Summary

Oncogenic alterations that confer proliferative advantages in epithelial tissues also often trigger apoptosis, suggesting an evolutionary mechanism by which organisms eliminate aberrant cells from epithelia. However, the underlying mechanism of how these tissues eliminate oncogenic cells remains to be elucidated. In Drosophila imaginal epithelia, clones of cells mutant for evolutionarily conserved tumor suppressors, such as scrib or dlg, lose their epithelial integrity and are eliminated by JNK-dependent cell death. Here, we show that Eiger, a Drosophila member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily, behaves like a tumor suppressor that eliminates oncogenic mutant cells from epithelia. In the absence of Eiger, these mutant clones are no longer eliminated; instead, they grow aggressively and develop into tumors. Our analysis shows that Eiger is translocated to endocytic vesicles in scrib mutant clones, which leads to activation of apoptotic Eiger-JNK signaling in endosomes. Furthermore, we show that Eiger’s tumor suppressor-like function is dependent on its endocytosis, as blocking endocytosis prevents both JNK activation and elimination of these clones. Our data indicate that TNF signaling and the endocytic machinary could be components of an evolutionarily conserved fail-safe mechanism by which animals maintain epithelial integrity to protect against neoplastic development.

Introduction

Tumorigenesis in humans requires multiple genetic alterations (Kinzler and Vogelstein, 1996). A given oncogenic mutation often stimulates both proliferative and apoptotic programs, suggesting that evolution has installed an intrinsic tumor suppression mechanism within the proliferative machinery (Lowe et al., 2004). For instance, many oncogenic alterations or damages lead to activation of the p53 tumor suppressor, which can induce apoptosis in these cells, thereby eliminating cells with deleterious alterations from the tissue. Thus, context-dependent activation of a cell-death signaling could serve as an important tumor suppressor mechanism in multicellular organisms.

Most human cancers originate from epithelial tissues. In these tissues, loss of epithelial integrity, particularly its apicobasal polarity, is often associated with tumor development and malignancy (Bissell and Radisky, 2001; Fish and Molitoris, 1994). It is therefore crucial for animals to maintain epithelial integrity to protect themselves from neoplastic development. One of the important strategies for maintaining epithelial integrity is to actively eliminate these aberrant cells from the tissue. However, the underlying mechanism of how epithelial tissue eliminates oncogenic cells remains to be elucidated.

In Drosophila, clones of cells mutant for evolutionarily conserved tumor suppressor genes such as scribble (scrib), discs large (dlg), and lethal giant larvae (lgl), which encode proteins essential for establishing epithelial apicobasal polarity (Bilder, 2004; Hariharan and Bilder, 2006; Tepass et al., 2001), are eliminated by apoptosis from the imaginal epithelia (Agrawal et al., 1995; Brumby and Richardson, 2003; Igaki et al., 2006; Pagliarini and Xu, 2003; Woods and Bryant, 1991). This implicates that imaginal epithelia also have an intrinsic “fail-safe” system to eliminate tumorigenic polarity-deficient cells. The elimination of polarity-deficient cells such as those mutant for scrib is JNK-dependent (Brumby and Richardson, 2003; Igaki et al., 2006; Uhlirova et al., 2005). However, the mechanism of how this cell-elimination pathway is activated is unknown.

Drosophila has a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily, Eiger (Igaki et al., 2002; Moreno et al., 2002). It has been suggested that Eiger is a ligand for the Drosophila JNK pathway, as its overexpression induces JNK-dependent cell death in imaginal epithelia (Igaki et al., 2002; Moreno et al., 2002). However, eiger loss-of-function mutants show no morphological or cell death defect during normal development (Igaki et al., 2002). Thus, the physiological role of Eiger remains unknown. Here, we show that Eiger behaves like a tumor suppressor that eliminates cells with oncogenic mutations, thereby maintaining epithelial integrity. Furthermore, we show that endocytosis plays an essential role in this tumor suppression mechanism.

