Abstract

Protein therapeutics may be delivered across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) by genetic fusion to a BBB molecular Trojan horse. The latter is an endogenous peptide or a peptidomimetic monoclonal antibody (MAb) against a BBB receptor, such as the insulin receptor or the transferrin receptor (TfR). Fusion proteins have been engineered with the MAb against the human insulin receptor (HIR). However, the HIRMAb is not active against the rodent insulin receptor, and cannot be used for drug delivery across the mouse BBB. The rat 8D3 MAb against the mouse TfR is active as a drug delivery system in the mouse, and the present studies describe the cloning and sequencing of the variable region of the heavy chain (VH) and light chain (VL) of the rat 8D3 TfRMAb. The VH and VL were fused to the constant region of mouse IgG1 heavy chain and mouse kappa light chain, respectively, to produce a new chimeric TfRMAb. The chimeric TfRMAb was expressed in COS cells following dual transfection with the heavy and light chain expression plasmids, and was purified by protein G affinity chromatography. The affinity of the chimeric TfRMAb for the murine TfR was equal to the 8D3 MAb using a radio-receptor assay and mouse fibroblasts. The chimeric TfRMAb was radio-labeled and injected into mice for a pharmacokinetics study of the clearance of the chimeric TfRMAb. The chimeric TfRMAb was rapidly taken up by mouse brain in vivo at a level comparable to the rat 8D3 MAb. In summary, these studies describe the genetic engineering, expression, and validation of a chimeric TfRMAb with high activity for the mouse TfR, which can be used in future engineering of therapeutic fusion proteins for BBB drug delivery in the mouse.

Keywords: blood–brain barrier, drug targeting, avidin, transferrin receptor, siRNA

Introduction

Biopharmaceuticals such as recombinant proteins, monoclonal antibodies (MAb), or short interfering RNA (siRNA) cannot be developed as drugs for the brain, because these large molecules do not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). One solution to the BBB drug delivery problem is the engineering of fusion proteins where the non-transportable protein or MAb is fused to a molecular Trojan horse (Pardridge, 2008). The latter is a genetically engineered MAb against the BBB human insulin receptor (HIR) or an MAb against the rodent transferrin receptor (TfR). The HIRMAb, or TfRMAb, undergoes receptor-mediated transport across the BBB via the endogenous transport systems for insulin or transferrin (Tf). These antibodies act as molecular Trojan horses to ferry across the BBB an attached recombinant protein that normally does not cross the BBB. The therapeutic peptide is fused to the heavy or light chain of the transporting antibody to yield a novel IgG fusion protein, as demonstrated previously for neurotrophins, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Boado et al., 2007a) or glial derived neurotrophic factor (Boado et al., 2008a), a single chain Fv antibody (Boado et al., 2007b), or a lysosomal enzyme, iduronidase (Boado et al., 2008b). For drug delivery of mono-biotinylated siRNA, an HIRMAb-avidin fusion protein has been developed (Boado et al., 2008c).

In parallel to the engineering of IgG fusion proteins for BBB drug delivery in humans, it is also necessary to develop similar fusion proteins for drug delivery in the mouse, so that preclinical investigations of fusion protein efficacy and toxicity may be examined in a rodent model. The HIRMAb is the most active molecular Trojan horse for BBB drug delivery developed to date (Pardridge, 2008). However, the HIRMAb cannot be used for drug delivery in rodents, because this antibody only cross-reacts with the insulin receptor of Old World primates, such as the Rhesus monkey. There is no known MAb against the mouse insulin receptor that can be used for BBB drug delivery in the mouse. However, the rat 8D3 MAb against the mouse TfR is rapidly transported across the mouse BBB, although this antibody is inactive in the rat (Lee et al., 2000). Therefore, the rat 8D3 TfRMAb was chosen as the model molecular Trojan horse for the engineering of mouse specific fusion proteins that cross the BBB. This first requires the initial cloning of cDNAs encoding for the variable region of the heavy chain (VH) and the variable region of the light chain (VL) of the 8D3 MAb by PCR using cDNA generated from the 8D3 rat hybridoma. In addition, it is necessary to clone cDNAs encoding for the constant (C)-region of the heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC) of the TfRMAb. The chronic administration of a rat MAb in mice could cause immune reactions. Therefore, the present investigation also describes the PCR cloning of cDNAs encoding the C-region of the mouse IgG1 heavy chain and the C-region of the mouse kappa light chain. Fusion of the rat 8D3 VH to the mouse IgG1 HC C-region, and fusion of the rat 8D3 VL to the mouse kappa LC C-region produces a rat/mouse chimeric MAb that is approximately 85% mouse amino acid sequence. The biological activity of the mouse-specific delivery system was evaluated in vitro with a cell-based mouse TfR radio-receptor binding assay, and in vivo with measurements of the pharmacokinetics and brain uptake of the radio-labeled chimeric TfRMAb. The availability of the chimeric TfRMAb will allow for future engineering and expression of murine homologues of IgG-fusion protein therapeutics for BBB drug delivery in the mouse.

