cohesion was associated with lower levels of externalizing behaviors, whereas low neighborhood cohesion was associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors. Among children with short PEP scores at baseline, high neighborhood cohesion was associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors, whereas low neighborhood cohesion was associated with lower levels of externalizing behaviors.

Table 2.

Regression Analysis Summary for Neighborhood Cohesion, PEP Baseline, and Their Interaction in Predicting Externalizing Behaviors (n = 42)

| Step and Variable | B | SE B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .13 | .13† | .15 | |||

| Child sex | −.41 | .17 | −.35* | |||

| Family income | .03 | .07 | .06 | |||

| Step 2 | .32 | .19* | .23 | |||

| Neighborhood cohesion | −.13 | .09 | −.22 | |||

| PEP Baseline | .18 | .08 | .33* | |||

| Cohesion × PEP Baseline | −.25 | .11 | −.34* |

Note. PEP = pre-ejection period (index of sympathetic nervous system), f2 = effect size.

p < .05,

p < .10.

Figure 1.

Relation between neighborhood cohesion and externalizing behaviors among children with long (1 SD above mean) vs. short (1 SD below mean) PEP scores at baseline.

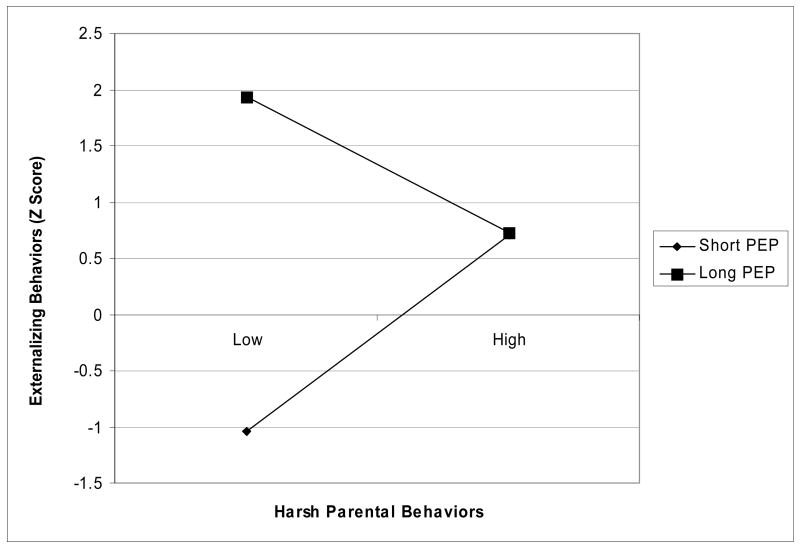

After controlling for demographic factors, the harsh parental behaviors × PEP baseline interaction term also predicted externalizing behavior (Table 3). Post-hoc probing indicated that the slope was not significantly different from zero for long PEP scores at baseline (B = −1.34, t(39) = −1.51, p = .14, d = .37). For short PEP scores at baseline, the slope was significant (B = 1.94, t(38) = 2.03, p < .05, d = .67), indicating that the impact of short PEP scores at baseline on externalizing behaviors differed for children with low vs. high levels of harsh parental behaviors. Examination of Figure 2 indicates that among children with short PEP scores at baseline, higher levels of harsh parental behaviors were associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors. Interaction terms involving RSA variables and PEP reactivity with harsh parental behaviors and neighborhood cohesion did not significantly predict externalizing behaviors (Table 4).

Table 3.

Regression Analysis Summary for Harsh Parental Behaviors, PEP Baseline, and Their Interaction in Predicting Externalizing Behaviors (n = 41)

| Step and Variable | B | SE B | β | R2 | ΔR2 | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .13 | .13† | .15 | |||

| Child sex | −.41 | .18 | −.35* | |||

| Family income | .03 | .07 | .06 | |||

| Step 2 | . | .35 | .22* | .28 | ||

| Harsh Parental Behaviors | .56 | .11 | .41* | |||

| PEP Baseline | .05 | .09 | .08 | |||

| Parenting × PEP Baseline | −.17 | .08 | −.32* |

Note. PEP = pre-ejection period (index of sympathetic nervous system), f2 = effect size.

p < .05,

p < .10.