Results

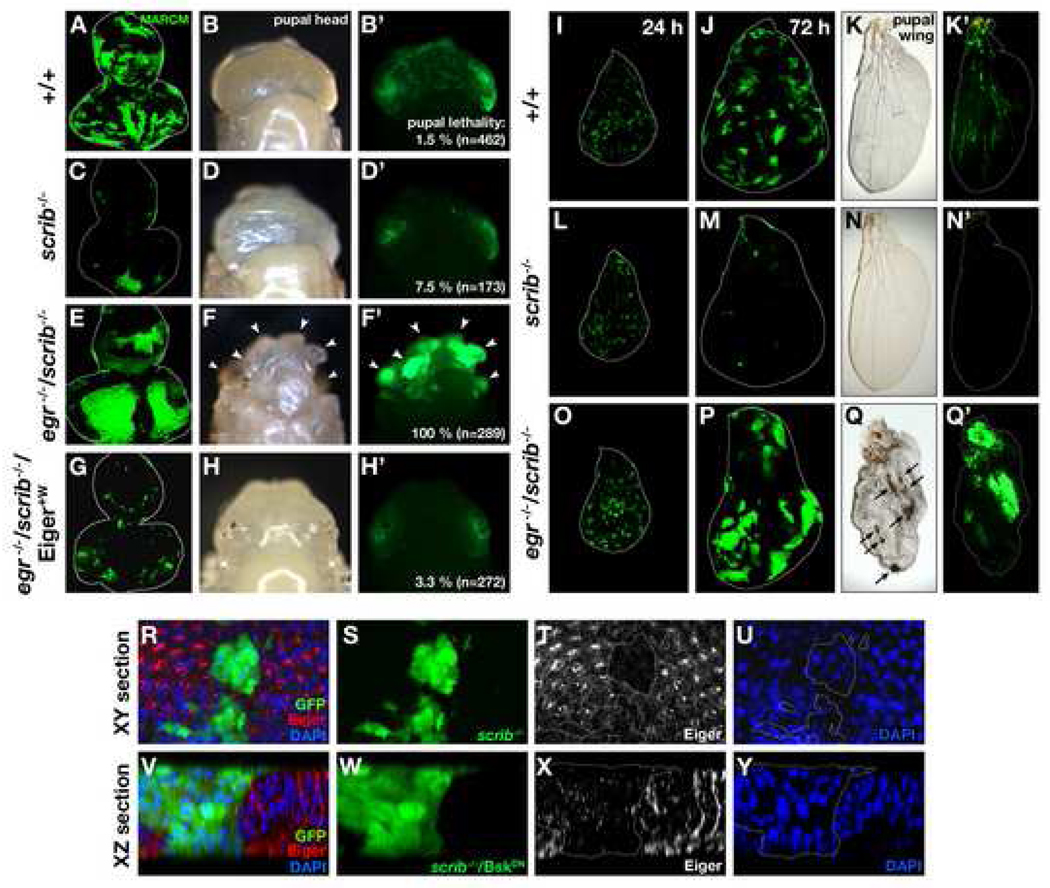

Imaginal epithelia eliminate scrib mutant clones through Eiger

Clones of scrib mutant cells generated in otherwise wild-type imaginal epithelia are eliminated by JNK-dependent cell death (Brumby and Richardson, 2003; Igaki et al., 2006; Pagliarini and Xu, 2003; Uhlirova et al., 2005) (Figures 1A-1D’and 1I-1N’). To study the mechanism of this cell elimination, we examined the possible role of Eiger in this process. Eiger is the Drosophila TNF superfamily member that can trigger JNK-dependent cell death; however, eiger mutant flies have no defect in developmental cell death (Igaki et al., 2002). It is therefore possible that, like p53, Eiger is latent in normal situation but is activated when tissue needs to eliminate damaged or harmful cells. To test this possibility, we produced scrib mutant clones in eiger mutant eye-antennal discs. Strikingly, in this background, scrib clones were no longer eliminated; instead, these clones grew aggressively and developed into tumors (Figures 1E–1F’). DAPI staining confirmed that these tumors are indeed masses of overproliferating cells (data not shown). Animals carrying these tumors died as pupae (100% penetrance, n=289; Figure 1F’). This tumorigenesis phenotype could not be caused by simply blocking caspase-dependent cell death, as scrib mutant clones overexpressing p35 did not develop into tumors and the animals with these clones survived into adulthood (Brumby and Richardson, 2003). On the contrary, overexpression of a dominant-negative form of JNK (BskDN) in scrib clones recapitulated the tumorigenesis phenotype (data not shown) (Brumby and Richardson, 2003), suggesting that scrib clones may result in JNK-dependent and caspase-independent cell death. We also observed the same tumorigenesis phenotype in wing discs (Figures 1O–1Q’), which suggests the phenomenon is not organ-specific. The wing disc with wild-type eiger gene completely eliminated scrib clones by adulthood and perfectly maintained tissue integrity (Figures 1N and 1N’), while the wing disc deficient for eiger gene did not eliminate these mutant clones and allowed them to develop tumors (Figures 1Q and 1Q’). Similar results were also obtained when another tumor suppressor mutant, dlg, was substituted for scrib (data not shown), indicating that this phenotype is common to these apicobasal polarity mutations. We found that both tumor formation and animal lethality were completely rescued by introducing a wild-type eiger transgene (Eiger+W) (Igaki et al., 2006) within eiger/scrib double-mutant clones (Figures 1G–1H’), indicating that Eiger expression is sufficient for scrib clones to be eliminated. Importantly, this transgene is weaker than other UAS-Eiger transgenes and causes no morphological defect when it is expressed in the eye by the GMR-Gal4 driver (Figures 4I, 4J, and Supplemental Fig. S1) (Igaki et al., 2002; Moreno et al., 2002). We further examined whether Eiger expression is required for either scrib mutant cells or surrounding wild-type cells by knocking down eiger only in scrib clones. We found that knock-down of eiger within scrib clones was sufficient to significantly increase animal lethality (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that Eiger signaling originates within the scrib clones and acts in an autocrine fashion. The same result was obtained when we knocked down wengen, a Drosophila TNF receptor that mediates Eiger signaling (Kanda et al., 2002) (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that Wengen acts as a receptor for Eiger in this phenomenon. Together, these results indicate that imaginal epithelia eliminate tumorigenic polarity-deficient cells through Eiger, which behaves like a tumor suppressor.

Figure 1. Eiger is required for elimination of tumorigenic scrib clones.