Materials and Methods

PCR Cloning of 8D3 VH and VL, Mouse IgG1 Heavy Chain C-Region Region, and Mouse Kappa Light Chain C-Region Region

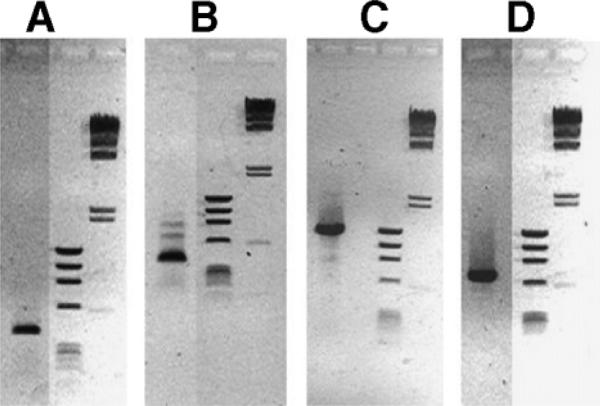

cDNA was produced by reverse transcription of hybridoma generated RNA as described previously (Li et al., 1999). RNA was isolated from two different hybridomas: the rat hybridoma producing the 8D3 MAb and a mouse hybridoma producing a MAb comprised of a mouse IgG1 (mIgG1) heavy chain (HC) and a mouse kappa (mKappa) light chain (LC). The cDNAs corresponding to the four genes were cloned by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the forward and reverse oligodexoynucleotide (ODN) primers (0.2 μM) described in Table I, 25 ng polyA + RNA-derived cDNA, 0.2 mM deoxynucleosidetriphosphates, and 2.5 U PfuUltra DNA polymerase (Stratagene, San Diego, CA) in a 50 μL Pfu buffer (Stratagene). The amplification was performed in a Mastercycler temperature cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with an initial denaturing step of 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of denaturing at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s and amplification at 72°C for 2 min; followed by a final incubation at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were resolved with 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. A single PCR product was isolated for all four genes. An 0.4 kb cDNA was isolated for the 8D3 VH (Fig. 1A); an 0.4 kb cDNA was isolated for 8D3 VL (Fig. 1B); a 1.4 kb cDNA was isolated for the mouse IgG1 HC C-region (Fig. 1C); and a 0.7 kb cDNA was isolated for the mouse κ LC C-region (Fig. 1D). These four cDNAs were subcloned into the pCR-Script plasmid (Stratagene) and subjected to DNA sequence analysis, which allowed for deduced amino acid sequences.

Table I.

PCR primers for cloning 8D3 VH and VL regions, and mouse IgG1 heavy chain C-region and mouse kappa light chain C-region.

| 8D3 VH |

| Forward: 5′-ATCCTCGAGGTTAACTGGTGGAGTCTGGAGGAGG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GGGGGTGTCGTTTTAGCTGAGGAGACAGTG-3′ |

| 8D3 VL |

| Forward: 5′-GGTGATATCGT(G/T)CTCAC(C/T)CA(A/G)TCTCCAGCAAT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GGGAAGATGGATCCAGTTGGTGCAGCATCAGC-3′ |

| Mouse IgG1 |

| Forward: 5′-CAGCCGGCCATGGCGCAGGTSCAGCTGCAGSAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCATTTACCAGGAGAGTGGGAGAG-3′ |

| Mouse kappa |

| Forward: 5′-AATTTTCAGAAGCACGCGTAGATATCKTGMTSACCCAAWCTCCA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCAACACTCTCCCCTGTTGAAGCTC-3′ |

Figure 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining of PCR cloning of 0.4 kb TfRMAb VH (A), 0.4 kb TfRMAb VL (B), 1.4 kb mouse IgG1 C-region (C), and 0.7 kb mouse kappa C-region (D). The PCR generated cDNA is shown in lane 1, and DNA size standards are shown in lanes 2 and 3 for each panel.

Amino Acid Micro-Sequencing of 8D3 Heavy and Light Chains

The amino terminal amino acid sequences of the 8D3 heavy chain and light chain were determined to (a) confirm isolation of the correct cDNAs encoding the VH and VL, and (b) identify any errors in the amino terminal sequences caused by degeneracy in the PCR primers (Table I). The 8D3 hybridoma was cultured, and the 8D3 MAb was purified by protein G affinity chromatography. The 8D3 MAb was applied to a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) followed by blotting to a PVDF filter and amino acid microsequencing analysis at the amino terminus was performed at the Caltech Protein/Peptide MicroAnalytical Laboratory (Pasadena, CA). The HC was sequenced through the first 11 amino acids and the LC was sequenced through the first 21 amino acids. This N-terminal amino acid microsequence data matched with the predicted amino acid sequence derived from the cloning of the 8D3 VH and 8D3 VL genes, and revealed PCR-induced errors in the amino terminal amino acid sequence in both the VH and VL. In engineering of the expression plasmids described below, custom PCR primers were design to introduce a V3Q and L4M change in the VL and a Q5V change in the VH sequence. Apart from these PCR-induced changes, there was a 100% match in amino acid identity between the predicted and observed amino acid sequence of the 8D3 HC and LC amino termini.