Figure 2.

Relation between harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors among children with long (1 SD above mean) vs. short (1 SD below mean) PEP scores at baseline.

Table 4.

Regression Beta Weights for Nonsignificant Interaction Terms in Predicting Externalizing Behaviors

| Interaction Term | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesion × PEP Reactivity | .07 | .17 | .08 |

| Parenting × PEP Reactivity | −.01 | .10 | −.01 |

| Cohesion × RSA Baseline | −.00 | .13 | −.01 |

| Parenting × RSA Baseline | −.10 | .11 | −.16 |

| Cohesion × RSA Reactivity | −.10 | .11 | −.19 |

| Parenting × RSA Reactivity | .12 | .10 | .18 |

Note. PEP = pre-ejection period (index of sympathetic nervous system), RSA = respiratory sinus arrhythmia (index of parasympathetic nervous system).

Discussion

We used a developmental psychopathology perspective in the present study to evaluate children’s autonomic functioning as a moderator of the relation between contextual factors (i.e., neighborhood cohesion and harsh parental behaviors) and externalizing problems using a prospective design. Significant findings were specific to baseline sympathetic functioning and revealed that baseline sympathetic measures moderated the relation between (a) neighborhood cohesion and externalizing behaviors and (b) harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors among ethnic minority children living in the inner-city. These results lend further support to the hypothesis that children differ in their sensitivity to contextual factors based on biological and cognitive processes (Belsky, 2005; Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Steinberg & Avenevoli, 2000). This study contributes to the extant literature by providing the first empirical demonstration of the moderating effects of baseline sympathetic measures on contextual factors in the prospective prediction of externalizing behaviors.

Results demonstrating relations among neighborhood cohesion, baseline sympathetic functioning, and externalizing behaviors partially supported our hypotheses, and extend previous research documenting relations between neighborhood cohesion and externalizing behaviors (Silk et al., 2004) and between neighborhood characteristics and psychophysiological stress (Evans & English, 2002; Wilson et al., 2000). Specifically, in the present study, higher levels of neighborhood cohesion prospectively predicted (a) lower levels of externalizing behaviors among children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning, and (b) higher levels of externalizing behaviors among children with heightened baseline sympathetic functioning. This suggests that neighborhood cohesion may buffer the risk for externalizing problems among children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning, who are at elevated risk for externalizing behaviors (Beauchaine et al., 2007; Crowell et al., 2006). However, rather than demonstrating a consistently positive effect on externalizing behaviors, neighborhood cohesion also was predictive of externalizing behaviors among children who have heightened baseline sympathetic functioning and consequently are hypothesized to be biologically sensitive to context (Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2008). This pattern of findings thus is counter to predictions that would emerge from the biological sensitivity to context literature. It is possible that our use of child self-reported neighborhood cohesion may have affected these results. For example, perhaps children who are more biologically sensitive to context provide different reports of their neighborhoods than children who are less biologically sensitive to context, and their perceptions of context differentially affects their engaging in externalizing behaviors. Moreover, given the sample characteristics, this relation may be more specific to disadvantaged neighborhoods, which are often dangerous and are associated with greater exposure to crime, residential mobility, and environmental stressors (e.g., noise, overcrowding; Gorman-Smith & Tolan, 1998; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Wandersman & Nation, 1998). Because this is the first study to our knowledge to examine the inter-relations among neighborhood cohesion and autonomic measures, these results require replication.

Our findings also build on previous work indicating that autonomic measures moderate the relation between parenting factors and externalizing problems (El-Sheikh, 2005; El-Sheikh et al., 2001; Katz & Gottman, 1995) and that harsh parental behaviors are associated with externalizing problems (Côté et al., 2007; Knutson et al., 2005). Specifically, our results suggest that harsh parental behaviors were associated with (a) lower levels of externalizing behaviors among children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning, and (b) higher levels of externalizing behaviors among children with heightened baseline sympathetic functioning. Consistent with hypotheses, this suggests that children experiencing heightened stress reactivity or biological sensitivity to context (Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2008) are at significant risk for the development of externalizing behaviors when subjected to high levels of harsh parental behaviors. It is noteworthy that harsh parental behaviors were associated with somewhat lower levels of externalizing behaviors among children who are thought to be at elevated risk for externalizing behaviors (i.e., children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning). This pattern of results may partially account for the decreased association between harsh parental behaviors and externalizing behaviors among ethnic minority (in particular, African-American) children (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Hill & Bush, 2001).