(A–H’) GFP-labeled wild-type (A–B’) or scrib mutant (C–H’) clones were generated in eye-antennal discs of wild-type (A–D’) or eiger (egr) homozygous mutant (E–H’) animals. scrib clones in eiger mutant animals develop into tumors in pupal eye-antennal tissue (F, F’, arrowheads). Expression of Eiger+W within scrib clones prevented both tumor development and pupal lethality (G–H’).

(I–Q’) GFP-labeled wild-type (I–K’) or scrib mutant (L–Q’) clones were generated in wing discs of wild-type (I–N’) or eiger mutant (O–Q’) animals. Shown are larval wing discs or pupal wings (unfolded with water) at 24, 72, and 96 hours after clone induction. scrib clones in eiger mutant animals form tumors in pupal wings (Q, arrows).

(R–Y) GFP-labeled scrib clones were produced in eye-antennal discs and were stained with anti-Eiger antibody. The XY section (R–U) and the XZ section (V–Y) of the confocal images are shown. BskDN was coexpressed to make the clone bigger for XZ analysis. See Supplemental Data for genotypes.

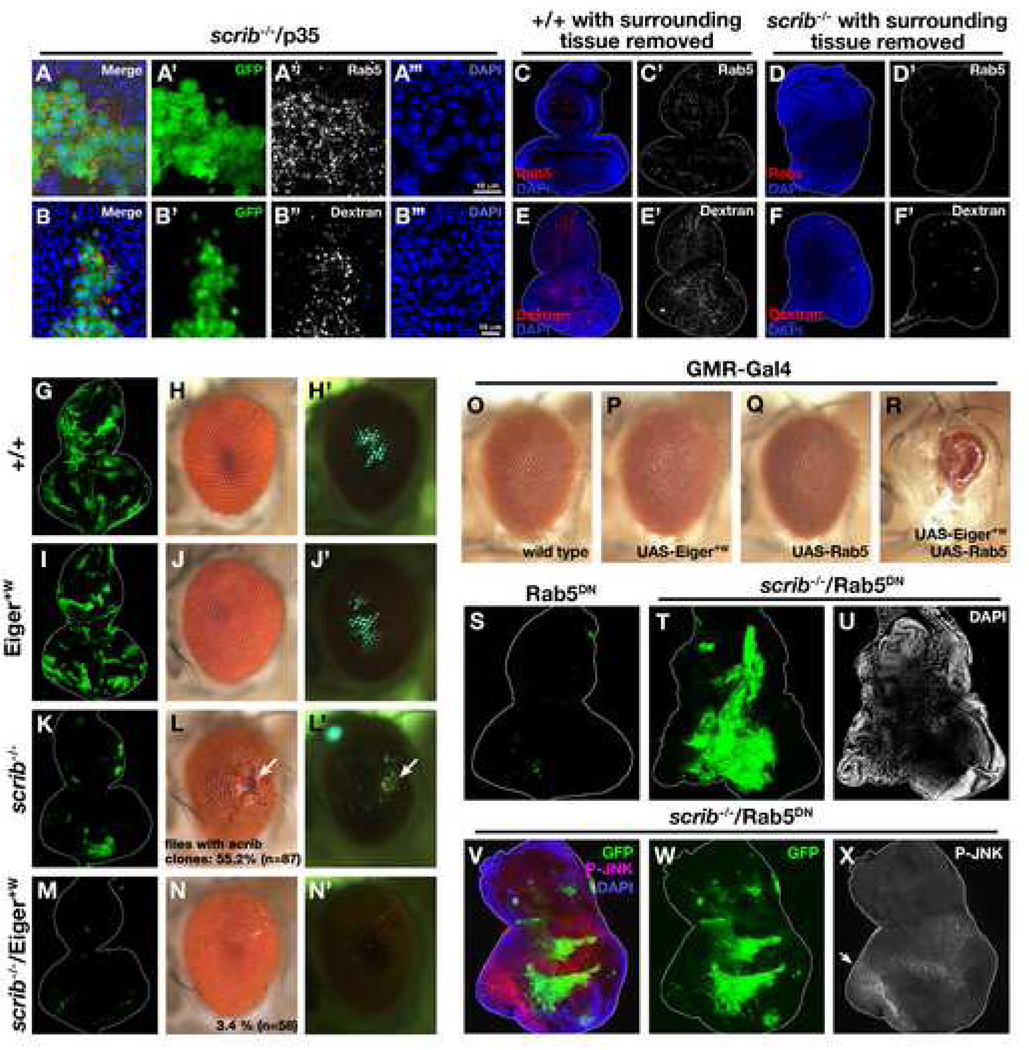

Fig. 4. Eiger-JNK signaling is activated by endocytosis in scrib clones.

(A–A’’’) GFP-labeled scrib clones were generated in eye discs and were stained with anti-DRab5 antibodies.

(B–B’’’) Eye-antennal discs with GFP-labeled scrib mutant clones were assayed for dextran uptake for 60 min (see Experimental Procedures).

(C–F’) Wild-type (C, C’, E, E’) or scrib mutant (D, D’, F, F’) clones were generated in eye-antennal discs and surrounding wild-type tissue was simultaneously removed by a combination of GMR-hid and a recessive cell-lethal mutation CL3R. The discs were either stained with anti-Rab5 antibody (C–D’) or assayed for dextran uptake (E–F’).

