1. Introduction

1.1 Importance of the Phosphoester Handle in Biological Systems

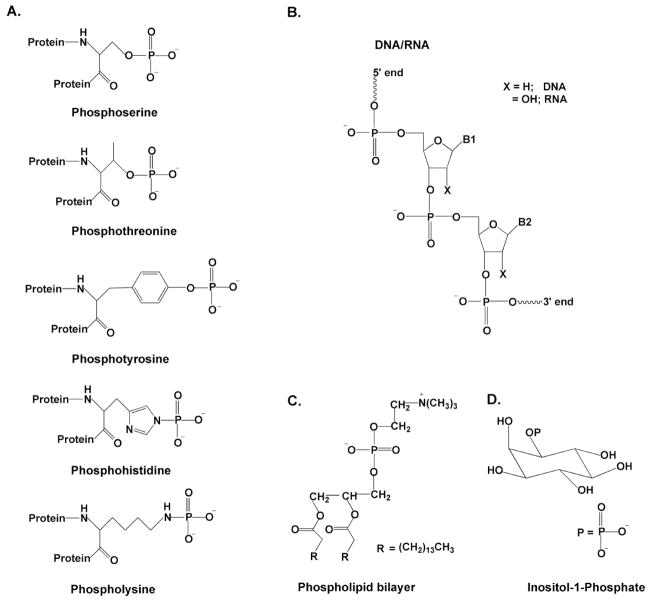

Proteins, nucleic acids, lipids and various other smaller biomolecules are united by the presence of a common chemical entity of paramount and unique importance—the phosphate ester. In proteins, phosphomonoester groups are added as reversible post-translational modifications to serine, threonine, or tyrosine amino acid side chains, and serve as a switch for intracellular signaling cascades (phosphoserine, phosphothreonine or phosphotyrosine)1. Alternatively, phosphoamide linkages involving the nitrogens of histidine or lysine side chains serve as high energy phosphoryl donors in multistep phosphoryl transfer reactions (Fig. 1A)2. In nucleic acids, the phosphodiester linkage provides the exceptionally stable polymeric backbone upon which the coding information of the nucleic acid bases are carried (Fig. 1B). In this regard, the biological selection of phosphate ester linkages for long term information storage in DNA may in part reside in their resistance to hydrolysis (t1/2 = 30 million years)3, and the requirement for a charged linkage that promotes aqueous solubility and deters aggregation. In phospholipids, the negatively charged phosphate monoester head group imbues phospholipid bilayers with their aqueous affinity that is crucial for forming functional cell membranes (Fig. 1C). Finally, phosphorylated polyalcohols such as inositol play a key role in intracellular signaling cascades that allow regulation of a diverse array of cellular processes (Fig. 1D)4. Because the phosphate ester group is used in numerous ways in biology, a detailed molecular understanding of the interactions of proteins, enzymes and small molecules with these ubiquitous functional groups is of great interest.

Figure 1.

Various biological forms of phosphate esters. (A) Phosphorylated amino acids (B) Nucleic acids (C) Phospholipids (D) inositol-1-phosphate.

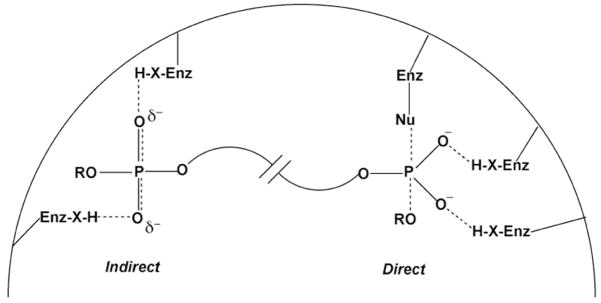

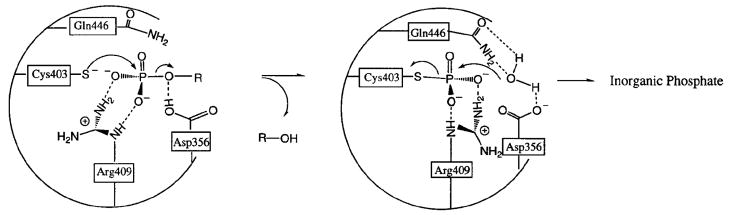

The primary focus of this review is enzymes that interact with phosphate esters to promote catalysis. These interactions may be divided into two general classes: indirect and direct. The indirect interaction involves noncovalent bonding of the enzyme to an oxygen atom of a phosphate ester group that does not undergo a change in covalent bonding during the enzymatic reaction (Fig. 2). By definition, indirect interactions must involve substrates (such as DNA and RNA) that contain more than one phosphate ester group, and the specific binding energy of the enzyme with such groups can be used to drive catalysis in a variety of ways as discussed in detail below. In contrast, the direct interaction (at least within the scope of this review) involves noncovalent bonding to a phosphate ester center that is the direct target of a nucleophilic substitution reaction (Fig. 2). In terms of catalysis, both indirect and direct interactions can have comparable large effects in lowering the activation barrier for a given reaction. As will be illuminated throughout this review, the dense display of lone pair electrons on the phosphate ester oxygens, and the overall negative charge of the phosphate ester group provide unique opportunities for powerful hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions that may be used to either destabilize ground states or stabilize transition states, as required for enzymatic catalysis (Fig. 2)5.

Figure 2.

Examples of indirect and direct catalytic interactions of an enzyme with phosphate ester groups. The direct interaction (right) involves a phosphate group that undergoes nucleophilic substitution during the course of the enzymatic reaction. Hydrogen bonding groups (H-X) are used to stabilize the charge development in a pentacoordinate transition state. Indirect noncovalent interactions with a phosphate ester (left) can be used to position a substrate, electrostatically destabilize a ground state, or to a stabilize a transition state. Many examples of catalytically important indirect interactions are found in Sections 6 and 7.

1.2 Chemical Substitutions at Phosphate Ester Oxygens

One general goal in the field of chemical biology and enzymology is to develop chemical tools that can provide unique insights into the nature of protein-ligand interactions that go beyond those provided by structural methods such as X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy. The idealized objective is to construct chemical congeners of naturally occurring biological functional groups that discretely probe one energetic aspect of an interaction. Thus, the change in a binding interaction of the congener in the ground state and transition state relative to the actual functional group provides a measure of the energetic importance and the nature of the native interaction. Of course, truly selective perturbations of a single interaction are seldom if ever realized, and one is always faced with the harsh reality that observed energetic perturbations to such complex systems as enzyme-substrate complexes will always be a mixture of short-range and long-range effects brought about by the cooperative nature of the binding interactions. Nevertheless, chemical perturbation approaches can be qualitatively and quantitatively useful if binding measurements are made for each stable complex along a reaction coordinate and the structures of the complexes are also available. Moreover, as is the major focal point of this review, combining chemical perturbations approaches with protein mutagenesis can provide more compelling insights than either approach alone.

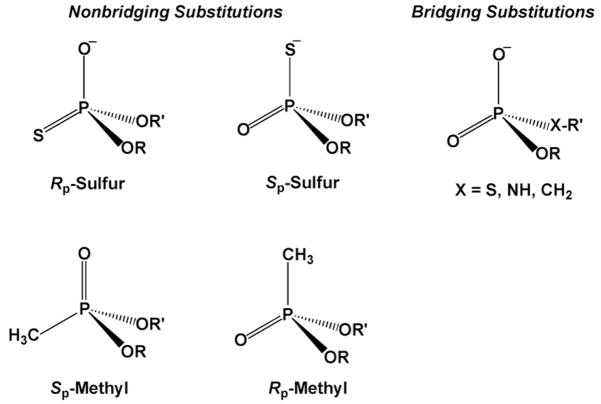

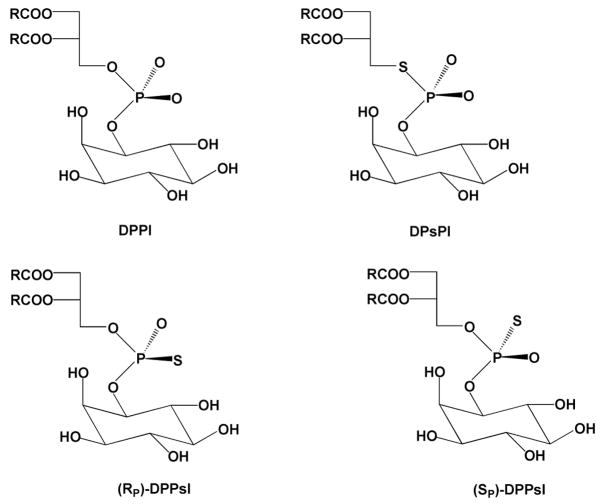

Frequently used congeners for phosphate diesters are shown in Figure 3 (analogous congeners can be made for monoesters and triesters of phosphate). The depicted chemical substitutions may be divided into two classes depending on whether a nonbridging or bridging oxygen is replaced. Stereospecific substitution of a nonbridging oxygen with sulfur or a methyl group is often performed to explore the importance of hydrogen bonding, steric fit, or electrostatic interactions with a specific oxygen. Contrastingly, substitution of a low pKa sulfur for a bridging oxygen is assumed to destabilize the ester linkage to nucleophilic attack by relinquishing the requirement for acid catalysis of expulsion of the high pKa oxygen leaving group. The chemical rationale for these effects of nonbridging and bridging substitutions is discussed in detail in section 2. We also note here that substitution of single nonbridging oxygen of a prochiral phosphate diester with another atom or functional group generates a stereocenter as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Common nonbridging and bridging chemical substitutions of oxygen atoms of phosphate esters. In this figure, the stereochemical priority is R > R′.

1.3 Scope

The literature where oxygen atoms of phosphate esters have been substituted to investigate properties of various biological systems is extensive and dates back at least 45 years6. This review focuses on studies that have used sulfur and carbon substitution of phosphate ester oxygens to probe the energetics of protein-ligand interactions, with a deliberate emphasis on enzymatic reactions. Notably, we specifically exclude studies in which the phosphate ester oxygen is coordinated to a metal ion in favor of systems where the enzyme itself makes direct contact with the phosphate ester. In this regard, studies using nucleotides fall outside this scope 7–9, and we refer the reader to elegant studies that cover the powerful approach of “metal rescue” in which the damaging effect of sulfur substitution for oxygen is ameliorated by switching to a soft metal that prefers bonding to sulfur10,11,12. In addition, the general approach of using stereospecific sulfur substitution to determine the stereochemical course of enzymatic nucleophilic substitution reactions is not covered to any significant extent and we refer the reader elsewhere for this methodology8,6,13. Our approach is to first provide an overview of the chemical basis for the energetic effects of sulfur and methyl substitution for oxygen, then present the free energy analysis that describes the combined energetic effects of phosphate ester substitution and mutagenesis, and finally, provide representative examples that exemplify the utility of the approach.

2. Noncovalent Interactions with Phosphate Esters

A compelling interpretation of an observed energetic effect arising from substitution of an oxygen atom of a phosphate ester with sulfur or a methyl group requires careful consideration of the nature of the chemical perturbation, and if possible, the structure of the protein-bound ligand. Although the following section critically presents the possible outcomes of such substitutions, in practice, the observed energetic effects often are quite unambiguous with respect to identifying important enzyme-oxygen contacts. Very often, careful studies that combine both chemical substitution and protein mutagenesis can provide interaction maps at various steps along a reaction coordinate that can be as detailed as structural studies. Most importantly, direct experimental evidence for transition state interactions can be revealed, whereas these contacts can only be indirectly inferred from structural studies.