Our findings are also consistent with previous research indicating that children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning are at risk for externalizing behaviors (Beauchaine et al., 2007). Specifically, in the present study, children with attenuated baseline sympathetic functioning exhibited higher levels externalizing behaviors than children with heightened baseline sympathetic functioning. These findings make it feasible to reconcile the work of Beauchaine et al. with the biological sensitivity to context literature. Specifically, children residing in impoverished, inner-city neighborhoods who experience heightened baseline sympathetic functioning may be at risk for externalizing behaviors in the context of harsh parental behaviors and specific neighborhood characteristics, whereas children with attenuated sympathetic baseline functioning consistently exhibit elevated levels of externalizing behaviors regardless of contextual factors.

Several findings were inconsistent with hypotheses. First, sympathetic reactivity did not moderate the relation between contextual factors and externalizing behaviors. This finding may be explained by the significant sex difference that was found with boys exhibiting a greater change in sympathetic functioning from baseline to task, as compared to girls. For example, interrelations among sympathetic reactivity, contextual factors, and externalizing behaviors may have been attenuated as a result of combining boys and girls in the model. Therefore, future research examining these relations may benefit from investigating separate models among boys and girls, as research indicates important sex differences with regard to prevalence of and risk factors related to externalizing behaviors (e.g., Drabick, Beauchaine, Gadow, Carlson, & Bromet, 2006) and the relation between autonomic functioning and externalizing behaviors (Beauchaine, Hong, & Marsh, 2008). Because of limited power, we did not test separate models among boys and girls in the present study.

Second, baseline parasympathetic functioning and parasympathetic reactivity did not moderate the relation between contextual factors and externalizing behaviors. The lack of findings related to parasympathetic functioning may be a function of the age of our sample; that is, children in the present study may not have evidenced the relation between attenuated parasympathetic activity and externalizing behaviors that appears to come “online” in middle childhood (Beauchaine et al., 2007). Previous work that demonstrates the buffering role of heightened parasympathetic functioning among children exposed to marital conflict and parental problem drinking is consistent with this explanation. For example, the average age of children in the El-Sheikh studies (2001, 2005) was approximately two years older than the current sample.

Strengths of the study include the prospective design and the examination of these processes in an inner-city sample. Understanding how contextual factors influence physiological functioning among a high-risk sample has implications for intervention efforts that potentially can preclude or mitigate behavioral and psychological difficulties. Also, we extended previous research on autonomic functioning that has typically examined heart rate and skin conductance by including RSA and PEP indices, which permitted examination of the independent contributions of the PNS and SNS. However, to develop ecologically valid biological models of externalizing behaviors, these results must be replicated in other samples. It also may be useful to examine relations between ANS systems through concurrent consideration of SNS and PNS functioning to determine whether the associations among these child and contextual factors differ when SNS and PNS processes are considered jointly. Last, the use of objective indicators of autonomic functioning, as well as multiple reporters and indices, minimizes concerns related to mono-rater and mono-method biases.

Despite these strengths, the present study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, suggesting that we may have been underpowered to detect effects. Indeed, the required sample size for a moderate effect size increases dramatically as the reliability of the predictors decreases, with required sample sizes of 108 and 155 when reliabilities are .80 and .70, respectively (Aiken & West, 1991). In addition, ethnicity and SES were confounded. Therefore, future research should examine different ethnic groups with varying SES levels to determine the generalizability of the present findings. If the results generalize to varying SES and ethnic groups, this would suggest that the present findings are generally characteristic of children with externalizing behaviors. If the findings do not generalize, these results may suggest that contextual factors (e.g., poverty, neighborhood characteristics) exert a more important or proximal influence on ANS functioning and externalizing behavior problems among children who reside in the inner city (Evans & English, 2002). In addition, we assessed PEP and RSA at the same time point as contextual factors; therefore, we could not evaluate prospective and bidirectional relations between autonomic functioning and contextual factors. Early adverse environments may modify the child’s biological functioning such that the child subsequently exhibits a heightened response to stress. This may be especially likely for children residing in inner city areas, as dangerous neighborhoods may increase the risk of a child’s witnessing or being the victim of a violent crime. Nevertheless, parental structure and warmth may support the child’s ability to self regulate or provide external regulation and thereby decrease the child’s reactivity to stress. Future research using a prospective design would be necessary to evaluate these alternatives.