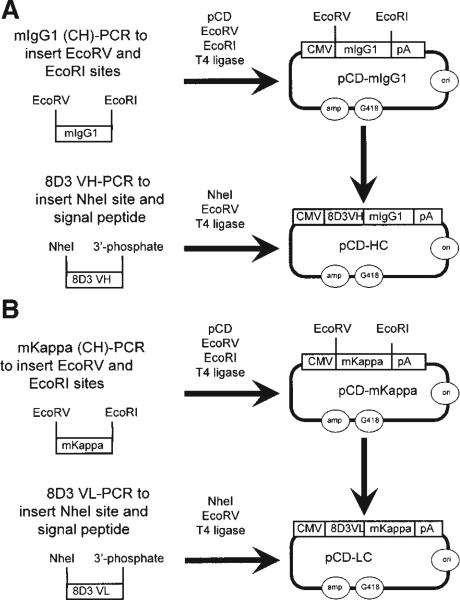

Engineering of Chimeric TfRMAb Expression Plasmid DNAs

The engineering of the chimeric TfRMAb (cTfRMAb) HC expression plasmid was completed as outlined in Figure 2A. The mIgG1 C-region cDNA was generated by PCR using the pCR-Script described above as template, and to introduce both EcoRV and EcoRI sites at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The mIgG1 C-region cDNA was inserted at the same restriction endonuclease site of the expression plasmid pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to form the intermediate plasmid pCD-mIgG1 (Fig. 2A). The engineering of the cTfRMAb HC expression plasmid was then completed by insertion of the 8D3 VH cDNA into the NheI and EcoRV sites of pCD-mIgG1 to form pCD-HC (Fig. 2A). The 8D3 VH cDNA was generated by PCR and it has both an NheI site and the signal peptide sequence on the 5′-end. The 3′-end of the PCR generated 8D3 VH was phosphorylated for ligation into the EcoRV site of pCD-mIgG1.

Figure 2.

Genetic engineering of the eukaryotic heavy chain (HC) expression plasmid, pCD-HC and the light chain (LC) expression plasmid, pCD-LC, is shown in Panels A and B, respectively. The variable region of the HC (VH) of the chimeric TfRMAb is fused to the C-region of mouse IgG1 (mIgG1) in pCD-HC, and the variable region of the LC (VL) of the chimeric TfRMAb is fused to the C-region of mouse kappa (mKappa) in pCD-LC.

The engineering of the cTfRMAb LC expression plasmid was completed as outlined in Figure 2B. The C-region of the mouse kappa (mKappa) cDNA was generated by PCR using the pCR-Script described above as template, and to introduce both EcoRV and EcoRI sites at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The mKappa constant C-region cDNA was inserted at the same restriction endonuclease site of the expression plasmid pcDNA3.1 to form the intermediate plasmid pCD-mKappa (Fig. 2B). The engineering of the cTfRMAb LC expression plasmid was then completed by insertion of the 8D3 VL cDNA into the NheI and EcoRV sites of pCD-mKappa to form pCD-LC (Fig. 2B). The 8D3 VL cDNA was generated by PCR and it has both an NheI site and a signal peptide sequence on the 5′-end. The 3′-end of the PCR generated 8D3 VL was phosphorylated for ligation into the EcoRV site of pCD-mKappa. All intermediate plasmids were treated with alkaline phosphatase to prevent self-ligation. Constructs were subjected to nucleotide sequence analysis in both directions, as described previously (Boado et al., 2007a).

Transient Expression of Chimeric TfRMAb in COS Cells

COS cells were dual transfected with pCD-LC and pCD-HC using Lipofectamine 2000, with a ratio of 1:2.5 μg DNA:μL Lipofectamine. Following transfection, the cells were cultured in serum free VP-SFM (Invitrogen). The conditioned serum free medium was collected at 3 and 7 days. The cTfRMAb, which contained the mouse IgG1 C-region, was purified by affinity chromatography with a 5 mL column of protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Mouse IgG-Specific ELISA and Western Blot

The secretion of the cTfRMAb into the SFM was detected with a mouse IgG-specific ELISA. The primary antibody was a goat anti-mouse IgG1 Fc region antibody (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), which was plated at 0.4 μg/well in 96-well plates. The binding of the cTfRMAb to the primary antibody was detected with a conjugate of alkaline phosphatase and a goat anti-mouse LC kappa antibody (Bethyl Laboratories). Mouse IgG1/kappa IgG (M7894, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as the assay standard. The cTfRMAb was detected by Western blotting following reducing 12% SDS–PAGE and blotting to nitrocellulose. The primary antibody was a goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (Bethyl Laboratories) and the secondary antibody was a biotinylated horse anti-goat IgG (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA).

Mouse TfR Radio-Receptor Assay

Mouse fibroblasts were plated in 24-well cluster dishes (100,000 cells/well) 24 h before the radio-receptor assay (RRA) of TfRMAb binding to the mouse TfR. The medium was aspirated, the cells washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and 500 μL was added to each well containing 0.15 μCi/mL of [125I]-labeled rat 8D3 MAb, and 0.3−100 nM concentrations of either unlabeled rat 8D3 MAb or unlabeled cTfRMAb. Following incubation at 4°C for 120 min, the medium was aspirated, the plates washed with cold PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and the monolayer was lysed with 0.2 mL/well of 1 N NaOH. An aliquot was removed for protein measurement using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), and the radioactivity in the lysate was determined with a Beckmann gamma counter. The % bound/mg protein was computed from the radioactivity in the cell lysate and the total radioactivity in the medium. The 8D3 self-inhibition binding data were fit by nonlinear regression analysis to:

where Bt is the total binding, Bmax is the maximal binding, KD is the dissociation constant, S is the MAb concentration, and NSB is the non-saturable binding. The cTfRMAb cross-inhibition binding data were fit by nonlinear regression analysis to:

where I is the cTfRMAb concentration, and KI is the cTfRMAb inhibitor constant.