(G–N’) GFP-labeled wild-type (G–H’), Eiger+W-expressing (I–J’), scrib mutant (K–L’), or scrib mutant also expressing Eiger+W (M–N’) clones were generated in eye-antennal discs. Percentages of adult flies carrying scrib clones in the eyes are shown (L and N). The sizes of the clones in eye-antennal discs are quantified in Supplemental Fig. S1.

(O–R) Eyes of adult flies expressing Gal4 alone (O), Eiger+W (P), Rab5 (Q), or both Eiger+W and Rab5 (R) are shown.

(S–U) GFP-labeled Rab5DN-expressing (S) or scrib mutant also expressing Rab5DN (T) clones were produced in eye-antennal discs. DAPI staining shows non-cell autonomous overgrowths adjacent to the mutant clones (U, and data not shown), which has also been seen in other endocytic mutants (Moberg et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005). scrib−/−/Rab5DN clones eventually died later during the pupal stage (data not shown). This is probably due to the lethality of endocytosis-deficient cells, which was also reported in other endocytic mutants (Moberg et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005).

(V–X) Eye-antennal discs with GFP-labeled scrib−/−/Rab5DN clones were stained with anti-p-JNK antibodies. Endogenous activation of JNK can be detected in eye discs posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (Agnes et al., 1999; Igaki et al., 2002) (allow), while scrib−/−/Rab5DN clones do not activate JNK. See Supplemental Data for genotypes.

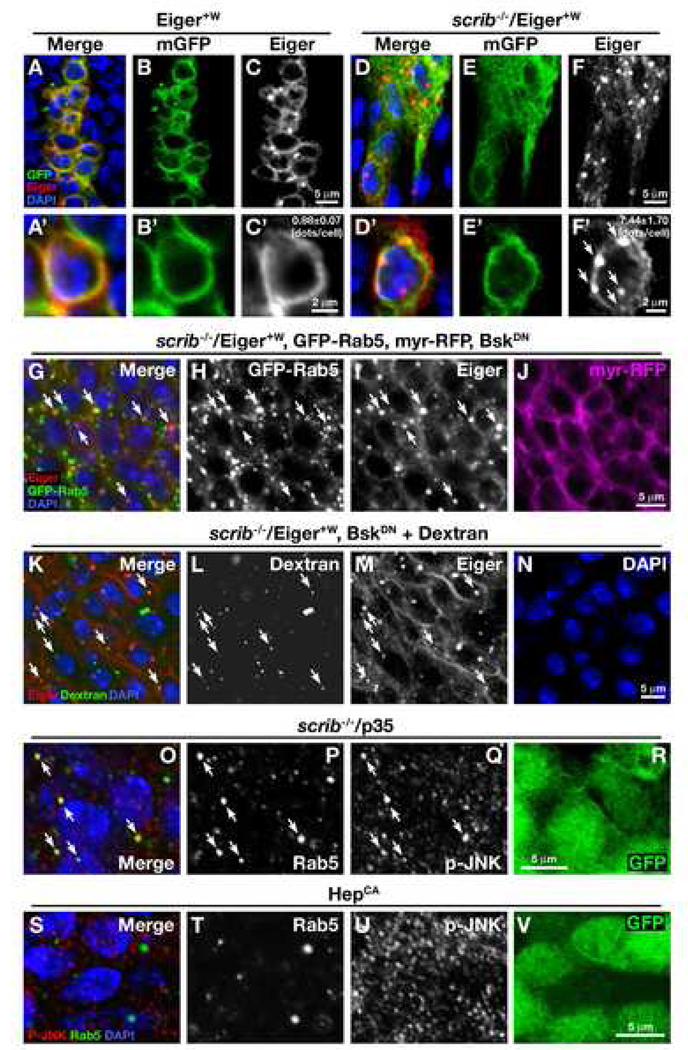

Eiger-JNK signaling is activated in endosomes in scrib mutant clones

To explore the mechanism of how tissue eliminates scrib mutant clones through Eiger signaling, we first asked whether Eiger is up-regulated in these clones. Endogenous Eiger can be detected in the region posterior to the morphogenetic furrow in the eye disc by immunostaining (Supplemental Fig. S3). Unexpectedly, we found that Eiger protein level was down-regulated in scrib mutant clones (Figures 1T and 1X). To explain the discrepancy between the requirement for Eiger and its down-regulation in scrib mutant clones, we hypothesized that Eiger might be mislocalized within subcellular compartments, such as endocytic vesicles, which could enhance both activation of the ligand/receptor signaling and subsequent degradation of the proteins in lysosomes (Miaczynska et al., 2004). To examine the subcellular distribution of Eiger in scrib clones, we made use of the Eiger+W transgene, which could rescue the eiger/scrib mutant phenotype (Figures 1G–1H’), and at the same time allows us to detect Eiger protein in the mutant clones. In the wild-type background, Eiger mostly localized to the plasma membrane, showing an extensive overlap with plasma membrane-targeted CD8-GFP (mGFP) (Figures 2A–2C and 2A’–2C’). In these cells, some staining also appeared as punctate dots reminiscent of vesicle staining (Figure 2C). Intriguingly, in scrib mutant clones, plasma membrane staining was dramatically reduced; however, we observed an increased number of punctate dots staining intensely for Eiger (>8 fold compared to Eiger+W control clones) (Figures 2D–2F and 2D’–2F’). It has been shown that some mammalian ligand/receptor signaling pathways, such as those for the epidermal growth factor (EGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) pathways, are activated in endosomes (Miaczynska et al., 2004). We therefore tested whether the punctate dots in scrib clones were endosomes. Indeed, most of the punctate Eiger foci colocalized with the early endosomal marker GFP-Rab5 (Figures 2G–2I, arrows), while a membrane-targeted control protein myr-RFP did not (Figure 2J). Furthermore, these Eiger dots colocalized with fluorescently-labeled dextran, a marker for fluid-phase endocytosis (Figures 2K–2N, arrows). These results indicate that Eiger is translocated to endosomes in scrib clones. Intriguingly, intense staining of activated JNK (phosphorylated JNK, p-JNK) was detected in the Rab5-positive endosomes in scrib clones (Figures 2O–2R). This endosomal JNK activation was not seen when the pathway was activated by a constitutively active form of the JNK kinase Hemipterous (HepCA) (Figures 2S–2V), suggesting that the endosomal activation of this pathway occurs in Eiger-dependent contexts. Further supporting a ligand-mediated JNK activation, we found that JNK activation in scrib clones was completely abolished in the eiger mutant background (Figure 3). Together, these results indicate that Eiger-JNK signaling is activated in endosomes in scrib mutant clones.