In sum, the present study used a developmental psychopathology framework to examine relations among autonomic functioning and contextual factors in the prospective prediction of externalizing behaviors among an inner-city sample of children. The findings support the importance of including biological variables, and autonomic functioning more specifically, when examining contextual factors that relate to externalizing behaviors. Future research that considers alternative biological processes (e.g., limbic system, prefrontal cortical) can further our understanding of relevant child × contextual interactions that affect children residing in high-risk contexts and advance our understanding of the complex processes that lead to the onset and maintenance of psychological and behavioral symptoms (Beauchaine, Neuhaus, Brenner, & Gatze-Kopp, 2008). This type of programmatic work could inform models of etiology and intervention for childhood externalizing behaviors and promote resilience among children experiencing contextual disadvantage.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from Temple University Office of the Vice President for Research and College of Liberal Arts awarded to Dr. Drabick. Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIMH 1 K01 MH073717-01A2 from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Dr. Drabick. We are particularly indebted to the families, principals, and school staff who participated in this research.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon A, Goldstein LH, Smider MJ, Kupfer DJ, Boyce WT The MacArthur Assessment Battery Working Group. Developmental and contextual influences on autonomic reactivity in young children. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;42:64–78. doi: 10.1002/dev.10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Attar BK, Guerra NG, Tolan PH. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, Mead H. Polyvagal theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from preschool to adolescence. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;74:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Hong J, Marsh P. Sex differences in autonomic correlates of conduct problems and aggression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:788–796. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef4b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Katkin ES, Strassberg Z, Snarr J. Disinhibitory psychopathology in male adolescents: Discriminating conduct disorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through concurrent assessment of multiple autonomic states. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:610–624. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Neuhaus E, Brenner SL, Gatzke-Kopp L. Ten good reasons to consider biological processes in prevention and intervention research. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:745–774. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belksy J. Differential susceptibility to rearing influence. In: Ellis BJ, Bjorklund DF, editors. Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bender HL, Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Antonishak J, Moore CM, Kelly HO, et al. Use of harsh physical discipline and developmental outcomes in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:227–242. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger TJ, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, et al. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bio-Impedance Technology, Inc (n.d.) COP-WIN (Version 6.0-H) [Computer software] Chapel Hill, NC: Author; [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Frank E, Jensen PS, Kessler RC, Nelson CA, Steinberg L The MacArthur Network on Psychopathology and Development. Social context in developmental psychopathology: Recommendations for future research from the MacArthur Network on Psychopathology and Development. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:143–164. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brofenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34:844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for development. New York: Russell Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bubier JL, Drabick DAG. Affective decision making and externalizing behaviors: The role of autonomic activity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:941–953. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, Poe MD The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Developmental psychopathology: Reactions, reflections, projections. Developmental Review. 1993;13:471–502. [Google Scholar]