Antibody Iodination

The protein G-purified hybridoma-generated rat 8D3 MAb or the COS lipofected-generated cTfRMAb was radiolabeled with 125-iodine and chloramine T, followed by purification with a 0.7 cm × 25 cm column of Sephadex G25 and elution in PBS with 0.1% BSA. The specific activity was 4.3 μCi/ug for the rat 8D3 MAb and 33 μCi/ug for the cTfRMAb, and both proteins were >99% precipitated with cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA).

In Vivo Pharmacokinetics and Organ Uptake of [125I]-cTfRMAb in the Mouse

Adult male BALB/c mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and injected intravenously with 5 μCi/mouse of [125I]-cTfRMAb. Blood was sampled from the common carotid artery at 0.5, 2, 5, 15, and 60 min, and the mouse was euthanized at 60 min for removal of brain, liver, kidney, and heart. The radioactivity was determined in the organ, CPM/g, and in plasma, CPM/μL. Samples of plasma were analyzed by TCA precipitation. The organ volume of distribution (VD) was computed from the ratio of CPM/g to CPM/μL of 60 min organ and plasma radioactivity, respectively. The plasma radioactivity, A(t), was expressed as a % of injected dose (ID)/mL, and was fit to a 2 exponential equation:

where An and kn are the intercepts and slopes of the exponential decay. The pharmacokinetics parameters were calculated from A1, A2, k1, and k2, as described previously (Lee et al., 2000). The derivative-free nonlinear regression analysis used subroutine PAR of the BMDP Statistical Software, where the A(t) data were weighted according to 1/[A(t)]2. The data were fit to both a single and dual exponential decay curve and the residual sum of squares was lowest with the dual exponential function.

Results

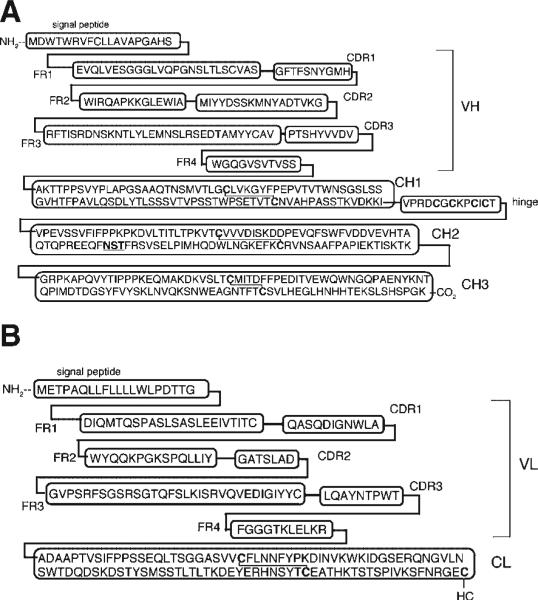

DNA sequence analysis of the chimeric heavy chain expression plasmid, pCD-HC (Fig. 2A), showed the expression cassette was comprised of 2,501 nucleotides (nt), which included a 714 nt cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, a 9 nt Kozak sequence (GCCGCCACC), a 1,386 nt open reading frame, and a 392 nt BGH polyA (pA) region. The open reading frame encoded for a 461 amino acid (AA) heavy chain, which included a 19 AA signal peptide, a 118 AA VH region, and a 324 AA mouse IgG1 C-region, as shown in Figure 3A. The predicted molecular weight of the non-glycosylated heavy chain is 48,824 Da with an isoelectric point (pI) of 6.29. DNA sequence analysis of the chimeric light chain expression plasmid, pCD-LC (Fig. 2B), showed the expression cassette was comprised of 1,839 nucleotides (nt), which included a 731 nt CMV promoter, a 9 nt Kozak sequence, a 705 nt open reading frame, and a 394 nt BGH pA region. The open reading frame encoded for a 234 AA light chain, which included a 20 AA signal peptide, a 108 AA VL region, and a 106 AA mouse kappa C-region, as shown in Figure 3B. The predicted molecular weight of the light chain is 23,554 Da with a pI of 5.73.

Figure 3.

Deduced amino acid sequence of the chimeric TfRMAb heavy chain (A) and light chain (B). The individual complementarity determining regions (CDR) and framework regions (FR) of the VH and VL are shown. The HC C-region is comprised of four sub-domains: CH1, hinge, CH2, and CH3. The LC C-region is denoted as CL.