Fig. 2. Eiger-JNK signaling is activated in endosomes in scrib clones.

(A–F, A’–F’) Eiger+W and mGFP were coexpressed in wild-type (A–C, A’–C’) or scrib mutant (D–F, D’–F’) clones in wing discs, and were stained with anti-Eiger antibodies. The numbers of Eiger-positive dots/cell ± S.E. are as follows: Eiger+W clones, 0.88 ± 0.07 (n=105, N=5); scrib/Eiger+W clones: 7.44 ± 1.70 (n=117, N=11) (n=number of cells examined, N=number of discs examined). (G–J) Eiger+W, GFP-Rab5, and myr-RFP were coexpressed in scrib mutant clones in eye disc, and were stained with anti-Eiger antibodies. Arrows indicate specific colocalization of Eiger and GFP-Rab5. A dominant-negative form of JNK (BskDN) was coexpressed to keep the clones alive.

(K–N) Eiger+W was expressed in scrib mutant clones in eye disc, and were assayed for dextran uptake for 120 min (see Materials and Methods). After the dextran uptake, tissues were fixed and stained with anti-Eiger antibodies. Arrows indicate colocalization of Eiger and endocytosed dextran. A dominant-negative form of JNK (BskDN) was coexpressed to keep the clones alive.

(O–R) GFP-labeled scrib clones were generated in eye discs and were co-stained with anti-DRab5 and anti-p-JNK antibodies. Arrows indicate colocalization of these two signals. The caspase inhibitor p35 was co-expressed to keep the clones alive. No signs of compensatory proliferation or non-cell autonomous growth were seen in this mosaic tissue (data not shown).

(S–V) GFP-labeled HepCA-expressing clones were generated in eye discs and were co-stained with anti-DRab5 and anti-p-JNK antibodies. No colocalization was seen in these two signals. See Supplemental Data for genotypes.

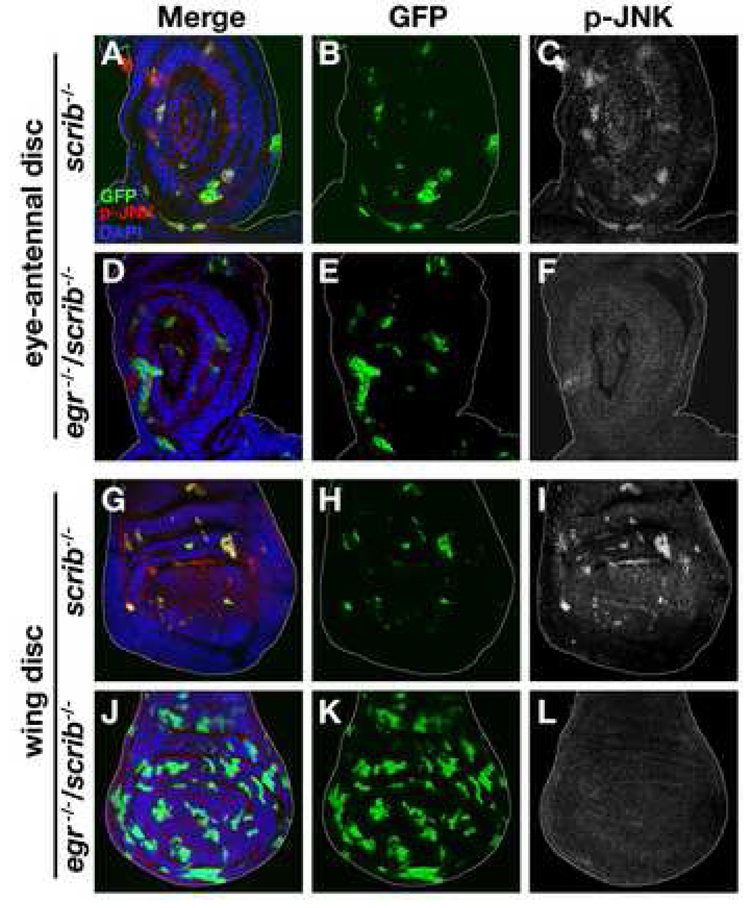

Fig. 3. Eiger is required for JNK activation in scrib clones.