2.1 Hydrogen Bonding

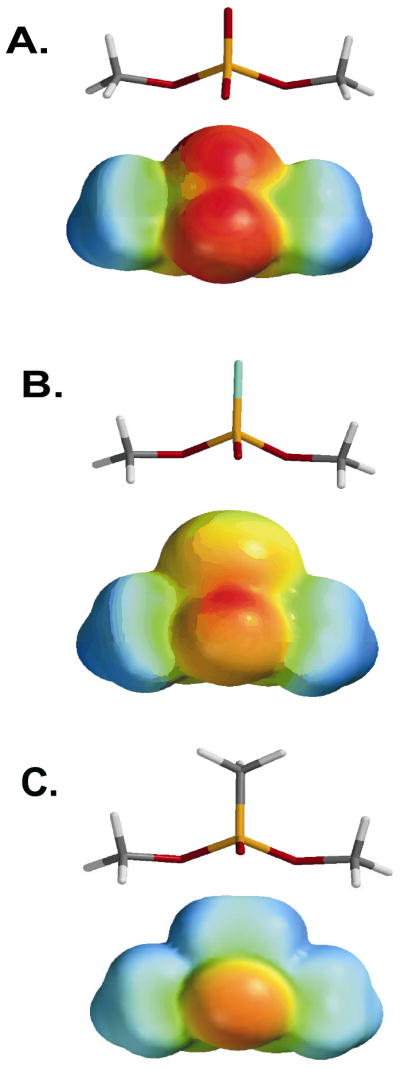

Substitution of sulfur or a methyl group for a nonbridging oxygen of a phosphate ester is expected to have a significant effect on hydrogen bond enthalpy, but the net free energy effect of the substitution is difficult to predict because even these fairly conservative replacements result in complex changes to the system. For instance, sulfur substitution preserves the overall charge of the group but it has lower electronegativity than oxygen, which would be expected to lead to weaker hydrogen bonding because the strength of hydrogen bonds is largely dependent on the magnitude of the charge on the donor and acceptor groups5,14. These differences between phosphate esters and phosphothioesters may be easily visualized as electrostatic potentials plotted on the van der Waals surfaces of these groups (Fig. 4). However, this simple expectation based on electronegativity differences is complicated by the fact that the negative charge of a phosphomonoester and diester linkage is evenly delocalized between all nonbridging oxygen atoms, whereas P-S bonds have less double bond character in aqueous solution as judged by NMR chemical shift and pKa data15, and therefore, possess a greater net negative charge than a given nonbridging phosphate ester oxygen15. However, it should be pointed out that crystallographic data16 and quantum mechanical calculations 17 have indicated that the P-O and P-S bond orders are both close to 1.5, with somewhat greater negative charge on oxygen than sulfur. The previous computational result is recapitulated in the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* electrostatic potentials for the phosphorothioate dimethyl ester shown in Figure 4B. The reasons for these discrepancies between solution, crystallographic and computational methods remain unclear. Further compounding quantitative predictions of the energetic outcome of sulfur substitution is the fact that hydrogen bonds are strongest when the pKa values of the donor and acceptor are matched 5,18,19. Thus, without detailed knowledge of the proton affinities of the donor and acceptor groups in the protein microenvironment, it is exceedingly difficult to predict net energetic effects of sulfur substitution. Despite potential complications in the meaningful interpretation of sulfur substitution effects, we will see from numerous real examples that very useful insights into hydrogen bonding interactions can typically be gleaned from such studies. When unexpected energetic outcomes arise from sulfur substitution, these too can elucidate subtle properties of the system, especially if structural information is also available.

Figure 4.

Lowest energy structures and electrostatic potential energy surfaces for esters of dimethylphosphate substituted with sulfur or CH3 at a nonbridging oxygen. (A) dimethyl ester of phosphate, (B) dimethyl ester of thiophosphate, (C) dimethyl ester of methylphosphonate. Geometries and electrostatic potentials were calculated using Spartan04 using DFT/B3LYP/6-31G*.

Substitution of a methyl group for a nonbridging oxygen of a phosphate diester presents a somewhat simpler situation in terms of possible energetic outcomes with respect to hydrogen bond donors. The most obvious effects arising from this substitution are the complete ablation of negative charge and the substitution of a functional group (CH3) that has no lone pair electrons for accepting hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4C)17. Accordingly, stereospecific substitution of a methyl group for oxygen would be expected to give rise to a larger damaging effect than the analogous sulfur substitution. Despite the apparent straight forward nature of stereospecific methyl substitution, it must be realized that oxygen replacement removes the negative charge that is delocalized over both nonbridging oxygens, and therefore, the effect is not strictly stereospecific. In addition, methyl substitution on a nonbridging atom also makes the charge on the bridging oxygen atom more electropositive than in a phosphate ester. This effect arises because of the increased electrophilicity of the phosphorus atom that in turn increases bond order to the bridging oxygen atoms. These outcomes have ramifications for interpretation as presented in the discussion below pertaining to electrostatics.

The final and most mechanistically informative phosphate diester substitution is the replacement of a bridging oxygen leaving group with sulfur. The power of this chemical perturbation resides in the dramatically lower pKa value of a thiolate leaving group (pKa ~ 8) as compared to oxygen (pKa ~ 15)20, the smaller bond dissociation energy of the P-S bond relative to the P-O bond (~50 and 100 kcal/mol, respectively)21, both of which increase the leaving group potential of bridging thiophosphate esters. For nucleophilic substitution reactions that have largely dissociative character, lowering the pKa of the leaving group can have a profound effect on the reaction rate22. As described below, the excellent leaving group ability of sulfur provides the basis for the powerful “sulfur rescue” methodology, one of the most unambiguous approaches for identifying an enzyme amino acid side chain that serves as a proton donor (general acid) to the poorer oxygen leaving group (see section 7.2.2).

2.2 Electrostatic Effects

One of the most important aspects of phosphate monester and diester linkages is their negative charge, which can be a powerful recognition feature especially in a low dielectric environment like that often found in enzyme active sites. Thus, it is useful to consider the possible electrostatic consequences of sulfur or methyl substitution for a nonbridging oxygen. For simplicity, we consider a phosphate diester linkage with a formal charge of −1, but similar considerations would hold for a monoester with a charge of −2 at neutral pH. Since hydrogen bonds can involve charged groups, and are themselves electrostatic in nature18, we explicitly define an electrostatic interaction as involving a charged group greater than about 3.5 angstroms from the negatively charged oxygen. According to Coulomb’s law (eq 1) the

| (1) |

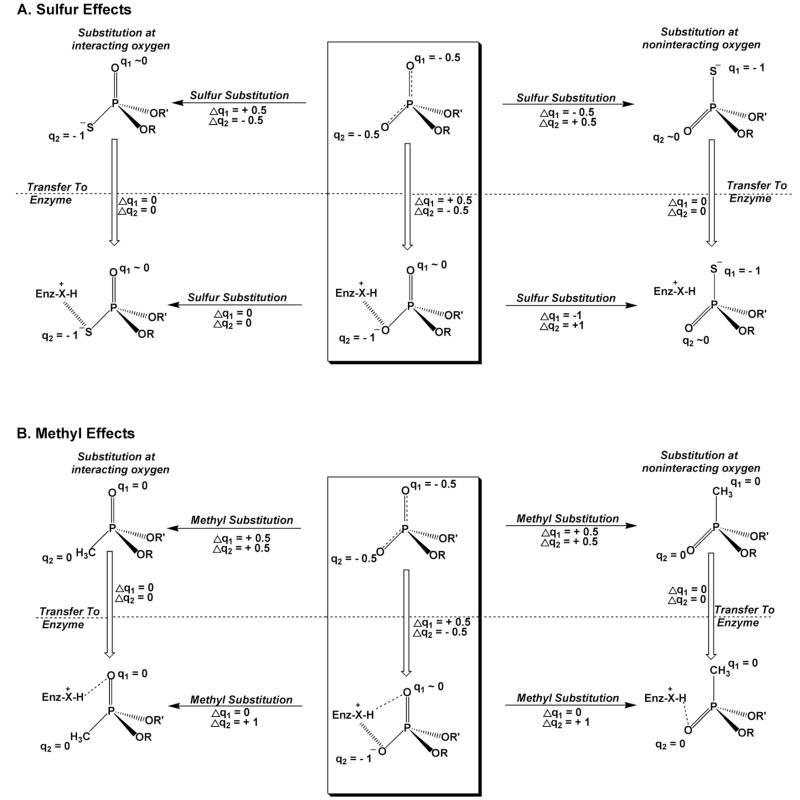

energy (E) of such an interaction will show an inverse dependence on the effective dielectric constant (ε) and the distance (r) between the two groups with effective charges q1 and q2. This simple equation provides a useful basis for understanding electrostatic effects upon sulfur or methyl substitution, and reveals some limitations for interpreting observed effects. Accordingly, we make the following general conclusions:

The magnitude of the electrostatic effect will depend on the change in effective charge on each nonbridging atom or group in the phosphate ester upon substitution with sulfur or a methyl group. It may be reasonably assumed that in a solution the single negative charge on a phosphate diester is evenly delocalized over both nonbridging oxygens and that (1) this charge becomes more localized on sulfur upon substitution15, and (2) that the charge is totally ablated upon methyl substitution. However, for protein environments different scenarios can be envisioned. For instance, when one oxygen is interacting with a protein cationic group, the negative charge distribution will shift towards that oxygen. Thus, upon stereospecific substitution of sulfur for the interacting oxygen, there will be a smaller change in charge at that position than in aqueous solution, and in the absence of any other effects, the substitution may have little consequence on the binding interaction (Fig. 5A). Similarly, substitution of the other noninteracting oxygen with sulfur may shift the charge density away from the oxygen that is involved in the electrostatic interaction, and weaken binding (Fig. 5A). In the case of the methyl group, substitution of either nonbridging oxygen will ablate the charge, leading to the prediction that long range electrostatic interactions may show no stereoselectivity, while direct hydrogen bonding interactions may show a strong stereoselective effect of methyl substitution (Fig. 5B).

The magnitude of the electrostatic effect upon substitution will depend on the change in distance between the effective charge on the nonbridging atom and a charged protein group. The length of the P-O bond (1.51 A) is considerably shorter than the P-S bond (1.97 A), but nearly identical to the P-C bond (1.49 A) (see models in Fig. 4)17. Therefore, in terms of distance effects only and assuming that no steric conflicts are present, sulfur substitution may make a charged interaction stronger.

The magnitude of the electrostatic effect will depend on whether the dielectric constant of the protein binding pocket remains unchanged upon substitution. A common simplifying assumption in this methodology is that the dielectric environment of the protein does not change when the oxygen, sulfur or methyl substituent are bound. Of course, this is not directly testable, and if waters of hydration are changed between the free and bound ligand or protein, or if structural rearrangements arise from substitution, then unexpected outcomes could result that complicate the interpretation.

Figure 5.

Possible changes in charge of the nonbridging phosphate diester atoms upon substitution with sulfur or a methyl group in solution and in an enzyme active site. The charges shown on the atoms are approximate and are merely used for illustrating the possible effects. Two cases are depicted: one where the substituent interacts with an enzyme group (left), and one where the substituent does not interact (right). The effects on hydrogen bonding and electrostatics in an enzyme active site are depicted. (A) The center box shows the charge distribution of a phosphate diester in solution, and upon transfer to an enzyme active site (vertical arrow). An enzyme cationic group (X-H+) is depicted that can serve as a charged hydrogen bond donor (hashed lines). Thus, the change in charge (Δq2) for the interacting oxygen upon transfer is −0.5 whereas the other noninteracting oxygen shows a +0.5 change (Δq1). Sulfur substitution for oxygen leads to accumulation of a full negative charge on S for both sulfur diastereomers (horizontal arrows, top). Unlike oxygen, a thio substituted position that interacts with a cationic enzyme group will feel little change in charge (Δq2 or Δq1), because sulfur is already carrying a full negative charge in solution (left vertical arrow). A similar analysis is shown for a noninteracting position (top, right vertical arrow). The net result is that nonbridging thio substitution in the context of the enzyme active site (horizontal arrows, bottom panel A) produces no changes in charge for the directly acting case (right), and large changes in charge for the noninteracting substitution. (B) An analogous scenario for methyl substitution.