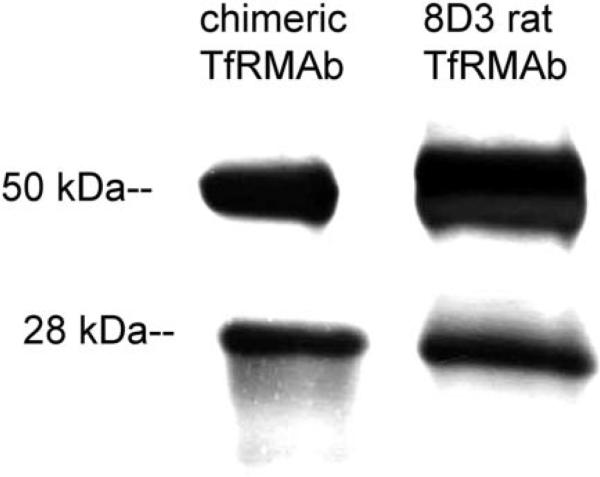

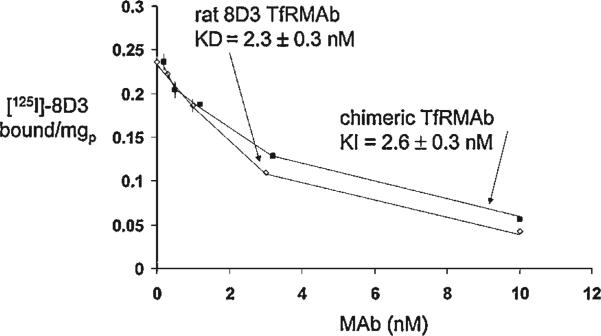

Dual transfection with the pCD-HC and pCD-LC expression plasmids of COS cells grown in 6-well cluster dishes resulted in the secretion of mouse IgG into serum free medium (SFM) as determined with a mouse IgG specific ELISA (see Materials and Methods Section). Mouse IgG in SFM conditioned by COS cells exposed only to Lipofectamine 2000 was not detectable. The mouse IgG level in SFM conditioned by COS cells dual transfected with the heavy and light chain expression plasmids was 677 ± 40 and 1,278 ± 111 ng/mL at 3 and 7 days after lipofection, respectively. For production of larger amounts of the chimeric TfRMAb, COS cells were plated on 10 × T 500 flasks and dual transfected with the heavy chain and light chain expression plasmids. The 3−7-day conditioned medium was concentrated to 400 mL with tangential flow filtration, and the chimeric TfRMAb was affinity purified with protein G chromatography. SDS–PAGE and Coomasie blue staining showed the protein was purified to homogeneity. Western blot analysis showed the size of the immunoreactive heavy and light chains of the chimeric TfRMAb and the 8D3 rat TfRMAb were comparable (Fig. 4). The relative affinity for the mouse TfR of the chimeric TfRMAb and the 8D3 rat TfRMAb was evaluated with a radio-receptor assay using mouse fibroblasts as the source of the mouse TfR and [125I]-8D3 MAb as the receptor ligand. Unlabeled concentrations of either the 8D3 rat TfRMAb or the chimeric TfRMAb caused displacement of the [125I]-8D3 MAb from the TfR. Nonlinear regression analysis (see Materials and Methods Section) of the binding isotherms in Figure 5 showed the KD of 8D3 binding to the mouse TfR was 2.3 ± 0.3 nM with a Bmax of 0.32 ± 0.02 pmol/mg protein, and a non-specific binding (NSB) of 2.9 ± 0.2 μL/mg protein. The KI of the cTfRMAb inhibition of [125I]-8D3 TfRMAb binding to the rat TfR was 2.6 ± 0.3 nM (Fig. 5), which is not significantly different from the KD of rat 8D3 binding to the mouse TfR.

Figure 4.

Western blot shows identical reactivity with an anti-mouse antibody of the chimeric TfRMAb (lane 1) and the 8D3 rat hybridoma-generated TfRMAb (lane 2).

Figure 5.

Radio-receptor assay of the mouse TfR uses mouse fibroblasts as the source of the mouse TfR and [125I]-8D3 as the binding ligand. Binding is displaced by unlabeled 8D3 MAb or the chimeric TfRMAb. The KD of 8D3 self-inhibition and the KI of chimeric TfRMAb cross-inhibition were computed by nonlinear regression analysis (see Materials and Methods Section).

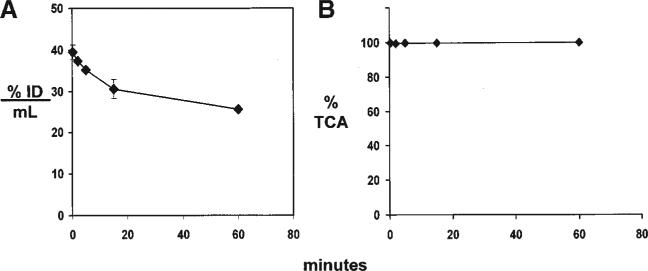

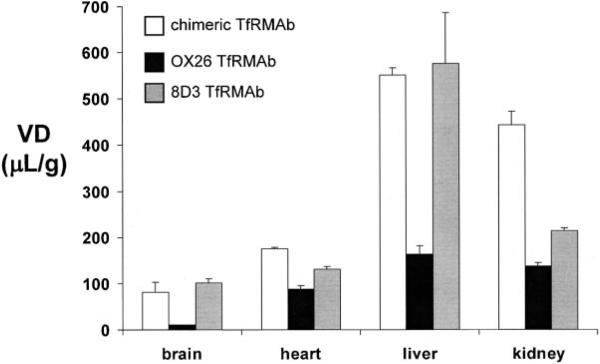

The binding of the cTfRMAb to the mouse TfR in vivo was examined with the in vivo pharmacokinetics and organ uptake of the [125I]-cTfRMAb in the adult mouse. The [125I]-cTfRMAb was cleared from blood at the rate shown in Figure 6A. The [125I]-cTfRMAb was highly stable in vivo as the plasma radioactivity that was TCA-precipitable was >99% in both the pre-injection sample and the 60 min plasma sample (Fig. 6B). The plasma decay curve (Fig. 6A) was subjected to a pharmacokinetics (PK) analysis using a bi-exponential model (see Materials and Methods Section) and the intercepts and slopes are given in Table II. The calculated PK parameters, including the mean residence time (MRT), the initial volume of distribution (Vc), the steady state volume of distribution (Vss), the area under the concentration curve (AUC) at 60 min [AUC(60 min)] and at steady state (AUCss), and the plasma clearance (Cl) were computed and are given in Table II. The 60 min organ uptake of the [125I]-cTfRMAb, expressed as a volume of distribution (VD), was measured for brain, liver, kidney, and heart, and these values are given in Figure 7, in comparison with previously reported VD values in the mouse for the [125I]-8D3 TfRMAb, and the [125I]-OX26 TfRMAb (Lee et al., 2000).