GFP-labeled scrib clones were generated in eye-antennal discs or wing discs of wild-type (A–C, G–I) or eiger (egr) mutant (D–F, J–L) larvae, and were stained with anti-p-JNK antibodies. See Supplemental Data for genotypes.

scrib clones increase endocytosis

A possible mechanism by which Eiger-JNK signaling is activated through the endocytic pathway in scrib clones could be a regulated/increased endocytosis in these clones. We therefore examined the endocytic activities in wild-type and scrib mutant clones in two ways, and found that this was indeed the case. First, we found that the number of Rab5-positive early endosomes was significantly increased in scrib mutant clones compared to surrounding wild-type tissue (Figures 4A–4A’’’). Secondly, uptake of fluorescently-labeled dextran was significantly enhanced in scrib mutant clones compared to wild-type clones (Figures 4B–5B’’’). These results suggest that scrib clones increase endocytosis, which could lead to endocytic activation of Eiger-JNK signaling.

Intriguingly, imaginal discs of scrib mutant animals (tissues entirely made up of scrib mutant cells) overgrow and develop tumors (Bilder, 2004). This suggests that scrib mutant cells are able to grow when they are not surrounded by wild-type cells. Indeed, it has been shown that removal of wild-type tissue from the scrib mosaic disc allows scrib clones to grow (Brumby and Richardson, 2003). Interestingly, when we removed surrounding wild-type tissues from scrib mosaic discs by using the EGUF/hid technique (Stowers and Schwarz, 1999), endocytic activity was no longer enhanced in scrib mutant tissue, but rather was significantly lower than that of wild-type control (Figures 4C–4F’). These data suggest that scrib mutant clones increase endocytosis only when they are surrounded by wild-type tissue.

Endocytosis is essential for Eiger-dependent elimination of scrib clones

Increased endocytosis in scrib clones could be the trigger for the endosomal activation of Eiger-JNK signaling. We tested this hypothesis in three ways. First, if increased endocytosis of Eiger activates its signaling in scrib clones, these clones should be more sensitive to Eiger signaling than wild-type cells. Most scrib clones generated in eye discs are eliminated during development, but a small number of mutant clones can survive into adulthood (Figures 4L and 4L’, arrows). While Eiger+W expression in clones had only a moderate effect on the size of the clones (19.7% reduction compared to wild-type control; compare Figures 4G and 4I; quantified in Supplemental Fig. S1) and no effect on adult eye morphology (compare Figures 4H and 4J) on its own, it strongly enhanced the elimination of scrib clones in developing eye discs (86.5 % reduction compared to scrib control; compare Figures 4K and 4M; quantified in Supplemental Fig. S1) and resulted in adult eyes with no scrib clones (compare Figures 4L, 4L’, 4N, and 4N’). These results indicate that scrib clones are indeed hyper-sensitive to Eiger signaling.

Secondly, we examined whether enhanced endocytosis could stimulate Eiger signaling. Elevation of Eiger expression by Eiger+W in eye discs causes no morphological defect in the adult eye (Figures 4O and 4P). However, when endocytosis is enhanced by co-expression of Rab5 (Bucci et al., 1992; Wucherpfennig et al., 2003), it caused a severe small-eye phenotype (Figure 4R). This small-eye phenotype was indistinguishable from that caused by strongly activated Eiger signaling (Igaki et al., 2002; Moreno et al., 2002). These results suggest that endocytosis is crucial for activation of Eiger signaling.

Finally, we tested the role of endocytosis in the elimination of scrib clones by blocking endocytosis using a dominant-negative form of Rab5 (Rab5DN) (Entchev et al., 2000). Strikingly, scrib clones that were also expressing Rab5DN were not eliminated but grew aggressively (Figure 4T; compare with scrib alone in Figure 4K or Rab5DN expression alone in Figure 4S). Furthermore, these scrib/Rab5DN clones no longer activated JNK signaling (Figures 4V–4X, compare with Figure 3), supporting our hypothesis that Eiger-JNK signaling is activated by endocytosis in scrib clones. We also noticed that p-JNK staining was seen strongly outside of the scrib/Rab5DN clones, suggesting that surrounding wild-type cells are being outcompeted by these clones. Together, these results indicate that scrib clones are eliminated by endocytic activation of JNK signaling through endocytosis of Eiger.

Discussion

Clones of cells mutant for Drosophila tumor suppressor genes such as scrib or dlg are eliminated from imaginal discs, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved fail-safe mechanism that eliminates oncogenic cells from epithelia. Here, we report that this elimination of mutant cells is accomplished by endocytic activation of Eiger/TNF signaling. Eiger is a conserved member of the TNF superfamily in Drosophila, but its physiological function has been elusive. Although ectopic overexpression of Eiger can trigger apoptosis (Igaki et al., 2002; Moreno et al., 2002), flies deficient for eiger develop normally and exhibit no morphological or cell death defect (Igaki et al., 2002). Here, we have shown that Eiger is required for the elimination of oncogenic mutant cells from imaginal epithelia. This not only provides an explanation for previous unexplained observations, but also argues that Eiger behaves like an intrinsic tumor suppressor in a fashion similar to mammalian p53 or ATM, which causes no phenotype when mutated but protects animals as tumor suppressors when their somatic cells are damaged (Lowe et al., 2004).