- Côté SM, Vaillancourt T, Barker ED, Nagin D, Tremblay RE. Continuity and change in the joint development of physical and indirect aggression in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:37–55. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, Sylvers P, Mead H, Chipman-Chacon J. Autonomic correlates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:174–178. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DA, Beauchaine TP, Gadow KD, Carlson GA, Bromet EJ. Risk factors for conduct problems and depressive symptoms in a cohort of Ukrainian children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:244–252. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Bustamante D, Mathy RM, Miller PA, Lindholm E. Differentiation of vicariously induced emotional reactions in children. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Murphy B, Maszk P, Smith M, Karbon M. The role of emotionality and regulation in children’s social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 1995;66:1360–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Essex MJ, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context: II. Empirical explorations of an evolutionary-developmental theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:303–328. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M. Does poor vagal tone exacerbate child maladjustment in the context of parental problem drinking? A longitudinal examination. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:735–741. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Harger J, Whitson SM. Exposure to interparental conflict and children’s adjustment and physical health: The moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development. 2001;72:1617–1636. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Field TM. Individual differences in preschool entry behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1989;10:527–540. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventories manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child Symptom Inventory-4 screening and norms manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. The Symptom Inventories: An annotated bibliography [Online] Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 2006. Available: www.checkmateplus.com. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan P. The role of exposure to community violence and developmental problems among inner-city youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:101–116. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR. Relationships between parenting environment and children’s mental health among African American and European American mothers and children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:954–966. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtveen JH, Molenaar PCM. Comparison between the Fourier and Wavelet methods of spectral analysis applied to stationary and nonstationary heart period data. Psychophysiology. 2001;38(5):729–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Gottman JM. Vagal tone protects children from marital conflict. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson J, DeGarmo D, Koeppi G, Reid J. Care neglect, supervisory neglect, and harsh parenting in the development of children’s aggression: A replication and extension. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:92–107. doi: 10.1177/1077559504273684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Mayer S. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In: LE Lynn, Jr, GH McGeary., editors. Inner-city poverty in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy; 1990. pp. 111–186. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. A randomized study of neighborhood effects on low-income children’s educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:488–507. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald VM, Achenbach TM. Attention problems versus conduct problems as 6-year predictors of signs of disturbance in a national sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1254–1261. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E, Kindlon D, Earls F, Saul JP. The utility of spectral analytic techniques in the study of the autonomic regulation of beat-to-beat heart rate variability. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1994;4:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E, Tremblay RE, Kindlon D, Saul JP, Arseneault L, Seguin J, et al. Anxiety, antisocial behavior, and heart rate regulation in adolescent males. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:457–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevrokard. Long-Term Heart Rate Variability (LT-HRV) [Computer software] Ljubljana, Slovenia: Author; nd. [Google Scholar]

- Pine D, Wasserman G, Miller L, Coplan J, Bagiella E, Kovelenku P, et al. Heart period variability and psychopathology in urban boys at risk for delinquency. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:521–529. doi: 10.1017/s0048577298970846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Portales AL, Greenspan SI. Infant regulation of the vagal brake predicts child behavior problems: A psychobiological model of social behavior. Developmental Psychobiology. 1996;29:697–712. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2302(199612)29:8<697::AID-DEV5>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu M, Zhang Y, Webster JG, Tompkins WJ. Motion artifact from spot and band electrodes during impedance cardiography. Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1986;11:1029–1036. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1986.325869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Sroufe L. Developmental psychopathology: Concepts and challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:265–296. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberg MA, Shaw DS. Risk factors for boys’ conduct problems in poor and lower-middle-class neighborhoods. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:759–772. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Proctor LJ. Community violence exposure and children’s social adjustment in the school peer group: The mediating roles of emotion regulation and social cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:670–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Yoshikawa H, Roberts A, Chesir-Teran D, Allen L, Freidman JL, et al. Structural and experiential neighborhood contexts, developmental stage, and antisocial behavior among urban adolescents in poverty. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:259–281. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Correspondence among informants on parenting: Preschool children, mothers and observers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:53–68. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon KE, Beauchaine TP, Brenner SL, Neuhaus E, Gatzke-Kopp L. Familial and temperamental predictors of resilience in children at risk for conduct disorder and depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:701–727. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood A, Allen MT, Fahrenbert J, Kelsey RM, Lovallo WR, van Doornen LJP. Committee report: Methodological guidelines for impedance cardiography. Psychophysiology. 1990;27:1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Sessa FM, Morris AS, Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. Neighborhood cohesion as a buffer against hostile maternal parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:135–146. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Avenevoli S. The role of context in the development of psychopathology: A conceptual framework and some speculative propositions. Child Development. 2000;71:66–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, Nation M. Urban neighborhoods and mental health: Psychological contributions to understanding toxicity, resilience, and interventions. American Psychologist. 1998;53:647–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK, Kliewer W, Plybon L, Sica DA. Socioeconomic status and blood pressure reactivity in healthy black adolescents. Hypertension. 2000;35:496–500. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]