Figure 6.

A: Plasma concentration of [125I]-cTfRMAb in the mouse is expressed as % of injected dose (ID)/mL, and is plotted versus time after a single intravenous injection in the anesthetized mouse. B: Plasma radioactivity that is precipitable by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) is plotted versus time after intravenous injection. Data are mean ± SE (n = 3 mice per time point). Some error bars are too small to be visible.

Table II.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of chimeric TfRMAb in the mouse.

| Parameter | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | %ID/mL | 18.4 ± 4.2 |

| A2 | %ID/mL | 33.9 ± 2.1 |

| k1 | min−1 | 0.71 ± 0.37 |

| k2 | min−1 | 0.0048 ± 0.0016 |

| min | 0.98 ± 0.51 | |

| min | 144 ± 48 | |

| MRT | min | 208 ± 68 |

| Vc | mL/kg | 64 ± 5 |

| Vss | mL/kg | 97 ± 6 |

| AUC(60 min) | %ID min/mL | 1794 ± 60 |

| AUCss | %ID min/mL | 7098 ± 2010 |

| Cl | mL/min/kg | 0.47 ± 0.13 |

MRT, mean residence time; Vc, plasma volume; Vss, steady state volume of distribution; AUC(60 min), area under the curve first 60 min; AUCss, steady state AUC; Cl, clearance from plasma.

Figure 7.

The organ volume of distribution (VD) in the mouse at 60 min after intravenous injection is shown for brain, heart, liver, and kidney for the [125I]-cTfRMAb (open bars), the [125I]-OX26 TfRMAb (solid bars), and the [125I]-8D3 TfRMAb (gray bars). The VD data for the [125I]-OX26 TfRMAb and the [125I]-8D3 TfRMAb are from Lee et al. (2000). Data are mean ± SE (n = 3 mice per time point). Some error bars are too small to be visible.

Discussion

The results of this investigation are consistent with the following conclusions. First, the PCR cloning is described for the rat 8D3 TfRMAb VH and VL, the mouse IgG1 C-region, and mouse kappa C-region (Fig. 1), and the amino acid sequence predicted from DNA sequence analysis (Fig. 3) matches the amino acid sequence determined from either direct amino acid micro-sequencing of the antibody heavy and light chains, in the case of the 8D3 VH and VL (see Materials and Methods Section), or the known amino acid sequence of the mouse IgG1 C-region (GenBank U65534) or mouse kappa C-region (GenBank Z37499). Second, eukaryotic expression plasmids have been engineered for dual expression of the cTfRMAb HC and LC (Fig. 2), which results in expression and secretion of the cTfRMAb, as determined by a mouse IgG ELISA (see Materials and Methods Section) and Western blotting (Fig. 4). Third, the binding affinity at the mouse TfR for the cTfRMAb is comparable to the affinity of the hybridoma generated rat 8D3 TfRMAb, as determined with a radio-receptor assay and mouse fibroblasts as the source of the murine TfR (Fig. 5). Comparable activity between the cTfRMAb and the rat 8D3 TfRMAb is also demonstrated by the parallel organ uptake in the mouse in vivo (Fig. 7). Fourth, the cTfRMAb is rapidly cleared by TfR-rich organs in vivo (Figs. 6A and 7), and is stable in vivo with a TCA precipitation >99% in mouse plasma at 60 min after injection (Fig. 6B). Fifth, comparison of the amino acid sequence of the VH and VL of the rat 8D3 MAb to the mouse TfR with the amino acid sequence of the VH and VL of the murine OX26 to the rat TfR shows minimal conservation in the CDRs, but significant conservation in the FRs (Table III).

Table III.

Comparison of amino acid sequences in VH and VL of rat 8D3 and mouse OX26 antibodies.

| Chain | CDR1 | CDR2 | CDR3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8D3 heavy chain | GFTFSNYGMH | MIYYDSSKMNYADTVKG | PTSHYVVDV |

| OX26 heavy chain | GYSFTTYWMN | MIHPSDSEVRLNQKFKD | FGLDY |

| 8D3 light chain | QASQDIGNWLA | GATSLAD | LQAYNTPWT |

| OX26 light chain | HASQNINVWLS | KASNLHT | QQGQSYPWT |

| Chain | FR1 | FR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8D3 heavy chain | EVQLVESGGGLVQPGNSLTLSCVAS | WIRQAPKKGLEWIA | |

| OX26 heavy chain | QVQLQQPGAALVRPGASMRLSCKAS | WVKQRPGQGLELIG | |

| 8D3 light chain | DIQMTQSPASLSASLEEIVTITC | WYQQKPGKSPQLLIY | |

| OX26 light chain | DIVITQSPSSLSASLGDTILITC | WFQQKPGNAPKLLIY | |

| Chain | FR3 | FR4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8D3 heavy chain | RFTISRDNSKNTLYLEMNSLRSEDTAMYYCAV | WGQGVSVTVSS | |

| OX26 heavy chain | KATLTVDTSSSTAYMQLNSPTSEDSAVYYCAR | WGQGTTLTVSS | |

| 8D3 light chain | GVPSRFSGSRSGTQFSLKISRVQVEDIGIYYC | FGGGTKLELKR | |

| OX26 light chain | GVPSRFSGSGSGTGFTLTISSLQPEDIATYYC | FGGGTKLEIKR | |

The amino acid sequence for the murine OX26 MAb against the rat TfR is from Li et al. (1999). Underlined sequences show amino acid identity.