2.3 Sterics and Flexibility

The final aspect of methyl and sulfur substitution that should be considered are the differences in sterics and flexibility of the various esters. The van der Waals radius of a sulfur atom is considerably larger (1.85 Ǻ) than oxygen (1.44 Ǻ) whereas a methyl group is closer to isosteric (1.74 Ǻ)6,23. Thus, sulfur substitution could give rise to stereospecific steric conflicts in an enzyme active site, whereas methyl substitution may not. In addition, increased double bond character would be expected for the other nonbridging oxygen upon sulfur and methyl substitution, leading to a shortening of this bond by about 0.06 Ǻ6,15. Computational studies also indicate that there are differences in conformational flexibility of phosphate, phosphorothioate and phosphonate esters that arise from aqueous solvation effects, hydrophobic interactions, as well as electrostatic and steric effects 17. In particular, substitution of the 3′ or 5′ oxygens with sulfur in the phosphodiester linkage of DNA increases local flexibility as determined by computational approaches. In the context of duplex DNA, both methylphosphonate and phosphorothioate substitution can give rise to changes in the minor groove width (widening or narrowing)24, hydration and cation localization in the minor groove25,26, as well as diastereomer specific changes in duplex stability27,28. Finally, it is well documented that methylphosphonate substitution in duplex DNA can result in dynamic bending of the duplex that presumably reflects the diminished charge repulsion of the backbone24,29,30.

3. Chemical Reactivity of Phosphoester, Phosphothioester and Phosphonoester Linkages

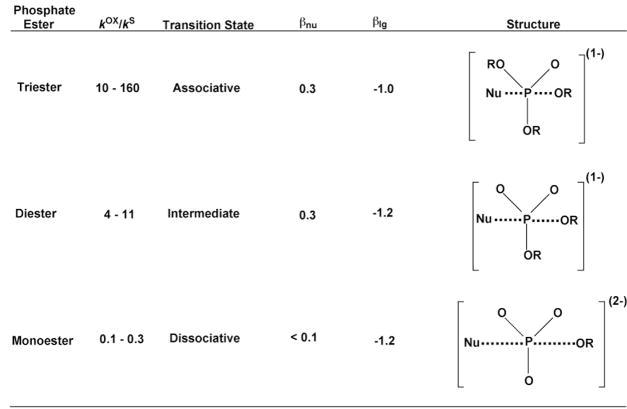

The transition state structures for nucleophilic substitution at phosphorus centers of various phosphate esters have been extensively studied. We make no attempt to comprehensively review this important area, but instead, refer the reader to other literature that cover this aspect of phosphate31–38, phosphorothioate39,40–42, and phosphonate chemistry43. For our purposes, several general trends in the reactivity of these various esters are important to consider when making elemental substitution studies. First, reactions of phosphate esters show a systematic change in transition state structure with monoesters being highly dissociative, triesters highly associative, and diesters of intermediate associative character (Figure 6)31–33,40. Sulfur substitution for a nonbridging oxygen atom of these esters does not significantly change the transition state structure for each of these reactions in solution44, but substantial changes in rate can occur. These “thio effects” on rate (defined as kox/ks) are tabulated in Figure 6 40. Notably, the nonbridging thio effect for a triester is about 25 and 1000-fold greater than a diester and monoester, respectively. These large differences have been reasonably attributed to the different transition state structures for each ester and the electronegativity differences between oxygen and sulfur: the dissociative reaction of the monoester with an electron deficient phosphorus is accelerated by the greater electron donation from sulfur as compared to oxygen, whereas the associative reaction of the triester with an electron rich phosphorus is accelerated by the greater electron withdrawal by oxygen as compared to sulfur. Thus, enzymatic thio effects that differ significantly from these values suggest that other energetic contributions must be present (see above). Key issues with methylphosphonate diesters is that they are potentially more reactive than phosphate diesters and proceed by more associative triester-like mechanisms43,45. For instance, nucleophilic substitution by hydroxide ion is more than 108-fold faster for a methylphosphonate diester than the corresponding phosphate ester43,46.

Figure 6.

Nonbridging thioeffects, transition state structures, and nucleophile and leaving group dependencies for nucleophile substitution with various phosphate esters. See refs 31–42.

4. Free Energy Analysis: Combining Mutagenesis and Chemical Modification

The free energy changes in an enzyme-substrate binding interaction resulting from removal of an enzyme side chain, or upon substitution of a nonbridging oxygen atom with sulfur or a methyl group, may be analyzed using the same conceptual framework established for the effects of site-directed mutagenesis47,48. Since the binding interaction may be present in the ground state Michaelis complex, the enzymatic transition-state, or indeed any state of the enzyme bound substrate, it is possible to obtain interaction maps across an entire reaction pathway. With this formalism, the mutational difference free energies (ΔΔGmut) are typically calculated from the ratio of a binding or kinetic parameter of the wild-type (wt) enzyme and the corresponding value for the mutated enzyme (mut). This is shown in eq 2 and 3 for an equilibrium binding measurement (KD), and a generic kinetic measurement (k), where k could be kcat, kcat/Km or even a single turnover kinetic constant for an enzyme. The difference free energies corresponding to a binding and kcat measurement are depicted in the free energy reaction coordinate diagrams shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Free energy changes associated with binding (−RT ln KD) and catalytic turnover (−RT ln kcat/ν) for a wild-type enzyme (wt) and a mutant form (mut). The difference free energy for binding of the mutant relative to the wild-type in the ground state (ΔΔGmut) and the transition state are shown (ΔΔG‡). An identical diagram can be drawn for chemical substitution of an oxygen for sulfur or a methyl group. See text.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Similarly, in the case of chemical substitution, the difference free energies arising from the substitution (ΔΔGsub) are calculated from the ratio of a binding or kinetic parameter for the oxygen containing substrate (ox) and the corresponding value for the substituted substrate (sub).

| (4) |

| (5) |

We next consider combining mutagenesis with chemical substitution, and the simplest possible expectations for how the substitution effect (ΔΔGsub) changes upon removal of an enzyme side chain that interacts with the substituted position. Substitution effects arise from a variety of factors that stem from the different size and electronic properties of the substituent as compared to oxygen. Typically, nonbridging substitution with sulfur or CH3 gives rise to weaker binding interactions with an enzymatic group in the transition state (we will see numerous examples where this is not true in the ground state, however). In the simplest scenario, if an enzymatic group interacts directly with a nonbridging oxygen, then the substituent effect should be smaller for a mutant enzyme that lacks this group because the interaction was already lost by deletion of the side chain by mutagenesis (i. e. ΔΔGsub → zero for the mutant). In contrast, if there is no change in the substitution effect for a mutant enzyme (i. e. ΔΔGsub is the same for the mutant and wild-type forms), then this provides evidence that the wild-type side chain does not interact with the given nonbridging oxygen (see below). Although mutation of a residue that interacts directly with the nonbridging atom would be expected to produce the largest change in the thio effect, significant changes may also occur if the mutated group alters the structure of the complex, thereby indirectly changing the interaction of the nonbridging oxygen with the enzyme. Thus, the interpretation of an altered thio effect upon mutagenesis is best done in conjunction with structural information.

In principle, the combined damaging effect of sulfur substitution and deleting an amino acid side chain (ΔΔGsub+mut) can be the simple sum of the two individual effects (ΔΔGmut + ΔΔGsub) or may differ from simple additivity by an amount termed the coupling energy (ΔGc, eq 6). In general, a

| (6) |

coupling energy will be observed when either of the single alterations changes the interaction energy between the mutated residue and the substitution site. We note, but do not derive, that the coupling energy may be calculated in a straightforward way from the ratio of the substitution effect (kox/ksub) for the wild type and mutated enzyme forms (eq 7). Obviously, a direct

| (7) |

interaction between an enzyme group and the substituted position would always be expected to give rise to a negative coupling energy term (ΔGc < 0). This follows because removal of the directly interacting enzyme side chain should reduce the substitution effect (i. e. ΔΔGsub → zero because the mutant enzyme can’t “feel” the identity of the substituent anymore), thus making ΔΔGsub+mut smaller than the sum ΔΔGmut + ΔΔGsub. For a noninteracting side chain, its removal should have no effect on the interaction of the nonbridging substituent. Thus the substituent effect would be unchanged as compared to the wild-type enzyme, and the coupling energy would be zero (i.e., ΔΔGsub+mut = ΔΔGmut + ΔΔGsub). Finally, if a distant residue is mutated that indirectly upsets the direct interaction of the enzyme with the substituent group, making it either stronger or weaker, a positive or negative coupling energy will also result. Although this outcome has the potential of providing misleading information as to whether a side chain makes direct or indirect contact with a substituent, additional experiments and/or structural information can turn this ambiguity into a mechanistically informative result reflecting the cooperative nature of the interactions. These various informative outcomes are discussed in the context of the individual enzyme systems explored below.

5. Experimental Techniques

5.1 Modified Substrates and Ligands

It is beyond the scope of this review to comprehensively cover the various methods for synthesis of phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate esters of phosphate. Accordingly, we refer the reader to key reviews in this area which serve as useful springboards to the primary synthetic literature. In general, both enzymatic and chemical synthetic methods abound. A key consideration in most protocols is the necessity to synthesize stereochemically pure compounds, or alternatively, be able to resolve them chromatographically. Reviews by Eckstein49 and Frey6 provide a comprehensive overview of the chemical and enzymatic methods for synthesis of phosphorothioate analogues of nucleotides, cyclic nucleotides, phospholipids, and several other phosphate esters of biological interest. The abbreviated discussion that follows extends the synthetic overview to the synthesis of phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate oligonucleotides.

Stereospecific incorporation of nonbridging sulfur substituents into the backbone of DNA or RNA has become fairly routine. Pure (Rp) phosphorothioate linkages in DNA or RNA can be prepared enzymatically using pure nucleoside Sp-α-thio triphosphates and a polymerase enzyme, where the reaction goes with inversion of configuration 50,51. Chemical synthesis of racemic phosphorothioate linkages in oligonucleotides involves substituting the oxidation step of phosphoramidite based solid-phase synthesis with a sulfurization step using 3H-1,2-benzodithiol-3-one 1,1 dioxide52. This approach requires post-synthetic separation of the Rp and Sp diastereomers by C-18 reversed-phase HPLC, and configurational analysis of the product using enzymatic methods53. Although this separation usually works well for oligonucleotides shorter than about twenty nucleotide units, it may be problematic for certain nucleotide sequences or for longer oligonucleotides. An alternative approach that provides a stereochemically pure linkage for any length oligonucleotide is the block coupling of a diastereomerically pure dinucleoside phosphorothioate 3′-phosphoramidite precursor during solid phase oligonucleotide synthesis54.

Incorporation of a 5′-bridging sulfur substituent in an oligonucleotide context was originally reported by Mag et al55, and a modified procedure was subsequently reported by Burgin 56,57. Both procedures involve preparation of a 5′-(S-trityl)-mercapto-5′-deoxynucleoside-3′-O-(2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropyl) phosphoramidite which is used directly in solid phase oligonucleotide synthesis with conventional nucleoside phosphoramidites. This synthesis requires careful purification of the full length oligonucleotide product because extension from the site of sulfur incorporation proceeds in much poorer yield than standard phosphoramidites58.

Several methods have been reported for the solid phase synthesis and purification of stereoisomerically pure methylphosphonate oligonucleotides. Methods are similar to the general approaches described above for phosphorothioates including the chromatographic separation of the diastereomers59, block coupling of diastereomerically pure dinucleoside methylphosphonates60,61, and kinetic resolution based on phosphorus III chemistry62.

5.2 Key Considerations in Binding and Kinetic Measurements

The first considerations when performing a mutational or chemical substitution measurement is the accuracy and precision of the binding or kinetic measurements and the actual magnitude of the measured effect. Because mutational and substitution effects are based on ratios of rate constants or equilibrium constants, the relative error in the ratio is determined by the square root of the sums of the squares of the relative errors in each kinetic or thermodynamic constant. Thus, measurement errors are magnified in the ratio. Compounding with the intrinsic measurement error is the enormous range of values for mutational and chemical substitution effects. For instance, effects of methyl or sulfur substitution as small as unity, and as large as 100,000-fold have been measured (see examples that follow). Obviously, a crude assay with fairly large errors can provide useful results if the effect is on the high side of this range, but very good continuous kinetic assays or robust binding measurements are needed to measure effects in the range 2 to 10-fold.