The intrinsic tumor suppression found in scrib mutant clones was also observed in dlg mutant clones, suggesting that this is a mechanism triggered by loss of epithelial basolateral determinants. Intriguingly, we found that mutant clones of salvador, the hippo pathway tumor suppressor (Tapon et al., 2002), were not susceptible to similar effect of Eiger (data not shown). These data suggest that the Eiger-JNK pathway behaves as an intrinsic tumor suppressor that eliminates cells with disrupted cell polarity.

It is intriguing that Eiger’s tumor suppressor-like function is dependent on endocytosis. Our data show that Eiger is translocated to endosomes through endocytosis and activates JNK signaling in these vesicles. Moreover, blocking endocytosis abolishes both JNK activation and Eiger-dependent cell elimination. Endocytic activation of signal transduction has been observed for EGF and β2-adrenergic receptor signaling in mammalian cells (Miaczynska et al., 2004). After endocytosis, these ligand/receptor complexes localize to endosomes, where they meet adaptor or scaffold proteins that recruit downstream signaling components (McDonald et al., 2000; Miaczynska et al., 2004). Therefore, the endocytic activation of Eiger/TNF-JNK signaling might also be achieved by the recruitment of its downstream signaling complex to the endosomes, possibly through a scaffold protein that resides in endosomes. Recent studies in Drosophila have shown that components of the endocytic pathway, vps25, erupted, and avalanche, function as tumor suppressors (Lu and Bilder, 2005; Moberg et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005). Furthermore, mutations in endocytosis proteins have been reported in human cancers (Floyd and De Camilli, 1998). Thus, de-regulation of endocytosis may contribute to tumorigenesis. Our study provides new mechanistic insights into the role of endocytosis in tumorigenesis.

Mammalian TNF superfamily consists of at least 19 members (Aggarwal, 2003; Locksley et al., 2001). While many have been shown to play important roles in immune responses, hematopoiesis, and morphogenesis, the physiological functions for other members have yet to be determined (Aggarwal, 2003; Locksley et al., 2001). Mechanisms that eliminate damaged or oncogenic cells from epithelial tissues are essential for multicellular organisms, especially for long-lived mammals like humans. The tumor-suppressor role of Eiger might have evolved for host defense or elimination of dying/damaged cells, such as cancerous cells, very early in animal evolution. Given that components of the Eiger signaling machinery (such as Eiger, endocytic pathway components, and JNK pathway components) are conserved from flies to humans, it is also possible that Eiger and its mammalian counterparts are components of an evolutionarily conserved fail-safe by which animals maintain their epithelial integrity to protect against neoplastic development.

Experimental Procedures

Fly Strains and Generation of Clones

Fluorescently-labeled clones were produced in larval imaginal discs using the following strains: y,w, eyFLP1; Act>y+>Gal4, UAS-GFP; FRT82B, Tub-Gal80 (82B ey-GFP tester), y,w, eyFLP1; Act>y+>Gal4, UAS-myrRFP, G454; FRT82B, Tub-Gal80 (82B ey-RFP tester), w, UAS-mGFP, hsFLP1.22; Tub-Gal4, FRT82B, Tub-Gal80 (82B hs-GFP tester), and y,w eyFLP1; Tub-Gal80, FRT40A; Act>y+>Gal4, UAS-GFP (40A tester). Heat-shock clones were induced by larval heat shock at 37°C for 20 min at 48 hr after egg laying. Additional strains used are as follows: egr1 (Igaki et al., 2002), scrib1 (Bilder and Perrimon, 2000), UAS-EigerW (Igaki et al., 2006), UAS-BskDN (Adachi-Yamada et al., 1999b), UAS-HepCA (Adachi-Yamada et al., 1999a), UAS-p35, UAS-GFP-Rab5 (Wucherpfennig et al., 2003), UAS-Rab5 (Entchev et al., 2000), and UAS-Rab5DN (Entchev et al., 2000). UAS-myrRFP was a kind gift of H.C. Chang.