The 8D3 rat MAb against the mouse TfR is the most potent BBB Trojan horse developed to date for drug delivery across the mouse BBB (Lee et al., 2000). Following the cloning of the VH and VL of the 8D3 MAb, it is possible to genetically engineer fusion proteins for delivery of protein therapeutics to the mouse brain, similar to fusion proteins recently engineered for the human brain (Pardridge, 2008). The 8D3 VH and VL must be fused to the C-region. The intent is to administer the fusion proteins to mice on a chronic basis. Therefore, in the present study, the C-region of mouse IgG1 heavy chain, and the C-region of mouse kappa light chain, were PCR cloned (Figs. 1 and 2). The use of mouse C-region results in the production of a mouse/rat chimeric TfRMAb, which is approximately 85% mouse amino acid sequence. The mouse kappa C-region was chosen for the LC isotype, because the 8D3 MAb light chain is a rat kappa isotype (unpublished observations). The mouse IgG1 C-region was chosen for the HC isotype, because the mouse IgG1 hinge region exhibits the least flexibility of the mouse IgG heavy chain isotypes (Dangl et al., 1988). The more rigid hinge region may result in reduced protease cleavage of the hinge region, which may be advantageous for certain fusion proteins. Alternatively, a greater degree of segmental flexibility may be required for certain fusion proteins, and this is provided by the use of the C-region of the mouse IgG2a or IgG2b isotype (Dangl et al., 1988; Schneider et al., 1988). The use of the mouse IgG1 HC and mouse kappa LC C-regions resulted in no loss in affinity of the chimeric TfRMAb for the mouse TfR, as compared to the original rat 8D3 MAb (Fig. 5).

The pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters in vivo of the chimeric TfRMAb (Table II) replicate the PK parameters of the rat 8D3 MAb in vivo reportedly previously in the mouse (Lee et al., 2000). In both instances, the sampling time was limited to 0−60 min, which is shorter than either the terminal half-time of clearance or the MRT reported in Table II. Therefore, these PK parameters represent approximations. The chimeric TfRMAb is removed from plasma with a clearance rate of 0.47 ± 0.13 mL/min/kg (Table II), and this rate is comparable to the clearance of the 8D3 MAb in mice, 0.24 ± 0.03 mL/min/kg (Lee et al., 2000). The brain VD of the chimeric TfRMAb is comparable to the brain VD for the 8D3 MAb in the mouse, whereas the brain VD of the murine OX26 MAb to the rat TfR is very low in the mouse (Fig. 7). The murine OX26 MAb to the rat TfR does not recognize the mouse TfR, is not transported across the mouse BBB (Lee et al., 2000), and functions as a blood volume marker in the mouse. The blood volume in peripheral organs is much higher than in brain, which is represented by the higher VD of the OX26 MAb in mouse heart, liver, and kidney, as compared to the brain (Fig. 7). The high VD of the chimeric TfRMAb in heart is due mainly to distribution in the high blood volume in that organ, as the VD of the chimeric TfRMAb or the 8D3 TfRMAb in heart is not much higher than the OX26 MAb (Fig. 7). In contrast, the VD in liver of the chimeric TfRMAb or the 8D3 MAb is very high compared to the blood volume as represented by the VD of the OX26 MAb (Fig. 7), which indicates chimeric TfRMAb and 8D3 antibodies are selectively taken up by the liver TfR. With respect to kidney, the uptake of the chimeric TfRMAb is somewhat higher than the uptake of the 8D3 TfRMAb (Fig. 7). The data in Figure 7 could also be reported as a % ID/g organ, as reported previously for the rat 8D3 MAb in the mouse (Lee et al., 2000). Since, the organ VD values for the chimeric TfRMAb and the rat 8D3 MAb are nearly comparable (Fig. 7), and the plasma AUC values are nearly equal, the organ uptake of the chimeric TfRMAb, as measured by % ID/g, is comparable to that reported previously for the rat 8D3 MAb (Lee et al., 2000).

The TfR is expressed by two different genes, encoding either the TfR1 or the TfR2 (Kawabata et al., 2001). The 8D3 MAb is directed against the TfR1, as demonstrated by amino acid alignment of peptide sequences of the 8D3 antigen with the mouse TfR (Kissel et al., 1998), and these peptide sequences are found in the mouse TfR1 (GenBank NP_035768), not the mouse TfR2 (GenBank NP_056614). The specificity of the 8D3 MAb for the TfR1, and the high rate of transport of the 8D3 MAb across the mouse BBB (Lee et al., 2000), are both consistent with results of BBB genomics investigations. BBB gene micro-array studies in the rat show the TfR1 (GenBank M58040) is highly expressed at the BBB, but is not expressed in liver (Li et al., 2001). In contrast, the principal hepatic TfR is TfR2 (Kawabata et al., 2001). The high activity of either the chimeric TfRMAb or the 8D3 TfRMAb in mouse liver (Fig. 7) suggests the epitope within the TfR1 that is recognized by the 8D3 MAb is conserved in the TfR2. Blast2 alignment of the amino acid sequences of the mouse TfR1 (GenBank NP_035768) and the mouse TfR2 (GenBank NP_056614) shows there is a overall 43% amino acid identity in these two receptors.