Rigorous interpretation of mutational and thio effects also requires consideration of the rate-limiting steps of the steady-state reaction (eq 8–10).

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

For instance, if product release (k3) is severely rate-limiting for kcat measurements with the oxygen substrate or with the wild-type enzyme, but the chemical step (k2) is rate-limiting for the substituted substrate or mutant enzyme, then the measured mutational or substitution effect will be significantly attenuated due to a change in rate-limiting step upon substitution or mutagenesis. This assertion assumes that the largest effect is on the chemical step (which is often true) and that the product release step has a smaller or nonexistent mutational or substitution effect. Under these conditions it may be helpful to measure the effects on kcat/Km because this constant is unaffected by the product release step (k3), and only reports on the kinetic steps between substrate binding (k1) and the first irreversible step of the enzymatic reaction63. In many cases the first irreversible step involves the chemical step (k2), allowing measurement of the full mutational or substitution effect on this kinetic constant. It must be kept in mind, however, that the full effect on the chemical step using kcat/Km conditions will only be realized when k−1≫ k2. This is identical to the essential requirement for measuring full (intrinsic) kinetic isotope effects, termed a small forward commitment to catalysis by Cleland64. A different approach that is frequently used is to employ an alternative substrate that is less reactive than the normal substrate, thus making the chemical step fully rate limiting. Alternatively, the mutational or substitution effect can be measured using single turnover conditions (i.e. where [E] ≫ [S]). Once again, under these conditions product release is not part of the overall rate expression (i.e. kobsd = k2), and very often, the full mutational or substitution effect on the chemical step is realized using such conditions. However, it should be pointed out that if the rate limiting step involves a conformational step preceding the chemical step, the effects will still be masked using single turnover conditions. The bottom line is this: a detailed knowledge of the reaction mechanism and rate limiting steps are critical for any study involving quantitative mutagenesis or chemical substitution measurements.

6. Examples Using Chemical Modification of Phosphate Esters Alone

Before introducing enzyme examples where mutagenesis and chemical substitution have been used in combination it is informative to survey some representative studies where phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate substitution have been used in isolation. The purpose here is to gain a feeling for the magnitude of the effects in several different systems and see some of the limitations that can be ameliorated by combining substitution with mutagenesis. The thio effects and methyl effects for all of the systems discussed in sections 6 and 7 are compiled in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Combined energetic effects of enzyme mutagenesis and substrate thio substitution at nonbridging phosphoester oxygens (kcal/mol)

| System | ΔΔGbind a | ΔGcbind b | ΔΔGchem | ΔGcchem | Ref | System | ΔΔGchem | ΔGcchem | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Protein | 66 | UDG | 126 | ||||||

| Rp | −0.7 to 1.0 | WT | |||||||

| Sp | −0.5 to 0.7 | +1 Rp | −1.3 | ||||||

| +1 Sp | −2.5 | ||||||||

| EcoRI | 54, 70 | −1 Rp | −0.6 | ||||||

| −1 Sp | −0.7 | ||||||||

| Clamp | −2 Rp | −2.1 | |||||||

| Rp | −0.7 | −0.1 | −2 Sp | +0.5 | |||||

| Sp | −0.9 | −0.7 | |||||||

| Central | S88A | ||||||||

| Rp | +0.3 | −0.4 | +1 Rp | −1.7 | +0.4 | ||||

| Sp | −1.7 | +0.2 | +1 Sp | −0.5 | −2.0 | ||||

| −1 Rp | −1.6 | +1.0 | |||||||

| EcoRV | 72 | −1 Sp | −1.8 | +1.1 | |||||

| Rp | 0.5 to 6.1 | ||||||||

| Sp | 1.3 to 10 | S189A | |||||||

| +1 Rp | −1.2 | −0.1 | |||||||

| vTopo | 84, 102 | +1 Sp | −0.8 | −1.7 | |||||

| −1 Rp | −0.4 | −0.1 | |||||||

| WT | −1 Sp | −0.6 | −0.1 | ||||||

| Rp | −1.7 | −3.7 | |||||||

| Sp | −0.6 | −2.6 | Phospholipase-C | 131–134 | |||||

| R130A | |||||||||

| Rp | −1.4 | −0.3 | −1.3 | −2.4 | WT | ||||

| Sp | 0 | −0.6 | +0.3 | −2.9 | Rp | −2.2 | |||

| R130K | Sp | −7.5 | |||||||

| Rp | −1.3 | −0.4 | −1.4 | −2.3 | D33N | ||||

| Sp | −1.0 | +0.4 | 0 | −2.6 | Rp | −1.0 | −1.2 | ||

| K167A | Sp | −3.0 | −4.5 | ||||||

| Rp | −0.7 | −1.0 | −3.1 | −0.6 | D33A | ||||

| Sp | +0.4 | −1.0 | −3.0 | +0.4 | Rp | −2.7 | +0.5 | ||

| R223A | Sp | −3.7 | −3.8 | ||||||

| Rp | −1.4 | −0.3 | −1.6 | −2.1 | R69K | ||||

| Sp | 0 | −0.6 | −1.9 | −0.7 | Rp | −2.1 | −0.1 | ||

| H265A | Sp | −2.0 | −5.5 | ||||||

| Rp | −2.1 | −1.6 | |||||||

| Sp | −2.8 | +0.2 | Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase | 44 | |||||

| RNAse T1 | 79 | WT | |||||||

| Ps | −5.0 | ||||||||

| WT | W354A | ||||||||

| Rp | −6.7 | Ps | −4.5 | −0.5 | |||||

| Sp | −0.2 | D356A | |||||||

| Y38F | Ps | −5.4 | +0.4 | ||||||

| Rp | −6.2 | −0.5 | R409K | ||||||

| Sp | +1.6 | −1.8 | Ps | −3.2 | −1.8 | ||||

| H40A | Q446A | ||||||||

| Rp | Ps | −3.8 | −1.2 | ||||||

| Sp | −1.0 | +0.8 | Q450A | ||||||

| E58A | Ps | −2.7 | −2.3 | ||||||

| Rp | −0.8 | − 5.9 | |||||||

| Sp | −1.0 | +0.8 | |||||||

| H92Q | |||||||||

| Rp | |||||||||

| Sp | −0.9 | +0.7 | |||||||

| F100A | |||||||||

| Rp | −3.0 | −3.7 | |||||||

| Sp | −0.9 | +0.7 |

The corresponding free energy changes for the substitution effects were calculated using ΔΔGbind = −RT ln(KDox/KDs) and ΔΔGchem = −RT ln(kox/ks) for the binding and chemical steps respectively (T = 25°)..

In the examples where both enzyme mutagenesis and phosphorothioate modifications were performed, the coupling energies for the interaction of an enzyme side chain with a nonbridging oxygen were determined using the equations: ΔGcbind = ΔΔGwtbind − ΔΔGmutbind and ΔGcchem = ΔΔGwtchem − ΔΔGmutchem. A negative coupling energy is expected for a direct interaction with an enzyme side chain and a nonbridging oxygen. The coupling energies that correspond to a direct interaction between a nonbridging oxygen and an enzyme side chain, as judged by x-ray crystallography, are shown in bold in the Table.

Table 2.

Combined energetic effects (kcal/mol) effects of enzyme mutagenesis and substrate methyl substitution of nonbridging phosphoester oxyqens

| System | ΔΔGbind a | ΔΔGchem | ΔΔGcchem b | Ref | System | ΔΔGbind | ΔΔGchem | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-Protein | 65 | UDG | 125 | |||||

| Rp | −0.7 to 3.4 | WT/Substratec | ||||||

| Sp | −0.4 to 2.3 | +2 fast | −0.4 | |||||

| vTopo | 104,105 | +2 slow | −0.4 | |||||

| +1 fast | +3.6 | |||||||

| WT | +1 slow | +2.3 | ||||||

| Rp | −4.8 | −1 fast | +5.0 | |||||

| Sp | −3.2 | −1 slow | +1.5 | |||||

| R223A | −2 fast | +4.5 | ||||||

| Rp | +0.1 | −4.9 | −2 slow | +4.8 | ||||

| Sp | +3.1 | −6.3 | ||||||

| R223K | WT/TS Analogd | |||||||

| Rp | −4.9 | +0.1 | +1 fast | +6.3 | ||||

| Sp | −2.0 | −1.2 | +1 slow | +6.3 | ||||

| H265A | −1 fast | +5.8 | ||||||

| Rp | −4.7 | −0.1 | −1 slow | +3.0 | ||||

| Sp | +0.1 | −3.3 | −2 fast | +7.2 | ||||

| −2 slow | +7.3 |

The corresponding free energy changes for the substitution effects were then calculated using ΔΔGbind = −RT ln(KDOX/KDMe) and ΔΔGchem = −RT ln(kOX/kMe) (T = 25°). The Rp and Sp designation refer to the respective stereoisomer created at the substitution site upon methyl modification.

In the topoisomerase example, the coupling energies for the interaction of an enzyme side chain with a nonbridging oxygen were determined using the equations: ΔGcbind = ΔΔGwtbind − ΔΔGmutbind, and ΔGcchem = ΔΔGwtchem − ΔΔGmutchem.

In the UDG system, the designation fast and slow corresponds to the faster and slower migrating diastereomers during HPLC elution of the methylphosphonate substituted substrate. See Figure 22 for the numbering key.