Histology

Larval tissues were stained with standard immunohistochemical procedures using rabbit anti-Eiger polyclonal antibody R1 (1:250-500), mouse anti-phospho-JNK monoclonal antibody G9 (Cell Signaling, 1:100), or rabbit anti-DRab5 antibody (Wucherpfennig et al., 2003) (1:50), and were mounted with Vectashield-DAPI mounting medium (VECTOR). anti-Eiger R1 antisera was raised against the extracellular domain of Eiger (without the TNF homology domain) and was absorbed with egr1 mutant larval tissues. The specificity of the anti-Eiger R1 antibody was confirmed by immunostaining of imaginal discs from wild-type and eiger homozygous mutant larvae (Supplemental Figure S3). For dextran uptake, larvae were dissected in Schneider’s media and were incubated at 25°C in the same media containing 1mg/ml dextran-Alexa546 for 120 min.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. De Camilli, F. Nakatsu and the Xu lab members for discussions, A. Igaki, R. Li, S. Ohsawa, and T. Sawada for technical support, R. Pagliarini and D. Nguyen for comments on the manuscript, K Sugimura for helping quantitative analysis, M. Gonzalez-Gaitan for anti-DRab5 antibodies, and T. Adachi-Yamada, D. Bilder, H.C. Chang, M. Gonzalez-Gaitan, B. Hay, M. Nakamura, N. Perrimon, and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks. This work was supported by a grant from NIH/NCI to TX. TI was supported in part by a fellowship of Yamanouchi Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders, and was a recipient of the long-term fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program. JCPP was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the Spanish Ministry of Education. TX is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adachi-Yamada T, Fujimura-Kamada K, Nishida Y, Matsumoto K. Distortion of proximodistal information causes JNK-dependent apoptosis in Drosophila wing. Nature. 1999a;400:166–169. doi: 10.1038/22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi-Yamada T, Gotoh T, Sugimura I, Tateno M, Nishida Y, Onuki T, Date H. De novo synthesis of sphingolipids is required for cell survival by down-regulating c-Jun N-terminal kinase in Drosophila imaginal discs. Mol Cell Biol. 1999b;19:7276–7286. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:745–756. doi: 10.1038/nri1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnes F, Suzanne M, Noselli S. The Drosophila JNK pathway controls the morphogenesis of imaginal discs during metamorphosis. Development. 1999;126:5453–5462. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N, Kango M, Mishra A, Sinha P. Neoplastic transformation and aberrant cell-cell interactions in genetic mosaics of lethal(2)giant larvae (lgl), a tumor suppressor gene of Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1995;172:218–229. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Y, Hayashi S, Levine A, Wieschaus E. Regulation of armadillo by a Drosophila APC inhibits neuronal apoptosis during retinal development. Cell. 1998;93:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D. Epithelial polarity and proliferation control: links from the Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressors. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1909–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.1211604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Perrimon N. Localization of apical epithelial determinants by the basolateral PDZ protein Scribble. Nature. 2000;403:676–680. doi: 10.1038/35001108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell MJ, Radisky D. Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumby AM, Richardson HE. scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. Embo J. 2003;22:5769–5779. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci C, Parton RG, Mather IH, Stunnenberg H, Simons K, Hoflack B, Zerial M. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell. 1992;70:715–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entchev EV, Schwabedissen A, Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Gradient formation of the TGF-beta homolog Dpp. Cell. 2000;103:981–991. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish EM, Molitoris BA. Alterations in epithelial polarity and the pathogenesis of disease states. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1580–1588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406023302207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd S, De Camilli P. Endocytosis proteins and cancer: a potential link? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:299–301. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada F, Bienz M. A Drosophila APC tumour suppressor homologue functions in cellular adhesion. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:208–213. doi: 10.1038/ncb755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan IK, Bilder D. Regulation of imaginal disc growth by tumor-suppressor genes in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:335–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.100738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki T, Kanda H, Yamamoto-Goto Y, Kanuka H, Kuranaga E, Aigaki T, Miura M. Eiger, a TNF superfamily ligand that triggers the Drosophila JNK pathway. Embo J. 2002;21:3009–3018. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki T, Pagliarini RA, Xu T. Loss of cell polarity drives tumor growth and invasion through JNK activation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda H, Igaki T, Kanuka H, Yagi T, Miura M. Wengen, a member of the Drosophila tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, is required for Eiger signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28372–28375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SW, Cepero E, Evan G. Intrinsic tumour suppression. Nature. 2004;432:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature03098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Bilder D. Endocytic control of epithelial polarity and proliferation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1232–1239. doi: 10.1038/ncb1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PH, Chow CW, Miller WE, Laporte SA, Field ME, Lin FT, Davis RJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin 2: a receptor-regulated MAPK scaffold for the activation of JNK3. Science. 2000;290:1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaczynska M, Pelkmans L, Zerial M. Not just a sink: endosomes in control of signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg KH, Schelble S, Burdick SK, Hariharan IK. Mutations in erupted, the Drosophila ortholog of mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101, elicit non-cell-autonomous overgrowth. Dev Cell. 2005;9:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno E, Yan M, Basler K. Evolution of TNF signaling mechanisms: JNK-dependent apoptosis triggered by Eiger, the Drosophila homolog of the TNF superfamily. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1263–1268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarini RA, Xu T. A genetic screen in Drosophila for metastatic behavior. Science. 2003;302:1227–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.1088474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers RS, Schwarz TL. A genetic method for generating Drosophila eyes composed exclusively of mitotic clones of a single genotype. Genetics. 1999;152:1631–1639. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Harvey KF, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Schiripo TA, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. salvador Promotes both cell cycle exit and apoptosis in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Cell. 2002;110:467–478. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U, Tanentzapf G, Ward R, Fehon R. Epithelial cell polarity and cell junctions in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:747–784. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BJ, Mathieu J, Sung HH, Loeser E, Rorth P, Cohen SM. Tumor suppressor properties of the ESCRT-II complex component Vps25 in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2005;9:711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlirova M, Jasper H, Bohmann D. Non-cell-autonomous induction of tissue overgrowth by JNK/Ras cooperation in a Drosophila tumor model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13123–13128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Bilder D. The Drosophila tumor suppressor vps25 prevents nonautonomous overproliferation by regulating notch trafficking. Dev Cell. 2005;9:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DF, Bryant PJ. The discs-large tumor suppressor gene of Drosophila encodes a guanylate kinase homolog localized at septate junctions. Cell. 1991;66:451–464. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wucherpfennig T, Wilsch-Brauninger M, Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Role of Drosophila Rab5 during endosomal trafficking at the synapse and evoked neurotransmitter release. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:609–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.