The affinity of the chimeric TfRMAb for the TfR1 is determined by the amino acid sequence of the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) within the VH or VL of the antibody. The amino acid sequences within the framework regions (FRs) of the VH and VL also contribute to target binding. The amino acid sequences comprising the CDRs and FRs of the 8D3 VH and VL are given in Table III, and are compared with the comparable amino acid sequences for the murine OX26 MAb against the rat TfR reported previously (Li et al., 1999). There is little amino acid identity in the CDRs of these two antibodies (Table III), which is consistent with the absence of biological activity of the OX26 MAb in the mouse (Fig. 7). With respect to the FR regions of the 8D3 and OX26 antibodies, there is some amino acid conservation, as shown by the underlined sequences in Table III. The overall amino acid identity between the FR regions of the OX26 and 8D3 antibodies is 54% and 73%, respectively, for the VH and VL. The sequences shown in Table III for the OX26 MAb against the rat TfR (Li et al., 1999) can be used to engineer a chimeric MAb against the rat TfR for drug delivery across the rat BBB in vivo.

In summary, these studies describe the cloning of the VH and VL of the rat 8D3 MAb against the mouse TfR, and the expression of a chimeric TfRMAb against the mouse TfR, that is derived from the VH and VL of the rat 8D3 IgG, and which is 85% mouse sequence (Fig. 3). The chimeric TfRMAb has high affinity for the mouse TfR (Fig. 5), and is actively transported into mouse brain in vivo (Fig. 7). The genes encoding the HC and LC of the chimeric TfRMAb may be used in future studies on the engineering of therapeutic fusion proteins that are biologically active in the mouse. In addition, chimeric TfRMAb/avidin fusion proteins may be engineered for the BBB delivery of mono-biotinylated drugs, including biotinylated siRNA for in vivo RNA interference.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R43-NS-062458 and R01-AG-032244. The authors are indebted to Winnie Tai and Phuong Tram for valuable technical assistance.

Contract grant sponsor: NIH

Contract grant numbers: R43-NS-062458; R01-AG-032244

References

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Genetic engineering, expression, and activity of a fusion protein of a human neurotrophin and a molecular Trojan horse for delivery across the human blood-brain barrier. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007a;97:1376–1386. doi: 10.1002/bit.21369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xia CF, Pardridge WM. Fusion antibody for Alzheimer's disease with bidirectional transport across the blood-brain barrier and abeta fibril disaggregation. Bioconjug Chem. 2007b;18:447–455. doi: 10.1021/bc060349x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Pardridge WM. GDNF fusion protein for targeted-drug delivery across the human blood-brain barrier. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008a;100:387–986. doi: 10.1002/bit.21764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xia CF, Wang Y, Pardridge WM. Genetic engineering of a lysosomal enzyme fusion protein for targeted delivery across the human blood-brain barrier. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2008b;99:475–484. doi: 10.1002/bit.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Xia CF, Wang Y, Pardridge WM. Genetic engineering, expression, and activity of a chimeric monoclonal antibody-avidin fusion protein for receptor-mediated delivery of biotinylated drugs in humans. Bioconjug Chem. 2008c;19:731–739. doi: 10.1021/bc7004076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Wensel TG, Morrison SL, Stryer L, Herzenberg LA, Oi VT. Segmental flexibility and complement fixation of genetically engineered chimeric human, rabbit and mouse antibodies. EMBO J. 1988;7:1989–1994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata H, Germain RS, Ikezoe T, Tong X, Green EM, Gombart AF, Koeffler HP. Regulation of expression of murine transferrin receptor 2. Blood. 2001;98:1949–1954. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissel K, Hamm S, Schulz M, Vecchi A, Garlanda C, Engelhardt B. Immunohistochemical localization of the murine transferrin receptor (TfR) on blood-tissue barriers using a novel anti-TfR monoclonal antibody. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;110:64–72. doi: 10.1007/s004180050266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Engelhardt B, Lesley J, Bickel U, Pardridge WM. Targeting rat anti-mouse transferrin receptor monoclonal antibodies through the blood-brain barrier in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:1048–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Sugimura K, Boado RJ, Lee HJ, Zhang C, Dubel S, Pardridge WM. Genetically engineered brain drug delivery vectors—Cloning, expression, and in vivo application of an anti-transferrin receptor single chain antibody-streptavidin fusion gene and protein. Prot Engineer. 1999;12:787–796. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.9.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier genomics. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol. 2001;21:61–68. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. Re-engineering protein pharmaceuticals for delivery to brain with molecular Trojan horses. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1327–1338. doi: 10.1021/bc800148t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider WP, Wensel TG, Stryer L, Oi VT. Genetically engineered immunoglobulins reveal structural features controlling segmental flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2509–2513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]