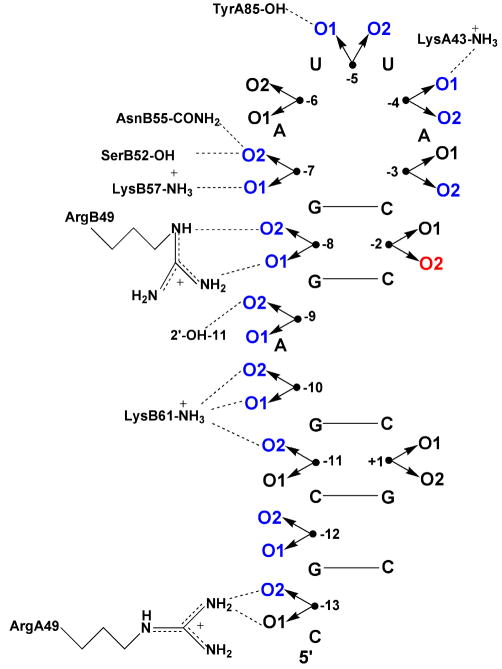

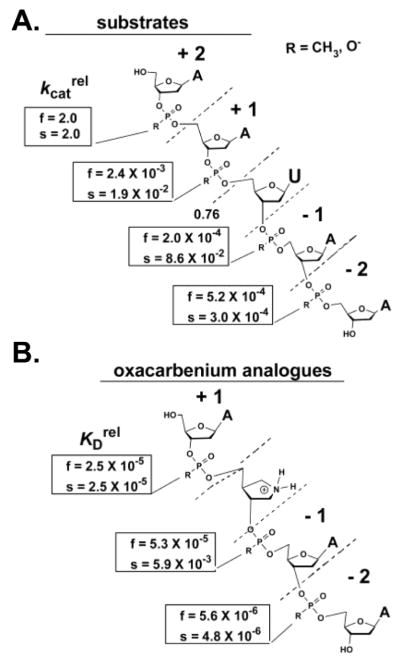

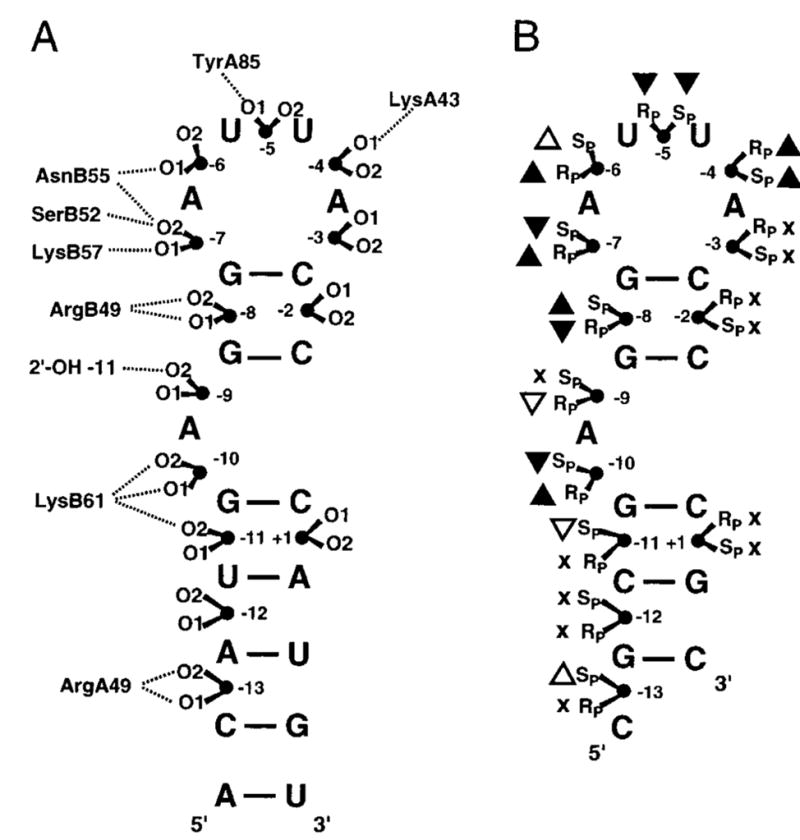

6.1 Protein-RNA Binding Reactions

Uhlenbeck and colleagues have performed a very comprehensive study of the effects of phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate substitution on the binding interaction of MS2 coat protein with a small RNA hairpin65,66. In this work, a single phosphorothioate or methylphosphonate linkage was introduced at 13 different positions in the RNA, providing a substantial database of measured effects. The value of this study was greatly increased because a high resolution crystal structure was also available for the complex67, which allowed direct comparison of the substitution effects with structural data as summarized in Figure 8 for the phosphorothioate substitutions. Generally speaking, there was an excellent correlation between the structure and modification data. At all of the eight phosphates where a contact was observed in the structure at least one of the two sulfur diastereomers showed a binding effect, and at the four positions where no contact was observed, the binding was unchanged by sulfur substitution. Therefore, based on these findings phosphorothioate substitution appears to be a reliable method for identifying protein-RNA backbone contacts.

Figure 8.

Interactions between MS2 coat protein and RNA 56. (A) Representation of the protein-phosphate contacts observed in the crystal structure of the complex of MS2 coat protein bound to a 21-nucleotide RNA hairpin. The prefixes A and B specify the amino acids in the two monomers of the dimeric coat protein. O1 and O2 correspond to the Rp and Sp phosphorothioate diastereomers. (B) Thio effects on binding. Black triangles indicate the positions with the largest thio effects of binding; upward and downward pointing triangles indicate stronger and weaker binding for the phosphorothioate RNA, respectively. Small effects are indicated by white triangles, and sites where binding was unaffected by substitution are marked with an x.

In this study, the energetic effect of a single phosphorothioate substitution was in the range 0.4 to 1 kcal/mol, reflecting modest 2 to 5-fold changes in binding affinity. A key observation was that there was no apparent difference in the thio effect when the interacting group was a hydrogen bond donor or an ionic contact. Surprisingly, substitution at many positions gave rise to an increase in binding affinity for one isomer, while the other isomer showed either no change, or a similar change in the same or opposite direction. Many of these diverse effects were rationalized by invoking steric effects, hydrophobic (solvation) effects, or differences in the charge or bond length of P-S relative to P-O bonds (see section 2). The authors also suggested that when a complex series of hydrogen bonds is formed between the protein and the RNA backbone, it is not possible to rationalize the substitution data based on the observed structural interactions. Thus, substitution of nonbridging atoms that form simple hydrogen bonds or ionic interactions with the protein generally give rise to energetic effects that are most easily reconciled with structural information.

Methylphosphonate substitution in the same system resulted in even better agreement with the structural observations (Figure 9) 65. All phosphates that were in proximity to the protein showed a weaker binding affinity when substituted with a methylphosphonate linkage, and control positions showed no change. In two positions a methylphosphonate isomer altered the binding affinity where no interaction was observed in the crystal structure, which was attributed to changes in the flexibility of the hairpin arising from the substitution. The authors concluded that methylphosphonate substitution was superior to phosphorothioate substitution because it nearly always decreases the binding affinity, whereas phosphorothioate substitution either strengthened or weakened binding interactions in unpredictable ways (see above). A useful advantage of the methylphosphonate effects was that they were typically much larger than the sulfur substitution effects, falling in the range 2 to 500-fold. In addition, it was noted that the effects were not stereospecific for 5 out of 7 linkages that were in direct contact with the enzyme. This is consistent with the expectation that removal of the methyl group removes a hydrogen bond acceptor and also abolishes the negative charge of the remaining nonbridging oxygen, negating favorable interactions at both positions. In conclusion, these studies largely validate the utility of both phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate substitution for identifying important binding contacts, but as will be detailed below, the combined mutagenesis and substitution methodology increases the information content of the substitution effects.

Figure 9.

Changes in MS2 protein-RNA binding affinity arising from methylphosphonate substitution57. Oxygens where substitution strengthens, weakens or has no effect on binding are shown in red, blue and black, respectively.

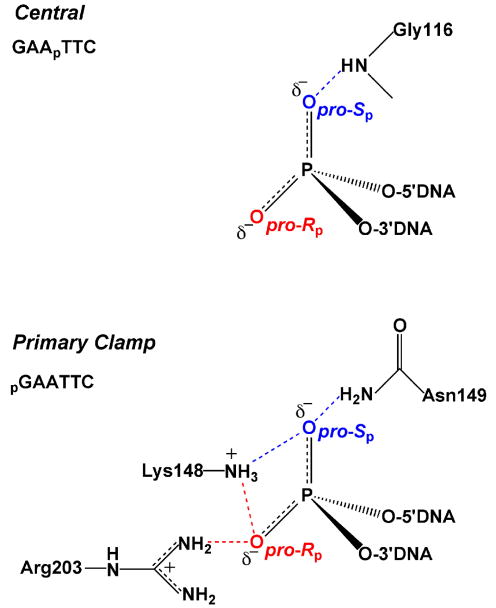

6.2 Reactions With DNA: EcoRI and EcoRV Restriction Enzymes

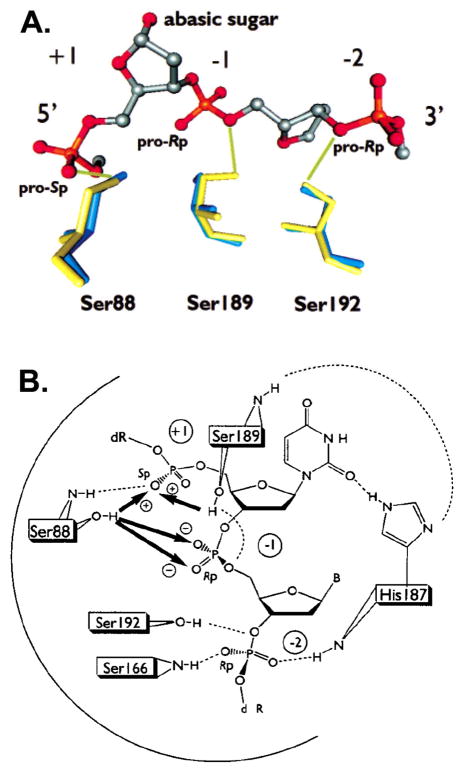

Phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate substituted DNA has been used extensively to study the site-specific DNA binding and phosphodiester hydrolysis reactions of several DNA restriction endonucleases. The approach was first explored by Eckstein and colleagues68,69, and later applied by others to the prototypic restriction endonucleases EcoRI and EcoRV53,54,70. Jen-Jacobson and workers probed the ground state binding contacts between EcoRI and the central phosphate (p) of its recognition sequence G↓AApTTC as well as the “primary clamp” phosphate pG↓AATTC using stereospecific phosphorothioate linkages (the arrows mark the phosphodiester linkage that is cleaved during the hydrolysis reaction)54,70. These studies were strengthened by the availability of a crystal structure of the protein-DNA complex which showed that these two phosphates have very different interactions with the enzyme71 (pdb code 1ERI) (Fig. 10). The pro-Sp oxygen of the central phosphate accepts a hydrogen bond from the backbone NH of a glycine residue (N → O distance of 2.9 Ǻ), but the other oxygen of this linkage does not interact with the protein at all. An entirely different arrangement prevails for the primary clamp phosphate which was found to be completely engulfed by protein interactions. The pro-Rp oxygen of this phosphate is directed towards the major groove and contacts the guanidino group of Arg203 and the side chain amino group of Lys148. The pro-Sp oxygen receives hydrogen bonds from the side chain of Asn149 and the main chain amide of Lys89. In addition, these primary contact residues are connected via hydrogen bonds to other residues that contact the DNA backbone and bases or other enzyme residues involved directly in catalysis. The very different interactions of the enzyme with these two linkages make an interesting case study in the interpretation of thio effects as detailed below.

Figure 10.

Interactions of EcoRl with the central and primary clamp phosphates as observed in the crystal structure 1ERI.

As observed with the MS2 coat protein-RNA complex, both increases and decreases in ground state binding affinity in the range −0.7 to +1.0 kcal/mol were observed upon sulfur substitution at these two linkages of the EcoR1 site. Substitution at the noninteracting Sp position of the central phosphate gave rise to 20-fold tighter binding, while the interacting Rp substitution led to 2-fold weaker binding. This unanticipated effect was rationalized by the proposal that Sp sulfur substitution increased the P-O bond order of the remaining P-O bond, thereby shortening it, increasing the hydrogen bond distance by 0.06 Ǻ, and resulting in a more favorable hydrogen bond distance of ~2.8 Ǻ between the Rp oxygen and the glycine NH. Accordingly, the weaker binding observed upon substitution of the pro-Rp oxygen with sulfur was attributed to steric conflicts arising from the longer P-S bond (an increase of 0.6 Ǻ over the P-O bond)6,15. However, these explanations are somewhat unsatisfying. It is not clear why a small 0.06 Ǻ decrease in hydrogen bond distance, and in addition, ablation of negative charge, would give rise to a substantial 20-fold increase in affinity. Moreover, a 0.6 Ǻ increase in P-S bond length with the Rp substituent would be expected to severely disrupt hydrogen bonding, yet only a small 2-fold damaging effect is observed. Outcomes such as this may benefit from additional mutagenesis experiments, or perhaps measurements of methylphosphonate effects, to provide a more sound understanding of the interactions.

The Rp and Sp substitutions at the primary clamp phosphate linkage of the EcoRI recognition sequence gave rise to similar three and five fold decreases in binding affinity as seen for the Rp-position of the central phosphate. This was surprising because the central and primary clamp phosphate groups make completely different contacts with the protein (see above). The small magnitude of these effects makes them difficult to interpret in terms of structure, but the authors suggested that the effects arose from a combination of changes in charge and bond orders at the substituted position, which in turn led to disruption of the other interaction due to the intimate coupling to the recognition interface.

Thio effects on the chemical step in EcoRI catalysis were measured by substituting the central and primary clamp phosphate oxygens54,70. These measurements, which were performed under single turnover conditions, represent indirect effects on the activation barrier, because the central and primary clamp phosphates are not the sites of cleavage by EcoRI. With both substituted phosphates, one isomer showed no effect and the other produced a small two to three-fold rate decrease. The generally small or absent thio effect on the activation barrier, and the observed ground state stabilization of as much as 1.7 kcal/mol with some substitutions, indicates that thio substitution has approximately equal energetic effects in the ground state and transition state in this system. In general, the small thio effects and complex interaction network of EcoRI recognition make definitive conclusions about these interactions quite tenuous.

Connolly and co-workers synthesized a set of DNA dodecameric oligonucleotides containing the recognition sequence for EcoRV restriction endonuclease and introduced stereospecific phosphorothioate linkages at the central nine positions, including the scissile linkage72. The thio effect results were then compared with the crystal structure of the enzyme-DNA complex73. The important phosphates, as assessed by thio effect measurements, comprised GACGp4Ap5Tp6↓Ap7Tp8Cp9GTC of the dodecamer. Substitution at phosphate linkages p4, p5, p8 and p9 produced five to 30-fold decreases in kcat and, in general, 1.5 to 10-fold lower Km values. Much greater deleterious effects were observed at the scissile phosphate p6 and the adjacent phosphate p7: both phosphorothioate isomers at the scissile position were so damaging that rate measurements were precluded, and Sp substitution at p7 also abolished catalysis, while Rp substitution had no effect. In the case of the scissile phosphate, the effects were attributed to cooperative disruption of a network of interactions for the Rp isomer, and in the case of the Sp isomer, to reduced Mg2+ binding. The disruption of metal binding was supported by crystallographic studies which show that the pro-Sp oxygen is one of the ligands to the catalytic Mg2+. Thus, the observed structural interactions provide convincing support for the interpretation of the large Sp thio effects because sulfur is a poor ligand for hard metals like Mg2+12. For the p7 phosphate, the low activity of the Sp phosphorothioate substituted substrate was attributed to a role for the pro-Rp oxygen of the p7 phosphate as a general base to deprotonate the catalytic water. The profound activity decrease is thus brought about by localization of the negative charge on Sp sulfur, and increased double bond character of the remaining Rp oxygen, which significantly lowers its pKa such that it cannot serve as an efficient general base. This interpretation was supported by methylphosphonate substitution at the same phosphate linkage of 17 different restriction enzymes74, where only five enzymes were found not to be significantly inhibited by this substitution. Although these findings suggest a role for the pro-Rp oxygen as a general base, it is not clear how a nonbridging phosphodiester oxygen with a pKa ~ 1.5 in water could serve as a efficient general base unless the enzyme environment is highly desolvated or a local negative potential is increasing its basicity.

7. Examples Combining Chemical Modification and Mutagenesis

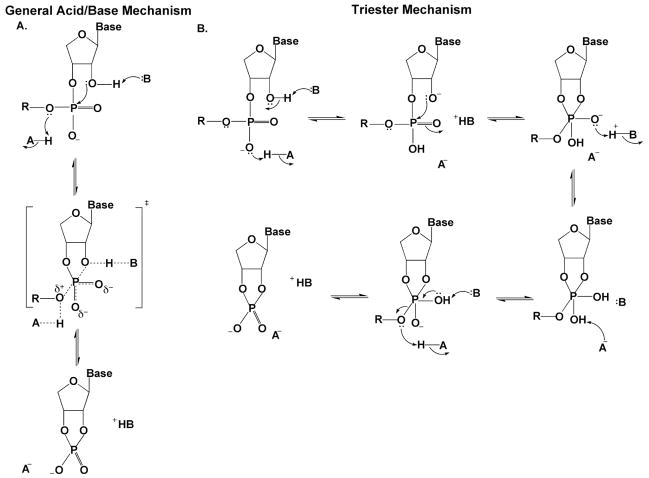

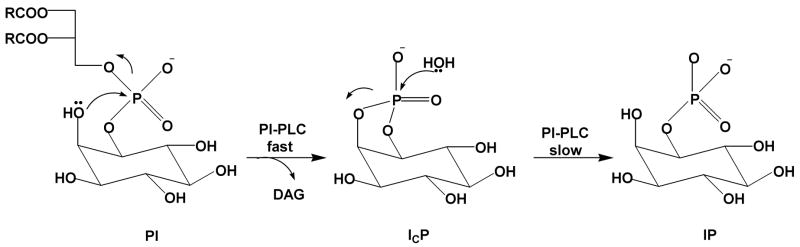

7.1 RNase T1

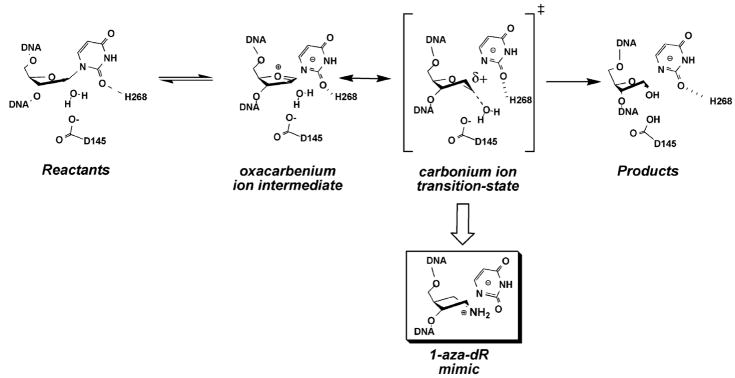

Despite extensive research, the detailed series of chemical events in ribonuclease (RNase) catalyzed phosphoryl transfers are still debated75–78. Enzymes such as RNase A and RNase T1 cleave phosphodiester bonds in RNA using the 2′ OH of the RNA as the initial nucleophile to form a 2′, 3′ cyclic phosphodiester intermediate that is subsequently hydrolyzed (Figure 11). Two general mechanisms for formation of the cyclic phosphate intermediate have been proposed. The first involves concerted general-acid base catalysis by two conserved histidine residues: the base deprotonates the 2′OH, and the acid protonates the 5′-OH leaving group (Figure 11A). The second type of mechanism is distinguished by initial proton transfer to a nonbridging oxygen, which is then followed by 2′-OH attack. In the second mechanism, preequilibrium protonation of the nonbridging oxygen makes the second nucleophilic addition step triester-like (Figure 11B). For RNase A, small nonbridging thio effects have been interpreted in favor of the concerted acid-base mechanism75, because nucleophilic substitution at phosphate triesters is expected to have a thio effect of around 100 (Figure 6).

Figure 11.

Proposed mechanisms for RNase T1 catalysis. (A) General acid-base mechanism66. (B) Triester mechanism 67.

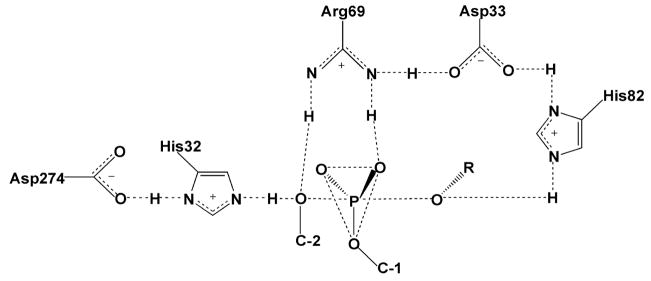

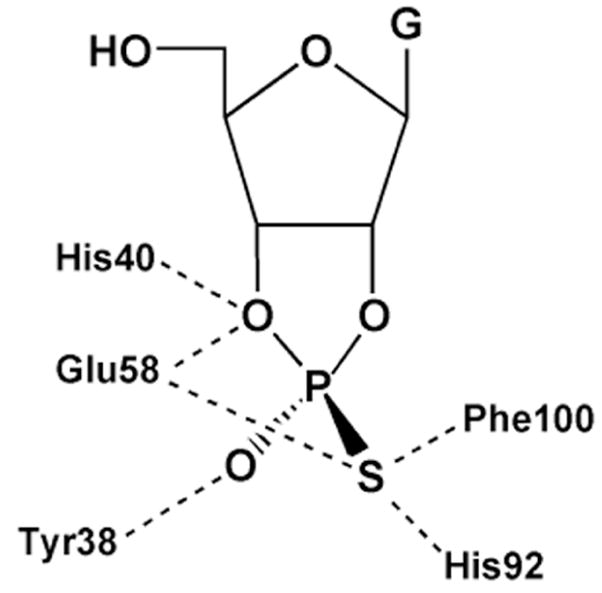

7.1.1 Nonbridging Phosphorothioate Substitution and RNase T1 Mutagenesis

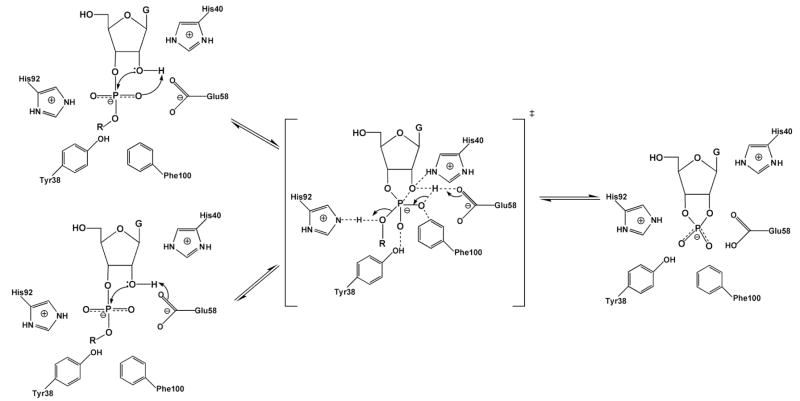

Steyaert and colleagues have investigated the nonbridging thio effects for RNase T1, and in conjunction with mutagenesis, concluded that, unlike RNase A, this enzyme uses a triester-like mechanism79. The active site of RNase T1, in complex with exo (Sp) 2′, 3′-cGMP(S), which is the product of the transphosphorylation of Sp Gp(S)U, is shown in Figure 12. The structure suggests close proximity of the aromatic ring of Phe100 and and the side chain of Glu58 to the Sp sulfur, but not the Rp oxygen. In addition, both His40 and Glu58 are within hydrogen bonding distance of the 2′-oxygen of the cyclic phosphate intermediate, indicating that His40 would be the general base if a concerted general acid–base mechanism is followed as suggested for RNase A. Consistent with the structure, the authors found that Sp Gp(S)U had an enormous thio effect on kcat/Km of 88,500, whereas the Rp form showed a negligible effect of 1.580. In addition, no thio effect on binding was observed indicating that the perturbed interactions were in the transition state. The Sp thio effect on kcat/Km is one of the largest ever reported for a non-metal assisted reaction, and is only eclipsed by the Sp thio effect for phosphatidylinositol-specific phosholipase C, which interestingly, proceeds by a similar cyclic phosphate mechanism (see section 7.4). The large thio effects in these two related systems suggests that Sp sulfur substitution has an unusually deleterious effect in the transition state for formation of cyclic phosphate intermediates. This could arise from highly specific electronic or geometric constraints of this transition state in the active sites of enzymes.

Figure 12.

Active site interactions of RNase T1 with exo (Sp) 2′, 3′-cGMP(S), the product of transphosphorylation of Sp Gp(S)U.

As anticipated, mutation of the residues that were thought to directly interact with the pro-SP oxygen of RNase T1 (F100A and E58A) resulted in ~102 to 104-fold decreases in the SP thio effect, with the largest reduction seen with E58A. Mutation of other residues produced either small changes in the thio effect, or for the H92Q and H40A mutations, the activity was too low to be detected with the Sp sulfur substrate. (A lower limit thio effect of > 330 for both histidine mutants can be estimated from the detection limits of the assay). The diminished thio effect for E58A corresponded to a coupling energy of −5.9 kcal/mol (Table 1). Based on the large thio effects and the mutagenesis results, these authors proposed a triester-like transition state for formation of the cyclic intermediate involving a three-centered hydrogen bond with the pro-Sp oxygen and Glu-58 (Figure 13). The authors argued that the lower proton affinity of sulfur impaired proton transfer. However, alternative explanations such as stereospecific steric effects on catalysis are not excluded. Furthermore, the similarly large Sp thio effect for cyclic phosphate formation with phosphatidylinositol-specific phosholipase C (Section 7.4), was reconciled with a simple general acid-base mechanism without invoking protonation to form a triester-like transition state. One lesson of enzymatic thio effects is that it is virtually impossible to use thio effects alone to define transition state structure because of unknown steric and electronic requirements in the transition state that overwhelm the simple trends from solution reactions (Figure 6).

Figure 13.

Triester-like transition state for formation of the cyclic intermediate in the RNAse T1 reaction involving a three-centered hydrogen bond with the pro-Sp oxygen and Glu-5870.

7.2 Vaccinia DNA Topoisomerase I (vTopo)

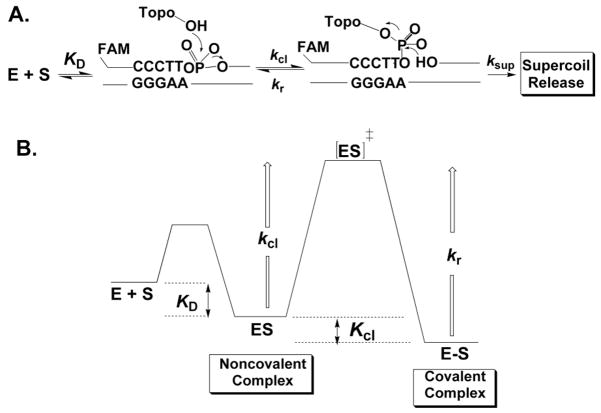

The vaccinia virus type IB DNA topoisomerase (vTopo) is a well-studied enzyme where both phosphorothioate and methylphosphonate chemical modifications of the DNA backbone have been combined with enzyme mutagenesis to reveal a detailed interaction map between the enzyme and the DNA substrate. The type IB topoisomerase reaction is freely reversible and occurs by four discrete steps (Figure 14). These steps involve i) non-covalent binding of the enzyme to the DNA with a dissociation constant KD, ii) cleavage of a single DNA strand leading to formation of a covalent 3′-phosphotyrosine linkage and a free 5′-hydroxyl leaving group(kcl), iii) release of superhelical tension by a strand rotation mechanism (ksup), and iv) religation of the DNA break by attack of the 5′-hydroxyl nucleophile (kr). The vTopo enzyme is unique in that it shows high specificity for cleavage at the pentapyrimidine recognition sequence 5′ (C/T)+5C+4C+3T+2T+1p↓N−1 (the arrow indicates the site of covalent attachment). The binding, cleavage and religation events are most easily studied using synthetic oligonucleotide DNA substrates of length 18 to 40 base pairs, and rigorous methods have been developed to measure each step of the vTopo reaction58,81–84,85. Alanine scanning of about 142 amino acids in vTopo has been performed to identify essential catalytic residues86. From this study, only seven amino acids were found to decrease enzyme DNA cleavage activity by greater than 100-fold: Arg130 (105-fold), Gly132 (102-fold), Tyr136 (103-fold), Lys167 (105-fold), Arg223 (105-fold), His265 (105-fold) and Tyr274 (>105-fold) (the active site nucleophile). It is important to note that five of the six essential amino acids are strictly conserved in every member of the eukaryotic type IB enzyme family (the exception is Tyr136)87.

Figure 14.

Topoisomerase reaction cycle. A) The three steps in the vTopo reaction involve DNA binding, reversible DNA backbone cleavage described by the rate constants kcl and kr, and for supercoiled DNA substrates, supercoil relaxation while the enzyme is covalently attached to the phosphodiester backbone (ksup). Relaxation occurs by a “free rotation” mechanism in which the noncovalently bound end swivels around the helix axis. The number of supercoils that are removed after a single cleavage event is dependent on the ratio ksup/kr: if kr is rapid there is no opportunity for DNA rotation before the strand is resealed. B) Free energy reaction coordinate profile depicting the thermodynamic and kinetic barriers of the reaction. The rate constants and equilibrium constants refer to the free energy barriers defined by K = exp (−ΔG/RT) and k = (kBT/h) exp(−ΔG‡/RT).

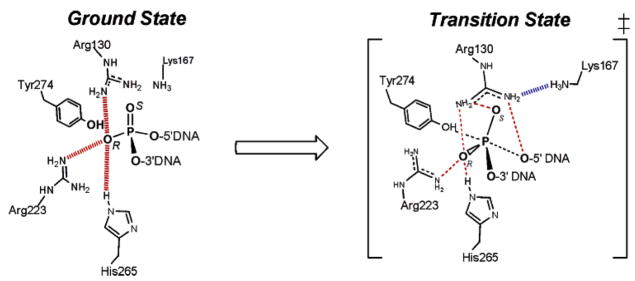

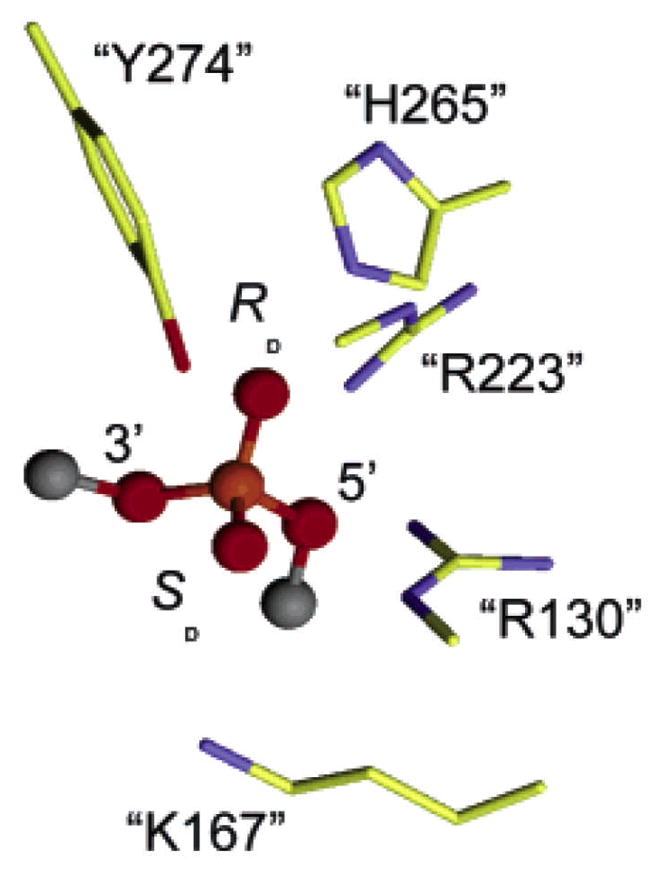

Although the vTopo protein-DNA complex has been found to be refractory to crystallization, several X-ray structures of DNA bound to the highly homologous human topoisomerase IB have been solved, both in the noncovalent and phosphotyrosine covalent complexes88–93. These structures revealed that the amino acid equivalents of Arg130,44 Argl30, Lysl67, Arg223 and His265 of the vaccinia enzyme were near the scissile phosphate (Figure 15). From these structural studies, Arg130 was observed to contact both of the nonbridging oxygens, whereas Arg223 interacted only with pro-Rp oxygen. However, the roles of His265 and Lys167 were ambiguous because they were either too far away from the scissile phosphate to assist catalysis (Lys167), or roughly equidistant from both the pro-Rp nonbridging oxygen and the 5′–O leaving group (His265). Thus, these crystallographic efforts left key questions unresolved, including the exact roles of Lys167 and His265, and identity of the general acid catalyst of leaving group expulsion. Thus, alternative approaches to obtain structural information for the various catalytic intermediates and transition states became quite important to increase the understanding of this enzyme reaction.

Figure 15.

Interactions in the vTopo Michaelis complex with DNA. The interactions are from the crystal structure of the closely related human topoisomerase IB (pdb colde 1EJ9) and the residue numbering corresponds to vTopo.

7.2.1 Bridging Phosphorothioate Substitution and vTopo Mutagenesis

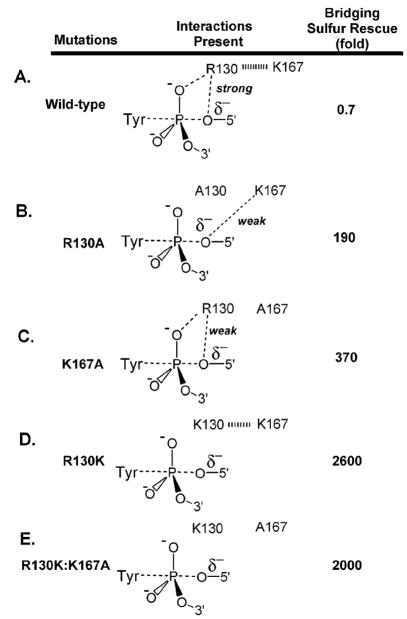

To determine the identity of the general acid catalyst, Shuman and coworkers determined the activity effects of 5′ bridging sulfur substitution at the scissile phosphate for the wild type enzyme and several alanine mutants of the enzyme (Table 3)94,95. The expectation was that mutation of the true general acid to alanine (i.e. a residue that does not posses a proton donor function) would significantly reduce the activity of topoisomerase toward the oxygen substrate but not the sulfur substrate. The activity rescue of the mutant enzyme by a 5′-bridging sulfur provides strong evidence that the mutated residue is the general acid functionality, because a 5′ sulfur leaving group does not need assistance from a general acid because of its low pKa (see section 3). Thus, a “5′-S rescue” of much greater than unity (eq 11)

Table 3.

Bridging Thio Effects (TEB) on vTopo DNA Cleavagea

| Enzyme | TEB |

|---|---|

| Wt | 0.7 |

| H265A | 1.8 |

| R130A | 190 |

| R130K | 2,600 |

| K167A | 370 |

| R130K:K167A | 2,000 |

| R223A | 0.8 |

| (11) |

provides a strong indicator for the identity of the general acid catalyst. In this equation, TEmut and TEwt are defined as kOX/kS for the mutant and wild-type enzymes, respectively. In addition to P-S bridging linkages, it should be noted that P-N bridging linkages of phosphoamides can either be intrinsically less or more reactive than the corresponding P-O linkage depending on the relative pKa values for the leaving groups96–98, and possible stereoelectronic differences between these reactions99,100. We are not aware of any studies of enzyme catalyzed reactions that have employed substrates with P-N linkages in combination with mutagenesis.

In this work, the R223A and H265A mutants showed little or no 5′-S rescue indicating that neither of these residues were the general acid (Table 3). In contrast, the R130A and K167A enzymes exhibited large 5′-S rescues of 190 and 370, respectively. Interestingly, the R130K mutant showed the largest 5′-S rescue (2600-fold). To explain these observations, Shuman and coworkers suggested that Arg130 and Lys167 interacted with each other during the proton donation step, thereby forming a proton relay chain95. Thus, the direct proton donor to the 5′-oxygen remained elusive in these studies (i.e. R130→K167 → 5′-O vs K167→R130→5′-O). Of the two possibilities, Shuman et al suggested that Lys167 was the direct proton donor, with Arg130 serving an indirect role. This tentative assignment was based on the fact that Lys167 was located within hydrogen bonding distance (3.2 Å) of the 5′-OH of the cleaved strand in the cocrystal structure of the related enzyme Flp recombinase101. In this mechanism where Lys167 is the direct proton donor, Arg130 was proposed to lower the pKa of Lys167 through an electrostatic mechanism. However, the choice of Lys167 as the direct proton donor does not explain the 10-fold larger rescue observed for the R130K mutant as compared to K167A or R130A. As described below, the nonbridging thio effect measurements of Nagarajan and Stivers suggested a plausible mechanism that accounts for all of these findings.

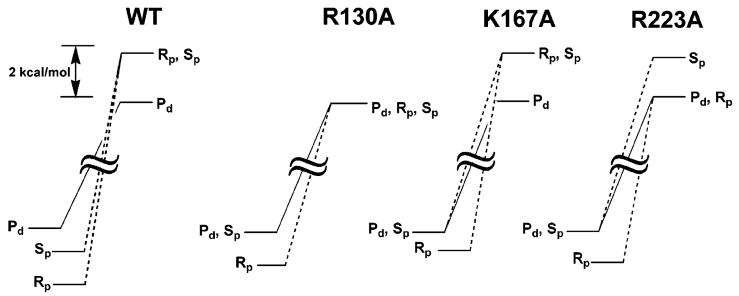

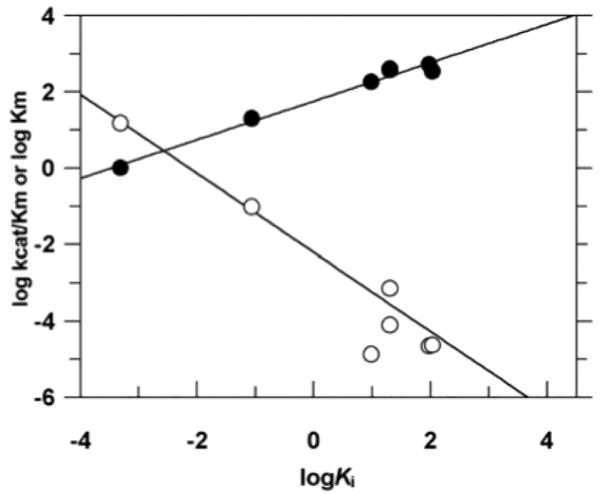

7.2.2 Dissecting the Energetics of Nonbridging Phosphorothioate Substitution with vTopo Mutants

Two comprehensive studies examined the effects of mutagenesis and nonbridging phosphorothioate substitution on the vTopo reaction84,102., A key aspect of this work was the measurement of both binding and kinetic effects for each substitution and mutant, providing the necessary energetic measurements to understand how enzyme interactions with the scissile phosphate changed between the ground state and transition state as shown in Figure 16 for the wild-type, R130A, K167A and R223A enzymes. In this analysis, the thio effects (TE) on binding and cleavage were first converted into difference free energy changes using the simple thermodynamic equations below (eqs 12 and 13). Thus, with independent measurements

Figure 16.

Energetic effects of thio substitution in the ground state and transition state for DNA cleavage by vTopo and three catalytic site mutants (see text)88. Pd, phosphodiester.

| (12) |

| (13) |

of the effects of sulfur substitution on binding and the activation barrier, it was possible to dissect the overall effect on the cleavage activation barrier into ground state and transition state contributions. For example, in wild-type vTopo, Rp sulfur substitution led to an overall 3.6 kcal/mol increase in the cleavage activation barrier, which is comprised of 1.7 kcal/mol ground-state stabilization and a 1.9 kcal/mol destabilization in the transition state for cleavage (Figure 16). In contrast, the Sp sulfur substituent had little effect on the ground state binding but produced an identical 1.9 kcal/mol destabilization in the transition state. These findings suggested that the Rp sulfur anion (but not the Sp) interacts favorably in the ground state with a cluster of positively charged residues defining the active site. When the transition state conformation is reached, an additional interaction with the Sp position becomes important. These results suggested a pathway for forming the transition state that involved an initial loose organization of enzyme groups around the phosphodiester linkage in the ground state involving long-range electrostatic attraction with the Rp substituent (as indicated by the strong salt dependence of the thio effects). More extensive interactions with the phosphoryl group then ensue as the transition-state conformation is reached. A summary of the salient measurements for each mutant and their interpretation follows.

R130A(K)

Removal of Arg130 only slightly reduced the Rp thio effect in the ground state as compared to the wild-type enzyme, but essentially abolished the interaction, giving rise to the Rp and Sp thio effect in the transition state (Figure 16). An additional interesting finding with R130A is that the Rp thio effect on the cleavage activation barrier arises entirely from ground state stabilization, whereas the wild-type enzyme shows both ground state stabilization and transition state destabilization effects (Figure 16). It would appear that removal of Arg130 disrupts all of enzyme interactions with the Rp position in the transition state (including the interactions of His265 and Arg223). Such a scenario explains the especially large damaging effect of the R130A mutation. Since the R130K mutation has the same damaging effect on the cleavage rate as R130A, and in addition, produces similar nonbridging thio effects, then the Lys130 amino group must not interact with either of the nonbridging oxygens. This is a reasonable result as the shorter lysine side chain is unable to extend out far enough to make these interactions.

K167A

Removal of Lys167 reduces the binding affinity of the enzyme to the Sp and Rp sulfurs in the ground state as compared to the wild-type enzyme (Figure 16), suggesting that Lys167 directly or indirectly affects electrostatic interactions with these positions. In the transition state, removal of Lys167 resulted in a 1.5 kcal/mol increase in the transition state energy for the Sp substrate compared to the wild-type enzyme (Figure 16). This result indicates that in the absence of Lys167 a stronger interaction with the pro-Sp oxygen in the transition state exists. Since both structural and thio effect measurements indicate that Arg130 is the only residue that directly contacts the pro-Sp oxygen, then a likely scenario is that the Arg130-proSp oxygen interaction is stronger when electrostatic repulsion by the nearby Lys167 is removed. This finding provided strong evidence for thermodynamic linkage between Arg130 and Lys167 residues, as required for the proton relay mechanism proposed by Shuman and colleagues95.

R223A

Removal of Arg223 caused a decreased Rp thio effect on ground state binding and no change in the Sp thio effect relative to wild-type enzyme. The stereoselective decrease in the Rp thio effect on cleavage (relative to wild-type) indicated weaker ground state and transition state interactions with the Rp sulfur in the absence of Arg223. The results indicated that the pro-Sp oxygen did not interact with Arg223 (Figure 16).

H265A

Removal of His265 caused an 11-fold decrease in the Rp thio effect on cleavage and a 3-fold increase in the Sp thio effect102. These measurements support a favorable interaction of His265 with the pro-Rp oxygen and an indirect, anticooperative interaction with the pro-Sp oxygen.

7.2.3 Structural Interpretations

These mutational and nonbridging thio effect measurements allowed the construction of interaction maps for the nonbridging atoms in the ground-state and pentacoordinate transition state for DNA cleavage (Figure 17). The interactions shown were inferred entirely from the thio effect measurements, and are consistent with the positions of these groups in the crystal structure of the human enzyme shown in Figure 15.

Figure 17.

Ground state and transition state interactions of vTopo with the reactive phosphoryl group as deduced from thio effect and structural studies. Long range electrostatic interactions in the ground state are indicated with red hashed lines.

The nonbridging thio effect measurements also suggested a revised model for the interactions of Arg130 and Lys167 with the 5′-leaving oxygen (Figure 18). For the wild-type enzyme, Arg130 interacts with both the nonbridging and bridging oxygens: its interaction with the nascent negative charge on the 5′-leaving oxygen is likely enhanced by the presence of Lys167, which could lower the pKa of Arg130 so that it more closely matches that of the 5′-hydroxyl group. For wild-type Topo, efficient leaving group stabilization by Arg130 leads to a nonexistent 5′-sulfur rescue. For the R130A mutation, the interaction between Arg130 and Lys167 is abrogated, allowing Lys167 to move within hydrogen bonding distance of the 5′ leaving group, thereby acting as a less efficient surrogate general acid catalyst. Thus, the 5′-sulfur rescue is much greater than the wild-type enzyme, but 14-fold smaller than the maximal effect seen for the R130K mutant. In the absence of Lys167, Arg130 forms a weaker interaction with the developing negative charge on the leaving oxygen because its pKa is no longer optimally matched to the leaving group resulting in a substantial 5′-sulfur rescue (370-fold), but significantly less than the maximal value observed for R130K. For the R130K mutation (Figure 18), the Lys130 side chain is too short to reach the 5′-bridging oxygen or the nonbridging oxygens, but it is still able to interact with the Lys167 side chain, preventing its adventitious interaction with the 5′ oxygen as observed with the R130A mutation. Accordingly, the 5′ rescue is largest (2,600-fold) for R130K, and similar for the R130K:K167A double mutation (2,000-fold). Although these interpretations are not without alternatives, they are most consistent with all of the thio effect and structural data. Interestingly, a role for guanidinium groups as general-acid catalysts in phosphoryl transfer has been recently established in a model system103.

Figure 18.

Postulated interactions between Argl30, Lysl67 and the 5′-leaving oxygen based on structural studies (1EJ9) and thio effect measurements76,88.

7.2.4 Methylphosphonate Substitution and vTopo Mutagenesis

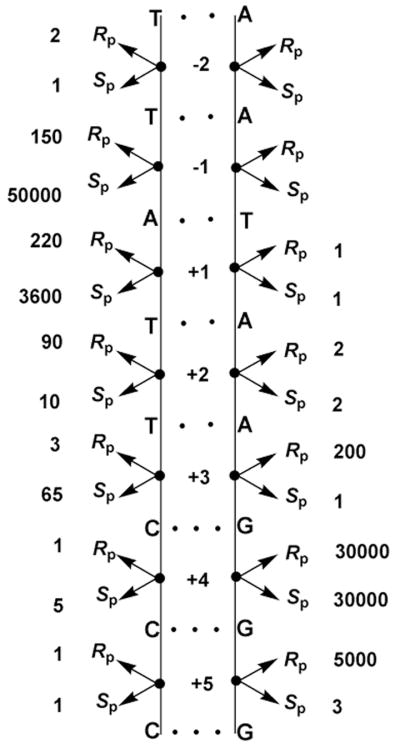

Vaccinia topoisomerase is an excellent example where methylphosphonate substitution in the DNA backbone led to useful information about enzyme mechanism104–106. Chemical substitution of the nonbridging phosphoryl oxygens by a methyl group within the consensus CCCTT sequence revealed critical vTopo-DNA contacts required for cleavage by this enzyme. Methyl substitution at eight positions within the recognition sequence had profound deleterious effects on the single-turnover cleavage rate in the range 50 to 50,000-fold (Figure 19)105. The authors divided the effects into three classes, each with distinct mechanistic interpretations. The first class involved substitutions at the +5, −2 of the scissile strand and +1 and +2 of the nonscissile strand all of which had no effect on DNA cleavage. The straightforward interpretation was that the enzyme formed no functionally significant interactions with these positions. The second class consisted of a single substitution at the +4 position of the nonscissile strand which gave rise to large deleterious effect, but with no stereoselectivity. One possible interpretation for this outcome is a long range electrostatic interaction with a cationic group (or groups), because either methylphosphonate diastereomer would equally well ablate the negative charge of the linkage. The third class involved six phosphate groups (−1, + 2, +3, +4 phosphates of the scissile strand and the +3 and +5 phosphates of the nonscissile strand) which showed large deleterious effects for only one methylphosphonate diastereomer. A reasonable interpretation for this outcome was that a stereospecific interaction with one diastereomer was occurring. However, in the absence of structural information on the complex, or additional measurements of mutagenesis effects, the details of these interactions remain unknown, although some inferences were derived from inspection of the structure of the human topoisomerase-DNA complex88,89.

Figure 19.

Damaging effects (fold) of stereospecific methylphosphonate substitution in the DNA backbone of the vTopo consensus sequence91.

Shuman and coworkers also made methylphosphonate substitutions at the scissile phosphate linkage combined these with alanine mutagenesis of active site residues Arg223 and His265106. The Sp and Rp MeP diastereomers slowed the rate of DNA cleavage by the wild-type enzyme by factors of 220 and 3600, respectively. Both the R223A and H265A mutants showed no further decrease in activity when the pro-Sp oxygen was replaced by a methyl group, but showed large rate decreases when the pro-Rp oxygen was replaced. These findings were consistent with the nonbridging thio effect measurements, where Arg223 and His265 were both found to interact with the Rp sulfur (note that the stereochemical designation is opposite for sulfur and methyl substituents; i.e. the Rp sulfur is equivalent to a Sp methyl group). Thus, methylphosphonate and thio effect studies agree remarkably well in this system.